Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Swiffer: Glossary

Uploaded by

Quân Nguyễn0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views1 pageOriginal Title

Ta.P1 (4)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

21 views1 pageThe Swiffer: Glossary

Uploaded by

Quân NguyễnCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

The Swiffer

For a fascinating tale about creativity, look at a cleaning

product called the Swiffer and how it came about, urges

writer Jonah Lehrer. In the story of the Swiffer, he

argues, we have the key elements in producing

breakthrough ideas: frustration, moments of insight

and sheer hard work. The story starts with a

multinational company which had invented products

for keeping homes spotless, and couldn't come up with

better ways to clean floors, so it hired designers to

watch how people cleaned. Frustrated after hundreds of

hours of observation, they one day noticed a woman do

with a paper towel what people do all the time: wipe

something up and throw it away. An idea popped into

lead designer Harry West's head: the solution to their

problem was a floor mop with a disposable cleaning

surface. Mountains of prototypes and years of

teamwork later, they unveiled the Swiffer, which

quickly became a commercial success.

Lehrer, the author of Imagine, a new book that seeks to

explain how creativity works, says this study of the

imagination started from a desire to understand what

happens in the brain at the moment of sudden insight.

'But the book definitely spiraled out of control,' Lehrer

says. 'When you talk to creative people, they'll tell you

about the 'eureka'* moment, but when you press them

they also talk about the hard work that comes

afterwards, so I realised I needed to write about that,

too. And then I realised I couldn't just look at creativity

from the perspective of the brain, because it's also

about the culture and context, about the group and the

team and the way we collaborate.'

When it comes to the mysterious process by which

inspiration comes into your head as if from nowhere,

Lehrer says modern neuroscience has produced a 'first

draft' explanation of what is happening in the brain. He

writes of how burnt-out American singer Bob Dylan

decided to walk away from his musical career in 1965

and escape to a cabin in the woods, only to be overcome

by a desire to write. Apparently 'Like a Rolling Stone'

suddenly flowed from his pen. 'It's like a ghost is

writing a song,' Dylan has reportedly said. 'It gives you

the song and it goes away.' But it's no ghost, according

to Lehrer.

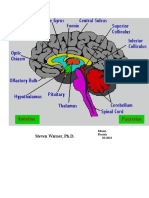

Instead, the right hemisphere of the brain is assembling

connections between past influences and making

something entirely new. Neuroscientists have roughly

charted this process by mapping the brains of people

doing word puzzles solved by making sense of

remotely connecting information. For instance,

subjects are given three words — such as 'age', 'mile'

and 'sand' — and asked to come up with a single word

that can precede or follow each of them to form a

compound word. (It happens to be 'stone'.)

Using brain-imaging equipment, researchers

discovered that when people get the answer in an

apparent flash of insight, a small fold of tissue called

the anterior superior temporal gyrus suddenly lights up

just beforehand. This stays silent when the word puzzle

is solved through careful analysis. Lehrer says that this

area of the brain lights up only after we've hit the wall

on a problem. Then the brain starts hunting through the

'filing cabinets of the right hemisphere' to make the

connections that produce the right answer.

Studies have demonstrated it's possible to predict a

moment of insight up to eight seconds before it arrives.

The predictive signal is a steady rhythm of alpha waves

emanating from the brain's right hemisphere, which are

closely associated with relaxing activities. 'When our

minds are at ease — when those alpha waves are

rippling through the brain — we're more likely to direct

the spotlight of attention towards that stream of remote

associations emanating from the right hemisphere,'

Lehrer writes. 'In contrast, when we are diligently

focused, our attention tends to be towards the details of

the problems we are trying to solve.' In other words,

then we are less likely to make those vital associations.

So, heading out for a walk or lying down are important

phases of the creative process, and smart companies

know this. Some now have a policy of encouraging

staff to take time out during the day and spend time on

things that at first glance are unproductive (like playing

a PC game), but day-dreaming has been shown to be

positively correlated with problem-solving. However,

to be more imaginative, says Lehrer, it's also crucial to

collaborate with people from a wide range of

backgrounds because if colleagues are too socially

intimate, creativity is stifled.

Creativity, it seems, thrives on serendipity. American

entrepreneur Steve Jobs believed so. Lehrer describes

how at Pixar Animation, Jobs designed the entire

workplace to maximise the chance of strangers

bumping into each other, striking up conversations and

learning from one another. He also points to a study of

766 business graduates who had gone on to own their

own companies. Those with the greatest diversity of

acquaintances enjoyed far more success. Lehrer says

he has taken all this on board, and despite his inherent

shyness, when he's sitting next to strangers on a plane

or at a conference, forces himself to initiate

conversations. As for predictions that the rise of the

Internet would make the need for shared working space

obsolete, Lehrer says research shows the opposite has

occurred; when people meet face-to-face, the level of

creativity increases. This is why the kind of place we

live in is so important to innovation. According to

theoretical physicist Geoffrey West, when corporate

institutions get bigger, they often become less receptive

to change. Cities, however, allow our ingenuity to grow

by pulling huge numbers of different people together,

who then exchange ideas. Working from the comfort of

our homes may be convenient, therefore, but it seems

we need the company of others to achieve our finest

'eureka' moments.

Glossary

Eureka: In ancient Greek, the meaning was 'I have

found!'.

Now it can be used when people suddenly find the

solution to a difficult problem and want to celebrate.

You might also like

- Inventology: How We Dream Up Things That Change the WorldFrom EverandInventology: How We Dream Up Things That Change the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Matching Sentence Endings - Practice TasksDocument4 pagesMatching Sentence Endings - Practice Tasksphuong leNo ratings yet

- Chap 6 The Rise of The New GroupthinkDocument5 pagesChap 6 The Rise of The New Groupthinkapi-267185613No ratings yet

- Unlock Your Own CreativityDocument3 pagesUnlock Your Own CreativityNeha Yadav100% (2)

- Jonah Lehrer On How To Be CreativeDocument8 pagesJonah Lehrer On How To Be CreativeGustavo_MazaNo ratings yet

- Synopsis of How The Paper Fish Learned To Swim by Charm SanglayDocument4 pagesSynopsis of How The Paper Fish Learned To Swim by Charm SanglayCharmyne De Vera SanglayNo ratings yet

- Modern Myths of Learning: The Creative Right Brain by Donald H. TaylorDocument4 pagesModern Myths of Learning: The Creative Right Brain by Donald H. TaylorAnt GreenNo ratings yet

- Einsteins Wastebasket Book Done Newest VersionDocument86 pagesEinsteins Wastebasket Book Done Newest Versionandy falconNo ratings yet

- EurekaMoments NYTIMES April2012Document3 pagesEurekaMoments NYTIMES April2012yogimgurtNo ratings yet

- The Science of StorytellingDocument6 pagesThe Science of Storytellingalevill33No ratings yet

- Nine Sapiens: Biology and Evolution of Personality Types: Or how a hunter-gatherer impacted Wall StreetFrom EverandNine Sapiens: Biology and Evolution of Personality Types: Or how a hunter-gatherer impacted Wall StreetNo ratings yet

- Use Stories To Make PointsDocument6 pagesUse Stories To Make PointsthepillquillNo ratings yet

- Week 4Document15 pagesWeek 4Arti RamroopNo ratings yet

- The Origin of Ideas: Blending, Creativity, and The Human SparkDocument312 pagesThe Origin of Ideas: Blending, Creativity, and The Human SparkJorge MoraNo ratings yet

- 95565Document209 pages95565Patrícia VieiraNo ratings yet

- Creative Thinkering: Putting Your Imagination to WorkFrom EverandCreative Thinkering: Putting Your Imagination to WorkRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (10)

- Creating Life: The Art of World Building, #1From EverandCreating Life: The Art of World Building, #1Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Creative Thinkingtoolkit Vol2Document11 pagesCreative Thinkingtoolkit Vol2Muhammad Hamzah SyahrirNo ratings yet

- Reading: A Socio-Historical Perspective: By: Ms. Marites A. Mopera-RohDocument39 pagesReading: A Socio-Historical Perspective: By: Ms. Marites A. Mopera-RohTessNo ratings yet

- Your Brain at Work, Revised and Updated: Strategies for Overcoming Distraction, Regaining Focus, and Working Smarter All Day LongFrom EverandYour Brain at Work, Revised and Updated: Strategies for Overcoming Distraction, Regaining Focus, and Working Smarter All Day LongRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Your Brain at Work: Strategies for Overcoming Distraction, Regaining Focus, and Working Smarter All Day LongFrom EverandYour Brain at Work: Strategies for Overcoming Distraction, Regaining Focus, and Working Smarter All Day LongRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (142)

- 84 Psychology Today March/April 2009: by Josie Glausiusz Photographs by Geof KernDocument8 pages84 Psychology Today March/April 2009: by Josie Glausiusz Photographs by Geof KernbrooklynlouNo ratings yet

- The Real Neuroscience of CreativityDocument6 pagesThe Real Neuroscience of CreativityBook JunkieNo ratings yet

- Programmers GuideDocument372 pagesProgrammers GuideELVIS100% (2)

- Creativity FormulaDocument159 pagesCreativity Formulabackch9011100% (3)

- The Junasiam ThinkingDocument5 pagesThe Junasiam Thinking1iamlegendNo ratings yet

- How To Stimulate Creative BreakthroughsDocument4 pagesHow To Stimulate Creative BreakthroughsVasco HenriquesNo ratings yet

- 25 Books: How To Think & Create, Be Yourself, Communicate, & Learn From OthersDocument27 pages25 Books: How To Think & Create, Be Yourself, Communicate, & Learn From Otherswaseem1986No ratings yet

- Psychological Distance: Larry Dignan Wake Up WorldDocument38 pagesPsychological Distance: Larry Dignan Wake Up WorldThomas TuckerNo ratings yet

- What Is CreativityDocument11 pagesWhat Is Creativitykdon16No ratings yet

- To Change The Way You Think Change The Way You SeeDocument5 pagesTo Change The Way You Think Change The Way You Seebrentjacobs022No ratings yet

- Evolutionary Psychology Primer by Leda Cosmides and John ToobyDocument25 pagesEvolutionary Psychology Primer by Leda Cosmides and John ToobyAnton Dorso100% (1)

- Creativity and The Brain What We Can Learn From Jazz MusiciansDocument4 pagesCreativity and The Brain What We Can Learn From Jazz MusiciansFlavio SilvaNo ratings yet

- Reading Passage 36: A Neuroscientist Reveals How To Think DifferentlyDocument4 pagesReading Passage 36: A Neuroscientist Reveals How To Think DifferentlyJenduekiè DuongNo ratings yet

- Creativity & IntelligenceDocument2 pagesCreativity & IntelligenceAshvin WaghmareNo ratings yet

- Ielts Academic Reading Practice Test 53 67f338b4a6Document4 pagesIelts Academic Reading Practice Test 53 67f338b4a6Sithija WickramaarachchiNo ratings yet

- Creativity Is A ProcessDocument10 pagesCreativity Is A ProcessSubbagren SetpusdokkesNo ratings yet

- Why Read FictionDocument4 pagesWhy Read FictionJuan Pablo OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Mind Essay - Aleksandre AvalishviliDocument4 pagesMind Essay - Aleksandre AvalishviliGuacNo ratings yet

- In Search of A Mechanism - Burton HowardDocument68 pagesIn Search of A Mechanism - Burton HowardStefan Bogdan PavelNo ratings yet

- Learn to Think Using Riddles, Brain Teasers, and Wordplay: Develop a Quick Wit, Think More Creatively and Cleverly, and Train your Problem-Solving instinctsFrom EverandLearn to Think Using Riddles, Brain Teasers, and Wordplay: Develop a Quick Wit, Think More Creatively and Cleverly, and Train your Problem-Solving instinctsNo ratings yet

- Early All Great Ideas Follow A SimilarDocument10 pagesEarly All Great Ideas Follow A SimilarTishan Christopher PrakashNo ratings yet

- Transcription of TED TalksDocument6 pagesTranscription of TED TalksJamela Jade T. BonostroNo ratings yet

- Gapped TextDocument11 pagesGapped TextVy PhạmNo ratings yet

- Dreams ArticleDocument4 pagesDreams ArticleDuezAPNo ratings yet

- (Ion X and TSI) ApocalyptatomanomiconDocument265 pages(Ion X and TSI) ApocalyptatomanomiconExequielRamosNo ratings yet

- Embodied Mind and The Origins of Human CultureDocument19 pagesEmbodied Mind and The Origins of Human CultureMarek AgaNo ratings yet

- A First-Order Approximation To A Neuroscience of Creativity Nov 10 2005Document2 pagesA First-Order Approximation To A Neuroscience of Creativity Nov 10 2005chifteluta1No ratings yet

- De Hoc Sinh Gioi Tieng Anh 11 Nam 2022 2023 Truong THPT Binh Chieu TP HCMDocument8 pagesDe Hoc Sinh Gioi Tieng Anh 11 Nam 2022 2023 Truong THPT Binh Chieu TP HCMQuân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Why Are Finland's Schools Successful?: The Country's Achievements in Education Have Other Nations Doing Their HomeworkDocument1 pageWhy Are Finland's Schools Successful?: The Country's Achievements in Education Have Other Nations Doing Their HomeworkQuân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- BFF1001 Unit Update v3Document5 pagesBFF1001 Unit Update v3Quân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- ECF1100 Zoom Set Up FAQDocument3 pagesECF1100 Zoom Set Up FAQQuân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- The Role of Parents in Preventing Childhood Obesity: Ana C. Lindsay, Katarina M. Sussner, Juhee Kim, and Steven GortmakerDocument18 pagesThe Role of Parents in Preventing Childhood Obesity: Ana C. Lindsay, Katarina M. Sussner, Juhee Kim, and Steven GortmakerQuân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- PP Sat PDFDocument66 pagesPP Sat PDFhafsa mehakNo ratings yet

- Ta P1Document1 pageTa P1Quân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Tackling Hunger in MsekeniDocument1 pageTackling Hunger in MsekeniQuân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Study Guide Listening PDFDocument1 pageStudy Guide Listening PDFGloria JaisonNo ratings yet

- Task 2 International Tourism Script J: Page 1 of 2Document2 pagesTask 2 International Tourism Script J: Page 1 of 2Quân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Task 2 Upbringing Script H: Page 1 of 2Document2 pagesTask 2 Upbringing Script H: Page 1 of 2Quân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Task 2 Upbringing Script H: Page 1 of 2Document2 pagesTask 2 Upbringing Script H: Page 1 of 2Quân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Placebo Effect-The Power of NothingDocument1 pagePlacebo Effect-The Power of NothingQuân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Placebo Effect-The Power of NothingDocument1 pagePlacebo Effect-The Power of NothingQuân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- ANH ĐỀ 1Document3 pagesANH ĐỀ 1Quân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Toan 9 CG 2018 Co Dap AnDocument5 pagesToan 9 CG 2018 Co Dap AnQuân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- ANH ĐỀ 1Document3 pagesANH ĐỀ 1Quân NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Phillips Et Al 2002 Positive MoodDocument11 pagesPhillips Et Al 2002 Positive MoodmechagirlNo ratings yet

- Summary Chart: Holland's Self-Directed Search: RealisticDocument1 pageSummary Chart: Holland's Self-Directed Search: RealisticVanessa KhoNo ratings yet

- 0 Filmstudiesand Media Literacy 20152018Document952 pages0 Filmstudiesand Media Literacy 20152018marnekibNo ratings yet

- Choosing Your Career Skills Questionnaire PDFDocument9 pagesChoosing Your Career Skills Questionnaire PDFJinky RegonayNo ratings yet

- HR's Competency DictionaryDocument27 pagesHR's Competency DictionaryNafizAlam100% (1)

- Anugerah Remaja Perdana Rakan Muda: (The International Award For Young People)Document28 pagesAnugerah Remaja Perdana Rakan Muda: (The International Award For Young People)dinkerekNo ratings yet

- H Sem VI Paper No. BCH 6.3 D New Venture Planning PDFDocument7 pagesH Sem VI Paper No. BCH 6.3 D New Venture Planning PDFSimran100% (1)

- Research On The Development Path of "Yin Yang and Five Elements" Cultural Creative Products Based On Cross-Border E-CommerceDocument7 pagesResearch On The Development Path of "Yin Yang and Five Elements" Cultural Creative Products Based On Cross-Border E-CommercePlayer 7No ratings yet

- Module 5.4 The Global TeacherDocument9 pagesModule 5.4 The Global TeacherLarah Jane MaravilesNo ratings yet

- Creativity and ImaginationDocument21 pagesCreativity and ImaginationSadia KhanNo ratings yet

- Writing Up A Literature Review DR. NGUYEN TRUONG SADocument110 pagesWriting Up A Literature Review DR. NGUYEN TRUONG SAPhương Trần100% (1)

- Sts Cheat Sheet of The BrainDocument30 pagesSts Cheat Sheet of The BrainRahula RakeshNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Gifted ChildrenDocument55 pagesAssessment of Gifted ChildrenMartaLujanesNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Educational Management: Article InformationDocument12 pagesInternational Journal of Educational Management: Article InformationAnys PiNkyNo ratings yet

- Innovation Work PlanDocument4 pagesInnovation Work PlanSteffany Rose TrocioNo ratings yet

- Technopreneurship - Creativity and InnovationDocument68 pagesTechnopreneurship - Creativity and InnovationCamilogs100% (1)

- Intellectual Property and The Creative IndustriesDocument2 pagesIntellectual Property and The Creative IndustriesSteve Maximay100% (1)

- Where Do Great Strategies Come FromDocument10 pagesWhere Do Great Strategies Come Fromdiponogoro100% (1)

- BEUYS, Joseph. 1973 Manifesto PDFDocument2 pagesBEUYS, Joseph. 1973 Manifesto PDFMaíraFernandesdeMeloNo ratings yet

- The New Curriculum For ALSDocument101 pagesThe New Curriculum For ALSGrover DejucosNo ratings yet

- Rubric VideoDocument1 pageRubric VideoRita ArmentanoNo ratings yet

- Activity 1.1 Exploring The School CampusDocument21 pagesActivity 1.1 Exploring The School CampusAj AlagbanNo ratings yet

- Educ6 ReportDocument9 pagesEduc6 ReportBabate AxielvieNo ratings yet

- Practical ResearchDocument2 pagesPractical ResearchAAAAANo ratings yet

- 01 Readings 3Document16 pages01 Readings 3Jun Garry Borja SulapasNo ratings yet

- QSM Tp-ExplanationDocument2 pagesQSM Tp-ExplanationTuri BinignoNo ratings yet

- Negotiation and Conflict ResolutionDocument7 pagesNegotiation and Conflict ResolutionPeterpaul100% (1)

- Careers WorkbookDocument47 pagesCareers WorkbookDr.Varnisikha D NNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in Reading and Writing Grade 11-STEM I. ObjectivesDocument7 pagesLesson Plan in Reading and Writing Grade 11-STEM I. Objectivesjane de leon100% (1)

- DJC 301 Critical ThinkingDocument128 pagesDJC 301 Critical ThinkingCamiloNo ratings yet