Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Lecture Notes 104 Module 5

Lecture Notes 104 Module 5

Uploaded by

Camela GinCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Lecture Notes 104 Module 5

Lecture Notes 104 Module 5

Uploaded by

Camela GinCopyright:

Available Formats

Lecture Notes: What Is a Group?

We form self-identities through our communication with others, and much of that interaction occurs in a

group context. A group may be defined as three or more individuals who affiliate, interact or cooperate in a

familial, social, or work context. Group communication1 may be defined as the exchange of information with

those who are alike culturally, linguistically, and/or geographically. Group members may be known by their

symbols, such as patches and insignia on a military uniform. They may be known by their use of specialized

language or jargon; for example, someone in information technology may use the term “server” in reference

to the internet, whereas someone in the food service industry may use “server” to refer to the worker who

takes customer orders in a restaurant. Group members may also be known by their proximity, as in gated

communities. Regardless of how the group defines itself, and regardless of the extent to which its borders are

porous or permeable, a group recognizes itself as a group. Humans naturally make groups a part of their

context or environment.

Types of Groups in the Workplace

As a skilled communicator, learning more about groups, group dynamics, management, and leadership will

serve you well. Mergers, forced sales, downsizing, and entering new markets all call upon individuals within a

business or organization to become members of groups. In our second introductory exercise you were asked

to list the professional (i.e., work-related) groups you interact with in order of frequency. What did your list

include? Perhaps you noted your immediate co-workers, your supervisor and other leaders in your work

situation, members of other departments with whom you communicate, and the colleagues who are also

your personal friends during off-work times. Groups may be defined by function. They can also be defined,

from a developmental viewpoint, by the relationships within them. Groups can also be discussed in terms of

their relationship to the individual, and the degree to which they meet interpersonal

needs.

Some groups may be assembled at work to solve problems, and once the challenge has been resolved, they

dissolve into previous or yet to be determined groups. Functional groups like this may be immediately

familiar to you. You take a class in sociology from a professor of sociology, who is a member of the discipline

of sociology. To be a member of a discipline is to be a disciple, and adhere to a common framework to for

viewing the world. Disciplines involve a common set of theories that explain the world around us, terms to

explain those theories, and have grown to reflect the advance of human knowledge. Compared to your

sociology instructor, your physics instructor may see the world from a completely different perspective. Still,

both may be members of divisions or schools, dedicated to teaching or research, and come together under

the large group heading we know as the university.

In business, we may have marketing experts who are members of the marketing department, who perceive

their tasks differently from a member of the sales staff or someone in accounting. You may work in the

mailroom, and the mailroom staff is a group in itself, both distinct from and interconnected with the larger

organization.

Relationships are part of any group, and can be described in terms of status, power, control, as well as

role, function, or viewpoint. Within a family, for example, the ties that bind you together may be

104 Module 5 Lecture Notes 1|Pag e

common experiences, collaborative efforts, and even pain and suffering. The birth process may forge a

relationship between mother and daughter, but it also may not. An adoption may transform a family.

Relationships are formed through communication interaction across time, and often share a common history,

values, and beliefs about the world around us.

In business, an idea may bring professionals together, and they may even refer to the new product or service

as their “baby,” speaking in reverent tones about a project they have taken from the drawing board and

“birthed” into the real world. As in family communication, work groups or teams may have challenges,

rivalries, and even “birthing pains” as a product is adjusted, adapted, and transformed. Struggles are a part of

relationships, both in families and business, and form a common history of shared challenged overcome

through effort and hard work.

Through conversations and a shared sense that you and your co-workers belong together, you meet many of

your basic human needs, such as the need to feel included, the need for affection, and the need for control.

In a work context, “affection” may sound odd, but we all experience affection at work in the form of friendly

comments like “good morning,” “have a nice weekend,” and “good job!” Our professional lives also fulfill

more basic needs such as air, food, and water, as well as safety. While your workgroup may be gathered

together with common goals, such as to deliver the mail in a timely fashion to the corresponding

departments and individuals, your daily interactions may well go beyond this functional perspective.

In the same way, your family may provide a place for you at the table and meet your basic needs, but they

also may not meet other needs. If you grow to understand yourself and your place in a way that challenges

group norms, you will be able to choose which parts of your life to share and to withhold in different groups,

and to choose where to seek acceptance, affection, and control.

Primary and Secondary Groups

There are fundamentally two types of groups that can be observed in many contexts, from church, to school,

from family to work: primary and secondary groups. The hierarchy denotes the degree to which the group(s)

meet your interpersonal needs. Primary groups meet most, if not all, of one’s needs. Groups that meet some,

but not all, needs are called secondary groups. Secondary groups often include work groups, where the goal

is to complete a task or solve a problem. If you are a member of the sales department, your purpose is to sell.

In terms of problem-solving, work groups can accomplish more than individuals. People, each of whom have

specialized skills, talents, experience, or education come together in new combinations with new challenges,

find new perspectives to create unique approaches that they themselves would not have formulated alone.

Secondary groups may meet your need for professional acceptance, and celebrate your success, but may not

meet your need for understanding and sharing on a personal level. Family members may understand you in

ways that your co-workers cannot, and vice versa.

If Two’s Company and Three’s a Crowd, What Is a Group?

104 Module 5 Lecture Notes 2|Pag e

This old cliché refers to the human tendency to form pairs. Pairing is the most basic form of relationship

formation; it applies to childhood “best friends,” college roommates, romantic couples, business partners,

and many other dyads (two-person relationships). A group, by definition, includes at least three people. We

can categorize groups in terms of their size and complexity.

When we discuss demographic groups as part of a market study, we may focus on large numbers of

individuals that share common characteristics. If you are the producer of an ecologically innovative car such

as the Smart ForTwo, and know your customers have an average of four members in their family, you may

discuss developing a new model with additional seats. While the target audience is a group, car customers

don’t relate to each other as a unified whole. Even if they form car clubs and have regional gatherings, a

newsletter, and competitions at their local race tracks each year, they still subdivide the overall community

of car owners into smaller groups.

The larger the group grows, the more likely it is to subdivide. Analysis of these smaller, or microgroups, is

increasingly a point of study as the internet allows individuals to join people of similar mind or habit to share

across time and distance. A microgroup is a small, independent group that has a link, affiliation, or

association with a larger group. With each additional group member, the number of possible interactions

increases.

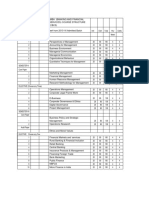

Table 1. Possible Interaction in Groups

Number of Group Members 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Number of Possible Interactions 2 9 28 75 186 441 1,056

Small groups normally contain between three and eight people. One person may involve intrapersonal

communication, while two may constitute interpersonal communication, and both may be present within a

group communication context. You may think to yourself before taking a speech turn or writing your next

post, and you may turn to your neighbor or co-worker and have a side conversation, but a group relationship

normally involves three to eight people.

In Table 1 Possible Interaction in Groups, you can quickly see how the number of possible interactions grows

according to how many people are in the group. At some point, we all find the possible and actual

interactions overwhelming, and subdivide into smaller groups. Forums may have hundreds or thousands of

members, and you may have hundreds of friends on FaceBook, but how many do you regularly communicate

with? You may be tempted to provide a number well north of eight, but if you exclude the “all to one”

messages, such as a general Twitter to everyone (but no one person in particular), you’ll find the group

norms will appear.

Group norms are customs, standards, and behavioral expectations that emerge as a group forms. If you blog

everyday on your FaceBook page, and your friends stop by to post on your wall and comment, and then stop

for a week, you’ll violate a group norm. They will wonder if you are sick or in the hospital where you can’t

access a computer to keep them updated. If, however, you only post once a week, the group will come to

naturally expect your customary post. Norms involve expectations, self and group imposed, that often arise

as groups form and develop.

104 Module 5 Lecture Notes 3|Pag e

If there are more than eight members, it becomes a challenge to have equal participation, where everyone

has a chance to speak, be heard, listen, and respond. Some will dominate, others will recede, and smaller

groups will form. Finding a natural balance within a group can also be a challenge. Small groups need to have

enough members to generate a rich and stimulating exchange of ideas, information, and interaction, but not

so many people that what each brings cannot be shared.

Forming groups fulfills many human needs, such as the need for affiliation, affection, and control; individuals

also need to cooperate in groups to fulfill basic survival needs.

Small Group Communication

Think back to the communication encounters in which you participated yesterday. Chances are you engaged

in a variety of them: eating breakfast with your roommate, exchanging pleasantries with the clerk at the Daily

Grind when you purchased your late-morning coffee, stopping by your favorite professor’s office during her

office hours, presenting a speech in your public-speaking class, spending time with your history study group

preparing for an upcoming project, calling your dad to discuss your weekend trip home, e-mailing your

romantic partner who attends another university, and yelling at the television when your team won in double

overtime. Of these encounters, however, only one can be considered small group communication. Can you

identify which encounter it is?

If you chose the encounter with the study group, you are correct. As you reflect again on these examples, you

will note several characteristics that separate the time spent with the study group from the time spent in the

other encounters. Once you’ve read this lecture notes, the characteristics will become even more apparent.

Before we offer a definition of small group communication, it is important to identify the advantages and

disadvantages of working in a small group. Four advantages are associated with working in a small group. The

first centers on the group’s access to resources, which is considered to be the key advantage to working in

groups. In this sense, resources refer to time; money; member expertise, talent, or ability; or information.

Successful groups take advantage of their access to resources. The second advantage is that group work

provides members with a better understanding and retention of the concepts being examined by the group.

The third advantage is diversity in terms of group member opinion. The fourth advantage is creativity, which

refers to the process by which group members engage in idea generation.

Four disadvantages are associated with working in a group. The first is group member task coordination. As

the number of group members increases, so does the ability for group members to coordinate, monitor, and

regulate how the group task is accomplished. When group size increases, so too does the tendency for group

communication to become less efficient as group members encounter more difficulty managing their

relationships with each other and less communication centers on the group task. The second disadvantage is

social loafing, which refers to the process by which individual member efforts decrease as the number of

group members increases. The larger the group, the greater the likelihood that individual group members will

become more lax in contributing to the group task.

The third disadvantage centers on conflict. Although conflict is inherent in group work, excessive or

destructive fighting and arguing among group members can occur. The fourth disadvantage is coping with

104 Module 5 Lecture Notes 4|Pag e

member misbehaviors. Examples of misbehaviors include missing group meetings, failing to meet deadlines,

spending more time on interpersonal issues than task issues, and failing to respond to member requests.

Although these misbehaviors may be minor, they can become problematic because they affect how the

group eventually completes its task. Additionally, not all members will participate in group interaction. Some

may feel their contributions are not welcomed by other members, some may figure it is easier to let other

group members speak for them, some may feel like they have to fight for the chance to be heard by the

group, or some may be apprehensive about communicating and therefore their contributions (or lack

thereof) are never acknowledged by the group.

Now that you are aware of the advantages and disadvantages of working in a small group, let’s turn our

attention to the definition of small group communication. We define small group communication as three or

more people working interdependently for the purpose of accomplishing a task. To further understand small

group communication, we need to examine the three primary features of small group communication: group

size, interdependence, and task.

Primary Features of Small Group Communication

Group Size

Although small group researchers have disagreed over exactly how many members equate to a group,

the general consensus is that for a small group to exist, it must have a minimum of 3 members and no more

than 15 members. John Cragan and David Wright (1999), two prominent researchers in the field of small

group communication, identified the ideal small group size as five to seven members. Regardless of how

many members a group comprises, it is important to consider that all members have an influence on each

other. This leads us to the next characteristic of a small group, interdependence.

Interdependence

The concept of interdependence is most closely associated with systems theory, which states that all parts of

a system work together to adapt to its environment. Because the parts are linked to one another, a change in

one part affects, in some way, the other parts. The process by which a change in one part affects the other

parts is called interdependence. In a small group, interdependence occurs when members coordinate their

efforts to accomplish their task. When something happens to, or affects, one group member, it will impact

the rest of the group members—that is, interdependence means that any group member’s behavior

influences both group members’ task behaviors and their relational behaviors. Additionally, interdependence

explains why a group can accomplish something collectively that individual members cannot accomplish

alone.

Task

Without a task, a group need not exist. Often considered the purpose behind a group, a task is defined as an

activity in which no externally correct decision exists and whose completion depends on member acceptance.

According to Ira Steiner (1972), small groups face additive tasks and conjunctive tasks. An additive task calls

for group members to work individually on a task or one aspect of a task. Once all group members have

completed their individual tasks, they then combine their efforts to create a final product. Groups that

engage in an additive task often do not demonstrate interdependence until members combine their efforts.

104 Module 5 Lecture Notes 5|Pag e

A conjunctive task requires group members to coordinate their efforts. Rather than work individually, group

members work collectively to create a final product. This case necessitates interdependence from the

moment a task is assigned to the moment of its accomplishment.

Secondary Features of Small Group Communication

Norms

A norm is defined as “the limits of allowable behaviors of individual members of the group”. In other words, a

norm is a guideline or rule designed to regulate the behaviors of group members. Norms can be one of three

types: task, procedural, or social. A task norm enables the group to work toward task accomplishment. For

instance, imagine a volunteer group engaging in brainstorming to select the best way to raise funds for a local

charity. To accomplish this task—selecting the best way to raise funds for a local charity— the group may

establish task norms such as asking members to hold their criticism until all ideas have been generated or

requiring members to provide some support for the idea they are advocating. A procedural norm indicates the

procedures the group will follow. One way the volunteer group can enact a procedural norm is by putting a

time limit on the brainstorming session. A social norm governs how group members engage in interpersonal

communication. Examples of social norms include having the members of the volunteer group address each

other by their first names and going out for coffee after the group meeting.

A group might choose to impose a sanction on a group member if he or she violates a norm. A sanction can be

thought of as a punishment in response to a norm violation. Interestingly, the group also develops sanctions.

For a sanction to be effective, the group must have both the power and the willingness to enforce it. Third,

norms (and the possible accompanying sanctions) usually emerge after the second or third group meeting.

During the first meeting, most group members act on their best behavior because they are either unsure

about the group task or concerned with the impressions they will make on other members. Once group

members reduce their initial uncertainty about the task and each other, they let their guards down

and group norms begin to develop.

Identity

Norms constitute one way a group establishes and maintains its identity. Identity refers to the psychological

and/or physical boundaries that distinguish a group member from a non–group member. Psychological

boundaries refer to the feelings experienced by group members based directly on their group membership.

This psychological identity sometimes is referred to as “we-ness” and can result in both positive and negative

feelings. Positive feelings include pride, cohesion, inclusion, and superiority. Negative feelings include

disappointment, disgust, disapproval, and perhaps even embarrassment. Although these psychological

boundaries are intangible, they play an important role in whether (and how) group members participate in

group tasks, interact with one another, and perceive the group experience as enjoyable and worth their time.

Although the identity shared by group members acts as a powerful influence on them, group identity also can

influence how nonmembers (i.e., people who do not belong to the group) react to group members. This

influence is grouptyping. Grouptyping arises when a nonmember makes assumptions (either positive or

negative) about a person based on the person’s group memberships. These assumptions can be based on any

number of factors: what nonmembers have heard about the group (i.e., the group’s reputation),

nonmembers’ observations of group members, nonmembers’ interactions with one member of the group, or

104 Module 5 Lecture Notes 6|Pag e

the public display of artifacts by any group member. Suppose you decide to go study at the Student Center. As

you scan the food court looking for a place to sit, you notice three available seats: one next to a student

wearing a T-shirt with the letters of a sorority, one next to a student dressed in her ROTC uniform, and one

next to a student wearing a Ben Roethlisberger football jersey. Which seat would you choose? If you made a

judgment (whether positive or negative) about any of these three students based on their public display of

artifacts announcing their group membership, you have engaged in grouptyping.

104 Module 5 Lecture Notes 7|Pag e

You might also like

- Real Communication 4th Edition by Dan Ohair Ebook PDFDocument34 pagesReal Communication 4th Edition by Dan Ohair Ebook PDFsamantha.ryan702100% (48)

- Policy Brief Buller Ogl 350Document8 pagesPolicy Brief Buller Ogl 350api-239499123No ratings yet

- Pragmatic Skills ChecklistDocument4 pagesPragmatic Skills ChecklistLaurell Hagerty100% (1)

- Complete Human Behavior and Victimology ModuleDocument28 pagesComplete Human Behavior and Victimology ModuleCamela Gin87% (15)

- Business Communication For SuccessDocument764 pagesBusiness Communication For Successsilly_rabbitz100% (8)

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Working in GroupsDocument7 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Working in GroupsAnastancius Ariel MacuacuaNo ratings yet

- Personal ReflectionDocument19 pagesPersonal ReflectionVince KechNo ratings yet

- Module 5 - Assignment Crisis International Group CommunicationDocument4 pagesModule 5 - Assignment Crisis International Group CommunicationckelaskarNo ratings yet

- Group Communication: AssignmentDocument5 pagesGroup Communication: AssignmentBINT - e - HAWANo ratings yet

- Group Dynamics CHAPT 9Document9 pagesGroup Dynamics CHAPT 9Odaa BultumNo ratings yet

- Managing DiversityDocument10 pagesManaging DiversityMilica VasilicNo ratings yet

- A Study On Group & Group DynamicsDocument49 pagesA Study On Group & Group Dynamicskairavizanvar100% (1)

- Thesis Group DynamicsDocument4 pagesThesis Group Dynamicsambervoisineanchorage100% (2)

- Thesis Statement On Extracurricular ActivitiesDocument6 pagesThesis Statement On Extracurricular Activitiesnadinebenavidezfortworth100% (2)

- Impact of Mobile Games On Relationships and Interpersonal Skills Among YouthsDocument18 pagesImpact of Mobile Games On Relationships and Interpersonal Skills Among YouthsRenato BenigayNo ratings yet

- Job EmbeddednessDocument6 pagesJob EmbeddednessBaargavi NagarajNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics On Interpersonal CommunicationDocument8 pagesResearch Paper Topics On Interpersonal Communicationcammtpw6100% (1)

- Business Communication For SuccessDocument763 pagesBusiness Communication For SuccessgelunnNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Foundation of Interpersonal and Group BehaviorDocument9 pagesChapter 7 - Foundation of Interpersonal and Group BehaviorThisisfor TiktokNo ratings yet

- Types of GroupsDocument3 pagesTypes of GroupsAli RazaNo ratings yet

- Module 6 Paper Aubrey Joyce 2-20-22Document6 pagesModule 6 Paper Aubrey Joyce 2-20-22api-630173059No ratings yet

- What Is Social CohesionDocument3 pagesWhat Is Social CohesionCharmoli Apum KhrimeNo ratings yet

- Group Dyna-Mix: Investigating team dynamics, from leaders to corporate gatekeepersFrom EverandGroup Dyna-Mix: Investigating team dynamics, from leaders to corporate gatekeepersNo ratings yet

- Project - Group DynamicsDocument45 pagesProject - Group Dynamicsmonzyans100% (1)

- Module 6 11 UtsDocument56 pagesModule 6 11 UtsMilyn DivaNo ratings yet

- Team Advantages Team DisadvantagesDocument7 pagesTeam Advantages Team DisadvantagesAnkitaParabNo ratings yet

- Group Cohesion DissertationDocument4 pagesGroup Cohesion DissertationCustomWritingPaperServiceManchester100% (1)

- Yasir Rahim 19E01014 Answer 1: What Are Interpersonal Skills?Document6 pagesYasir Rahim 19E01014 Answer 1: What Are Interpersonal Skills?Yasir RahimNo ratings yet

- 565 - OBassignment No2Document39 pages565 - OBassignment No2Ambreen SultanNo ratings yet

- Building The Container: Eye ContactDocument13 pagesBuilding The Container: Eye ContactZeyad Omar LardhiNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Conflict Management StylesDocument4 pagesLiterature Review On Conflict Management Stylesafmabhxbudpljr100% (1)

- Reflection 11: Informal and Formal GroupsDocument2 pagesReflection 11: Informal and Formal GroupsMarianNo ratings yet

- Working With GroupsDocument7 pagesWorking With Groupsx483xDNo ratings yet

- Term Paper On Group DynamicsDocument4 pagesTerm Paper On Group Dynamicsafdtywgdu100% (1)

- How Society Is OrganizedDocument2 pagesHow Society Is OrganizedAngily PedrosoNo ratings yet

- Teaching A Methods Course in Social Work With GroupsDocument8 pagesTeaching A Methods Course in Social Work With Groupsf5a1eam9100% (1)

- Modal Verbs ThesisDocument4 pagesModal Verbs Thesisoabfziiig100% (1)

- Life Skill MDocument7 pagesLife Skill MsunilbabaNo ratings yet

- AssertivenessDocument14 pagesAssertivenessJenishBhavsarJoshiNo ratings yet

- Leadership & Teamwork (Essay)Document9 pagesLeadership & Teamwork (Essay)Farrah DiyanaNo ratings yet

- Social: FamilyDocument5 pagesSocial: FamilyNacho TemiñoNo ratings yet

- DLG MGT 244 Human Behavior in OrganizationDocument5 pagesDLG MGT 244 Human Behavior in OrganizationNiña Angeline PazNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society and PoliticsDocument11 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society and PoliticsZeneah MangaliagNo ratings yet

- Communication Theory ChapterDocument13 pagesCommunication Theory ChapterMia SamNo ratings yet

- Group Dynamics Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesGroup Dynamics Research Paper Topicsgw11pm8h100% (1)

- E. How Society Is organized-TIMerDocument12 pagesE. How Society Is organized-TIMerErachne Patulin GloriaNo ratings yet

- What Is A Stakeholder?: Adeel Ahmad BBHM-F19-033Document4 pagesWhat Is A Stakeholder?: Adeel Ahmad BBHM-F19-033Adeel AhmadNo ratings yet

- Organizational BehaviourDocument7 pagesOrganizational Behaviourshahraiz aliNo ratings yet

- Group Dynamics Term PaperDocument7 pagesGroup Dynamics Term Papercuutpmvkg100% (1)

- Social Influence and Group ProcessesDocument7 pagesSocial Influence and Group ProcessesHema KamatNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1: Essence and Importance of Communication: Communication Influences Your Thinking About Yourself and OthersDocument13 pagesLecture 1: Essence and Importance of Communication: Communication Influences Your Thinking About Yourself and Othersgiorgi dvalidzeNo ratings yet

- SolutionDocument4 pagesSolutionBirukNo ratings yet

- The Small GroupDocument17 pagesThe Small GroupDjordje StojanovicNo ratings yet

- Week 7Document2 pagesWeek 7api-640967891No ratings yet

- Example Thesis Statement For Personal Responsibility EssayDocument5 pagesExample Thesis Statement For Personal Responsibility Essaytjgyhvjef100% (1)

- Test1 For People of Poor SightDocument14 pagesTest1 For People of Poor SightDjordje StojanovicNo ratings yet

- Facilitation-Theory and Practice (Complete Module) PDFDocument48 pagesFacilitation-Theory and Practice (Complete Module) PDFJeff Sapitan100% (2)

- Ejusa Nstp1 Midterm Module Leganes Bsba1abcDocument27 pagesEjusa Nstp1 Midterm Module Leganes Bsba1abcma. tricia soberanoNo ratings yet

- Group Structure Learning Outcomes: RolesDocument7 pagesGroup Structure Learning Outcomes: RolesHenrissa Granado TalanNo ratings yet

- Group & Group Dynamics Assignment-HRMDocument18 pagesGroup & Group Dynamics Assignment-HRMsushilyer100% (3)

- Aligned Leadership: Building Relationships, Overcoming Resistance, and Achieving SuccessFrom EverandAligned Leadership: Building Relationships, Overcoming Resistance, and Achieving SuccessNo ratings yet

- Module 3 Global EconomyDocument9 pagesModule 3 Global EconomyCamela GinNo ratings yet

- Identifying Your Communication StyleDocument2 pagesIdentifying Your Communication StyleCamela GinNo ratings yet

- GEC 104 Chapter 1 LNDocument7 pagesGEC 104 Chapter 1 LNCamela GinNo ratings yet

- Mod-14 RIPH 2 20-21Document5 pagesMod-14 RIPH 2 20-21Camela GinNo ratings yet

- 104 Module 6 Lecture NotesDocument8 pages104 Module 6 Lecture NotesCamela GinNo ratings yet

- 104 Chapter 3 Lecture NotesDocument10 pages104 Chapter 3 Lecture NotesCamela GinNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Communication and You An Introduction 1st Edition Mccornack Solutions ManualDocument25 pagesInterpersonal Communication and You An Introduction 1st Edition Mccornack Solutions ManualGuyBoonexfky100% (50)

- Eslbo - Brochure ProjectDocument3 pagesEslbo - Brochure Projectapi-370818279No ratings yet

- Erickson, Rogers, Orem, KingDocument14 pagesErickson, Rogers, Orem, KingaltheaNo ratings yet

- Nursing TheoryDocument5 pagesNursing TheoryPatricia OrtegaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To CommunicationDocument116 pagesIntroduction To CommunicationPreeti Marwah100% (2)

- Overview of Childhood Speech-Language DisordersDocument44 pagesOverview of Childhood Speech-Language DisordersduhneesNo ratings yet

- Midterm On PurCom 1st Sem 20-21Document5 pagesMidterm On PurCom 1st Sem 20-21mascardo franz100% (1)

- Programming (PROG-111) - Grade 11 Week 1-9Document89 pagesProgramming (PROG-111) - Grade 11 Week 1-9chadskie20No ratings yet

- Gen 002 (Sas 1-10)Document13 pagesGen 002 (Sas 1-10)JennieNo ratings yet

- Form 5b Speaking Test RubricsDocument3 pagesForm 5b Speaking Test RubricsJared ValenzuelaNo ratings yet

- COMMUNICATIONDocument17 pagesCOMMUNICATIONVianca Marella SamonteNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Communication and RelationshipsDocument7 pagesInterpersonal Communication and RelationshipsLinh HoangNo ratings yet

- Second Language AcquisitionDocument5 pagesSecond Language AcquisitionCrystal BiruNo ratings yet

- MGT 420 Notes Chapter 1 (Ba240)Document42 pagesMGT 420 Notes Chapter 1 (Ba240)fatinmyNo ratings yet

- Dyadic WrittenDocument8 pagesDyadic WrittenHarrie BirdNo ratings yet

- Functions of Dyadic CommunicationDocument25 pagesFunctions of Dyadic Communicationsurajitbanerji100% (2)

- Communication NegotiationDocument27 pagesCommunication NegotiationdelimakuNo ratings yet

- TCS 1Document83 pagesTCS 1For FunsNo ratings yet

- OralCommSHS q1 Week2 Models of Communication 1 RHEA ANN NAVILLADocument16 pagesOralCommSHS q1 Week2 Models of Communication 1 RHEA ANN NAVILLAJaspher Radoc AbelaNo ratings yet

- DIASSDocument6 pagesDIASSjohnlee rumusudNo ratings yet

- Most Essential Learning Competencies For English Grade 7 To 10Document13 pagesMost Essential Learning Competencies For English Grade 7 To 10Kirby AnaretaNo ratings yet

- Managerial Skill: 1 Alauddin M A WadudDocument35 pagesManagerial Skill: 1 Alauddin M A WadudArmaan AntoNo ratings yet

- Body Language Examples: Category About Us ExploreDocument23 pagesBody Language Examples: Category About Us ExploreAntony JohnNo ratings yet

- MBA BFS CBCS Syllabus and Course Structure 2015 16Document43 pagesMBA BFS CBCS Syllabus and Course Structure 2015 16VarshaNo ratings yet

- Module 5 Light Side of The InternetDocument13 pagesModule 5 Light Side of The InternetJoanne JimenezNo ratings yet

- Revised Receptive Expressive Emergent Language Scale For Kannada Speaking ChildrenDocument29 pagesRevised Receptive Expressive Emergent Language Scale For Kannada Speaking ChildrenJonathan Alexis Salinas UlloaNo ratings yet

- Speech Evaluation Form PDFDocument1 pageSpeech Evaluation Form PDFMuhammad Beni SaputraNo ratings yet

- Term Paper Interpersonal CommunicationDocument4 pagesTerm Paper Interpersonal Communicationafmzsgbmgwtfoh100% (1)