Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pediatric Contact Lenses Guide

Uploaded by

Sumon SarkarOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pediatric Contact Lenses Guide

Uploaded by

Sumon SarkarCopyright:

Available Formats

14

Pediatric Contact Lenses

Cleusa Coral-Ghanem and

Jeffrey J. Walline

1. What are the indications for contact lens

fitting in the child?

Children may benefit from contact lens wear for a variety of reasons,

ranging from correction of refractive error to vision therapy. The most

frequent indication for fitting children with contact lenses is the cor-

rection of refractive error. Glasses worn to correct high refractive error

may result in image magnification or minification, peripheral distor-

tion, prismatic distortion, and a reduced field of view. The spectacles

worn to correct high refractive error may also be uncomfortable and

cosmetically unappealing, and children can easily remove spectacles

that are uncomfortable, unappealing, or provide poor vision. Contact

lenses may decrease many of the symptoms suffered by children who

wear spectacles for high refractive error, and they are more difficult for

young children to remove.

The purpose of contact lens wear in young children is generally to

optimize visual input so that the child does not develop amblyopia,

but contact lenses may also be fitted to improve the child’s appearance

or to enhance amblyopia therapy routines. Disfigured eyes or unap-

pealing spectacles may be very traumatic for a young child, so contact

lenses may be used to mask disfigured eyes.

Contact lenses may also be used to decrease the amount of light that

reaches the retina in photophobic children, to patch an eye for children

who do not like to wear adhesive patches for amblyopia therapy, or to

decrease the magnitude of nystagmus, thereby improving the vision

and the appearance of children who exhibit nystagmus.

2. Is there a difference between

the fitting of contact lenses in a

child compared to an adult?

A child’s eye is adult sized by 2 years of age. Few contact lenses are

manufactured to fit children’s eyes, specifically so much of the fitting

14. Pediatric Contact Lenses 131

process is similar to adults. The primary challenge in fitting a child is

not due to physical differences. The most difficult aspects of fitting a

child are overcoming the child’s stress, communicating with the child,

and accommodating the rapid development of a young eye.

Despite many similarities between a child’s and an adult’s eye, a

child’s palpebral fissure is generally smaller, which makes it more dif-

ficult to insert and remove contact lenses. This difficulty is exacerbated

when the child is crying. The aqueous component of the tear film is

generally increased in children. Since the concentration of lipids and

proteins in the tears are reduced in children, they rarely have problems

with contact lens deposits, except with contact lenses made of silicone

elastomers, on which lipid deposits may accumulate quickly. The cur-

vature of the cornea decreases over the first 2 years of age from ap-

proximately 45 D to 43 D, and the corneal diameter increases from

approximately 10 mm at birth to 11.5 mm by 3 or 4 years of age.

3. What contact lenses are utilized in

children?

Children can wear rigid gas permeable contact lenses or soft contact

lenses. The indication for contact lens wear and the parents’ experience

with contact lenses should be considered when determining the most

appropriate type of contact lens.

Soft contact lenses are most commonly fitted in children. Parents are

more likely to have experience with soft contact lenses than with rigid

contact lenses, and soft contact lenses may be prescribed in a frequent

replacement program so that spare lenses are readily available. How-

ever, it is difficult to find soft contact lenses with pediatric parameters.

They require more dexterity in handling than rigid gas permeable con-

tact lenses, and they pose a greater risk of infection than rigid contact

lenses, especially with extended wear.

Rigid gas permeable contact lenses are frequently well tolerated by

children, and they are more practical in terms of maintenance and care.

These lenses have excellent oxygen permeability, they correct irregular

astigmatism, and they can be custom made to fit children’s eyes. How-

ever, rigid contact lenses may be less comfortable initially, they are

more likely to dislocate or be lost than soft contact lenses, and they are

not available in multipacks.

4. How does one fit the child?

Some professionals use general anesthesia to fit a contact lens in an

infant. This will certainly facilitate the measurement of the ocular pa-

rameters, refractive power, and evaluation of the contact lens on the

eye, but there are serious potential risks associated with general anes-

thesia. Contact lens fitting under general anesthesia should be re-

stricted to those children who are impossible to examine and fit appro-

priately in the office. When fitting the contact lenses in the operating

room, the main priority is to determine the appropriate power of the

132 C. Coral-Ghanem and J.J. Walline

contact lens. The best method to determine the power is to place a

contact lens on the eye that approximates the resulting refractive error

of the child (approximately Ⳮ35 D). Retinoscopy should be performed

over this contact lens using refractive trial lenses to determine the most

appropriate power. Placing a high plus contact lens on the eye reduces

the error potentially induced by the variable working distance of a high

plus refractive trial lens. It may be necessary to stand on a stool or a

short ladder in order to achieve the appropriate working distance for

a child lying on an operating room table.

A toddler fitted in the office may need to be restrained, which can

be accomplished by having the parent hold the child, by wrapping a

sheet around the child, or by straddling the child while he or she is

lying on the floor. At least one extra pair of hands is necessary to con-

duct the fitting.

An eye care practitioner may consider having an office assistant in-

sert the contact lens in the child’s eye. Children may not trust the person

who inserts the first contact lens for some time thereafter, so evaluation

of the contact lens prescription may become very difficult. Once the

child calms down, the eye care practitioner should evaluate the pre-

scription and fit of the contact lens.

5. How does one examine the lens–cornea

relationship in a child?

Children 5 years and older can typically be examined using a slit-lamp

biomicroscope with fluorescein and a cobalt blue filter. Small children

may need to sit on their knees and hold the slit lamp ‘‘like a motorcycle’’

in order for them to reach the chin rest and for them to be interested

enough to sit still for 1 to 2 minutes. If a child cannot be examined with

a slit lamp in the office, then a hand-hold Burton lamp with fluorescein

can be used. Portable slit lamps and a direct ophthalmoscope/20 D lens

combination works when other methods are not available.

When evaluating a contact lens fit, the key fitting criteria are similar

to those looked for in the adult. One should check the movement, cen-

tration, and fluorescein pattern of a rigid contact lens, and the move-

ment and centration of a soft contact lens. Determination of whether

the power of the contact lens is appropriate is also necessary in all

contact lens fittings.

6. When should contact lenses be fitted in an

aphakic child, and what is the visual

prognosis?

The developing visual system of an infant requires clear vision in order

to achieve maximum visual potential. As little as 1 to 2 weeks of con-

stant visual deprivation can result in amblyopia. When possible, a con-

tact lens should be fitted immediately after surgery or within 1 week.

Fitting the child with a contact lens while he or she is still on the op-

erating table eliminates the potential need for a second dose of general

14. Pediatric Contact Lenses 133

anesthesia, and it decreases the time until the dispensing of the contact

lens.

Contact lens correction is more important and urgent for a unilateral

aphakic child than a bilateral aphakic child. The aphakic eye requires

high plus correction, which results in image size magnification. The

images of the two eyes are not equal in size, so they cannot be fused.

This can lead to symptoms and poor binocular vision development.

Fitting the unilateral aphake with contact lenses minimizes the image

size difference and allows for proper visual input for both eyes.

With careful monitoring and diligent care, an aphakic child can

achieve excellent visual acuity. The parents must be educated about the

continued care and therapy that is necessary to avoid amblyopia, and the

child must be examined regularly. The longer a child has good vision be-

fore a cataract develops, the better the prognosis. The visual prognosis of

an aphakic child following congenital cataracts is worse than the visual

prognosis of an aphakic child following trauma. The child who experi-

enced ocular trauma is more likely to have had a period of normal visual

development than a child with congenital cataracts.

7. What is the best contact lens for

fitting the aphakic child?

Rigid gas permeable contact lenses for aphakia are available in nearly

any material because they are custom designed for individual patients.

Two soft contact lenses specifically designed for pediatric aphakia are

available (Table 14.1).

8. How should one follow up the

aphakic infant in a contact lens?

An aphakic infant should be examined every week for the first 2

months. If the lens fits well and the health of the eye is maintained,

visits may be reduced to every 2 to 4 weeks for several months. When

the refractive error begins to stabilize (at approximately 6 months of

age), the child may be examined every 3 months. This schedule should

continue until the child enters school. At each visit, the child’s vision

should be evaluated, the fit and power of the contact lens should be

evaluated, and the ocular health should be assessed.

Glaucoma may occur in about 10% of children following cataract

removal; therefore, follow-up examinations should consist of routine

glaucoma checks as well. The child should be dilated every 6 to 12

months to evaluate the eye’s posterior segment.

9. What are the complications encountered in

pediatric contact lenses?

The most commonly encountered ocular complications are deposits,

tight contact lenses, and signs of hypoxia. Children may also encounter

134

C. Coral-Ghanem and J.J. Walline

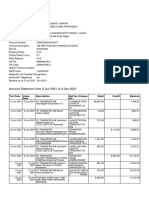

Table 14.1. Soft contact lenses specifically indicated for pediatric aphakia.

Manufacturer Series Material Base curve Diameter Power

Flexlens Products Pediatric Hefilcon A 6.0 to 10.8 mm 10.0 to 16.0 mm ⴐ10.50 to ⴐ30.00 D

(0.3-mm steps) (0.5-mm steps) (0.50-D steps)

Bausch & Lomb Silsoft Super Plus Elastofilcon A 7.5, 7.7, 7.9 11.3 ⴐ23.00 to ⴐ32.00 D

(Pediatric) (3.00-D steps)

14. Pediatric Contact Lenses 135

corneal abrasions and ulcers, but these are more rare. By far, the most

commonly encountered complication is contact lens loss or breakage.

10. What is the social responsibility

of the eye doctor?

In the case of a child with a congenital cataract, if surgery is indicated,

the eye care practitioner must be concerned that the family’s socioeco-

nomic and psychological condition can support the long treatment that

will be necessary. On the other hand, it is possible to create false ex-

pectations and anxiety in the family that has already been assaulted by

the child’s disease. It is necessary that the parents understand the pro-

posed objectives for treatment and the potential benefits and risks. They

must be aware of the duration of the treatment as well as the expenses

that will be incurred. On the other hand, they must also understand

that only their initiative will allow the child to develop better vision.

Selected References

Donzis PB, Weissman BA, Demer JL. Pediatric contact lens care. In: Bennett ES,

Weissman BA, eds. Clinical Contact Lens Practice, Philadelphia: JB Lippincott,

1994: Chapter 51, pp. 1–8.

Matsumoto ER, Murphree L. The use of silicone elastomer lenses in aphakic

pediatric patients. Int Eyecare. 1986; 2:214–217.

Moore B. Managing young children in contact lens. Contact Lens Spectrum. 1996;

34–38.

Pe’er J, Rose L, Cohen E, Benezra D. Hard and soft contact lens fitting in infants.

CLAO J. 1987; 13:46–49.

Stenson SM. Pediatric contact lens fitting. In: Kastl PR, ed. Contact Lenses—The

CLAO Guide to Basic Science and Clinical Practice, Vol 3. Iowa: Kendall/Hunt

Publishing, 1995:179–195.

You might also like

- VisionWithoutGlasses 01 PDFDocument362 pagesVisionWithoutGlasses 01 PDFRenáta Renáta100% (3)

- Teach Yourself Wedding & Event Photography PDFDocument196 pagesTeach Yourself Wedding & Event Photography PDFMatheus BeneditoNo ratings yet

- Guidelines for Prescribing Eyeglasses in Young ChildrenDocument18 pagesGuidelines for Prescribing Eyeglasses in Young Childrenratujelita100% (1)

- 2020VisionWithoutGlasses 02Document23 pages2020VisionWithoutGlasses 02AbduttayyebNo ratings yet

- Energetic Eyehealing - The New Paradigm of Eye Medicine CategoriesDocument6 pagesEnergetic Eyehealing - The New Paradigm of Eye Medicine CategoriesMadon MariaNo ratings yet

- RGP Lens MeasurementDocument5 pagesRGP Lens MeasurementSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- 1 - MyopiaDocument9 pages1 - MyopiaSpislgal PhilipNo ratings yet

- Eyesight And Vision Cure: How To Prevent Eyesight Problems: How To Improve Your Eyesight: Foods, Supplements And Eye Exercises For Better VisionFrom EverandEyesight And Vision Cure: How To Prevent Eyesight Problems: How To Improve Your Eyesight: Foods, Supplements And Eye Exercises For Better VisionNo ratings yet

- Reffractive ErrorsDocument13 pagesReffractive ErrorsSagiraju SrinuNo ratings yet

- Boq Electrical WorksDocument1 pageBoq Electrical WorksreynoldNo ratings yet

- Cycloplegic Retinoscopy in InfancyDocument5 pagesCycloplegic Retinoscopy in InfancyStrauss de LangeNo ratings yet

- Introduction to Optical Emission Spectroscopy (OES) in <40 charsDocument30 pagesIntroduction to Optical Emission Spectroscopy (OES) in <40 charsKleverton JunioNo ratings yet

- (Hybrid Ing A Useful Methdod For FlexographyDocument29 pages(Hybrid Ing A Useful Methdod For FlexographyJose J TharayilNo ratings yet

- Photograph Minimalism StyleDocument15 pagesPhotograph Minimalism StyleAndrei PitigoiNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology With Part 2 (Complete) 2Document59 pagesEpidemiology With Part 2 (Complete) 2nahNo ratings yet

- Optical FiltersDocument18 pagesOptical FiltersGyel TshenNo ratings yet

- EN ISO 3668-2001 - enDocument16 pagesEN ISO 3668-2001 - enJavier Orellana Menacho100% (2)

- Contact Lenses For ChildrenDocument6 pagesContact Lenses For ChildrenmelikebooksNo ratings yet

- BCLA YOUR CHILD & MYOPIA Factsheet FVDocument2 pagesBCLA YOUR CHILD & MYOPIA Factsheet FVJorge CarcacheNo ratings yet

- Congenital Preventable Blindness: of ChildDocument4 pagesCongenital Preventable Blindness: of ChildJustin Michal DassNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Eye Exam Guide for ParentsDocument14 pagesPediatric Eye Exam Guide for ParentsDrSyed Rahil IqbalNo ratings yet

- Myopia ControlDocument3 pagesMyopia ControlEric Chow100% (1)

- Vision Screening1 - CópiaDocument3 pagesVision Screening1 - CópiaRicardo MendesNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Refractive ErrorsDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Refractive Errorsafmzfvlopbchbe100% (1)

- Lazy Eye - NHSDocument1 pageLazy Eye - NHSNikki HooperNo ratings yet

- Optical Correction of Aphakia in Children: Review ArticleDocument12 pagesOptical Correction of Aphakia in Children: Review Articleaisa mutiaraNo ratings yet

- Childhood Cataracts: Aetiology and Management: Indian Supplement Editorial BoardDocument4 pagesChildhood Cataracts: Aetiology and Management: Indian Supplement Editorial Boardnugroho2212No ratings yet

- TimRoot - Chapter 7 - Pediatric OphthalmologyDocument1 pageTimRoot - Chapter 7 - Pediatric OphthalmologyBaeyerNo ratings yet

- Myopia PresentationDocument18 pagesMyopia PresentationEevaeNo ratings yet

- The Pediatric DispenserDocument12 pagesThe Pediatric DispenserTuan DoNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Glaucoma: Advice On Diagnosing and Managing A Rare But Potentially Devastating Group of DiseasesDocument4 pagesPediatric Glaucoma: Advice On Diagnosing and Managing A Rare But Potentially Devastating Group of DiseaseswidyastutiNo ratings yet

- Fact Sheet Congenital Cataracts: Some of The Symptoms of CataractsDocument2 pagesFact Sheet Congenital Cataracts: Some of The Symptoms of CataractsFika SilviaNo ratings yet

- Congenital Cataract: Call 0303 123 9999 Bringing Together People Affected by Sight LossDocument22 pagesCongenital Cataract: Call 0303 123 9999 Bringing Together People Affected by Sight Lossswidy fransinNo ratings yet

- Congenital Cataracts 2019Document22 pagesCongenital Cataracts 2019Evy Alvionita YurnaNo ratings yet

- Accommodative EsotropiaDocument3 pagesAccommodative EsotropiaMedi Sinabutar100% (1)

- Testing Visual Acuity in Children and Non-Verbal AdultsDocument13 pagesTesting Visual Acuity in Children and Non-Verbal AdultsDebi SumarliNo ratings yet

- Eye Exams For ChildrenDocument5 pagesEye Exams For ChildrenDanielz FranceNo ratings yet

- Pediatr Clin Na 2014 Jun 61 (3) 495Document9 pagesPediatr Clin Na 2014 Jun 61 (3) 495mickymed_No ratings yet

- Anisometropia: What is it and how is it treatedDocument2 pagesAnisometropia: What is it and how is it treatedIndhumathiNo ratings yet

- AnisometropiaDocument2 pagesAnisometropiaAstidya MirantiNo ratings yet

- Amblyopia - Diagnosis and Treatment: Pamela J. Kutschke, BS, CoDocument6 pagesAmblyopia - Diagnosis and Treatment: Pamela J. Kutschke, BS, CoKhushbu DedhiaNo ratings yet

- Awareness of Signals of Poor VisionDocument4 pagesAwareness of Signals of Poor VisionmarieNo ratings yet

- Laporan Kasus Lensa Kontak Untuk Bayi - Erie Yuwita SariDocument11 pagesLaporan Kasus Lensa Kontak Untuk Bayi - Erie Yuwita SariSania NadianisaNo ratings yet

- Convergence Insufficiency and Vision TherapyDocument10 pagesConvergence Insufficiency and Vision TherapyMarta GuerreiroNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Strabismus and The Ocular-Motor ExaminationDocument6 pagesIntroduction To Strabismus and The Ocular-Motor ExaminationFitri Aziz AdkNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Population: Anisometropia Treatment OptionsDocument5 pagesPediatric Population: Anisometropia Treatment OptionsmumunooNo ratings yet

- What Is Squint (Strabismus) ?: AmblyopiaDocument2 pagesWhat Is Squint (Strabismus) ?: AmblyopiaAbhinandan SharmaNo ratings yet

- Detecting Squint in KidsDocument5 pagesDetecting Squint in KidsvitriaNo ratings yet

- World Sight Day - 13 October 2022Document2 pagesWorld Sight Day - 13 October 2022Times MediaNo ratings yet

- 2018.12.eye Conditions in Adults - Final 5th December 2018Document18 pages2018.12.eye Conditions in Adults - Final 5th December 2018KOMATSU SHOVELNo ratings yet

- Childhood Squint and Lazy Eye Causes, Symptoms, and TreatmentDocument2 pagesChildhood Squint and Lazy Eye Causes, Symptoms, and TreatmentSrijeeta NagNo ratings yet

- New Rich Text DocumentDocument4 pagesNew Rich Text DocumentAisha TahirNo ratings yet

- Lazy Eye:: Misunderstood Childhood Disorder May Threaten SightDocument2 pagesLazy Eye:: Misunderstood Childhood Disorder May Threaten SightRussell McleodNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Aphakia TreatmentDocument15 pagesPediatric Aphakia TreatmentgaluhanidyaNo ratings yet

- INFOCUS MANUAL CATARACT SCREENINGF Primary-Eye-Care-Manual-Summary1Document21 pagesINFOCUS MANUAL CATARACT SCREENINGF Primary-Eye-Care-Manual-Summary1Si PuputNo ratings yet

- Midterms Pedia Examination of Preschool and School Aged ChildrenDocument49 pagesMidterms Pedia Examination of Preschool and School Aged ChildrenJxce MLeKidNo ratings yet

- 4Document2 pages4Lady TerylleNo ratings yet

- Optometric ManagementDocument4 pagesOptometric ManagementirijoaNo ratings yet

- Amblyopia dan astigmaDocument2 pagesAmblyopia dan astigmaCalistaParamithaNo ratings yet

- 3BP Ojt 1Document23 pages3BP Ojt 1Daniel Anthony CabreraNo ratings yet

- The Paediatric Ophthalmic ExaminationDocument4 pagesThe Paediatric Ophthalmic ExaminationMonly Batari IINo ratings yet

- Causes, Symptoms and Treatment of Squint (StrabismusDocument2 pagesCauses, Symptoms and Treatment of Squint (StrabismusSubhajit BasakNo ratings yet

- Amblyopia eDocument3 pagesAmblyopia eIeien MuthmainnahNo ratings yet

- School Eye Screening and The National Program For Control of Blindness - 2Document6 pagesSchool Eye Screening and The National Program For Control of Blindness - 2rendyjiwonoNo ratings yet

- Clinical OpticDocument43 pagesClinical OpticReinhard TuerahNo ratings yet

- POOR-EYESIGHT BDocument17 pagesPOOR-EYESIGHT Bkenneth mayaoNo ratings yet

- Student Handbook Orthoptics.Document13 pagesStudent Handbook Orthoptics.Nur AminNo ratings yet

- Eye Problems in ChildrenDocument6 pagesEye Problems in ChildrenSachin CharodiNo ratings yet

- 2022-08-27 18 - 53 - 11.578Document1 page2022-08-27 18 - 53 - 11.578Sumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Patient Health HistoryDocument2 pagesPatient Health HistorySumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- 293 FullDocument9 pages293 FullSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Anomalous Retinal Correspondence - Diagnostic Tests and TherapyDocument5 pagesAnomalous Retinal Correspondence - Diagnostic Tests and TherapySumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Silo - Tips - How To Take An Ophthalmic HistoryDocument5 pagesSilo - Tips - How To Take An Ophthalmic HistorySumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Anomalous Retinal Correspondence and Its SignificanceDocument17 pagesAnomalous Retinal Correspondence and Its SignificanceSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- CCLRU contact lens staining scaleDocument2 pagesCCLRU contact lens staining scaleSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- O&A LetterDocument2 pagesO&A LetterSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Umc Meetings 6-6-2022 To 7-6-2022Document4 pagesUmc Meetings 6-6-2022 To 7-6-2022Sumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- BD Community CU (Responses) - Form Responses 1Document1 pageBD Community CU (Responses) - Form Responses 1Sumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Phase 1 Assignment 4Document4 pagesPhase 1 Assignment 4Sumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- SynaptophoreDocument1 pageSynaptophoreSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Answer Key MST 1 OMT 354 CL2Document1 pageAnswer Key MST 1 OMT 354 CL2Sumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Epidemiology in Optometry: Oriahi, M. ODocument4 pagesThe Importance of Epidemiology in Optometry: Oriahi, M. OSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Epidemiological Overview of Preventable Blindness in India-A Focus On Vitamin A Deficiency Among Pre-School Children in IndianDocument20 pagesEpidemiological Overview of Preventable Blindness in India-A Focus On Vitamin A Deficiency Among Pre-School Children in IndianSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- 21UCH-105 21UCH-105: Sr. NoDocument9 pages21UCH-105 21UCH-105: Sr. NoSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Account Statement From 2 Jun 2021 To 2 Dec 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceDocument9 pagesAccount Statement From 2 Jun 2021 To 2 Dec 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3: Units 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3 of Module 2 of The IACLE Contact Lens CourseDocument5 pagesAssignment 3: Units 2.1, 2.2 and 2.3 of Module 2 of The IACLE Contact Lens CourseSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Vision Screening - Dr. WagnerDocument37 pagesVision Screening - Dr. WagnerDien Doan QuangNo ratings yet

- National Programme For Control of Blindness & Visual ImpairmentDocument15 pagesNational Programme For Control of Blindness & Visual ImpairmentSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Account Statement From 1 Nov 2021 To 30 Nov 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceDocument2 pagesAccount Statement From 1 Nov 2021 To 30 Nov 2021: TXN Date Value Date Description Ref No./Cheque No. Debit Credit BalanceSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Aes 03 33Document7 pagesAes 03 33Sumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- EPI-546 Block I Case-Control Studies LectureDocument32 pagesEPI-546 Block I Case-Control Studies LectureSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- National Programme For Control of Blindness: Assistant Prof., Deptt. of Community Medicine GMCH ChandigarhDocument23 pagesNational Programme For Control of Blindness: Assistant Prof., Deptt. of Community Medicine GMCH ChandigarhSumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Semester 4Document15 pagesSemester 4Sumon SarkarNo ratings yet

- Uribapplicationform 67828132Document1 pageUribapplicationform 67828132Jignesh IoharNo ratings yet

- Uribapplicationform 67828132Document1 pageUribapplicationform 67828132Jignesh IoharNo ratings yet

- Bm111 Series: 3KW Auto-Focusing Laser Cutting Heads User ManualDocument29 pagesBm111 Series: 3KW Auto-Focusing Laser Cutting Heads User ManualshrusNo ratings yet

- Elementary Mechanics and Oscillations and Waves Physics LabDocument16 pagesElementary Mechanics and Oscillations and Waves Physics LabAlok ThakkarNo ratings yet

- Visual Faults and Their Correction: by Dhujana NsDocument20 pagesVisual Faults and Their Correction: by Dhujana NsRiniya NajeebNo ratings yet

- 3D OCT 2000series en - BrochureDocument9 pages3D OCT 2000series en - BrochureRodrigo CatalánNo ratings yet

- Crystal Structure Determination: A Crystal Behaves As A 3-D For X-RaysDocument47 pagesCrystal Structure Determination: A Crystal Behaves As A 3-D For X-RaysMadni BhuttaNo ratings yet

- Determination of Effective Permittivity and Permeability of MetamaterialsDocument5 pagesDetermination of Effective Permittivity and Permeability of MetamaterialskhyatichavdaNo ratings yet

- EC 6702 - Questions With Answers - OC New FinalDocument101 pagesEC 6702 - Questions With Answers - OC New FinalSathya PriyaNo ratings yet

- Electrostatics and Electromagnetism Short Answer QuestionsDocument4 pagesElectrostatics and Electromagnetism Short Answer QuestionsRemusNo ratings yet

- Bhagalpur College of Engineering, Bhagalpur: Utilization of Electric PowerDocument26 pagesBhagalpur College of Engineering, Bhagalpur: Utilization of Electric PowerArko GhoshNo ratings yet

- Photonic Crystal Fiber Properties and ApplicationsDocument17 pagesPhotonic Crystal Fiber Properties and ApplicationsAna SimovicNo ratings yet

- AUMcatalogue2007 BigDocument91 pagesAUMcatalogue2007 BigJaimasaNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Visible Surface Detection and Surface-RenderingDocument16 pagesUnit 4 Visible Surface Detection and Surface-RenderingimmNo ratings yet

- Accurate Behavioral Model of Photodiode For CMOS Imagers With Device ParasiticDocument15 pagesAccurate Behavioral Model of Photodiode For CMOS Imagers With Device ParasiticAnas IftikharNo ratings yet

- Cinematography: The Art of Visual StorytellingDocument12 pagesCinematography: The Art of Visual StorytellingharshithNo ratings yet

- Chelsea Mayer Cinematography ResuméDocument7 pagesChelsea Mayer Cinematography ResuméKevin ScottNo ratings yet

- Info Az Barli IIDocument21 pagesInfo Az Barli IIKrzysiek GibasiewiczNo ratings yet

- Laser Safety Document OverviewDocument80 pagesLaser Safety Document OverviewriomjNo ratings yet

- 3D Holographic Projection Technology: Submitted ByDocument22 pages3D Holographic Projection Technology: Submitted BySoham GuptaNo ratings yet

- 07 AstigmatismDocument20 pages07 AstigmatismMwanja MosesNo ratings yet

- Ray Optics PDFDocument36 pagesRay Optics PDFHrishikesh BhatNo ratings yet

- Applied Photometry, Radiometry, and Measurements of Optical LossesDocument6 pagesApplied Photometry, Radiometry, and Measurements of Optical Lossesbitconcepts9781No ratings yet

- Understanding Waves: A Concise GuideDocument13 pagesUnderstanding Waves: A Concise GuideMazni HanisahNo ratings yet

- Key EnceDocument8 pagesKey EnceRafa SánchezNo ratings yet