Professional Documents

Culture Documents

This Content Downloaded From 176.249.9.200 On Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

Uploaded by

Gabriela M AnișoaraOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

This Content Downloaded From 176.249.9.200 On Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

Uploaded by

Gabriela M AnișoaraCopyright:

Available Formats

TYPES OF TERRORISM BY WORLD SYSTEM LOCATION

Author(s): Omar A. Lizardo and Albert J. Bergesen

Source: Humboldt Journal of Social Relations , 2003, Vol. 27, No. 2 (2003), pp. 162-192

Published by: Department of Sociology, Humboldt State University

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23524157

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Humboldt Journal of

Social Relations

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

162

TYPES OF TERRORISM BY WORLD

SYSTEM LOCATION

Omar A. Lizardo

Albert J. Bergesen

University of Arizona

Abstract: Omar A. Lizardo and Albert J. Bergesen—Graduate Student

and Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of

Arizona—offer a new typology of terrorist activity based on world

system structural location of sub-state groups and state targets. Making

use of this classification, they examine the dynamics of terrorist activity

during the past 130 years by connecting it to larger processes of world

systemic change. A clear pattern emerges from the analysis: during

waves of decolonization and system reorganization, or during periods of

hegemonic supremacy, terrorist activity is contained in either the periphery

or the core structural locations of the system, and its ideological cast is

pragmatic and relatively coherent (national liberation or radical leftist

ideology). The international community typically considers this type of

terrorist activity as internal and "domestic " and within the purview of

the disciplinary forces of the nation states affected. But the systemic

chaos produced by a shift toward a more competitive configuration of

power under conditions of hegemonic decline, produces the "spillover"

and projection of transnational terrorism from the semiperiphery to the

core, in the form of ideologically ill-defined nihilist brands of terror. This

leads toward a rhetorical re-definition of the terrorist threat, from a local

problem to a general affront "against humanity and civilization "as both

the anarchist wave of the 19'h centwy and the Arab-Islamic variant of the

current religious wave have been characterized.

Current research on terrorism1 has focused primarily on issues

of either normative definition or practical prevention. The little

social scientific inquiry that has been directed at the subject has

taken either an essentially reductionist psychological viewpoint,

or has failed to get past the level of the internal group dynamics

and idiographic case studies of isolated organizations (Reich 1990;

Crenshaw 1992; Hoffman 1992). We have recently argued that

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

163

while approaches that focus on the micro to meso-level of social

organization are useful, the study of terrorism will not be furthered

until the level of analysis is ratcheted-up one more level, to that

of the world-system and its reproductive dynamics (Bergesen

and Lizardo 2002a). In this paper we aim to contribute recent

debates on the classification of terrorist activity assuming a wider

theoretical and historical perspective. We attempt to move beyond

extant classificatory attempts by taking into account the larger

international embedding of terrorist organizations and activities

within the structural core/semiperiphery/periphery division of the

world system. After introducing our new typology, we go on to

discuss how the history of modem terrorism ( 1870 to the present)

can be put in the context of recent historical transformations of the

world system. Through this exercise we attempt to demonstrate

that beyond specific local and organizational idiosyncrasies,

modem terrorism—just like other forms of conflict such as war—is

a systemic phenomenon inherently tied to the reproductive dynamics

of capitalism and the interstate system (Bergesen 1985).

A TYPOLOGY OF TERRORISM

Substatal terrorism2 in the modem world-system possesses

two major dimensions of variation: structural location in th

international system, and ideological justification. Structur

location varies along the three-tiered division of the world-syste

into a core, semiperiphery, and a periphery. Thus we may hav

terrorism perpetrated by core actors against core government

organizations (Type-1). We may also observe terrorism th

originates in the periphery or semiperiphery and is directed eith

at other peripheral or semiperipheral governments (Type-2) or

terrorist activity that originates in the periphery or semiperiphery

and is turned against core states (Type-3).3 In terms of the secon

dimension, the ideological variation that has been exhibited by

terrorist groups during their modem history (i.e. since the emergen

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

164

of anarchist terror in the 1870's), it has ranged from anarchic

nihilist, to nationalist-separatist (along racial, ethnic or religious

dimensions), and radical leftist. David Rapoport ( 1999,2001 ) uses

a similar classificatory scheme in order to identify "four waves"

of terrorist activity in the western world since the last third of the

nineteenth century. A first wave of Russian inspired anarchism

(from 1879-1914) swept Europe and the United States and came to

a dramatic end by the beginning of the Second Thirty Years War4

(1914-1945) in Europe, itself sparked by an anarchist assassination.

The second wave ( 1945-1960) consisted of anti-colonial/separatist

terrorist activity in the periphery as African and Asian nationalist

movements rose up against European colonial rule and attacked

their occupants with an assortment of military tactics, including

indiscriminate terror. The third wave (1960-1989) emerged in the

European Core and the Latin American semiperiphery in the form

of radical leftist terrorist groups, and ended with the disintegration

of the Soviet Union in 1989 (Chalk 1999). The fourth wave

subsequently emerged, consisting of—primarily Arab-Islamic—

religiously inspired terrorism (1979 to the present).5 Rapoport

argues that this fourth wave of terror is qualitatively different

from the nationalist-separatist brand of terror practiced by radical

Palestinian groups to this day; its goals seem amorphous and its

justifications—theology and the right to wage holy war—hark back

to the type of religious terrorism, with which the west was familiar

before the rise of modern terror (Rapoport 1984, 1988).

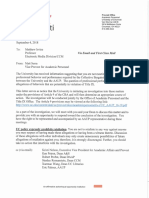

We utilize a modified version of Rapoport's paradigm (See

Figure-1 for a schematic diagram). We agree that the qualitatively

different character of each wave of terrorist activity can be partially

tied to their ideological justification. However, we want to add an

emphasis on the larger international dynamics of the world system,

especially the structural origins and location of the state targets that

each wave of terrorist activity attempts to target. Hence we produce

a two dimensional typology, combining world system location with

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

165

.2 >

D) re

75 5

V) Q}

'E £

55

" re

2 5

"r S

O

z

Figure-1: Waves of Terror in the World-System

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

166

ideological frame (Benford and Snow 2000). Further we dispute

Rapoport's assertion that the current wave of religious terrorist

activity represents a qualitatively different "fourth wave" of modern

terror. Instead, we contend that religiously-inspired terrorism is

simply the return—in holy disguise—of the anarchist-nihilist brand

of terror that swept Europe and the United states during the end of

the 19th century (Hoffman 1995; Joll 1979). We argue that then, as

now, the conditions of the international system foster the appearance

of this type of terrorism. In particular, the disorder and systemic

chaos that was brought about by conditions of then British, today

American hegemonic decline, help to produce the emergence of this

new type of terror (Arrighi and Silver 1999). The fact that anarchic

religious terrorism does not easily fit the received conceptual

structures to which we are accustomed (nationalism, extreme

right or left wing), reflect its direct link to the new world disorder

produced during the transition of the system from its hegemonic

unipolar moment, to a multicentric, competitive condition.

TYPE-1 TERROR: TERROR IN THE CORE

Type-1 terrorism is familiar to students of collective violence in

the West, as it has manifested itself in the form of relatively sudde

popular violence and revolt in core states facing crisis, as during the

world revolutions of 1848 and 1968.6 It has also taken the shap

of more protracted stmggles between smaller, left or right leanin

factions that have specific ideological grievances against particular cor

governments. These groups are usually active for several decades, after

which their resource and support base becomes exhausted, resulting i

either a turn toward less radical action and more traditional forms o

contention—as in the case of the Klan, or a cease fire and comple

dissolution—as happened to the German Red Army and various other

radical leftist terrorist organizations after the revolutions of 1989 tha

swept the communist semiperiphery. The wave of Leftist-Marxi

terrorist activity that inaugurated the postwar resurgence of modem

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

167

terrorism in the core European states after 1968 is the prototypical

example of this kind of terrorist activity (Pluchinsky 1993).

As with all types of terrorist activity, Type-1 terror can assume

one of the three ideological forms discussed above: an ethnic

separatist garb, as with the Basque Struggle in northern Spain

led by the Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA) group; radical leftist

organizations such as the Japanese Red Army, Germany's Red

Army Faction, or the Italian Red Brigades; or an anarchic-nihilist

variant of core origin/core target terror such as the Japan-based

millenarian group Aum Shinrikyo which released a nerve gas attack

on the Tokyo subways in 1995. Type-1 terrorism of either the leftist

radical or ethnic separatist brand is characterized by a high degree

of ideological coherence and militancy. Terrorist groups of this type

have very clear belief systems guiding their actions (whether these

are right or left leaning). Current government structures are seen as

too compromised by multiple contradictory interests to effectively

serve the populace. These organizations thus operate according to

the Gramscian logic of serving or standing for the general interest.

Their primary goal is to garner the type of popular support that will

result in an ultimate take-over of state power. They usually practice

a form of relatively controlled and targeted form of terrorist activity,

choosing their targets carefully in order to maximize their symbolic

value. They prefer to avoid the shock of indiscriminate attacks on the

general populace, directing their violence instead to representatives

of the corrupt state order that they oppose as well as architectural

or private corporate structures. Their activities are stereotyped and

well organized, with routine protocols in terms of issuing warnings,

releasing manifestos, and claiming responsibility.

These core-based radical leftist or ethnic separatist terrorist

organizations are not anti-state per se, but they stand against the

currently dominant state organizations in the core. These are

perceived as too corrupt and uninterested in the welfare of the people

to be of any use. Bruce Hoffman contrasts this type of terrorism

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

168

to the new terrorism (religious anarchic-nihilist) that has become

prominent since the end of the Cold War:

In the past, terrorism was practiced by a group of

individuals belonging to an identifiable organization

with a clear command and control apparatus who had a

defined set of political, social, or economic objectives.

Radical leftist organizations.. .as well as ethno-nationalist

terrorist movements...reflected this stereotype of the

traditional terrorist group. They issued communiqués,

taking credit for—and explaining—their actions and

however disagreeable or distasteful their aims and

motivations were, their ideology and intentions were at

least comprehensible. Most significantly however, these

familiar terrorist groups engaged in highly selective and

mostly discriminate acts of violence. They bombed

various "symbolic" targets representing the source of their

animus (e.g., embassies, banks, national airline carriers) or

kidnapped and assassinated specific persons whom they

blamed for economic exploitation or political repression

generally in order to attract attention to themselves and

their causes (2001,417-418).

Anarchic-nihilist Type-1 terrorists, however, do not share the high

degree of ideological coherence and specificity of targets of the Marxist

and separatist groups7. Their ideologies are usually vague and general,

and they seem to stand for no particular political or social program. This

type of terror has recently been dubbed the new or postmodem terrorism

(Laqueur 1999, 1996). The recent emergence of this type of terror in

core countries however is far from new. Indiscriminate anarchist attacks

swept Europe during the 19lh century, and just like the new postmodem

terrorists, anarchists stood for ill-defined political and social programs.

They seemed to revel in violence and bloodshed for their own sake, and

their degree of coordination and organization was low or non-existent

(Geifman 1993; Joli 1979; Laqueur 1977).

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

169

TYPE-2 TERRORISM:

STRUGGLING AGAINST OPPRESSION

Type-2 terrorism constitutes the bulk of terrorist activity in

the world system. Terrorist groups that arise in the periphery

and semiperiphery and attempt to attack local governments ar

the springboard from which all other forms of modern terrori

group—including Type-1 terrorists—have developed by diffusion

and imitation.

The prototypical modern terrorist group, the Narodnaya Voly

(People's Will), was formed in Russia, a semiperipheral empire, i

the wake of radical struggle against the tsarist regime during the la

third of the 19th century. The emergence of the Narodnaya Vol

stands as a watershed event in the history of modern terrorism

No other organization did more to define and lay down a templa

of how to conduct and organize terrorist activities (Berges

and Lizardo 2002b, Rapoport 2001). Even after its demise, th

People's Will became a model for countless terrorist organization

throughout the world (Joll 1979).

The more popular and media-covered forms of terrorism, s

popularized because they directly affect core states (Type-land

Type-3), represent the tip of the terrorist iceberg in comparison to

Type-2 domestic terrorism in the periphery and semiperipery. T

vast amount of death and destruction occasioned by type-2 terrorist

activity, while vast, is essentially impossible to measure, primari

because it leaves little trace in the form of media coverage or offici

documentation. Suffice to say, that in Turkey one semiperipher

country, over 10,000 people have died from domestic terror, mo

than in all episodes of transnational terrorist activity combine

since the 1960's (Johnson 2001). Type-2 terrorists seldom espous

complex Marxist or Neo-Fascist ideologies.8 These are the terrori

groups around which most researchers of terrorism developed their

frustration and deprivation theories in the 1960's and 1970's (Gu

1970). Their plight is clear, their grievances are straightforwar

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

170

and their targets are oppressive, undemocratic governments that

sustain rule through the ruthless use of state violence.

The peripheral governmental organizations against which Type-2

terrorist groups aim their attacks are usually the leftovers of previous

colonial empires. They are not nation states in the same political mold as

the core states, but protectorates or simply dejure state entities established

by the major powers with little internal legitimacy. Due to this set of

circumstances, most of this type of terrorist activity blends in with the

revolutionary violence of anti-colonial and separatist-emancipatory

movements and their ideology takes the tinge of nationalism and ethnic

recognition in the international community. These goals are usually

either actively or tacitly supported by the rising world power, eager to

secure the destruction of the old hegemon's colonial regime and the

institution of its own neo-colonial order based of expansive rights to

national self-determination.

Type-2 terrorism can occur either at the beginning of the

breakdown of a hegemonic colonial-systemic order or at the end

of one. The initial breakdown phase is a period marked by rising

systemic instability in the semiperiphery, where multiethnic quasi

empires previously supported by the declining world power begin to

splinter. Major powers struggle to gain control by taking advantage

of the instability produced in this zone, a situation that usually leads

to a 30-year conflict known as a major power war.9 After the war,

we enter the end of the breakdown crisis. This is a restructuring

period that is also characterized by instability, this time due to

the shedding of the remnants of the previous order and the laying

down of the infrastructure of the new system by the leading post

war power. If it occurs at the beginning of the hegemonic crisis,

national liberation terrorist activity may be used to demarcate the

area of the international state system that is referred to as a problem

by the principal core states, such as the Prussian principalities in

the 17th century, the Ottoman Empire in the 19lh century, or the

Middle East today.

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

171

Core states usually fight wars of succession and try to control

the interstate system using the disruption produced by Type-2

terrorism in the semiperiphery as an excuse. The event that sparked

the beginning of the Second Thirty Years War, for instance, was

the assassination of the Archduke Francis Ferdinand by a Bosnian

anarchist. Territorial core powers usually view the instability caused

at this kind of terrorism in semiperipheral areas as an opportunity

to extend their zone of influence, while the reigning commercial

sea-power views this kind of meddling by a competing core state

in a sensitive area of the world system as a challenge to its global

dominance. This was the situation between Spain and the Dutch/

French alliance vis a vis the Prussian principalities in the 17th century

and between the British and the German-Austro-Hungarian Alliance

in relation to the Balkans during World War I. Today, American

influence in the Middle East is similarly challenged by attempts on

the part of members of the European Union (especially France) and

the Soviet Union to extend their influence in the area.

After World War II, terrorism arose again, this time harnessed

toward the cause of completing the "liberation" of the ethnic/religious

groups that was initiated in the pre-war phase, but concentrated in

the peripheral areas of the system. In the semiperiphery, the obsolete

protectorate/quasi-imperial structures of domination espoused by

the old hegemon before the war are finally scrapped and replaced

with legally-recognized nation states following the model of the

core states in the system (Bergesen and Lizardo 2002b). Thus,

the Holy Roman Empire did not survive the post Thirty-year war

reconstitution of the European interstate system under the Treaty

of Westphalia, and neither did the Ottoman or Austro-Hungarian

empires survive the onslaught of the Second Thirty Years War of

1914-1945 (Bergesen and Lizardo 2002b). Similarly, the peripheral

Latin American colonies were decolonized after the Napoleonic

Wars and the peripheral African and Asian colonies shared the

same fate at the end of the Second Thirty Years War. Today the

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

172

most internally illegitimate and politically obsolete structures are

the petro-monarchies and autocratic governments of the Middle

East, remnants of the attempts made by U.S. to procure political

stability in the area in the wake of the Cold War struggle for regional

supremacy in the interstate system. This is the area of the world

that has produced not only a large share of type-2 terrorism, but

has also produced the most notable current variant of transnational

(Type-3) terrorist activity in the world system.

Type-2 terrorism does not usually present itself in the anarchic

nihilist ideological mode, but takes either an ethnic-separatist cast

in the prewar phase of destabilization and subsequent breakdown

of the international system, and primarily affects semiperipheral

multiethnic empires and protectorates that gained their support

from the old hegemonic order. In its postwar form, in contrast,

Type-2 terror accompanies the peripheral anti-colonial liberation

movements in line with the system reorganization espoused by the

new world leader.

TYPE-3 TERRORISM:

THE TRANSNATIONAL TURN

Type-3 terrorism is projected from one area of the world system

core/periphery structural division of labor onto another. In terms of

direction, it is perpetrated by groups located in the semiperiphery, bu

is directed at core targets, either at core outposts (military bases or

embassies) throughout the world, core citizens in the semiperiphery,

or civilian and governmental targets and architectural structures in

the core states themselves (Bergesen and Lizardo 2002a). This typ

of terrorist activity is usually referred to as transnational, becau

core elites did not start to notice terrorist activity that crossed state

boundaries until it was exported from semiperipheral states (mostly

the Middle East) toward European core states in the 1960's. This i

what has been dubbed spillover terrorism (Pluchinsky 1987). But the

transnational character of terrorism cuts across all types. As Davi

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

173

Rapoport observes: (2001: 422). "Every [terrorist] wave contains

international ingredients, namely group commitments to international

revolution the willingness of foreign governments and publics to

help, and the sympathies of Diaspora populations."

Thus, there is transnational terrorist activity that is internal

to both the core (Type-1) and the periphery and semiperiphery

(Type-2), and that crosses state boundaries within those structural

divisions (Type-3). One example is the network of leftist terrorist

organizations that flourished in Europe and Latin America during

the 1960'sand 1970's. The transnational character of Type-3 terror

becomes accentuated because it crosses both national and structural

locations. Two waves of Type-three terror have been recorded in

the history of modern terrorism: anarchist terrorism that spread

from Russia at the end of the 19th century and the current wave

of religious terrorism, that began during the last third of the 20th

century (Bergesen and Lizardo 2002a, 2002b). Both waves began

in the semiperiphery (the Russian empire and the Middle East

respectively) and were projected toward Western Europe and the

United States.

Type-3 terror has a long history, probably starting as early as the

conflict between the Sicarii Jewish Zealot group and the Romans

troops occupying ancient Palestine (Rapoport 1984). In its modern

guise, it arises in the last third of the 19th century as an outgrowth of

the anarchist terrorist activity originating in Russia. Major anarchist

figures crossed state lines to either assassinate public figures in

other states, or to orchestrate civilian attacks, primarily in France

by Russian and Italian anarchists:

Between 1894 and 1900 four European heads of states—a

President of France, the Prime Minister of Spain, the

Empress of Austria, and the King of Italy—were

assassinated by professed anarchists. Then, on September

6, 1901, President William McKinley, visiting the Pan

American exposition in Buffalo, was fatally wounded by

Leon Czolgosz, who declared prior to his execution: "I

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

174

don't believe we should have any rulers. It is right to kill

them." But these assaults, committed with daggers and

revolvers, were less unnerving than dynamite attacks on

"bourgeois" cultural and institutional centers. In France

and Spain during the 1890's, bombs were flung into

an opera house, a police station, a church, a mining

company's Paris office, and the Chamber of deputies.

Innocent bystanders, women and children, were blown

to bits. Such episodes justified the used of the term

terrorism. Nothing could be more paralyzing—literally

more full of terror—to the average citizen, far removed

from power, than the fear of death or mutilation at any

moment, in any place, at the hands of an unknown

fanatic. In the United Sates the image of the terrorist

as a whiskered foreigner, holding a round bomb with a

sputtering fuse, became a fixture of cartoonists' repertoires

and the public's onsciousness. After McKinley's death,

President Theodore Roosevelt declared that anarchism

was "a crime against the whole human race" and asked

that the immigration laws be amended to exclude persons

"teaching disbelief in or opposition to...organized

government" (Weisberger 1993).

The recent wave of Arab-Islamic terror has followed a similar

pattern, starting as a purely national liberation variant in Palestine

and domestic grievance-induced terror (Type-2) in other Middle

Eastern countries such as Syria, Saudi-Arabia, and Pakistan. It

began to internationalize with the aid of state sponsors like Libya

in the 1970's and 1980's, and it has recently produced organizations

strictly dedicated to transnational terror such as al Qaeda.

The two major waves of semiperiphery to core terrorist activity

in the modern world system—the anarchist wave of 1870-1914

and the current Arab-Islamic religious wave—have so far been

characterized by their primarily anarchic-nihilist ideological

component. As Niall Ferguson notes:

Since the 1860s, men like the Russian anarchist

Sergei Nechaev had been preaching a doctine of

terrorism in which violence—notionally to further the

revolution— came close to becoming an end in itself.

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

175

It was Nechaev who wrote Principles of Revolution,

which grimly declared, 'We recognize no other activity

but the work of extermination.' As far as his tactics

are concerned, Osama bin Laden owes a bigger debt to

the nineteenth-century Russian nihilists and narodniki

than he does to the CIA...The obvious objection is

that there is a profound difference between pre-1900

nihilism and the Islamic fundamentalism espoused by

bin Laden and his al Qaeda organization. Yet it would

be a grave mistake to overstate the difference. One

of the dangers of Huntington's 'clash of civilizations'

thesis is that it exaggerates the homogeneity of Islam

as a world religion. It might be more illuminating to

regard al Qaeda as the extremist wing of a political

religion.. .That is not to imply, as some writers on the

left have hastened to claim, that al Qaeda, or indeed

the Taliban regime, represents some kind of 'Islamo

fascism'... 'Islamo-nihilism' would be nearer the mark,

or perhaps "Islamo-bolshevism"—for we should not

forget that in their early years Lenin and Stalin were

also terrorists in Nechaevian tradition. Indeed there is

more than a passing resemblance between 'Hereditary

Nobleman Ulyanov' as the young Lenin liked to style

himself, hatching his plans for the overthrow of tsarism

from dingy Swiss hotels, and the renegade Saudi

millionaire orchestrating mayhem from an Afghan

cave (2001: 119-120).

In a similar manner, 19th century anarchist radicals can be

considered the extremist wing of a political movement (leftist

populism) that readily acquired religious and millenarian overtones.

Radical anarchist pamphlets of the time written by major figures such

as Michael Bakunin, Karl Heinzen, and Sergei Nechaev explicitly

mixed in religious themes taken from the Christian apocalyptic

tradition. Some deified the anarchist perpetrator; others sanctified

the cause of cleansing the world from what where perceived as the

evil embodied in government and the ruling classes. In reference

to Bakunin's theory of revolution, Walter Laqueur (1977) writes:

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

176

The revolutionaries, however, should show indifference

toward the lamentations of the doomed, and were not

to enter into any compromise. Their approach might

be called terroristic but this ought not to deter them.

The final aim was to achieve revolution, the cause

of eradicating evil was holy, Russian soil would be

cleansed by sword and fire.

Laqueur adds that the most famous revolutionary document

of the time was written by Bakunin and came to be known as the

"Revolutionary Catechism." In it a mixture of propaganda and

tactical advice is mixed with a theory of revolution that seemed to

sanctify violent struggle (Laqueur 1977). It is not difficult to see

the parallels between Bakunin's dream of cleansing Russian and

European soil from what he deemed the illegitimate usurpers of

power, and Bin Laden's similar claims regarding American bases

in Saudi Arabia desecrating the holly lands of Islam. Rather than

concentrating on the "civilizational" (Huntington 1997) differences

between Arab-Islamic fundamentalism and 19th century anarchist

revolutionary theory, it is more useful to view both as similar

variants of nihilist political religions. If the current wave of Arab

Islamic terror uses religion to cover up its nihilist politics, 19th

century anarchism used nihilist politics to conceal its religious

apocalyptic overtones.

Type-3 terrorist organizations surface out of the failure

and frustration of radical domestic (type-2) terrorism in the

semiperiphery, and therefore their ideology and plans of action

acquire a darker cast. No longer content with the more limited

goal of trying to gain political power in the oppressive local state

from which they appeared, anarchist terrorists shift their attention

toward more general and diffuse targets, including state structures

in the core, which are deemed to be corrupt because of their larger

cultural, political, and military influence and reach. Transnational

anarchists in the 19th century, for example, emerged out of the

violent state response in Russia, Italy, and Spain against anarchist

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

177

organizations tied to left-leaning labor movements. Their demands

and worldview became radicalized to such an extent that they started

to view their mission as one of ridding the world of the oppressive

power of state structures in general. Therefore, their targets become

the more "advanced" (western European and American) states of

the time.

Both 19th century anarchists and the currently active Arab

Islamic terrorist organizations view the secular state model of

the Euro-American core of the world system as an essentially

illegitimate and oppressive institution and therefore do not wish

to redeem it, but simply to further its destruction. To that effect,

they become increasingly indiscriminate in their choice of targets,

and do not practice the type of measured terrorist activity of the

other two types (Laqueur 1999; Hoffman 2001), but rather practice

a kind of "total terror" that can in principle be directed at anyone

that is associated with the putatively oppressive core government

institutions in question. Nineteenth century anarchists were limited

by the low degree of development and availability of objects that

could be turned into weapons of mass destruction, whereas Arab

Islamic anarchic terrorists of today have not only all of the lessons

learned from 130 years of modern terrorism, but also a plethora

of potentially available technological artifacts that can be used to

cause mass casualties (Laqueur 1999). Such was the confluence of

conditions that lead to the attacks on the World Trade Center and

the Pentagon on September 11th.

STRUCTURAL LOCATION, IDEOLOGY, AND

SYSTEMIC TRANSFORMATION

While any type of terror has the potential to acquire any of the

three ideological forms, the history of modern terrorism has shown

more regular patterns, with the emergence of waves of terroris

activities characterized by similar ideological themes concentrate

on particular areas of the world system. The anticolonial wave o

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

178

terrorist activity ( 1945-1960) concentrated in the periphery, and the

leftist radical wave (1960-1979) concentrated in the core European

states. The Anarchist-religious waves (1879-1914 and 1979 to

the present) are distinctive because both start in the semiperiphery

(Russia and the Middle East) and become prevalent in the core at

a later time: France and the United States in the 1890's and all of

western Europe and the United States today (Bergesen and Lizardo

2002a, 2002b). We can thus think of the history of modern terror

as two distinct terrorist waves, one ethnic separatist and the other

Marxist radical, sandwiched between two anarchist-religious

waves (Figure-1). During each, the state of the world system

is going through specific periods of recurrent organization and

restructuring.

During the anticolonial terrorist wave of 1945-1960, the former

colonies of the war-exhausted European powers revolted against

foreign rule. This change was indirectly fostered by the reigning

world power (the U.S.), which was attempting to transform the

system from one based on formal colonialism to one structured

around the ideology of national self-determination and ethnic/

national recognition in the international community. The new

system was undergirded by the emergence of transnational

organizations such as the United Nations, which provide legal

recognition for those states that are able to shake off colonial rule.

Decolonization, of course is synchronized with the expansionary

"A" phase of the world economy underwritten by the rising world

power of the United States (Bergesen and Schoenberg 1980). The

end of the restrictive colonial rule fostered by the defeated European

powers was beneficial for the free trade system instituted by the

United States after the war. The previous system based on formal

colonialism centered in the European core, was in this way replaced

with a neo-colonial system centered in the American core.

The leftist radical wave of terror in the European core (1960

1989) marks the emergence of contemporary terrorism. This

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

179

terrorist wave produces many of the features which are later

adopted by the Arab-Islamic religious wave, such as major state

sponsorship (from the Soviet Union during until 1989) and high

degrees of networking and decentralized organizational structures.10

The international context under which this wave emerges, is of

course, that of the Cold War bipolar world order. But the bipolarity

of the interstate system during this time would turn out to be a

nothing but a mirage. The Soviet Union and its satellite states were

no match for the economic-productive power of the U.S. and its

multinational, vertically-integrated corporations (Arrighi, 1994). It

is no surprise, therefore, that Marxist ideology plays an important

role during this wave, as it is the only ideological system that seems

to be able to stand against the global economic integration and mass

consumption oriented organizational modes of capitalist production

espoused by the United States.

This wave of radical leftist terror is concentrated along those

core states with the closest proximity to the Soviet Union's region

of influence (Germany, Italy, France, and Spain). The terrorist

organizations exemplary of this wave propose coherent plans of

social change and stand against the liberal-democratic consensus

organized by U.S.-lead capitalist expansion. But after the U.S.

led world economic expansion came to an end in the 1970's, the

semiperipheral command economies of the USSR and its satellites

began to encounter serious difficulties.11 Core countries abandoned

the American program of global integration and open markets, and

entered a phase of increased protectionism and bloc formation (e.g.

European integration). Semiperipheral economies, the Soviet Union

included, reacted to the pressure toward change by turning inward

and reforming their autocratic regimes and command economies

(Bergesen 1992a, 1992b). This process led tothe implosion and

disintegration of the Soviet Union. With the demise of the Soviet

Union, the so-called "bipolar" world order also comes to an end.

This development dealt a grave blow to the radical leftist terrorist

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

180

organizations in Europe, which in an amazingly short span of

time (1989-1992), withered away and ultimately disappeared as a

credible threat. The "cease fire" put forth by the most famous and

deadly of these organizations, the German Red Army Faction in

1992, best symbolizes this process which essentially brought the

end of the Marxist terrorist wave (Pluchinsky 1993).

The end of the Soviet Union, therefore, is strictly correlative to

the end of the U.S.-led expansion of the world economy (Bergesen

1992b) and the beginning of American hegemonic decline and loss

of economic dominance (Bergesen and Sonnett, 2000). By 1989,

the United States had already gone from being the world's largest

creditor to the world's largest debtor nation as its Cold War was

predominantly financed with foreign capital (Arrighi and Silver

1999). In addition, the American ability to project global order

had already been seriously deflated by its defeat in the Vietnam

War and alternative productive regimes of capital accumulation

and production that emerged in East Asia, seriously challenged the

economic dominance of the U.S.. Japanese post-war growth had

been unmatched in modem economic history and the "Asian Tigers"

newly industrialized economies along with mainland China, were

beginning to follow suit (Arrighi and Silver 1999). In other words,

the conditions for hegemonic stability had already been seriously

challenged and the system was starting to enter into a multicentric

phase, characterized by rising competition and the decline of the

previous hegemonic center (Arrighi 1994).

The fact that a "new" wave of nihilist religious terror emerges

from the Middle East at about this time, beginning in 1979 and

rising to prominence after 1989 (Enders and Sandler 1999, 2001,

2002), is no coincidence. The international system had found itself

in almost the same conditions under which the Russian anarchist

wave of the 19th century had emerged (Bergesen and Lizardo

2002b). Then the economic, political and military supremacy of

the British complex began to encounter serious challenges. The

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

181

rapidly industrializing German state began to challenge England's

military supremacy in the Europe, while the newly industrializing

United States, a continental nation that dwarfed the British Island

in terms of size and potential productivity, was beginning to exert

its economic and financial muscle. The standard ideological

divisions of Marxist inspired labor movements versus British-led

free trade liberal economic policy had broken down with the defeat

of the workers revolutions of 1848, and the nationalist turn of the

workers movement after a period of growing international class

formation. Similar to the manner in which anarchist radicalism

filled in the ideological vacuum produced by the breakdown of

the liberal regime espoused by Britain in the 19th century, today's

"Islamo-nihilism" (Ferguson 2001) emerges to fill the vacuum left

after the defeat of the communist alternative to American global

capital after 1989 (Barber 1995).

CONCLUDING REMARKS: TERROR AND THE

NATION STATE IN THE WORLD-SYSTEM

This analysis of modern terror aims to show the useful

of a classification of terrorist activity that takes into accoun

structural location and more dynamic system processes. In

above considerations however, one aspect of modern sub

terrorism was purposefully left underdeveloped: its conne

to the rise of the nation state. In fact, terror use by representa

of state power—by Robespierre during the French Revolutio

become the model by which most autocratic states secure

hold over the civilian population (Carr 1996). Insofar as the

pillars of the modern nation state correspond to its monopol

the means of violence and its monopoly over international tr

only substatal entities recognized by the state are able to e

in commerce with representatives of other nation states)1

continuing viability will depend upon securing its hold over

monopolies. Terrorism by challenging one of them (the right of

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

182

state to engage in targeted violence) thus represents a direct affront

to the international order that first developed in Europe after the

First Thirty Years War (1618-1648) with the peace of Westphalia

and that was extended to the rest of the world after U.S.-led post

war decolonization (Arrighi and Silver 1999).

Thus as Wallerstein (1995, 1999), has noted, the socio-political

stability of the modern world system, has rested on the precarious

balance between centrist liberalism, the hierarchical-conservative

right wing and the socialist-egalitarian left wing. The liberal elite in

the core of the world system has, for the most part, been able to bring

both the conservatives and the socialists of the core into collusion,

thus temporarily deferring a major systemic crisis. But radical

anarchism has always been the element that has not had a proper place

in the geo-cultural triad. It is no surprise, therefore, that the protracted

post-1848 crisis in Western Europe and the Ottoman Empire—the last

time that the balance between these three components of the world

system's geo-culture was radically in peril—was characterized by

the emergence of this strand of terrorist political activity. However,

the Bolshevik revolution in the Russian semiperiphery, coupled with

the beginning of the Second Thirty Years War, constituted the two

major developments that helped forestall major systemic crisis. First,

the development of socialism as a powerful political force after 1848

and of state socialism in Russia after 1917, forced the liberal centrist

compromise in the Western European and American core. This came

in the form of the double package of extensive political participation

rights and the welfare state. Second, the beginning of the war gave

a major push to the reactionary forces of nationalism and hierarchy,

thus appeasing the adherents of conservative ideology. To Lenin's

dismay, the socialist political forces in the core were also swept up in

war-induced nationalism, thus consolidating the centrist compromise

between the three components of the geoculture.

After World War I, the United States once again took up the

centrist liberal leadership vacated by a now war-exhausted Great

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

183

Britain and was able to temporarily bring the world-system's geo

culture back into its precarious pre-war balance. But that would be a

short-lived development: the 1968 rejection of the American double

package of mass consumerism in the core and developmentalism

in the semiperiphery, coupled with the turn against the bland

multicultural ideology that replaced radical leftist politics, brought

the world-system's geoculture into its second post-1789 crisis. And

just like the post-1848 crisis, the present one is characterized by

the emergence of anarchic terrorist trends—in the form of religious

fundamentalisms—emerging out the semiperiphery, the fourth

element that seems to appear whenever the liberal-conservative

leftist geocultural balance enters a period of crisis.

As we have seen during waves of decolonization (Bergesen

and Schoeberg 1980) and system restructuring, or during periods of

hegemonic dominance, the threat of terrorism is contained within

the periphery or the core divisions of the system respectively and

its ideological cast is pragmatic and relatively coherent (national

liberation or radical leftist ideology). This type of terrorist

activity can thus be safely classified as internal and "domestic"

and within the purview of the disciplinary forces of the nation

states affected. But the systemic chaos produced by a shift toward

a more competitive multicentric configuration under conditions

of hegemonic decline, produces the "spillover" and projection of

transnational terrorism from the semiperiphery to the core, in the

form of ideologically ill-defined nihilist brands of terror. This leads

toward a rhetorical re-definition of the terrorist threat, from a local

problem to a general affront "against humanity and civilization" as

both the anarchist wave of the 19th century and the current religious

wave have been characterized.

One of the advantages of the above typology is that it explains

why terrorism has been such a difficult phenomenon to identify and

categorize and why there is so little agreement among researchers

and policymakers when it comes to the proper characterization of

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

184

the phenomenon (Crenshaw 1992). Inasmuch as the character of

terrorist activity covaries with the structure of the international

system within which it is embedded, it will present a wide and

sometimes contradictory array of features. Those who think of

terrorists as "rational actors" and "freedom fighters" who choose

to use terror because it is the only available "weapon of the weak"

are taking as their prototype the type of violent terror more likely

to occur during periods of decolonization and system restructuring.

Theories of terrorism and revolution emphasizing deprivation and

autocratic exploitation (Gurr 1970) were developed with this type

of terrorist organization in mind.

In contrast, those who think of terrorists as urban guerrillas,

composed of loose cells with internally differentiated ranks, and

who stand for complex radical ideologies aiming at "changing

the system", take as their model the sort of terrorist activity that

emerged in Europe during the 1960's under the auspices of the Cold

War American hegemonic order. It is hard to apply the paradigm

of exploitation and deprivation consonant with Type-2 terrorists to

this group; after all, this type of terrorism emerges in core states

where liberal democratic freedoms prevail. Many of the theories

of terrorism that emphasized psychology, indoctrination, and the

"terrorist personality" popular during the 1960's and 1970's were a

direct outgrowth of this type of terrorism. Researchers were able to

get close to the subject through interviews and direct observation,

due to the sudden availability of first-world terrorists across the

European landscape.

With the demise of radical terrorists in the core after 1979, a new

breed of theories of terrorism emerge that emphasize the extreme

fanaticism, mass destruction rhetoric, and the "ad hoc" (Chalk

1999), indiscriminate and random character of the new postmodem

terror (Laqueur 1999; Stem 1999; Jurgensmeyer 2000). This shift

is concomitant with the decline of ideologically-motivated Marxist

terrorism and the rise of religious terrorist organizations. But this

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

185

emphasis on the novelty and irrationality of religious terror represents

a theoretical regression, back to 19th century theories of terrorism

which conceived of (anarchist) terror as a senseless phenomenon,

primarily perpetrated by sick and deranged individuals. The

pathologization of terrorism is thus strictly correlative to its religious

nihilist turn in the world system today. But indiscriminate targeting,

dreams of mass destruction, and heroism through suicide are not

a new development in the terrorist imaginary. As the 19th century

anarchist theorist Karl Heinzen proclaimed:

If you have to blow up half a continent and pour

a sea of blood in order to destroy the party of the

barbarians, have no scruples of conscience. He is no

trae republican who would not gladly part with his life

for the satisfaction of exterminating a million barbarians

(as quoted in Laqueur, 1977: 26).

While the anarchist terrorists that put these kind of theories into

practice did engage in indiscriminate acts of terror against civilians

(such as throwing bombs in crowded cafes and other public venues),

they were never able to perpetrate acts of mass destruction. But

this was relative to the technological limitations of the time and not

by a lack of motivation or ideological justification.

Both the anarchist and the current religious waves of terror

have been spurred by rising waves of globalization (in the form of

increasing flows of international trade) and economic integration

in the world system. The first came on the heels of a globalization

wave extending from the 1850's to the 1880's , and the current

wave appears at the peak of third modern wave of globalization—

beginning after 1945, but reaching its highest levels after 1985

(Chase-Dunn, Kawano, and Brewer 2000). Thus, the current

religious-anarchist wave of terrorism interacts with rising degrees

of global integration through telecommunications and transportation

technology. In this sense, the increasing globalization trend has

provided a double boost to religious terrorists. First, the threat

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

186

of homogenization and loss of communal identity becomes one

of the principal motivational catalysts for their action. Second,

the increased technological dependence of most nation states also

facilitates the religious-anarchist terrorist process by providing

them with more opportunities for indiscriminate mass targeting.

As Magnus Ranstorp observes:

As such, the virtual explosion of terrorism in recent

times is part and parcel of a gradual process of what

can be likened to neocolonial liberation straggles. This

process has trapped religious faiths within meaningless

geographical and political boundaries and constraints,

and had been accelerated by grand shifts in the global

political, economic, military and socio-cultural setting,

compounded by difficult local indigenous conditions

for the believers. The uncertainty and unpredictability

of the present environment as the world searches for a

new world order, amidst and increasingly complex global

environment with ethnic and nationalist conflicts, provide

many religious terrorist groups with the opportunity and

the ammunition to shape history according to their divine

duty, cause and mandate while they indicate for others

that the need of time itself is near (1996: 58).

The last wave of anarchist terror became interrupted by the

beginning of the Second Thirty-Years War. This wave of Islamic

religious anarchism may lead the major powers down a similar

path, or in the absence of major power confrontation and alliance

formation, may become along with the other recurrent sources

of system chaos engendered by American hegemonic decline, a

protracted source of instability in the international system.

END NOTES

1 There are numerous types of terrorism occurring in the world and

various attempts at typology and definition of the phenomenon have

already been attempted (Cooper 2001; Ganor 2001; Gibbs 1989; Ruby

2002). Therefore, we will not add to the cacophony here. As a working

definition, we lean on Peter Chalk's conceptualization of terrorism as "the

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

187

systematic use of illegitimate violence that is employed by sub-state actors

as means of achieving specific political objectives, these goals differing

according to the group concerned." (Chalk 1999, p. 151, italics added).

We endorse this definition because it differentiates terrorism by sub-state

actors from state terrorism, which we acknowledge as a phenomenon

of great importance in its own right. However, our focus here is upon

substatal terrorism proper.

2 The term substatal terrorism is used to refer to terrorist activity that

originates from groups of individuals that are not directly connected to

governmental agents and are thus located below the level of the state

as such. While substate terrorists may receive support from external

government agents they remain under our definition as long as they

continue to act on their own interests and not as representatives of some

existing government.

3 A fourth type, terrorist actions that originate with a substatal core agent

that attacks a semiperipheral government, is a residual category that while

not rare, rarely occurs without the support of the core government to

which that substate actor subscribes. Most CIA "intelligence" operations

in weak semiperipheral and peripheral governments that aid and abet

coups and popular revolts against unpopular leaders in Washington, fit

into this category.

4Otherwise known as World Wars I and II.

5 We do not mean to imply that the rise of recent religious terror is an

exclusively Arab-Islamic phenomenon. As has previously been pointed

out (Hoffman, 1995; Ranstorp, 1996), the new holy terror is a general

phenomenon that cuts across religious divides. Thus, there exist Sikh

separatist groups in India and Christian identity cells in the United States.

Further, not all Islamic terror emanates from the Middle East: the Tamil

Tigers of Sri Lanka have become notorious for their relentless use of the

suicide attack method. Middle Eastern Islamic terrorist groups, however,

stand out because they are the most self-consciously transnational of all the

religious terrorist groups, having been able to produce the most audacious

attacks against highly charged symbolic targets of the U.S. international

order, such as military installations, embassies, and the September 11th'

2002 attacks on Washington and the World Trade Center.

6 Contemporary theorizing in world systems analysis postulates that in

addition to localized revolutions at the level of nation states, the modern

world system has experienced two episodes that qualify as world

revolutions, consisting of massive unrest and political crisis in the core.

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

188

These are usually referred to as the revolutions of 1848 and 1968 (see

Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2001, chapter 2 for details), even though the

1848 revolutions did not abate until at least 1865 and the 1968 revolutions

did not culminate until 1989 (Boswell and Chase-Dunn 2001; Arrighi,

Hopkins, and Wallerstein 1992).

7 Type-1 ethnic separatist terrorists, however, may also direct their attacks

at civilians, but these usually belong to different ethnic or religious groups,

as the populist ideology of right-wing terrorists is less inclusive than that

of left-wing terrorists. Right-wing terrorists only extend their populism

to those belonging to their racial, ethnic or religious group and therefore

everybody else may become fair game. In that sense, 1 terrorists may

exhibit more indiscriminate behavior than left leaning Type-lgroups (as

in the Oklahoma City bombings).

8 The Marxist terrorist groups that spread all across the periphery and

semiperiphery of the world system during the post-colonial wave of

leftist terror, represented simply the surface manifestation of Type-2

terrorism during the Cold War. While receiving intensive coverage from

the Western press, semiperipheral terrorist groups with Marxist leanings

never represented more than a new wave of peasant unrest across the

underdeveloped world. Most major terrorist activity in the periphery

and semiperiphery has actually been composed of separatist ethnic and

proto-nationalist movements, such as Turkish PKK (Kurdish Workers

Party), the radical Sikh factions in India, or the Tamil Tigers of Sri Lanka.

The fact that most Marxist groups in the Latin American semiperiphery

were composed of self-consciously identified indigenous groups fighting

for particular rights, precluded unification between them and the more

ideologically motivated core Marxist terrorist organizations in Europe,

which was by an d large a middle class radical movement. When speaking

of Type-1 core terror, therefore, we refer to those groups located in Europe

and not to the indigenous identity peasants movements that emerged in

the periphery in a Marxist garb.

9 The three major examples of this type of conflict in the European interstate

system are the First Thirty Years War (1618-1648), the Napoleonic Wars

(1789-1815), and the Second Thirty Years War (1914-1945), otherwise

known as World War I and II (Boswell and Chase-Dunn, 2001).

10 State sponsorship may have been present during the anarchist terror

wave of the 19"1 century especially, those terrorist organizations operating

in the Balkans (such as the Serbian Black Hand) against Ottoman rule that

were supported by Czarist Russia.

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

189

11 This is evidence against the alleged bipolarity of the world at that time.

Since the Socialist command economies were always part of the larger

capitalist world system, once the Western economies encountered trouble,

the socialist countries followed in their wake, making the post-1970's

economic crisis a truly global one (Frank 1977, 1998).

12 Pirates are the primary substatal agents that have challenged this

monopoly during the modern history of the capitalist world economy.

Semi-feudal drug lords operating in areas of Colombia outside of

government control, are a close contemporary approximation of the pirates

of yesteryear. Piracy was done away with after the British assumed full

hegemony at the beginning of the 19th century. The British used their

superior naval power to destroy any ability of pirates to freely function,

thus freeing the seas from any trade disruption. The current U.S.-led

international "war on drugs" has had less effective results today. The

reason that pirates and drug lords have drawn such a strong and costly

response on the parts of state agents has to be imputed not to some inherent

evil in their activity—after all the British used "piracy" in order to break

down the Chinese imperial ban on the import of opium—but simply to

their direct challenge to the state monopoly on international trade.

REFERENCES

Arrighi, Giovanni. 1994. The Long Twentieth Century: Money, Pow

and the Origins of our Time. New York: Verso.

Arrighi, Giovanni and Beverly J. Silver. 1999. Chaos and Governan

in the Modern World System. Minneapolis: University of Minnes

Press.

Arrighi, Giovanni, Terence K. Hopkins and Immanuel Wallerstein. 19

"The Continuation of 1968." Review 15, 2: 221-242.

Barber, Benjamin R. 1995. Jihad vs. McWorld. New York : Tim

Books.

Benford, Robert D. and David A. Snow. 2000. "Framing Processes

and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment." Annual

Review of Sociology 26: 611-639.

Bergesen, Albert J. 1992a. "Regime Change in the Semiperiphery:

Democratization in Latin America and the Socialist Bloc."

Sociological Perspectives, 35, 2: 405-413.

. 1992b. "Communism's Collapse: A World-System Explanation."

Journal of Political and Military Sociology 20, 1: 133-151.

1985. "Cycles of War in the Reproduction of the World

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

190

Economy." Pp. 313-331 in Rhythms in Politics and Economics,

edited by William R. Thompson and Paul M. Johnson. New York:

Praeger.

Bergesen, Albert J. and Omar Lizardo. 2002a. "Terrorism and World

System Theory." Pp. 9-23 in Terrorism in the World System

Perspective, edited by Ryszard Stemplowski. Warsaw: The Polish

Institute of International Affairs.

2002b. "Terrorism and Hegemonic Decline." (Forthcoming).

In Hegemonic Declines: Present and Past, edited by Jonathan

Friedman and Christopher Chase-Dunn. Walnut Creek, California:

Alta Mira Press.

Bergesen Albert J. and R. Schoenberg. 1980. "Long Waves of Colonial

Expansion and Contraction, 1415-1969." Pp. 231 - 277 in Studies

of the Modern World System, edited by Albert J. Bergesen. New

York: Academic Press.

Bergesen, Albert J. and John Sonnett. 2000. "The Global 500: Mapping

the World Economy at Century's End" American Behavioral

Scientist 44, 10: 1602-1615.

Carr, Caleb. 1996. "Terrorism as Warfare: The Lessons of Military History"

World Policy Journal, 13,4: 1-12.

Chalk, Peter. 1999. "The Evolving Dynamic of Terrorism in the 1990s."

Australian Institute of International Affairs, 53,2: 151-167.

Terry Boswell and Christopher Chase-Dunn. 2001. The Spiral of

Capitalism and Socialism. Colorado: Lynne Rienner.

Chase-Dunn, Christopher; Yukio Kawano, and Benjamin D. Brewer. 2000.

"Trade Globalization Since 1795: Waves of Integration in the World

System." American Sociological Review 65, 1, Feb.: 77-95.

Cooper, H. H. A. 2001. "Terrorism: The Problem of Definition Revisited,"

American Behavioral Scientist 44, 6: 881-893.

Crenshaw, Martha. 1992. "Current Research On Terrorism: The Academic

Perspective." Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 15,1: 1-11.

Enders, Walter and Todd Sandler. 2002. "Patterns of Transnational

Terrorism, 1970-1999: Alternative Time-Series Estimates"

International Studies Quarterly 46, 2: 145-165.

. 2000. "Is Transnational Terrorism Becoming More Threatening?:

A Time-Series Investigation" Journal of Conflict Resolution, 44, 3:

307-332.

. 1999. "Transnational Terrorism in the Post-Cold War Era"

International Studies Quarterly 43, 1: 145-167.

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

191

Ferguson, Niall. 2001. "Clashing Civilizations or Mad Mullahs: The

United States Between Formal and Informal Empire." In The Age of

Terror: America and The World After September 11, edited by Strobe

Talbott and Nayan Chanda. New York: Basic Books.

Frank, Andre Gunder. 1998. "What Went Wrong in the "Socialist" East?"

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations 24, 1 -2: 171-193.

. 1977. "Long Live Trans-ideological Enterprise: The Socialist

Economies in the Capitalist International Division of Labor." Review

1, 1, summer: 91-140.

Ganor, Boaz. 2001. "Terrorism: No Prohibition Without Definition."

International Policy Institute for Counter-Terrorism:http://

www.ict.org.il/

Geifman, Anna. 1993. Thou Shalt Kill: Revolutionary Terrorism in

Russia, 1894-1917. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Gibbs, Jack P. 1989. "Conceptualization of Terrorism" American

Sociological Review, 54, 3: 329-340.

Gurr, Ted Robert. 1970. Why Men Rebel. Princeton: Princeton University

Press.

Hoffman, Buree. 2001. "Change and Continuity in Terrorism." Studies

in Conflict & Terrorism 24: 417-428.

. 1995. "'Holy Terror': The Implications of Terrorism Motivated

by a Religious Imperative" Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 18,

4: 271-284.

1992. "Current Research On Terrorism And Low-Intensity

Conflict." Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 15,1: 25-38.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1997. The Clash Of Civilizations And The

Remaking Of World Order New York : Simon & Schuster.

Johnson, Larry C. 2001. "The Future ofTerrorism." American Behavioral

Scientist 44,6: 894-913.

Joll, James. 1979. The Anarchists. London : Methuen.

Juergensmeyer, Mark. 2000. Terror In The Mind Of God : The Global Rise

Of Religious Violence. Berkeley : University of California Press.

Laqueur, Walter. 1999. The New Terrorism : Fanaticism And The Arms Of

Mass Destruction. New York: Oxford University Press.

. 1996. "Postmodern Terrorism." Foreign Affairs 75,5:24-37.

. 1977. A History of Terrorism. New York : Little, Brown.

Pluchinsky, Dennis. 1993. "Germany's Red Army Faction: An Obituary."

Studies in Conflict and Terrorism, 16: 135-57.

. 1987. "Middle Eastern Terrorist Activity in Western Europe in

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

192

1985: a Diagnosis and Prognosis" in Contemporary Research on

Terrorism, edited by Paul Wilkinson and A. M. Stewart. Aberdeen :

Aberdeen University Press.

Ranstorp, Magnus. 1996. "Terrorism in the Name of Religion" Journal

Of International Affairs 50, 1: 41-63.

Rapoport, David C. 2001. "The Fourth Wave: September 11th in the

History of Terrorism." Current History, 100: 419-424.

. 1999. "Terrorism." In Encyclopedia of Violence Peace and Conflict,

edited by Lester R. Kurtz and Jennifer E. Turpin. London: Academic

Press.

. 1988. "Messianic Sanctions for Terror." Comparative Politics

20,2: 195-213.

1984. "Fear and Trembling: Terrorism in Three Religious

Traditions." American Political Science Review 78: 658-77.

Reich, Walter. 1990. The Origins Of Terrorism : Psychologies, Ideologies,

Theologies, States Of Mind. New York : Cambridge University

Press.

Ruby, Charles L. 2002. "The Definition of Terrorism." Analyses of Social

Issues and Public Policy. 2,2: 9-14: http://www.asap-spssi.org/

Stern, Jessica. 1999. The Ultimate Terrorists. Cambridge: Harvard

University Press.

Weisberger, Bernard A. 1993. "Terrorism Revisited." American Heritage

44,7: 24-26.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1999. The End of the World As We Know It.

Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. 1995. After Liberalism. New York: New Press.

Humboldt Journal of Social Relations - Volume 27, Number 2

This content downloaded from

176.249.9.200 on Tue, 03 May 2022 13:48:43 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- 10.4324 9780203093467 PreviewpdfDocument27 pages10.4324 9780203093467 PreviewpdfGabriela M AnișoaraNo ratings yet

- 10.4324 9780203016633 PreviewpdfDocument57 pages10.4324 9780203016633 PreviewpdfGabriela M AnișoaraNo ratings yet

- How To Market Cultural SymbolsDocument9 pagesHow To Market Cultural SymbolsGabriela M AnișoaraNo ratings yet

- How To Define Terrorism Author(s) : Joshua Sinai Source: Perspectives On Terrorism, February 2008, Vol. 2, No. 4 (February 2008), Pp. 9-11 Published By: Terrorism Research InitiativeDocument4 pagesHow To Define Terrorism Author(s) : Joshua Sinai Source: Perspectives On Terrorism, February 2008, Vol. 2, No. 4 (February 2008), Pp. 9-11 Published By: Terrorism Research InitiativeGabriela M AnișoaraNo ratings yet

- Limits On Interest Rate Rules in The IS Model: William Kerr and Robert G. KingDocument29 pagesLimits On Interest Rate Rules in The IS Model: William Kerr and Robert G. KingGabriela M AnișoaraNo ratings yet

- Brink Lindsey - The US Antidumping Law Rhetoric Vs RealityDocument31 pagesBrink Lindsey - The US Antidumping Law Rhetoric Vs RealityGabriela M AnișoaraNo ratings yet

- An 20 Economic 20 Analysis 20 of 20 Interest 20 Rate 20 Swaps 20 by 20 Bicksler 20 and 20 ChenDocument13 pagesAn 20 Economic 20 Analysis 20 of 20 Interest 20 Rate 20 Swaps 20 by 20 Bicksler 20 and 20 ChenGabriela M AnișoaraNo ratings yet

- How To Market Cultural SymbolsDocument9 pagesHow To Market Cultural SymbolsGabriela M AnișoaraNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)