Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The University of Chicago Press Bard Graduate Center

Uploaded by

Géza HegedűsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The University of Chicago Press Bard Graduate Center

Uploaded by

Géza HegedűsCopyright:

Available Formats

Hungarian Nationalism, Gottfried Semper, and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art

Author(s): Rebecca Houze

Source: Studies in the Decorative Arts, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Spring–Summer 2009), pp. 7-38

Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Bard Graduate Center

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/652503 .

Accessed: 14/03/2014 12:23

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press and Bard Graduate Center are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve

and extend access to Studies in the Decorative Arts.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Hungarian Nationalism, Gottfried Semper, REBECCA HOUZE

and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art

The Iparművészeti Múzeum (Museum of Applied Art) is often under-

stood as one of the most striking examples of Hungarian Art Nouveau

(Fig. 1). Built in 1896 by the architects Ödön Lechner (1845-1914) and

Gyula Pártos (1845-1916) as part of the Millennial Celebrations in

Budapest, the museum was a national monument and an evocative

symbol of Hungary’s new emphasis on the applied arts as a means of

promoting a national culture. Textiles and ceramics were at the center of

the Hungarian applied arts movement at the turn of the nineteenth to

the twentieth century and were seen as the key to integrating Hungary’s

native folk culture with its modern industrial identity. Lechner made his

own interpretation of this larger cultural movement in the building’s

vibrant dress—its cladding of glazed ceramic tiles with colorful patterns

derived from the peasant embroideries of traditional Hungarian folk

costume. Equally important to the conception of the museum were the

theories of the German architect and art historian Gottfried Semper

(1803-1879), who argued that textiles and ceramics were the primordial

fields of art-making and were, furthermore, the precursors to building

itself. Semper’s theories were mirrored in the decision of the Iparmű-

vészeti Múzeum director Ferenc Pulzsky to focus on textiles and ceramics

as the core of the new collections. Lechner’s conception of the museum’s

ornament as a reflection of the evolution of a national Hungarian style

is a crucial link between the museum’s program and its design. The

museum’s ornamentation, planning, and conceptual origins all stemmed

from Semper’s theoretical understanding of the relationship between

textiles and architecture. The museum’s ornate organic ornament is thus

more aptly understood as reflecting the complex intellectual debates over

the meaning and form of Hungarian folk art than the broader and more

purely aesthetic notion of Art Nouveau.

The Museum Building’s Stylistic Sources

As the visitor approaches the Iparművészeti Múzeum today, its

bright green and yellow tiled roof stands out against the busy backdrop of

Rebecca Houze is Associate Professor in the Department of Art History, Northern Illinois

University, DeKalb.

Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009 7

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

Pest, which was rapidly developed in the late nineteenth century with

wide avenues and bourgeois apartment blocks.1 The massive building,

which eventually accommodated both the museum and its affiliated

school, wraps around a trapezoidal city block (Fig. 2). Its asymmetrical

wings, used for storage galleries, archives, and library, embrace the

interior exhibition hall, which is entered from the street by passing

through an extraordinary foyer, decorated in richly colored ceramic tiles

(Figs. 3-4). Most of the building’s surface is covered in buff-colored brick;

its piers and windows are framed in dark gray stone. Yellow ceramic tile

panels, covered with red and green flowers and butterflies, are set spar-

ingly into the façade to emphasize the repeating pattern of the arched

windows (Fig. 5).

Despite its size, the building is not imposing. In its height and the

flatness of its façade the Museum is harmonious with the neighboring

buildings along the Üllői út (avenue), a busy thoroughfare that runs

southeast, away from the Danube and the inner ring of Pest. The

museum, located near the intersection of the Üllői út and the Jozsef körút

(boulevard), lies just outside many of the city’s most notable cultural and

civic buildings of the nineteenth century, including the Opera and

Parliament. The adjacent Kálvin tér (square) was the site of Budapest’s

first horse-drawn streetcars, introduced in 1866. These were replaced

with electric tramlines beginning in 1887, a few years after the grand

Keleti train station to the northeast was completed. With the rise of

modern transportation and heavy factory production in Pest in the late

nineteenth century, the city became a dense and increasingly congested

modern space. Until the late 1890s, Budapest architects tended to favor

romantic Gothic revivals with exotic references, as well as Neo-Renais-

sance designs. By the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century

many had adopted Art Nouveau, which was popularized in modern

applied arts journals and international exhibitions abroad. The more

innovative stylistic elements of the Iparművészeti Múzeum have been

traditionally attributed to Lechner, who was a strong supporter of the

new movement in both his writings and buildings after 1896, when he

and Pártos dissolved their partnership. The design for the new Iparmű-

vészeti Múzeum represents a transitional style that began to break away

from many architectural conventions of the period. It responded in a

sophisticated fashion to the complex urban fabric of Pest, with its

eclectic range of building styles and particular social and cultural needs.

The exterior tiles for the new museum were produced by the Zsolnay

Company, which had gained international celebrity in the second half of

the nineteenth century for its decorative porcelain ware and fireproof

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 9

pyrogranite—architectural ceramics used throughout Hungary for build- FIGURE 1

ing rooftops and exteriors. In his memoir, Lechner wrote that his practice Ödön Lechner and Gyula Pártos,

Iparművészeti Múzeum, Budapest, 1893-

had been particularly influenced by his own family’s brick manufactory,

1896. Photo: Author.

which produced decorative ceramics for many building exteriors, includ-

ing Budapest’s Great Synagogue, executed in 1854-1859 by Frigyes Feszl

and Ludwig Förster. Lechner was particularly attracted to colorful glazed

ceramics. For him, they were a creative medium with deep roots in

traditional Hungarian folk art, which also had the potential of expressing

a true Hungarian modern style.2 Glazed ceramics were not only fireproof

but also easy to keep clean. Less porous than stone or brick, they could

be easily washed, and were especially suitable for the new sooty, urban,

industrial environment of Pest. The Thonet House, 1888-1889, a com-

mercial apartment building in the Váci utca (street) designed by Lechner

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

10 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

FIGURE 2 and Pártos with an innovative cast-iron frame, similarly announced its

Aerial view of Iparművészeti Múzeum. modernity through its cladding of vivid blue Zsolnay tiles.3

Photo: Iparművészeti Múzeum, Budapest.

Jenö Radisics, the museum’s second director, reflected on Lechner’s

distinctive decoration: “The façade speaks to us in a language that

expresses that the modern art of our country is particularly Hungarian; its

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 11

power is inspired by our own artistic past; it proudly proclaims that

Hungarian decorative art engages us in a new vision and provides us the

opportunity to affirm its eminent qualities.”4 Indeed, Radisics, a cham-

pion of Hungarian modernism, speculated that Lechner’s ceramic clad-

ding may actually have had a native Hungarian precedent in the fif-

teenth-century castle of King Matthias Corvinus across the river, in

Buda, where fragments of similar architectural tiles had recently been

discovered.5

Lechner and Pártos won the competition to design the museum in

1890 with their theme, “Go East Hungarian.”6 The exotic decorative

patterns on the museum walls, and the scalloped arches of the interior

loggias, are reminiscent of Persian, Hindu, and Turkish designs. They

echo the Indian art and Oriental ceramics that Lechner encountered on

his visit of 1889-1890 to the new South Kensington Museum in Lon-

don.7 Although the Budapest museum is of course not literally con-

structed of cloth, it incorporates an imaginative fantasy of Oriental

architecture in the tentlike glass canopy suspended over the inner court

and the tapestry-like tiled roof.8 This aspect of the building also alludes

to the tent dwellings of ancient Central Asian nomads, and the remnants

of such architecture in rural Hungarian building styles.9 Lechner was

probably influenced by the designs of Julia and Teréz Zsolnay, daughters

of Vilmos Zsolnay, the company’s founder, who had similarly conflated

Eastern and native Hungarian decorative patterns in their ceramics of

the 1870s and 1880s (Fig. 6). The Zsolnay sisters’ “Persian” patterns were

inspired by the Iznik ceramics of Turkey, brought to Hungary by the

Ottomans during the Turkish occupation of the sixteenth and seven-

teenth centuries, patterns evoking the abstracted tulip and pomegranate

forms in traditional Hungarian folk art.

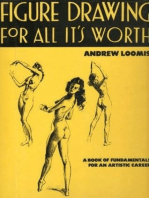

Many have also observed that the stylized floral motifs on the

exterior façade and interior walls (now whitewashed) of the museum are

similar to the ornamentation of certain traditional Hungarian costumes,

such as the suba, or embroidered sheepskin cloak, and the cifraszűr, a

fancy felt “frieze” coat from the Great Plain region (Fig. 7). (In the

nineteenth century, the town of Debrecen was the tailoring center for

cifraszűr production.) Just like the architectural framing of the museum’s

façade, the rectangular cloth panels of the cifraszűr, sewn together to

shape the sleeves, front, and back of the coat, are articulated with

decoration around the seams, forming windows that showcase vivid,

friezelike, embroidered and appliquéd patterns in red and green against a

neutral felt ground. Indeed, Lechner’s new “language of form” was part of

a widespread interest in folk art among Hungarian artists, art historians,

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

12 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

FIGURE 3

Detail of ceramic ornament inside foyer of

Iparművészeti Múzeum. Photo: Author.

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 13

FIGURE 4

Interior of exhibition hall of Iparművészeti

Múzeum. Photo: Author.

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

14 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

FIGURE 5

Detail of façade of Iparművészeti Múzeum.

Photo: Author.

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 15

and ethnographers, who believed that they could discover evidence of an

authentic Magyar spirit with roots in Hindu, Persian, and ancient Sas-

sanian decorative motifs. These designs presumably had been brought to

Europe in the ninth century by nomadic Central Asian tribes, from

which the Hungarians descended. The ethnographer József Huszka was at

the forefront of this search for Magyar ethnic roots in the visual art of

India and Persia, and his ideas were published in many leading Hungar-

ian art journals in the late nineteenth century (Fig. 8).10 In addition to

his interest in the embroidered motifs of shepherd’s cloaks from Hunga-

ry’s Great Plain, Huszka was particularly drawn to the decorative em-

broidery and painted motifs of the folk costume and architecture of

Kalotaszeg in his native Transylvania. As a result of Huszka’s enthusiasm

for the region, publicized in his many sketches, books, and essays, a

generation of modern artists, architects, and designers continued to

search for their own stylistic identities in the ancient vocabulary of

Transylvanian folk art.11

Hungarian Nationalism

Investigations into Magyar ethnicity were politically motivated, as

they were part of a cultural effort to define Hungarian national identity

during the period of the Dual Monarchy. This rule began with the

Compromise of 1867, in which Austria granted semisovereign status to

the Magyar portion of the empire, and it ended in 1918 after World War

I. Although technically still under the “protection” of the Habsburg

emperor Franz Josef via the imperial military and bank, Hungary estab-

lished its own independent administrative infrastructure, with separate

Parliament and ministries, and strove to build an industrial economy that

could compete with Austria’s. As early as the reform period of the 1840s,

Hungarian nationalists, including István Széchenyi, had held up native

ceramics manufactories at Herend, Munkács, and Batiz as evidence that

a commercially viable and aesthetically unique form of Hungarian ap-

plied art could exist.12 The cifraszűr itself was a subversive political

symbol. Habsburg sumptuary laws had outlawed the garment in the

eighteenth century, but later, in defiance, many anti-Habsburg revolu-

tionaries, including the political reformer Lajos Kossuth, began to wear

the szűr, which quickly became associated with Hungarian nationalism.

Lechner’s famous promise “A Hungarian language of form does not yet

exist, but it will!” was an ideological battle cry based on Széchenyi’s

message, “Many think Hungary has been; I like to believe she will be!”13

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

16 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

FIGURE 6 Before Huszka and Lechner began their ethnographic explorations,

Engraving of ceramic dish designed by Júlia the Hungarian art historians Imre Henszlmann (1813-1888) and Arnold

Zsolnay and produced c. 1870- c. 1880 by Ipolyi (1823-1886) had awakened an interest in national art through

Zsolnay Manufactory, Pécs, Hungary. From

their research into and preservation of cultural treasures— especially

Die Österreichisch-Ungarische Monarchie in

Wort und Bild, vol. 5 (Vienna, 1888), 503.

from the late Gothic and early Renaissance periods. Henszlmann, al-

Photo: University of Chicago Libraries. though academically trained in medicine, was tutored in Vienna along-

side Rudolph Eitelberger, who would later become the first director of the

FIGURE 7 Austrian Museum for Art and Industry. In the 1840s, Henszlmann

Suba and szűr, felt shepherd’s cloaks. From became increasingly interested in the study and preservation of historic

Jǒzsef Huszka, “A Debreczeni Czifra Szűr”

monuments in Hungary, especially the restoration of the Gothic cathe-

(The fancy shepherd’s cloaks of Debrecen),

Művészi Ipar 1 (1885-1886): 85-91. Photo: dral in Kassa (today Košice, Slovakia), the city in which he was born. He

Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, provided a plan for the building’s new glazed tile roof, completed in 1860:

Vienna. it is a design that underlines the connections between the geometric

rooftop patterns of the Iparművészeti Múzeum and those of other Gothic

and Gothic Revival churches throughout Austria and Hungary.14 Ipolyi,

a Catholic bishop with an academic background in theology, was particu-

larly interested in Hungary’s folk tradition and its spiritual sources. He

strongly supported the Neo-Gothic direction in Hungarian architecture in

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 17

the late nineteenth century, which reached its culmination in the designs for

Imre Steindl’s (1839-1902) new Parliament building in Budapest. The

building’s ornamental scheme was based on historical studies of medieval

Hungarian decorative arts. Members of the Hungarian clergy, whose per-

sonal collections of ecclesiastical vestments and decorative church objects

supported the idea of a rich and uniquely Magyar aesthetic tradition and

sensibility, were also staunch proponents of the national revival in the arts.15

Historicism was the dominant mode of architecture and industrial

art in both Vienna and Budapest in the late nineteenth century, but it

was inflected differently in each capital. The eclectic buildings along

FIGURE 8

Vienna’s Ringstraße drew on Classical and Gothic traditions, but it was

Detail of traditional suba embroidery. From

ultimately the style of the Italian Renaissance, flavored with elements of

Huszka, “A Debreczeni Czifra Szűr,” color

Habsburg Baroque, that characterized the aesthetic, cultural, and intel- pl., n.p. Photo: Österreichische

lectual aspirations of the city. Rudolf Eitelberger favored the clear and Nationalbibliothek, Vienna.

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

18 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

rational forms of Renaissance architecture and the interior decoration of

August Sicard von Sicardsburg and Eduard van der Nüll’s Staatsoper,

1861-1869. The popular style was the guiding principle behind Heinrich

Ferstel’s design of the Austrian Museum for Art and Industry, 1868-1871,

as well as for Gottfried Semper and Karl Hasenauer’s twin Art History

and Natural History Museums, 1872-1881, and their Burgtheater, 1874-

1888. Stereotypes at the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century

described Vienna and the Viennese character as light and gay. This

identification of the city with “waltzes and pastries” was inextricable from

its architecture. Forming the unmistakable urban landscape of this cap-

ital of art and music were the showy buildings of the Ringstraße and the

cafés in the inner city, as well as the delicate, gilded, pale yellow Rococo

palaces and churches of the eighteenth century, from the era of Maria

Theresa, and the simple white Biedermeier buildings of the early nine-

teenth century.

Budapest, by contrast, is bigger, grander, but also darker and more

looming. Enormous bridges span the Danube and link the medieval city

of Buda, with its castle perched on the hill, to the sprawling industrial

expanse of nineteenth-century Pest. Gothic and early Renaissance styles,

associated with Hungary before it came under Habsburg rule in the

fifteenth century, had a much greater role in Budapest than in Vienna.

In the Hungarian capital, these architectural traditions were intimately

and romantically linked to the legendary events of the nation’s long

history.

Lechner and Pártos were heirs to the work of Frigyes Feszl, whose

Romantic 1859 design of the Vigadó (Concert Hall) in Pest featured

oversized renderings in stone of the ornamental cord (vitézkötés) used to

embellish traditional Hungarian court dress (Fig. 9), and whose designs

with Ludwig Förster for the Great Synagogue also drew on exotic themes

with Gothic and Moorish associations.16 Late medieval and Renaissance

styles were particularly beloved in Budapest, as they signified the “golden

age” of Hungarian history, represented by the enlightened King Matthias

Corvinus, known for establishing one of the largest libraries in Europe,

his extensive patronage of the arts, and his early Renaissance renovations

to the royal castle on the Buda Hill. Miklós Ybl’s Opera House, 1884, and

Imre Steindl’s new Parliament building, 1884-1902, which quickly be-

came a symbol of Hungary’s national heritage, exemplified the Hungar-

ian Renaissance and Gothic Revival styles. Lechner and Pártos experi-

mented with Neo-Renaissance architecture as well, seen, for example, in

their 1883 design of apartment buildings for the Hungarian Railroad

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 19

Pension Fund (today the Drechsler Palace), which directly face and

converse with Ybl’s Opera House across the fashionable Andrassy út.

Hungary’s mythic past was memorialized in monumental form at the

1896 Millennial Celebrations with a pastiche re-creation in Budapest’s

Városliget (Central Park) of the country’s most famous historic buildings.

At the center of the complex was a replica of the fifteenth-century

Transylvanian Vajdahunyad Castle (Fig. 10), residence of János Hu-

nyadi, one of Hungary’s most beloved leaders and father of King Mat-

thias.17 The castle, with its tall square spires, evoked the rural church

architecture of Transylvania’s Székely people, who held a special place in

the Hungarian imagination. Many believed that these mountain inhab-

itants, isolated for centuries and relatively untouched by foreign domi-

nation, still possessed spiritual traces of the original Central Asian

tribesmen from whom they descended. The replica of the castle was so

popular that it was recreated for the Paris 1900 Exposition Universelle as

the Hungarian national pavilion, where it received critical acclaim for its

sensational representation of Hungary’s “bloody past” in Romantic mu-

rals and its lavish display of weaponry (Fig. 11). The Millennial Monu-

ment on Heroes’ Square (Fig. 12), adjacent to the castle complex in the

Városliget, firmly fixed the memory of the nation in a narrative of a

feudal and militaristic past, in which the Eastern barbarian warriors were

slowly civilized, Westernized, and Christianized, all the while maintain-

ing their true character as strong and passionate fighting horsemen. At

the center of the movement, Prince Árpád on horseback leads his fellow

Magyar warriors, representing the seven conquering tribes who settled in

the Carpathian basin in 896. Encircling the central group of horsemen,

enormous sculptures depict over a dozen leaders in sumptuous regalia,

from St. Stephen, János Hunyadi, and Matthias Corvinus to the revo-

lutionary Lajos Kossuth, whose dress also reflects elements of the original

tribesmen’s costume.

By contrast, the exhibitions of modern Hungarian decorative arts at

the 1900 Paris Exposition Universelle were received with more ambiv-

alence by the general public, as they presented a much less comprehen-

sible picture of Hungarian identity. Zoltán Bálint and Lajos Jámbor’s

peculiar framework for the Hungarian installation of decorative arts in

Paris, loosely modeled on the idiom of the Iparművészeti Múzeum,

introduced this specifically “Hungarian” style of modern design to the

international community. The Iparművészeti Múzeum is less fluid in its

form and ornamental style than some of Lechner’s later buildings in

Budapest, such as the Geological Institute, 1898-1899, the Postal Savings

Bank, 1900-1901, and the Sipeki-Balász villa in Hermina utca, 1905-

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

20 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

1906. The more pronounced emphasis on smooth volumes and abstract,

organic line in these buildings relates them to the international Art

Nouveau movement that blossomed at the turn of the century. The new

museum was experimental. It represented Lechner’s sense that a truly

Hungarian native modern style would emerge, but had not yet been fully

articulated.

Lechner and Pártos’s combination of stylistic elements can be un-

derstood as a form of bricolage—a strategy that enabled them to make a

building that bridged the old and the new, as well as to unify very

different manifestations of Hungarian styles. The rooftop design, while

clearly a version of the tiled rooftops of many of Central Europe’s

architectural landmarks, also referred to traditional Hungarian textiles.

Unlike the regionally specific (and politically loaded) patterns of the

cifraszűr, however, or the folk costumes of Kalotaszeg evoked by the

ornamentation of the building’s façade, the geometric patterns of the

rooftop resembled more generalized forms of weaving or cross-stitch

embroidery found throughout Hungarian and Romanian lands (Fig. 13).

It is quite possible that Lechner and Pártos were making a direct refer-

ence to these ubiquitous fabrics, collected before Huszka’s revival of

interest in Kalotaszeg, as they were at the center of Hungary’s exhibits at

the 1873 Wiener Weltausstellung. The Hungarian Parliament had pro-

FIGURE 9

Hungarian man’s gala costume, c. 1860-

1870, detail of vitézkötés on tunic,

traditionally worn beneath a heavy coat.

Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 21

vided a large grant to purchase the four thousand samples of Hungarian FIGURE 10

Ignác Alpár, replica in Budapest of

and Romanian folk embroideries and weaving collected by Florian Franz

Vajdahunyad Castle, Transylvania, 1896.

[Flóris] Rómer, which had been highly praised at the 1873 World’s Fair.

Photo: Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum,

As the goal of the new museum was to illuminate the relationship Budapest.

between traditional crafts and modern Hungarian applied arts, the tex-

tiles provided its material and conceptual foundation.18

Lechner’s references to traditional textiles in the building’s decora-

tive scheme were complex and multivalent. He combined patterns de-

rived from diverse regional forms of needlework and costume with

allusions to the Central Asian origins of the Magyar people, and trans-

lated his narrative of Hungarian history into the medium of ceramic

ornament—a medium that linked Hungary’s ancient roots to its modern,

industrialized present.19 The museum building functions linguistically,

mapping a story of the Hungarian spirit through space and time with

visual symbols. It was quite common at the turn of the nineteenth to the

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

22 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

twentieth century for critics to describe architecture in terms of “lan-

guage”—as a verbal text that could be read and interpreted by the viewer.

In the case of the Iparművészeti Múzeum, this language was specifically

a language of “dress.”20 After his visit to the 1873 Wiener Weltausstel-

lung, Rómer described the fanciful traditional costumes from throughout

Austria-Hungary as a medium for communication, especially as seen on

Viennese trains, where it was possible to “read” a fellow passenger’s

ethnicity and place of geographical origin. In the late nineteenth and

early twentieth centuries, even the smallest regions of Austria-Hungary

were signified by the traditional folk costume worn by its inhabitants.

“National costume” began to function as a visual map for those living in

the capitals of the Dual Monarchy during a period of increasing mod-

ernization and industrialization, in which ethnic and national identities

and allegiances were particularly complex and often confusing.21

The Habsburg court was renowned for its fashionability, which

reached a peak during the reign of Emperor Franz Josef and his wife,

Empress Elizabeth. Because of the great diversity of costume styles

throughout Central Europe, it had long been the custom in Vienna to

appear at court in the gala dress of one’s own native region. The

Hungarian “hussar” costume was the most handsome, exotic, and luxu-

rious form of dress at court. Evolved from the military dress of a nomadic

group of Hungarian horsemen who helped defend King Matthias against

Turkish invaders in the fifteenth century, the hussar’s dress had a kinship

to that of Prince Árpád and his fellow warriors. Because of the success of

the Hussars against the Turks, the hussar costume remained a fashionable

form of court dress into the sixteenth century. In the mid-nineteenth

century, nationalist reformers and politicians, including Lajos Kossuth

and the first Prime Minister of Hungary, Count Gyula Andrássy, also

FIGURE 11 wore this native dress.

Hussar (Hungarian horseman). From Das Lechner envisioned costume—specifically the fancy aristocratic cos-

Österreichische-Ungarische Monarchie in Wort tumes worn at court—as a model for architectural innovation.

und Bild, vol. 5: 221. Photo: University of

Chicago Libraries.

Take, for example, Hungarian gala dress. It had its origins in the

primitive language of form of our people and in the course of time

it has become such an exquisite form of dress that it satisfies a

certain demand not only in Hungary but in the clothing of all

cultured nations of the world. Even the Japanese hussars, when

searching for a special uniform, borrowed Hungarian decorative

motifs. Hungarian festive dress is a mature, developed, generally

accepted concept although it originates from simple forms which

other disciplines (architecture, painting and arts and crafts) could

well develop.22

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 23

The museum’s director Radisics, who supported Lechner’s mission, also

felt it was puzzling that Hungarians should wear such extravagant gala

dress and yet live in “whitewashed rooms,” that is, among furnishings

that lacked a clear stylistic identity or a clearly developed aesthetic with

origins in traditional forms of folk art.23

Apropos of the decorative scheme of the building, Lechner’s ceramic

decoration calls to mind the traditional embroidered patterns of the

cifraszűr and other peasant clothing worn in Transylvania, or Hungary’s

Great Plain. Yet, for the architect, it was the Hungarian gala dress, a

Western aristocratic fashion derived from Eastern tribal costume, that

provided the best model for his new architecture. The building itself may

be read as an example of Western architecture, appropriate for appear-

ance at court, so to speak, based on the traditional vocabulary of

FIGURE 12

civilized, Christian Europe. The tripartite articulation of the façade, with György Zala, Millennium Monument on

more heavily rusticated treatment at the lower level, recalls the tradi- Heroes’ Square, Budapest, 1896. Photo:

tional form of the Italian High Renaissance palazzo. The pointed stone Magyar Nemzeti Múzeum, Budapest.

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

24 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

arches around the windows and the rooftop decoration reflect the late

FIGURE 13

Belt ornament from Naszód, woven cotton, nineteenth-century Gothic Revival and Arts and Crafts movements.

Romanian work, purchased from 1873 While the interior treatment of the walls may refer to Persian or Hindu

Wiener Weltausstellung by Iparművészeti building styles, the encircling structure of the building overall is akin to

Múzeum, Budapest. Color pl. by textile that of an ancient Assyrian palace. The most distinctive feature of the

designer Friedrich Fischbach, in Carl building’s silhouette is the shape of the tall central dome, surmounted by

[Károly] von Pulszky, Ornamente der

a smaller ornamental cupola. Scholars have noted that the larger dome

Hausindustrie Ungarn’s (Budapest, 1878),

pl. 14 B. Photo: University of Chicago is similar to the shape of the ancient Sassanian or traditional medieval

Libraries. hussar’s helmet, as worn by Prince Árpád, while the cupola may resemble

St. Stephen’s crown—a national treasure and a symbol of the nation’s

conversion to Christianity.24 In this sense, Lechner and Pártos transform

Hungary’s Eastern past into its Western present. The dome of the

Iparművészeti Múzeum reflects as well the Neo-Renaissance dome of the

city’s most visible architectural landmark, St. Stephen’s Basilica, a mon-

ument to Hungary’s first Christian king.

Semper’s Influence

Just as Radisics described the façade of Lechner’s new building as

“speaking in an expressive language,” Gottfried Semper had understood

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 25

architecture as a linguistic system, whose visual elements combine and

evolve over time and communicate in a multitude of cultural, historical,

and even spiritual ways.25 Semper’s theory of architecture’s origins in the

decorative arts played a key role in the institutionalization of the applied

arts in Austria-Hungary. Having designed a number of installations at

the 1851 Great Exhibition in London, Semper wrote his influential

treatise, Science, Industry and Art, 1852, in response to the aesthetic

dilemma of England’s rapid industrialization. At the exhibition, he

observed endless permutations of traditional crafts, imitated with new

materials and technology, including ornate furniture and decorative

objects made of cast iron, papier-mâché, and gutta-percha. In these new

objects, artistic style had been perverted, he believed. Technology had

erased the memory of primitive crafts, such as weaving and pottery, and

their symbolic forms. This was especially evident because the hand-

crafted imports from the British colonies abroad, such as woven and

embroidered textiles from India, appeared to possess a great deal more

artistic integrity than England’s modern applied arts.26

Semper envisioned a reform in design education that would involve

learning crafts while following good-quality historical models, which he

outlined in his 1852 manuscript “Ideales Museum für Metallotechnik.”

The ideal design museum, Semper indicated in that manuscript, should

be organized thematically around the four primary elements of architec-

ture: weaving, pottery, carpentry, and masonry. The act of building,

according to Semper’s theory, was founded on these basic media, because

they emerged from the earliest place of social gathering—the hearth. The

ceramic hearth itself had to rest on a stone mound. A joined roof and

wickerwork walls covered and enclosed the surrounding space.27 Sem-

per’s organizational scheme served as the framework for all three of

Europe’s first museums of applied art, the South Kensington Museum in

London, 1857, the Austrian Museum for Art and Industry in Vienna,

1864, and the Hungarian Museum of Applied Art in Budapest, 1874, the

last of which was established nearly two decades before it found its

ultimate home in Lechner’s new building. Each of these museums divided

its collections by media, with departments of textiles, lacquer, enamel,

mosaic, leather, glass, ceramics, wood, iron, bronze, gold, precious stones,

and so forth, in order to illuminate Semper’s theory of the transformation

of artistic style based on media and technique.28 Ferenc Pulszky and

others affiliated with the Society for Applied Arts believed like Semper

that one of the new museum’s most important goals was to improve and

foster a competitive applied arts industry in Hungary. Because Pulszky

and Semper were both exiled revolutionaries in London in 1848, some

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

26 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

have even suggested that it is possible, if not likely, that the two may

have met during that period.29

While each of these four elements was ostensibly an equivalent pillar

of architecture, for Semper textiles had the greatest cosmic significance.

His fullest, and yet still incomplete, articulation of this architectural

theory was finally published in the two-volume compendium Style in the

Technical and Tectonic Arts; or, Practical Aesthetics, 1860-1863. The three

hundred-page section on textiles constitutes Semper’s most extensive

analysis of a single material, and is the part of the book that he chose to

write first. It is here that he formulated his influential Bekleidungsprinzip

(Principle of Dress), which states that a building’s communicative ca-

pacity lies in its decorative cladding. This volume is a dizzying effort to

understand the nearly infinite ways in which textiles are fabricated and

used, as well as the way in which their outward expression evolved from

the architectural styles of ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece, and

Rome, through Byzantium and the early Christian era, to the early

modern period of the Renaissance.

Semper begins his analysis of the textile’s functional properties by

distinguishing among the “band,” the “cover,” and the “seam.” “The

cover’s purpose,” he writes, “is the opposite to that of binding. Everything

closed, protected, enclosed, enveloped, and covered presents itself as

unified, as a collective; whereas everything bound reveals itself as artic-

ulated, as a plurality.”30 Each of these treatments of the textile—whether

using the expanse of its flat surface or joining two surfaces together— had

a symbolic meaning. Seam embroidery, Semper believed, “forms the

actual material basis for all surface ornamentation.”31 Lechner’s building,

with its emphasis on the seam as the source of surface ornament, is a

visual expression of Semper’s idea. The floral motifs, so similar to the

embroidered patterns of cifraszűr, are actually secondary to the ornamen-

tation of the building piers. The building stands out visually not so much

because of the floral decorations, which can only be seen on closer

inspection, but as a result of the marked contrast between the stripes of

dark gray stone piers and the lighter, neutral brick surface between them.

The seam, for Semper, had primeval, mystical significance, especially in

the form of the knot: “The sacred knot is chaos itself; a complex,

elaborate, self-devouring tangle of serpents from which arise all ‘struc-

turally active’ ornamental forms, and into which they irrevocably return

after the cycle of civilization has been completed.”32 This recalls Feszl’s

knotlike ornamentation of the Vigadó, which mimics the tangled inter-

lace form of the braided vitézkötés.

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 27

Among the earliest built structures, Semper wrote, were spaces

divided by hanging mats of woven grasses, as well as temporary festival

tents with cloth canopies, decorated with ribbons and garlands of flowers

and branches. The primary function of the wall was significatory—

orienting the viewer in space. As architecture necessitated sturdier,

load-bearing walls, they were often covered with woven carpets or

tapestries. The spatial delineations—the vertical and horizontal desig-

nations of borders, bands, and hems—were translated into walls, floors,

and ceilings in such a way as to guide the viewer through the built space.

Semper strongly objected to the inappropriate use of directional orna-

ment, such vertical bands on flags (which are meant to flutter horizon-

tally in the wind), or the Victorian fashion of draping Indian scarves over

the shoulders, rather than gathering them in folds, which distorted the

original ornamental motifs, or of decorating tile floors with naturalistic

images, which gave occupants the uncanny sensation of not knowing

where to step in crossing a room. All decorative wall treatments—stucco,

mosaic, paint, or the wicker-like patterns of brick— evoked the symbolic

form of these original textile “dressings.”

Semper saw the clearest historical evidence of the transformation of

textile motifs in ancient Assyrian tile work. In fragments of glazed

architectural ceramics from Babylon and Khorsabad, Semper recognized

the remnants of colorful tapestries, with their vivid black borders and

stylized figural, animal, and vegetal motifs, tapestries that, according to

historical accounts, were hung on palace walls for victory celebrations

and imperial ceremonial processions. The stone, ceramic tile, and later

painted representations of these ceramic wall treatments recreated the

festival adornments in monumental form.33 The use of textile treatments

for festival purposes was at the center of Semper’s theory of the devel-

opment of artistic style over time. From his point of view, the urge to

construct a space was less based on a rudimentary need for shelter than

on a primal human impulse to play with decoration. People had always

ornamented themselves—with wreaths and jewelry—the symbolic pur-

pose of which was to anchor the human body comprehensibly within the

universe.34 In his theory, architectural dress mediates between building

and spectator just as clothing mediates between the individual body and

the wearer’s environment.

Toward the end of his volume on textiles, Semper digresses dramat-

ically, in order to make a connection between the most apparent appli-

cation of textiles, for clothing the human body, and his theory that, “the

principle of dressing has greatly influenced style in architecture and in

the other arts at all times and among all peoples.” Here he asserts that the

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

28 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

oldest principle of architecture is the “masking of reality in the arts.”35

The goal of architectural dressing is simultaneously to express a building’s

ritual meaning and to conceal its inner structure. The once-colorful

painted surfaces of ancient Greek sculpture and buildings represented, for

Semper, the most dematerialized of architectural dressings. Again, he

turned to classical antiquity for his model of theatrical disguise—the

mask. It is not surprising that Semper’s most influential buildings include

the Dresden Opera House, first built 1838, rebuilt 1871—the site of

many performance debuts for his friend Richard Wagner—as well as the

imperial Burgtheater in Vienna, 1874-1888, and the twin museums of art

and natural history, 1872-1881, designed in collaboration with Karl

Hasenauer as part of a festive imperial forum that was never completed.

Semper died on May 15, 1879, just two weeks after the imperial

celebration of Emperor Franz Josef and Empress Elizabeth’s silver wed-

ding anniversary in Vienna. At the extravagant jubilee festival parade,

organized by the painter Hans Makart, thousands of attendants dressed in

historical costume, including Hasenauer, participated in a series of pro-

cessions and represented historic guilds from the sixteenth and seven-

teenth centuries.36 Makart was beloved for his enormous mythological

and history paintings, as well as his portraits of women dressed in

costume from the late Renaissance and Baroque periods. These sumptu-

ous painterly canvases in the style of Titian, Rubens, and Rembrandt

inspired lavish and amusing lebendige Bilder, re-enactments of the scenes

in Makart’s studio with his wealthy patron friends dressed as characters

from the paintings. Makart’s studio itself was famously filled with all sorts

of theater props; it became a symbol of Vienna’s atmosphere of masked

performance in the late nineteenth century. The Makartzeit was domi-

nated by a cultural love of historicism in architecture, fashion, fine and

decorative arts, and its greatest expression could be found in the Vien-

nese passion for masquerade balls during Fasching (Vienna’s long carnival

season). Otto Wagner, Lechner’s contemporary, began his career by

designing temporary pavilions for Makart’s 1879 Festzug, but he later

criticized Vienna’s historicizing architecture, likening the ostentatious

Ringstraße buildings to costumes rented for a masquerade ball.37

Is it possible that Semper’s fascination with the ancient Orient,

which stemmed from his abhorrence of contemporary Western industrial

arts, had a parallel in the Hungarian intellectuals’ search for an exotic,

non-Western identity, in the face of oppressive western Austrian impe-

rialism? The belief that artistic creativity must have a primitive source

pervaded modernist explorations well into the twentieth century. The

famous decoration of Makart’s studio in Vienna with its eclectic and

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 29

exotic array of objects might be seen as a parallel to Lechner’s assimila-

tion of diverse references in the Iparművészeti Múzeum, as well as to

Semper’s encyclopedic synthesis of global and transhistorical styles and

his comprehensive assessment of craft media and techniques.

On closer inspection, it is easy to see that the Iparművészeti Múzeum

reflects various theatrical aspects of Semper’s earlier buildings in Vienna

and Dresden. It announces its presence as a celebratory monument with

a parade of sculptural figures around the roofline much like the Millen-

nial Monument on Heroes’ Square. The 1896 celebrations, like the 1879

Festzug in Vienna, featured elaborate costumed parades, and were fa-

mously attended by Hungarian nobility in gala dress.38 Despite its many

references to the East and to the primitive at home, the Iparművészeti

Múzeum is in effect a Western, historicist building—a palace of the

industrial arts—which bears a remarkable similarity in its general silhou-

ette to Karl Hasenauer’s first sketches for the Kunsthistorisches Museum

in Vienna. Semper’s understanding of architectural dressing was two-

fold. On the one hand, he saw the building’s decorative sheath, or

cladding, as analogous to a flexible cloth wrapper around the structure,

whose symbolic form evoked the historical evolution of architectural

fabrication. On the other, the building’s “dress” was akin to a theatrical

costume which enabled the actor, or building, to embody the social,

ritual function of constructed space.

The Idea for a New Museum

Long before Lechner’s building was erected, artists and intellectuals

had envisioned a national Museum of Applied Arts in Hungary. On

witnessing Austria’s success in the industrial arts at the 1867 Paris

Exposition Universelle, Ferenc Pulszky, then director of the Hungarian

National Museum, the painter Gusztáv Keleti, and the art historian

Flóris Rómer, argued that they too ought to have a public institution for

art and industry in the Hungarian half of the Dual Monarchy.39 This new

institution, they believed, would serve as a repository for the nation’s

treasures: its court costumes, ecclesiastical vestments, fine porcelain, and

the traditional crafts that were their source, such as peasant embroideries,

native ceramics, and the ornamental uniforms and riding gear of medi-

eval soldiers. With a program of public exhibitions, the new museum

would foster an appreciation of Hungarian history and cultural identity,

and through its affiliated school, it would train a new generation of

industrial artists whose designs could energize national industry. By the

time that Lechner’s building was completed, the museum had already

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

30 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

gathered a large collection, comprising objects from the ethnographic

department of the National Museum, private donations, and, most sig-

nificantly, the extensive purchase of peasant embroideries from the 1873

Wiener Weltausstellung.

Although politically a part of the Austrian Empire since the 1867

Compromise, Hungary was always represented as a sovereign nation at

the international exhibitions of the late nineteenth century—a strategy

that drew attention to Hungary’s unique cultural traditions, but one that

usually left her compared to and overshadowed by the industrially and

economically more powerful Austria.40 Hungary had a strong presence at

the 1873 fair, with many exhibitions about the nation’s agriculture,

especially grain, wine, and wool production. The most popular Hungar-

ian exhibits, however, were those that showcased the colorful, pictur-

esque costumes and architecture of rural mountainous regions that ap-

peared to be frozen in time, “unchanged since the Middle Ages.”41

In her prize-winning essay on women’s work at the fair, the Austrian

writer Aglaia von Enderes, Secretary of the Wiener Frauenerwerbe-

verein, praised the Hungarian and Romanian embroidery on display as

part of the exhibition of “National Hausindustrie,” work that had been

collected by Rómer and János Xántus, head of the Ethnography Depart-

ment at the Hungarian National Museum, and that was afterward pur-

chased for the new museum of applied arts. This array of textiles was a

rich treasure, she wrote, compared to more commercially influenced

dilettante work in the women’s building. Of the Hungarian embroideries,

she remarked, “Whole chests full of this work, wonderfully beautiful

things were there to see, a repository of inventiveness in design and in

the execution of stylish motifs.” A number of these examples with their

“fresh beauty,” she believed, could well serve to introduce a new direc-

tion in women’s handicrafts (Fig. 14).42 Hungarian and Romanian hand-

icrafts seemed more pure and intrinsically beautiful than those of other

nations, in part because it was believed that Hungary was not yet as

spoiled by industry as the Austrian half of the Dual Monarchy.43 In fact,

the degenerated state that was associated with the Austrian women’s

work, especially that of dilettantes and students on display in the wom-

en’s pavilion, may have served as a warning call of sorts for Hungarian art

historians like Rómer, whose stated goal was to increase public awareness

of these national treasures, and to bring to light their particular impor-

tance as models for reforming the industrial arts.44

When the Museum of Applied Art first opened to the public, only

a few objects were displayed, in the stairwell of the Hungarian National

Museum. Clearly, this was not the right space for an extensive collection

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 31

of decorative arts with elaborate social and economic goals, and in 1877 FIGURE 14

the works were relocated to the exhibition gallery of a newer building Border of a towel or sheet, silk and gold-

and silver-wrapped silk-thread embroidery

owned by the Society of Applied Arts in Budapest’s recently developed

on linen, Hungarian work. Textile

Andrassy út. This building still did not provide adequate space for the purchased from 1873 Wiener

important collection, however, and it eventually found a fitting home in Weltausstellung by the Iparművészeti

the building designed by Lechner and Pártos, with its inauguration timed Múzeum, Budapest. Color pl. by Fischbach,

to coincide with the grand finale of the 1896 celebrations.45 Semper’s in von Pulszky, Ornamente, pl. 9C. Photo:

scheme underpinned the concept of the museum in Budapest, just as it University of Chicago Libraries.

had in London and Vienna. The displays and storage systems of all three

institutions manifested Semper’s theory of the relationship of crafts to

one another, with hundreds of thousands of sample objects nestled into

glass cases and tucked into labyrinthine corridors.

Textiles and ceramics, “the pot made of fired clay and the

garment decorated with needlework,” were at the center of the new

museum’s collections. Jenö Radisics wrote that these media equally

deserved first place among the museum’s finest objects. Like Semper,

Radisics believed that textiles and ceramics were “the first creations of

primitive man.” “Magyar taste,” he believed, could be perceived in

ancient Hungarian pottery, whose decorative motifs were preserved in

traditional folk ceramics of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nine-

teenth centuries. Embroideries for royal dress and chasubles from the

Middle Ages shared many of the same decorative motifs as the

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

32 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

FIGURE 15

Embroidered chasuble, silk and gold- and

silver-wrapped silk-thread embroidery on

silk, Hungarian work, in Iparművészeti

Múzeum, Budapest. From Magyar

Műkincsek. Chefs-d’oeuvre d’art de la

Hongrie, ed. Eugène (Jenö) de Radisics

(Budapest, 1897), pl. 12. Photo: University

of Chicago Libraries.

traditional folk ceramics, such as simple, stylized floral patterns (Fig.

15). It is not possible to say of ceramics and textiles, Radisics wrote,

that one medium influenced the other; only that they were formed by

“the same aesthetic spirit.”46 The Iparművészeti Múzeum— both its

new building and the institution itself—was a creative, synthetic

response to the intellectual search for Hungarian national identity

within the new disciplines of art history and ethnography, and within

the bureaucratic infrastructure of applied arts education.

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 33

Ethnographic and historic preservation projects were extremely im-

portant throughout the Austrian empire during this period. As the

Habsburgs had no colonies abroad, they were at a distinct disadvantage

in the face of economic competition from England, Germany, and

France. To compensate, Austria looked to its own natural resources,

including its indigenous peasantry, as a source of wealth. Factory pro-

duction of lace and fancy goods, especially with the expansion of the

railroad in the nineteenth century, had crept further and further into the

more distant reaches of the Empire. Manufacturers tapped the inexpen-

sive but skilled labor force available in the peasantry, often providing

native needleworkers with standardized patterns for lace and embroidery

based on popular Western fashions. As these objects were increasingly

displayed at international exhibitions, however, it became clear that

industry had overlooked the real potential of this resource. Traditional

folk arts had a fresh beauty all their own, and cottage industries were

established in both Austria and Hungary that began to generate a certain

amount of income for their rural producers. More significantly, these

objects were at the center of a much farther-reaching intellectual and

economically based reform of the applied arts industry, in which modern

designers, manufacturers, and consumers were trained to appreciate the

formal beauty of traditional folk art, while its producers were educated to

make good-quality and “tasteful” objects.47 The massive reform project

was carried out not only through the collections and exhibitions at the

new museums of applied arts in Vienna and Budapest but through an

extensive network of regional museums and vocational schools of applied

arts throughout the empire as well.

As a political entity fraught with linguistic, religious, and racial

differences, Austria-Hungary relied on costume and clothing, both liter-

ally and metaphorically, to map its geographical territory and to help

come to terms with its own identity in an era of intense political and

economic competition. In 1884 Emperor Franz Josef’s progressive oldest

son, Crown Prince Rudolf, began an ambitious collaborative project to

map and describe in encyclopedic detail the diverse peoples of the Dual

Monarchy, The Austro-Hungarian Monarchy in Word and Image, 1886-

1902. His optimistic goal was to foster unity between the nations, and

experts from both Austria and Hungary were invited to work on the

twenty-four-volume illustrated text.48 Rudolf differed in ideological ori-

entation and temperament from his father, Emperor Franz Josef. Many

believe that in this respect he took after his mother, Empress Elizabeth,

beloved as “Sisi” in both halves of the Dual Monarchy. Rather than

suppress the ethnic and cultural minorities within the Austro-Hungarian

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

34 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

lands beneath the hegemony of the Habsburg court, as had been the case

under Franz Josef’s long and absolute, although relatively peaceful, pros-

perous, and ostensibly benevolent rule, Rudolph wanted to explore the

multicultural diversity of his lands, and to accept and embrace the

diversity of its many inhabitants. Elizabeth had likewise developed an

intense love for Hungary, a close friendship with Prime Minister Count

Gyula Andrassy, and a sympathy toward the Hungarian nationalist cause.

She even learned to speak Hungarian fluently, and preferred to spend her

time there, rather than at court in Vienna. Rudolph never saw the comple-

tion of his project, as he tragically and inexplicably committed suicide in

1889, nine years before his mother was assassinated by an Italian anarchist

in Geneva, foreshadowing the eventual disintegration of the Dual Monarchy

and of the Austrian Empire.

The Aesthetics of the Mask

Lechner and Semper both attempted to synthesize a vast array of

stylistic forms, which spanned space and time. For both, the daunting

project was an effort to make sense of the visual confusion that sur-

rounded them. For Lechner, it took on greater political urgency at the

end of the nineteenth century than it had for Semper, a multinational

architect with ties to Germany, France, England, Austria, and Switzer-

land. Semper’s proposal for a reform in design education, and his call for

change in current methods of industrial manufacturing, had global im-

plications, and they were inspired by a thirst for understanding human-

ity’s place in the cosmos. Lechner and Pártos brought Semper’s proposal

to fruition. The Iparművészeti Múzeum was a material manifestation of

what Semper could only have imagined. The architects engaged Sem-

per’s notion of “dressing” in several ways. First, the ceramic tiles were

employed as a façade covering, the significance of which was as much

symbolic as structural; second, Lechner’s use of ceramics themselves as

well as his allusion to embroidered textiles in the decorative motifs

supported Semper’s conviction that primitive media and techniques were

the true foundation of architecture. The material substance of the build-

ing and its symbolic meaning, however, were also inextricable from

Semper’s concept of the ideal institution—the museum and school of

applied arts—in which architecture’s origin and evolution through ele-

mentary crafts, such as textiles and ceramics, could be explicated in a

historical and scientific manner.

Above all, Semper’s theory of dress had to do with transformation—

the transformation of “style” that happens as culture evolves over time.

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 35

The trajectory of his text leads from the primitive Eastern past to the

civilized Western present, and for him it was the act of transformation

itself—the dematerialization of the dress—that was civilizing, elevating,

and spiritually necessary. Lechner perceived this urgent stylistic trans-

formation in the form of the Hungarian gala dress, which remembers its

Eastern barbarian origins. Traces of the animal past can be found in the

fur-trimmed cloak, feather-topped cap, and leather boots. The leopard

pelt, slung over the shoulder, signifies the virility of the “hot-blooded”

warrior, as does the long mustache—an unmistakable feature of Hungar-

ian men’s fashion. When Lechner evokes shepherd cloaks in his orna-

mentation of the museum, it again recalls hair and skin—the felt and

sheepskin cloaks of the plains shepherds, who live among animals like

their ancient nomadic ancestors. The material of felt itself represents the

uncivilized Other, as it is composed of what are originally unwashed, tangled,

matted knots of animal hair.49 For Semper, however, the knot was the primal

source of stylistic transformation, and Lechner elevates the knotted felt

fabric to the most dematerialized dressing. The façade of the Iparművészeti

Múzeum is no longer primitive folk art made of embellished animal hair,

skin, or earthy clay. Rather, it is civilized, urban, modern architecture.

Semper’s theoretical ideas about “dress” were intimately connected

to a preexisting and pervasive fascination with costume and its deep

cultural significance in Austria and Hungary in the late nineteenth

century. Ákos Moravánsky has written that Semper’s “aesthetics of the

mask” had particular resonance in Central Europe where the concept was

used by architects to express the “fascination of the old, feudal world,

which had by no means disappeared in [that] part of Europe.”50 Lechner’s

Iparművészeti Múzeum expressed Hungary’s feudal past and industrial

present in monumental form. It performed that history in a theatrical,

commemorative, spiritualized manner, in much the same way as the Mil-

lennial Celebrations had throughout Budapest, with festive costumed pa-

rades and the construction of civic landmarks. For Semper, architecture’s

most meaningful quality was its ability to deny reality through the carni-

valesque mechanism of “masking.” As Semper’s biographer, the architectural

historian Harry Francis Mallgrave, writes, “It is through this primordial

masking, as Semper saw it, that one comes to grips with the existential

human condition of alienation.”51

Two of Semper’s followers in Vienna, Otto Wagner and Adolf Loos,

were especially attracted to the concept of dress, both for its application

to the practice of architecture, and for its broader cultural significance.

Many of Wagner’s buildings, such as his Budapest Synagogue, 1870-1873,

and Vienna Majolikahaus, 1898, are particularly evocative of Semper’s

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

36 Studies in the Decorative Arts/Spring-Summer 2009

notion of the textile dressing. Although Wagner disagreed with Semper’s

architectural theories in some respects, he nevertheless conceived of

architecture in terms of clothing, costume, and fashion. Modern man, he

wrote, does not look right wearing Rococo costume while waiting for a

train in a modern train station.52 Wagner believed that a building’s

“clothing” should suit its time and purpose. Loos expanded on Semper’s

language of “Bekleidung” in his writings and buildings, which he con-

flated, it might be argued, with his own personal identity and mode of

dress.53 “Modern man uses his clothes like a mask,” he wrote.54 Modern

dress was what allowed modern man to live his modern life within the

comfortable space of urban anonymity. For Loos, modern architecture

was specifically masculine, but Loos’s suave and urbane modern man,

dressed in well-tailored, understated classics, was quite different from

Lechner’s hero of the Magyar spirit, a shepherd-warrior transformed by

his sensuous gala costume. The psychological dimension of modern

architecture may have had its roots in Semper’s notion of the original

wall as differentiating between the “inner life,” or home, and the “outer life,”

or public space. Modernity brought a constant negotiation between public

and private life, which was mediated by both architecture and dress.

There were differences between this “aesthetics of the mask,” how-

ever, as it was manifested in Vienna and Budapest, twin capitals of the

Dual Monarchy. Whereas Wagner and Loos both employed a rhetoric of

“fashion” to voice their criticisms of culture and of traditional architec-

tural practices and to call for a new style of building appropriate for the

modern age, Lechner relied on the concept of tradition, metaphorically

represented by traditional costume and decorative peasant textiles, in

order to craft his own style for the modern age. It might seem easy, at first

glance, to view as opposites the multiple efforts at the invention of a

modern visual language of form by architects as diverse as Wagner, Loos, and

Lechner. It is more challenging, however, and more fruitful to understand

them as rooted in a shared experience of the multiethnic, multinational

state, searching anxiously for its own identity in a complex time.

NOTES

1. Buda (on the west of the Danube) was admin- Ödön Lechner 1845-1914, ed. Làszló Pusztai and

istratively joined with the cities of Óbuda and András Hadik, exh. cat. (Budapest: Hungarian

Pest (on the east bank of the river) to become Museum of Architecture, 1988), 12-16.

Budapest in 1873.

3. In both its structure and ornamentation the

2. Ödön Lechner, “A Biographical Sketch,” orig- Thonet House resembles contemporaneous Chi-

inally published in A Ház (The House), 1911, cago School architecture by Daniel Burnham,

trans. Catherine Pusztai and András Székeley, in Louis Sullivan, and others. András Hadik, “Ödön

This content downloaded from 131.156.59.191 on Fri, 14 Mar 2014 12:23:52 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Semper and the Budapest Museum of Applied Art 37

Lechner’s Oeuvre,” in Ödön Lechner 1845-1914, Vienna, Heinrich Ferstel’s Votive Church, 1856- Balla, Herend Porcelain: The History of a Hungarian

ed. Pusztai and Hadik, 5-11. 1879, reflects the style of the city’s most important Institution (Budapest, 2003); Éva Csenkey and

Gothic landmark, St. Stephen’s Cathedral. Ágota Steinert, eds., Hungarian Ceramics from the

4. “La façade nous dit dans un langage expressif Zsolnay Manufactory, 1853-2001, exh. cat. (New

que l’art moderne de notre pays tend à être hon- 15. Ernő Marosi, ed., Die Ungarische Kunstge-

York: The Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the

grois, qu’il puise ses inspirations dans notre propre schichte und die Wiener Schule 1846-1930, exh. cat.

Decorative Arts, Design, and Culture, 2002).

passé artistique; elle proclame hautement que l’art (Vienna: Collegium Hungarium, 1983), 9-22.

décoratif magyar se sent de force à s’engager dans 20. Anthony Alofsin has recently interpreted the

16. Moravánsky, Competing Visions, 218.

une nouvelle voie pour peu qu’on lui offre architecture of Central Europe as a multitude of

l’occasion d’affirmer les éminentes qualities qu’il 17. János Hunyadi, a legendary figure in Hungar- “languages” of history, organicism, rationalism,

possède”; Eugène de [Jenö] Radisics, “Le Musée ian history, symbolized Hungary’s resistance to myth, and hybridity. The Iparművészeti Múzeum,

Hongrois des Arts Décoratifs,” in Magyar Műkinc- both the Ottomans and the Habsburgs. A profes- according to this framework, represents the “lan-

sek. Chefs-d’oeuvre d’art de la Hongrie, ed. Jenö sional soldier from Transylvania, Hunyadi guage of myth.” See Alofsin, When Buildings Speak:

Radisics and Jànos Szendrei (Budapest, 1897), 73- achieved international fame in his successful mil- Architecture as Language in the Habsburg Empire and

94. itary defenses again the Turks, and, as a result, was Its Aftermath, 1867-1933 (Chicago, 2006).

granted riches and noble titles, serving as governor

5. Ibid., 81. 21. Rómer, Die Nationale Hausindustrie, 21.

of his region until 1456. During his last years,

6. Piroska Ács, “The Museum of Applied Arts Hunyadi acted as guardian to the young King 22. Ödön Lechner, “So Far There has not been a

(Iparművészeti Múzeum),” in Hungarian Ceramics Ladislaus V, grandson of the Holy Roman Emperor Hungarian Language of Form but There will be,”

from the Zsolnay Manufactory, 1853-2001, exh. cat., Sigismund of Austria, and when he died, Ladi- originally published in Művészet (Art), 1906, trans.

ed. Éva Csenkey and Ágota Steinert (New York: slaus’s uncle, Ulrich of Cilli, wary of Hungary’s Catherine Pusztai and András Székeley, in Ödön

The Bard Graduate Center for Studies in the Dec- devotion to Hunyadi, assassinated the general’s Lechner 1845-1914, ed. Pusztai and Hadik, 17-23.

orative Arts, Design, and Culture, 2002), 201-4. oldest son, László, and imprisoned his youngest

son, Mátyás, in Prague. Following a bloody battle 23. Radisics, “Le Musée Hongrois,” 74.

7. Katalin Keserü, “Magyar-Indiai Épı́tészeti Kapc- for control of the Hungarian crown, Mátyás 24. Alofsin, When Buildings Speak, 135.

solatok (Indian-Hungarian Architectural Connec- emerged victorious in 1458, ushering in centuries

tions),” Néprajzi Értesı́őö 77 (1995): 167-82. of epic accounts of the heroic feats of the Hunyadi 25. Harry Francis Mallgrave, Gottfried Semper: Ar-

family. See Paul Lendvai, The Hungarians: A Thou- chitect of the Nineteenth Century (New Haven and

8. Ákos Moravánsky, Competing Visions: Aesthetic

sand Years of Victory in Defeat (Princeton, 2003), London, 1996), 284; Debra Schafter, The Order of

Invention and Social Imagination in Central European

75-59. Ornament, the Structure of Style: Theoretical Foun-

Architecture, 1867-1918 (Cambridge, Mass., 1998),

dations of Modern Art and Architecture (Cambridge,

225. 18. Kiss, “Die Entwicklung der Kunstgewerbli- U.K., 2003), 32-44.

chen,” 22; Hilda Horváth, “Ferenc Pulszky and the

9. Aladár Kriesch-Körösfői, “Hungarian Peasant

Movements in Applied Arts in Hungary,” in Ferenc 26. Gottfried Semper, Wissenschaft, Industrie und

Art,” in Peasant Art in Austria and Hungary, ed.

Pulszky (1814-1897) Memorial Exhibition, ed. Kunst: Vorschläge zur Anregung nationalen Kunstge-

Charles Holme (London, 1911), 31-46; Gusztáv

Ibolya Laczkó, Júlia Szabó, and Lı́via Tóthné fühles, bei dem Schlusse der Londoner Industrie-Aus-

Keleti, “Die Kunst,” in Skizze der Landeskunde Un-

Mészáros (Budapest, 1998), 165-69; Carl [Károly] stellung (1852), trans. as “Science, Industry, and

garns, ed. Karl Keleti (Budapest, 1873), 142-46.

von Pulszky, Ornamente der Hausindustrie Ungarn’s Art: Proposals for the Development of a National

10. József Huszka, Maygar Ornamentika (Budapest, (Budapest, 1878). The majority of medals awarded Taste in Art at the Closing of the London Indus-

1898). See also idem, “A Debreczeni Cifra Szür” to exhibits of “National Hausindustrie” at the 1873 trial Exhibition,” in Gottfried Semper, The Four

(The Debreczen Embroidered Cloak), Művészi Ipar Wiener Weltausstellung went to Hungary and Elements of Architecture and Other Writings, trans.

1 (1885-1886): 85-91. Croatia (one of the lands of the Hungarian crown Harry Francis Mallgrave and Wolfgang Herrmann

at the time). See also Florian Franz [Flóris] Rómer, (Cambridge, U.K., 1989), 130-67.

11. Támas Hofer and Éva Szacsvay, “The Discov- Die Nationale Hausindustrie auf der Wiener

ery of Kalotaszeg and the Beginnings of Hungarian 27. Gottfried Semper, “Practical Art in Metals

Weltausstellung 1873 (Budapest, 1875), 32.

Ethnography,” trans. Elayne Antalffy (Budapest, and Hard Materials: Its Technology, History and

Museum of Ethnography, 1998) [virtual exhibi- 19. Although textiles were the most readily col- Styles,” 1852 (unpublished manuscript in the Na-

tion: http://www.neprajz.hu/kalotaszeg/angol.htm]. lected, exhibited, and debated form of folk art at tional Art Library at the Victoria and Albert Mu-

the fair, ceramics played a much more significant seum, London). Semper gave a copy of this manu-

12. Ákos Kiss, “Die Entwicklung der Kunstge- role in Hungary’s development of an advanced script, with a new title, “Ideales Museum für

werblichen Bewegung und das Enstehen der Kunst- applied arts industry. The fine porcelain manufac- Metallotechnik, ausgearbeitet zu London im Jahre

gewerbemuseen,” Ars Decorativa 1 (1973): 7-29. tory Herend, founded in 1826, was already inter- 1852,” to Rudolph Eitelberger in 1867 for the

13. Moravánsky, Competing Visions, 223. nationally recognized by the time of the 1873 library of the k.k. Österreichisches Museum für

Weltausstellung, and would soon be matched by Kunst und Industrie (today the MAK—Öester-