Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sheila & Heng (2018) - APEL Performance

Uploaded by

Thulasidasan JeewaratinamOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Sheila & Heng (2018) - APEL Performance

Uploaded by

Thulasidasan JeewaratinamCopyright:

Available Formats

Accreditation of Prior Experiential Learning (APEL):

An Alternative Entry Route to

Higher Education in Malaysia

Sheila Cheng and Heng Loke Siow

Asia e University

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

Abstract. In general, all parents, rich or poor, want their children to go to school

and receive the best education they can afford. However, in reality, not all

children are blessed with this opportunity for many reasons, mainly financial.

Studies have revealed that educational attainment is a critical determinant of

economic progress (Ariagada, 1986; Barro, n.d; Barro and Lee, 2001; Cole and

Geist, 2018; Psacharopoulos and Ariagada, 1986). According to statistics from

Human Resources Malaysia 2016, 20.8% of youths (15–24 years of age) and

29.2% of adults (aged 24 to 65) attained the tertiary level of education, indicating

that Malaysia still has a lot of room for improve in its economic development. In

order to encourage more eligible candidates to upgrade their education level and,

at the same time, promote lifelong learning, the Ministry of Education Malaysia

launched the APEL (Access) in 2011, as an alternative entry into tertiary

education. This paper aimed to compare the academic performance in the

undergraduate degree programme between the entrants admitted through APEL

(A) and those who came through the standard academic admission route.

Although there is extensive literature on the recognition of prior experiential

learning (RPL), few researchers have looked at the relationship between entry

route and academic performance, especially in Malaysia. A sample of 30

undergraduate adult learners were selected from a private institute of higher

learning in Malaysia; and a comparison of their academic performance with

standard route entrants in a selected semester was conducted. The study showed

that there was no significant difference in the academic performance between the

two groups, with adult learners performing as well as the young learners. These

findings could help to build confidence in educators and policy-makers in

accepting and giving a second opportunity to adult learners to pursue their

educational dream.

Keywords: Accreditation of Prior Experiential Learning (APEL), academic

performance, lifelong learning.

241 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

1 Introduction

Studies revealed that educational attainment is a critical determinant on economic

progress (Cole & Geist, 2018; Schanzenbach, Boody, Memford, & Nantz, 2016;

Barro & Lee, 2001; Psacharopoulos & Ariagada, 1986).

In many African countries, education, especially the “post-primary education and

training” has been recognised as an important pillar to poverty reduction, job-creation,

and progression to knowledge-based societies (Singh, 2008).

“While Education for All (EFA) is good, it is not possible to wait for the

achievement of universal coverage of primary education, especially as many children

and youth in marginalized, and rural and urban contexts, need to develop alternative

access programmes for individuals to progress into TVET, skills development and

adult and community educational programmes.” (Singh, 2008, p.7)

Malaysia has sustained rapid and inclusive economic growth for close to half a

century. In its 11th Malaysia Plan, Malaysia set itself the target of achieving high-

income status by 2020. Fostering lifelong learning and reskilling is one of the

developmental objectives. In the report of OECD (2016), Better Life Index,

Malaysia 2016: Economic Assessment, it was noted that Malaysia scored well in

some areas such as long-term unemployment (Figure 1), it scored relative weak in

area of educational attainment and skills. Improving education quality and skills

training is essential to achieve productivity gains while promoting social cohesion and

well-being over the longer term (Koen, V., Asada, H., Nixon, S., Habeeb Rahuman,

and Mohd Arif, 2017).

242 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

Fig. 1. Well-being indicators point to further opportunities to foster inclusive growth

(Source: Koen, V., Asada, H., Nixon, S., Habeeb Rahuman, M. R. and Mohd Arif, A.Z.,

2017, p.11)

Thus, lifelong learning has been identified as a strategic shift that will propel

Malaysia towards achieving the status of a high income economy and developed

nation.

In supporting the national agenda of lifelong learning, the Malaysian Qualifications

Agency (MQA) through its MQA Act 2007 (Act 679), introduced the provision of

Accreditation of Prior Experiential Learning (APEL) in 2011 to provide access and

opportunities for individuals to pursue tertiary education. Through APEL, MQA

recognises the value of learning that takes place beyond the formal classroom settings

as well as learning that occur throughout work and life experiences; regardless of

when, where and how it was acquired.

In another word, through APEL, individuals who have work experience but lack of

formal academic qualifications are allowed to pursue their studies at higher

educational institutions. In general, knowledge obtained through formal education

and working experience will be both assessed in APEL’s assessment.

In Malaysia, APEL has been identified as a pathway to access the various levels of

qualifications set under the Malaysian Qualifications Framework (MQF). Table 1

summarises the comparison between the standard entry and the APEL entry route to

the different levels in the tertiary education.

243 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

Table 1. Malaysian Qualifications Framework for Standard Entry VS APEL Entry

Requirements

Standard entry requirements APEL entry requirements

under the policy of Ministry of Higher

Education

Certificate programme - minimum Certificate (Level 3, MQF) - 19 years old

of 1 credit at SPM level at the time of application with relevant work

experience and passed APEL assessment.

Diploma programme - minimum of Diploma (Level 4, MQF) - 20 years old at

3 credits at SPM level the time of application with relevant work

experience and passed APEL assessment.

Foundation or pre-U - minimum of 5

credits at SPM level

Bachelor's degree - various pre- Bachelor's (Level 6, MQF) - 21 years old at

university qualifications such as the time of application with relevant work

foundation programme, A level, experience and passed APEL assessment.

STPM and so on.

Master's (Level 7, MQF) - 30 years old at

the time of application with at least

STPM/Diploma/equivalent, relevant work

experience and passed APEL assessment.

(Source : StudyMalaysia.com, 2016)

From the MQA statistics, at the beginning of 2011 until August 2015, 651

candidates applied for APEL. Out of this figure, 211 candidates (32%) choose to

apply for APEL assessment at diploma level; 181 candidates (28%) choose to apply

for APEL assessment at bachelor's degrees level; and 259 candidates (39%) choose to

apply for APEL assessment master's degrees level. During that period, a total of 360

candidates have passed the APEL assessment.

2 Literature Review

Accreditation of Prior Experiential Learning (APEL) is part of the Malaysian

Government’s effort in recognizing the importance of lifelong learning in nation’s

human capital development and knowledge society to achieve its goals of becoming a

developed nation by the year 2020.

In some developed countries, the recognition of prior experiential learning was not

new. Garnett & Cavaye (2015) reported that the development of recognition of prior

learning (RPL) was started in England in 1980s and in Australia, RPL was

introduced in 1992 as part of the national framework for the recognition of

training. However, only in the last few years that RPL has become clearly or

widely adopted by the higher education industry in Australia.

Bohlinger, S., Dang, K., & Klatt, M. (2016) reported education policy across ten

countries including Australia, Austria, Canada, France, Germany, Ireland, the

244 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

Netherlands, Italy, Spain and Switzerland by reviewing, comparing and contrasting

policies and practices of prior learning. She identified that prior learning is an

umbrella term for any kind of learning outcomes gained in various learning settings.

RPL is the process of identifying, assessing and recognising any learning results that

were acquired by individuals in different learning contexts outside formal education

and training systems. She also pointed out that although many European countries

try to make a distinction between formal, non-formal or informal learning and its

outcomes, most of the non-European countries are more common in adopting the term

‘prior learning’.

UNESCO Institute of Lifelong Learning (UIL) (2013) argued that formal learning

is not sufficient to facilitate and utilize the full human potential of any society. It

proposed that recognition, validation and accreditation (RVA) of learning in formal,

non-formal and informal settings is an important instrument for comparing different

forms of learning, in order to eliminate discrimination against those who acquire

competences non-formally or informally. “In a lifelong learning system, learning

opportunities must be made available through all channels: formal, non-formal and

informal.” (Yang, 2015, p.11).

Signh and Duvekot (2013) reported that 23 countries such as Netherlands, Norway

Denmark, Frances, Portugal, Namibia, Afghanistan, Republic of Korea, etc supported

the exchange of experience with RVA systems in the Hamburg Conference organised

by UNESCO Institute in 2010.

Report by Deutsches Institut für Erwachsenenbildung (DIE) in 2003 recognised

that APEL has an important role in development of a learning society. “APEL has

the potential to contribute significantly towards higher education by offering a

flexible approach to learning, opening up institutions to new groups of learners and

developing partnerships with outside organisations.” (p.55).

Although many countries adopted the name “APEL”, some acronyms are used to

differentiate the slightly different things such as Accreditation of Prior Learning

(APL), and Accreditation of Prior Certificated Learning (APCL). “APL and APEL

are often used interchangeably yet the former refers to certificated prior learning

gained in formal learning such as “organised courses, modules, workshops, seminars

and similar activities” (Nyatanga/Forman/Fox 1998, p 7). In Australia the process

is called Recognition of Prior Learning (RPL). The ‘A’ in APEL stands for

accreditation in some situations and assessment in other” (DIE, 2003, p.57-58)

In Malaysia, APEL was introduced in 2015 for admission and credit award in

2016, as a national higher education framework.

APEL is referred to “a systematic process that involves the identification,

documentation and assessment of prior experiential learning to determine the extent to

which an individual has achieved the desired learning outcomes, for access to a

programme of study and/or award of credits.” (MQA, 2015).

Asia e University is among the pioneering institutions in Malaysia to implement

the APEL admission. This paper attempted to review the acceptance of learners

through APEL entry as well as their academic performance compared to the learners

through the standard route entry.

245 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

3 Methodology

This study adopted a quantitative approach to analyse the similarities and differences

on the academic performance of leaners through a standard entry and APEL entry.

A set of questionnaires was sent to students who registered the undergraduate

programme Bachelor of Education (Teaching Islamic Studies in Primary School)

through APEL admission route.

Questions were grouped into three categories namely, (i) the personal information

and background, (ii) what drove these learners to come back to study?, and (iii) who

had motivated them to come back to study?. Last but not least, what challenges

students faced when they returned to study?

There were 166 candidates applied for the programme in May 2016, 121

candidates registered for the programme. However, along the semester, due to

various reasons, 16 of students had withdrawn from the programme and left with 105.

In this study, only 57 students returned their survey questionnaires in completeness.

In terms of academic performance, May 2016 semester results were compared

between the learners admitted through APEL entry and the standard route entry.

Under the authority guidelines, adult learners are only allowed to take up less than

nine credit hours per semester. This batch of learners registered for eight credit

hours in three courses namely, Academic Writing (MPU3222), Hubungan

Etnik/Ethnic Relations (MPU3113) and Tamadun Islam dan Tamadun Asia/Islamic

Civilisation and Asia Studies (MPU3222). These courses were the general subjects

but were considered as compulsory by the local qualifications authority (MQA). All

students in the degree programme must take and pass these subjects.

4 Findings

With 57 returned survey questionnaires, there were 49 females and 8 males

respondents in this study, with 37% (21) respondents of them aged below 30, 40% (23)

respondents aged 30-40 and 23% (13) respondents aged 41-50.

About 70% (40) respondents have the highest qualification of Form 3 (Lower

Certification of Education) and about 14% (8) respondents have Form 5 or equivalent

to School Certificate. About 74% (42) respondents indicated that the reason of not

able to continue their formal education was due to financial constraints, while another

37% (21) respondents were due the inability to meet the academic requirements. But

majority of them had more than 5 years of working experiences. Parents, partners

and friends were the ones motivating them to continue to study. The most important

reason to pursue an undergraduate degree was to develop higher-level skills for their

current profession or extension of knowledge for their current profession

One of the challenges was to manage their studies while working, whereby

respondents indicated that they had to spend around three to six hours each week

studying at home. Other than finding not enough time to sleep and time to finish

assignments, the biggest challenge faced by these learners was the stress in finding a

balance between work and study. However, they did enjoy study in terms of gaining

new knowledge, feel fulfilling and self- achievement.

246 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

For the perception of APEL, majority of respondents agreed that APEL entry had

given them an opportunity to come back and study, and was a good option for

working adults. However, when asked whether they would recommend friends to go

through APEL entry for those who wanted to study but have no formal qualification,

majority of them answered “undecided”. This was quite unexpected and hence,

further study would be recommended.

When they were asked about the future plan, 100% of the respondents replied they

had only one. They would like to continue to work but at a higher position or start

their own business, and 33% (19 respondents) would like to continue their studies.

In terms of academic performance, the assessment consisted of two major

components: 60% assignments and 40% examination. Although assignment

submission deadline was set in each semester, students in this part-time mode were

given an additional period of two semesters for submission of assignment as well as

examination deferment if they so required. However, if a student had exhausted the

two semesters’ gracious period, he/she had to re-enrol the course. The practice of “I =

incomplete” is the unique feature in the University’s assessment system and was

implemented in 2017. The definitions of different categories of “I” are shown in

Table 2 based on students’ needs over years.

Table 2. Incomplete Status

ABS

AR

Absent without

Absent with Reason

Reason

Status (Absent in Exam with

(Absent in Exam

reason and submitted

without reason and

Assignment)

submitted Assignment)

I/AR I/ABS

I Incomplete / Absent Incomplete / Absent

Incomplete with Reason without Reason

(Non-submission of (Non-submission of (Non-submission of

Assignment and still Assignment and still within Assignment and still

within the permissible 2 the permissible 2 semesters within the permissible 2

semesters) and absent in Exam with semesters and absent in

reason) Exam without reason)

IE/ABS

IE/AR

IE Incomplete &

Incomplete & Expired

Incomplete & Expired / Absent

/ Absent with Reason

Expired without Reason

(Non-submission of

(Non-submission of (Non-submission of

Assignment and at the

Assignment and at the Assignment and at the

expired semester for

expired semester for expired semester for

submission and absent in

submission) submission and absent in

Exam with reason)

Exam without reason)

247 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

Academic status is categorised into the following Table 3:

Table 3. Academic Status

Academic Status in term of Remark

Grade Point Average (GPA)

Completed Completed all required credit hours of a

programme

GS Good standing i.e. GPA ≥2.0

PS Probation standing i.e. GPA<2.0

I Incomplete

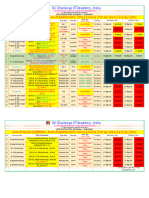

Following Figure 2 shows the academic performance of APEL learners’ versus the

overall learners’ academic performance in May 2016 semester.

Fig. 2. Academic Performance of APEL Learners versus Overall Learners in May

2016 Semster

Figure 2 indicates that in summary, APEL learners did well with all having “GS”

(good standing) in their academic status in the May 2016 semester compared to the

overall students’ academic performance.

In terms of each course, namely MPU3113, MPU3222 and MPU3123 as indicated

in Figures 3, 4 and 5 respectively, more than 90 percentile APEL learners performed

better than “C” – the passing grade in all three courses. Overall, about 12% of the

learners were not able to complete all three subjects.

The grading scale is attached at Appendix.

248 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

Fig. 3. Academic Performance of APEL Leaners versus Overall Learners for

Course MPU3113

Fig. 4. Academic Performance of APEL Learners versus Overall Learners for Course

MPU3222

249 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

Fig. 5. Academic Performance of APEL Learners versus Overall Learners for Course

MPU3123

5 Conclusion and Recommendation

The findings of this study indicate that APEL route entry learners performed no

difference from the standard route entry. In fact, some cases even performed better

and were able to complete their enrolled courses. Although a more flexible system

was adopted by allowing an additional period of two semesters, about 10% of learners

were still unable to cope and dropped out along the way for both groups of learners.

Regardless of the entry modes, most adult learners, time management was the most

important factor, to strike a balance between work, family and social life was not an

easy task. They needed self-determination and motivation to carry on. With the

technology development, many learners could learn through on-line and study at their

own time and own pace. As an educational institution, instructional designers and

policy makers should constantly look into the changes and needs of learners to

develop a lifelong learning society.

250 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

References

Barro, R. (1991). Economic Growth in a Cross Section of Countries. The

Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 106, Issue 2, 1 May 1991, Pages

407–443, https://doi.org/10.2307/2937943

Barro, R.J. and Lee, J. W. (2001). International data on educational attainment:

updates and implications. Oxford Economic Papers, Volume 53, Issue 3, 1

July 2001, Pages 541–563, https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/53.3.541.

https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/8227297/p_jwha.pdf?AW

SAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1525585272&Sign

ature=iPGOGbr8Xsgf9TmxjzWe8uNA8Mw%3D&response-content-

disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DInternational_data_on_educational_at

tain.pdf

Bohlinger, K. Dang, & M. Klatt. (2016). On the notion of education policy: Mapping

its landscape and scope. In S. Bohlinger, K. Dang, & M. Klatt (Eds.),

Education Policy: mapping the landscape and scope. Bern: Peter Lang

Publishers.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/297518700_On_the_notion_of_educ

ation_policy_Mapping_its_landscape_and_scope

Cole, W, M. and Geist, C. (2018). Progress without progressives? The effects of

development on women's educational and political equality in cultural context,

1980 to 2010. Sociology of Development, Vol. 4 No. 1, Spring 2018; (pp. 1-

69) the University of California Press. DOI: 10.1525/sod.2018.4.1.1

Deutsches Institut für Erwachsenenbildung (DIE) (2003). Report 4/2003

Literaturund Forschungsreport Weiterbildung.

https://www.die-bonn.de/doks/report0304.pdf

Garnett, J. and Cavaye,A. (2015). Recognition of prior learning: opportunities

and challenges for higher education. Journal of Work-Applied

Management, Vol. 7 Issue: 1, pp.28-37.

https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/full/10.1108/JWAM-10-2015-001

Koen, V., Asada, H., Nixon, S., Habeeb Rahuman, M. R. and Mohd Arif, A.Z.

(2017). Malaysia's economic success story and challenges. Economics

department working papers no. 1369. OECD

MQA (2015). APEL – Accreditation of Prior Experiential Learning.

http://www2.mqa.gov.my/APEL/en/index.html

OECD (2016). OECD Economic Surveys: Malaysia Economic Assessment.

https://www.oecd.org/eco/surveys/Malaysia-2016-OECD-economic-survey-

overview.pdf

Psacharopoulos, G. and Arriagada, AM. (1986). The educational composition of

the labour force: an international comparison. Int'l Lab. Rev. HeinOnline

http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/663961468135311923/pdf/edt38.p

df

Schanzenbach, D. W., Boody, D., Memford, M., & Nantz, G. (2016). Fourteen

Economic Facts on Education and Economic Opportunity. Brookings: The

Hamilton Project.

251 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

Singh, M. (2008). Creating Flexible and Inclusive Learning Paths in Post-Primary

Education and Training in Africa: Contribution of NQF and Recognition of

experiential and prior non-formal and informal learning. The Key to Lifelong

Learning. Biennale on Education in Africa (Maputo, Mozambique, May, 5-9

2008). Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA) –

2008

Signh, M. and Duvekot, R. (2013). Introduction. In M. Signh, and R. Duvekot (Ed.),

Linking Recognition Practices and National Qualifications Famewoks.

Hamburg, Germany UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning.

StudyMalaysia.com (December 2, 2016). Accreditation of Prior Experiential

Learning (APEL): An Alternative Entry Route to Higher Education

https://www.studymalaysia.com/education/top-stories/accreditation-of-prior-

experiential

UNESCO Institute of Lifelong Learning (UIL) (2013). Annual Report 2012.

http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0022/002203/220310e.pdf

Yang, J. (2015). Recognition, Validation and Accreditation of Non-formal and

Informal Learning in UNESCO Member States. UNESCO Institute of Lifelong

Learning (UIL).

252 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

APPENDIX

Grade System (excerpt from Students’ Handbook, p.27)

253 International Conference on Open and Innovative Education (ICOIE 2018)

You might also like

- School FinanceDocument22 pagesSchool FinancehuixintehNo ratings yet

- Precious ProjectDocument30 pagesPrecious ProjectDinomarshal Pezum100% (2)

- RevisedDocument9 pagesRevisedJenine AlbinoNo ratings yet

- Ijriar 03Document15 pagesIjriar 03Student SampleNo ratings yet

- Developing and Retaining A First-World Talent Base: Kuala Lumpur TowerDocument53 pagesDeveloping and Retaining A First-World Talent Base: Kuala Lumpur TowerNoorayu JayusNo ratings yet

- Quality Management SystemDocument17 pagesQuality Management SystemMustafa TopeNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Lifelong Learning Opportunities in Brunei DarussalamDocument25 pagesAn Overview of Lifelong Learning Opportunities in Brunei Darussalamapi-330120353No ratings yet

- Pre Final Action ResearchDocument18 pagesPre Final Action ResearchAubrey Jenne DiazNo ratings yet

- Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025 Executive SummaryDocument48 pagesMalaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025 Executive Summaryluke kennyNo ratings yet

- Malaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025 - Executive SummaryDocument48 pagesMalaysia Education Blueprint 2013-2025 - Executive Summaryjack100% (3)

- Evaluation of The Funding Benchmarks of The 2009 Nigeria's Educational Reforms in Selected Federal Tertiary InstitutionsDocument9 pagesEvaluation of The Funding Benchmarks of The 2009 Nigeria's Educational Reforms in Selected Federal Tertiary InstitutionsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Basic Education: Education Learning and Development ModuleDocument21 pagesBasic Education: Education Learning and Development ModuleOliver356No ratings yet

- Outcome-Based Education in AccountancyDocument13 pagesOutcome-Based Education in Accountancypotato ssihNo ratings yet

- RMSA Final Framework Submitted in MHRD-A Doc Collected by Vijay Kumar HeerDocument65 pagesRMSA Final Framework Submitted in MHRD-A Doc Collected by Vijay Kumar HeerVIJAY KUMAR HEERNo ratings yet

- Cost Benefit Analysis in Malaysian Education: Husaina Banu KenayathullaDocument18 pagesCost Benefit Analysis in Malaysian Education: Husaina Banu KenayathullaMusrilNo ratings yet

- SKSU-College of Nursing Tracer StudyDocument22 pagesSKSU-College of Nursing Tracer StudyJonaPhieDomingoMonteroIINo ratings yet

- Implementation of Problem-Based Learning DraftDocument20 pagesImplementation of Problem-Based Learning Draftemmanuel ododoNo ratings yet

- Cost Benefit Analysis in Malaysia Educational - Vol 4, No 02 (2010)Document22 pagesCost Benefit Analysis in Malaysia Educational - Vol 4, No 02 (2010)AliaaNo ratings yet

- Republic of The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesRepublic of The PhilippinesPrecillaNo ratings yet

- TVL Research PaperDocument12 pagesTVL Research Papercaister samatra92% (12)

- AMG Full Paper Final PDFDocument126 pagesAMG Full Paper Final PDFAngelica Flor S. SimbulNo ratings yet

- Strategic Planning To Transform Malaysian TVET Students Into Future Ready ProfessionalsDocument11 pagesStrategic Planning To Transform Malaysian TVET Students Into Future Ready ProfessionalsMyra EmyraNo ratings yet

- Marketability of The SHS of SNADocument28 pagesMarketability of The SHS of SNAHirai ChiseNo ratings yet

- CMO No. 74 S. 2017 Policies, Standards and Guidelines For Bachelor of Elementary Education (Beed)Document2 pagesCMO No. 74 S. 2017 Policies, Standards and Guidelines For Bachelor of Elementary Education (Beed)Annalou PialaNo ratings yet

- Educational System in SingaporeDocument76 pagesEducational System in SingaporeJOHNNY GALLANo ratings yet

- Language InstituteDocument11 pagesLanguage Institutemilton777No ratings yet

- Total Quality Management in The Implementation of STVEP in Region XDocument106 pagesTotal Quality Management in The Implementation of STVEP in Region XBlair Dahilog Castillon100% (6)

- E.M.N.D.K.Ekanayaka 2022me07Document3 pagesE.M.N.D.K.Ekanayaka 2022me07Niluka EkanayakaNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Eteeap FinalDocument23 pagesBenefits of Eteeap FinalDj22 Jake100% (2)

- Overview of Philippine EducationDocument45 pagesOverview of Philippine Educationmarkjosephbual14No ratings yet

- FANEP 21augDocument32 pagesFANEP 21augSakshi SodhiNo ratings yet

- Nep 2020Document47 pagesNep 2020pms.41bncsNo ratings yet

- Impact of Education Levels On Economic Growth in MalaysiaDocument14 pagesImpact of Education Levels On Economic Growth in MalaysiaLIN YUN / UPMNo ratings yet

- Accreditation of Prior Experiential LearningDocument20 pagesAccreditation of Prior Experiential LearningEverboleh ChowNo ratings yet

- Sample ProposalDocument7 pagesSample ProposalLorence Miguel ArnedoNo ratings yet

- SingaporeDocument11 pagesSingaporepoisonboxNo ratings yet

- Issues and Challenges Implementation of Basic Education and VocationalDocument10 pagesIssues and Challenges Implementation of Basic Education and VocationalfaridahmarianiNo ratings yet

- 289-Article Text-721-1-10-20170126Document6 pages289-Article Text-721-1-10-20170126A S HNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Nine-Year Schooling On Higher Learning in MauritiusDocument13 pagesThe Impact of Nine-Year Schooling On Higher Learning in MauritiusAnushka SeebaluckNo ratings yet

- EthiopiaDocument6 pagesEthiopiaaamichoNo ratings yet

- TANEDO, DK - DISSERTATION 2019 (PHD) As of 03APRIL2019Document87 pagesTANEDO, DK - DISSERTATION 2019 (PHD) As of 03APRIL2019Donards Kim Abracia TañedoNo ratings yet

- Marketing Plan Bachelor of Elementary Education (ETEEAP)Document7 pagesMarketing Plan Bachelor of Elementary Education (ETEEAP)Caila Chin DinoyNo ratings yet

- EU India Education Forum PDFDocument15 pagesEU India Education Forum PDFVaibhav AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Problems and Challenges Encountered in The Implementation of The K To 12 Curriculum A Synthesis PDFDocument15 pagesProblems and Challenges Encountered in The Implementation of The K To 12 Curriculum A Synthesis PDFRonald EdnaveNo ratings yet

- Updated Reasearch Running Header FooterDocument32 pagesUpdated Reasearch Running Header FooterErica SantiagoNo ratings yet

- FrameworkDocument62 pagesFrameworkDaniel Vinluan Jr.No ratings yet

- The Employment Profile of Graduates in A State University in Bicol Region, PhilippinesDocument9 pagesThe Employment Profile of Graduates in A State University in Bicol Region, PhilippinesD EbitnerNo ratings yet

- Newly 2Document52 pagesNewly 2hghjsgdNo ratings yet

- General Education Assessment of Grade 12 Stem and Abm Students in Ama University: A Basis To Improve EducationDocument68 pagesGeneral Education Assessment of Grade 12 Stem and Abm Students in Ama University: A Basis To Improve EducationCarlo MagnoNo ratings yet

- Local LiteratureDocument4 pagesLocal LiteratureNelson Paul BandolaNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Brochure - TVET and SkillsDocument7 pagesBangladesh Brochure - TVET and SkillsMusnoon Ansary MoonNo ratings yet

- Background Virtual Confrence Pathway For TVETDocument3 pagesBackground Virtual Confrence Pathway For TVETFemi TokunboNo ratings yet

- Philippine Development Plan, 2017-2022Document15 pagesPhilippine Development Plan, 2017-2022juvelyn e. ismaelNo ratings yet

- Practice and Challenges of Teachers' and Leaders' in Implementing CPD in Primary Schools The Case of Somali Regional State, Fafan Zone EthiopiaDocument13 pagesPractice and Challenges of Teachers' and Leaders' in Implementing CPD in Primary Schools The Case of Somali Regional State, Fafan Zone EthiopiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Literature ReviewDocument10 pagesLiterature Reviewmakawiss1100% (1)

- Education 4 All-Edu3106Document9 pagesEducation 4 All-Edu3106swerlg87ezNo ratings yet

- Towards Achieving EFA Goals by 2015: The Philippine ScenarioDocument9 pagesTowards Achieving EFA Goals by 2015: The Philippine ScenarioTaniacao KC JoyNo ratings yet

- Assessment Schemes in The Senior High School in The Philippine Basic EducationDocument22 pagesAssessment Schemes in The Senior High School in The Philippine Basic EducationNotice MeNo ratings yet

- Transitions to K–12 Education Systems: Experiences from Five Case CountriesFrom EverandTransitions to K–12 Education Systems: Experiences from Five Case CountriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Singh Et. Al. (2010) - Economy Shape Higher EducationDocument12 pagesSingh Et. Al. (2010) - Economy Shape Higher EducationThulasidasan JeewaratinamNo ratings yet

- Sirat (2010) - Strategic Planning DirectionsDocument14 pagesSirat (2010) - Strategic Planning DirectionsThulasidasan JeewaratinamNo ratings yet

- Sheila & Jeffrey (2019) - Private Uni's ContributionsDocument12 pagesSheila & Jeffrey (2019) - Private Uni's ContributionsThulasidasan JeewaratinamNo ratings yet

- Malaysia's 14th GE - Dissecting Malaysian Tsunami - Impacts of Ethinicity and Urban Development On Electoral OutcomesDocument26 pagesMalaysia's 14th GE - Dissecting Malaysian Tsunami - Impacts of Ethinicity and Urban Development On Electoral OutcomesThulasidasan JeewaratinamNo ratings yet

- Hydropower, Development & Poverty Reduction in Laos - Promises Realised or Broken (2020)Document22 pagesHydropower, Development & Poverty Reduction in Laos - Promises Realised or Broken (2020)Thulasidasan JeewaratinamNo ratings yet

- Castle Baking Bun CatalogueDocument6 pagesCastle Baking Bun CatalogueThulasidasan JeewaratinamNo ratings yet

- How Jokowi Won & Democracy Survived - Indonesia's 2014 Elections (Mietzner, M.) (Oct 2014)Document16 pagesHow Jokowi Won & Democracy Survived - Indonesia's 2014 Elections (Mietzner, M.) (Oct 2014)Thulasidasan JeewaratinamNo ratings yet

- Caesar Syria Civilian Protection: "SEC. 7401. SHORT TITLEDocument9 pagesCaesar Syria Civilian Protection: "SEC. 7401. SHORT TITLEThulasidasan JeewaratinamNo ratings yet

- Southeast Asia's Troubling Elections - Nondemocratic Pluralism Indonesia - (Aspinall, E. & Mietzner, M.) (Oct 2019)Document29 pagesSoutheast Asia's Troubling Elections - Nondemocratic Pluralism Indonesia - (Aspinall, E. & Mietzner, M.) (Oct 2019)Thulasidasan JeewaratinamNo ratings yet

- The Democratic Instinct in 21st Century (Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono Keynote Speech - 12 April 2010)Document7 pagesThe Democratic Instinct in 21st Century (Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono Keynote Speech - 12 April 2010)Thulasidasan JeewaratinamNo ratings yet

- Euthenics 1Document18 pagesEuthenics 1penpentjig143No ratings yet

- Information For Applicants 20Document7 pagesInformation For Applicants 20riyad j.mNo ratings yet

- Oladeboye OluwatobiDocument4 pagesOladeboye Oluwatobitobi ayoolaNo ratings yet

- Engl11 Unit 7 Further EducationDocument11 pagesEngl11 Unit 7 Further EducationHuỳnh Cẩm HồngNo ratings yet

- University Calendar For School Year 2020-2021: M T W TH F SDocument2 pagesUniversity Calendar For School Year 2020-2021: M T W TH F SDave SedigoNo ratings yet

- EUTHENICSDocument8 pagesEUTHENICSjohNo ratings yet

- The Sainik School Journey - From Cadet To OfficerDocument3 pagesThe Sainik School Journey - From Cadet To OfficerReeta sharma sharmaNo ratings yet

- New Jamb CBT Exam GuidelinesDocument7 pagesNew Jamb CBT Exam Guidelinestbabashekoni9No ratings yet

- FINAL BHU UET Information Bulletin 2021Document122 pagesFINAL BHU UET Information Bulletin 2021Priyadarshan sharmaNo ratings yet

- Instructions Graduate Application-TLG 2021-2022Document3 pagesInstructions Graduate Application-TLG 2021-2022Basma MaalaNo ratings yet

- AE1130-I Statics TA VacancyDocument1 pageAE1130-I Statics TA VacancyBartłomiej GrochowskiNo ratings yet

- QuestDocument6 pagesQuestPalash BelekarNo ratings yet

- HEC-POLICY FOR STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES AT HEIs IN PAKISTANDocument13 pagesHEC-POLICY FOR STUDENTS WITH DISABILITIES AT HEIs IN PAKISTANMuhammad UmarNo ratings yet

- University of The Philippines Visayas: Admissions - Our.upvisayas@up - Edu.ph Our - Upvisayas@up - Edu.phDocument2 pagesUniversity of The Philippines Visayas: Admissions - Our.upvisayas@up - Edu.ph Our - Upvisayas@up - Edu.phDan JethroNo ratings yet

- Goethe Instuit Online Registration FormDocument1 pageGoethe Instuit Online Registration Formনীল সমুদ্রNo ratings yet

- Nep 2020 FinalDocument31 pagesNep 2020 FinalRiddhi MaheshwariNo ratings yet

- RegionalEnvironmental Economics - Course Guide 2021Document12 pagesRegionalEnvironmental Economics - Course Guide 2021dewangga binzarNo ratings yet

- PadiboDocument2 pagesPadiboAnushka GuptaNo ratings yet

- Attendance & Assessments Notification June 2023Document2 pagesAttendance & Assessments Notification June 2023Dark CamperNo ratings yet

- Volume 3Document152 pagesVolume 3Ayush Gupta100% (1)

- A Closer Look On The Education Systems of Selected Countries of The WorldDocument31 pagesA Closer Look On The Education Systems of Selected Countries of The WorldCM YNo ratings yet

- Application Checklist 1Document1 pageApplication Checklist 1Yuda GestriNo ratings yet

- Application Form NO-818Document4 pagesApplication Form NO-818Mahwash SiddiqNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Maths NSC P2 Answer Book May June 2023 Eng Eastern CapeDocument23 pagesMathematics Maths NSC P2 Answer Book May June 2023 Eng Eastern Cape克莱德No ratings yet

- Dates For ExerciseDocument2 pagesDates For ExercisesyedmazharheroNo ratings yet

- IIMC Entrance Exam 2021: Dates, Merit List (4th Released), Result Check HereDocument16 pagesIIMC Entrance Exam 2021: Dates, Merit List (4th Released), Result Check HerePakhi TewariNo ratings yet

- Aptitude Assessment Procedure - Im BDocument1 pageAptitude Assessment Procedure - Im BZaherNo ratings yet

- Application Form For Jexpo - 2021 Joint Entrance Examination For Admission To Diploma Institutes (Engineering & Technology, Architecture) in West Bengal For The Academic Session 2021-2022Document1 pageApplication Form For Jexpo - 2021 Joint Entrance Examination For Admission To Diploma Institutes (Engineering & Technology, Architecture) in West Bengal For The Academic Session 2021-2022সৌরভ দাসNo ratings yet

- DocScanner 27 Mar 2023 10-05 AmDocument1 pageDocScanner 27 Mar 2023 10-05 AmLight MayNo ratings yet

- 11th & 12 TH Q&ADocument28 pages11th & 12 TH Q&Aankitmohanty01No ratings yet