Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Parental Apologies, Empathy, Shame, Guilt, and Attachment: A Path Analysis

Uploaded by

WHOOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Parental Apologies, Empathy, Shame, Guilt, and Attachment: A Path Analysis

Uploaded by

WHOCopyright:

Available Formats

Received 11/15/15

Revised 08/09/16

Accepted 08/09/16

DOI: 10.1002/jcad.12154

Parental Apologies, Empathy,

Shame, Guilt, and Attachment:

A Path Analysis

Jeremy Ruckstaetter, James Sells, Mark D. Newmeyer,

and Daniel Zink

The authors investigated the complex relationships of parental attitudes toward apologies, empathy, shame, guilt, and

the parent’s attachment orientation. Survey responses were obtained from 327 parents. A path analysis of the developed

model demonstrated a close model fit (root-mean-square error of approximation = .07; comparative fit index = .93;

incremental fit index = .94; χ2 = 30.71, p < .001), supporting previous research on apologies as beneficial to relation-

ships. A parent’s proclivity toward apologies, positively influenced by empathy and guilt and negatively influenced by

shame-withdraw behaviors, produced a more secure parent–child attachment.

Keywords: parent, apology, attachment, empathy, guilt

We investigated the complex relationships of parental attitudes sometimes include religious perspectives (Balkin, Freeman, &

toward apologies (PATA), parental empathy, shame, guilt, and Lyman, 2009; Worthington, Jennings, & DiBlasio, 2010). As a

the path of those variables within the parent–child attach- mechanism of communication and as a way of relating to oth-

ment relationship. Parent–child relationships inevitably face ers, apologies are offered in various ways for various reasons.

conflict. Sometimes the parent is the person who exacerbated For example, apologies are offered for various breaches in

the conflict or caused the rupture in the relationship with a interactions, including moral and conventional breaches, but

child (Siegel & Hartzell, 2003). To coach parents through also for incidents such as accidents, interruptions in activities,

the process of repairing a relational rupture, Gottman (1997) or to convey sympathy (Ely & Gleason, 2006).

advocated for the use of an apology. Similarly, Siegel and Most perspectives require an admission of guilt or an ac-

Hartzell (2003) illustrated this process of repair by describing knowledgment of responsibility from the transgressor to the

an apology. Within these approaches, there is an assumption victim (Newman & Kraynack, 2013; Sandage et al., 2000)

that apologies help to restore a relational rupture between a and an expression of regret (Darby & Schlenker, 1982; Reik,

parent and a child. However, there is minimal research on 2010) or remorse (C. Smith & Harris, 2011) to constitute a

parental apologies to guide counselors in their work with genuine apology. P. Davis (2002) stated, “It is intrinsic to a

parents and children. genuine apology that one takes oneself to be in the wrong”

(p. 169), and Tavuchis (1991) clarified that apologies are

Apologies “to someone . . . for something” (p. 13). Remorse does not

necessarily need to be explicitly stated. C. Smith and Harris

Apologies have been explored from various perspectives (2011) suggested that nonverbal expressions of remorse

(e.g., Ashy, Mercurio, & Malley-Morrison, 2010; Ely & may suffice in the communication of an apology. However,

Gleason, 2006; Goffman, 1971) and investigated under taking responsibility and expressing remorse—verbally or

similar constructs and verbiage, such as seeking forgiveness nonverbally—are key aspects of truly apologizing. Apologies

(Sandage, Worthington, Hight, & Berry, 2000) and repentance recognize that rules have been broken and reaffirm the value

(Witvliet, Hinman, Brandt, & Exline, 2011). Apologies are of those rules, and they regulate “social conduct by acknowl-

also mentioned in forgiveness literature and research, which edging the existence of interpersonal obligations” (Darby

Jeremy Ruckstaetter and Daniel Zink, Counseling Department, Covenant Theological Seminary; James Sells and Mark D. New-

meyer, School of Psychology and Counseling, Regent University. Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed

to Jeremy Ruckstaetter, Counseling Department, Covenant Theological Seminary, 12330 Conway Road, Creve Coeur, MO 63141

(e-mail: jeremy.ruckstaetter@covenantseminary.edu).

© 2017 by the American Counseling Association. All rights reserved.

Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95 389

Ruckstaetter, Sells, Newmeyer, & Zink

& Schlenker, 1982, p. 742). Additionally, the transgressor’s a parent or caregiver (Siegel, 2001). A parent’s ability to regu-

motivations play an important role in the delivery and the late his or her emotions and connect with a developing child’s

acceptance of an apology. An apologizer intends “to advance emotional state fosters the child’s neurobiological develop-

the victim’s well-being and affirm the breached value” (N. ment and subsequent behavioral flexibility, affect regulation,

Smith, 2008, p. 142). and executive functioning used to process socioemotional

information (Schore, 1997). This process of repairing ruptures

Attachment between the parent and the developing child shapes the child’s

understanding of the self within relationships, including the

Relational intimacy has been examined from an attachment

capacity to regulate one’s emotions.

framework in children (Bowlby, 1988; Clark & Symons, 2009)

and adults (Fraley, Waller, & Brennan, 2000). Bowlby (1988)

conceptualized the parent–child relationship through attach-

Empathy

ment theory, which indicates early parent–child interactions Broadly, empathy has been described as an individual’s re-

as the model for the child’s subsequent relational interactions actions to another person’s experiences (M. Davis, 1983b).

due to the early formation of the child’s sense of self and other. Empathy, like attachment, is comprised of cognitive and

An attachment framework addresses cognitive, affective, and affective components (M. Davis, 1983b) as well as neuro-

behavioral aspects of development within relationships. Ain- biological processes (Coutinho, Silva, & Decety, 2014). The

sworth (1989) described the behavioral system of interaction affective aspect of empathy involves an observer’s emotional

as comprised of “outward manifestations” and “internal orga- reaction being similar to another person’s emotional state,

nization” (p. 709), anchored in neurological and physiological though distinct from the observer’s own feelings of distress,

responses in the individual. From a cognitive perspective, whereas cognitive aspects of empathy include understanding

Baldwin and Fehr (1995) discussed attachment as a product another person’s perspective (M. Davis, 1983a). Empathy

of activated relational schemas, memories, self-concepts, and formation is a developmental process (Hughes, Tingle, &

relational expectations. From an affective perspective, Preston Swain, 1981), and cognitive empathy increases in ado-

and de Waal (2002) described the parent–child relationship as lescents (Van der Graaff et al., 2014). Empathy promotes

parents and infants who are each mutually and emotionally positive social functioning (M. Davis, 1983b) and moral

affected by the other, and this reciprocity is understood to development (Hogan, 1969), and empathy stimulates altru-

organize the developing infant’s ability to regulate emotions istic motivation to respond to the needs of others (Batson

and other developmental processes. & Shaw, 1991).

The quality of early attachment relationships has been

shown to positively and negatively influence social and psy- Empathy, Apologies, and Attachment

chological functioning later in life. Attuned and responsive

caregiving benefits a child’s attachment (Bowlby, 1988). Attachment and empathy development are interconnected

Children who demonstrated a secure attachment style had through affective, cognitive, and neurobiological processes.

increased positive appraisals of themselves and of the social There is evidence that secure attachment and empathy are pos-

behaviors of others (Clark & Symons, 2009) and increased itively correlated in adult relationships (Joireman, Needham,

social, emotional, and cognitive functions (Siegel, 2001). & Cummings, 2001), and scores for personal and parental

Children who were not securely attached showed increased empathy predict overall attachment scores between parents

aggressiveness toward others (Savage, 2014) and “attach- and children (Black & Leszczynski, 2013). Furthermore, the

ment insecurities are associated with a wide range of mental development of empathy in children is related to parent–child

disorders” (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012, p. 14). attachment and is mediated by emotion regulation (Panfile

From an attachment perspective, disconnection and con- & Laible, 2012). A positive orientation toward apologies is

flict within the parent–child relationship have been referred correlated with a secure attachment style in adults (Ashy et

to as ruptures that require repair from the parent or caregiver al., 2010), and apologies help to repair relationships (Exline,

(Flores, 2006; Siegel & Hartzell, 2003). The ongoing process Deshea, & Holeman, 2007; McCullough, Worthington, & Ra-

of rupture and repair within the parent–child relationship has chal, 1997; Zuccarini, Johnson, Dalgleish, & Makinen, 2013)

ramifications on the child’s neurobiological development, and foster empathy and closeness within relationships (Mc-

ability to self-regulate emotion, and brain maturation, all of Cullough et al., 1997). Apologies are associated with empathy

which occur in an interpersonal context and include social in both the giver of the apology (Howell, Turowski, & Buro,

aspects of development (Schore, 2001). The neurological or- 2012) and the one who receives the apology (McCullough et

ganization of the child’s developing brain is affected by early al., 1997). By contrast, a lack of empathy may inhibit one’s

attachment relationships as a child develops memories and as ability to forgive (Worthington, 1998) and presumably one’s

the mind records the self’s experience in the relationship with propensity to apologize.

390 Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95

Parental Apologies, Empathy, Shame, Guilt, and Attachment

Shame and Guilt A child’s early experiences of apologies shape the devel-

opment and incorporation of the prosocial behavior of apolo-

Parents’ experiences of shame and guilt were also factors in gizing. C. Smith and Harris (2011) offered the perspective

the present study. Shame and guilt are similar constructs with that continuities exist between both the experience and the

overlapping elements (Leith & Baumeister, 1998; Tangney & mechanism of apology from childhood to adulthood. Apolo-

Dearing, 2002). Both are considered moral emotions (Cohen, gies from a parent to a child model numerous social and

Wolf, Panter, & Insko, 2011), although guilt is understood emotional processes within the parent–child relationship,

as having a greater relationship to morality than does shame and apologies create meaning, organization, and connection

(Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Researchers and theorists follow for a parent and a child in the wake of disorganizing ruptures.

two main trajectories when differentiating between shame As a parent engages in an apology, takes responsibility for

and guilt: the self-behavior distinction and the public–private his or her actions, and offers a congruent emotional expres-

distinction (Cohen et al., 2011; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). sion when familial values are transgressed and relational

The public–private distinction understands guilt as resulting breeches occur, the parent models an empathic, remorseful,

from transgressions that remain private or are not heightened and responsible posture toward the child. A child’s experi-

by exposure, whereas shame results from public exposure of ence of receiving a parental apology or apology prompt

one’s action (Cohen et al., 2011). The self-behavior distinc- may account for a child’s sensitivity to apology, and the

tion of shame and guilt understands shame as deriving from a apology process may be influenced by other factors, includ-

negative assessment of one’s self, and guilt as emerging from ing a child’s perception of the genuineness of an apology,

one’s assessment of one’s actions or behaviors (Lewis, 1971; expressed remorse, and the use of nonverbal expressions (C.

Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Leith and Baumeister (1998) Smith & Harris, 2011). A child’s experience of prosocial

found shame-proneness to be correlated with higher personal behaviors and the reparative process of an apology would

distress, whereas guilt-proneness was correlated more highly seemingly parallel the experience of relationally damaging

with cognitive aspects of empathy. Shame, negatively, and behaviors such as aggression and violence. Just as children

guilt, positively, are correlated with apology seeking (Fisher who experience abuse exhibit greater aggression and inse-

& Exline, 2006; Howell et al., 2012). cure attachments (Savage, 2014), children who experience

empathy and apologetic expressions tend toward reproduc-

Parents, Children, and Apologies ing those behaviors and subsequent stronger attachments in

Apology research and literature focused on parents and chil- current and future relationships.

dren is limited. A small number of studies have explored the This study focused on a parent’s orientation toward apolo-

developmental nature of a child’s understanding of apologies, gizing within the parent–child relationship and underlying

pointing toward an understanding of apologies as a learned, variables that promote or impede parental apologies. There

developmental process navigable by young children on an is substantial evidence regarding the relationship among vari-

emotional level (C. Smith, Chen, & Harris, 2010) and entail- ous combinations of the variables discussed above, namely,

ing sociocognitive aspects (Darby & Schlenker, 1982; Ely attachment, shame, guilt, aspects of empathy, and the effects

& Gleason, 2006). Darby and Schlenker (1982) understood of apologies. Within the limited apology literature focused

apologies as an aspect of social–cognitive development and on parents and children, there is an emphasis on a child’s

found that even kindergarten and first-grade students have a developmental understanding and acquisition of the use

basic understanding of apologies. Ely and Gleason (2006) of apologies. However, parental apologies directed toward

examined a child’s understanding and acquisition of apolo- children lack attention within the literature, and it is not

getic language from a linguistic perspective and recognized known how apologies from a parent to a child influence the

the important role parents provide in defining what constitutes parent–child relationship, or what factors might deter a par-

an offense and what offenses require an apology. C. Smith ent’s apology. Considering the positive nature of apologies

et al. (2010) studied children’s emotional understandings to enhance relational functioning (McCullough et al., 1997),

toward an apologetic and an unapologetic transgressor and apologies within the parent–child relationship are an under-

concluded that most young children, as young as 4 and 5 studied phenomenon.

years old, understood within an apology both “the expres- The present study was designed to examine the com-

sion of regret by the transgressor for harm caused, and the plex relationships of parental apologies, parental empathy,

mitigation of the distress of the victim” (p. 742). Also from shame, and guilt, and how these variables influence the

an emotional perspective, C. Smith and Harris (2011) found parent–child attachment relationship. A hypothesized

that the presence of an apology from a transgressing child model was developed based on attachment theory and

to an offended child significantly impacted the emotional the previously cited research, and the model was tested

responses of the offended child. to see if the proposed causal effects among the variables

Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95 391

Ruckstaetter, Sells, Newmeyer, & Zink

were consistent with parents’ reported data. It is hoped Participants were also asked how many children they had

that parents, children, and those who counsel them will (one child, n = 51, 15.6%; two children, n = 146, 44.6%; three

benefit from this study. children, n = 74, 22.6%; four children, n = 38, 11.6%, five or

more children, n = 14, 4.3%). Four participants (1.2%) did not

Method report the number of children they had. Most parents reported

A path analysis was used to investigate a hypothesized model. having a child 12 years of age or younger, but older than 3

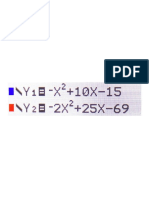

The exogenous variables were empathic concern (EC), per- years (n = 285, 87.2%). Other child ages reported included 15

spective taking (PT), guilt, shame, and PATA. The endogenous years or younger but not under 12 years (n = 20, 6.1%) and 18

variable was attachment represented by low levels of attach- years or younger but not under 15 years (n = 22, 6.7%). Any

ment anxiety and avoidance. There was a particular focus on of the parent participants could also have children older than

the variable of PATA, which was examined as a mediating 18 or multiple children in the varying age ranges.

variable between empathy and attachment, with consideration

Measures

of shame and guilt.

Proclivity to Apologize Measure. The Proclivity to Apologize

Sample Measure (PAM), developed by Howell, Dopko, Turowski,

A convenience sampling method was used to recruit par- and Buro (2011), is based on apology theory and research.

ticipants via the distribution of a web-based survey sent to The measure assesses dimensions of taking responsibility

e-mail lists of various nonprofit organizations, including and a willingness to express remorse for a transgression.

ecclesial organizations, private schools, and youth sports Dimensions of responsibility are assessed by statements

leagues, and the survey was distributed through social such as, “I don’t like to admit to my child that I am wrong.”

media as well. We sought institutional approval and coop- Statements that assess a lack of remorse for the wrong that

eration from each organization, and all data were collected was committed include, “By not apologizing, I can continue

anonymously. The survey consisted of the measures listed to behave as I want.” The eight items are scored on a 7-point

in the following sections, a demographic questionnaire, Likert-type scale with 1 indicating strong disagreement and

and an informed consent form. Participants were asked to 7 indicating strong agreement. For this study, the wording

complete the survey only if they were a biological parent, was adjusted to reflect apologies within the parent–child

stepparent, adoptive parent, or a combination of those relationship and is referred to as the Proclivity to Apologize

categories, and if they had a child between 3 years and 18 Measure for Parents (PAM-P). This measure represents the

years of age. To maximize the independence of the obser- variable PATA. Low scores represent a strong orientation

vations, it was asked that only one parent per household toward apologizing to one’s child. The PAM has previously

complete the survey. demonstrated evidence of construct validity, including an

The sample consisted of 327 parents (25.1% male, n = inverse relationship to narcissism and a positive relationship

82; 74.9% female, n = 245). Participating parents reported with forgiveness and agreeableness (Howell et al., 2011). In

their ages as 21–29 years (n = 10, 3.1%), 30–39 years (n = the current study, the scores on the PAM-P showed favorable

126, 38.5%), 40–49 years (n = 163, 49.8%), and 50 years and reliability (α = .87), consistent with Howell et al. (2012)

older (n = 28, 8.6%). Biological parents outnumbered other and Dunlop, Lee, Ashton, Butcher, and Dykstra (2015),

participants (n = 307, 93.9%). One stepparent participated in who found similar reliability estimates using the original

the study (0.3%), as well as adoptive parents (n = 6, 1.8%) and PAM (α = .79–.84).

parents who reported being in two or more of the parenting Experiences in Close Relationships—Relationship

categories (n = 12, 3.7%). One parent did not identify which Structures Questionnaire. The Experiences in Close

type of parent he or she was. There were 36 single parents Relationships—Relationship Structures Questionnaire

(11%) who participated in the study. The remaining 291 (ECR-RS; Fraley, Heffernan, Vicary, & Brumbaugh, 2011)

parents (89%) reported being married. Of the parents who is a shortened form of the Experiences in Close Relation-

reported being married, 10 (3.1%) reported to be married to ships—Revised scale (Fraley et al., 2000). The ECR-RS

someone other than the child’s biological or adoptive par- was designed to capture the differentiation of attachment

ent, and 281 (85.9 %) were married to the child’s biological across multiple attachment relationships. Fraley et al.

or adoptive parent. A majority of participants reported to (2011) encouraged the adaptation of the scale to assess

be Caucasian (n = 270, 82.6%). Other ethnicities reported particular relationships. The ECR-RS has demonstrated

included African American (n = 30, 9.2%), Hispanic (n = 8, construct validity. For example, the ECR-RS was compared

2.4%), Asian (n = 8, 2.4%), Pacific Islander (n = 1, 0.3%), to other relationship measures that assessed characteristics

Native American (n = 1, 0.3%), other (n = 4, 1.2%), and not such as relational commitment and satisfaction, and when

reported (n = 5, 1.5%). compared to personality traits, the Anxiety subscale correlated

392 Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95

Parental Apologies, Empathy, Shame, Guilt, and Attachment

with neuroticism and the Avoidance subscale was inversely The scales were used to measure the variables of guilt (G-

related to agreeableness (Fraley et al., 2011). Fraley et NBE) and shame-withdraw behaviors (S-W). Cohen et al.

al. (2011) reported Chronbach’s alpha for scores on the (2011) showed evidence of construct validity for the various

ECR-RS subscales when they were adapted for different subscales, comparing the scales to other prosocial mea-

relationships as ranging from .81 to .92. The present study sures, as well as measures of anger, hostility, and unethical

adjusted the measure for parents to children and found behavior. Cohen et al. (2011) reported previous reliability

values of .83 for the ECR-RS Anxiety subscale scores and findings of scores on the S-W subscale (α = .66 and .63) and

.63 for the ECR-RS Avoidance subscale scores. the G-NBE subscale (α = .69 and .71). In the present study,

For the present study, the ECR-RS (Fraley et al., 2011) the S-W (α = .54) and G-NBE (α = .55) subscale scores

was adapted and the wording was modified to align with the of the GASP demonstrated lower reliability than reported

parent–child relationship. Participants were asked to indicate by Cohen et al. (2011). Potential limitations of the GASP

the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with each item are discussed in the following sections. All alpha values,

using a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 means, and standard deviations for the measures used are

(strongly agree). Lower scores on the Anxiety and Avoidance presented in Table 1.

subscales reflect higher levels of attachment security. The

measure, like other attachment measures, is more sensitive Data Analysis

to nonsecurely attached respondents than it is to securely at- A path analysis was performed to assess the model fit of

tached respondents, and it differentiates more clearly those the hypothesized model and to develop a final model using

leaning toward avoidant and anxious tendencies (Fraley et AMOS (Version 22.0). Using path analysis, a researcher can

al., 2011). study a system and the relationships of observed variables

Interpersonal Reactivity Index. The Interpersonal Re- within that system, and the researcher can assume direct

activity Index (IRI) was constructed by M. Davis (1983b). and indirect causal links between variables by examining

The present study uses the EC and PT subscales from the the effects of one variable upon another, while examining

IRI to measure affective and cognitive empathy, respec- whether both variables are “the effect of another cause or

tively. Psychogiou, Daley, Thompson, and Sonuga-Barke causes” (Karadag, 2012, p. 201). Key assumptions within the

(2008) adapted the IRI to be used with the parent–child method include the notion that the theory driving the model

relationship from the parent’s perspective, and their version accurately reflects reality and that the variables and constructs

was used in the present study. The adapted measure will are linear and causal.

represent the EC and PT aspects of parental empathy within We used the chi-square goodness-of-fit measure and other

the present study. The items are assessed on a 5-point fit indices for assessing model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). A

Likert-type scale. The responses range from 0 (does not significant chi-square result suggests misspecification of

describe me well) to 4 (describes me well). Each subscale the model (Chen, Curren, Bollen, Kirby, & Paxton, 2008).

contains seven items for a total of 14 items. Higher scores However, chi-square tests are susceptible to sample size,

represent a higher presence of reported parental empathy. particularly when N = 200 or more (Schumacker & Lomax,

The PT and EC subscales have demonstrated construct

validity through comparison with other measures of social TABLE 1

orientation to self and others (M. Davis, 1983b). M. Davis

(1983a) reported internal reliabilities for the subscale Descriptive Statistics for Variables

scores of the IRI to be between .71 and .77. In the present Variable M SD Possible Range α N

study, the scores on the IRI PT subscale adjusted for parents PAM-P 13.72 6.80 8.0–56.0 .87 314

demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha value of .78. The scores ECR-AV 2.16 0.75 1.0–7.0 .63 317

on the IRI EC subscale adjusted for parents demonstrated ECR-ANX 2.15 1.33 1.0–7.0 .83 322

IRI-PT 18.45 4.58 0.0–28.0 .78 316

a value of .63. IRI-EC 23.94 3.28 0.0–28.0 .63 312

Guilt and Shame Proneness Scale. The Guilt and Shame GASP G-NBE 6.36 0.72 1.0–7.0 .55 318

Proneness Scale (GASP; Cohen et al., 2011) is a scenario- GASP S-W 2.41 0.93 1.0–7.0 .54 318

based measure designed to assess emotional traits of guilt Note. PAM-P = Proclivity to Apologize Measure for Parents; ECR-AV =

and shame. The subscales used for analysis in the current Experiences in Close Relationships, Avoidance subscale; ECR-ANX

study include the Guilt–Negative Behavior-Evaluation (G- = Experiences in Close Relationships, Anxiety subscale; IRI-PT =

Interpersonal Reactivity Index, Perspective Taking; IRI-EC = Inter-

NBE) subscale and the Shame–Withdraw (S-W) subscale.

personal Reactivity Index, Empathic Concern; GASP G-NBE = Guilt

Scores on the G-NBE and S-W subscales have previously and Shame Proneness Scale, Guilt–Negative Behavior-Evaluation

predicted PAM scores (Dunlop et al., 2015). Higher scores subscale; GASP S-W = Guilt and Shame Proneness Scale, Shame–

on the GASP represent a higher presence of shame and guilt. Withdraw subscale.

Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95 393

Ruckstaetter, Sells, Newmeyer, & Zink

2010). In such cases, researchers are led to consider other 2001). The analysis for the present study relied on the ML

fit indices. Various indices and ranges of cutoff values have estimation. In the present study, missing data for each measure

been promoted as indicative of a model fit. The root-mean- were minimal (< 5%). The IRI PT subscale was missing 11

square error of approximation (RMSEA) has been described cases (3.4%), and the IRI EC subscale was missing 15 cases

as indicating a poor fit if greater than .10, a mediocre fit (4.6%). The G-NBE and the S-W subscales of the GASP were

from .08 to .10, and a close fit from .05 to .08, and cutoff both missing nine cases (2.8%). The PAM-P was missing nine

points of less than .06 or .05 have been proposed to indicate cases (2.8%). The ECR-RS Avoidant subscale was missing

a good fit (Byrne, 2001; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Schumacker nine cases (2.8%), and the ECR-RS Anxiety subscale was

& Lomax, 2010). Other measures, such as the incremental missing five cases (1.5%).

fit index (IFI) and the comparative fit index (CFI), have

been described as indicating a good fit with cutoff points Results

of .90 or .95 (Byrne, 2001; Schumacker & Lomax, 2010).

Efforts to identify universal cutoffs are discouraged as a Results of the chi-square and three standard fit indices are

single way of assessing model fit (Chen et al., 2008). Due presented for each model. The hypothesized model (see

to varying complexities in models and sensitivity to sample Figure 1) demonstrated a close fit (RMSEA = .08; CFI =

size, researchers are encouraged to assess multiple indices .93; IFI = .93; χ2 = 32.85, p < .001; N = 327). A slightly

and criteria when assessing model fit (Chen et al., 2008; improved model, the final model (see Figure 2), also

Schumacker & Lomax, 2010). “Ultimately, a researcher demonstrated a close fit (RMSEA = .07; CFI = .93; IFI =

must combine these statistical measures with human judg- .94; χ2 = 30.71, p < .001; N = 327). The final model was

ment when reaching a decision about model fit” (Chen et developed by adding a correlation to the shame and guilt

al., 2008, p. 491). variables and by excluding the path from parental empathy

Similarly, various ranges and rationale for an adequate to S-W. It was determined that there were no problems due

sample size have been proposed. Haenlein and Kaplan (2004) to multicollinearity. Pearson correlation coefficients are

cited literature which recommended that a minimum sample presented in Table 2.

size of 100 or 200 cases should be achieved. Other acceptable In both the hypothesized model and the final model, the

ranges require a minimum of 10 to 20 cases per parameter path from parental empathy to PATA reflected a positive

(Kline, 2016). The present study included 24 parameters and relationship between the variables. High scores on parental

a sample size of 327, thereby meeting an acceptable sample empathy represented a high presence of empathy and low

size under various ranges. scores on PATA represented a high proclivity to apologize.

Missing data should be addressed when conducting em- Thus, the path coefficient is a negative value because of the

pirical research (Byrne, 2001). Ad hoc methods of dealing inverse scoring of the measures, but it represents a positive

with incomplete data are discouraged (Byrne, 2001; Enders relationship and is displayed as such in Figures 1 and 2. The

& Bandalos, 2001). AMOS uses a maximum likelihood path demonstrated that a higher presence of parental empathy

(ML) estimation for treating missing data (Byrne, 2001). positively influenced PATA.

This theoretical approach is advocated over other methods of Parental empathy influenced a parent’s reported guilt,

navigating missing data (Byrne, 2001; Enders & Bandalos, and guilt influenced PATA. Again, the numerical value of

Shame–

Empathic

Withdraw Avoidance

Concern

(–.20)

(–.06)

(.71) (.51)

(.53) Parental Attitudes (.65)

Empathy Attachment

Toward Apologies

(.76) (.52)

(.20)

(.09)

Perspective

Anxiety

Taking G-NBE

FIGURE 1

Hypothesized Model

Note. Values in parentheses are the path coefficients. G-NBE = Guilt–Negative Behavior-Evaluation.

394 Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95

Parental Apologies, Empathy, Shame, Guilt, and Attachment

(–.10) Shame–

Empathic

Withdraw Avoidance

Concern

(–.21)

(.71) (.51)

Parental Attitudes (.65)

Empathy Attachment

(.53) Toward Apologies

(.77) (.52)

(.19)

(.09)

Perspective

Anxiety

Taking G-NBE

FIGURE 2

Final Model

Note. Values in parentheses are the path coefficients. G-NBE = Guilt–Negative Behavior-Evaluation.

the path between G-NBE and PATA was negative because empathy, S-W, and guilt, had a substantial positive effect

the scores were inversely related. However, a higher pres- on a parent’s reported attachment to a child.

ence of trait guilt positively influenced a higher proclivity

to apologize to one’s child, so this was represented with Discussion

a positive path coefficient in Figures 1 and 2. S-W was

negatively related to PATA and negatively related to pa- The relationships of the variables within the final model

rental empathy. The value of the path from S-W to PATA (Figure 2) demonstrated that parental attitudes in favor of

was represented in Figures 1 and 2 as negative to adjust apologies produce more secure parent–child attachment

for the inverted scoring of the measures used to assess relationships. The final model begins with the parents’ abil-

those variables. Shame and guilt also demonstrated a small ity to empathize with their child and is influenced by the

correlation within the model, which improved the overall parents’ experience of trait guilt and S-W behaviors, which

model fit. This correlation is consistent with other research leads to parental apologies and a perception of a more secure

on shame, guilt, and apologies (Howell et al., 2012). In the attachment, as evidenced by a less anxious and less avoidant

hypothesized model, parental empathy showed a minimal attachment orientation toward the child. The final model fits

effect on S-W. The model fit improved slightly when this with previous research with adults, which has shown that

path was removed from the model. In summary, the path apologies help to repair and strengthen close relationships

from PATA, when considering the influence of parental (Zuccarini et al., 2013). Contributing to an understanding

TABLE 2 of apologies in the parent–child relationship, the present

study demonstrated that parental empathy, feelings of guilt,

Pearson Correlations and parental apologies are beneficial to parents’ attachment

orientation toward their child, and S-W behaviors hinder

Variable 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

the process. Due to the limitations that occur when using a

1. PAM-P —

2. ECR-AV .33** — convenience sampling method to collect data, conclusions

3. ECR-ANX .33** .27** — should be considered tentatively.

4. IRI-PT –.41** –.30** –.23** — For apologies to benefit a parent’s attachment to a child,

5. IRI-EC –.40** –.29** –.17** .54** —

6. GASP G-NBE –.19** –.20** –.14* .14* .14* — there is an assumption that the apology would need to be

7. GASP S-W .23** .03 .20** –.02 –.05 –.11 — consistent with the literature’s description of an apology,

Note. PAM-P = Proclivity to Apologize Measure for Parents; ECR- namely that it includes an admission of moral responsibil-

AV = Experiences in Close Relationships, Avoidance subscale; ity or wrongdoing, as well as an expression of remorse.

ECR-ANX = Experiences in Close Relationships, Anxiety subscale; The PAM-P used in this study is based on an admission of

IRI-PT = Interpersonal Reactivity Index, Perspective Taking; IRI-EC responsibility and a display of remorse, and this study as-

= Interpersonal Reactivity Index, Empathic Concern; GASP G-NBE

sessed the parent’s orientation toward apology in conjunction

= Guilt and Shame Proneness Scale, Guilt–Negative Behavior-

Evaluation subscale; GASP S-W = Guilt and Shame Proneness with parental empathy, guilt, and aspects of shame. These

Scale, Shame–Withdraw subscale. variables exclude the notion of manipulative and self-

*p < .05. **p < .01. serving motives within the model. Parental apologies that

Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95 395

Ruckstaetter, Sells, Newmeyer, & Zink

foster a more secure attachment orientation to one’s child based measures, though useful for measuring shame and guilt,

would seem to come from an orientation of contrition that are based on differing value systems for which respondents

recognizes one’s guilt and is motivated by compassion and may or may not feel guilt or shame. For example, one question

care for one’s child. Apologies are one method of attuning in the S-W subscale assessed withdraw behaviors when an

to and regulating the parent–child relationship when rup- uninvited guest comes to one’s messy house. Yet, respondents

tures occur. A parent’s ability to understand, to feel, and to may feel both guilt and shame for the messy house, or they

behaviorally navigate relational distance during and after a may not place any value on a messy or clean house and feel

rupture is influenced by parental empathy, the parent’s nega- no shame or guilt.

tive emotions (guilt and shame), and approach behaviors like Shame responses often manifest as withdraw behaviors,

apologizing. The confluence of these cognitive, affective, but can also be externalized as aggression or anger (Tangney

and behavioral tendencies were shown to benefit the parent’s & Dearing, 2002). For shame-prone individuals, it is possible

attachment perspective. that the capacity for empathy is overwhelmed by the experi-

Empathy positively contributed to the path of parental ence of shame, which leads to self-protecting behaviors like

apologies and a secure attachment orientation to one’s child. aggression and withdraw in an effort to avoid the negative

When parents reported higher cognitive and affective parental experience of shame. Parents who exhibit dysregulated or

empathy, the parent participants also reported a more secure extreme shame reactions may tend toward withdraw, thus

attachment orientation to their child. The path from empathy neglecting a child’s needs, or they may externalize the shame

to attachment was positively influenced by a parent’s experi- by displaying aggressive tendencies toward a child, or both.

ence of guilt and PATA. Avoiding or not engaging in S-W However, parents who are able to regulate those emotions

behaviors also contributed to PATA and to attachment. These may be better able to retain the empathic orientation toward

results contribute to the body of knowledge on parental at- their child and pursue relationship-improving interactions,

tachment motivations and parental attuning behaviors toward like apologizing.

children beyond infancy. A parent’s ability to regulate emotions may be a contribut-

The present study demonstrated that a parent’s tendency ing variable to the model that was not assessed in the present

to experience guilt (G-NBE) mediates the process between study, though a degree of emotion regulation can be assumed

parental empathy and apology, and that parental empathy, to contribute to the final model. The variables of empathy,

guilt, and PATA lead to a more secure attachment with attachment, and prosocial behaviors have been linked to the

one’s child. This is consistent with other research assess- ability to regulate emotions (Panfile & Laible, 2012). In the

ing the positive nature of apologies in adult relationships present study, the sample was skewed toward demonstrat-

(Ashy et al., 2010; Exline et al., 2007; McCullough et al., ing high parental empathy, a high proclivity to apologize,

1997; Zuccarini et al., 2013), and the influence of empa- and a tendency toward secure attachment, all suggestive of

thy and guilt on one’s proclivity to apologize (Howell et an ability to regulate one’s emotions. This may be another

al., 2012). S-W behaviors negatively influenced PATA. reason explaining why the path from empathy to shame did

To apologize is to expose one’s guilt, which may be too not contribute to the final model. Participants who reported

shame inducing of an experience for some parents. Parents a high degree of parental empathy may experience shame but

who feel intense shame, despite the presence of guilt or also may possess the ability to regulate shame reactions and

empathy, would seemingly apologize less and may resort remain empathic toward the child. Overall, the study sup-

to self-justification, avoidance, aggression, or even blam- ports the notion that parents who are able to work through the

ing a child for the transgression or incident. If a parent emotions of shame and guilt, avoid withdraw behaviors, and

can work through the shame response, recognize guilt, and respond empathically to their child in prosocial ways, such

apologize to the child, the parent would begin to develop as apologizing, achieve a more secure attachment orientation

a more secure attachment with the child, which benefits toward their child.

both the parent and the child.

By eliminating the path from empathy to S-W in the pres- Implications of Parental Apologies for Children

ent study, the overall model fit improved slightly. If a lower This study explored factors that influence parental apologies

disposition toward empathy is indeed a contributor to a higher and the parent’s attachment benefits that occur when a par-

experience of shame as previous research indicates (Tangney ent is willing to consider apologizing to a child. However,

& Dearing, 2002), then one explanation for the present study’s within attachment theory, it is assumed that reciprocity exists

results is that the S-W measure from the GASP uses scenarios in the parent–child relationship (Sroufe & Waters, 1977), and

that articulate withdraw behaviors, but may not differentiate that parents who are more attuned to their child’s emotional

between shame and guilt and may use scenarios that are not and cognitive state are better able to care for and nurture their

shame- or guilt-inducing for some respondents. Scenario- child, fostering a mutually reinforcing attachment pattern that

396 Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95

Parental Apologies, Empathy, Shame, Guilt, and Attachment

benefits both parent and child. Panfile and Laible (2012) parent in comparison with the child could be leveraged to

claimed a reciprocal relationship exists in the parent–child begin the repair process.

relationship concerning the child’s experience of receiving A parent’s ability to self-regulate negative guilt and

and displaying relational security, empathy, and prosocial shame experiences will improve his or her relational re-

behaviors, and they stated that children learn to “regulate sponding to the child and advance the apology process.

their emotions after repeated instances of the sensitive By helping parents to identify shame-induced reactions,

responding of their caregivers” (p. 15). As well, previous counselors can help parents develop alternative responses

research has linked empathy and attachment (Black & toward their child. Equally, naming and exploring a par-

Leszczynski, 2013), and a lack of parental empathy has ent’s feelings of guilt in relation to family values can assist

been associated with aggression, abuse, and less prosocial the parent in moving toward consideration of an apology.

responding (Wiehe, 1997). Furthermore, a parent’s capacity Counselors must be aware of their own values and neither

for attachment is important to foster a child’s ability to attach assume a parent’s guilt over a rupture nor dismiss feelings

within relationships (Zilberstein & Messer, 2010). Although of guilt or “shoulds,” but they can carefully assist a parent

the present study demonstrated that a parent’s empathic in evaluating feelings of guilt while working within the fam-

reaction to a child positively contributes to that parent’s use ily’s expressed value system to facilitate the repair process

of apologies and the parent attachment perspective, when around interpersonal transgressions.

considering additional attachment theory and research, it Lastly, guiding a parent through the apology pro-

can be assumed that parental empathy and apologies offered cess includes helping the parent take responsibility

to repair relational ruptures will be beneficial to children for his or her actions and express regret or remorse to

as well. Attuned responses, such as apologies from parents the child for the transgression. Parents will differ in

to children—even at a young age—would help to integrate how they def ine transgressions that require an apology.

the child’s increasing cognitive understanding of self and For example, some parents may determine that yelling at

other in social relationships, as well as the child’s ability to their child or raising their voice is a transgression worthy

self-regulate affective responses and to develop the capac- of apology. In other families, raised voices may occur often

ity to appropriately convey empathy and offer apologies and not necessitate an apology. Counselors can explore and

when needed. discuss the interpersonal transgression and rupture in rela-

tion to the family’s values and suggest or even recommend

Implications for Counseling the possibility of apology as a method of moving beyond

When navigating clinically significant issues that involve ruptures toward a more secure relationship, which benefits

conflicts between parents and children, or as conflicts and both parents and children.

ruptures arise in the course of clinical work, counselors use

discernment and empirical evidence as they help those who Limitations and Future Research

are entrusted to their care. Brief clinical suggestions are Apologies are one way to create strong and meaningful

offered below, and it is hoped that counselors will further bonds with one’s child. This study makes a contribution to

transform the information from this study into practical in- the literature on apology and, more specifically, to PATA

terventions when working with attachment ruptures between and the parent–child relationship. Additional research

parents and children. needs to be conducted to enhance counselors’ and re-

To facilitate an apology process with the goal of repairing searchers’ understanding of the phenomenon and process

attachment ruptures, a counselor can begin with empathy of apologies between parents and children. Researchers

development around the rupture within the relationship. The could consider qualitative and experimental approaches,

parent’s ability to understand the child’s perspective and as well as replication studies with other populations or

ability to experience the child’s emotional pain surrounding different variables.

a particular relational rupture are possible focal points that The present study is limited by the homogeneity of the

address both cognitive and affective aspects of empathy. sample. The sample consisted of 93.9% biological parents.

Additionally, through modeling empathy and providing In an era in which children are frequently being raised by

relational attunement in therapy, counselors can help family caregivers other than biological parents (stepparents, grand-

members experience empathy, which may further stimulate parents, adoptive parents, etc.), these findings should be

the parent–child repair process. No doubt the parent may extended to include these family constellations. The sample

also feel pain and frustration when navigating difficulties population all lived in the United States, so additional research

with an obstinate child or a pernicious adolescent. Perhaps is needed to begin to apply the conclusions cross-culturally.

there is much for the child or teenager to apologize for as Further research is also needed to better understand the

well. Hopefully and normally, however, the maturity of the impact of apologies within parent–child relationships

Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95 397

Ruckstaetter, Sells, Newmeyer, & Zink

that are less securely attached. The convenience sampling Cohen, T., Wolf, S., Panter, A., & Insko, C. (2011). Introduc-

method used for data collection most certainly limited the ing the GASP scale: A new measure of guilt and shame

spectrum of responses. The participants generally had an proneness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

empathic orientation toward their child, generally had a 100, 947–966. doi:10.1037/a0022641

proclivity to apologize, and generally reported secure attach- Coutinho, J., Silva, P., & Decety, J. (2014). Neurosciences,

ments. It stands to reason that parents who are invested in empathy, and healthy interpersonal relationships: Re-

the parenting process would have more secure attachments cent findings and implications for counseling psychol-

and would be more willing to participate in a survey study- ogy. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 61, 541–548.

ing the parent–child relationship. Parents with less secure doi:10.1037/cou0000021

attachments or parents who are ambivalent, disinterested, or Darby, B., & Schlenker, B. (1982). Children’s reactions to

neglectful within the parent–child relationship would most apologies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

likely have been less inclined to complete the survey. Ad- 43, 742–753.

ditionally, perhaps alternative measures could better capture Davis, M. (1983a). The effects of dispositional empathy

larger differences among participants. However, this study on emotional reactions and helping: A multidimen-

has offered a contribution toward understanding variables sional approach. Journal of Personality, 51, 167–184.

that contribute to the apology process and the benefits of doi:10.1111/1467-6494.ep7383133

apologies from parents to children. Davis, M. (1983b). Measuring individual differences in em-

pathy: Evidence for a multi-dimensional approach. Jour-

References nal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113–126.

doi:10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

Ainsworth, M. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Davis, P. (2002). On apologies. Journal of Applied Philoso-

Psychologist, 44, 709–716. phy, 19, 169–173. doi:10.1111/1468-5930.00213

Ashy, M., Mercurio, A., & Malley-Morrison, K. (2010). Apol- Dunlop, P., Lee, K., Ashton, M., Butcher, S., & Dykstra, A.

ogy, forgiveness, and reconciliation: An ecological world (2015). Please accept my sincere and humble apologies:

view framework. Individual Differences Research, 8, 17–26. The HEXACO model of personality and the proclivity to

Baldwin, M., & Fehr, B. (1995). On the instability of attach- apologize. Personality and Individual Differences, 79,

ment style ratings. Personal Relationships, 2, 247–261. 140–145. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.004

doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.1995.tb00090.x Ely, R., & Gleason, J. (2006). I’m sorry I said that: Apologies

Balkin, R., Freeman, S., & Lyman, S. (2009). Forgiveness, rec- in young children’s discourse. Journal of Child Language,

onciliation, and mechila: Integrating the Jewish concept of 33, 599–620. doi:10.1017/S0305000906007446

forgiveness into clinical practice. Counseling and Values, 53, Enders, C., & Bandalos, D. (2001). The relative performance

153–160. doi:10.1002/j.2161-007X.2009.tb00121.x of full information maximum likelihood estimation for

Batson, C., & Shaw, L. (1991). Evidence for altruism: Toward missing data in structural equation models. Educational

a pluralism of prosocial motives. Psychological Inquiry, 2, Psycholog y Papers and Publications, 64, 430–457.

107–122. doi:10.1207/S15328007SEM0803_5

Black, K., & Leszczynski, J. (2013). Development of child at- Exline, J., Deshea, L., & Holeman, V. T. (2007). Is apology

tachment in relation to parental empathy and age. Psi Chi worth the risk? Predictors, outcomes, and ways to avoid

Journal of Psychological Research, 18, 67–73. regret. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26,

Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Parent–child attachment and 479–504. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.4.479

healthy human development. New York, NY: Basic Books. Fisher, M., & Exline, J. (2006). Self-forgiveness versus

Byrne, B. (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: excusing: The roles of remorse, effort, and acceptance of

Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Mahwah, responsibility. Self and Identity, 5, 127–146. doi:10.1080

NJ: Erlbaum. /15298860600586123

Chen, F., Curren, P., Bollen, K., Kirby, J., & Paxton, P. (2008). Flores, P. (2006). Conflict and repair in addiction treat-

An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points ment: An attachment disorder perspective. Journal of

in the RMSEA test statistic in structural equation model- Groups in Addiction and Recovery, 1, 5–26. doi:10.1300/

ing. Sociological Methods and Research, 36, 462–494. J384v01n01_02

doi:10.1177/0049124108314720 Fraley, R., Heffernan, M., Vicary, A., & Brumbaugh, C.

Clark, S., & Symons, D. (2009). Representations of attach- (2011). The Experiences in Close Relationships—Rela-

ment relationships, the self, and significant others in middle tionship Structures Questionnaire: A method for assessing

childhood. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and attachment orientations across relationships. Psychologi-

Adolescent Psychiatry, 18, 316–321. cal Assessment, 23, 615–625. doi:10.1037/a0022898

398 Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95

Parental Apologies, Empathy, Shame, Guilt, and Attachment

Fraley, R., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item Panfile, T., & Laible, D. (2012). Attachment security and child’s

response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult empathy: The mediating role of emotion regulation. Merrill-

attachment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Palmer Quarterly, 58, 1–21.

78, 350–365. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.78.2.350 Preston, S., & de Waal, F. (2002). Empathy: Its ultimate and

Goffman, E. (1971). Relations in public. New York, NY: Harper proximate bases. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 25, 1–20.

Colophon Books. Psychogiou, L., Daley, D., Thompson, M., & Sonuga-Barke,

Gottman, J. (1997). Raising an emotionally intelligent child: E. (2008). Parenting empathy: Associations with di-

The heart of parenting. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster. mensions of parent and child psychopathology. British

Haenlein, M., & Kaplan, A. (2004). A beginner’s guide to Journal of Developmental Psychology, 26, 221–232.

partial least squares analysis. Understanding Statistics, 3, doi:10.1348/02615100X238582

283–297. doi:10.1207/s15328031us0304_4 Reik, B. (2010). Transgressions, guilt, and forgiveness: A model

Hogan, R. (1969). Development of an empathy scale. Jour- of seeking forgiveness. Journal of Psychology and Theology,

nal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 33, 307–316. 38, 246–254.

doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.08.010 Sandage, S., Worthington, E., Hight, T., & Berry, J. (2000).

Howell, A., Dopko, R., Turowski, J., & Buro, K. (2011). The Seeking forgiveness: Theoretical context and an initial

disposition to apologize. Personality and Individual Dif- empirical study. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 28,

ferences, 51, 509–514. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2011.05.009 21–35.

Howell, A., Turowski, J., & Buro, K. (2012). Guilt, empathy, Savage, J. (2014). The association between attachment, parental

and apology. Personality and Individual Differences, 53, bonds and physically aggressive and violent behavior: A

917–922. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.06.021 comprehensive review. Aggression and Violent Behavior,

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for f it in- 19, 164–178. doi:10.1016/j.avb.2014.02.004

dexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional Schore, A. N. (1997). Early organization of the nonlinear right

c r i t e r i a ve r s u s n ew a l t e r n a t ive s . S t r u c t u ra l E q u a - brain and development of a predisposition to psychiatric

tion Modeling: A Mulitdisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. disorders. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 595–631.

doi:10.1080/10705519909540118 doi:10.1017/S0954579497001363

Hughes, R., Tingle, B., & Swain, D. (1981). Development of Schore, A. N. (2001). Contributions from the decade of the

empathic understanding in children. Child Development, brain to infant mental health: An overview. Infant Mental

52, 122–128. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.ep8864501 Health Journal, 22, 1–6.

Joireman, J., Needham, T., & Cummings, A. (2001). Rela- Schumacker, R., & Lomax, R. (2010). A beginner’s guide to

tionships between dimensions of attachment and empa- structural equation modeling (3rd ed.). New York, NY:

thy. North American Journal of Psychology, 3, 63–80. Routledge.

doi:10.1080/14616730600585292 Siegel, D. J. (2001). Toward an interpersonal neurobiology of the

Karadag, E. (2012). Basic features of structural equation developing mind: Attachment relationships, “mindsight,” and

modeling and path analysis with its place and importance in neural integration. Infant Mental Health Journal, 22, 67–94.

educational research and methodology. Bulgarian Journal Siegel, D. J., & Hartzell, M. (2003). Parenting from the inside

of Science and Education Policy, 6, 194–212. out: How a deeper self-understanding can help you raise

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural children who thrive. New York, NY: Tarcher.

equation modeling (4th ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. Smith, C., Chen, D., & Harris, P. (2010). When the happy vic-

Leith, K., & Baumeister, R. (1998). Empathy, shame, guilt, and timizer says sorry: Children’s understanding of apology and

narratives of interpersonal conflicts: Guilt-prone people are emotion. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 28,

better at perspective taking. Journal of Personality, 66, 1–37. 727–746. doi:10.1348/026151009X475343

Lewis, H. (1971). Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York, NY: Smith, C., & Harris, P. (2011). He didn’t want me to feel

International Universities Press. sad: Children’s reactions to disappointment and apology.

McCullough, M. E., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Rachal, K. Social Development, 21, 215–228. doi:10.1111/j.1467-

C. (1997). Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships. 9507.2011.00606.x

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 321–336. Smith, N. (2008). I was wrong: The meanings of apologies. New

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. (2012). An attachment perspective York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

on psychopathology. World Psychiatry, 11, 11–15. Sroufe, L., & Waters, E. (1977). Attachment as an organi-

Newman, L., & Kraynack, L. (2013). The ambiguity of a zational construct. Child Development, 48, 1184–1199.

transgression and the type of apology influence immedi- doi:10.1111/1467-8624.ep10398712

ate reactions. Social Behavior and Personality, 4, 31–46. Tangney, J., & Dearing, R. (2002). Shame and guilt. New York,

doi:10.2224/sbp.2013.41.1.31 NY: Guilford Press.

Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95 399

Ruckstaetter, Sells, Newmeyer, & Zink

Tavuchis, N. (1991). Mea culpa: A sociology of apology and Worthington, E. (1998). An empathy–humility–commitment

reconciliation. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. model of forgiveness applied within family dyads. Journal

Van der Graaff, J., Branje, S., De Wied, M., Hawk, S., Meeus, of Family Therapy, 20, 59–76. doi:10.1111/1467-6427.00068

W., & Van Lier, P. (2014). Perspective taking and empathic Worthington, E., Jennings, D., & DiBlasio, F. (2010). Interven-

concern in adolescence: Gender differences in develop- tions to promote forgiveness in couple and family context:

mental changes. Developmental Psychology, 50, 881–888. Conceptualization, review, and analysis. Journal of Psychol-

doi:10.1037/a0034325 ogy and Theology, 38, 231–245.

Wiehe, V. (1997). Approaching child abuse treatment from Zilberstein, K., & Messer, E. A. (2010). Building a secure base:

the perspective of empathy. Child Abuse and Neglect, 21, Treatment of a child with disorganized attachment. Clinical So-

1191–1204. doi:10.1016/S0145-2134(97)00094-X cial Work Journal, 38, 85–97. doi:10.1007/s10615-007-0097-1

Witvliet, C., Hinman, N., Brandt, T., & Exline, J. (2011). Re- Zuccarini, D., Johnson, S., Dalgleish, T., & Makinen, J. (2013).

sponding to our own transgressions: An experimental writing Forgiveness and reconciliation in emotionally focused therapy

study of repentance, offense rumination, self-justification, for couples: The client change process and therapist interven-

and distraction. Journal of Psychology and Christianity, 30, tions. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 39, 148–162.

223–238. doi:10.1111/j.1752-0606.2012.00287.x

400 Journal of Counseling & Development ■ October 2017 ■ Volume 95

Copyright of Journal of Counseling & Development is the property of Wiley-Blackwell and

its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the

copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email

articles for individual use.

You might also like

- Mrvoljak Theodoropoulou Et Al 2020 Young Adults Assertiveness in Relation To Parental Acceptance Rejection in GreeceDocument26 pagesMrvoljak Theodoropoulou Et Al 2020 Young Adults Assertiveness in Relation To Parental Acceptance Rejection in GreeceDian HaniNo ratings yet

- Social Psychology AssignmentDocument10 pagesSocial Psychology AssignmentAreeba NoorNo ratings yet

- Terjemahan JURNAL INTERNASIONAL 0 (GRATITUDE IN ADOLESCENT)Document7 pagesTerjemahan JURNAL INTERNASIONAL 0 (GRATITUDE IN ADOLESCENT)Agusmadya Ruza RianaNo ratings yet

- Attachment With Parents and Peers in Late AdolescenceDocument13 pagesAttachment With Parents and Peers in Late AdolescenceLoreca1819No ratings yet

- Literature Review Professional PaperDocument22 pagesLiterature Review Professional PaperAufa CahyaNo ratings yet

- Pjscp2012july 10Document11 pagesPjscp2012july 10MaqboolNo ratings yet

- Young Children's Understanding of Other People's Feelings and Beliefs Individual Differences and Their Antecedents-2Document16 pagesYoung Children's Understanding of Other People's Feelings and Beliefs Individual Differences and Their Antecedents-2SabiqNadzimNo ratings yet

- Dimensions of Conscience in Adolescence PDFDocument13 pagesDimensions of Conscience in Adolescence PDFamara tunisaNo ratings yet

- Personality and Individual Differences: Sarah Galdiolo, Isabelle RoskamDocument8 pagesPersonality and Individual Differences: Sarah Galdiolo, Isabelle RoskamkakonautaNo ratings yet

- The Role of Adult Attachment Style in Forgiveness Following An Interpersonal OffenseDocument10 pagesThe Role of Adult Attachment Style in Forgiveness Following An Interpersonal OffenseEsterNo ratings yet

- Promotion of Empathy and Prosocial Behaviour in CHDocument22 pagesPromotion of Empathy and Prosocial Behaviour in CHMira MiereNo ratings yet

- DevelopmentDocument23 pagesDevelopmentomair.latifNo ratings yet

- Attachment and Emotion in School-Aged Children Borelli Emotion 2010Document11 pagesAttachment and Emotion in School-Aged Children Borelli Emotion 2010LisaDarlingNo ratings yet

- Rice 1996Document8 pagesRice 1996bordian georgeNo ratings yet

- Put Nick 2008Document11 pagesPut Nick 2008Tito AlexandroNo ratings yet

- Emotion Coaching A Universal Strategy FoDocument11 pagesEmotion Coaching A Universal Strategy FoMostafa RamazaniNo ratings yet

- Phương pháp giao tiếp giữa cha mẹ và con cáiDocument13 pagesPhương pháp giao tiếp giữa cha mẹ và con cáitran25235No ratings yet

- hooper2007Document13 pageshooper2007Réka SnakóczkiNo ratings yet

- Fonseca 2020Document9 pagesFonseca 2020Crindle CandyNo ratings yet

- Emotion Reactivity and Regulation in Maltreated Children: A Meta-AnalysisDocument22 pagesEmotion Reactivity and Regulation in Maltreated Children: A Meta-AnalysisRealidades InfinitasNo ratings yet

- Owen Et Al Parental Effects On Compliance 08 2012Document22 pagesOwen Et Al Parental Effects On Compliance 08 2012GOLDFINCHNo ratings yet

- The Voice of Adolescents: Autonomy from Their Point of ViewFrom EverandThe Voice of Adolescents: Autonomy from Their Point of ViewNo ratings yet

- Perdon en NiñosDocument5 pagesPerdon en NiñosCels ZamoranoNo ratings yet

- Peer Attachment and Class Emotional Intelligence As PredictorsDocument9 pagesPeer Attachment and Class Emotional Intelligence As PredictorsNurul HusniNo ratings yet

- Marital Discord of Parents and Its Influence On Adolescents' Self Esteem, Anxiety and Coping Strategies-An Intervention StudyDocument12 pagesMarital Discord of Parents and Its Influence On Adolescents' Self Esteem, Anxiety and Coping Strategies-An Intervention StudyAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- Agreeableness, Extraversion, and Peer Relations in Early Adolescence - Winning Friends and Deflecting Aggression PDFDocument28 pagesAgreeableness, Extraversion, and Peer Relations in Early Adolescence - Winning Friends and Deflecting Aggression PDFSakib BaghoustNo ratings yet

- Exploring Children's Emotional Security As A Mediator Og The Link Between Marital Relations and ChildDocument17 pagesExploring Children's Emotional Security As A Mediator Og The Link Between Marital Relations and ChildNtahpepe LaNo ratings yet

- Mothers' Negative Expressivity Linked to Children's Emotional ExperienceDocument21 pagesMothers' Negative Expressivity Linked to Children's Emotional ExperienceAndreea DanilaNo ratings yet

- Barr Et Al, 2009, How Adolescent Empathy and Prosocial Behavior Change....Document23 pagesBarr Et Al, 2009, How Adolescent Empathy and Prosocial Behavior Change....adrianitanNo ratings yet

- 3-Camisasca (2015)Document13 pages3-Camisasca (2015)Eda ÇolakNo ratings yet

- Shai-Fonagy Parental Embodied MentalizingDocument26 pagesShai-Fonagy Parental Embodied MentalizingCorina IoanaNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Parenting Style and Children's Emotional DevelopmentDocument8 pagesThe Relationship Between Parenting Style and Children's Emotional DevelopmentEdi Hendri MNo ratings yet

- 79-Article Text-654-2-10-20221114Document9 pages79-Article Text-654-2-10-20221114Ellena AyuNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument16 pagesContent ServerMauro GALINDO ESPINOSANo ratings yet

- Ridget Aylor and Annah OCH: Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis Number FallDocument15 pagesRidget Aylor and Annah OCH: Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis Number FallAna-Maria ChiricNo ratings yet

- Joint Attention and Disorganized Attachment Status in Infants at RiskDocument14 pagesJoint Attention and Disorganized Attachment Status in Infants at RiskCarolina Saavedra MellaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal - Attachment Theory and MindfullnessDocument10 pagesJurnal - Attachment Theory and MindfullnessKlinik Psikologi RSBSNo ratings yet

- The Mediational Role: Parenting Sensitivity, Parenta Depression and Child Health: Parental Self-EfficacyDocument14 pagesThe Mediational Role: Parenting Sensitivity, Parenta Depression and Child Health: Parental Self-EfficacyIonela BogdanNo ratings yet

- Socialization and Personality Development: Comment on Vandell (2000Document26 pagesSocialization and Personality Development: Comment on Vandell (2000Joe Sinatra PurbaNo ratings yet

- 8 Handbook of Moral Development (Melanie Killen, Judith G. Smetana) 2023Document11 pages8 Handbook of Moral Development (Melanie Killen, Judith G. Smetana) 2023Isaac Daniel Carrero RoseroNo ratings yet

- Relations between preschoolers' positive empathy and socioemotional functioningDocument12 pagesRelations between preschoolers' positive empathy and socioemotional functioningacelafNo ratings yet

- Parental acceptance impacts adolescent self-esteem and depressionDocument3 pagesParental acceptance impacts adolescent self-esteem and depressionwqewqewrewNo ratings yet

- Accelerating research insightsDocument20 pagesAccelerating research insightsSorina ŞtirNo ratings yet

- Longitudinal Impact of Parental and Adolescent Personality On ParentingDocument12 pagesLongitudinal Impact of Parental and Adolescent Personality On ParentingNidaan KhoviyahNo ratings yet

- Decety2017 PDFDocument12 pagesDecety2017 PDFDUVAN FERNANDO GOMEZ MORALESNo ratings yet

- Counterfactual Thinking and Age Differences in Judgments of Regret and BlameDocument15 pagesCounterfactual Thinking and Age Differences in Judgments of Regret and BlameAnonymous KJBbPI0xeNo ratings yet

- Theory of Mind, Emotion Understanding, Language, and Family Background: Individual Differences and InterrelationsDocument13 pagesTheory of Mind, Emotion Understanding, Language, and Family Background: Individual Differences and InterrelationsHannah Hiu Nam TseNo ratings yet

- Attuned to Others' Positive Emotions? Examining Awareness and ResponsivenessDocument15 pagesAttuned to Others' Positive Emotions? Examining Awareness and ResponsivenessPetrutaNo ratings yet

- Collins and Read, 1990Document20 pagesCollins and Read, 1990Anonymous yjZLqQ100% (1)

- Section V Child Flourishing 14 Childhood Environments and FlourishingDocument24 pagesSection V Child Flourishing 14 Childhood Environments and FlourishingLanie AlabiNo ratings yet

- Preschool Emotional Competence: Pathway To Social Competence?Document19 pagesPreschool Emotional Competence: Pathway To Social Competence?Razel JNo ratings yet

- Baker y Crinic 2007Document17 pagesBaker y Crinic 2007Eduardo GomezNo ratings yet

- Peer AcceptanceDocument15 pagesPeer AcceptanceCoco SSNo ratings yet

- Attachment, Self-Compassion, and Subjective Well-BeingDocument31 pagesAttachment, Self-Compassion, and Subjective Well-BeingBojana VulasNo ratings yet

- Perceived Social Support and Life Satisfaction 1: Department of Psychology 2012Document14 pagesPerceived Social Support and Life Satisfaction 1: Department of Psychology 2012Shumaila Hafeez GhouriNo ratings yet

- Agresivitate Machiavelism EmpatieDocument6 pagesAgresivitate Machiavelism EmpatieIoana AnichitoaieNo ratings yet

- Social-Emotional Development Domain - Child Development (CA DeptDocument18 pagesSocial-Emotional Development Domain - Child Development (CA DeptMia DacuroNo ratings yet

- The DIR Model (Developmental, Individual Difference, Relationship Based) : A Parent Mediated Mental Health Approach To Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument11 pagesThe DIR Model (Developmental, Individual Difference, Relationship Based) : A Parent Mediated Mental Health Approach To Autism Spectrum DisordersLaisy LimeiraNo ratings yet

- Patterns of Interaction - Grotevant & Cooper (1985)Document15 pagesPatterns of Interaction - Grotevant & Cooper (1985)Will ByersNo ratings yet

- Scanned DocumentsDocument1 pageScanned DocumentsWHONo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 CCT-Good Outline (Notes & Examples)Document28 pagesChapter 4 CCT-Good Outline (Notes & Examples)WHONo ratings yet

- Scanned DocumentsDocument1 pageScanned DocumentsWHONo ratings yet

- Adv Functions COPS - Iman and SyairaDocument3 pagesAdv Functions COPS - Iman and SyairaWHONo ratings yet

- Helppppplsss PDFDocument6 pagesHelppppplsss PDFWHONo ratings yet

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument6 pagesScanned With CamscannerWHONo ratings yet

- The Strange and Beautiful Sorrows of Ava Lavender by Leslye Walton - PrologueDocument10 pagesThe Strange and Beautiful Sorrows of Ava Lavender by Leslye Walton - PrologueWalker BooksNo ratings yet

- 527880193-Interchange-2-Teacher-s-Book 2-331Document1 page527880193-Interchange-2-Teacher-s-Book 2-331Luis Fabián Vera NarváezNo ratings yet

- The Eiffel TowerDocument2 pagesThe Eiffel Towerapi-207047212100% (1)

- G3335-90158 MassHunter Offline Installation GCMSDocument19 pagesG3335-90158 MassHunter Offline Installation GCMSlesendreNo ratings yet

- Activity Sheets in Science VIDocument24 pagesActivity Sheets in Science VIFrauddiggerNo ratings yet

- CIMA Financial Accounting Fundamentals Past PapersDocument107 pagesCIMA Financial Accounting Fundamentals Past PapersAnonymous pwAkPZNo ratings yet

- Wireless Local LoopDocument8 pagesWireless Local Loopapi-3827000100% (1)

- Indexed Journals of Pakistan - Medline and EmbaseDocument48 pagesIndexed Journals of Pakistan - Medline and EmbaseFaisal RoohiNo ratings yet

- 07 - Toshkov (2016) Theory in The Research ProcessDocument29 pages07 - Toshkov (2016) Theory in The Research ProcessFerlanda LunaNo ratings yet

- 03 IoT Technical Sales Training Industrial Wireless Deep DiveDocument35 pages03 IoT Technical Sales Training Industrial Wireless Deep Divechindi.comNo ratings yet

- How To Install Elastix On Cloud or VPS EnviornmentDocument4 pagesHow To Install Elastix On Cloud or VPS EnviornmentSammy DomínguezNo ratings yet

- 2023 SPMS Indicators As of MarchDocument22 pages2023 SPMS Indicators As of Marchcds documentNo ratings yet

- Part of Speech QuestionsDocument4 pagesPart of Speech QuestionsNi Luh Ari Kusumawati0% (1)

- 2018 Nissan Qashqai 111809Document512 pages2018 Nissan Qashqai 111809hectorNo ratings yet

- Pre Test in Pe 12Document3 pagesPre Test in Pe 12HERMINIA PANCITONo ratings yet

- Fatima! Through The Eyes of A ChildDocument32 pagesFatima! Through The Eyes of A ChildThe Fatima Center100% (1)

- Members From The Vietnam Food AssociationDocument19 pagesMembers From The Vietnam Food AssociationMaiquynh DoNo ratings yet

- Operational Effectiveness and Strategy - FinalDocument11 pagesOperational Effectiveness and Strategy - FinalChanchal SharmaNo ratings yet

- Marantz sr4200 Service PDFDocument29 pagesMarantz sr4200 Service PDFAnonymous KSedwANo ratings yet

- Bachelor of Agricultural Technology Second Semester Horticulture 1 Pre-TestDocument4 pagesBachelor of Agricultural Technology Second Semester Horticulture 1 Pre-TestBaby G Aldiano Idk100% (1)

- Firebird Developer Guide Beta Delphi FiredacDocument162 pagesFirebird Developer Guide Beta Delphi FiredacDanilo CristianoNo ratings yet

- Calculating parameters for a basic modern transistor amplifierDocument189 pagesCalculating parameters for a basic modern transistor amplifierionioni2000No ratings yet

- Muster Roll 24Document2 pagesMuster Roll 24Admirable AntoNo ratings yet

- Awards and Honors 2018Document79 pagesAwards and Honors 2018rajinder345No ratings yet

- Madhya Pradesh District Connectivity Sector ProjectDocument7 pagesMadhya Pradesh District Connectivity Sector Projectmanish upadhyayNo ratings yet

- Encounters 3Document4 pagesEncounters 3lgwqmsiaNo ratings yet

- Summary and analysis of O. Henry's "The Ransom of Red ChiefDocument1 pageSummary and analysis of O. Henry's "The Ransom of Red ChiefRohan Mehta100% (1)

- Wayside Amenities GuidelinesDocument8 pagesWayside Amenities GuidelinesUbaid UllahNo ratings yet

- Philips NTRX505Document28 pagesPhilips NTRX505EulerMartinsDeMelloNo ratings yet

- Led PowerpointDocument35 pagesLed PowerpointArunkumarNo ratings yet