0% found this document useful (0 votes)

232 views8 pagesModule 2: Reading and Writing

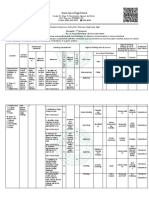

This document provides information about analyzing texts as connected discourses. It discusses how discourses are individual ideas and texts are the sum of connected discourses. A text has characteristics like cohesion, coherence, intentionality, and intertextuality. The document also discusses the importance of making connections between texts and their contexts. It describes critical reading as comprehending ideas, analyzing information, interpreting broader meanings, and critically evaluating arguments. Readers should consider an author's claims and assess whether the evidence and support are strong. Claims can be explicit or implicit and can be of fact or value.

Uploaded by

Zarah CaloCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

232 views8 pagesModule 2: Reading and Writing

This document provides information about analyzing texts as connected discourses. It discusses how discourses are individual ideas and texts are the sum of connected discourses. A text has characteristics like cohesion, coherence, intentionality, and intertextuality. The document also discusses the importance of making connections between texts and their contexts. It describes critical reading as comprehending ideas, analyzing information, interpreting broader meanings, and critically evaluating arguments. Readers should consider an author's claims and assess whether the evidence and support are strong. Claims can be explicit or implicit and can be of fact or value.

Uploaded by

Zarah CaloCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd