Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Definingandmeasuring

Uploaded by

StancuOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Definingandmeasuring

Uploaded by

StancuCopyright:

Available Formats

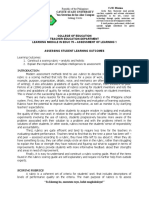

Defining and Measuring Creativity:

Are Creativity Tests Worth Using?

Arthur J. Cropley Semantic Scale, which is based on three dimensions: Novelty

(the product is original, surprising and germinal), Resolution

(the product is valuable, logical, useful, and understandable),

and Elaboration and Synthesis (the product is organic, elegant,

Creativity tests measure specific cognitive processes such as thinking

divergently, making associations, constructing and combining broad

complex, and well-crafted). These dimensions are assessed by

categories, or working on many ideas simultaneously. They also mea- raters using a semantic-differential rating scale (e.g., surpris-

sure noncognitive aspects of creativity such as motivation (e.g., ing-unsurprising, logical-illogical, or elegant-inelegant) with

impulse expression, desire for novelty, risk-taking), and facilitatory per- 43 items in the latest version (Besemer & O'Quin, 1999).

sonal properties like flexibility, tolerance for independence, or positive

attitudes to differentness. Raters can score the various kinds of test

Besemer (1998) confirmed empirically that the scale measures

with substantial levels of agreement, while scores are internally stable three dimensions, and confirmed its ability to distinguish con-

to an acceptable degree. The tests also correlate to a reasonable sistently among products (three chairs of quite different

degree with various criteria of creativity such as teacher ratings, and design). Reliabilities of the three dimensions ranged from 0.69

are useful predictors of adult behavior. Thus, they are useful in both

research and education. However, they are best thought of as mea-

to 0.87 (alpha coefficients), with the majority of coefficients

sures of creative potential because creative achievement depends on being in excess of .80.

additional factors not measured by creativity tests, such as technical r

t seems logical to use expert opinion in rating products,

E

Downloaded by [Western Kentucky University] at 03:55 03 May 2013

skill, knowledge of a field, mental health, or even opportunity. However,

the multidimensional creativity concept they define indicates that Land Hennessey (1994) emphasized the method of con-

assessments should be based on several tests, rather than relying on a sensual assessment. However, she reported inter-rater agree-

single score. ment ranging up to .93 even among untrained undergraduates

who rated geometric designs or Picasso drawings on Creativi-

ty of Product and Creativity of Process on a 7-point scale,

Arthur J. Cropley is the author of 20 books and many articles and

simply applying their own subjective understanding of these

received the 1997 Creativity Award of the World Council for Gifted and qualities. Internal reliabilities of the ratings of creativity

Talented Children. He taught school in Australia, England and Canada. ranged from .73 to .93. Other studies also suggest that judging

After graduate study in Canada he taught in universities in Australia, properties connected with the creativity of products such as

Canada and Germany until retiring in 1998. effectiveness, usefulness, complexity, or understandability is

not as difficult as might be supposed. Vosburg (1998) report-

ed that untrained judges who rated products on 7-point scales

such as Very complex — Not at all complex or Very under-

K altsounis and Honeywell (e.g., 1980) published a sub-

stantial list of creativity tests, and Torrance and Goff

(1989) identified no fewer than 255 such instruments.

standable — Not at all understandable achieved inter-rater

reliabilities of about .90.

Although there is obviously no shortage of tests, many review-

ers have questioned their usefulness, usually on the grounds of

technical shortcomings, although they do not dismiss them out The Creative Process

of hand (Hocevar, 1981; Hocevar & Bachelor, 1989; Cooper,

1991). This article examines a few of the tests, emphasizing Creative thinking

the contents they measure and the consistency with which they The Creativity Tests for Children is based on Guilford's

measure them. The number of tests in existence made it neces- (1976) Structure of Intellect (SI) model of intelligence. Suit-

sary to restrict coverage to instruments specifically referring to able for Grades 4-6, it involves 10 tests from either the seman-

creativity that were developed during the modern creativity era tic (verbal) or the visual and figural (nonverbal) content areas

introduced by Guilford (1950). The review is also restricted to of the SI model. The tests focus on "divergent production" of

paper-and-pencil tests because these are most widely used in units, classes, relations, systems, transformations and implica-

education and research. It covers a mixture of well-known and tions. Examples of tests are "Names for stories," "Different let-

little-known procedures, but cannot do more than give some ter groups," or "Making objects." Scoring of the tests concen-

idea of the range of instruments that exist. The contents are trates on free production of a large number of ideas, not

organized in terms of creativity-related concepts (e.g., creative originality or effectiveness. The test manual reports internal

products, creative processes, creative person). At the end of the reliabilities ranging from .42 to .97, mostly however, between

article the dimensions of creativity that emerge from the tests .70 and .85. Test scores correlate only moderately with teacher

are presented in tabular form (see Table 1), and their psycho- ratings of creativity, and at a low level (-.06 to .35) with the

metric properties summarized (see Table 2). nowadays better known Torrance Tests discussed below. Also

based on the SI model, the Structure of the Intellect Learning

Abilities Test: Evaluation, Leadership, and Creative Think-

Creative Products ing (SOI: ELCT) (Meeker, 1985) measures eight cognitive

activities connected with creativity, all of them involving

divergent thinking: divergent symbolic relations, divergent

An early procedure for rating the creativity of products

symbolic units, divergent figural units, divergent semantic

was Taylor's (1975) Creative Product Inventory, which mea-

units, divergent semantic relations, divergent semantic trans-

sures Generation, Reformulation, Originality, Relevancy,

Hedonics, Complexity, and Condensation. More recently,

Besemer and O'Quin (1987) developed the Creative Product Manuscript submitted March, 2000.

Revision accepted September, 2000.

72/Roeper Review, Vol. 23, No. 2

formations, divergent figural relations, and divergent figural within the group being tested (uniqueness). Nowadays, some

transformations. Factor-analytic studies support the construct users also score the test for flexibility, originality (statistical

validity of this test and inter-rater reliabilities are often very uncommonness), and usefulness (practicality and relevance to

high (up to .99). reality). Fluency and flexibility require merely counting, but

originality and usefulness involve rating answers on a 7-point

T he best-known of the tests based on divergent think-

ing, however, are the Torrance Tests of Creative

Thinking (TTCT), initially published in 1966 and since

scale (not original - very original; not useful - very useful).

Kogan (1983) listed many studies supporting the validity and

revised (Torrance, 1999). The test materials include a verbal reliability of this test. More recently, Vosburg (1998) reported

section "Thinking Creatively with Words," and a nonverbal inter-rater reliabilities of .92 for originality ratings and .83 for

or figural section, "Thinking Creatively with Pictures," both usefulness. An overall alpha (internal consistency) reliability

of them having two forms, A and B. There are six verbal of .86 was reported by the same author.

activities (Asking, Guessing Causes, Guessing Conse- further, frequently cited test of the foundation period

quences, Product Improvement, Unusual Uses, Unusual dn the 1960s was the Remote Associates Test (RAT;

Questions and Just Suppose) and three figural activities (Pic- Mednick, 1962). This test is now out of print, but because of its

ture Construction, Picture Completion and Lines/Circles). seminal influence on creativity testing it will be discussed here.

The verbal activities yield scores on three dimensions It is based on the fact that some people are better than others at

(referred to by Torrance as "mental characteristics"): Fluen- finding remote associates to stimulus words: These people are

cy, Flexibility and Originality. The nonverbal activities yield rated more creative. Each of the 30 items, for which 40 minutes

scores for five mental characteristics: Fluency, Originality, are allowed, consists of several apparently unrelated words

Elaboration, Abstractness of Titles, and Resistance to Prema- (e.g., moon, cheese, and grass) and the task is to find a remote

ture Closure. In addition, the figural tests can be scored for fourth word that links these words (in the case of the example

Downloaded by [Western Kentucky University] at 03:55 03 May 2013

13 creative strengths (e.g., Storytelling Articulateness, Syn- just given blue would be appropriate). The score is the number

thesis of Incomplete Figures, and Fantasy). of correct solutions. Mednick reported internal consistency

The test manual reports a median inter-rater reliability coefficients of .91 and .92 respectively when the test was

derived from a number of studies of the verbal activities of the administered to samples of male and female undergraduates.

TTCT of as high as .97, and other research (see for instance The correlation with instructors' ratings on a university level

Sweetland & Keyser, 1991) indicates that the figure is com- design course was .70, and the scale distinguished significantly

monly greater than .90 for both parts. According to Treffinger between psychology students rated as creative researchers and

(1985) test-retest reliabilities of the various subdimensions those rated as low on creativity. Scores on the RAT also distin-

commonly lie between .60 and .70. Mumford, Marks, Connel- guished between students with liberal social attitudes and those

ly, Zaccaro and Johnson (1998) asked judges to use a 5-point with conservative attitudes, as well as between those with artis-

rating scale ranging from low to high to rate, among other tic and those with mechanical-agricultural vocational interests.

things, quality (in essence, effectiveness), originality, com- However, as Kasof (1997) summarized relevant findings, the

plexity, and realism of answers on the Guessing Consequences RAT has not shown more than moderate correlations with cre-

subtest, and after a practice run and a meeting to discuss the ative behavior in nontest situations.

basis of ratings the judges achieved inter-rater reliabilities of An important advance in creativity testing in recent years

.90 for quality, .86 for complexity, and .84 for originality. The derives from increasing recognition of the fact that actual cre-

figure for realism was somewhat lower at .65. ative production does not depend on divergent thinking alone,

but also requires convergent thinking (e.g., Rickards, 1994;

A recent study by Plucker (1999) used sophisticated sta-

tistical procedures to reanalyze 20-year longitudinal

data on predictive validity originally collected by Torrance .

Brophy, 1998). Rickards argued that the process of producing

effective novelty needs both kinds of thinking in order to be

He concluded that composite verbal (but not figural) creativity complete. Facaoaru (1985) called for a two track testing proce-

scores on the TTCT (obtained by averaging scores on three dure, which assesses the area of overlap between the two kinds

testings) accounted for about 50% of the variance of scores on of thinking (e.g., goal-directed divergent thinking). Sternberg's

the criterion of publicly recognized creative achievements and Triarchic Abilities Test (Sternberg, 1997) emphasizes that

participation in creative activities obtained several years later, intellectual ability can be better understood in terms of several

and predicted about three times as much of the criterion vari- facets, in this case Analytical Ability, Practical Ability and - of

ance as IQs. This corresponds to a predictive validity coeffi- particular interest for the present discussion - Synthetic Ability.

cient of about .7. The TTCT's scores differentiate well So far, the test includes material for two age levels: 8-10 years

between students who subsequently go on to achieve public and 15 years and up. The creativity test (Synthetic Ability)

acclaim as creative and those who do not. involves both multiple-choice items and an essay. The people

Another influential creativity test to appear during this being tested are also required to perform novel numerical oper-

period was that of Wallach and Kogan (1965), whose major ations. According to Sternberg (1997), this procedure is reli-

contribution was perhaps their emphasis on a gamelike atmos- able, displays construct validity - creativity scores correlate

phere and the absence of time limits in the testing procedure. only moderately with those on the other two dimensions-and

This test contains three verbal subtests (Instances, Alternate possesses predictive validity in that test scores correlate with

Uses and Similarities) and two subtests consisting of ambigu- grades in university courses that emphasize creativity.

ous figural stimuli (Pattern Meanings, Line Meanings). Proba- Urban and Jellen's (1996) Test of Creative Thinking

bly the most widely applied subtest is Alternate Uses, which, (Divergent Production) (TCT-DP) takes a different approach

as the name suggests, asks respondents to give as many unusu- from those of the procedures described above. It derives

al uses as they can for various common items (e.g., newspaper, scores from what the authors call image production. Respon-

knife, car tire, button, shoe, key). Originally, the test was dents' productions are rated according to dimensions derived

scored by counting the number of responses (fluency) and by from a Gestalt-psychology theory of creativity. These include

identifying responses that were unique to a specific person Boundary Breaking, New Elements, and Humor and Affectiv-

December, 2000, Roeper Review/73

ity. The test has two forms, A and B, on each of which dents are required to find the correct answer, and a scoring key

respondents are presented with a sheet of paper containing is provided that contains these answers. According to Doolittle

incomplete figures. Their task is to make a drawing or draw- the test, which is in some ways reminiscent of the RAT (see

ings containing the fragments, in any way they wish. Studies above), requires associative, inductive and divergent thinking.

in a number of different countries indicate that the inter-rater Since answers are specified in the scoring key, inter-rater relia-

reliability of the test is above .90, while test-retest reliability bility is not an issue. The author reported split-half reliabilities

is about .70-.75. The test manual reports correlations up to .82 of .63-.99 for Form A and .90 for Form B, and validity (corre-

with teacher ratings of creativity, and correlations with real- lations with scores on the RAT) of .70, the latter scarcely sur-

life criteria show that TCT-DP scores distinguish between prising in view of the similarity of contents.

people who follow acknowledged creative pursuits and those

who do not.

I<[n examining creative thinking Mumford and coworkers

(for a summary, see Mumford, Supinski, Baughman,

Costanza & Threlfall, 1997) focused on problem solving. They

The Creative Person

Biographical inventories

developed tests of Problem Construction, Information Encod-

The two best known instruments of this kind are Schaefer

ing, Category Selection, and Category Combination and Reor-

and Anastasi's (1968) biographical inventory and Taylor's

ganization. The category combination test, for instance,

(Taylor & Ellison, 1968) Alpha Biographical Inventory

involves problems consisting of sets of four exemplars of each

(ABI). They are now relatively old and do not focus exclusive-

of three categories. To take an example in the style of Mum-

ly on creativity: the ABI actually gives equal weight to con-

ford et al. (1997), a problem could consist of the following

ventional academic achievement. Schaefer and Anastasi's

three sets of exemplars: table, chair, lamp, bed; banana,

inventory will be reviewed here to give an idea of the nature of

Downloaded by [Western Kentucky University] at 03:55 03 May 2013

pineapple, orange, peach; telephone book, search warrant, mar-

such scales. It consists of 165 items, the ABI 300, some of

riage certificate, map. These are given without naming the cat-

them in multiple-choice format, some involving selecting from

egories defined by the exemplars. The respondents' task is to

alternatives, and some open- ended. The scale focuses on fac-

identify the categories defined by the exemplars; to combine

tual information, and measures five areas: family background

these categories to create a new, superordinate category; to

(e.g., educational level of parents, degree of public recognition

provide a label for the new category and write a brief, one-sen-

of parents or siblings), intellectual and cultural orientation

tence description of it; to list as many additional exemplars of

(e.g., interests and hobbies, level of availability of demanding

the supercategory as possible; to list additional features linking

literature, frequency of visits to museums or art galleries),

the exemplars combined in the new category. A respondent

motivation (possession and use of special equipment such as a

might identify the three subordinate categories in the example

microscope, willingness to skip meals to work on a project,

above as furniture, fruit and printed documents, and might then

taking summer jobs in a field of interest)-referred to by Schae-

combine these to form the supercategory of "forest products,"

fer and Anastasi as pervasive and continuing enthusiasm,

supporting this with the explanatory sentence, "All the furni-

breadth of interest (number of hobbies pursued, number of

ture could be made of wood, all the documents of paper (which

favorite school subjects), and drive towards novelty and diver-

is made from wood), and fruit and wood come from trees,

sity (level of interest in unusual art forms, extent of unconven-

which grow in a forest."

tional collections such as spider webs).

In Mumford et al's study, five judges rated the respon-

dents' products on a 5-point scale for quality and originality of

solutions. After a brief discussion to iron out discrepancies,

T wo scoring keys are available, one yielding a score for

Artistic Creativity, the other for Scientific Creativity.

In a study of students in the last three years of high school the

inter-rater reliabilities of .84 and .81 were achieved for quality

authors concluded that the scale discriminates significantly

and originality respectively. When Category Combination

between creative adolescents and members of matched control

scores were compared with a criterion consisting of originality

groups, the criterion of creativity being teachers' ratings of

of solutions to simulated management and advertising prob-

products produced by the students. They reported a validity of

lems correlations of .32 and .40 were achieved. Similar coeffi-

.64 for the artistic subscale and .35 for the scientific. The test

cients were obtained for Problem Construction, Information

correctly identified 96% of the students whose products were

Encoding and Category Selection with the same criteria. When

rated by teachers as artistically creative, although 34% of the

Problem Construction, Information Encoding, Category Selec-

noncreative were falsely selected (false positives). It selected

tion, and Category Combination scores were combined in a

46% of the scientifically creative (10% false positives).

regression approach, the multiple correlations with originality

of the solutions to the advertising task was .45, with originality More recenly, Michael and Colson (1979) developed the

of the management task .61. Life Experience Inventory (LEI). The 100-item inventory

concentrates on factual information (e.g., number of changes

A problem-solving test that adopts a novel approach is

the Creative Reasoning Test (CRT) (Doolittle, 1990).

This test has two levels, Level A for Grades 3-6 and Level B

of address in childhood, composition of family, education,

hobbies and recreation). As the authors pointed out, this

approach enhances reliability. In an initial study of 100 electri-

for secondary and college level. There are two forms of each cal engineers who had also been classified as creative or non-

level (Form 1 and Form 2), each with 20 items. A novel aspect creative on the basis of whether or not they held patents, 49

of this test is that the problems to be solved are presented in items differentiated between creative and noncreative partici-

the form of riddles. At Level A, for instance, these take the pants. An intuitive grouping of these items by the authors indi-

form of four-line rhymes, in which some animal or object cated that they cover four areas: self-striving or self-improve-

gives clues to its identity, and respondents must work out what ment (e.g., enjoying competition, displaying curiosity, being

the animal or object is. An example in the style of this test committed to an area of interest), parental striving (parental

would be: I grow in the park, / where I stand tall and green./ emphasis on getting ahead, perceived need to do well in order

For birds I am home./ When the wind blows I lean. Respon- to satisfy parents), social participation and social experience

74/Roeper Review, Vol. 23, No. 2

(membership of organizations, helping other students with 33-item scale for grades 5-6. GIFFI has two levels (I for

their schoolwork), and independence training (being allowed junior high school and II for senior high school), which each

as children to choose their own friends, being allowed to set contain 60 items. As the names imply, the tests can be admin-

their own standards in judging their own accomplishments). In istered in a group setting. Children rate themselves by answer-

a cross-validation study based on real-life achievements of 98 ing Yes or No to statements such as, "I like to make up my

engineers, a validity coefficient of .62 was obtained (criterion own songs," or "Easy puzzles are the most fun." The tests

= possession or not of patents). No less than 83% of the engi- yield scores for traits like curiosity, originality, independence,

neers above the cutoff point on the inventory were indeed cre- flexibility, or risktaking. Davis and Rimm reported internal

ative according to the criterion (i.e., correctly identified), consistencies of .80-.88 and a test-retest reliability of .56 for

although 29% of those not identified were, according to the GIFT and .88 and .94 for GIFFI I and GIFFI II respectively.

criterion, actually creative (false negatives). In various studies with GIFT validity was measured by corre-

lating test scores with teacher ratings, judged creativity of

R unco (1987) developed the Creative Activities Check-

list, suitable for use with children in Grades 5 to 8.

The test simply asks participants to indicate how frequently

drawings and judged creativity of stories. The resulting coeffi-

cients ranged from .07-.54, but were in the main in the area

they have participated in recent times in real-life activities in .30-.40. In the case of GIFFI I and GIFFI II, correlations

six areas: literature, music, drama, arts, crafts, and science. with teachers' ratings ranged from .21 to .68.

Scoring can be carried out by simply adding the number of Kumar, Kemmler and Holman's (1997) Creativity Styles

instances of participation in, for instance, the last year (e.g., Questionnaire (CSQ) measures seven dimensions: Belief in

writing a story or poem, playing at a school, church or club Unconscious Processes; Use of Techniques; Use of Other Peo-

concert, acting in a school play, participating in a science fair, ple; Final Product Orientation; Environmental Control; Super-

and so on). In some studies respondents merely list their three stition; Use of Senses. Participants rate themselves on 76 items

Downloaded by [Western Kentucky University] at 03:55 03 May 2013

most creative achievements to date. These can then be rated for (e.g., "Creative ideas occur to me without even thinking about

degree of creativity. Runco (1987) reported inter-rater reliabili- them," "When I get a new idea, I get completely absorbed by

ties in excess of .90 for such ratings. Very recently, Russ, it," or "I typically create new ideas by combining existing

Robins & Christiano (1999) reported alpha coefficients of ideas"), using a 5-point scale ranging from "Strongly agree" to

about .90 for reliability of the total scale and from about .50- "Strongly disagree." The authors reported alpha coefficients

.85 for the various areas. for the seven subscales ranging from .45-.83. Another recent

self-rating scale is the Abedi-Schumacher Creativity Test

Special personal properties (O'Neil, Abedi & Spielberger, 1994), a multiple choice test on

A second approach to the study of the creative person which students rate themselves on 60 questions regarded as

involves identifying personal characteristics whose presence is indicators for fluency, flexibility, originality, or elaboration

thought to increase the likelihood of creativity or even to be (e.g., "How do you approach a complex task?"). Auzmendi,

essential for its appearance. The Creativity Checklist (CCL) Villa and Abedi (1996) reported internal reliabilities of .61 to

(Johnson, 1979) can be used for rating people at all age levels, .75 (average = .66) for the four subscales when a Spanish ver-

including adults in work settings. On a 5-point scale ranging sion of the test was administered to over 2,200 children. Scores

from never to consistently, observers rate the behavior of the on the subscales correlated only between .02 and .32 with

people being assessed on eight dimensions: In addition to the teachers' ratings of creativity (average correlation = .24) and

cognitive dimensions Fluency, Flexibility, and Constructional scores on the TTCT (average correlation =.11). The reliabili-

Skills, personal properties such as Ingenuity, Resourcefulness, ties also fell short of customary levels. Despite this, Auzmendi,

Independence, Positive Self-Referencing, and Preference for Villa and Abedi concluded that further refinement of the scale

Complexity are assessed. Inter-rater reliabilities ranged from would easily deal with this shortcoming. These authors also

.70 to .80, and the test correlated between .51 (RAT) and .56 reported data on a further self-rating scale, the Villa and Auz-

(TTCT) with other tests. mendi Creativity Test, which consists of a list of 20 adjectives

such as imaginative, or flexible, on which students rate them-

The Creative Behavior Inventory (Kirschenbaum, 1989) selves using a 5-point scale ranging from very to not at all.

also involves ratings by observers. It has two forms, CBI1 for This test also yields scores for fluency, flexibility, originality,

Grades 1-6 and CBI 2 for Grades 7-12. The test contains 10 and elaboration. Internal consistencies for the subscales ranged

items, with ratings ranging from 1-10, according to the fre- from .14 to .69 (average = .41). Subscale scores correlated

quency with which the child behaves in the way indicated: e.g., from between .20 and .55 with subscales of the Abedi-Schu-

This child notices and remembers details. The ratings yield macher test.

scores on five dimensions: Contact, Consciousness, Interest,

Fantasy, and Total Score. The first four are thought to be lolangelo, Kerr, Huesman, Hallowell and Gaeth's

aspects of a phase of preparation in the process of creative '(1992) developed the Iowa Inventiveness Inventory,

thinking. The author reported an alpha coefficient of .93 for the initially by studying inventors who held industrial or agricul-

test, and showed that it distinguished well between children tural patents. The final instrument consists of 61 statements

who produced creative products in the course of an enrichment (e.g., Whenever I look at a machine, I look at a machine, I can

program and those who did not. see how to change it.) with which respondents indicate level of

agreement on a 5-point scale. The inventory distinguished sig-

S ome scales in this area involve self-ratings. An exam-

ple is the Group Inventory for Finding Creative Tal-

ent (GIFT) (Rimm & Davis, 1980) and its upward extension

nificantly between acknowledged creative individuals and

other people, for instance sorting into the expected older

the Group Inventory for Finding Interests (GIFFII and acknowledged inventors, young inventors rated as inventive by

GIFFIII) (Davis & Rimm, 1982). The authors describe these teachers, and noninventive academically-talented adolescents.

scales as measuring attitudes and interests associated with cre- The test-retest reliability of the inventiveness score reported by

ativity. There are three levels of GIFT: a 32-item scale for Colangelo et al was .66 and internal consistency was .70.

kindergarten to grade 2, a 34-item scale for grades 3-4, and a

December, 2000, Roeper Review/75

Motivation and attitudes total score, and test-retest reliability over seven months of .82

Directly related to the role of motivation in creativity is for the total score. Puccio, Treffinger and Talbot (1995) report-

Williams's (1972) How Do You Really Feel About Yourself? ed alpha reliabilities for the total score of .86-.88, and from

test, which measures curiosity, imagination, risk-taking and .61-.83 for the subscales. The same authors reported correla-

preference for complexity. This test has been used with school- tions ranging from about .25 to .47 for the subscale Originality

children in grades 6 to 12. More recent is Williams's (1980) with the rated originality of products.

Creativity Assessment Packet. This scale is designed for use

with children in grades 3-12. It includes 12 partially complete

figures that are completed by the child and scored for fluency,

B; 1 asadur and Hausdorf (1996) emphasized a somewhat

' different aspect of the personal correlates of creativi-

ty: attitudes favorable to creativity (e.g., placing a high value

flexibility, originality and elaboration. These are flanked by a on new ideas; believing that creative thinking is not bizarre).

self-rating scale involving 50 multiple-choice items that are The 24-item Basadur Preference Scale consists of statements

scored for divergent feelings (curiosity, risk-taking, desire for with which respondents express their degree of agreement/dis-

complexity, and imagination). There is also a rating scale for agreement on a 5-point scale ranging from strong agreement to

use by parents or teachers on which they rate the frequency of strong disagreement. Items include "Creative people generally

behaviors indicating the presence of the traits just mentioned. seem to have scrambled minds," "New ideas seldom work

The test manual reports test-retest reliabilities over 10 months out," or "Ideas are only important if they impact on major pro-

'in the .60s', and unspecified validity coefficients of .71-.76. jects." Factor analysis yielded three dimensions when the scale

Test scores were also reported to correlate from .59-.74 with was administered to university students and young adults

adult ratings of the children's creativity. Presumably, inter- working in business settings: Valuing New Ideas, Creative

rater reliabilities and internal consistencies were higher than Individual Stereotypes, and Too Busy for New Ideas. Test-

.60+, as the validity coeficients just mentioned would other- retest reliabilities of the three dimensions ranged from .58-.63,

Downloaded by [Western Kentucky University] at 03:55 03 May 2013

wise be impossible while alpha coefficients ranged from .58-.76. Basadur and

Hausdorf reported validity coefficients involving correlations

T he Creatrix Inventory (C & RT) (Byrd, 1986) is of

considerable interest, because it integrates both cogni-

tive (thinking) and noncognitive (motivation) dimensions of

with other creativity tests of about .25.

creativity. It is based on the concept of idea production, the

ability to produce unconventional ideas, creativity being Procedures Based on the

regarded as the result of an interaction between creative think- Adjective Check List

ing and the motivational dimension of risk-taking. The test

consists of two blocks of 28 self-rating or attitude statements, The Adjective Check List (ACL) (Gough & Heilbrun,

one block measuring creative thinking, the other risk-taking. 1983) can be used for both self-ratings and also for ratings by

These are answered using a 9-point scale ranging from com- observers. In an early application to measuring creativity

plete disagreement to complete agreement (e.g., "I often see Smith and Schaefer (1969) developed a 27-item subset of

the humorous side when others do not," "Daydreaming is a adjectives that discriminated significantly between groups of

useful activity"). Scores on the items of each dimension are high school students judged by their teachers to be more or

summed and the total score for the dimension rated as high, less creative, as well as between scientists and engineers

medium, or low. Each person's scores are then plotted on a judged on the basis of a biographical inventory to be creative

two-dimensional matrix (creativity versus risk-taking) and the and others judged to be less creative. This scale also possessed

person assigned to one of eight styles: Reproducer, Modifier, a certain degree of construct validity, the scores of business

Challenger, Practicalizer, Innovator, Synthesizer, Dreamer, undergraduates correlating .63 with the originality subscale of

and Planner. The innovator is high on both creative thinking Kirton's Adaptor-Innovator Scale (see above), .41 with self-

and risktaking, the reproducer low on both, the challenger high ratings of creativity, and .48 with colleagues' ratings. Domino

on risktaking but not creativity, the dreamer high on creativity developed a 59-item subscale of the ACL, the Domino Cre-

but not risktaking, and so on. Byrd reported a one-week test- ativity Scale, that also discriminated between several groups of

retest reliability of .72 for this scale. He argued that the scale more and less creative college students, when used by instruc-

possesses face validity, but provided no data on other forms. tors to rate the students (Domino, 1994). The criterion of cre-

Kirton's (1989) Adaptation-Innovation Inventory (KAI) ativity involved either instructors' ratings or choice of a cre-

does not mention creativity in its title, but is frequently cited in ative course (e.g., dance, music, cinematography).The scale

creativity research. This test distinguishes between people who also discriminated significantly between inventors and nonin-

seek to solve problems by making use of what they already ventors. Other assessments of validity yielded values of up to

know and can do (adaptors), and people who try to reorganize .65 (correlations with other creativity scales), .63 (self-ratings

and restructure the problem (innovators). Kirton's view is that of creativity), .55 (colleagues' ratings), or .34 (instructors' rat-

both adapting and innovating are involved in creative problem- ings). The Schaefer and Domino scales correlate about .90

solving, but the innovative style (which is accompanied by with each other, scarcely surprising when it is borne in mind

greater motivation to be creative, higher levels of risktaking, that they have 19 common items. Domino reported internal

and greater self-confidence) leads to higher productivity. The reliability of .88-.91 for his scale.

scale consists of 32 items (e.g., Will always think of something I ough himself developed the 30-item Creative Person-

when stuck, Is methodical and systematic, Often risks doing

things differently) on which respondents rate themselves, indi-

G: (ality Scale (Cps) (Gough, 1992; Gough & Heilbrun,

1983), largely because both the Schaefer and Domino scales

cating how difficult it would be for them to be like this on a showed little or no correlation with the rated creativity of

5-point scale (very easy - very hard). The procedure yields an mature scientists, despite their usefulness with schoolchildren

overall score and scores on three subscales: Originality, and college students. This subscale, which has become a rou-

Conformity, and Efficiency. Kirton himself reported KR20 tine element of the scoring of the ACL, involves 18 adjectives

reliabilities of from .76-.82 for the subscales and .88 for the that receive a positive weight (e.g., clever wide interests, origi-

76/Roeper Review, Vol. 23, No. 2

nal) and 12 that receive a negative weight (e.g., sincere.conven- eral picture. The table does not reflect nonnumerical findings

tional, commonplace). Its scores differentiate between creative unsupported by relevant coefficients, such as statements in

and less creative adults in many, but not all, studies. Reported some studies that creativity tests were good predictors of

reliability coefficients for the Cps are often about .80, although adult creativity.

Gough and Heilbrun themselves reported an internal consisten-

cy coefficient of .63, and test-retest reliabilities of about .70,

depending on gender. It correlates moderately with scores on A Stocktaking

Guilford tests of divergent thinking (about .25) and with mea-

sures of openness, as well as with self-assessments (.41) and Inter-rater reliabilities in excess of .90 are frequently

peer assessments (.48) of creativity, while correlations with cre- reported for creativity tests, while internal consistencies com-

ativity at work, in university studies (as rated by faculty mem- monly reach .80, and test-retest reliabilities range from .60-.80.

bers), and in biographical inventories are about .40. Thus, the dimensions they measure can be assessed with high

agreement among raters, people taking the tests behave in a

consistent manner within a single testing, and scores are rea-

Overview sonably stable over time. A comparison with data for the high-

ly respected Wechsler intelligence scales shows that the fig-

The creativity tests reviewed here define creativity in a ures for creativity tests are better than some critics have

multifaceted way (products, processes and personal factors). suggested. For the subtests of the WISC-R Sattler (1992) listed

An overview of these facets is given in Table 1. split-half reliabilities (these are usually higher than test-retest

Table 2 summarizes the data on reliability and validity coefficients) ranging from .70-.86 (Mdn = .77).

presented in this article. For ease of reference, the coeffi- In the case of validity, the fact that the highest coefficients

Downloaded by [Western Kentucky University] at 03:55 03 May 2013

cients cited in the table have been rounded up or down by were for correlations of divergent thinking tests with each

placing only 0 or 5 in the second decimal place, as well as other (up to .70) is scarcely surprising, since these tests focus

being bunched by omitting outlier values that distort the gen- on the cognitive aspect of creativity and thus embody the most

Test defined elements of creativity

PRODUCT PROCESS MOTIVATION PERSONALITY/ABILITIES

• Originality • "Uncensored" perception and • Goal-directedness • Active imagination

• Relevance encoding of information • Fascination for a task or area • Flexibility

• Usefulness • Fluency of ideas (large number • Resistance to premature • Curiosity

• Complexity of ideas) closure • Independence

• Understandability • Problem recognition and • Risk-taking • Acceptance of own

p n n loll

UUI Q t nUvLIUI

if^tinn1

• Pleasingness • Preference for asymmetry differentness

• Unusual combinations of ideas

• Elegance/Well-craftedness • Preference for complexity • Tolerance for ambiguity

(remote associates, category

• Germinality combination, boundary • Willingness to ask many • Trust in own senses

breaking) (unusual) questions • Openness to sub-conscious

• Construction of broad • Willingness to display results material

categories (accommodating) • Willingness to consult other • Ability to work on several ideas

• Recognizing solutions people (but not simply to carry simultaneously

(category selection) out orders) • Ability to restructure problems

• Transformation and • Desire to go beyond the • Ability to abstract from the

restructuring of ideas conventional concrete

• Seeing implications

• Elaborating and expanding

ideas

• Self-directed evaluation of

ideas

Table 1

Psychometric properties of creativity tests

Reliability Validity

Aspect of Creativity Internal Test-Retest Inter-rater Ratings Other Tests Real Life

Creative Products .70-.90+ .70-.90+

Creative Thinking .70-.90+ .60-.75 .65-.90+ .25-70 up to .70 .30-.70

The Creative Person

- Biographical inventories .50-.90 .90 .60

- Special personal properties .45-.90+ .55-.80+ .70-.90 .20-.70 .20-.60 .30-.40

- Motivation and attitudes .60-.80+ .60-.80 .75+ .60-.70 .20-.55 .25-.50

Adjective Check Lists .65-.90 .70 — .30-.50 .25-.65 .40-.50

Table 2

December, 2000, Roeper Review/77

unitary definition of it. Measures of creative person correlate ed in the handbook (Urban & Jellen, 1996) or by combining

lower at about .50 with other similar tests. These validity coef- subtest scores to form the three more-complex dimensions

ficients can be compared with construct validity coefficients Productivity, Novelty and Unconventionality that have been

(correlations with other intelligence tests) for WISC-R Verbal demonstrated factor-analytically (e.g., Cropley & Cropley,

and Performance IQs ranging from .26-.75 (Mdn = .61) report- 2000). Focus on a multidimensional concept of creativity, on

ed by Sattler. The IQs are composites obtained by summing assessment of potential and on the use of tests as a basis for

six subtests, so that the validity coefficients are enhanced by differentiated counseling suggests that creativity tests are

combining information from several sources. Lower correla- worth using.

tions among tests of personal properties than among cognitive

tests would be expected if individual tests measure different REFERENCES

aspects of the creative person. Table 1 suggests that this is the Auzmendi, E., Villa, A., & Abedi, J. (1996). Reliability and validity of a newly construct-

ed multiple-choice creativity instrument. Creativity Research Journal, 9, 89-96.

case. Because of the multifaceted nature of creativity as mea- Baldwin, A. Y. (1985). Programs for the gifted and talented: Issues concerning minority

sured by tests, Davis and Rimm (1998) recommended that populations. In F. D. Horowitz & M. O'Brien (Eds.), The gifted and talented:

assessments should be based on several different tests. Developmental perspectives (pp.223-250). Washington, D.C.: American Psychologi-

cal Association,

T he tests' ability to predict achievements in real life,

sometimes years later, also involved coefficients

around .50. By contrast, IQs frequently correlate about .70

Basadur, M., & Hausdorf, P. A. (1996). Measuring divergent thinking attitudes related to

creative problem solving and innovation management. Creativity Research Journal,

9, 21-32.

Besemer, S. P. (1998). Creative Product Analysis Matrix: Testing the model structure and

a comparison among products-three novel chairs. Creativity Research Journal, 11,

with school grades, although much lower with gifted achieve- 333-346.

ments in adult life (e.g., Gibson & Light, 1967). One possible Besemer, S. P., & O'Quin, K. (1987). Creative product analysis: Testing a model by

developing a judging instrument. In S. G. Isaksen (Ed.), Frontiers of creativity

explanation for the lower predictive validity of creativity tests research: Beyond the basics (pp. 367-389). Buffalo, NY: Bearly.

is that their tasks do not resemble real-life creative behavior Besemer, S. P., & O'Quin, K. (1999). Confirming the three-factor Creative Product

Downloaded by [Western Kentucky University] at 03:55 03 May 2013

(questionable face validity), whereas the contents of intelli- Analysis Model in an American sample. Creativity Research Journal, 12, 287-296.

Brophy, D. R. (1998). Understanding, measuring and enhancing individual creative prob-

gence tests are rather like school tasks. It also seems likely that lem-solving efforts. Creativity Research Journal, 11, 123-150.

real-life creative achievement requires more than creativity, Byrd, R. E. (1986). Creativity and risk-taking. San Diego, CA: Pfeiffer International Pub-

lishers.

with other psychological factors also playing a major role. Carroll, J. B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Convergent thinking has already been mentioned. Further fac- Colangelo, N., Kerr, B., Huesman, R., Hallowell, N., & Gaeth, J. (1992). The Iowa Inven-

tiveness Inventory: Toward a measure of mechanical inventiveness. Creativity

tors were identified in a recent 30 year longitudinal study on Research Journal, 5, 157-164.

college women by Helson (1999): Youthful openness and Conoley, J. C., & Kramer, J. J. (Eds.). (1989). The 11th Mental Measurements Yearbook.

Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

unconventionality (typical characteristics emphasized in tests Cooper, E. (1991). A critique of six measures for assessing creativity. Journal of Creative

of the creative person) are strongly predictive of adult creative Behavior, 25, 194-204.

Cropley, D. H., & Cropley, A. J. (2000). Fostering creativity in engineering undergradu-

achievement when they are associated with depth, commitment ates. High Ability Studies, 12.

and self-discipline, but when accompanied by unresolved iden- Csikszentmihalyi; M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and

tity problems, lack of persistence, self-defeating behavior, or invention. New York: Harper Collins.

Davis, G. A., & Rimm, S. B. (1982). Group Inventory for Finding Interests (GIFFI) I and

overt psychopathology they are not. Consequently, a number II: Instruments for identifying creative potential in junior and senior high school.

of authors (e.g., Kitto, Lok & Rudowicz, 1994; Helson,1999) Journal of Creative Behavior, 16, 50-57.

Davis, G. A., & Rimm, S. B. (1998). Education of the gifted and talented. Needham

suggested that creativity tests are best thought of as tests of Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

creative potential, not of creativity. Domino, G. (1994). Assessment of creativity using the ACL: A comparison of four scales.

Creativity Research Journal, 7, 21-23.

Some writers have suggested that there is no need for a Doolittle, J. H. (1990). Creative Reasoning Test. Pacific Grove, CA: Midwest Publica-

tions/Critical Thinking Press.

separate concept creativity at all. Carroll (1993) argued that Facaoaru, C. (1985). Kreativität in Wissenschaft und Technik [Creativity in science and

cognitive tests do not measure a separate ability but Broad technology]. Bern: Huber.

Retrieval (Fluency). Wallach (1976, p. 57) concluded that tests Gibson, J., & Light, P. (1967). Intelligence among university scientists. Nature, 213, 441-

443.

tell us little about talent, Milgram (1990) asked whether cre- Gough, H. G. (1992). Assessment of creative potential in psychology and the develop-

ativity is a concept whose time has come and gone, and Czik- ment of a creative temperament scale for the CPI. In J. C. Rosen & P. McReynolds

(Eds.), Advances in psychological assessment (Vol 8, pp. 225-257). New York:

szentmihalyi (1996) argued that creativity is simply a diffuse Plenum.

category of positive judgment in the mind of critics. Nonethe- Gough, H. G., & Heilbrun, A. B. (1983). The Adjective Check List Manual (2nd. ed,).

Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

less, Hocevar (1981) concluded that children's degree of par- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5, 444-454.

ticipation in creative activities out of school is a defensible Guilford, I. P. (1976). Creativity Tests for Children. Orange, CA: Sheridan Psychological

Services.

way of assessing their creativity, and Baldwin (1985) conclud- Helson, R. (1999). A longitudinal study of creative personality in women. Creativity

ed that dedicated pursuit of an interest is the best indicator in Research Journal, 12, 89-102.

minority and disadvantaged children. Kumar, Kemmler and Hennessey, B. A. (1994). The consensual assessment technique: An examination of the

relationships between ratings of product and process creativity. Creativity Research

Holman (1997) emphasized that self-rating scales have a cer- Journal, 7, 193-208.

tain phenomenological authenticity, since respondents describe Hocevar, D. (1981). Measurement of creativity: Review and critique. Journal of Person-

ality Assessment, 45, 450-464.

themselves. Hocevar, D., & Bachelor, P. (1989). A taxonomy and critique of measurements used in

the study of creativity. In J. A. Glover, R. R. Ronning & C. R. Reynolds (Eds.),

A mong tests of creative thinking the TTCT-DP has

much to recommend it. It is based on a more general

theory of creativity than the relatively ad hoc test-derived

Handbook of creativity (pp. 53-76). New York: Plenum.

Johnson, D. L. (1979). The Creativity Checklist. Wood Dale, IL: Stoelting.

Kaltsounis, B., & Honeywell, L. (1980). Instruments useful in studying creative behavior

and creative talent. Journal of Creative Behavior, 14, NNNNN56-67.

models centering on divergent thinking (Torrance) or diver- Kasof, J. (1997). Creativity and breadth of attention. Creativity Research Journal, 10,

303-315.

gent production (Guilford), and encompasses both thinking Kirschenbaum, R. J. (1989). Understanding the creative activity of students. Mansfield,

and personality. My own experience confirms that it is also CT: Creative Learning Press.

suitable for administration to people over a very wide age Kirton, M. J. (Ed.). (1989). Adaptors and innovators: Styles of creativity and problem-

solving (pp. 56-78). London: Routledge.

range, is readily accepted by respondents, is easy to administer Kitto, J., Lok, D., & Rudowicz, E. (1994). Measuring creative thinking: An activity-based

and score, and can be used for counseling purposes (see for approach. Creativity Research Journal, 7, 59-69.

Kogan, N. (1983). Stylistic variation in childhood and adolescence: Creativity, metaphor,

instance Cropley & Cropley, 2000). The scores can be used and cognitive styles. In P. Mussen (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology, Vol. 3 (pp.

either at the differentiated level of the 13 dimensions suggest- 631-706). New York: Wiley.

78/Roeper Review, Vol. 23, No. 2

Kramer, J. J., & Conoley, J. C. (Eds.). (1989). The 11th Mental Measurements Yearbook Russ, S. W., Robins, A. L., & Christiano, B. A. (1999). Pretend play: Longitudinal predic-

Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. tion of creativity and affect in fantasy in children. Creativity Research Journal, 12,

Kumar, V. K., Kemmler, D., & Holman, E. R. (1997). The Creativity Styles Question- 129-139.

naire-Revised. Creativity Research Journal, 10, 51-58. Sattler, J. M. (1992). Assessment of children. San Diego, CA: Author.

Mednick, S. A. (1962). The associative basis of the creative process. Psychological Schaefer, C. E., & Anastasi, A. (1968). A biographical inventory for identifying creativity

Review, 69, 220-232. in adolescent boys. Journal of Applied Psychology, 52, 42-48.

Meeker, M. (1985). Structure of Intellect Learning Abilities Test. Los Angeles: Western Schaefer, C. I. (1971). The Creative Attitude Survey. Jacksonville, IL: Psychologists and

Psychological Services. Educators Inc.

Michael, W. B., & Colson, K. R. (1979). The development and validation of a life experi- Smith, J. M., & Schaefer, C. E. (1969). Development of a creativity scale for the Adjec-

ence inventory for the identification of creative electrical engineers. Educational and tive Check List. Psychological Reports, 25, 87-92.

Psychological Measurement, 39, 463-470. Sternberg, R. J. (1997). Intelligence and lifelong learning. What's new and how can we

Milgram, R. M. (1990). Creativity: An idea whose time has come and gone? In M. A. use it? American Psychologist, 52, 1134-1139.

Runco & R. S. Albert (Eds.), Theories of creativity (pp. 215-233). Newbury Park, Sweetland, R. C., & Keyser, D. J. (1991). A comprehensive reference for assessment in

CA: Sage. psychology, education and business. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Milgram. R. M., & Hong, E. (1999). Creative out-of-school activities in intellectually gift- Taylor, A. (1975). An emerging view of creative actions. In I. A. Tylor, & J. W. Getzels

ed adolescents as predictors of their life accomplishments in young adults: A longitu- (Eds.), Perspectives in creativity (pp. 297-325). Chicago: Aldine.

dinal study. Creativity Research Journal, 12, 77-88. Taylor, C. W., & and Ellison, R. L. (1968). The Alpha Biographial Inventory. Greens-

Mumford, M. D., Marks, M. A., Connelly, M S., Zaccaro, S. J., & Johnson, J. F. (1998). boro, NC: Prediction Press.

Domain-based scoring of divergent-thinking tests: Validation evidence in an occupa- Torrance, E.P. (1999). Torrance Test of Creative Thinking: Norms and technical manual.

tional sample. Creativity Research Journal, 11, 151-163. Beaconville, IL: Scholastic Testing Services.

Mumford, M. D., Supinski, E. P., Baughman, W. A., Costanza, D. P., & Threlfall, K. V. Torrance, E. P., & Goff, K. (1989). A quiet revolution. Journal of Creative Behavior, 23,

(1997). Process-based measures of creative problem-solving skills: V. Overall predic- 136-45.

tion. Creativity Research Journal, 10, 73-85. Treffinger, D. J. (1985). Review of Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. Ninth Mental

O'Neil, H. F., Abedi, J., & Spielberger, C. D. (1994). The measurement and teaching of Measurements Yearbook (pp. 1632-1634). Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska

creativity. In H. F. O'Neil & M. Drillings (Eds.), Motivation: Theory and research Press.

(pp. 245-263). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Urban, K. K., & Jellen, H. G. (1996). Test for Creative Thinking - Drawing Production

Plucker, J. A. (1999). Is the proof in the pudding? Reanalysis of Torrance's (1958 to pre- (TCT-DP). Lisse, Netherlands: Swets and Zeitlinger.

sent) longitudinal data. Creativity Research Journal, 12, 103-114. Vosburg, S. K. (1998). Mood and quantity and quality of ideas. Creativity Research Jour-

Puccio, G. J., Treffinger, D. J., & Talbot, R. J. (1995). Exploratory examination of rela- nal, 11, 315-324.

tionships between creativity styles and creative products. Creativity Research Jour- Wallach, M. A. (1976, January—February). Tests tell us little about talent. American Sci-

nal, 8, 157-172. entist, 57-63.

Downloaded by [Western Kentucky University] at 03:55 03 May 2013

Rickards, T. J. (1994). Creativity from a business school perspective: Past, present and Wallach, M. A., & Kogan, N. (1965). Modes of thinking in young children. New York:

future. In S. G. Isaksen, M. C. Murdock, R. L. Firestien & D. J. Treffinger (Eds.), Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Nurturing and developing creativity: The emergence of a discipline (pp. 155-176). Williams, F. E. (1972). A total creativity program for individualizing and humanizing the

Norwood, NJ: Ablex. learning process. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology Publications.

Rimm, S., & Davis, G. A. (1980). Five years of international research with GIFT: An Williams, F. E. (1980). The Creativity Assessment Packet. Chesterfield, MO: Psycholo-

instrument for the identification of creativity. Journal of Creative Behavior, 14, 35-46. gists and Educators Inc.

Runco, M. A. (1987). Interrater agreement on a socially valid measure of students'creativ-

ity. Psychological Reports, 61, 1009-1010.

Conferences

Arkansas for Gifted and Talented North Carolina Association of Gifted World Council for Gifted and Talented

(AGATE) NCAGT/PAGE July 31-August 4, 2001

February 21-23, 2001 March 15-17, 2001 Barcelona, Spain

Hot Springs, Arkansas Contact: Wesley Guthrie, 910-326-8463 Contact: WorldGT@eaarthlink.net

Contact: Bonnie Haynie: 501 847-5642 Dr. Juan Alonso: 34-983-3413-82

The Association for the Education of

Gifted Underachieving Students

Nebraska Association for the Gifted (AEGUS) Annemarie Roeper Symposium 2001

Annual Conference March 30-31, 2001 September 21-23, 2001

February 22-23., 2001 Becker College Chicago, Illinois

Lincoln, Nebraska Worcester, Massachusetts Contact: Betty Meckstroth

Contact: Kay Grimminger Contact: Gail Herman, 301-387-9597 BetMeck@aol.com

kgrimmin @ esu 10.org gnherman @ mail2.gcnet.net

Kansas Association for Gifted Education

Kentucky Association for Gifted Pennsylvania Association For Gifted October 4-6,2001

Education - 21st Conference Education PAGE Topeka, Kansas

February 22-23, 2001 April 27-28, 2001 Contact: Bev Crowe

Lexington, Kentucky Marriott City Center bcrowe @ usd266.com

Contact: 270-745-4301, kagc@wku.edu Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Contact: Dee Weaver, 412-831-5873

mweaver@nb.net Gifted Education Association of Missouri

California Association for the Gifted October 14-16, 2001

March 1-3, 2001 Lake of the Ozarks, Missouri

Palm Springs, California Hollingworth Center Conference Contact: Donna Pfautsch 816-380-2412

Contact: CAG 310 215 1898 April 27-29, 2001 pfautsch@sky.net

Newton, Massachusetts

Contact: Kathy Kearney

Georgia Association for Gifted Children kkearney @ midcoast.com NAGC

March 8-10, 2001 November 7-11,2001

University of Georgia, Athens Cincinnati, Ohio

Contact: Dany Ray: danymray@cs.com Contact: www.nagc.org

December, 2000, Roeper Review/79

You might also like

- SHRM CompetenciesDocument87 pagesSHRM CompetenciesDillip100% (6)

- A Portfolio of Reflections: Reflection Sheets for Curriculum AreasFrom EverandA Portfolio of Reflections: Reflection Sheets for Curriculum AreasNo ratings yet

- Quantitative Research DesignsDocument16 pagesQuantitative Research Designsapi-339611548100% (15)

- D T Stage 5 1Document37 pagesD T Stage 5 1api-354436144No ratings yet

- Bok:978 3 319 18221 6 PDFDocument222 pagesBok:978 3 319 18221 6 PDFNarendraNo ratings yet

- Art AppreciationDocument10 pagesArt AppreciationRaindel Carl OlofernesNo ratings yet

- Creativity in Language TeachingDocument21 pagesCreativity in Language TeachingNaserElrmahNo ratings yet

- What Is ReliabilityDocument3 pagesWhat Is ReliabilitysairamNo ratings yet

- Wink Course Introduction EbookDocument68 pagesWink Course Introduction EbookInglês The Right WayNo ratings yet

- Using Biggs' Model of Constructive Alignment in Curriculum Design:Continued - UCD - CTAGDocument3 pagesUsing Biggs' Model of Constructive Alignment in Curriculum Design:Continued - UCD - CTAG8lu3dz100% (1)

- EFQM Excellence ModelDocument118 pagesEFQM Excellence Modelstudent dzNo ratings yet

- Ecological LiteracyDocument23 pagesEcological LiteracyGeorgia Alessandra Pareñas CañaveralNo ratings yet

- Nature of Inquiry and ResearchDocument16 pagesNature of Inquiry and ResearchAzeLuceroNo ratings yet

- Universal Methods of Design PDFDocument3 pagesUniversal Methods of Design PDFKeliElizabethBaldazoNo ratings yet

- A.I. in 2020 A Year Writing About Artificial Intelligence by Ribeiro, Jair (Ribeiro, Jair)Document311 pagesA.I. in 2020 A Year Writing About Artificial Intelligence by Ribeiro, Jair (Ribeiro, Jair)solid34No ratings yet

- Defining and Measuring Creativity: Are Creativity: Tests Worth Using?Document9 pagesDefining and Measuring Creativity: Are Creativity: Tests Worth Using?Toi La AiNo ratings yet

- Mapa ConceptualDocument2 pagesMapa ConceptualRossana Lucía Benites ZapataNo ratings yet

- Creativity 3Document20 pagesCreativity 3Ranganadh PanchakarlaNo ratings yet

- Cvsu Vision Cvsu Mission: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesCvsu Vision Cvsu Mission: Republic of The PhilippinesRUTHY ANN BALBIN BEEd 2-1No ratings yet

- Freeman2017 Article CreativityOfImagesUsingDigitalDocument15 pagesFreeman2017 Article CreativityOfImagesUsingDigitalJoan BryamNo ratings yet

- CriticalThinking Value PDFDocument2 pagesCriticalThinking Value PDFAnaNo ratings yet

- Creativity Research JournalDocument15 pagesCreativity Research JournalDelmy BlahhNo ratings yet

- Stil Cognitiv, CreativitateDocument13 pagesStil Cognitiv, CreativitateAndreea DemianNo ratings yet

- Creativity and Thinking PPT at Bec DomsDocument21 pagesCreativity and Thinking PPT at Bec Domssujal patelNo ratings yet

- Criticalthinkingpowerpoint 130327000622 Phpapp02 ( (Unsaved 304882360718287699) )Document16 pagesCriticalthinkingpowerpoint 130327000622 Phpapp02 ( (Unsaved 304882360718287699) )Younas BilalNo ratings yet

- Creative Mindsets: Measurement, Correlates, ConsequencesDocument10 pagesCreative Mindsets: Measurement, Correlates, ConsequencesVitor CostaNo ratings yet

- Oman 2013Document28 pagesOman 2013inyas inyasNo ratings yet

- Reliability and Validity: by Tayyeb RamzanDocument7 pagesReliability and Validity: by Tayyeb RamzanMaryam KhushbakhatNo ratings yet

- Makerspace RubricDocument4 pagesMakerspace Rubricapi-441559504No ratings yet

- Quantitative Research: by Unknown Author Is Licensed UnderDocument12 pagesQuantitative Research: by Unknown Author Is Licensed Underneil davidNo ratings yet

- Establishing Trustworthiness in Flexible Design Research PDFDocument6 pagesEstablishing Trustworthiness in Flexible Design Research PDFYinghua ZhuNo ratings yet

- Practica L Research 2Document22 pagesPractica L Research 2tan2masNo ratings yet

- Macbeth Advertisement Assessment Year 10 EnglishDocument10 pagesMacbeth Advertisement Assessment Year 10 Englishapi-365069953No ratings yet

- 01 - Research - Intro - HANDOUTDocument2 pages01 - Research - Intro - HANDOUTJOSEPH EARNEST TIEMPONo ratings yet

- Pnu AcesDocument3 pagesPnu AcesJoviner Yabres Lactam100% (1)

- Day 3 Week 2Document2 pagesDay 3 Week 2Kathleene AulidaNo ratings yet

- Thinking Skills and CreativityDocument9 pagesThinking Skills and CreativityArifNo ratings yet

- EPI 3.6 Qualitative ResearchDocument5 pagesEPI 3.6 Qualitative ResearchJoher MendezNo ratings yet

- Literacy Unit Plan - Carmen Morton SpreadburyDocument12 pagesLiteracy Unit Plan - Carmen Morton Spreadburyapi-480456754No ratings yet

- Authentic Assessment-2Document2 pagesAuthentic Assessment-2api-367267408No ratings yet

- PracRes Notes PPT 2 4Document5 pagesPracRes Notes PPT 2 4A - BUDY, Joaquin Benedict G.No ratings yet

- Sentimen Analis AppaisalDocument7 pagesSentimen Analis AppaisalNara AnindyaNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Inquiry and ResearchDocument16 pagesThe Nature of Inquiry and ResearchElenear De OcampoNo ratings yet

- Dimensions of Creativity in Secondary School High-Ability StudentsDocument9 pagesDimensions of Creativity in Secondary School High-Ability StudentsYULISA FERNANDA LUGO MARTINEZNo ratings yet

- Models of Ecological RationalityDocument16 pagesModels of Ecological RationalityTeresa DíazNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9Document3 pagesChapter 9ag.fitness.pt19No ratings yet

- Wayne AttoeDocument10 pagesWayne AttoeANURAG GAGANNo ratings yet

- Sel FesteemDocument4 pagesSel FesteemasribestariNo ratings yet

- Wang 2014Document11 pagesWang 2014karbonoadisanaNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Materials - HutchinsonDocument6 pagesEvaluating Materials - HutchinsonOrientación Juan ReyNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking Elements of Interior DDocument6 pagesCritical Thinking Elements of Interior DGlydel Vea AudeNo ratings yet

- MKT600-Assessment1 - Case Study Report-092018Document6 pagesMKT600-Assessment1 - Case Study Report-092018Anuja ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Marking Criteria, Taught PostgraduateDocument2 pagesMarking Criteria, Taught PostgraduateDaniel CastilloNo ratings yet

- Are You Positive?: - Elizabeth BuieDocument6 pagesAre You Positive?: - Elizabeth Buieapi-25894708No ratings yet

- Value Rubric PacketDocument18 pagesValue Rubric PacketnubiaNo ratings yet

- Class PresentationDocument7 pagesClass PresentationRitik YadavNo ratings yet

- Educational Evaluation WorkshopDocument17 pagesEducational Evaluation WorkshopPedro CairoNo ratings yet

- Aacu Value Rubrics Core CompetenciesDocument10 pagesAacu Value Rubrics Core Competenciessonia reysNo ratings yet

- Hypothesis Testing Reliability and ValidityDocument11 pagesHypothesis Testing Reliability and ValidityAkshat GoyalNo ratings yet

- Cropley 1999Document9 pagesCropley 1999Stella ÁgostonNo ratings yet

- C T Value R: Ritical Hinking UbricDocument3 pagesC T Value R: Ritical Hinking Ubricclaudina silvaNo ratings yet

- CTCTC DefinitionsDocument2 pagesCTCTC Definitionskitano4626No ratings yet

- History of Psychological TestingDocument20 pagesHistory of Psychological Testingrbungriano2737valNo ratings yet

- S216 FinalDocument7 pagesS216 FinalrudolNo ratings yet

- Critical Evaluation Tutorial UG UoLDocument18 pagesCritical Evaluation Tutorial UG UoLDrishna ChandarNo ratings yet

- A Mixed Methods Study On The Influence of Feedback Source On Creative Development in Middle ChildhoodDocument13 pagesA Mixed Methods Study On The Influence of Feedback Source On Creative Development in Middle Childhoodapi-536883471No ratings yet

- Deconstructing Product Design Exploring The Form, Function, Usability, Sustainability, and Commercial Success of 100 Amazing Products PDFDocument100 pagesDeconstructing Product Design Exploring The Form, Function, Usability, Sustainability, and Commercial Success of 100 Amazing Products PDFMontserrat CifuentesNo ratings yet

- AssessmentDocument2 pagesAssessmentMa Elena LlunadoNo ratings yet

- Miracle Worker EssayDocument2 pagesMiracle Worker Essayafhbfbeky100% (2)

- WorkExperience SrSec 2023-24Document27 pagesWorkExperience SrSec 2023-24Minecraft XboxNo ratings yet

- Hill (2009) Rebellious Pedagogy, Ideological Transformation, and Creative Freedom in FinnishDocument30 pagesHill (2009) Rebellious Pedagogy, Ideological Transformation, and Creative Freedom in FinnishKaty WeatherlyNo ratings yet

- EDCI616 - TEACHER LEADERSHIP TEXTBOOK - 2NDEdDocument256 pagesEDCI616 - TEACHER LEADERSHIP TEXTBOOK - 2NDEdErika MarinNo ratings yet

- Innovative ManagementDocument14 pagesInnovative ManagementFaisal IqbalNo ratings yet

- Innovation in Education PD50192Document22 pagesInnovation in Education PD50192Ancy davidNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1: Art Appreciation, Creativity, Imagination and ExpressionDocument8 pagesLesson 1: Art Appreciation, Creativity, Imagination and ExpressionOmar DulayNo ratings yet

- UNIT III - Lesson 2 Selection and Organization of ContentDocument5 pagesUNIT III - Lesson 2 Selection and Organization of Contentextra accountNo ratings yet

- Full Download Test Bank The New Leadership Challenge Creating The Future of Nursing 5th Edition PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Test Bank The New Leadership Challenge Creating The Future of Nursing 5th Edition PDF Full Chapterhenchmangenipapn50d100% (20)

- 10 Stories With LessonDocument14 pages10 Stories With LessonJudolyn TupagNo ratings yet

- City University of Hong Kong Course Syllabus Offered by School of Energy and Environment With Effect From Semester A 2018/19Document5 pagesCity University of Hong Kong Course Syllabus Offered by School of Energy and Environment With Effect From Semester A 2018/19محمد خالدNo ratings yet

- Swadhisthan ChakraDocument1 pageSwadhisthan Chakraevey_GNo ratings yet

- CWK Preliminary 1Document12 pagesCWK Preliminary 1Mohammad MohammadPourNo ratings yet

- Creative LeadershipDocument6 pagesCreative LeadershipRaffy Lacsina BerinaNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Test: Dimension - Oral Communication Competence 1 - ListeningDocument7 pagesUnit 5 Test: Dimension - Oral Communication Competence 1 - ListeningJuan Jesús Pesado del RíoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document19 pagesChapter 5firebirdshockwave100% (2)

- CREAM StrategyDocument8 pagesCREAM Strategynedcool2016No ratings yet

- IBM Unit 3 - The Entrepreneur by Kulbhushan (Krazy Kaksha & KK World)Document4 pagesIBM Unit 3 - The Entrepreneur by Kulbhushan (Krazy Kaksha & KK World)Sunny VarshneyNo ratings yet

- Using Tech Form 3Document11 pagesUsing Tech Form 3api-662490478No ratings yet

- SHS Handouts and Workshop Templates (Group 5) PEACDocument10 pagesSHS Handouts and Workshop Templates (Group 5) PEACGrace ManiponNo ratings yet

- Innovation CultureDocument42 pagesInnovation CultureezrreenNo ratings yet

- Decision Making ReportDocument27 pagesDecision Making ReportHarold Mantaring LoNo ratings yet