Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Early Response To COVID-19 in The Philippines: The Philippine Health System and The Threat of Public Health Emer-Gencies

Early Response To COVID-19 in The Philippines: The Philippine Health System and The Threat of Public Health Emer-Gencies

Uploaded by

marronOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Early Response To COVID-19 in The Philippines: The Philippine Health System and The Threat of Public Health Emer-Gencies

Early Response To COVID-19 in The Philippines: The Philippine Health System and The Threat of Public Health Emer-Gencies

Uploaded by

marronCopyright:

Available Formats

Perspective

Early response to COVID-19 in the

Philippines

Arianna Maever L. Amit,a,b Veincent Christian F. Pepitoa,b and Manuel M. Dayritb

Correspondence to Arianna Maever L. (email: alamit@up.edu.ph)

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) with weak health systems are especially vulnerable during the COVID-19

pandemic. In this paper, we describe the challenges and early response of the Philippine Government, focusing on travel

restrictions, community interventions, risk communication and testing, from 30 January 2020 when the first case was

reported, to 21 March 2020. Our narrative provides a better understanding of the specific limitations of the Philippines

and other LMICs, which could serve as basis for future action to improve national strategies for current and future public

health outbreaks and emergencies.

THE PHILIPPINE HEALTH SYSTEM AND the past, as in the case of typhoon Haiyan in 2013.6

THE THREAT OF PUBLIC HEALTH EMER- The typhoon affected 13.3 million people, overwhelm-

GENCIES ing the Government’s capacity to mobilize human and

financial resources rapidly to affected areas.7 Failure

D

espite improvements during the past decade, to deliver basic needs and health services resulted in

the Philippines continues to face challenges disease outbreaks, including a community outbreak of

in responding to public health emergencies gastroenteritis.8 Access to care has improved in recent

because of poorly distributed resources and capacity. years due to an increase in the number of private hos-

The Philippines has 10 hospital beds and six pital beds;5 however, improvements in private sector

physicians per 10 000 people.1,2 and only about facilities mainly benefit people who can afford them, in

2335 critical care beds nationwide.3 The available both urban and rural areas.

resources are concentrated in urban areas, and rural

areas have only one physician for populations up to In this paper, we describe the challenges and early

20 000 people and only one bed for a population of response of the Philippine Government, focusing on

1000.4 Disease surveillance capacity is also unevenly travel restrictions, community interventions, risk com-

distributed among regions and provinces. The primary munication and testing, from 30 January 2020 when

care system comprises health centres and community the first case was reported, to 21 March 2020.

health workers, but these are generally ill-equipped

and poorly resourced, with limited surge capacity, as EARLY RESPONSE TO COVID-19

evidenced by lack of laboratory testing capacity, limited

equipment and medical supplies, and lack of personal Travel restrictions

protective equipment for health workers in both primary

care units and hospitals.5 Local government disaster Travel restrictions in the Philippines were imposed

preparedness plans are designed for natural disasters as early as 28 January, before the first confirmed

and not for epidemics. case was reported on 30 January (Fig. 1a).9 After the

first few COVID-19 cases and deaths, the Government

Inadequate, poorly distributed resources and ca- conducted contact tracing and imposed additional

pacity nationally and subnationally have made it difficult travel restrictions,10 with arrivals from restricted coun-

to respond adequately to public health emergencies in tries subject to 14-day quarantine and testing. While

a

College of Medicine, University of the Philippines Manila, Manila, Philippines.

b

School of Medicine and Public Health, Ateneo de Manila University, Pasig City, Philippines.

Published: 5 February 2021

doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2020.11.1.014

www.wpro.who.int/wpsar WPSAR Vol 12, No 1, 2021 | doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2020.11.1.014 1

Early response to COVID-19 in the Philippines Amit et al

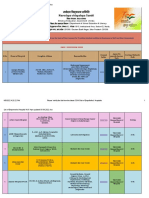

Fig. 1a. New cases of COVID-19 in the Philippines, 30 January–21 March 2020

80

60

Number of new cases

40

20

01 Feb 2020 15 Feb 2020 01 Mar 2020 15 Mar 2020

Community transmission reported Declaration of state of public WHO declares COVID-19

in the Philippines health emergency a pandemic

Fig. 1b. Timeline of key events and developments in the Philippines, 30 January–21 March 2020

Travel restrictions

Hubei Province, China

Mainland China, Hong Kong SAR (China), Macau SAR (China)

Taiwan (China)

Republic Korea (select areas)

Community interventions

Flexible work arrangements

Prohibition of mass gatherings

Suspension of classes

Metro Manila under ECQ

ECQ extended to entire Luzon

Testing

Ramping up of testing capacity

Field testing of local test kits

01 Feb 2020 15 Feb 2020 01 Mar 2020 15 Mar 2020

Community transmission reported Declaration of state of public WHO declares COVID-19

in the Philippines health emergency a pandemic

travel restrictions in the early phase of the COVID-19 only briefly, as the number of confirmed cases increased

response prevented spread of the disease by potentially in the weeks that followed.11 Fig. 1b shows all interven-

infected people, travellers from countries not on the tions, including travel restrictions undertaken before 6

list of restricted countries were not subject to the same March, when the Government declared the occurrence

screening and quarantine protocols. The restrictions of community spread, and after 11 March, when WHO

were successful in delaying the spread of the disease declared COVID-19 a pandemic.

2 WPSAR Vol 12, No 1, 2021 | doi: 10.5365/wpsar. 2020.11.1.014 www.wpro.who.int/wpsar

Amit et al Early response to COVID-19 in the Philippines

Fig. 2. Provinces placed under enhanced community quarantine (ECQ). (2a) The Government declared ECQ in

Metro Manila effective 15 March 2020; (2b) The Government declared ECQ on the entire island of Luzon

effective 17 March 2020.

2a 2b

Community interventions that health systems were not overwhelmed.14 While the

lockdown implemented by the Government applied only

The Government declared “enhanced community quar- to the island of Luzon, local governments in other parts

antine” (ECQ) for Metro Manila between 15 March and of the country followed this example and also locked

14 April (Fig. 2a), which was subsequently extended down. The ECQ gave the country the opportunity to

to the whole island of Luzon (Fig. 2b). The quarantine mobilize resources and organize its pandemic response,

consisted of: strict home quarantine in all households, which was especially important in a country with poorly

physical distancing, suspension of classes and introduc- distributed, scarce resources and capacity.

tion of work from home, closure of public transport

and non-essential business establishments, prohibition Risk communication

of mass gatherings and non-essential public events,

regulation of the provision of food and essential health The Government strengthened and implemented na-

services, curfews and bans on sale of liquor and a tional risk communication plans to provide information

heightened presence of uniformed personnel to enforce on the new disease. The Government conducted daily

the quarantine procedures.12 ECQ – an unprecedented press briefings, sponsored health-related television and

move in the country’s history – was modelled on the Internet advertisements and circulated infographics on

lockdown in Hubei, China, which was reported to have social media. Misinformation and conspiracy theories

slowed disease transmission.13 Region-wide disease about COVID-19 were nevertheless a challenge for a

control interventions, such as quarantining of the entire population that spends more than 10 hours a day on the

Luzon island, were challenging to implement because Internet.15,16 These spread quickly and became increas-

of their scale and social and economic impacts, but ingly difficult to correct. Furthermore, the Government’s

they were deemed necessary to “flatten the curve” so messages did not reach all households, despite access

www.wpro.who.int/wpsar WPSAR Vol 12, No 1, 2021 | doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2020.11.1.014 3

Early response to COVID-19 in the Philippines Amit et al

to health services and information, resulting in limited ness, surveillance and testing capacity in particular is

knowledge of preventive practices, except for hand- a lesson that the Philippines and other LMICs should

washing.17 learn from COVID-19.

Testing Acknowledgements

None

Testing is key to controlling the pandemic but was done

on a small scale in the Philippines. As of 19 March,

Conflict of interests

fewer than 1200 individuals had been tested,11 as only

the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine located in None reported

Metro Manila performed tests and assisted subnational

reference laboratories in testing.18 No positivity rates Funding

for RT-PCR tests were reported until early April 2020.

Because of the limited capacity for testing at the start Not applicable

of the pandemic, the Department of Health imposed

strict protocols in order to ration testing resources while References

ramping up testing capacity. Most tests were conducted

1. Hospital beds (per 1,000 people). Washington, DC: World Bank;

for individuals in urban areas, where the incidence was 2020. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/

highest.19 SH.MED.BEDS.ZS.

2. World Bank open data. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2019.

Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/, accessed 18 March

CONCLUSIONS 2020.

3. Phua J, Faruq MO, Kulkarni AP, Redjeki IS, Detleuxay K, Mend-

At the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the country’s saikhan N, et al. Asian Analysis of Bed Capacity in Critical Care

(ABC) Study Investigators, and the Asian Critical Care Clinical Tri-

initial response lacked organizational preparedness als Group. Critical care bed capacity in Asian countries and re-

to counter the public health threat. The Philippines’ gions. Crit Care Med. 2020;48(5):654–62.

disease surveillance system could conduct contact 4. Human resources for health country profiles: Philippines. Ma-

tracing, but this was overwhelmed in the early phases nila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2013.

Available from: https://iris.wpro.who.int/bitstream/han-

of outbreak response. Similarly, in February, only one

dle/10665.1/7869/9789290616245_eng.pdf.

laboratory could conduct reverse transcriptase polymer-

5. Dayrit M, Lagrada L, Picazo O, Pons M, Villaverde M. The Philip-

ase chain reaction (RT–PCR) testing, so the country pines health system review. New Delhi: WHO Regional Office for

could not rapidly deploy extensive laboratory testing South-East Asia; 2018. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/

for infected cases. In addition, the primary care system handle/10665/274579, accessed 28 August 2020.

of the Philippines did not serve as a primary line of 6. McPherson M, Counahan M, Hall JL. Responding to Typhoon Hai-

defence, as people went straight to hospitals in urban yan in the Philippines. West Pac Surveill Response. 2015 Nov

6;6(Suppl1):1–4. doi:10.5365/wpsar.2015.6.4.HYN_026

areas, overwhelming critical care capacity in the early

7. Santiago JSS, Manuela WS Jr, Tan MLL, Sañez SK, Tong AZU. Of

stages of the COVID-19 pandemic.

timelines and timeliness: lessons from typhoon Haiyan in early

disaster response. Disasters. 2016;40(4):644–67.

In response to the early phase of the pandemic, 8. Ventura RJ, Muhi E, de los Reyes VC, Sucaldito MN, Tayag E.

the Government of the Philippines implemented travel A community-based gastroenteritis outbreak after typhoon Hai-

yan, Leyte, Philippines, 2013. West Pac Surveill Response.

restrictions, community quarantine, risk communication

2015;6(1):1–6.

and testing; however, the slow ramping up of capacities

9. Inter-Agency Task Force for the Management of Emerging Infec-

particularly on testing contributed to unbridled disease tious Diseases. Resolution No. 01. Recommendations for the

transmission. By 15 October, the number of confirmed management of the novel coronavirus situation. Manila: Depart-

cases had exponentially grown to 340,000 of which ment of Health; 2020. Available from: https://www.officialgazette.

gov.ph/downloads/2020/01jan/20200128-IATF-RESOLUTION-

13.8% were deemed active.11 The lack of pandemic NO-1-RRD.pdf, accessed 3 June 2020.

preparedness had left the country poorly defended

10. February files. Manila: Civil Aeronautics Board; 2020. Available

against the new virus and its devastating effects. Invest- from: https://www.cab.gov.ph/announcements/category/febru-

ing diligently and consistently in pandemic prepared- ary-16, accessed 19 March 2020.

4 WPSAR Vol 12, No 1, 2021 | doi: 10.5365/wpsar. 2020.11.1.014 www.wpro.who.int/wpsar

Amit et al Early response to COVID-19 in the Philippines

11. Updates of novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Manila: De- 16. Nicomedes CJC, Avila RMA. An analysis on the panic during

partment of Health; 2020. Available from: https://www.doh.gov. COVID-19 pandemic through an online form. J Affect Disord.

ph/2019-nCov, accessed 16 October 2020. 2020;276:14–22.

12. Marquez C. Palace releases temporary guidelines on Metro Manila 17. Lau LL, Hung N, Go DJ, Ferma J, Choi M, Dodd W, et al. Knowl-

community quarantine. Inquirer News. 14 March 2020. Available edge, attitudes and practices of COVID-19 among income-poor

from: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1241790/palace-releases-tem- households in the Philippines: A cross-sectional study. J Glob

porary-guidelines-on-metro-manila-community-quarantine, ac- Health. 2020;10(1).

cessed 18 April 2020.

13. Leung K, Wu JT, Liu D, Leung GM. First-wave COVID-19 transmis- 18. Nuevo CE, Sigua JA, Boxshall M. Wee Co PA, Yap ME. Scaling

sibility and severity in China outside Hubei after control measures, up capacity for COVID-19 testing in the Philippines. Coronavirus

and second-wave scenario planning: a modelling impact assess- (COVID-19) blog posts collection. London: BMJ Journals; 2020.

ment. Lancet. 2020;395(10233):1382–93. Available from: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmjgh/2020/06/05/scal-

ing-up-capacity-for-covid-19-testing-in-the-philippines/, accessed

14. Wilder-Smith A, Freedman DO. Isolation, quarantine, social dis-

28 August 2020.

tancing and community containment: pivotal role for old-style

public health measures in the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) out- 19. Decision tool for 2019 novel coronavirus acute respiratory disease

break. J Travel Med. 2020;27(2). (2019-nCoV ARD) health event as of January 30, 2020. Manila:

15. Digital 2020: The Philippines. DataReportal – global digital in- Department of Health; 2020. Available from: https://www.doh.

sights. Available from: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital- gov.ph/sites/default/files/health-update/COVID-19-Advisory-No2.

2020-philippines, accessed 28 August 2020. pdf, accessed 28 August 2020.

www.wpro.who.int/wpsar WPSAR Vol 12, No 1, 2021 | doi: 10.5365/wpsar.2020.11.1.014 5

You might also like

- Holt McDougal Florida Larson Algebra 1 PDFDocument431 pagesHolt McDougal Florida Larson Algebra 1 PDFArthur Braga91% (11)

- Roland G-70 Service ManualDocument89 pagesRoland G-70 Service ManualBigg Dady100% (2)

- Introduction To Business Combination - Lesson1Document37 pagesIntroduction To Business Combination - Lesson1Eunice MiloNo ratings yet

- ThesisPresentation PDFDocument19 pagesThesisPresentation PDFIonathanailNo ratings yet

- HCT Covid-19 Response Plan (3 April Update)Document25 pagesHCT Covid-19 Response Plan (3 April Update)Imperial ArnelNo ratings yet

- Covid 19 ReportDocument4 pagesCovid 19 ReportJeancy SenosinNo ratings yet

- Contingency Planning ChecklistDocument36 pagesContingency Planning Checklistpatrickcolmenar5No ratings yet

- Advisory On Recognition and Containment Measures For Second Wave of Covid-19 IN KarnatakaDocument8 pagesAdvisory On Recognition and Containment Measures For Second Wave of Covid-19 IN KarnatakaravindraiNo ratings yet

- KenyaDocument6 pagesKenyaUnnati MouarNo ratings yet

- Stakeholder Engagement Plan SEP Mongolia PEF Support For COVID 19 P174571Document12 pagesStakeholder Engagement Plan SEP Mongolia PEF Support For COVID 19 P174571cipinaNo ratings yet

- Course: Inroduction To Development Studies Instructor: Akhtar Hussain GROUP# 14 Assignment No# 1Document9 pagesCourse: Inroduction To Development Studies Instructor: Akhtar Hussain GROUP# 14 Assignment No# 1MUHAMMAD AHSAN KHALIDNo ratings yet

- The Major Effects of Covid-19 in The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesThe Major Effects of Covid-19 in The PhilippinesMark De JesusNo ratings yet

- Invasive ManagementDocument10 pagesInvasive ManagementMerazel GuadalupeNo ratings yet

- CovidarticleDocument1 pageCovidarticleAngellie LaborteNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Philippines HRP August RevisionDocument55 pagesCOVID-19 Philippines HRP August RevisionJeff Cruz Gregorio100% (1)

- Problem and Advice of Rural Poverty-Alleviation in China Amid The Epidemic of Covid-19 (Victor Mmbengwa and Xiaoshun Qin)Document11 pagesProblem and Advice of Rural Poverty-Alleviation in China Amid The Epidemic of Covid-19 (Victor Mmbengwa and Xiaoshun Qin)Mordecai NdlovuNo ratings yet

- Problem and Advice of Rural Poverty-Alleviation in China Amid The Epidemic of Covid-19Document11 pagesProblem and Advice of Rural Poverty-Alleviation in China Amid The Epidemic of Covid-19Mordecai NdlovuNo ratings yet

- GovernanceDocument3 pagesGovernanceCris Joy BiabasNo ratings yet

- A Nursing Informatics Response To COVIDDocument7 pagesA Nursing Informatics Response To COVIDgygyNo ratings yet

- 2299-Article Text-26374-3-10-20220428Document6 pages2299-Article Text-26374-3-10-20220428anne claire feudoNo ratings yet

- Una Narrativa Crítica de La Preparación y Respuesta de Ecuador A La Pandemia de COVID-19Document4 pagesUna Narrativa Crítica de La Preparación y Respuesta de Ecuador A La Pandemia de COVID-19Jhon LandonNo ratings yet

- Comment: Lancet Infect Dis 2020Document2 pagesComment: Lancet Infect Dis 2020NofiindaNofiINo ratings yet

- 1268 2310 1 SMDocument6 pages1268 2310 1 SMHeru Sutanto KNo ratings yet

- 183-Article Text-698-1-10-20200505Document10 pages183-Article Text-698-1-10-20200505Nailis Sa'adahNo ratings yet

- Policy Brief COVID-19 Impact On The Value Chain Asia June 2020Document10 pagesPolicy Brief COVID-19 Impact On The Value Chain Asia June 2020Nafia AzhariyaNo ratings yet

- UCSPDocument12 pagesUCSPRain Marie DumasNo ratings yet

- Flattening The Curve PDFDocument4 pagesFlattening The Curve PDFRina GuilasNo ratings yet

- Bs Math A-Term Paper-Covid19Document14 pagesBs Math A-Term Paper-Covid19Monica BurbanoNo ratings yet

- Reaction Paper 1 Topic: Coronavirus Disease 2019 Date: March 13, 2020 Covid-19 Global Health CrisisDocument5 pagesReaction Paper 1 Topic: Coronavirus Disease 2019 Date: March 13, 2020 Covid-19 Global Health CrisisFredo TrejoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper - Datiles - Javier - Tobias - Vasquez - Bsn2aDocument9 pagesResearch Paper - Datiles - Javier - Tobias - Vasquez - Bsn2aMari Sheanne M. VasquezNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Department of Education Region IIIDocument19 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Department of Education Region IIIMon Eric LomedaNo ratings yet

- The Life of Miss CoronaDocument6 pagesThe Life of Miss CoronaKlenny BatisanNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Large-Scale Social Restrictions (PSBB) Toward The New Normal Era During COVID-19 Outbreak: A Mini Policy ReviewDocument5 pagesEffectiveness of Large-Scale Social Restrictions (PSBB) Toward The New Normal Era During COVID-19 Outbreak: A Mini Policy ReviewChristian mNo ratings yet

- Article PublicationDocument12 pagesArticle PublicationHarman SinghNo ratings yet

- CASE STUDY. Government ResponsesDocument24 pagesCASE STUDY. Government ResponsesjoloaretaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Mitigation Measures During COVID19 and Risk Benefit Analysis Pakistan 2021Document16 pagesImpact of Mitigation Measures During COVID19 and Risk Benefit Analysis Pakistan 2021Syed Moiz AliNo ratings yet

- Aguado, Emma Angelica B. Section 80 Summative AssessmentDocument3 pagesAguado, Emma Angelica B. Section 80 Summative AssessmentEMMANo ratings yet

- DOH Memo On Vaccination of Adult General PopulationDocument4 pagesDOH Memo On Vaccination of Adult General PopulationRapplerNo ratings yet

- Title: Lessons Learned During The Early Phase of The COVID-19 Pandemic in TheDocument20 pagesTitle: Lessons Learned During The Early Phase of The COVID-19 Pandemic in TheJaico DictaanNo ratings yet

- Uy Et Al. - 2022 - The Impact of COVID-19 On Hospital Admissions For Twelve High-Burden Diseases and Five Common Procedures in The PhiliDocument12 pagesUy Et Al. - 2022 - The Impact of COVID-19 On Hospital Admissions For Twelve High-Burden Diseases and Five Common Procedures in The PhiliFadila RizkiNo ratings yet

- Governance in Times of A Pandemic: The Case of COVID-19: Rhoderick R. SantosDocument19 pagesGovernance in Times of A Pandemic: The Case of COVID-19: Rhoderick R. SantosAnn Gloghienette Orais PerezNo ratings yet

- COVID and Federal Health Systems Paper FinalDocument13 pagesCOVID and Federal Health Systems Paper FinalSharad WagleNo ratings yet

- Position Paper - WHO PhilippinesDocument2 pagesPosition Paper - WHO PhilippinesMonica AnggiNo ratings yet

- Pidsdps 2123Document19 pagesPidsdps 2123Frances Bianca MadrilejosNo ratings yet

- Who PHL Sitrep 81 Covid 19 19 JulyDocument9 pagesWho PHL Sitrep 81 Covid 19 19 JulyJames 5No ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document6 pagesChapter 1mary ann rosendoNo ratings yet

- Gautam Jamdade, Gautamrao Jamdade - 2021 - Modeling and Prediction of COVID-19 Spread in The Philippines by October 13, 2020, by Using T-AnnotatedDocument8 pagesGautam Jamdade, Gautamrao Jamdade - 2021 - Modeling and Prediction of COVID-19 Spread in The Philippines by October 13, 2020, by Using T-AnnotatedZipeng WuNo ratings yet

- Who PHL Sitrep 54 Covid 19 22september2020Document10 pagesWho PHL Sitrep 54 Covid 19 22september2020Alice KrodeNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic: EditorialDocument3 pagesCoronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Pandemic: EditorialBeb HaqNo ratings yet

- Health Policy and Technology: Weiwei Xu, Jing Wu, Lidan CaoDocument10 pagesHealth Policy and Technology: Weiwei Xu, Jing Wu, Lidan CaoArgonne Robert AblanqueNo ratings yet

- Bsed Math 2 - Covid 19Document22 pagesBsed Math 2 - Covid 19Mary Joy Heraga PagadorNo ratings yet

- Prof Jose ChenDocument16 pagesProf Jose ChenRetnayu PrasetyantiNo ratings yet

- Lancet2019 PDFDocument2 pagesLancet2019 PDFSubhangi NandiNo ratings yet

- PHILOSOPHYDocument11 pagesPHILOSOPHYSaloni ChoudharyNo ratings yet

- RIVERA, Jerico - ANTHRO179 - ADVOCACYPROPOSALDocument17 pagesRIVERA, Jerico - ANTHRO179 - ADVOCACYPROPOSALJerico RiveraNo ratings yet

- Covid 19Document16 pagesCovid 19Mazia MansoorNo ratings yet

- Telemedicine After The COVID-19Document61 pagesTelemedicine After The COVID-19ZNo ratings yet

- Kenya Guidelines On Continuity of Community Health Services in TheDocument32 pagesKenya Guidelines On Continuity of Community Health Services in ThesamiirNo ratings yet

- PR 1 PT1 OUTLINE 1lesson 1Document4 pagesPR 1 PT1 OUTLINE 1lesson 1Rosalie CondezaNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines (Address of School) (Name of School)Document3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines (Address of School) (Name of School)siahkyNo ratings yet

- 6006 20017 4 PBDocument7 pages6006 20017 4 PBreniminaryuNo ratings yet

- Health Information Systems AmidDocument2 pagesHealth Information Systems Amidasm obginNo ratings yet

- When Will The COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia End?: Dewi SusannaDocument3 pagesWhen Will The COVID-19 Pandemic in Indonesia End?: Dewi SusannatiaranindyNo ratings yet

- Spool Lift and Loadout ProcedureDocument75 pagesSpool Lift and Loadout ProcedurePhani Kumar G SNo ratings yet

- Manu Oper Monitor Paciente Vitalcare 506N3 CriticareDocument146 pagesManu Oper Monitor Paciente Vitalcare 506N3 CriticareRigoberto Urquijo GarciaNo ratings yet

- Intellectual Property: Media and Information Literacy Lesson 5Document45 pagesIntellectual Property: Media and Information Literacy Lesson 5Jy BaltzNo ratings yet

- PoF Formulae and GraphsDocument4 pagesPoF Formulae and GraphsDiego CarraraNo ratings yet

- Visitor Management SystemDocument39 pagesVisitor Management SystemKeerthi Vasan LNo ratings yet

- Macam Vs GatmaitanDocument4 pagesMacam Vs GatmaitanIvan Montealegre Conchas100% (1)

- 12 Ton Fixed Height Tripod Jack Business Jets: Model 12314SDocument3 pages12 Ton Fixed Height Tripod Jack Business Jets: Model 12314SGenaire LimitedNo ratings yet

- Role of Media in Shaping Public Opinion in PakistanDocument3 pagesRole of Media in Shaping Public Opinion in Pakistannexex52686No ratings yet

- 4 QR Factorization: 4.1 Reduced vs. Full QRDocument12 pages4 QR Factorization: 4.1 Reduced vs. Full QRMohammad Umar RehmanNo ratings yet

- Managing Millennials - A Framework For Improving Attraction, Motivation, and Retention PDFDocument11 pagesManaging Millennials - A Framework For Improving Attraction, Motivation, and Retention PDFZaya AltankhuyagNo ratings yet

- Navodaya Vidayalaya SamitiDocument100 pagesNavodaya Vidayalaya SamitiAnoopNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Writing PromptsDocument8 pagesPersuasive Writing PromptsvivNo ratings yet

- Marvellous Logic Building Asignment - 1Document3 pagesMarvellous Logic Building Asignment - 1Saurabh DhokeNo ratings yet

- SM Spring2017Document60 pagesSM Spring2017Arifin MasruriNo ratings yet

- QM - Master Inspection Characteristic (MIC) GP02Document45 pagesQM - Master Inspection Characteristic (MIC) GP02sapppqmmanloNo ratings yet

- Contract of Service (GAD)Document3 pagesContract of Service (GAD)Kurth MaquizaNo ratings yet

- Modicon Unity Pro Program Languages Structure Ref ManualDocument698 pagesModicon Unity Pro Program Languages Structure Ref Manualobi SalamNo ratings yet

- Inside Pstricks: Timothy Van ZandtDocument10 pagesInside Pstricks: Timothy Van ZandtguiburNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9Document8 pagesChapter 9GODNo ratings yet

- Draft NEP Regulation UG Courses 07012022Document69 pagesDraft NEP Regulation UG Courses 07012022Ka HaNo ratings yet

- TheTradingMantisTools DocumentationDocument3 pagesTheTradingMantisTools DocumentationStock TradingNo ratings yet

- Morrison - Distinguishing Between Forensic Science and Forensic PseudoscienceDocument12 pagesMorrison - Distinguishing Between Forensic Science and Forensic PseudoscienceSara Valencia SánchezNo ratings yet

- Karen Lynn Lacek ResumeDocument4 pagesKaren Lynn Lacek Resumeapi-532679106No ratings yet

- SI3000 Pono Datasheet PDFDocument2 pagesSI3000 Pono Datasheet PDFJose JoseNo ratings yet

- Inspection Certificate: in Accordance With EN 10204 - 3.1Document1 pageInspection Certificate: in Accordance With EN 10204 - 3.1Okan KöksalNo ratings yet

- Dividend StrippingDocument3 pagesDividend StrippingThadakamadla RajanandNo ratings yet