Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Volume 57, Issue 5, P. 737-750

Volume 57, Issue 5, P. 737-750

Uploaded by

Abdul KadirOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Volume 57, Issue 5, P. 737-750

Volume 57, Issue 5, P. 737-750

Uploaded by

Abdul KadirCopyright:

Available Formats

Much has been said and written about ecology and its relation to public

health. In the following paper the author has undertaken to develop

a philosophical conceptualization of this problem, in which human

ecology is the science of man-made systems in their relation to the

biophysical environment, within which public health is a system

of principles for action, a guide to planned activity in terms

of both the individual and the community.

HUMAN ECOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH

Leo Kartman, Sc.D.

Nthe field of public health the pro- faced with a dilemma in human ecology.

I found change and flux in contempo- The answer to this and many similar

rary social relationships is reflected by questions lies in our concept of human

complex activities on a global scale ecology and public health. What follows

spearheaded by the World Health Or- may be characterized as a "position

ganization. Confronted throughout his paper" to suggest problems on a theo-

history by the devastation of infectious retical level as a basis for dialogue.

diseases man now confronts nature with

the possibility of "eradicating," or at Definitions and Beyond

least of controlling, many of these com-

municable maladies. Despite intense I have referred to public health and

nationalisms, rival socioeconomic and to human ecology, and I must confess

political systems, and the jealous pres- to a compulsion to offer definitions. Defi-

ervation of national sovereignties, the nitions are not suggested as an appeal to

nations are in accord that peace must authority but rather to generalize suffi-

prevail in the world of infection and ciently for the establishment of points of

pestilence, organic malfunction and reference and the temper of current

malignancy, and mental and emotional views. The rigidity and artificiality of

aberration. Modern industrial civiliza- definitions could not be more apparent

tion continues to exacerbate that con- than in the contemporary world of rapid

tradiction between its retrograde social transformation in all human disciplines.

relations and its sophisticated and ad- What is needed is an "extensional" (or

vanced scientific condition. In newly operational) definition that tells us what

emerged nations these conflicting cur- to do rather than what to say, that makes

rents are reflected, for example, in the us aware of things, facts, experiences,

spectacle of a declining infant mortality and the way they are related in the real

occurring simultaneously with malnu- world, rather than the manner in which

trition, starvation, and death of young they are spoken about.

children who, in the past, would never The most recent edition (1961) of

have survived childbirth. Thus man is "Webster's Third New International Dic-

MAY. 1967 737

tionary" (unabridged) has the following admonition of Gordon that, "As I speak

to say: now of medical ecology, I wish to leave

Ecology-"The totality or pattern of relations no doubt that I view the term as

between organisms and their environment." synonymous with epidemiology."3

(This is one of several definitions.) Ecology is historically and funda-

Human ecology-"A branch of sociology that

studies the relationship between a human mentally a biological science. As a dis-

community and its environments; the study tinct scientific discipline, ecology arose

of the spatial and temporal interrelationships in the latter 19th century. Yet there is

between men and their economic, social, and evidence of a Chinese calendar of 700

political organization." B. C. that recorded biological events,4

Public health-"The art and science dealing

with the protection and improvement of com- and ecological precepts were used by

munity health by organized community effort Aristotle and Theophrastus in classifi-

and including preventive medicine and sani- cations of organisms. The German biolo-

tary and social sciences." gist Ernst Haeckel usually is credited

When taken together, these defini- with first proposing the term ecology in

tions allow the development of a dy- 1869.

namic concept. We start with the totality Ecology can be divided into autecol-

of relations which, in human ecology, ogy, the study of individual organisms

embrace the man-made as well as the or individual species, and synecology,

natural environment. Public health then the study of groups of organisms. Thus

becomes a portion of human ecology synecology again can be divided into

concerned primarily with community such fields as population ecology, com-

problems of well-being. The third salient munity ecology, and ecosystem ecology.

point in the definition is the idea of In tum, these subdivisions again can be

"organized community effort" in public subdivided and it would take nothing

health. All of this seems simple and less than a separate essay to define more

clear. Study a community in depth, clearly the complexity and sophistica-

marshal all the salient facts with regard tion of contemporary ecologic thought

to the objectives of the study, and and technics. It is sufficient here to em-

finally, when all the facts are gathered, phasize that ecology is a biological

do something about it in an organized discipline.5

and planned fashion. But is it that It was inevitable that ecology as a

simple? dynamic and expanding field should be

The modern literature of public applied to man and the human commu-

health, social medicine, epidemiology, nity. Darwin can probably be given

and related fields speaks eloquently of credit for the first modern analysis in

a rather poorly defined and uncertain depth of biological and environmental

marriage of the two fields, ecology and interaction and of man's place in nature.

health.1 Some current phrases much in Nevertheless the famous essay by Mal-

evidence are: medical ecology, disease thus on population" was really an at-

ecology, medical geography, geographic tempt to formulate a general theory of

pathology, epidemiology of health, and the dynamics of human populations

medical sociology. Thus, as Audy and which, in essence, has been regarded

Wolff have suggested,2 "Epidemiologists, as a biological law, and in more recent

ecologists, and social scientists have times as part of human ecology.7

separately been developing ideas and The cognizance of human relation-

methodologies of interest to each other ships and the importance of community-

but there has been inadequate communi- environmental interaction have deep

cation between them." This confusion historic roots. It was the development

in communication is indicated in the of social medicine, with its thread reach-

738 VOL. 57, NO. 5. A.J.P.H.

HUMAN ECOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH

ing back to the Egyptian and Greco- ganisms under the purview of general

Roman civilizations, that gave much im- "ecologic laws." We can recall that Mal-

petus to the evolution of modern soci- thus conceived of man as acting like

ology.8 Today many health workers talk other organisms which tend to repro-

about the "ecology of health," and med- duce up to the limit of the means of

ical geographers hail the discovery of subsistence, inevitably ending in famine,

"disease ecology."9 In actuality con- disease, and general disaster. This has

temporary health scientists have been re- been referred to as the "ecological fal-

discovering the environment.10 An anal- lacy" or the "ecological dilemma."' The

ysis of the development of social medi- fallacy is found in the view of man as

cine indicates a long historic awareness completely enmeshed by and dependent

of these relationships. Nevertheless, upon the natural system. The dilemma

these important rediscoveries have a is found in the circumstance that man

new flavor for they come at a time when is at the same time a part of nature, and

man's view of himself is undergoing yet beyond nature.

profound change. The so-called ecologic dilemma first

A major difficulty lies in the transi- came into prominence in the pseudo-

tion from animal ecology to human ecol- Darwinian sociology of the Organicist

ogy. Park usually is given credit for school of 19th century sociology. The

the first systematic exposition of eco- biological precepts of Darwinian evolu-

logic precepts in terms of social prob- tion were mechanically applied to hu-

lems in the human community."' Work- man social relationships. These ideas,

ing with biologic principles, he antici- which are usually referred to as social

pated the now well-founded idea that Darwinism, had a great deal of influence

the human organism grows from birth and have historic roots in the United

toward self-realization in a context of States dating from the latter 19th cen-

specific relationships with and depend- tury. Even in contemporary biology we

ence on other organisms.'2 In the 17th see tendencies to revive this ecologic

century the idea of interdependence was fallacy from time to time. A leading

expressed beautifully by John Donne in contemporary biologist, in an original

his 17th "Devotion" that stated in part: and stimulating essay on the origin and

"No man is an Island, entire of itself; evolution of human culture, has said:

every man is a piece of the Continent, "I find it difficult in reading some

a part of the main . .. any man's death authors to be sure that they are not

diminishes me, because I am involved confusing biological and cultural evolu-

in Mankind. .-. ."13 Donne was far in tion-Emphasis on the animal aspect of

advance of his time as a humanist and Man, so common in current literature,

the implications of his ideas for human and a generally fatalistic attitude re-

ecology are still not fully realized today. garding human behavior may be symp-

In our time, the problem is put as toms of false concepts and applications

follows: "The attempt now is to resolve of Darwinian evolution."'51

the various ecologic concepts . . . into a In the above connection I have to

statement of ecologic laws, conceived as mention a rather curious reversal of the

extending through the life processes of ecologic fallacy exemplified by the an-

all animate things as they constitute thropomorphic view, a position adopted

groups, to include man, wild beasts, the by biologists now and then, past and

domestic animals, plants, pests and para- present, as a foundation for understand-

sites."14 This is a unifying concept yet ing animal behavior.'6 In a study of the

there is a contained danger in a whole- ecology of rodents we find this passage

sale lumping of man and other or- in a recent monographl7: "Detailed ob-

MAY. 1967 739

servation of lower forms raises doubts now must be extended to space bio-

as to the frequently implied absence of technology and the field of extrater-

symbolic communication, attitudes, and restrial exploration and life.

value systems in forms other than man. To the sociologist, ecology represents

For example, there is the ethic of honor one of the disciplines that has been taken

your father and mother. Operationally, from the natural sciences and applied

rats exhibit behaviors indicating con- to the study of human society.18 The

formance to such a tenet." This is the equilibrium attained by the human popu-

ghost of social Darwinism standing on lation in a given region is referred to

its head. By the logic of this sort of as the "web of life." Man and his

comparative examination of social be- cultural institutions are considered as a

havior (the author's title in part is part of this web in which a purposeful

- . Sociology of the Norway Rat") evolution is superimposed on (or sub-

not only can rat behavior be shown to stituted for) the objective processes of

contain within itself an expression of the natural world. To many sociologists

human ethical behavior but, carried to all of these interrelations are manifesta-

its logical end, I have no doubt that the tions of a basic ecologic process, competi-

basis of human emotion, competition, tion, which in its "pure" form is an im-

war, love, status seeking, and so forth personal striving for advantage. How-

can be equated with the "value systems" ever, when men become aware of their

underlying the psychosociology of the antagonists they try to eliminate them

Norway rat and perhaps even the house with the result that open, intense rivalry

mouse. I trust that this tendency toward and conflict occur. Sociologists have de-

a unification of animal and human ecol- veloped several schools of thought in hu-

ogy does not become accepted generally man ecology ranging from the direct ap-

since it would place fetters upon the plication of the principles of biologic

study of human ecology and restrict ecology to a humanistic, society-oriented

meaningful investigation for some time. discipline. This is a subject of immense

It seems important to differentiate proportions and cannot be discussed

between the application of ecologic here, but one should point out that it is

principles and methods to the study and the sociologists and social anthropolo-

solution of biological or biotechnical gists who have been largely responsible

problems-on the one hand, and their use for developing and enriching the field of

in the study of man himself on the other. human ecology.

Ecologic methods are being used, for The ecological view of humanity ap-

instance, in the vital field of the con- pears to have attracted sociologists, an-

servation of natural resources. Ecolo- thropologists, geographers, and biologists

gists contribute valuable observations to a common ground. More recently,

and experimentation in problems con- public health and medical scientists seem

nected with wildlife management, for- to have joined these ranks in force.

estry, agriculture, pesticide residues, Within the past decade public health

stream pollution, fisheries, range man- workers have adumbrated human ecol-

agement, and so on. A younger field is ogy in relatively simple terms. One

that of radiation ecology in which prob- authority sees human ecology as the

lems of radioactive fallout, waste dis- "study of the relations between man

posal, and the fate of radioactive iso- and his environment, both as it affects

topes in different environments are him and as he affects it."7 Another

studied. Here also would be placed the says that human ecology is the "study of

application of ecology to the natural his- the mutual relations of man and his or-

tory of disease. In addition, the concept ganic and inorganic environment, his

740 VOL. 57. NO. S. A.J.P.H.

HUMAN ECOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH

adaptations, his struggle for existence, leading problems are approached on

his parasites, and the like."19 During an both national and local levels. And this

earlier period, about World War I and fragmentation is reflected in the organi-

the following decade, a number of social zational framework of health agencies

scienlists advanced the thesis that geog- and their practice of attacking problems

raphy is the science of human ecology. item by item.

The main concern was the way in which

physical factors influence human civili- The Individual and the Community

zation. Human geography was in-

terpreted as the ecological study of so- The increasing complexity of urban

ciety. The repercussions of these ideas and suburban population dynamics, the

are seen in our own day in the equat- tendency of industry to become more

ing of medical geography with what is highly technical, the introduction of

called "disease ecology."9 new man-made hazards such as ionizing

The above views are but very few radiation, and the concomitant increase

examples of definitions. It is fairly clear in the incidence and diagnosis of mental

that the term "human ecology" implies and emotional illness are reflected in the

the broadest possible view of human more diversified and complex nature of

beings, both as individuals and as popu- community health problems. Whereas in

lations, in terms of the ecosystem, that the past mass disease was closely asso-

is, the biologic, socioeconomic, political, ciated with a natural origin connected

cultural, and emotional complexes in primarily with the external environment,

their dynamic action and reaction. What- the mass diseases of today, in a Western

ever man does, what he thinks, how society like the United States, are pre-

one man reacts to another man or to a dominantly social in origin and are more

circumstance either natural or man- integrated with characteristics of the hu-

made, how a human group functions man host and his socioeconomic environ-

within itself and reacts to other groups ment. The chronic maladies and the be-

and to situations, how each thought, havioral disorders seem less amenable to

emotion, habit, aberration is translated community-oriented control than are the

into human activity, and how human infectious diseases. Thus some authori-

creativity arises, matures, or is repressed ties suggest that modern public health

-all of these and thousands of other practice must envisage a change in

complex processes are of the warp and method even though the general princi-

woof of human ecology. "The entire ples guiding the control of community

history of human civilization and tech- health problems remain essentially the

nology is a history of human ecology in same. This change consists of greater

so far as it concerns changed relations emphasis upon the cooperation and in-

towards nature, its domination and ex- terest of the individual since in many

ploitation."20 One of the main concerns situations the individual no longer can

of human ecology today would seem to depend upon the community for protec-

be a focusing of attention to the essen- tion and prevention.21 It is argued that

tial holism of human problems. This the field of public health education now

overlapping and interpenetration has has greater significance since the "new"

been recognized for a long time and public health is one in which there is

many have pointed to the artificiality of "a common effort by epidemiologist and

fragmenting and compartmentalizing re- educator through the principles of hu-

lated areas of investigation and practical man ecology."22

activity. The evidence still is all around There can be little doubt that the pre-

us in the piecemeal manner in which cept of individual responsibility seems

MAY, 1967 741

germane to the framework of a develop- recovery. Yet at present it must be

ing complex industrial society of es- recognized that with a problem such as

sentially democratic content. Such a view cancer the multifactorial causes remain

appears consistent with the idea that in a relatively obscure. Intelligent action still

democracy the education of the indi- must wait for a much greater under-

vidual is of basic importance and that standing of its ecology in man and such

the ultimate result of education is the an understanding primarily is a product

emergence of the mature, responsible in- of collective research followed by mass

dividual who is responsive to his own propaganda, all of which is directly de-

needs in the sense that self awareness pendent upon the amount of money that

leads to social health. Nevertheless, I a given society is willing to spend for

am convinced that the practical con- investigation. Even when a reasonable

cern now, and for a considerable period cause-effect relationship has been demon-

in the future, is community health and strated, as with the carcinogenic role

environmental health. Even though many of tobacco, man-made obstacles as busi-

theorists in public health speak of infec- ness interests appear to raise barriers

tious disease almost in terms of histor- that frustrate the individual in his

ical curiosities, the facts show that such search for personal freedom from dis-

illness as streptococcal infections, tuber- ease. The helplessness of the individual

culosis, salmonellosis, venereal disease, in situations of this kind emphasizes the

and other communicable diseases still contradiction between enlightenment on

remain serious threats to well-being the one hand, and the frustration of

even in the most advanced countries. intelligence by the very sociocultural

The viral infections, although of long forces advocating and furthering that

standing, still are part of an expanding enlightenment. This is an example of a

medical universe and it has been sug- significant problem in the human ecol-

gested that we are now entering the ogy of public health.

antiviral era just as the 1930's ushered The hospital, like social institutions in

in the age of antibacterials. general, tends to maintain a status quo

It is true, of course, that the develop- in its attitudes and practices. Neverthe-

ment of mass immunization and anti- less a tendency toward change is dis-

biotic therapy and prophylaxis has, to cernible, determined in large measure

a large extent, controlled the so-called by nontechnical factors. The most out-

crowd diseases. Yet a leading authority standing change is in the area of the

in this field has suggested that the cur- individual patient's attitude toward his

rent situation represents a kind of truce illness so that the patient's feelings about

within which many bacterial diseases self, about his doctor, and about the

are suppressed while their etiologic hospital have become factors in the na-

agents continue to exist and to propagate ture of his treatment. Whereas in the

in the natural environment. This truce past a "humanitarian" motive dictated

may collapse at any time, as, for in- that the patient be made comfortable,

stance, the sudden and tragic increase of the current view assumes that psycho-

staphylococcal infections in hospitals.23 social factors are of primary concern.

In the area of malignant disease the The patient now is to be given what is

enlightened individual has the advantage called "comprehensive care" in which

of being motivated toward periodic his identity with the world outside the

checks upon his health, and if already hospital is maintained.24

sick he will more readily seek and follow The consequences of the trend have

the indicated medical or surgical prac- implications for both the patient and the

tice that offers a maximum chance for physician. From the ecological stand-

742 VOL. 57. NO. 5. A.J.P.H.

HUMAN ECOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH

point, the patient can begin to deal with burden."27 I have strong doubts that

the "total" reality of his existence, with epidemiology can be separated from

the full implication of his consciousness morality, but that is a problem needing

in terms of an active interest in creat- exposition elsewhere.

ing conditions in which his illness will If every physician actually would

be terminated. More than that, this in- notify the health authorities this would

dividualization begins to square with the mark a tremendous advance in view of

new reality of a longer life span, i.e., the the fact that a survey in 1963 showed

responsibility and necessity of coping that for every privately treated case of

with the problems of life rather than infectious syphilis identified and re-

with illness and death. The problems ported, approximately nine cases had

of health have become paramount. "We been identified, treated, and not re-

are faced with the fact that perhaps ported. Only a little more than 10 per

one-half of all patients or more have cent of cases of infectious syphilis

nothing wrong with them in terms of treated by private physicians are being

prospective death. Can we say that there reported. In 1962, while about 20,000

is nothing wrong with them in terms of cases were reported by clinics and phy-

prospective life ?"25 sicians, closer to 100,000 more were

To the physician, the changing atti- diagnosed and treated.28

tude of the patient helps to pave the The collaboration of the private physi-

way for an acceptance of the practice of cian with the public health epidemi-

clinical epidemiology in the broad eco- ologist should tend to stimulate in the

logic sense.26 In a field such as venereal medical practitioner an ecologic, or soci-

disease, where the attitudes of both the ologic outlook that has become a neces-

patient and his physician are of critical sity in the contemporary world of sharp

significance to programs of control and social change. It seems a bit sad that

prophylaxis, these tendencies to greater public health workers must deal with

involvement must in the long run create the politics of expediency. The neglect

the conditions for increasing social re- of epidemiology still is based, to a large

sponsibility. A public health expert has extent, upon that figment of individual-

stated that the "pivot in an eradica- istic imagination-the privileged and

tion program" for venereal disease "is sacred physician-patient relationship. In

the doctor in private practice." The the context of a serious communicable

practitioner must cooperate with public disease, specifically social in nature,

health authorities in locating sexual such a view is primitive indeed. Yet in

contact so that the complete epidemi- the United States the anachronism of

ology of each case can be revealed. How- individualism persisting from the fron-

ever, this same authority feels that "it is tier past into the present world of so-

not realistic to ask or expect the aver- cially-oriented democratic public health

age physician today to spare the extra practice continues to fetter the private

hour or often more of time required for physician who has yet to take the critical

a thorough probe for contacts. ... step of practicing clinical epidemiology

Thus the ideal system is "for the physi- with emotional freedom and with a sense

cian to diagnose and treat, and then of responsible personal choice. When

call the public health epidemiologist ... the physician has at last ceased to focus

and request him to interview the pa- his exclusive attention on the patient's

tient as soon as possible." In this rela- complaint, per se, he will assume the re-

tionship the private physician is spared sponsibility for involvement in the eco-

the "active burden of epidemiology" logic realities of the world surrounding

. . . but . . . "he must bear the moral a particular patient, i.e., a concern for

MAY, 1967 743

the totality of welfare of his patient. The paper presented by that eminent his-

result can be only in the direction of torian of public health, Rosen, who paid

socially responsible activity wherein the close attention not only to the social en-

needs of the individual and of the com- vironment and the social context of

munity are recognized and are merged. these problems, but pointed out the

necessity for planned changes in the so-

Knowledge and Action cial environment as a prerequisite for

the solution of these problems. Rosen's

Knowledge implies the necessity for paper is important because it goes be-

action. Concern, when based upon yond the mere observation of ecologic

knowledge, is an empty emotion unless relationships and tackles the more im-

it becomes part of action. The test of portant area of human action and hu-

how well we have understood the prob- man decision to change these relation-

lems of public health in their wider so- ships.10

cial context is the test of the degree of One of the primary consequences of

our concern to chart a course of action scientific knowledge, it would appear, is

and to maintain control over it. Tolstoy the launching of practical action to pre-

once wrote a short story entitled "God vent a particular concatenation of events

Sees the Truth But Waits." In the field that is recognized as a threat to a com-

of human ecology and public health munity. It seems a sad truism that

many significant "truths" have been catastrophes have occurred over many

grasped, but practical activity by a so- decades and communities continue to

cially responsible force quite often is "do business as usual" as though the po-

completely lacking. Silence never was tential for repetition is nonexistent. To

a hidden truth, it has been the mark floods, cyclones, and earthquakes may

either of a deadening conformism or be added epidemics due to biologic

of the deliberate attempt to prevent ac- pathogens as well as to man-made toxic

tion and innovation. agents and stresses such as social con-

If we can develop a humanist eco- flict and international war.

logic view in public health, then we can Admittedly, man cannot control na-

begin to approach man as a totality ture to the extent that its most awesome

without prejudice and with the candor disturbances are prevented. Neverthe-

needed by true "generalists" as practic- less, if man takes his own ecology seri-

ing scientists-educators. Without some ously, he must begin to modify his way

guiding principle the discussion of hu- of living in relation to his knowledge

man ecology and health bogs down into that certain events are cyclic and that

a recital of special problems. Thus a others will recur from time to time. In

recent conference held at the New York short, human ecology must abandon its

Academy of Medicine focused attention childhood, a state in which history has

on the biological, physical, and chemical little or no meaning. To the scientist

factors of the environment in relation to history is not only a record of past

human health, with emphasis on such events and past ideas, it is also in vary-

topics as pesticides, ionizing radiation, ing degree a basis for the prediction

and pollution. Experts and specialists of future events.

discussed these topics brilliantly, but In my own field of public health I

these matters have been talked about ad have noted the activity of highly skilled

infinitum in recent years. Nowhere in scientists and team of specialists on both

these talks was there a realistic recog- foreign and domestic assignments who,

nition of the broader concepts and the over the years, have investigated all

larger problems involved, except in the sorts of epizootics and epidemics and

744 VOL. 57. NO. 5. A.J.P.H.

HUMAN ECOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH

have conducted exhaustive surveys. They the critical importance of politics as an

have revealed and recorded an amazing ecologic factor in the practice of public

variety of infectious agents and their health.

epidemiologic complexities, and they The struggle against poverty, as a

have written hundreds of reports and major program of human ecology, should

have published other hundreds of be examined carefully by every worker

learned papers. The knowledge gained in the fields of public health and medi-

has been amazing. Yet, for various cine. A close examination will reveal

reasons, it has been difficult in many that the ecology of human disease must

cases to put the knowledge to work, to start with the social fabric and once

initiate and carry out anticipatory ac- that becomes clearly defined the matters

tion, of action before the fact, of pro- of public health can be delineated and

phylactic action as a major program in analyzed in terms of their interrelation-

public health. ships in that social fabric. The starting

In a context of human ecology the point is not a disease or the prevalence

basis of public health resides in the use of infection, and it is not epidemiology,

of specialized knowledge for the manipu- it is the social unit. A study in "disease

lation of community forces. Thus, it ecology" begins with the socioeconomic

is necessary that specialists work to- and behavioral status of a population,

gether with social and political agencies defines that status in terms of the total

in the practical tasks facing communi- ecologic picture, and then proceeds to

ties so that the attack upon health prob- the study of health problems that are

lems becomes part of a program of so- recognized as an organic part of the

cial planning. If slums are cleared in a totality of human relationships involved.

metropolis, to be replaced by good hous- The outcome of such a study would be

ing, clean streets, and a general elimina- to define health in terms of the social,

tion of important environmental stres- economic, and political realities in a

sors, the real benefits must accrue to the given community. This is the type of

former residents of these slums if the knowledge that provides a basis for in-

original problems are not to be per- telligent, democratic action.

petuated and even exacerbated. There The specialist may not recognize or

are too many examples of failures and consider that human ecology implies re-

in these circumstances crowd diseases sponsibility. This is not surprising in a

are moved from one area to another culture where few scientists are con-

along with the social conditions that fa- cerned with the social implications of

vor their endemicity. During an early their work. The comfort of specializa-

historic period the ecologic key to such tion dies hard, but there are occasions

conditions was primarily economic since when the social apathy engendered by

a certain level of unemployment was ac- specialization is shaken from its roots.

cepted as being necessary for the mainte- I recall a parasitologist friend who, after

nance of profit through presssure on having earned his doctorate with a neat

the labor market. Today, poverty and dissertation on a tidy little experimental

unemployment are officially looked upon project, went to India and plunged into

as evils, as social diseases, and by po- the parasitologic problems of workers in

litical legislation a nationwide program a jute mill. He was overwhelmed by

has been developed to eliminate them. the mass nature of parasitic problems

Thus the current ecologic key is not so under Indian conditions as contrasted

much a matter of economics as it is of with the innocuous status of the same

politics. The complex hearings before parasites in the United States. He spoke

congressional committees bear witness to about the pressing need to control these

MAY, 1967 745

parasites, some of which were virtual demiologian renders his unique and vital

curiosities at home and were being contribution to the solution of social

maintained in the laboratory for use problems."

in fascinating experiments the results of The modern public health worker en-

which could be used to pad bibli- gaged in research has encountered this

ographies. I have had a similar ex- dilemma many times: Should investi-

perience. gation be arbitrarily halted or given

How many times has someone stated, less emphasis at a certain stage and ma-

"We don't know enough about the fac- jor energies be devoted to control activi-

tors, the ecologic conditions that favor ties? It is my contention that the human

these infections. We need more re- ecologist in public health must be con-

search, more surveys, more investiga- scious of the necessity for this choice

tions before we can go in and control, and that when the moment arrives he

let alone attempt to prevent." The road must choose in favor of the "greatest

to limbo is beautifully paved with sur- good for the greatest number." Oliver

veys and sophisticated experimental in- Wendell Holmes put the matter pre-

vestigations. There is no end to the study cisely: "We need education in the obvi-

of basic epidemiologic mechanisms. Yet ous more than in investigation of the

I venture to assert that in spite of a obscure."29

lack of complete knowledge in an area We do not need more scientists in

such as bilharziasis in Puerto Rico, for public health, but more men and women

example, the means are at hand to re- of understanding who do not fear the

duce the problem to insignificance pro- ecologic implications of their science. We

vided sufficient funds could be obtained. need fewer compilers of data and more

Even more obvious is the circumstance specialists who think in creative gen-

that the rash of encephalitis epidemics eralities. The existing data pile has

in certain areas of the United States reached a mass that already extends be-

during 1964 could have been prevented yond our use of it. The data pile does

by mosquito control programs ade- not insure progress automatically; it

quately financed and conscientiously does not give assurance that some uni-

applied. versal good or some great utility shall

Of interest here is a statement made arise to rescue humanity from its ills.

in the "News Letter" of the American The gathering of data often is a serving

Public Health Association, Epidemiology of what has been referred to as the cult

Section, page 7, March, 1965, which of newness. Thus in practice this serv-

follows in part: ". . . today many po- ing of the data pile becomes a process

tential leaders in the field of public of rejection and this amounts to a nega-

health who have observed the gathering tion of creativity, since that which is re-

of massive evidence concerning the dele- jected quite often has not been under-

terious effects of tobacco on health- have stood or evaluated. Knowledge is re-

failed to act upon such evidence be- jected or conveniently forgotten be-

cause it is not yet perfectly complete. cause the continual seeking for "new-

Their inaction is perhaps especially a ness" has become a -way of life sub-

product of the unfortunate concept, still servient to the insecurity of the indi-

prevalent among epidemiologists, that vidual scientist operating in a world

absolute or perfect proof of causality is a where dispensers of funds demand new-

possible and necessary basis for preven- ness as the basic condition for their

tive public health action . . . it is by generous grants. The ecologic implica-

forthright exercise of . . . judgment of tion of this unconscious rejection of

the whole, undismayed by obstructive knowledge is the frustration of purpose-

'thread-picking' arguments, that the Epi- ful action.

746 VOL. 57. NO. 5. A.J.P.H.

HUMAN ECOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH

It is sometimes the case that the wonder how many remember and how

stimulus for changed views and for ac- many have weighed the implications of

tion comes from a source outside the that message ?

framework of a given field. Thus the

controversial book "Silent Spring" was A View of Human Ecology and

a catalyst to action by toxicologists and Public Health

by pesticide specialists who were merely

acting on the basis of information that The concept of human ecology and

had accumulated for many years and public health suggests a consideration

about which they were acutely aware. of the unity of theory and practice as

The sessions of the Seventh Interna- the main concern of man as a social

tional Congresses of Tropical Medicine being. The dynamic union of thought

and Malaria, held in Brazil in 1963, and its application may be viewed as a

were impressive in their presentation of series of steps in a process of social

a wealth of knowledge. Even the most reproduction. More than that, the very

casual observer could conclude that recognition of public health in a wider

enough is known about many of the context of human ecology is simultane-

most devastating tropical maladies to ously a cognizance of the necessity for

reduce their incidence significantly and transforming the human condition, of

to fundamentally alter their effects. Yet, consciously planning and manipulating

with the possible exception of the field ways and means to so modify the bio-

of malariology, there seems to have been social environment that forces are cre-

demonstrated an ever-widening chasm ated that will in turn fundamentally

between ecologic knowledge and the change the problems of public health.

necessary activity to use that knowledge. The active nature of human ecology

In a message to the Congresses the then will become recognized because it op-

President of Brazil, Joao Goulart, re- poses a spirit of humanism and personal

minded the members that their responsi- engagement against the objectivity and

bility was concerned with matters far essentially passive nature of ecologic

more profound than the research to dis- thought exemplified by the field of ani-

cover the natural mechanisms operating mal ecology. Man can observe the ecol-

in tropical diseases. He reminded them ogy of animals, experiment with it, ex-

of the danger of their abdication from plain it, and modify it when the knowl-

the responsibilities of human ecology in ledge and means are at hand. In this

the following words: activity man observes, describes, and

"I want to take this opportunity to remind manipulates a world outside himself. In

those present, particularly the representatives human ecology the fundamental and im-

of Latin America, African and Asiatic peoples mutable difference is that man deals

who, as much as the Brazilians, still live under actively not only with the product of his

the burden of pauperism, that so-called tropical consciousness, culture, but also with the

diseases are much more the fruit of our un-

derdevelopment than the result of the generous, very nature of that consciousness, its

though often slandered, climate of our coun- epistemology, its subconscious motiva-

tries. Your efforts . . . must not obscure the tions, and its morality.

fact that only a profound change in the social In public health, as in all science, the

and economic structures of our countries will

be able to solve the distressing problem of our idea of amorality is a myth. This is a

people's health."30 lesson of human ecology. If this could

not be recognized in the past, the ques-

It is now three years after those words tion has been settled forever since

were spoken to many of the world's Hiroshima and Nagasaki. What more

leading figures in tropical medicine. I profound problem in public health could

MAY, 1967 747

man have visited upon himself than in The above formulations imply nothing

the intensification and exacerbation of more nor less than the real objective of

the technical means underlying that su- public health, the goal of preventing

preme problem of human health-war? destructive maladjustments to the bio-

It has become impossible for science physical and the man-made environ-

to claim objectivity in human matters. ment. In this morality human ecology

Human ecology and public health can- and public health interpenetrate and are

not be either objective or amoral but transformed to function as any scientific

must accept the concept of change as a discipline, that is, to extend and deepen

sacred morality. The consequences of practice by increasing its effectiveness

this view are not only the acceptance of, in terms of its own peculiar struggle with

but the built-in need for, directed the forces of nature and with the process

change as an organic factor in the of social development that has been

"system." Applying this temper to the superimposed upon nature. Setting aside

field of human disease, I suggest that the impact of individual problems, of

the practice of public health must segments of theory, of separate princi-

square with the precept in science that ples, of isolated examples of practice,

creative research holds within itself the I want to emphasize that we are dealing

future obsolescence of the products of basically with systems as a totality, of

its own creativity. Max Weber has put practical action appropriate to that to-

it this way: "Every scientific 'fulfill- tality, representing an unending, un-

ment' raises new 'questions'; it asks compromising, and self-conscious con-

to be surpassed and outdated."3' frontation with the biologic, sociologic,

Sociology and anthropology are en- and psychologic complexities of human

gaged in the study of man, his cultures, life. This can be a most fruitful concept

and his societies as they exist and as for human ecology and public health, a

they have existed in history and pre- view that begins with the uniqueness of

history. The idea of human ecology, on man and his purposeful social Lamarck-

the other hand, is only a semantic sub- ism as distinguished from the Darwinian

stitute for sociology and anthropology ecology of nonhuman life.2

unless it brings some new and significant Those who advocate the view that

element into man's search for an under- human freedom has a biological basis

standing of himself. This element, as present persuasive arguments in its fa-

I have already suggested above, is the vor.33 If this precept be correct, I would

conception of human ecology as action- suggest that the next step in evolution

oriented. This implies the difference be- will result from man's self-conscious

tween a study of "what is" or "what has activity striving for a human basis of

been" and an examination of "what can freedom from biology. Whether or not

be." More than that, due to the totality of such a goal is attainable is of small conse-

its view, human ecology becomes an ac- quence. The importance of the idea is

tivity of man to transform the idea of that in the course of struggle toward

"what can be" into the reality of a quali- such a vision man will transform both

tatively new "what is." Thus human the material world and himself in the

ecology becomes the theory and practice process. History already demonstrates

of sociologic and anthropologic engineer- impressive evidence for these trans-

ing. It becomes the self-cognizance of formations. The essence of the idea is

the social sciences, their conscience, and illustrated in the remarks of Dr. Al-

their ethos. To all areas of human bert Starr commenting on the highly

thought it brings the necessity for ac- successful Edwards-Starr artificial heart

tion as a consequence of ecologic con- valve now being used by surgeons in

sciousness. many countries. He said: "Our job is

748 VOL. 57, NO. 5, A.J.P.H.

HUMAN ECOLOGY AND PUBLIC HEALTH

not to design a valve identical to na- those factors of dis-ease that tend to in-

ture's, not to see how close we can hibit the intelligent, conscious, and pur-

come to duplicating a natural phe- poseful struggle of humanity toward a

nomenon, but to overcome the clinical state of personal and social freedom.

problem of the diseased heart valve."34

In the future, I believe that the na- REFERENCES

ture of the transformation will be one 1. Bates, M. In: Medicine and Anthropology. I. Gald-

of greater humanity, of a human ecol- ston (ed.). New York, N. Y.: International Univer-

sities Press, 1959, p. 56.

ogy that finally becomes irrevocably 2. Audy, J. R., and Wolff, R. J. In: Symposium,

divorced from animal ecology. In that Division of Public Health and Medical Sciences,

Tenth Pacific Science Congress, Honolulu, 1961,

sort of milieu the design and practice 6 pp. mimeo.

of public health will be characterized 3. Gordon, J. E. In: Proceedings of the Conference on

Genetic Polymorphisms and Geographic Variations

by a humanistic planning for the eradi- in Disease. B. S. Blumberg (ed.). Washington, D. C.:

cation of health problems and the transi- Gov. Ptg. Office, 1960, p. 67.

4. Brewer, R. Occasional Papers. C. C. Adams Center for

tion to an almost exclusive preoccupa- Ecologic Studies, No. 1, 1960.

5. Odum, E. P. Fundamentals of Ecology. (2nd ed.).

tion with the problems of conscious- Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders, 1959.

ness, of unexpressed reality, of mental 6. Malthus, T. R. An Essay on Population. New York:

Dutton, Everyman's Library (2 vols.), 1914, first

and emotional health in terms of both published in 1798.

the individual and the community. In 7. Rogers, E. S. Human Ecology and Health. New York:

Macmillan, 1960.

this context, as Julian Huxley put it, "the 8. Rosen, G. In: Handbook of Medical Sociology. H.

highest and most sacred duty of man E. Freeman; S. Levine; and L. G. Reeder (eds.).

New York: Prentice Hall, 1963, p. 17.

is seen as the proper utilization of the 9. May, J. M. The Ecology of Human Disease. New

untapped resources of human beings."35 York: MD Publications, 1958. J. M. May (ed.).

Studies in Disease Ecology. New York: Hafner, 1961.

This I consider to be a prime objective 10. Rosen, G. Human Health, Community Life, and the

Rediscovery of the Environment. A.J.P.H. 54:1

of human ecology and public health. (Suppl.), 1964.

Human ecology is the science of con- 11. Park, R. E. Am. J. Soc. 42,1, 1915.

12. Montagu, A. On Being Human. New York: Henry

ceptualizing biological systems (human Schuman, 1950.

beings) operating primarily within an 13. Untermeyer, L. The Concise Treasury of Great

Poems (Permabooks Edition). New York: Doubleday,

extra-biological world of their own crea- 1958, p. 98.

tion (society, culture, historical aware- 14. Gordon, J. E. Am. J. M. Sc. 235:337, 1958.

15. The arguments of the Organicists can be found in

ness). Thus human ecology is the sci- Gumplowicz, L. The Outlines of Sociology. Tr. by

F. W. Moore. Philadelphia: American Academy of

ence of man-made systems, their herita- Political and Social Science, 1899. See also the

bility and mutability, and their relation following: Blum, H. F. Am. Scientist 51:32, 1963;

Hofstadter, R. Social Darwinism in American

to the biophysical environment. Human Thought, 1860-1915. Philadelphia: University of Penn-

ecology is partly biology and in part sylvania Press, 1945; Kartman, L. Sc. Monthly 62:

337, 1948; Kartman, L. Am. Scientist 44:296, 1956.

sociology and anthropology. But beyond 16. Katz, D. Animals and Men: Studies in Comparative

these, it has its own peculiar jurisdic- Psychology. London: Penguin Books, 1953.

17. Calhoun, J. B. The Ecology and Sociology of the

tion, its own unique character. This is Norway Rat. PHS Publ. No. 1008. Washington, D. C.:

Gov. Ptg. Office, 1963.

its transcendent nature which projects 18. Groves, E. R., and Moore, H. E. An Introduction

it beyond the biologic and cultural en- to Sociology. New 'York: Longmans, Green, 1940,

pp. 47-64.

vironments and, while including these 19. Francis, T., Jr. Am. J. M. Sc. 237:677, 1959.

factors, it functions on a higher action- 20. Bodenheimer, F. S. Animal Ecology To-Day. Dr.

W. Junk, The Hague, Netherlands, 1958, p. 237.

oriented level with the conscious pur- 21. Martin, W. J. M. Officer 104:273, 1960.

pose of changing the human condition 22. Gordon, J. E. Changing Accents in Community

Disease. A.J.P.H. 53:141, 1963.

toward desirable goals. Thus ultimately, 23. Koprowski, H. In: Man and His Future. G. Wol-

stenholme (ed.). Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown, 1963,

human ecology is the theory and prac- p. 196.

tice of human freedom. Within this 24. Bloom, S. W. The Doctor and His Patient. New

York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1963, p. 157.

purview, I see public health as a system 25. From an unpublished address in 1954 by I. Starr to

of principles for action, a guide to first year medical students in a study of the soci-

ology of medical education, Columbia University.

planned activity that seeks to negate Qiioted by Bloom, 24 pp. 157-158.

MAY, 1967 749

26. Paul, J. R. Clinical Epidemiology. Chicago, Ill.: ology. H. H. Gerth and C. W. Mills (eds.). New

University of Chicago Press, 1958. York: Oxford University Press, 1946, p. 129.

27. Brown, W. J. In: Syphilis and Other Venereal Dis- 32. TIhis distinction between Lamarckian and Darwinian

eases. J. B. Youmans (ed.). Med. Clin. N. America evolution has been pointed out by P. B. Medawar

48,3:573-581, 1964. (The Future of Man, Basic Books, New York, 1960,

28. Fleming, W. L. Ibid., pp. 587-612. pp. 98-99) who suggests that social evolution is

Lamarckian in the sense that the social environment

29. Quoted by Adlai E. Stevenson in an address at the imprints "non-genetical information which we can

Annual Banquet of Planned Parenthood-World Popu- and do pass on."

lation, New York City (Oct.), 1963. See The Popu- 33. Dobzhansky, T. The Biological Basis of Human

lation Crisis and the Use of World Resources. S. Freedom. New York: Columbia University Press,

Mudd (ed.), Vol. 2, World Acad. of Art and Sc. 1956; Gerard, R. W. Philos. Science 9:92, 1942;

(Dr. W. Junk, The Hague, Netherlands, 1964) p. Dubos, R. Am. Scientist 53:4, 1965.

xiii. 34. From an interview reported in Today's Health (Jan.),

30. Anonymous. J. Trop. Med. & Hyg. 66:269, 1963. 1964, pp. 52-53.

31. Weber, M. In: From Max Weber: Essays in Soci. 35. Huxley, J. Quoted by Dobzhansky, ibid.

Dr. Kartman is scientist director, Communicable Disease Center, PHS,

Technology Branch (San Francisco Field Station, 15th and Lake St., Bldg. 18),

San Francisco, Calif. 94118.

This paper was submitted for publication in August, 1966.

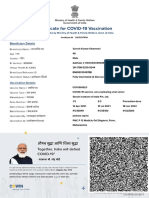

Cigarette Contents

Following is a table giving the average tar and nicotine per cigarette in

milligrams:

Tar Nicotine Tar Nicotine

Brand Type* (mg) (mg) Branid Type* (mg) (mg)

Marvel KF 8.3 0.32 Chesterfield R 27.0 1.18

Cascade KMF 9.1 0.34 Lucky Strike R 27.1 1.42

Carlton KF 9.7 0.74 Oasis KMF 27.1 1.38

King Sano KFD 12.0 0.39 Lucky Strike KF 27.3 1.42

Duke KF 12.3 0.46 Chesterfield KF 27.6 1.72

Life KF 13.6 0.97 Raleigh KF 27.8 1.98

True KF 15.8 0.80 Philip Morris R 28.8 1.37

Kent KF 18.8 1.10 Belair KMF 29.7 2.11

Montclair KMF 21.1 1.15 Old Gold R 29.7 1.63

Spring KMF 21.7 1.16 du Maurier KF 30.0 1.96

Galaxy KF 22.1 1.43 Players R 31.0 1.67

Marlboro KF 22.4 1.24 Camels R 31.3 1.69

Winston KF 22.9 1.32 Camels KF 32.4 1.77

Old Gold KF 23.0 1.32 York K 32.4 1.69

Waterford KF 23.0 1.40 Pall Mall K 33.0 1.75

Lark KF 23.1 1.26 Half & Half KF 33.6 1.99

Philip Morris KF 23.2 1.46 Domino K 34.1 1.48

Newport KMF 23.3 1.34 Old Gold K 34.8 1.89

Viceroy KF 23.4 1.68 Masterpiece KF 35.9 2.23

Salem KMF 23.6 1.43 Kool RM 36.3 2.21

Paxton KMF 23.8 1.43 Fatima K 36.7 1.73

Parliament KF 24.0 1.44 Philip Morris K 37.2 2.11

L&M RF 24.9 1.12 Brandon K 38.5 2.35

Benson & Hedges RF 25.0 1.55 Benson & Hedges 100 KF 39.3 2.29

Tempo KF 25.1 1.68 Holiday K 41.1 2.45

Tareyton KF 25.3 1.35 Tareyton K 41.5 1.97

Alpine KMF 26.4 1.52 Pall Mall KF 41.6 2.20

Kool KMF 26.6 1.88 Raleigh K 43.4 2.64

*

K-king (80-100 mm), R-regular (70 mm); F-filter, M-menthol, D-denicotinized.

(This is the material referred to in the editorial which appears on page 730 of this Journal.

The list was published in the New York Times, March 15, 1967.)

750 VOL. 57, NO. 5. A.J.P.H.

You might also like

- Human Ecology in Medicine: Johk Bhuiin' SchoozDocument17 pagesHuman Ecology in Medicine: Johk Bhuiin' SchoozTere CCamacho de OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Structural Human Ecology: New Essays in Risk, Energy, and SustainabilityFrom EverandStructural Human Ecology: New Essays in Risk, Energy, and SustainabilityNo ratings yet

- The Social Direction of Evolution: An Outline of the Science of EugenicsFrom EverandThe Social Direction of Evolution: An Outline of the Science of EugenicsNo ratings yet

- The New Ecology: Rethinking a Science for the AnthropoceneFrom EverandThe New Ecology: Rethinking a Science for the AnthropoceneNo ratings yet

- Human Ecology: Human Ecology Is An Interdisciplinary and Study of The Relationship Between Humans andDocument4 pagesHuman Ecology: Human Ecology Is An Interdisciplinary and Study of The Relationship Between Humans andUsman SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Book Reviews: Humanity and Nature: Ecology, Science and Society by Y. Haila & R. Levins. LondonDocument4 pagesBook Reviews: Humanity and Nature: Ecology, Science and Society by Y. Haila & R. Levins. LondonMosor VladNo ratings yet

- Arne Naess's Concept of The Ecological PDFDocument12 pagesArne Naess's Concept of The Ecological PDFDIURKAZ100% (1)

- Agents of Apocalypse: Epidemic Disease in the Colonial PhilippinesFrom EverandAgents of Apocalypse: Epidemic Disease in the Colonial PhilippinesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Waste and the Wasters: Poetry and Ecosystemic Thought in Medieval EnglandFrom EverandWaste and the Wasters: Poetry and Ecosystemic Thought in Medieval EnglandNo ratings yet

- Nature and NurtureDocument14 pagesNature and NurtureCL PolancosNo ratings yet

- The Culture of Feedback: Ecological Thinking in Seventies AmericaFrom EverandThe Culture of Feedback: Ecological Thinking in Seventies AmericaNo ratings yet

- Human EcologyDocument3 pagesHuman Ecologysandyrevs100% (1)

- Social Forces, University of North Carolina PressDocument9 pagesSocial Forces, University of North Carolina Pressishaq_4y4137No ratings yet

- The Ecosystem Approach: Complexity, Uncertainty, and Managing for SustainabilityFrom EverandThe Ecosystem Approach: Complexity, Uncertainty, and Managing for SustainabilityNo ratings yet

- Roquema - Towards Ecologised Thought Interview With Edgar Morin - qm16Document6 pagesRoquema - Towards Ecologised Thought Interview With Edgar Morin - qm16Hugo Rodrigues CoutoNo ratings yet

- The New Biology: A Battle between Mechanism and OrganicismFrom EverandThe New Biology: A Battle between Mechanism and OrganicismNo ratings yet

- Sustainability 09 00474Document11 pagesSustainability 09 00474martha aulia marcoNo ratings yet

- Ecological EthicsDocument15 pagesEcological EthicsMaria Isabel Ramos MestraNo ratings yet

- Gregory Bateson, Critical Cybernetics and Ecological Aesthetics of Dwelling Jon GoodbunDocument12 pagesGregory Bateson, Critical Cybernetics and Ecological Aesthetics of Dwelling Jon GoodbunsankofakanianNo ratings yet

- Critical Environmental PhilosophyDocument16 pagesCritical Environmental PhilosophyVasudeva Parayana DasNo ratings yet

- Steward, The Concept and Method of Cultural EcologyDocument7 pagesSteward, The Concept and Method of Cultural EcologyMassimo GinebraNo ratings yet

- Module 1. Scope of EcologyDocument22 pagesModule 1. Scope of EcologyVictoire SimoneNo ratings yet

- Fadil's Chapter 2 ProposalDocument11 pagesFadil's Chapter 2 ProposalAdi FirdausiNo ratings yet

- What On Earth.. J. Stan RoweDocument8 pagesWhat On Earth.. J. Stan RoweAbhishek JaniNo ratings yet

- Sociology: Environmental Sociology From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument18 pagesSociology: Environmental Sociology From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediayuvaraj subramaniNo ratings yet

- Evolutionary Theory: A Hierarchical PerspectiveFrom EverandEvolutionary Theory: A Hierarchical PerspectiveRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Étienne Balibar - Human Species As Biopolitical Concept, Radical Philosophy, 2.11 (December 2021)Document10 pagesÉtienne Balibar - Human Species As Biopolitical Concept, Radical Philosophy, 2.11 (December 2021)Josip CmrečnjakNo ratings yet

- Collectively Speaking: Essays on Issues in EthicsFrom EverandCollectively Speaking: Essays on Issues in EthicsNo ratings yet

- Synthesizing Major Perspectives On Environmental Impact MossDocument12 pagesSynthesizing Major Perspectives On Environmental Impact Mossjeanm87No ratings yet

- Contemporary Biomedical Ethics and Environmental Ethics Share A Common Ancestry in The Work of Aldo Leopold and Van Rensselaer PotterDocument8 pagesContemporary Biomedical Ethics and Environmental Ethics Share A Common Ancestry in The Work of Aldo Leopold and Van Rensselaer PotterAmanda Zamora SaadeNo ratings yet

- Foundations of Human EcologyDocument22 pagesFoundations of Human EcologyBo ColemanNo ratings yet

- Man and HIS Environment: Biomedical Knowledge and Social ActionDocument19 pagesMan and HIS Environment: Biomedical Knowledge and Social ActionLizeth gutierrez perezNo ratings yet

- Humans in Their Ecological SettingDocument4 pagesHumans in Their Ecological SettingBenjie Latriz100% (1)

- Eugenics and Protestant Social Reform: Hereditary Science and Religion in America, 1860–1940From EverandEugenics and Protestant Social Reform: Hereditary Science and Religion in America, 1860–1940No ratings yet

- From Complementarity To Obviation IngoldDocument15 pagesFrom Complementarity To Obviation IngoldjohanakuninNo ratings yet

- Potter-Bioethics The Scince of SurvivalDocument28 pagesPotter-Bioethics The Scince of SurvivalNahuelRomeroRojas100% (1)

- Liberation Science: Putting Science to Work for Social and Environmental JusticeFrom EverandLiberation Science: Putting Science to Work for Social and Environmental JusticeNo ratings yet

- Human EcologyDocument24 pagesHuman EcologyVictoriaNo ratings yet

- Choosing A Future For Epidemiology II From Black BoxDocument5 pagesChoosing A Future For Epidemiology II From Black BoxjuanpaNo ratings yet

- Susser 1996 Choosing A Future For Epidemiology PDFDocument4 pagesSusser 1996 Choosing A Future For Epidemiology PDFYesica Tathiana GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Edward Wilson - Sociobiology. The New Synthesis (25th Anniversary Edition)Document910 pagesEdward Wilson - Sociobiology. The New Synthesis (25th Anniversary Edition)Javier Sánchez100% (5)

- Dufour DL. 2006. Biocultural Approaches in Human Biology.Document9 pagesDufour DL. 2006. Biocultural Approaches in Human Biology.Moni SilvyNo ratings yet

- Aupress-Admin,+04 HibbardDocument36 pagesAupress-Admin,+04 HibbardRaissa MendesNo ratings yet

- Darwin and International Relations: On the Evolutionary Origins of War and Ethnic ConflictFrom EverandDarwin and International Relations: On the Evolutionary Origins of War and Ethnic ConflictRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- The Philosophy of Social Ecology: Essays on Dialectical NaturalismFrom EverandThe Philosophy of Social Ecology: Essays on Dialectical NaturalismNo ratings yet

- Ethics in EnvironmentDocument8 pagesEthics in EnvironmentSabari NathanNo ratings yet

- Proof Jan 8 18Document12 pagesProof Jan 8 18Christos SiavikisNo ratings yet

- La Eco y La EcopedimiologiaDocument5 pagesLa Eco y La Ecopedimiologianloscar4179No ratings yet

- Bioethics, The Science of SurvivalDocument28 pagesBioethics, The Science of SurvivalAlejandro Andrés Crespo VillaNo ratings yet

- Biocultural Approach The Essence of Anthropological Study in The 21 CenturyDocument12 pagesBiocultural Approach The Essence of Anthropological Study in The 21 CenturyOntologiaNo ratings yet

- Anthropogenic Rivers: The Production of Uncertainty in Lao HydropowerFrom EverandAnthropogenic Rivers: The Production of Uncertainty in Lao HydropowerNo ratings yet

- What Is Human EcologyDocument23 pagesWhat Is Human EcologybuithanhlongNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B Serological Markers and Plasma DNA ConDocument9 pagesHepatitis B Serological Markers and Plasma DNA ConSerendipity21No ratings yet

- Interpretation of Hepatitis B Serologic Test ResultsDocument1 pageInterpretation of Hepatitis B Serologic Test ResultsMUHAMMAD JAWAD HASSANNo ratings yet

- Director Hertel LetterDocument2 pagesDirector Hertel LetterWWMTNo ratings yet

- Human Sacrifice: Australian Lives Lost To Vaccine ProfiteeringDocument42 pagesHuman Sacrifice: Australian Lives Lost To Vaccine ProfiteeringTim BrownNo ratings yet

- Sars-Cov-2 (Covid 19) Detection (Qualitative) by Real Time RT PCRDocument3 pagesSars-Cov-2 (Covid 19) Detection (Qualitative) by Real Time RT PCRAmar PatilNo ratings yet

- Bullous Pemphigoid Vs Epydermolysis Bullosa Acquisita: Diagnosis and How To DifferentiateDocument12 pagesBullous Pemphigoid Vs Epydermolysis Bullosa Acquisita: Diagnosis and How To DifferentiateIrene Irene100% (1)

- NCP For GastroenteritisDocument8 pagesNCP For GastroenteritisNur SanaaniNo ratings yet

- Oral Diseases Associated With Human Herpes Viruses: Aetiology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis and ManagementDocument9 pagesOral Diseases Associated With Human Herpes Viruses: Aetiology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis and ManagementArif RifaiNo ratings yet

- Immunotherapy: Collected by Muhammad Khalil, KUMS-studentDocument3 pagesImmunotherapy: Collected by Muhammad Khalil, KUMS-studentmuhammad khalilNo ratings yet

- Molecular Biology of The Cell, 5th Edition.20Document3 pagesMolecular Biology of The Cell, 5th Edition.20Manuel Vargas BautistaNo ratings yet

- Subject: - Topics: Cholecystitis: Adult Health NursingDocument17 pagesSubject: - Topics: Cholecystitis: Adult Health NursingUzma KhanNo ratings yet

- Forensic NeuropathologyDocument766 pagesForensic Neuropathologyfrancy100% (3)

- Edukasi Gizi Pada Ibu Hamil Mencegah Stunting Pada Kelas Ibu HamilDocument8 pagesEdukasi Gizi Pada Ibu Hamil Mencegah Stunting Pada Kelas Ibu HamilDella OktaviantiNo ratings yet

- Suresh CertificateDocument1 pageSuresh CertificateSURESH KUMAR KHANWANINo ratings yet

- Scimagojr 2020Document2,453 pagesScimagojr 2020heinz billNo ratings yet

- Ebook Current Medical Diagnosis Treatment 2021 PDF Full Chapter PDFDocument67 pagesEbook Current Medical Diagnosis Treatment 2021 PDF Full Chapter PDFsonia.vanvleck486100% (28)

- Gallium ApaDocument3 pagesGallium Apavedha mungaraNo ratings yet

- Overview of Primary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke - UpToDateDocument15 pagesOverview of Primary Prevention of Coronary Heart Disease and Stroke - UpToDatethanh phung phamNo ratings yet

- Bacillus AnthracisDocument44 pagesBacillus AnthracisBalaji KrishnanNo ratings yet

- Commonucable Diseases EpidemiologyDocument59 pagesCommonucable Diseases Epidemiologyد.شيماءسعيد100% (1)

- Iap Sms Textbook of Community MedicineDocument2 pagesIap Sms Textbook of Community MedicineIndhumathi0% (1)

- Practice Guidelines For The Management of Infectious DiarrheaDocument21 pagesPractice Guidelines For The Management of Infectious DiarrheaJose Alfredo Cruz HernandezNo ratings yet

- COVID 19 and DiabetesDocument3 pagesCOVID 19 and DiabetesAynun JMNo ratings yet

- Subacromial ImpingementDocument19 pagesSubacromial ImpingementIgnatius Rheza SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Aplastic AnemiaDocument21 pagesAplastic AnemiaMichelle Vera GabunNo ratings yet

- Clinical Practice GuidelinesDocument2 pagesClinical Practice GuidelinesEddie WyattNo ratings yet

- Revanggi Ujian OfkomDocument8 pagesRevanggi Ujian OfkomRadit FauzieNo ratings yet

- 2 Assessment of The Immune SystemDocument30 pages2 Assessment of The Immune Systemcoosa liquorsNo ratings yet

- AkhtarandWhite OIE 2003Document12 pagesAkhtarandWhite OIE 2003VEO SOHAGPURNo ratings yet

- NCP CholeraDocument2 pagesNCP CholeraMichael Angelo Garcia RafananNo ratings yet