Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TRANSFORMING EARTH INTO HOUSES - A METHODOLOGY FOR DOCUMENTING CONSTRUCTION PROCESSES AS AN APPRENTICE IN THE IRANIAN DESERT, SOUTH KHORASAN Revised

Uploaded by

Edoardo FerrariOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

TRANSFORMING EARTH INTO HOUSES - A METHODOLOGY FOR DOCUMENTING CONSTRUCTION PROCESSES AS AN APPRENTICE IN THE IRANIAN DESERT, SOUTH KHORASAN Revised

Uploaded by

Edoardo FerrariCopyright:

Available Formats

TRANSFORMING EARTH INTO HOUSES: A METHODOLOGY FOR DOCUMENTING

CONSTRUCTION PROCESSES AS AN APPRENTICE IN THE IRANIAN DESERT,

SOUTH KHORASAN

E. P. Ferrari1

1

Oxford Brookes Univeristy, PhD Student, School of Architecture, Headington Campus

Oxford, OX3 0BP, edoardo.ferrari-2019@brookes.ac.uk

KEY WORDS: Traditional Construction Processes, Apprenticeship, Vernacular Architecture, Anthropology of Architecture,

Documentation Methods, Intangible Heritage, Craft-skills, Video Recordings

ABSTRACT:

In this article is presented a methodology to record and document building processes with an anthropological approach. In the village

of Esfahak, in the region of South Khorasan (Iran), the arid environment, scarce in water and trees, has seen the development of

building forms which are almost entirely made out of earth. Houses had been erected for centuries by local master masons, made

solely of mud bricks and without the use of architectural drawings. This research seeks to document how building processes unfold

and are implemented in the village, for both restoration and new constructions. The researcher is conducting ethnographic fieldwork

on the relationship between villagers and their architecture. This approach is based on participant observation, to study with the local

community how buildings are and were conceived, built, inhabited, maintained and restored. Moreover, the research is employing an

apprentice-style fieldwork method to be able to access building sites. Thus, the researcher learns by doing with masons as a way to

embody the local knowledge, not merely observing the builders. The work on site, given its processual nature, will be documented

employing audio-visual recordings from both an external perspective as well as a first-person one. In this way, by using head-

mounted cameras, it will be possible to re-view building processes together with masons to re-discuss their work. Therefore, using

visual and sensory ethnography in collaboration with research participants, will allow for an in-depth understanding of this craft

practice.

1. INTRODUCTION be beneficial for further research. The researcher's PhD project

investigates vernacular architecture in Central-eastern Iran

1.1 Research Premise taking into account its generative processes, not only

cataloguing or documenting completed material objects. For this

Architecture is among those pan-human activities constituting a purpose is needed a methodology that can consider what

large part of man's material culture. The study of material vernacular architecture studies are generally neglecting, being

objects like buildings includes mostly their cataloguing, listing, limited to representing finished buildings. Thus, it is necessary

and physical documentation -an endeavour complicated mostly to investigate the field with a series of questions in this regard:

by practical issues, e.g. building state of preservation, their how is it possible to study vernacular architectural processes? In

location, and the technologies employed to study them. As which ways are buildings conceived and constructed, knowing

Ingold points out, in the study of material culture there is a that these processes are interconnected to socio-cultural and

tendency to overlook those creative processes which generate historical factors? How can we study those aspects which lead

artefacts, as making vanishes into finished objects (Ingold, to the materialization of a building, but which are themselves

2013:7). Very little is considered when it comes to study the immaterial and cannot be crystallized into an object of study

way buildings come into existence and their construction in which is still in time and place?

specific socio-cultural contexts. Processes are generally

neglected, even though they are necessary aspects needed for 1.3 Research Topic and Literature Review in the Field of

the formation and transformation of the built environment. Vernacular Architecture

Thus, this research is not limited to the analysis of one

particular phase of existence of a finished building, but mostly The study takes into account earthen constructions in South

examines the way architecture is made, in its process, and Khorasan, Iran, precisely in the village of Esfahak. It is

taking into account its creation and transformation (Maudlin, concentrated on the way people tackle local vernacular

Vellinga, 2014). architecture nowadays. The village was selected, among other

reasons, because of the ferment and local involvement with

1.2 Research Questions vernacular construction activities in the area. These initiatives

started from the local community and were not superimposed by

This article presents the researcher's PhD methodology to be institutions, neither by specialized professionals like architects

employed for fieldwork study. This research work is in its first or engineers. Moreover, this area of South Khorasan was never

developmental stage. The main fieldwork phase is yet to be the focus of specialized studies on vernacular architecture

started at the moment of completion of this manuscript. This (Bromberger, 1988; Oliver, 1997; Rahinmia at al., 2013). The

condition allows for the methodological discussion to be kept village is constituted by two settlements: the historical one, and

open for further feedback even during the conduction of a new one that was built beside the former after the 1978 Tabas

fieldwork. It is wished that the methodology outlined here can earthquake. The historical settlement laid abandoned for more

than 30 years before any restoration or construction activity to vernacular buildings. How are master builders working

took place again. A group of young villagers, motivated by nowadays as compared to the past? How are non professionals -

socio-economic reasons, decided to restart working on and in for example villagers or university students who come to the

the old settlement. From 2013, architectural activities have been village to learn hands – approach this craft, and why are they

taken place there, attracting the attention of architects, and willing to learn? What are the reasons convincing old and new

engineers both in and outside Iran, and institutions like the generation builders to work on vernacular buildings today?

Iranian Organization of Cultural Heritage. The researcher took What is the modus operandi of these craftsmen? How are their

part in the first international workshop on vernacular vaulting skills transferred, and how are new learners trying to access this

systems held in the village at the beginning of 2018. One of the form of know-how? How are problems solved on site and in

most interesting aspects of this context was the way people, what ways craftspeople communicate? How are these buildings

including professionals, villagers, craftsmen and even a conceived and 'designed' without plans and how are traditional

foreigner like the researcher, were drawn to the village by its builders confronting with academically trained architects? What

living architectural activities. The 'matter' was not just old ruins is people general interest in these material objects today? These

or material objects from the past, but the engagement of the are questions that require an 'immersion' into people's work and

local community with construction techniques in practice. life. We are trying to get a people's perspective knowing that

Building activities are still taking place nowadays and houses material objects are inextricably interconnected to society and

are not just slowly melting back into the surrounding soil. The culture, and to a given time and place. We are shifting here from

old village is entirely made up of mud brick masonry structures, a single focus on buildings, to questioning the relationship

covered only with mud brick vaults and domes made with no between vernacular architecture and people's work, ideas, skills,

centring, a typical feature of desert Central Iranian architecture and their cultural milieu.

(Wolff, 1966).

1.4 Anthropology and Ethnography of Architecture

The research project is situated in the broader academic

discussion of the anthropology of architecture and making

(Ingold, 2013; Marchand, 2016-2010-2009-2001), taking into

account how people relate to building crafts in a specific

environment. According to Ingold, anthropology is an art of

inquiry, a way to perceive the events of the world to be able to

relate to them and correspond with them (2013, original in

italic). It is not just a way to accumulate notions about the

world, but a way to correlate to it. In this sense we could

compare the accumulation of notions to the mere cataloguing of

buildings, a very useful activity, but which per se is not

Figure 1. The village of Esfahak, South Khorasan complete.

Through anthropological research it is possible to begin

From an architectural perspective it is fascinating to analyse and working with people, not merely on them (Ingold, 2017). The

document these constructions, but also to study the way they are researcher engages with people by carrying out participant

skilfully realized. It is since 2003 with the UNESCO convention observation, committing to understanding a culture and

on intangible cultural heritage that an important shift has been experiencing the world in closer contact with a specific place

made in regard to heritage studies. Inspired by noteworthy and people. The protracted involvement allowed by participant

research on vernacular architecture (see also Correia et al., observation is more than simply a method, more than just

2014; Maudlin, Vellinga, 2014; Noble, 2014), this project tries interviewing research participants, as it is trying to be even

to add on to this corpus by integrating aspects of conception and physically and emotionally in relationship to another

making in architecture. Phenomena linked to practical environment and society. During his master-thesis fieldwork,

experience which unfolds in time. The analysis is concentrated the researcher considered the integration of ethnographic and

on understanding what is behind constructed objects. Studies on anthropological methods into architectural research for the first

architecture and vernacular constructions in Iran, but also time. After a year involvement researching and carrying out

elsewhere, are mostly descriptive in nature (Rainer, 1977; architectural work in India, the researcher had to confront with

Beazley, Harveston, 1982; Hejazi, Saradj, 2014). They tend to several socio-cultural issues that became clear only after many

present a list of characteristics of buildings, their structural, months living in the country. Fostered by his willingness to

technical and spatial features. There is not enough space here to correspond to that environment, the researcher understood how

treat the several articles and thesis which have been written on often a blind focus on material objects (buildings) gives only a

vernacular architecture in Iran in the last ten to fifteen years. It shallow understanding of what it is behind artifacts. With the

has to be pointed out though, that these studies treat almost intention to overcome these limits, the researcher started

exclusively technological aspects of architecture, many of looking at other fields of study, like anthropology and

which praising vernacular forms of technologies. It is ethnography, integrating them with the fields of history and

interesting to discover that one of the most detailed descriptions archaeology. While formulating this research project it was

regarding traditional architectural methods of construction is clear that 'being there' (on site and in a specific environment)

found in the work of Wulff, who included a chapter on and even working with people, is a more suitable attempt at

vernacular construction as part of his seminal work on crafts in accessing intangible aspects of architecture. This is almost

Iran: 'The Traditional Crafts of Persia' (Wulff,1966). It is also uniquely allowed by a long time commitment to working in the

pointed out by Bromberger - an anthropologist who conduced field. With his seminal work on Yemeni masons, Marchand

extensive ethnographic fieldwork in Iran, focussing also on its argues that no studies seriously consider the lives and roles of

vernacular buildings (in the Northern provinces) - that domestic actual builders (Marchand 2001: p. x). In his research, he is the

architecture is generally neglected by scholarly studies (1988). first scholar to combine architectural training and know-how to

From this literature review rise several new questions in regard anthropological research. As stated by Shefold (in Oliver ed.,

1997: 8): 'Vernacular architecture is without architects but not master, he or she becomes a model just by 'being there' (Lave,

without builders.' Mainstream ethnographic and anthropological 2011: 50) - their presence is crucial for the apprentice as well as

studies often overlook stories of individuals and their unique for the researcher. According to Polanyi, there is a large part of

accretion of experience (Marchand, 2010: S3). By engaging in human's knowledge that cannot be told, which is defined as tacit

the craft work of masons, this research is also trying to knowledge (Polanyi, 1966). As this knowledge cannot be

overcome the rigid view that traditional builders are an simply explained verbally, other efforts are needed to its

undistinguished and unchanging group of craftsmen. Thus, how acquisition and eventually, dissemination. Skills and other

to study architecture, craft practices and making processes, forms of tacit knowledge need real life involvement. As stated

combining anthropological and ethnographic methods in by Sillitoe, such knowledge is gained through activities in

architectural research? which it is featured, practically, and its transmission is therefore

dependent on its exposure to action and concrete experience

2. MAIN BODY: A METHODOLOGY FOR THE STUDY (2017: 276). In this research is stressed the importance of

OF VERNACULAR ARCHITECTURE COMBINING AN knowing as the integration of theoretical and practical

ANTHROPOLOGICAL APPROACH knowledge, which are always inseparable elements to be taken

into account (Polanyi, 1958: 7). There is a clear analogy

2.1 Methodology: A Summary between considering different forms of knowledge as necessary

and interconnected at the same time, and the importance to unite

This methodology for data collection includes the interwoven tangible and intangible aspects of architecture. Traditional

application of apprentice-style fieldwork, and the use of audio- craftsmanship is listed by UNESCO among the manifestations

video recordings as one of the main source for data gathering, of intangible cultural heritage as an expression of knowledge

inclusion of research participants, and data analysis. The and skill, as a process of culture. UNESCO stresses the

application of these methods is included as part of the broader importance of safeguarding and encouraging the work of

participant observation approach. Participant observation is a craftsmen and their knowledge transmission, particularly among

key element of anthropological and ethnographic work, but this local communities. The active work of craftsmen is the most

topic is not treated in detail in this article as it would require a important part of this work, consequently the fact that their

longer discussion. In this excursus are only taken into account skills and practice can be taken on by other individuals. It is

apprenticeship and video recordings as methods parts of this important to remember that in building activities, the relevance

larger project frame. of knowledge (often tacit) is far beyond practical building tasks

performed on site, but extends to the selection of materials and

all those operations which surround construction works

(Sillitoe, 2017: 278).

2.3 Becoming an Apprentice: Positive Aspects and

Limitations

The term apprenticeship derives form the latin verb apprĕndĕre,

which means taking, receiving and retaining, thus by extension

learning. The Cambridge Dictionary defines an apprentice as:

“someone who has agreed to work for a skilled person for a

particular period of time and often for low payment, in order to

learn that person's skills.” To be noticed is the stress on the

terms skill and time. Apprenticeship includes several aspects

(Coy, 1989; Downey, Dalidowicz, Mason, 2015; Marchand,

2001-2009; Vankatesan, 2014):

Figure 2. Scheme of the main elements part of the

methodological approach 1. the training of physical craft-skills and technical

know-how and ability to cope with arising errors during

the practice;

2.2 Theoretical background: Issues of Knowledge and 2. the training in managing social relationships linked to

Learning the profession, namely social knowledge;

3. the training and acquisition of specific moral

Knowledge and learning are situated in nature. Knowledge is principles, social values, and paradigms (world views);

not possessed by individuals in finite and static form, but rather 4. and, implicitly in every context, the definition of a

derives from socio-cultural and physical interactions (Marchand social status which is also related to gender and politics.

2007, p 199). Learning is also a situated process, inextricably

linked to any specific environment (Lave, 1988; Lave, 2011). It would be misleading to reduce apprenticeship to just one of

According to Radford, knowledge is a culturally and historically the aspects mentioned above. The learning process of

encoded form of reflecting (2013). Knowledge in this sense can apprentices is an immersive one, as they are totally included

be considered as mere potentiality because not yet instantiated inside it, and they are highly physically engaged with their

(ibid.- original in italic). Thus, actuation is fundamental when working environment (Marchand 2008: 246). Craft-skills and

we talk about knowledge and learning, as what we come to technical know-how related to cultural practices can have a high

know is shaped by and of the same nature of the activity degree of variation, even within the same craft. In the same

through which knowledge is made into an actual form. way, skills learnt during apprenticeship are developed

Learning a craft is connected to practice. It is only through independently from single individuals, and these skills cannot

practice that we can learn how to do something, accessing a be defined as a shared, invariable and uniform code (Downey,

form of knowledge that Ryle defined as know-how (1949). Dalidowicz, Mason 2015). This indicates the uniqueness of any

When we learn together with a more experienced person, a apprentice path.

Positive Aspects: only, in particular outside their working environment, impedes a

The researcher can have a first-person experience by employing deep understanding of a craft. Asking a craftsman about

this methods. In this way one can start to dwell in new physical actions might drastically reduce the amount of data

knowledge while going through a learning process. Marchand gathered. Similarly, observation of the work alone might not

underlines that the apprentice method proved to be more fully explain the subtleties of a specific craft. The importance of

practical in the context of builders' studies, since there was studying with builders lies in their knowledge that operations on

minimum use of verbal explanation in the teaching-learning site seldom go according to a specific plan. Working in a fickle

processes of the builders, as learning is predominantly taking and inconsistent environment, they have to provide constant

place through embodied practices (Marchand, 2001: 175-176). solutions to problems that cannot always be anticipated (Ingold,

Language has several limits when it comes to describing 2013: 48). Through the physical contribution of the researcher is

physical actions and skills. The struggle in explaining physical offered a privileged access to craftsmen's practices and

action in propositional form has been a standing issue for experience, and this is achieved with an exchange of ‘toil’ for

centuries in the West. During the compilation of his ‘ethnographic knowledge’ and craft skill (Marchand, 2008:

Encyclopedia, Diderot found printers and typesetters 2 4 8 ) . This active participation facilitates observation and

inarticulate in explaining what they did, as language can hardly imitation, creating a ‘reciprocity of viewpoints’ and a ‘similar

depict physical action (Sennet, 2008: 179). The issue is not a kinaesthetic experience’ (Jackson in Gieser, 2008: 300).

limit of the craftsmen who are not able to explain what they Learning a craft is inseparably linked to the work environment.

physically do, but in the limits of language when it comes to Considering that learning is situated (Lave, 2011), it is only in a

describe bodily actions. Practicing as an apprentice is a real setting that the researcher can experience not only the

multidimensional experience. Practical activities foster the making, but also its specific cultural and physical environment.

researcher to become bodily and sensually immersed in daily Even when dedicating most of our attention to building

work, allowing for reflection upon their learning, mistakes and processes and skills, we have to remember that apprenticeship is

progress, as well as the difficulties and joys that accompany not merely body-knowledge transfer, nor the acquisition of an

physical labour (Marchand, 2008: 249). Becoming apprentices implicit structure, but a form of shared cultivation of

opens up new channels of communication and expression, increasingly greater skilfulness towards an idealized practice

where practical communication often substitutes verbal one and discipline of errors (Downey, Dalidowicz, Mason 2015:

(Downey, Dalidowicz, Mason 2015). Data collected in this way 185). Becoming an apprentice is an invaluable method to get

are of a unique nature, requiring to be on site, working with access to specific craft-skills, learning environment, social

participants, engaging with the world around us. In a workshop, relationships, and to explore from a specific perspective a given

as well as on a building site, spoken words linked to concrete socio-cultural context in an extended period of time.

examples are more effective than any kind of written directions. Limitations:

In this environment, if any part of the working procedure is not It is not possible as researchers to become an apprentice under

understood, it is possible to immediately ask or even see all aspects considered, as our socio-cultural background and

someone carrying out this task, and a back and forth discussion status drastically modify the way we come to learn a craft.

can initiate (Sennet, 2008: 179). Our senses are also linked to Notwithstanding that apprenticeship can not be reduced to

skill acquisition during apprenticeship. When Grasseni, as an learning a skill, skill acquisition itself is embedded in the larger

ethnographer and visual anthropologist, talks about 'skilled social milieu, where a specific value is attributed to a particular

vision', she underlines the importance of acquiring a specific skill (Vankatesan, 2014: 150). This means that social

skill to be ale to relate to her informants. Working with cattle knowledge related to a skill is linked to specific and localized

breeders in Northern Italy made her realize that learning to look ideas of politics, body gender, and as already stated, by

at her host’s cows was a necessary premise to access their economic factors and status (ibid.). The cultural dimension of

worldview (Grasseni, 2004: 42). knowledge transmission and learning alters and expand the

experience of the practitioner, directly influencing the cognitive

processes ordering our understanding of the world (Sillitoe,

2017: 271). Another limitation to be considered is that of time.

The limited amount of time that a researcher can spend

apprenticing, unlikely guarantees a mastery of the craft, as

Sillitoe points out regarding his work in New Guinea. On the

other hand it is the same Sillitoe admitting that it is through this

form of engaging during participant observation that it was

possible not only to see the limits of this approach, but to get a

certain degree of understanding into the tacit dimension of

knowledge on the building site (2017: 277).

2.4 Recording Processes with Video-cameras: Positive

Aspects and Limitations

Figure 3. Hands-on workshop in Esfahak with Iranian students

Within social sciences, text and written forms of data collection

organized by 'Esfahak Mud Centre', September 2019

have dominated the disciplines even since. In architecture on the

other hand, visuals, mostly comprising technical and

An apprentice style fieldwork method allows to (as mentioned

geometrical drawings, have been the main medium employed

in the definition of apprenticeship): working next to a skilled

for representation. It is argued here that it is only through the

person for a certain period of time. In the context of participant

integration of multiple forms of collection methods,

observation, apprenticeship expands the researcher's

representation and dissemination techniques that a more open-

engagement in terms of time and practice. The researcher is not

ended and inclusive work can be generated. Today, greater

limited to observe, but actively taking part in the learning,

attention to the non-verbal (in particular with the propulsion of

employing his hands-on skills, having also a possibility to make

new technologies) particularly the corporeal, embodied,

mistakes and possibly correcting them. Interviewing craftsmen

sensory, emotional, habitual, pre-cognitive aspects of recordings combined with the active participation in building

subjectivity, can further develop our understanding of the social, activities should reveal more aspects of the work flow and

even in relationship to architecture (Brown, Dilley, Marshall, construction processes. It is in the combination of

2008). It is believed that thought filming with video-cameras apprenticeship and recordings that stands one of the main ways

from different perspectives - and in combination with the help to reflect upon construction which can be extended beyond the

of participants - it will be possible to add new insights into time spend on site. Thus, videos can be employed as a

construction processes. Nevertheless, video cannot be the only participatory tool to engage in discussion with research

forms of data collection, analysis, and dissemination. In this participants after the construction is over. The researcher shares

paragraph are treated the possible ways in which this method the experience with masons on site, so the process is not only

can be creatively employed in combination with apprenticeship, externally observed. Once the construction is over, recordings

as an integrative way to more common research methods. In will be a bridge between the experiences of the participants and

particular when talking about construction, having a visual the researcher. Videos offer the possibility to be re-viewed and

recording of a processes - a time sequence - allows to grasp discussed with participants, and the flow and process of work

several audio-visual elements connected to building techniques can be partly re-experienced together. When we use video as a

and their acquisition. During construction there is a prevalence method, we are not simply recording what people do, to produce

of non-verbal utterances that can be analyzed with the help of visual data for analysis, rather we are taking part in a process of

video recordings. knowledge generation (Pink, 2007: 105). In the process, we also

have a chance to engage with participants in a collaborative

manner. Whether we are interviewing, working with someone

on a building site, or re-viewing videos together with research

participants, another 'dimension' is added to the fieldwork. As a

qualitative method, video often allow for the blurring of

boundaries between visual artifacts and behaviors, becoming as

prominent as the worlds that the subject utters (Shrum, Duque,

Brown 2005: 17). It was with the development of portable

sound sync movie cameras that it was possible for the first time

to use video as an elicitation tool, therefore talking to people

about their actions. showing them a video sequence of their

movements (Harper, 2002: 14). The first experience was a

French movie called Chronique d’un ete (Chronicle of a

Summer), filmed in Paris by visual anthropologist Jean Rouch

Figure 3. Excerpt of a video of a master builder in the process of and sociologist Edgar Morin in the 1950s.

constructing a barrel vault without centring, Esfahak, September Videos will be recorded from different perspectives. A fixed

2019 camera on tripod will record building processes as an 'external

viewer'. The researcher will have a head-mounted camera to

Positive Aspects: review his own work on site in collaboration and interaction

Observation is a crucial element of learning processes, in with master builders. A third camera will be recording the

particular for crafts. According to neurologist Marc Jannerod, master builder perspective, and this will be achieved with a self-

the observation of someone engaged in practice acts upon our wearable head-mounted camera providing an insider first-

motor-based understanding of that action. He explains that person point of view. Using diverse observational perspectives

vision can process images of bodily movement and activity, will allow to include research participants in further discussion,

which then serve as inputs to the motor domains of our and strengthen the researcher's understanding of the dynamic

cognition. These images are distinguished into constituent interplay of construction activities. Thus, a sort of 'expanded

postures and movements that are assigned a motor-based apprenticeship' is virtually created once construction is over, by

interpretation (Jannerod 1994 in Marchand, 2008: 263-26). combining video re-play with interviewing masons. Re-playing

Similarly, video images also have a high potential for capturing (which will likely include unexpected events) gives the

processes and actions that record the patterns of life and researcher multiple possibility to triangulate data. At the same

movement (Tim Dants in Pink, 2007: 103). The use of video in time, many actions gone unnoticed during the process can be

social science, and in particular ethnography and anthropology, seen later, providing fresh material for more debate and

has been increasingly taken up by researchers (Carrol, Mesam analysis.

2018; Jarret, Liu 2018; Lahlou, Le Bellu, Boesen-Mariani 2015; Moreover, self-wearable cameras, commonly available on the

S.Lahlou 2010-2011; Le Bellu 2016; Murthy 2008; Pink, market, are a relatively inexpensive mean to record in high

Sumartojo, Lupton, et al. 2017; Pink 2015-2008-2007; Shrum, quality for a researcher operating alone. They are easy to handle

Duque Ynalvez 2007; Shrum, Duque, Brown 2005; Yang, and can be adapted to working on site since they are resistant

2015). Studies range from the fields of psychology to cognitive and designed for outdoor use. Being user friendly means that

science. Video, as compared to other visuals methods, adds the even research participant can operate them if and when needed.

dimension of time and sound. The flow of life captured with a No cables are needed which would impede normal procedures

video-camera, especially when taking part to craft processes, to be carried normally on a building site. Their light weight

may be compared to informal interviews which have not been facilitates wearing them for protracted periods of time.

planned ahead. Video ethnography is a method which can be

much inductive in nature, leaving the possibility to unexpected

events to manifest. A common problem which scholars

associated with everyday life and processes is that of not being

able to access its ‘flow', unless trying to slice it into a

representational form - crystallized and objectified for analysis

(Pink et al., 2017: 377). These issues cannot be solved simply

by utilizing video-ethnography. However, the use of video

Figure 4. Excerpt of a video recorded with head-mounted

camera from the builder's perspective, Esfahak, September 2019

Limitations:

Acknowledging the advantages of digital video recording, we

also have to be careful to always remind that the work of

researchers should not be only linked to technological

advancements and their socially and locally bounded limits. Part

of the kit of a researcher (architect-cum-anthropologist-cum-

ethnographer) should be different methods, all more or less

suitable to the specific circumstance in which the researcher is

working. It is not always possible to record with a video

camera. Video recordings will necessarily have to be focused on

specific parts of the construction as it will be unlikely to record

all phases of the building process. This is due to obvious

practical limits given by the impossibility to always set up

cameras during the working day on site. It is also due to the Figure 5. Scheme representing the key features of the 'Expanded

amount of data recorded, as an over production of data Apprenticeship' process

(excessive recording hours) will not allow for better analysis -

on the contrary it can impede a smooth workflow. This implies

that a careful selection of those relevant moments of

construction, important also in terms of documentation, will

have to be selected and agreed upon ahead. For example in the

case of South Khorasan and this project, it will be important to

record the construction of vaults and domes without wooden

centring, being one of the most unique features of local

buildings. The use of a head-mounted self wearable camera is

surely less sophisticated than customized cameras developed on

purpose for each study, similarly to those employed for Self-

Evidence-Based-Ethnography, SEBE, developed by Lahlou at

the LSE (see Lahlou, 2010, 2011; Lahlou, Le Bellu, Boesen-

Mariani, 2015). Nevertheless, this study is not a psychologically

oriented research, thus there is no necessity of wearing a

customized eye level camera. Lahlou in the first place states that

the most important element of a method, including SEBE, is

building trust with the informants, apart from the practicalities

concerning devices, as methods are primarily needed to create a

good environment for the research to be carried out (Lahlou,

2011: 624).

Figure 6. Scheme of the possibilities offered by this

methodology regarding data analysis and triangulation

3. CONCLUSIONS with other disciplines and methods. At this stage are presented

more questions than solutions and it will be interesting to see

The study of vernacular architecture is often limited to finished where this conversation might lead other researchers of

objects and what happens to them once they are embedded in vernacular architecture.

social life. These finished objects are the tangible

manifestations of a culture, an architecture of a place and ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

people. In documenting these buildings it is important to also

understand and study the processes behind them. These The author would like to thank the villagers and craftsmen of

processes are necessary for the materialization of these Esfahak for their kind welcome to the village, allowing access

buildings, and essential to instantiate their local meaning and to their activities. He is also grateful to the team of 'Esfahak

their transformation through time. Processes of conception and Mud Centre', professionals and volunteer students alike, for

making become manifest as building techniques, craft-skills, letting him take part in the workshops organized. The author is

ways of learning and of problem solving which are intangible recipient of ISA Trust Travel Grant 2019 and the British

aspects of architecture - often unnoticed or overlooked when we Institute of Persian Studies Travel Grant April 2019 which

only take into account the materiality of buildings. For this helped him facilitate travels to the village and ponder upon this

reason rise the question: how does the process of building methodology.

making unfolds, and in which way? To answer these questions,

looking in particular at vernacular architecture, a methodology REFERENCES

is proposed based on the combination of anthropology and

architectural research methods. This methodology is based on Beazley, E., Harverson, M. 1982: Living with the Desert:

spending protracted periods of time among local builders and Working Buildings of the Iranian Plateau. Aris & Phillips Ltd,

people (participant observation) integrated with the direct Warminster

engagement of the researcher in construction activities

(apprenticeship). Given the importance of vision and mimicry Bromberger, C. 1988. Banna'i', in Encyclopaedia Iranica

as part of craft-skills learning, the researcher will also recur to Online. http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bannai-

video recordings to supplement his research tool kit. Recordings construction (22 February 2019)

will allow for an 'expanded apprenticeship' experience even Correia, M., Di Pasquale, F., Mecca, S. (eds.) 2014: Versus:

after the work on site is over. This gives the researcher more Heritage for Tomorrow, Vernacular Knowledge for Sustainable

opportunities to triangulate data and to figure out aspects of the Future, FUP, Firenze

work that might otherwise go unnoticed. Apprenticeship will

allow the researcher to be physically engaged with work, Coy, M. W. (ed.) 1989: Apprenticeship: From Theory to

experiencing the process in first-person and hands-on, Method and Back Again. State University of New York Press,

reinforcing data triangulation for analysis. On the other hand we Albany

have to take into account implicit limitations of this approach. It Downey, G., Dalidowicz, M., Mason, P. H. 2015.

is important to know that the use of video-cameras always Apprenticeship as Method: Embodied Learning in Ethnographic

depends on the particular conditions created on site, social practice', Qualitative Research, 15 (2), 183–200. doi:

relationship and ease to manoeuvre the equipment. It has to be 10.1177/1468794114543400

constantly evaluated when it is correct to employ video to also

avoid an over accumulation of data that are not likely to be Gieser, T. 2008. Embodiment, Emotion and Empathy: A

analysed. During the development of a PhD thesis, time is Phenomenological Approach to Apprenticeship Learning,

unlikely to be enough to go through a comprehensive process of Anthropological Theory, 8 ( 3 ) , 2 9 9 - 3 1 8 . d o i :

learning, which generally requires several years of 10.1177/1463499608093816

apprenticeship. Thus, time is amongst the most relevant

limitations for this kind of research. Socio-cultural factors have Grasseni, C. 2004. Skilled vision: An apprenticeship in

to be also taken into account, as the researcher needs to Breeding Aesthetics, Social Anthropology, 12 (1), 41–55. doi:

acknowledge its different social status, which often drastically 0.1017/S0964028204000035

differ from that of participants.

Kresse, K., Marchand T.H.J. 2009. Introduction: Knowledge in

Culture encompasses lived activities that individuals engage in

Practice,A f r i c a ,79 (1), 1-16. doi:

as part of their daily life as much as on a building site.

10.3366/E0001972008000570

Interactions and experiences in specific environments are

crucial for acquiring skills and for experiencing the gradual Harper, D. 2002. Talking about pictures: a case for photo

transition from unexperienced to experienced builder (Sillitoe, elicitation, V i s u a l S t u d i e s , 1 7 ( 1 ) , 1 3 - 2 6 . d o i :

2017: 225). This active work, socio-culturally and historically 10.1080/14725860220137345

tied, gives the researcher a closer point of view to that of the

makers. In particular when we take into account vernacular Hejazi, M., Saradj, F. M. 2014: Persian Architectural Heritage:

architecture, we often see buildings constructed without plan Architecture. WIT Press, Southampton & Boston

drawings, but greatly developed and adapted during the

construction activity. It is by trying to enter these building Ingold, T. 2017. Anthropology Contra Ethnography, HAU:

processes, attempting to learn specific craft-skills and engaging Journal of Ethnographic Theory, 1 (7), 21-26. doi:

in the making with builders (and their society), than an http://dx.doi.org/10.14318/hau7.1.005

expanded perspective can be sought on vernacular buildings. Ingold, T. 2013: Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and

The documentation and study of vernacular architecture Architecture. Routledge, Abingdon

necessitates a deeper involvement with work on site in

relationship to makers. These initial methodological thoughts Lahlou, S., Le Bellu, S., Boesen-Mariani, S. 2015. Subjective

are set here as a test to research limits on what can be further Evidence Based Ethnography: Method and Applications,

analysed as part of vernacular architecture studies and Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 49, 216-238.

documentation. This is possible through a dynamic conversation doi: 10.1007/s12124-014-9288-9

Lahlou, S. 2011. How can we capture the subject’s perspective? Ryle, G. 1949: The Concept of Mind. Hutchinson, London

An evidence-based approach for the social scientist, Social

S c i e n c e I n f o r m a t i o n, 50 (3–4), 607–65. Sennet, R. 2008: The Craftsman. Allen Lane-Penguin Books,

doi:10.1177/0539018411411033 London

Lahlou, S. 2010. Digitization and transmission of human Shrum, W., Duque, R., Ynalvez, M. 2007. Lessons of the Lower

experience, Social Science Information, 49 (3), 291–327. doi: Ninth: Methodology and Epistemology of Video Ethnography,

10.1177/0539018410372020 T e c h n o l o g y i n S o c i e ty , 2 9 , 2 1 5 – 2 2 5 . d o i :

10.1016/j.techsoc.2007.01.009

Lave, J. 2011: Apprenticeship in Critical Ethnographic

Practice. University of Chicago Press Shrum, W., Duque, R., & Brown, T. 2005. Digital Video as

Research Practice: Methodology for the Millennium, Journal of

Lave, J. 1988: Cognition in Practice. Cambridge University

Research Practice, 1 (1), Article M4, 1-19. Available at:

Press

http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/6/11 (19 August

Le Bellu, S. 2016. Learning the Secrets of the Craft Through the 2019)

Real-Time Experience of Experts: Capturing and Transferring

Sillitoe, P. 2017: Built in Niugini: Constructions in the

Exp e r t s ’ T a c i t K now l e dg e t o No vi c e s , Perspectives

Highlands of Papua New Guinea. The RAI Series, Sean

interdisciplinaires sur le travail et la sante [Online], 18 (1), 1-

Kingston Publishing, Canon Pyon

33. doi : 10.4000/pistes.4685

Suess, E. 2014. Doors Don't Slam: Time-Based Architectural

Marchand, T.H.J. (ed.) 2016: Craftwork as Problem Solving:

Representation, in Maudlin, D., Vellinga, M. (eds.) (2014)

Ethnographic Studies of Design and Making. Ashgate

Consuming Architecture: On the Occupation, Appropriation

Publishing, Farnham

and Interpretation of Buildings. Abingdon: Routledge, 243-259

Marchand, T.H.J. (ed.) 2010: Making knowledge: explorations

Vankatesan, S. 2014. Learning to Weave; Weaving to Learn...

of the indissoluble relation between minds, bodies, and

What?, in Marchand, T.H.J. (ed.) (2010) Making knowledge:

environment. Vol.16 Special Issue. Royal Anthropological

explorations of the indissoluble relation between minds, bodies,

Institute of Great Britain & Ireland

and environment. Vol.16 Special Issue. Royal Anthropological

Marchand, T.H.J. 2009: The Masons of Djenne. Indiana Institute of Great Britain & Ireland, 150-166

University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis

Wulff, H. E. 1966: Traditional Crafts of Persia. MIT Press

Marchand, T.H.J. 2008. Muscles, Morals and Mind: Craft

Yang, K. 2015. Participant Reflexivity in Community-Based

Apprenticeship and the Formation of Person', British Journal of

Participatory Research: Insights from Reflexive Interview,

Educational Studies, 56 (3), 245-271. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-

Dialogical Narrative Analysis, and Video Ethnography, Journal

8527.2008.00407.x

of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 25, 447–458. doi:

Marchand, T.H.J. 2007. Crafting Knowledge: The Role of 10.1002/casp.2227

'Parsing and Production' in the Communication of Skill-

BasedKnowledge Among Masons. In Harris, M. (ed.) Ways of

Knowing: Anthropological Approaches to Crafting Experience

and Knowledge. New York Oxford: Berghahn Books, 181-199

Marchand, T.H.J. 2001. Minaret Building and Apprenticeship

in Yemen. Routledge, Abingdon

Ma udl i n, D. , Ve l l i nga , M. (eds. ) 2014: Consuming

Architecture: On the Occupation, Appropriation and

Interpretation of Buildings. Routledge, Abingdon

Noble, A. G. 2014: Vernacular Buildings: A Global Survey, IB

Tauris, London

Oliver, P. (ed.) 1997: Encyclopedia of Vernacular Architecture

in the World vol. 1. Cambridge University Press

Pink, S., Sumartojo, S., Lupton, D., Labond, C. H. 2017.

Empathetic technologies: digital materiality and video

ethnography, V i s u a l S t u d i e s , 32 (4), 371–381. doi:

10.1080/1472586X.2017.1396192

Pink, S. 2007: Doing Visual Ethnography: Images, Media and

Representation in Research. 2nd edn. Sage, London

Polanyi, M. 1966: The Tacit Dimension. Doubleday, New York

Rahinmia, R. et al. 2013. Bazshenakht-e Tajrobiat-e Me’mari-e

Bumi dar Jonub-e Khorasan, Jahat-e Hefazat va Maremmat-e

Me’mari-e Kheshti, Maskan va Mohit-e Rusta, 142, 19-32

(Persian)

Rainer, R. 1977: Anonymes Bauen im Iran. Akademische

Druck, Graz

You might also like

- Architecture in Northern Ghana: A Study of Forms and FunctionsFrom EverandArchitecture in Northern Ghana: A Study of Forms and FunctionsNo ratings yet

- The Viability of Integrating Green and Vernacular Architecture in The Tourism Development of Donsol, SorsogonDocument33 pagesThe Viability of Integrating Green and Vernacular Architecture in The Tourism Development of Donsol, SorsogonVinson Pacheco Serrano0% (1)

- Investigating The Level of Responsiveness of Vernacular Architecture To The Needs of Citizens in Sari, IranDocument13 pagesInvestigating The Level of Responsiveness of Vernacular Architecture To The Needs of Citizens in Sari, IranHarshita BhanawatNo ratings yet

- Strong Architectonic Elements of Traditional Vernacular Architecture in IndonesiaDocument8 pagesStrong Architectonic Elements of Traditional Vernacular Architecture in Indonesiafabrian baharNo ratings yet

- Identity in Igbo Architecture - A Case Study of The Ekwuru in Okija and The Obi in NimoDocument65 pagesIdentity in Igbo Architecture - A Case Study of The Ekwuru in Okija and The Obi in NimoIbeanusi Nonsoo67% (3)

- Analysis of The Contextual Architecture and Its Effect On The Structure of The Residential Places in Dardasht Neighborhood of IsfahanDocument11 pagesAnalysis of The Contextual Architecture and Its Effect On The Structure of The Residential Places in Dardasht Neighborhood of IsfahanAndrijaNo ratings yet

- CWE Vol10 SPL (1) P 448-458Document11 pagesCWE Vol10 SPL (1) P 448-458M Hammad ManzoorNo ratings yet

- Philosophy and Theory of Vernacular Arch PDFDocument13 pagesPhilosophy and Theory of Vernacular Arch PDFpatrick racionalistaNo ratings yet

- Modern Lokal4Document17 pagesModern Lokal4ciciofadhil naufalNo ratings yet

- Architectural Museum and Art GalleryDocument7 pagesArchitectural Museum and Art GallerytanujaNo ratings yet

- Mapping Historic Urban Landscape Layers in Kota Lama SemarangDocument17 pagesMapping Historic Urban Landscape Layers in Kota Lama SemarangSumaiya SrityNo ratings yet

- Akulturasi Arsitektur Lokal Dan Non Lokal Pada Aspek Tatanan Lahan Dan Aspek Bangunan Pada Gedung Perpustakaan Bank Indonesia Di Surabaya Dan Museum Sumpah Pemuda Di JakartaDocument14 pagesAkulturasi Arsitektur Lokal Dan Non Lokal Pada Aspek Tatanan Lahan Dan Aspek Bangunan Pada Gedung Perpustakaan Bank Indonesia Di Surabaya Dan Museum Sumpah Pemuda Di Jakartaalya ayu ristyawatiNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Education and Research Vol. 3 No. 6 June 2015Document10 pagesInternational Journal of Education and Research Vol. 3 No. 6 June 2015Muhammad RedoNo ratings yet

- The Cooperation of Well-Known Architects, Architecture Students and Local Communities in The Process of Architectural Creation in Different Cultural Environments. Examples From AsiaDocument18 pagesThe Cooperation of Well-Known Architects, Architecture Students and Local Communities in The Process of Architectural Creation in Different Cultural Environments. Examples From AsiaAnna Rynkowska-SachseNo ratings yet

- Introduction (Landscape and Architecture) : Journal of Architectural Education February 2004Document4 pagesIntroduction (Landscape and Architecture) : Journal of Architectural Education February 2004ShreyaNo ratings yet

- Considering Afrocentrism in Hausa Traditional ArchitectureDocument6 pagesConsidering Afrocentrism in Hausa Traditional ArchitectureInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Gilan)Document15 pagesGilan)barbaradanaenNo ratings yet

- Akulturasi Arsitektur Lokal Dan Modern Pada Bangunan P-House, SalatigaDocument12 pagesAkulturasi Arsitektur Lokal Dan Modern Pada Bangunan P-House, SalatigaN. Alyssa Rylie VermilliaNo ratings yet

- Yussupova Et Al - Ornamental Art and Symbolism OADocument22 pagesYussupova Et Al - Ornamental Art and Symbolism OASangeetha MNo ratings yet

- Sitem BangunanDocument8 pagesSitem BangunanFerdi SaputraNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument11 pages1 PBAlvin ZeyerNo ratings yet

- History of Architecture Iii: (Written Report)Document16 pagesHistory of Architecture Iii: (Written Report)Rod NajarroNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Current Life Sciences: Issn: Louis Kahn Position in Sustainable ArchitectureDocument9 pagesInternational Journal of Current Life Sciences: Issn: Louis Kahn Position in Sustainable ArchitectureHuda's WorldNo ratings yet

- Uas BitDocument2 pagesUas BitFredrik M4t4No ratings yet

- Habitus? The Social Dimension of Technology and Transformation - AnDocument11 pagesHabitus? The Social Dimension of Technology and Transformation - AnClaudio Wande LópezNo ratings yet

- Learn from the past: Malay vernacular architecture's lessons for contemporary designDocument6 pagesLearn from the past: Malay vernacular architecture's lessons for contemporary designNurul syara ainaa RahimNo ratings yet

- FullPaper SEATUC PDFDocument6 pagesFullPaper SEATUC PDFNurul syara ainaa RahimNo ratings yet

- Re-Reading Iranian Vernacular Architecture From A New PerspectiveDocument16 pagesRe-Reading Iranian Vernacular Architecture From A New PerspectivehabNo ratings yet

- Traditional Dwellings: An Architectural Anthropological Study From The Walled City of LahoreDocument7 pagesTraditional Dwellings: An Architectural Anthropological Study From The Walled City of LahoreAzka Gul ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- 02 - Heritage Resources As A MethodDocument8 pages02 - Heritage Resources As A MethodIEREKPRESSNo ratings yet

- Louis Kahn Position in Sustainable Architecture: August 2014Document10 pagesLouis Kahn Position in Sustainable Architecture: August 2014Mae PuyodNo ratings yet

- Modern Lokal 3Document8 pagesModern Lokal 3ciciofadhil naufalNo ratings yet

- 15. Un estudio tipológico, ambiental y sociocultural de los espacios semiabiertos en el Mediterráneo Orientalvernáculo arquitectura El caso de ChipreDocument19 pages15. Un estudio tipológico, ambiental y sociocultural de los espacios semiabiertos en el Mediterráneo Orientalvernáculo arquitectura El caso de Chiprekatia.flor28No ratings yet

- History and Transformation of Interior Design in IDocument10 pagesHistory and Transformation of Interior Design in ISHALAKANo ratings yet

- 9 Priya Joseph - Paper For Research TrendDocument5 pages9 Priya Joseph - Paper For Research TrendArchana M NairNo ratings yet

- The Architecture of Bat Trang Pottery VillageDocument13 pagesThe Architecture of Bat Trang Pottery VillagevvaNo ratings yet

- 1-s2.0-S1877042815062576-mainDocument10 pages1-s2.0-S1877042815062576-mainMoeez AhmadNo ratings yet

- Senanayake SasmDocument4 pagesSenanayake SasmsanchaneesenanayakeNo ratings yet

- Scientific African: Gali Kabir Umar, Danjuma Abdu Yusuf, Abubakar Ahmed, Abdullahi M. UsmanDocument8 pagesScientific African: Gali Kabir Umar, Danjuma Abdu Yusuf, Abubakar Ahmed, Abdullahi M. UsmanNafila AdrianaNo ratings yet

- 2 PBDocument9 pages2 PBHasliana RustamNo ratings yet

- Regionalism in Architecture PDFDocument12 pagesRegionalism in Architecture PDFVedika Agrawal86% (21)

- Transforming Local Architecture for the Modern EraDocument21 pagesTransforming Local Architecture for the Modern EraHarshita BhanawatNo ratings yet

- Studi Proses Tradisi Membangun Rumah Tinggal Gorontalo Terhadap Kebudayaan GorontaloDocument12 pagesStudi Proses Tradisi Membangun Rumah Tinggal Gorontalo Terhadap Kebudayaan GorontaloSardi PatutiNo ratings yet

- City Identity Reflected in Art Craft School Student Projects at Sour Magra El Oyoun in CairoDocument15 pagesCity Identity Reflected in Art Craft School Student Projects at Sour Magra El Oyoun in CairoIEREKPRESSNo ratings yet

- In Uence of Socio-Cultural Factors On The Formation of Architectural Spaces (Case Study: Historical Residential Houses in Iran)Document12 pagesIn Uence of Socio-Cultural Factors On The Formation of Architectural Spaces (Case Study: Historical Residential Houses in Iran)Siblings OnBoardNo ratings yet

- Skaza 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 471 022033Document8 pagesSkaza 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 471 022033Disha ModekarNo ratings yet

- How Perception Shapes ArchitectureDocument8 pagesHow Perception Shapes ArchitectureDisha ModekarNo ratings yet

- Skaza 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 471 022033Document8 pagesSkaza 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 471 022033Disha ModekarNo ratings yet

- Pitch Presentation StructureDocument11 pagesPitch Presentation StructuremariyaNo ratings yet

- Adaptive Reuse To MuseumDocument13 pagesAdaptive Reuse To MuseumJohn Edenson VelonoNo ratings yet

- Cubic Architecture and Modern Residential Architecture in Turkey and Iran (1930sDocument16 pagesCubic Architecture and Modern Residential Architecture in Turkey and Iran (1930sSally AlaslamiNo ratings yet

- 1764 - Shrutkirti SupekarDocument16 pages1764 - Shrutkirti SupekarShrutkirti SupekarNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Va - NotesDocument6 pagesUnit 2 Va - NotesAmuthenNo ratings yet

- Place Making ValuesDocument13 pagesPlace Making ValueszahraNo ratings yet

- Residents' Sense of Place in Semarang ChinatownDocument12 pagesResidents' Sense of Place in Semarang ChinatownAnnisa Magfirah RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Dehatt: Juhani Katainen & Seppo AuraDocument5 pagesDehatt: Juhani Katainen & Seppo AuraahceratiNo ratings yet

- Lecture 002 Unit 2 2018 Prof SivaramanDocument14 pagesLecture 002 Unit 2 2018 Prof Sivaramansiva ramanNo ratings yet

- Regeneration of Decaying Urban Place Through Adaptive Design InfillDocument45 pagesRegeneration of Decaying Urban Place Through Adaptive Design InfillHafiz AmirrolNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Modern Dutch Colonial ArchitectureDocument7 pagesThe Concept of Modern Dutch Colonial ArchitectureAliaa Ahmed ShemariNo ratings yet

- The Transformation of Aesthetics in Architecture From Traditional To Modern Architecture: A Case Study of The Yoruba (Southwestern) Region of NigeriaDocument10 pagesThe Transformation of Aesthetics in Architecture From Traditional To Modern Architecture: A Case Study of The Yoruba (Southwestern) Region of NigeriaJournal of Contemporary Urban AffairsNo ratings yet

- Samsung C&T AuditDocument104 pagesSamsung C&T AuditkevalNo ratings yet

- Engineers Guide To Microchip 2018Document36 pagesEngineers Guide To Microchip 2018mulleraf100% (1)

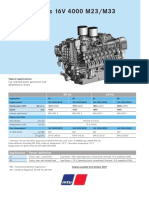

- Diesel Engines 16V 4000 M23/M33: 50 HZ 60 HZDocument2 pagesDiesel Engines 16V 4000 M23/M33: 50 HZ 60 HZAlberto100% (1)

- Petroleum Research: Khalil Shahbazi, Amir Hossein Zarei, Alireza Shahbazi, Abbas Ayatizadeh TanhaDocument15 pagesPetroleum Research: Khalil Shahbazi, Amir Hossein Zarei, Alireza Shahbazi, Abbas Ayatizadeh TanhaLibya TripoliNo ratings yet

- Macroeconomics QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesMacroeconomics Questionnairevikrant vardhanNo ratings yet

- What Is ReligionDocument15 pagesWhat Is ReligionMary Glou Melo PadilloNo ratings yet

- NCP GeriaDocument6 pagesNCP GeriaKeanu ArcillaNo ratings yet

- Perlman Janice, The Myth of Marginality RevisitDocument36 pagesPerlman Janice, The Myth of Marginality RevisitLuisa F. RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Marine Clastic Reservoir Examples and Analogues (Cant 1993) PDFDocument321 pagesMarine Clastic Reservoir Examples and Analogues (Cant 1993) PDFAlberto MysterioNo ratings yet

- 2013 KTM 350 EXC Shop-Repair ManualDocument310 pages2013 KTM 350 EXC Shop-Repair ManualTre100% (7)

- MgstreamDocument2 pagesMgstreamSaiful ManalaoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Context CluesDocument33 pagesLesson 1 Context CluesRomnick BistayanNo ratings yet

- Common Expressions in Business 2Document2 pagesCommon Expressions in Business 2abdeljelil manelNo ratings yet

- ACCT250-Auditing Course OutlineDocument7 pagesACCT250-Auditing Course OutlineammadNo ratings yet

- GES1003 AY1819 CLS Tutorial 1Document4 pagesGES1003 AY1819 CLS Tutorial 1AshwinNo ratings yet

- Teresita Dio Versus STDocument2 pagesTeresita Dio Versus STmwaike100% (1)

- Bread and Pastry Production NC II 1st Edition 2016Document454 pagesBread and Pastry Production NC II 1st Edition 2016Brian Jade CadizNo ratings yet

- Bradley Et Al. 1999. Goal-Setting in Clinical MedicineDocument12 pagesBradley Et Al. 1999. Goal-Setting in Clinical MedicineFelipe Sebastián Ramírez JaraNo ratings yet

- National Geographic USA - 01 2019Document145 pagesNational Geographic USA - 01 2019Minh ThuNo ratings yet

- OUM Human Anatomy Final Exam QuestionsDocument5 pagesOUM Human Anatomy Final Exam QuestionsAnandNo ratings yet

- Create Sales Order (Bapi - Salesorder - Createfromdat2) With Bapi Extension2Document5 pagesCreate Sales Order (Bapi - Salesorder - Createfromdat2) With Bapi Extension2raky03690% (1)

- Maximizing ROI Through RetentionDocument23 pagesMaximizing ROI Through RetentionSorted CentralNo ratings yet

- Json Cache 1Document5 pagesJson Cache 1Emmanuel AmoahNo ratings yet

- CAPITAL ALLOWANCE - Exercise 3 (May2021)Document2 pagesCAPITAL ALLOWANCE - Exercise 3 (May2021)NORHAYATI SULAIMANNo ratings yet

- Fishblade RPGDocument1 pageFishblade RPGthe_doom_dudeNo ratings yet

- Villariba - Document Analysis - Jose RizalDocument2 pagesVillariba - Document Analysis - Jose RizalkrishaNo ratings yet

- l3 Immunization & Cold ChainDocument53 pagesl3 Immunization & Cold ChainNur AinaaNo ratings yet

- Science in VedasDocument42 pagesScience in VedasPratyush NahakNo ratings yet

- Arts, Sciences& Technology University in Lebanon: Clinical Booking WebsiteDocument25 pagesArts, Sciences& Technology University in Lebanon: Clinical Booking WebsiteTony SawmaNo ratings yet

- First Communion Liturgy: Bread Broken and SharedDocument11 pagesFirst Communion Liturgy: Bread Broken and SharedRomayne Brillantes100% (1)