Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Macfarlane 1984

Macfarlane 1984

Uploaded by

Abdifatah MohamedOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Macfarlane 1984

Macfarlane 1984

Uploaded by

Abdifatah MohamedCopyright:

Available Formats

Africa's Decaying Security System and the Rise of Intervention

Author(s): S. Neil MacFarlane

Source: International Security, Vol. 8, No. 4 (Spring, 1984), pp. 127-151

Published by: The MIT Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2538566 .

Accessed: 13/06/2014 21:46

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Security.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africas Decaying S.NeilMacFarlane

Security System and

the Rise of Intervention

A fricahas neverbeen

freeof militaryintervention,1 but this formof behavior has become increas-

ingly common in recent years (see Table I). This suggests that intervention

is of increasing significanceas a problem of regional security,and invites

enquiryinto the causes and impactof thistrend.Most studies of intervention

in Africaview the issue fromthe perspectiveof East-West relationsand the

global balance or from that of policymakersin the interveningor in rival

states.2There is no doubt much of value in these approaches. Yet the dis-

cussion of interventionis incompletewithoutattentionto itsregionalcontext,

to its local origins and consequences. An understandingof these regional

aspects is importantnot only to those in Africawho feelits forcemost directly

and to those with an academic interest in African politics. It is also of

significanceto those scholars and policymakersconcerned with assessing its

effectson Westerninterestsand with developing policy responses to the use

of forcein the region.

In the preparationof this paper, I am indebted to ProfessorSamuel Huntingtonand Dr. Dov

Ronen of Harvard University'sCenter forInternationalAffairsand to ProfessorRobertJackson

of the Universityof BritishColumbia fortheircommentson previous drafts.The research was

conducted while the author was an Olin Fellow at the Center forInternationalAffairs,Harvard

University.

Relations,the Universityof

S.N. MacFarlaneis a ResearchAssociateat theInstituteof International

BritishColumbia.

1. For the purposes of this paper, interventionrefersto coercive militaryinvolvementin civil

or regionalconflictwhich is intended to, or does, affectinternalauthoritystructuresin the target

state. For a useful discussion of the definitionof intervention,see JamesRosenau, "Intervention

as a ScientificConcept," JournalofConflictResolution,Vol. 22, No. 2 (1969), pp. 149-171.

2. See, forexample, ArthurJ.Klinghoffer,The AngolanWar: A Studyin SovietForeignPolicyin

theThirdWorld(Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1980); Gerald Bender, "Kissingerin Angola: Anatomy

of a Failure," in Rene Lemarchand, ed., AmericanPolicyin SouthernAfrica:The Stakesand the

Stances(Washington: UniversityPress of America, 1981); Colin Legum, "Angola and the Horn

of Africa,"in Stephen Kaplan, ed., DiplomacyofPozwer: SovietArmedForcesas a PoliticalInstrument

(Washington: Brookings, 1981); David S. Yost, "French Policy in Chad and the Libyan Chal-

lenge," Orbis,Vol. 26, No. 4 (Winter1983), pp. 965-998; and Daniel Bach, "La France en Afrique

Subsaharienne: Contraintes Historiques et Nouveaux Espaces Economiques," Unpublished

manuscriptdelivered to a colloquium of the Association Francaise de Science Politique, May

26-27, 1983.

$02.50/1

Security,Spring 1984 (Vol. 8, No. 4) 0162-2889/84/040127-25

International

(C 1984 by the Presidentand Fellows of Harvard College and of the Massachusetts Instituteof Technology;

127

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

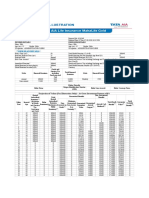

Table I. Interventionsin AfricaSince 1975.

Venue Year Intervener Circumstance

1. Angola 1974-76a Zaire pro-FNLA

U.S. pro-FNLA,UNITA

Republic of pro-FNLA,UNITA

South Africa

Cuba (with Soviet pro-MPLA

support)

2. Zaire (Shaba) 1977 Morocco (with pro-Zairean government

French

logistical

support)b

3. The Horn 1977-78 Somalia pro-WSLF

South Yemen pro-Ethiopiangovernment

Cuba pro-Ethiopiangovernment

U.S.S.R. pro-Ethiopiangovernment

4. Mauritania 1977-78 POLISARIO anti-government

Moroccoc pro-Mauritanian

government

France pro-Mauritanian

government

5. Zaire (Shaba) 1978 France pro-Zairean government

Belgium pro-Zairean government

6. Chadd 1978 France pro-Chadian government

Libya pro-AcylAhmat

7. Uganda 1979 Libya pro-Ugandan government

Tanzania pro-Uganda National

Liberation Army

8. Chad 1979 Nigeria peacekeeping

Libya anti-government

9. Tunisia 1980 Libya anti-government

10. Chad 1980 Libya pro-Goukouni/Acyl/Kamony

11. Gambia 1981 Senegal pro-Gambian government

12. Chad 1981 OAU peacekeeping

13. Zimbabwe 1982 Republic of destabilization of

South Africa government

14. Mozambique 1982 Republic of destabilization, pro-

South Africa Mozambique

15. Chad 1982-83 Libya pro-Goukouni

France pro-Habr6

16. Somalia 1982 Ethiopia pro-SSDF

a

Cuban troops remain in Angola, while South Africanincursions persist.

b

Since the FLNC (Frontde Liberation Nationale Congolaise) apparentlyacted independently,

and is comprised of Zairois, it is not listed as an intervener.

c Morocco's occupation of the Western Sahara is not listed as an intervention,as King Hassan

was not intrudingon one side or another of an internal dispute. His intentwas not to

affect the internal politics, such as they were, of the former Spanish Sahara, but to

extinguish them.

dChad is entered on five occasions, because in each case the militaryintrusions were

discreet events.

Abbreviations: FNLA-Frente de Libertacao Nacional de Angola

UNITA-Uniao para e Independencia Total de Angola

MPLA-Movimento Popular de Libertacao de Angola

WSLF-Western Somali Liberation Front

POLISARIO-Popular Front for the Liberation of the Saguia el-Hamra and

Rio de Oro

OAU-Organization of AfricanUnity

SSDF-Somali Salvation Democratic Front

MRM-Mozambique Revolutionary Movement

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa'sSecuritySystemj 129

With these concerns in mind, this paper addresses the regional causes of

interventionand, fromthe perspectiveof Africanstates,what its implications

are for regional security.3The analysis focusses on member states of the

Organization of AfricanUnity (OAU), since the Republic of South Africais

in no meaningfulsense a member of the African"society of states." It may

be viewed instead as an actor on the fringesof, but externalto, the African

system,whose foreignpolicy has importantconsequences forthe securityof

actors withinthe regional system.

The paper argues thatinterventionis at least as much a symptomof more

basic regional problems (politicaland social fragmentation, economic decay,

progressive differentiation in the distributionof power) as it is a cause of

regional instabilityin its own right.Generalization about the impact of in-

terventionon African politics is difficult,and much of the conventional

wisdom on this subject does not stand close examination. Recent trends in

the interstatepolitics of the region and in regional defense spending do,

however, suggest that the growing incidence of interventionencourages

expansion of defense establishmentsin the region. In addition,itboth reflects

and fostersan erosion of regional norms governinginterstatebehavior. Fi-

nally, it tends to complicate conflictresolutionby embroilinglocal disputes

in extra-regionalrivalries.

TheRegionalConditionsofIntervention

In accounting for the increasing frequencyof interventionin the region, a

numberof externalfactorsare of greatimportance,most notablythe transfer

of superpower competitionin the period of detente to the peripheryof the

internationalsystem,the subsequent deteriorationin relationsbetween East

and West, and the growing insecurityof the principalmilitarypower in the

Sub-Saharan area, South Africa.But this increase cannot be fullyexplained

withoutattentionto conditions in the targetenvironment.In the firstplace,

such factorsfail to account for what is the most rapidly growing type of

intervention-that undertaken by African states themselves. Beyond this,

instabilityin the region favors interventionby both regional and extra-re-

gional actors fortwo reasons. First,states which are divided internallyhave

3. For a discussion of the meaning of regional securityfroman Africanperspective,see S. Neil

MacFarlane, "Regional Securityand AfricanIntervention,"International forthcoming.

Affairs,

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International

Security| 130

difficultyin mounting resistance to intrusionby outsiders. Second, parties

to internalconflictssolicitoutside assistance against theirrivals. When their

survival is threatened, they seek escalation of their external benefactor's

involvement. In this sense, internal conflictprovides an entry point for

outsidersinterestedin influencingthe policy choices of the state in question.

It may also entail perceived commitmentswhich are difficultto disavow

when a local clientis in trouble.In this context,interventionin Africais not

so much a cause of regional insecurityas it is a manifestationof more

profoundproblems. There are at least threefundamentalproblemsof African

security,leaving aside the issue of apartheid in South Africa,which is not,

strictlyspeaking, internalto the system.

The firstis political fragmentation.The profound causes of communal

conflictin Africalie to some extentin ethnicand religiousdifferenceswhich

predate the colonial period. Chad here provides an example. Before the

French arrived, Chadian Arabs had for centuriesraided black Sara villages

in the south forslaves, while the Toubous of northernChad habituallyraided

Arab trans-Saharancaravans. The arbitrarycharacterof the colonial frontiers

established in the late 19thcenturyin many cases exacerbatedthese tensions

or created new ones, by lumping togetherrival groups in single polities and

by splittingethnic groups between jurisdictionsleaving innumerablepoten-

tial irredenta. One might cite here the inclusion of large Arab and black

populations in the Sudan, and the combinationof Hausa and Ibo in Nigeria.

The Kikongo desire to reestablish the precolonial kingdom of Bakongo out

of portionsof southwesternZaire and northernAngola or the Somali designs

on Kenya, Ethiopia, and Djibuti may be cited as examples of irredentist

revisionism stemming from the splittingof single ethnic groups. Finally,

colonial rule had a differentiated impact on the various ethnicgroups within

single colonies. Some groups had greateraccess to public goods provided by

the colonial powers, and some adapted more quickly than others to the

dominant colonial structure.Such groups benefiteddisproportionatelyfrom

education and were well placed to occupy positions in the colonial service

and, later, in the civil services, armies, and politicalelites of the new states.

This inequity created resentmentson the part of those leftbehind, particu-

larlywhen the individuals occupyingthese new positionsdistributedbenefits

in such a way as to favortheirown kinship groupingsand used theirpower

to exploitotherethnicgroups. Again, Chad is a good example, as is Nigeria.

Despite this legacy, there were several apparentlypromisingmovements

towards national integrationin the 1960s and early 1970s. Ghana under

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa'sSecuritySystem| 131

Nkrumah (with some reservationswith respect to his treatmentof the As-

hanti) and Nigeria in the period of national reconciliationand growthfollow-

ing the civilwar are examples. But with the passage of time,it is increasingly

clear that the dominant trend in African domestic politics is towards the

disintegrationof the states created upon the departure of the European

colonialists. Evidence forthis may be seen in the continuingsectarianprob-

lems and north-south conflictin the Sudan; in the failure in Ethiopia to

extinguishthe Eritreanand Tigrean insurgenciesdespite massive application

of force;in the continuingethnicconflictin Chad; in the failureof non-ethnic

parties to emerge in Nigerian politics; in the persistentsecessionism of the

Lunda in Shaba evident in the popular response to the arrivalof Front de

LiberationNationale Congolaise (FLNC) forcesfromAngola in 1977 and 1978;

in ethnic strifeamong Kikongo, Kimbundu, and Ovimbundu in Angola; in

the growing violence between Shona and Ndebele in Zimbabwe; in unrest

among the Baganda in Uganda; in continuingKikuyu-Luo tensionsin Kenya;

and so on. There is hardlya state in black Africawhich appears more viable

today than it did on the eve of independence. Several appear much less so,

the unifyinginfluence of anticolonialismlong ago having waned and the

threatof neocolonialism being too nebulous to arouse popular enthusiasm.

Even those statesusually citedas being based upon a strongnationalidentity,

Somalia being a case in point, are rivenwith ethnicallyand regionallybased

strugglesforpower and position and forthe meager materialrewards avail-

able to those who possess them. Externaloppression has been replaced with

oppression by indigenous clan and tribalgroupings. The consequences are

almost inevitablyfissiparous.

This political fragmentationis exacerbated by the catastrophiceconomic

performanceof much of the region in the 1970s and early 1980s. At present,

almost two-thirdsof the states fallinginto the World Bank's "low income"

(per capita income less than $370 a year) categoryare African.GNP growth

per capita forSub-Saharan Africa(including rapidlygrowingcountriessuch

as Nigeria, Ivory Coast, and Kenya, but excluding South Africa) was .8

percentper year in the 1970s, down from1.3 percentin the previous decade.

The World Bank notes that output per person grew more slowly in Africain

the 1970s than in any other region. Seven countriesin Africahad negative

growthin GNP. Eight more had negative per capita rates of growth.

Volumes of exports in Sub-Saharan Africa fell at an annual rate of 1.6

percent (median for countriesin the region excluding South Africa)during

the decade. This fallin volume was accompanied by fairlyrapid deterioration

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Security1132

International

in the termsof trade forAfricanoil importerslate in the decade (a negative

shiftof approximately8 percentin 1978-1980). Mineral exporterswere par-

ticularlyhard hit during the decade, despite a number of good years. Their

termsof trade dropped between 1970 and 1979 by an average of 7.1 percent

per year. The softeningof oil markets in the last two years has extended

these effectsto Africanoil exporterssuch as Nigeria, Gabon, and Angola.

The financialconsequences of these trendsare severe. Currentaccount def-

icits in the region climbed from $1.5 billion in 1970 to $8 billion in 1980.

Externalindebtedness went from$6 billion to $32 billion between 1970 and

1979. The situationhas, if anything,deterioratedfurthersince 1979.

Food productionin the 1970s in Sub-Saharan Africagrew in absolute terms

by some 1.5 percent per year, but, given the regional population growthof

2.7 percent annually, the per capita growth rate in food production was

negative, dropping at a rate greaterthan 1 percenta year. At present, only

six or seven countries in Africa are self-sufficient in food.4 Commentaries

fromaround the continentstressendemic shortagesof staples, both in urban

areas and in the hinterland,and severe inflationin food prices.5

Much of this poor economic record may be explained in terms of prior

underdevelopmentwithattendantundercapitalization,absence ofsubstantial

domesticmarkets,and shortagesof technicallyskilledindigenous personnel,

the legacies of the precolonial and colonial eras. The inefficiencyof many

foreignassistance programs-the result of poor planning and coordination,

insufficientattentionto characteristicsof the local environmentand the con-

straintsthese impose on the development effort,and bureaucratization-is

another importantfactor.A thirdis the relativelylow level of the flow of

private capital to Africa,and the outward flow of Africancapital to safer

havens. A fourthis the crippling effectof OPEC price increases on the

region's oil-importingeconomies. In addition, the incompetence, irrespon-

sibility,and acquisitiveness of many of the continent'sleading political fig-

ures and of the elites fromwhich they emerge and which they serve cannot

be ignored.

4. The above data are taken from World Bank, AcceleratedDevelopmentin SubsaharanAfrica

in food, see also J. Gus

(Washington: World Bank, 1981), pp. 3, 18, 19, 45. On self-sufficiency

Liebenow, "AfricanPolicy in Africa:The Reagan Years," CurrentHistory,Vol. 82, No. 482 (1983),

p. 98.

5. Gerald Bender, "The Continuing Crisis in Angola," CurrentHistory,Vol. 82, No. 482 (1983),

p. 128; W. Skurnik, "Continuing Problems in Africa's Horn," in ibid., p. 121; and Jon Kraus,

"Revolution and the Militaryin Ghana," in ibid., pp. 116, 131.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa'sSecuritySystem| 133

In periods when the pie is growing, it is possible to contain communal

and class tensions by sharingout the benefitsof development. When the pie

is not growing or is shrinking,while the numbers of those tryingto eat it

are expanding, communal conflictover resources becomes an ever more

serious problem.

This may be of greatest import in those states which have had some

economic success, as subsequent failurenecessarilyinvolves the disappoint-

ment of expectationsformedin the good years. In this context,Nigeria, once

considered one of the region's few success stories,seems at the moment to

be in a particularlyparlous state, given its fallingoil revenues, government

expenditurecutbacks,and risingunemployment.The recentreductionin the

price of Nigerian oil in violation of OPEC price guidelines is an indicationof

its distress,as are the expulsion early this year of 1.5-2 millionillegal aliens,

and the recent cutoffof scholarship funds to between 15,000 and 20,000

students in the United States.

The link between internalcommunal conflictand externalinterventionis

clear throughoutthe region-the Zairean involvementin northernAngola in

support of Holden Roberto's FNLA, the Somali link with theirethnic kin in

the Ogaden, the Ethiopian exploitationof clan rivalriesin Somalia, and the

Libyan connectionwith Chadian Arabs all being cases in point. Of the eleven

venues of interventionsince 1974 listed in Table I, interventionis to some

extent linked to ethnic rivalriesin nine. Cross-frontierethnic or religious

affinitiesprovide both opportunityand justification(however spurious) for

militaryintrusionsby contiguous states. The ethnic and communal dimen-

sion is one aspect of the broader principle that political instabilitywithin a

given state encourages interventionby externalactors with an interestin the

outcome of its political process (as with Senegalese interventionin behalf of

Gambia's PresidentJawarain 1981 and Tanzanian interventionin Uganda in

1979).

But this is not the only causal link between politico-economicdifficulties

and intervention.Those sufferingfrominternalinstabilityare not only po-

tential targets. They are also potential interveners,in that regimes often

attemptto compensate for their incapacity to cope with pressing internal

problemsand fortheirillegitimacyin the eyes of theirown publics by success

in foreignpolicy. The Moroccan involvementin the WesternSahara is a case

in point. One could also cite here the impact of Somalia's irredentistforeign

policy in divertingthe public's attentionfromsuccessive regimes' failureto

stimulate sustained development, the irrationaland wasteful character of

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International

Security| 134

much of the country's economic planning, and the obvious inequities in

allocationof public goods and distributionof rewards. A thirdexample might

well be the militantPan-Islamic policy of Colonel Qaddafi-the behavioral

manifestationsof which are the repeated invasions of Chad, the sponsorship

of subversionin Tunisia, Senegal, and Nigeria,and the defense ofIdi Amin-

one consequence of which is to defuse internal opposition to his rule. A

fourthis Mobutu's occasional manipulation of the Bakongo issue and his

attemptsto annex Cabinda.

Beyond this, regimes may attemptthroughinterventionsof theirown to

preempt or to terminate effortsby outsiders to take advantage of or to

exacerbate internal instability.Here one can cite Ethiopian incursions into

Somalia or the Ethiopian support of Ansari dissidents in Sudan. An example

on the fringeof the system is South Africandestabilizationof Angola, Le-

sotho, Zimbabwe, and Mozambique through direct militarypressure and

throughits support of insurgentgroups operatingin these countries.6

The thirdfactorwhich deserves mentionis the growingregional disparity

in militaryand other forms of power. I.W. Zartman, in a seminal article

discussing the Africanstates system,described the mid-1960sregional con-

figurationof power as one of highlydiffusedand unhierarchicaldistribution

at uniformlylow levels.7 Data fromthe 1960s concerningforcelevels, arms

procurement,and militaryexpenditures support this characterization.8The

past decade, however, has witnessed the emergenceof a number of regional

powers whose military(and in some cases economic) capacities faroutstrip

those of most states in the region. Libya, Ethiopia, Algeria, Morocco, and

Nigeria are all examples of the militarydimension of this imbalance. This

differentiation in militarycapabilitiesrendersit increasinglypossible forthese

states to contemplateinterventionin the affairsof neighboringstates. Libya

has displayed a pronounced tendencyto employ its new militarypower and

the financialresources lyingbeneath it to acquire a position in regionalaffairs

commensurate with its inflated self-image. Morocco has used its military

capabilities to absorb the economically importantsections of the Western

6. For an account of the South Africanpolicy of destabilizationin southern Africa,see Chris-

topherCoker, "South Africa:A New MilitaryRole in SouthernAfrica,1968-1982," Survival,Vol.

25, No. 2 (1983), pp. 62-64.

7. I. William Zartman, "Africaas a Subordinate State System in InternationalRelations," Inter-

nationalOrganization,Vol. 21, No. 3 (1967), p. 550.

8. Cf. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency, WorldMilitaryExpenditures and ArmsTransfers,

1964-1973 (Washington: ACDA, 1976).

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa's

Security 1135

System

Sahara and to take on the role of regional policeman in the Shaban crises.

Algeria, meanwhile, has financed and provided sanctuary, training,and

materielto POLISARIO, which ituses as a proxyin resistingwhat itperceives

to be Moroccan expansionism. Ethiopia has recentlyused forceagainst So-

malia in order to destabilize the Siad Barre regime,attemptingto remove its

principal subregional rival. Nigeria, finally,recentlydeployed its forces in

Chad, not only as a contributionto regional conflictresolution,but in order

to influencethe course of the Chadian conflictin a manner consistentwith

its national interest.In otherwords, all of these new regionalpowers display

a willingness to use theirstrengthto furthertheirperceived interests.

To sum up, the weakness of state structuresand, underlyingthis, the

frailtyof national consciousness in the face of subnational ethnicchallenges

are criticalpermissive conditions for interventionin Africa. They are also

active stimuliof intervention.As the economic situationworsens and com-

munal conflictintensifies,these effectsstrengthen.The growingdisparityof

militarypower in the regiongives some regionalactorsa capacitywhich they

did not previously possess to respond to or take advantage of these condi-

tions or to pursue their intereststhrough the projection of force. In this

sense, the growing frequencyof interventionin the region is a consequence

of the continent'sgrowing political and economic crises and of the increas-

inglyhierarchicalcharacterof Africaninternationalpolitics.

TheImpactofIntervention

on African

Regional

Security

From the point of view of member states of the OAU, the common denom-

inatorof regional securitypresumablyconcerns the capacity of states in the

region to pursue their core values without external hindrance. While any

attemptto enumeratethe core values of a region as culturally,economically,

and politicallydiverse as OAU Africawill of necessitybe somewhat arbitrary,

most politicallyaware people in the region and a majorityof Africangovern-

ments would probablyput forwardsets of values approximatingthe follow-

ing: internalpolitical stability9and national integration;self-determination

9. Stabilityis here defined as a situation in which a regime or political system is free from

serious challenge (originatingwithin the country)to its existence, as it attemptsto cope with

and adapt to evolving internaland externalpolitical realities. For a discussion of the meaning

of stability,see Samuel P. Huntington, "Remarks on the Meaning of Stabilityin the Modern

Era," in Seweryn Bialer and Sophia Sluzar, eds., Strategies

and ImpactofContemporary Radicalism:

Radicalismin theContemporary Age, Vol. 3 (Boulder, Colo.: Westview, 1977).

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Security1136

International

and the consolidation of the externalsovereigntyof existingterritorialenti-

ties; and economic development.10

Within the region, governments and political commentatorsfrequently

condemn interventionin an undifferentiatedfashion, maintainingthat its

impact on regional securityis negative.1"It is itselfa securityproblem rather

than a solution to problems of security.This conclusion is apparentlybased

upon several implicit or explicit judgments with respect to the effectof

externalmilitaryinterferenceon the values enumeratedabove: thatinterven-

tion both prolongs and intensifiesthe conflictwhich provoked it, increasing

the number of casualties and refugees and the level of physical destruction

in the targetenvironment;thatit therebyjeopardizes economic development;

that it erodes national sovereignty;and that it is politicallydestabilizingfor

the target.

This assessment is reflectednot only in attitudes towards intrusionsby

non-Africanactors,but in prevailingAfricanopinion even when the intrusion

is undertakenby an Africanactor in pursuit of objectiveswhich enjoy wide-

spread sympathyin the region. The Tanzanian interventionin Uganda in

1979 in response to Ugandan militaryprovocations and in order to remove

a regime widely considered to be destabilizingin the regional context is a

case in point. The action met with widespread condemnation and received

almost no support at the Monrovia OAU summitlater in the year.12

This rejectionin principleof interventionreflectsthe jealousy with which

the attributesof internaland externalsovereigntyare guarded by stateswhich

have only recentlygained theirindependence. The implicationinherentin

foreigninterventionthat the targetstate is incapable of managing its own

affairsor that it is a neocolonial appendage of an outsider is particulary

noxious in these circumstances.This attitudetowards interventionalso in-

10. For a similarcharacterizationby an Africanstatesman,see the speech of General Obasanjo

at the KhartoumOAU summitin 1978, reprintedin Survival,Vol. 20, No. 6 (1978), pp. 268-269.

See also I. William Zartman, International Relationsin theNew Africa(Englewood Cliffs,N.J.:

PrenticeHall, 1966), Chapter 4, and in particularpp. 149-151.

11. The clearest indications of this regional assessment may be found in various resolutionsof

OAU summits, such as "On Interferencein the Internal Affairsof African States" (1977),

reprintedin AfricaContemporary Record(1977-1978) (New York: Africana,1978), p. C4; and "On

MilitaryInterventionsin Africaand on Measures to Be Taken against Neocolonial Manoeuvres

and Interventionsin Africa,"AfricaContemporary Record(1978-1979), p. C19. Nolutshungu refers

in this context to a "reflexand often effeteimperativeagainst intervention"among African

states. Sam Nolutshungu, "AfricanInterestsand Soviet Power," SovietStudies,Vol. 24, No. 3

(1982), p. 405.

12. For an account of the Monrovia debate on Uganda, see Colin Legum and Zderek Cervenka,

"The OAU," in AfricaContemporary Record(1979-1980), pp. A61-A62.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa'sSecuritySystem1137

dicates an awareness of the weakness of national cohesion characteristicof

Africanstates and, consequently,of theirhigh susceptibilityto foreignpen-

etration.Finally, it is in some respects a legacy of early post-independence

crises in Africa (e.g., the Congo) where external interventiondrew into

question the degree, indeed the reality,of Africanindependence, entangled

Africanconflictsin East-West disputes, and was perceived to have length-

ened and intensifiedlocal hostilities.

None of the generalizationsupon which this negative assessment is based

stands up to close examination. Moreover, several are rejected, in specific

situationswhere national interestsor ideological commitmentsare at stake,

by Africanstates which otherwisesubscribeheartilyto the condemnation of

interventionin Africanaffairs.

INTERVENTION AND THE SCOPE OF LOCAL CONFLICT

The argument concerning interventionand the intensityand duration of

conflictis as follows. In theory,the introductionof well-equipped units of

an external power increases the quantityof firepowerdeployed and often

altersthe qualityof conflictsthroughthe deploymentof technologicallymore

sophisticated weapons systems. Moreover, such intrusions can prolong a

conflict,in thatappeals formore considerable support oftencome fromlocal

actors close to exhaustion. Finally,interventionmay bring counterinterven-

tion in support of other parties to the conflict.The cycle of intervention,

counterintervention, and escalation in the Angolan conflictis well known. It

is quite plausible that the result was a far higher intensityof conflictthan

would otherwise have obtained. In Chad, Libyan interventionand the con-

sequent competitive involvement of Sudan, Egypt, and, indirectly,the

United States in support of Hissene Habre significantly enhanced the military

capabilitiesof local actors and widened the scope of the conflict.

But thereare also cases in which interventionat a level sufficientto deter-

mine the outcome of a conflictterminatedhostilitiesor drasticallyreduced

their scale far earlier than would otherwise have been the case. In such

instances, it mightwell be asked whether a short relativelyintense conflict

was not preferablein termsof totalnumbersof militaryand civiliancasualties

and numbersof displaced persons and of the degree of disruptionof national

life,to a prolonged conflictat a lower level. In Angola, forinstance, thereis

good reason to believe that,once the Alvor Accords collapsed in early 1975,

conflictbetween the threeliberationmovementsand the ethnicgroups sup-

portingeach one would have dragged on more or less indefinitely.In the

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International

Security1138

Horn, Soviet and Cuban assistance to the Ethiopians broughtthe 1977-1978

Somali-Ethiopian conflictto an end farearlierthan was likelyin the absence

of thisintervention.Soviet bloc logisticalsupportalso enabled the Ethiopians

to contain the Eritreaninsurgencyat a much lower level than would other-

wise have been possible. Generalizationabout interventionand the intensity

and duration of conflictis, therefore,suspect.

INTERVENTION AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

The argument concerning effectson economic development derives from

that with regard to the intensityand duration of conflict.The more intense

a civil war is, the greater the disruption of agricultural,commercial,and

industrialactivity.But ifthe assumption concerningthe relationshipbetween

externalparticipationand the intensityand duration of conflictis question-

able, so too are its implications concerning the effectsof interventionon

economic activity.

In specificinstances, the effectsof interventionon economic activitycan

cut eitherway. In Angola, forinstance, the South Africanincursionin 1975

resultedin the miningof most roads in southernAngola and in the destruc-

tion of almost everybridge in thatpart of the country.CurrentSouth African

support of UNITA allows that group to attack the Benguela railroad with

impunity. This deprives the Angolans of a vital transportarteryand an

importantsource of foreignexchange, the railroadin bettertimes servingas

a major conduit forZairean and Zambian copper. South Africanattacks on

Kassinga, ostensiblydirectedat SWAPO camps in the area, have prevented

the reopening of the iron mines there, with the result that Angola, once a

major producer of iron ore, now produces and exportsnone. South African

militaryactivityhas forced Angola to devote more than 50 percent of gov-

ernmentexpenditureto defense. Coker has argued in thiscontextthatSouth

Africa'smain concern in Angola is not the support of Savimbi's attemptsto

unseat the MPLA, but the economic dislocation of Angola.13

On the otherhand, Gulf's oil productionfacilitiesin Cabinda survived the

1975-1976war and subsequent unrestbecause theywere protectedby Cuban

troops. French and Moroccan interventionin Mauritania in 1977-1978 in

response to POLISARIO guerrillaactivityin all likelihood prevented serious

13. Coker, "South Africa,"p. 62. On the economic effectsof South Africanmilitaryincursions

into Angola, see also Keesing'sContemporaryArchives(1982), p. 31419; and AfricaConfidential,

Vol. 22, No. 9 (1981), pp. 2-3.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa'sSecuritySystem1139

and prolonged disruptionof iron ore productionat Zouerate, the export of

which is Mauritania's major source of foreignexchange.14The presence of

French troops in Djibuti and the virtualcertaintythat theywould intervene

activelyif the governmentof that countrywere seriously threatenedfrom

withinor withoutcreatea favorableclimateforthe foreignprivateinvestment

the governmentis attemptingto attract.15

In other cases, interventionhas no obvious economic effects.Here one

could cite Chad, where what littleeconomic activitythere had been in the

north and center of the country had been so disrupted prior to Libyan

interventionthat the Libyans, even had they desired to do so, could inflict

littledamage. The production in the south of cotton, the country's major

export crop, was little affectedby the Libyan action of 1980-1981. Again,

therewould not seem to be any justificationforbroad generalizationat this

level about the impact of intervention.

INTERVENTION AND SOVEREIGNTY

The view thatinterventioncompromisesnational sovereigntyand self-deter-

minationrests on the argumentthat intrusionin behalf of a partyto a civil

war createsa relationshipof dependency such thatthelocal clientis incapable

of independent action in internaland internationalaffairswhere his interests

or preferencesdiverge fromthose of his patron. In otherwords, intervention

constitutesa new kind of colonialism.

This may be true in some instances. French militaryinterventionin Africa

comes quicklyto mind here, though it is probable thatpoliticaland economic

ties are far more importantin accounting for dependency in much of fran-

cophone Africathan is Frenchmilitaryactivity.But thiseffectof intervention

is by no means necessary. Britishinterventionon behalfof Nyererein 1964,

forexample, broughtlittlein the way of politicalreliability.One year later,

Tanzania broke relations with Great Britainover Rhodesia's unilateral dec-

larationof independence.

Nor is it absolute. Both Angola and Ethiopia are governed by regimes

which have benefitedconsiderablyfromCuban interventionwith substantial

Soviet support. While theyboth display a tendencyto support the U.S.S.R.

on issues which are to them peripheral-for example, their voting on the

14. See StrategicSurvey(1979) (London: InternationalInstituteforStrategicStudies, 1980), pp.

93, 96.

15. See Skurnik,"Continuing Problems in Africa'sHorn," p. 123.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International

Security1140

Afghan and Kampuchean issues at the United Nations-on issues more

central to their interests,they show considerable independence of mind.

Angola has rebuffedSoviet requests forbases and cooperates with the West-

ern Contact Group's effortsto resolve the Namibian question.16Ethiopia

refuses to compromise on the Eritreanissue, engages in interventionof its

own in Somalia, and resists Soviet pressure to restructureits political insti-

tutionsalong more ideologicallyacceptable lines.17

Nor is such influence permanent. The removal or disappearance of the

threatoccasioninginterventionremovesthe source ofa regime'sdependence,

weakening the basis of influence.The case of Britishinterventionin Tangan-

yika again comes to mind. Elsewhere, it is probable that an accommodation

between South Africa and Angola would reduce considerably the level of

Cuban and Soviet influencein Angola, a large part of which is derived from

the protectionprovided to the Angolan regimeby these two powers against

South Africanaggression and sponsorship of UNITA guerrillas.A settlement

of differencesbetween the MPLA and UNITA would reduce this influence

further.The availabilityof alternativesources of external support has the

same effect,as is evident in Egyptianbehavior in the aftermathof the 1973

war, or in Goukouni's foreignpolicy in the aftermathof Hissene Habre's

expulsion from Chad by Libyan troops in late 1980. The improvementin

Franco-Chadian relations in the summer of 1981 made it possible for Gou-

kouni to request the withdrawalof Libyan forces.Along similarlines, it could

be argued that a more receptive American attitudeto overturesfromboth

Angola and Ethiopia could do much to underminethe position of the Soviet

Union in both these countries.

Moreover, interventionmay preserveand enhance sovereigntyratherthan

eroding it. Soviet-Cuban interventionmaintained the external sovereignty

and territorialintegrityof Ethiopia in the face of Somali invasion. It is prob-

16. On the Angolan attitudetowards Soviet bases, see JohnMarcum, "Angola," in Gwendolyn

Carter and PatrickO'Meara, eds., SouthernAfrica:The ContinuingCrisis (Bloomington:Indiana

UniversityPress, 1979), pp. 193-194. DmitriVolsky, "Local Conflictand InternationalSecurity,"

New Times,No. 5 (1983), p. 5, gives a succinctSoviet view of the contactgroup's initiativeson

Namibia.

17. There is ample reason to doubt Soviet complicityin the Ethiopian intrusionsinto Somalia,

therebyriskingthe alienation of otherAfrican

as they constitutean assault on Somali territory,

states. On Ethiopian independence fromthe Soviet Union in internalpolicy, see Paul Henze,

"Communism and Ethiopia," Problemsof Communism,Vol. 30, No. 3 (1981), pp. 63-64; Oye

Ogunbadejo, "Soviet Policies in Africa," AfricanAffairs,Vol. 79, No. 316 (1980), p. 125; and

Nolutshungu, "AfricanInterests,"p. 410.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa'sSecuritySystem1141

able thattheirinterventionin Angola preventedor postponed thatcountry's

eventual disintegrationor dismemberment.Finally,even those in the region

most adamant in theiropposition to interventionin Africanaffairsgenerally

accept that the involvementof externalactorsin the strugglefor"liberation"

can furtherthe cause of self-determination.18

It is clear in this context that underlyingthe general condemnation of

interventionmentioned above is a wide range of mutually incompatible

positions on interventionin Africanconflict.The 1978 Khartoum summitof

the OAU, which dwelt at length on the subject of intervention,was split

between, on the one hand, moderate and conservativegovernmentswhich

supported actions such as those taken by France, Belgium, and Morocco in

Shaba to preserve a weak regimeagainst a "radical" opposition, and, on the

other, "progressive" regimes which displayed great reluctanceto condemn

Soviet and Cuban activitiesin Africawhile bitterlycriticizinginvolvementby

Western powers and the position of those Africanstates which cooperated

with France in Shaba and in subsequent proposals fora "Pan-Africanpeace-

keeping force." In this instance too, then, thereis littlebasis fora sweeping

condemnation of intervention.

INTERVENTION AND POLITICAL STABILITY

Finally,thereis the question of politicalstability.A look at cases of interven-

tionin Africasuggests that,in the shortterm,interventionmay be stabilizing

or destabilizingin intentand consequences. By way of illustration,there is

littleto argue with in the assertionthatSouth Africaninterventionin Angola

since 1976, and in particularits support of UNITA, has been destabilizingin

both intentand consequences, creatingsevere difficultiesforthe regime in

the Bie, Moxico, Cuando Cubango, and Cunene districts,fosteringdissension

withinthe ranks of the MPLA, and impeding the government'sattemptsto

meet the needs of the population and to integratethe diverse ethnic groups

inhabitingthe countryinto one nation.

By contrast,the recent Ethiopian incursionsinto western Somalia in sup-

port of the Somali Salvation Democratic Frontwere intended to undermine

the Siad Barre regime, but in all likelihood have had the opposite effectby

mobilizingnationalist support behind the totteringBarre and inducing the

northernIsaaq clans to reduce theirpressure on the centralgovernment.

18. Cf. the Nigerian position as elaborated by General Obasanjo in the speech cited in note 10.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Security1142

International

Anothercontrastingexample is thatof Soviet-Cuban interventionin Ethio-

pia, which was intended to prop up the socialistEthiopian governmentand

did just that. The intrusionneutralized the principal externalthreatto the

Dergue, provided the Ethiopians with the means to contain the Eritreanand

Tigrean insurgencies,and gave the regime the breathingspace necessary to

consolidate its hold on power in the capital and in centralEthiopia.

In the longer term,thereare good reasons to expect thatmilitaryinterven-

tion is unlikelyto enhance a targetstate's stability.While interventionmay

bring militaryvictoryforone of the parties to a civil or regional dispute, so

long as the political and social roots of the conflictwhich occasioned inter-

vention are not addressed, the solution will remain at best a temporaryone

and one which is fraughtwith dangers of deeper entanglement for the

externalactor.19

Externalinterferencemay in fact reduce the likelihood of conflictresolu-

tion. In the Angolan, Ethiopian, and Chadian cases, externalassistance con-

vinced its internalbeneficiariesthat negotiationwith their opponents was

unnecessary, that militarymeans were sufficientto resolve the civil conflicts

in which they found themselves embroiled. In Angola, the Soviet-Cuban

presence has apparently strengthenedthe MPLA's resolve not to share po-

liticalpower with UNITA. In Ethiopia, and despite Soviet and Cuban advice

to negotiate with and to grantlimitedautonomy to the Eritreans,20 military

interventionhas made it possible forthe regime to survive withoutcompro-

mise and to pursue indefinitelyits campaign against the Eritreaninsurgency.

In Chad, Libyan and OAU interventionin behalf of Goukouni Oueddei's

transitionalgovernmentconvinced Goukouni that he could consolidate his

controlof Chad withoutany attemptto achieve a politicalsolution involving

his principalopponent, Hissene Habre.

Moreover, interventionand a sustained foreignrole in defending a gov-

ernmentagainst its internalopposition may discreditthatgovernmentin the

eyes of the broader populace, which comes to see the regimeas an instrument

of a foreignpower and as betrayingthe nation which it purportsto serve.21

In other words, it may undermine furtherthe legitimacyupon which the

19. On the permanence of militarysolutions in the Horn, for example, see Nolutshungu,

"AfricanInterests,"p. 411.

20. Ogunbadejo, "Soviet Policies in Africa,"p. 125.

21. Rene Lemarchand, "The CIA in Africa:How Central? How Intelligent?"JournalofModern

AfricanStudies,Vol. 14, No. 3 (1976), p. 418, makes a similar point with referenceto regime

dependence on covertassistance.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa'sSecuritySystem1143

stabilityof a governmentultimatelyrests. In Angola, the Soviet and Cuban

presence has evoked a hostile nationalistreactionwithin the MPLA and in

the population at large.22In Chad, Goukouni's recourse to massive Libyan

support in late 1980 redounded to Habre's favor,as the formercame to be

seen by many Chadians as the puppet of a foreignoccupier with designs on

Chad's sovereignty.23

However, it is again not necessarily the case that interventionwill have

these effects.It may on the contraryset the stage forlonger termstabilityby

removing short-livedthreats to basically popular and legitimateregimes.

Britishinterventionin the face of army mutinies in east Africain the mid-

1960s may be cited in this context. One might also cite here the recent

Senegalese interventionin Gambia.

Moreover, foreigninterventionand sustained militarypresence need not

discreditan incumbent government.There is littleevidence to support the

view, forexample, that the French presence in Senegal, the Ivory Coast, or

Gabon has rendered the governmentsof these countriesillegitimatein the

eyes of their publics. Whether interventionhas this impact depends on a

number of factors: the comportmentof foreignpersonnel, the degree to

which militaryinvolvementis accompanied by economic benefitsto the target

state,the performanceof the incumbentgovernmentin meetingthe economic

and social aspirations of the indigenous population, the effectivenessof the

opposition in mobilizingpublic opinion, and so on.

In short, it would appear that it is neither easy nor very productive to

generalize about interventionand its impact on securityin the senses men-

tioned above. Interventionin Africais not a homogeneous phenomenon. To

treat it as such impedes understanding of Africanaffairs.More generally,

the Africanexperiencecalls into question the undifferentiated condemnation

of forceprojectioninto ThirdWorld conflictcommon among westernliberals.

22. See AfricaConfidential,Vol. 23, No. 15 (1982), pp. 5-6, and Vol. 24, No. 2 (1983), pp. 7, 8,

for accounts of factionalconflictwithin the MPLA between pro-Sovietideologues and "prag-

matic" nationalists. Xan Smiley, "Inside Angola," The Nezv YorkReviewofBooks,February 17,

1983, p. 40, commentson popular resentmentof the Cubans in Angola. The rumor,afterNeto's

death, that the Russians had killed him is indicative of the widespread suspicion of Soviet

intentions(ibid., p. 42).

23. Habr6 repeatedlycalled attentionto Goukouni's connectionwith the Libyan "conquerors."

That Goukouni's relationshipwith the Libyans worked to his disadvantage is evident in the

defectionsof several leading officialsin his governmentafterthe announcementin January1981

of the mergerof the two countries. Keesing'sContemporanyArchives (1981), pp. 31161, 31162.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

International

Security1144

THE REGIONAL CONSEQUENCES OF INTERVENTION

That said, it is possible to accept a numberof more carefulconclusions about

the relationshipbetween interventionand regional security.First,there ap-

pears to be a clear connection between interventionand increased defense

spending and weapons procurementin contiguous states. The South African

defense budget, forinstance, doubled and then doubled again in the after-

math of the Angolan affair,going from335 millionrand in 1972-1973to 1,564

million rand in 1979-1980. While some of this may be accounted for by

inflationin militarycosts, this corresponded to a rise in the defense share of

GNP from2.1 percent to 4.5 percent and in the defense share of central

governmentexpenditure from 11.8 percent to 16.8 percent.24It would be

inaccurate to ascribe this substantial real increase in defense expenditure

solely to Soviet-Cuban militaryactivities in Angola. The collapse of the

Portuguese empire in southern Africa and the increasing pressure on the

Smith regime in Rhodesia would have altered the basis of the republic's

securitywhetheror not externalforceshad intervened.Moreover,the specter

of growinginternalunrestfavoredexpansion in the republic's defense estab-

lishment. But it is true nonetheless that these processes were particularly

disturbingfromthe white South Africanperspective,given the close involve-

mentin themof communistpowers fromoutside the region.As Robin Hallett

has observed, the South Africanpreoccupation with and fear of the "com-

munist menace" should not be belittled,but taken at face value.25

The Kenyan response to the growingconflictin the Horn was to increase

defense expenditure from $113 million in 1977 to $255 million in 1979.26

Again, this should perhaps not be ascribed principallyto Soviet and Cuban

involvement,given the long historyofproblemsin relationsbetween Somalia

and Kenya. But as a regionalpower committedto capitalistdevelopmentand

to close ties with the West, Kenya could not have been indifferentto the

rapid growth in the regional presence of the Soviet Union and Cuba.27

Moreover, the factthat this shiftin Kenyan policy was a response primarily

to a "Somali threat" does nothing to diminish the causal connection to

24. SouthAfricanYearbook(1981), p. 286.

25. Robin Hallett, "South AfricanInterventionin Angola, 1975-1976," AfricanAffairs,Vol. 77,

No. 308 (1978), p. 363. In this context,Coker has argued that the failureof the United States to

prevent Soviet interventionin southern Africapushed South Africainto developing itselfinto

an independent militarypower. Coker, "South Africa,"p. 59.

26. ACDA, WorldMilitaryExpenditures, 1970-1979, p. 64. Figures are in 1978 constantdollars.

27. For the perceived link between Kenyan securityand the activityof communistpowers in

the Horn, see WeeklyReview(Nairobi), February27, 1978, pp. 8-9, 11.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa'sSecuritySystem| 145

intervention,forit was a Somali militaryintrusioninto Ethiopia in support

of insurgentsin the Ogaden which occasioned the Ogaden War and which

provided the Kenyans with graphic evidence of continuingSomali irreden-

tism.

Finally, in a directresponse to Libyan interventionin Chad and to what

the Nigerians believed to be Libyan involvement in sectarian violence in

Kano in late 1980, Nigeria adopted a five-yeardefense procurementplan

valued at $6.4 billion and increased its projected defense budget for 1981-

1982 by 35 percent.28This reversed the post-civilwar downward trend in

Nigerian defense spending and in the size of the country'sdefense estab-

lishment.29

In this sense, interventionis a major contributorto what is a region-wide

growthtrendin size of forces,militaryexpenditure,and arms procurement.

In 1968, Africa accounted for only 7 percent of developing country arms

imports. In 1978, the correspondingfigurewas 32 percent.30This occurred

despite a substantial drop in the dollar value of the purchases of Egypt-

which was in the late 1960s and early 1970s the continent's largest arms

importer-afterthe October War. Africanpurchases were somewhat lower

(around 26 percent of developing countryarms imports) in 1979. This re-

flectedprimarilythe curtailmentin Ethiopian demand forarms31ratherthan

any significantimprovementin the securitysituationofthe regionas a whole.

It remained the case that imports were approximately3.5 times higher in

constant dollars at the end of the period than at the beginning and that

regional defense spending had virtuallydoubled (going from$5,553 million

28. Cf. JuanDe Onis, International HeraldTribune,January16, 1981. De Onis ascribes thisincrease

to worries over Libyan activityin Chad and quotes President Shagari as saying that "Nigeria

was -beingforcedby world events to reassess its securityand defense expenditure." In view of

substantialshortfallsin oil revenues and cutbacksin governmentexpendituresacross the board,

it is unclear whether these targetshave been or will be met. On Nigerian defense spending,

see also Karen Thapar, London Times,April 14, 1981.

29. On the downward trendin Nigerian defense expenditureand manpower in the mid-1970s,

see Edward Kolodziej and RobertHarkavy, "Introduction,"pp. 2, 7, and JohnOstheimer and

Gary Buckley, "Nigeria," in Kolodziej and Harkavy, SecurityPolicies of DevelopingCountries

(Lexington,Mass.: D.C. Heath, 1982).

30. ACDA, WorldMilitanyExpenditures,1963-1973 (Washington: ACDA, 1975), Table 4; and

WorldMilitaryExpenditures, 1970-1979, Table 2. If one omits Egypt, whose primarysecurity

preoccupation was the Middle East and not Africa,the figurefor 1968 would have been 3.5

percent.

31. Ethiopian importsfellfrom$1.1 billion in 1978 to $192 millionin 1979 (both figuresin 1978

constantdollars). This drop largelyaccounts forthe decrease in regional spending from1978 to

1979 ($1.2 billion).

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Security1146

International

in 1970 to $9,090 millionin 1979), while therewere approximately2.5 times

as many indigenous militarypersonnel in the region in 1979 as in 1970, this

again despite declines in the size of the Nigerian and Egyptianarmed forces.

This shiftin resource allocation is a response to a continental climate of

growing violence-internal and external-of which interventionis a promi-

nent part. While it is perhaps simplisticto maintainwithoutqualificationthat

arms races lead to war, it is nonetheless true thatthe betterarmed a state is,

the more able it is to contemplatethe use of force.The increasingavailabilitv

in the region of the instrumentsof violence removes what was an important

constrainton inter-Africanconflict.Moreover, the growing prominence of

militaryexpenditure in national budgets and of militarytasks in national

policy diverts scarce resources, human, financial, and material, from the

pursuit of other objectives such as health, development, and social welfare

in societies which are already forthe most part desperatelypoor.

Second, the increasingincidence of interventionin the late 1970s and early

1980s in Africareflectsan erosion of the normativebasis of interstaterelations

in the region. For most of the 1960s and the firstyears of the 1970s, Africa

was distinguished for having a structureof norms which limited intra-re-

gional conflict,inhibitedintrusionby externalactors, and conduced to mul-

tilateralconflictresolution.Among the most importantof these norms were:

1. non-interference in the internalaffairsof Africanstates;

2. non-recourseto forcein inter-African relations;

3. non-recourse to extra-regionalmilitaryassistance in the resolution of

regional disputes (i.e., Africansolutions to Africanproblems);

4. respectforthe territorial statusquo establishedby the colonial powers.32

The recentfrequencyof interventionin the region suggests in the firstplace

that regional actors are increasinglywilling to seek militaryassistance from

external actors. Moreover, the great majorityof instances of intervention

since the mid-1970s (14 of the 16 cases since 1974 listed in Table I) have

involved African actions against fellow Africans. This indicates a greater

proclivityon the part of regionalactorsto involve themselvesin civilconflicts

in otherstates (e.g., Libya in Chad, Tunisia, and Uganda; Somalia in Ethiopia

and vice versa; Zaire in Chad; and Senegal in Gambia), to use forcein their

relationswith fellowOAU members(e.g., Libya and Chad, Libya and Sudan,

32. On these points, see Zartman, "Africaas a Subordinate State System," pp. 559-561.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa'sSecuritySystem| 147

Somalia and Ethiopia, Zaire and Angola, Tanzania and Uganda), and to

challenge the territorialstatus quo (once again Libya vis-a-vis Chad, Zaire

vis-a-vis Cabinda, Somalia vis-a-vis the Ogaden, and Morocco vis-a-vis the

WesternSahara). Many of the disputes and claims cited here are by no means

new. The point is that fora substantialperiod of time they were muted or

diverted into other channels by the existence of a widely accepted body of

principlesgoverningthe conduct of regional actors. The evidence cited here

suggests that the impact of these principles on the behavior of states is

weakening.

The increasingnumbers of interventionsin this period not only reflectbut

fosterthis erosion of previously accepted norms, for, in the absence of a

supranationalauthoritycapable of enforcingrules, compliance is based upon

mutual interest and upon the expectation that others will comply. Each

violation of these norms challenges this expectation. As the latterbecomes

increasinglyuntenable, regional actors will move furthertowards seeking

other means of guaranteeingtheirsecurityand pursuing theirinterests.

For these reasons, it is legitimateto question whether the conventional

characterizationsof inter-African relationsin termsof principlessuch as the

non-use of force,non-interference in internalaffairs,general acceptance of

the territoriallegacy of imperialism,the commitmentto Pan-Africanism,and

multilateralconflictresolution are still valid, and, if they remain so, how

long this will last. It is not coincidentalthat this period has witnessed suc-

cessive crises in the OAU and the immobilityof thatorganizationwithregard

to basic national and regional securityissues. Too many of its memberstates

no longer take seriously the organization's constitutiveprinciples in situa-

tions where the latter impinge upon the pursuit of fundamental national

objectives. It is as an element of this growing regional disorder that the

impact of interventionon Africaneconomic development should be seen.

Regional unpredictabilityand disarraymake the continentas improbable an

economic investmentforprivate interestsboth withinAfricaand outside it

as it is an unpromisingpoliticalinvestmentforexternalactorsseeking lasting

influenceand strategicgain.33

Lastly, while it was argued in a previous section that generalizationwith

respectto interventionand the intensityand durationof militaryconflictwas

33. On this point, see Xan Smiley, "Misunderstanding Africa," AtlanticMonthly,September

1982, p. 79.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Security| 148

International

questionable, it appears that the involvementof the superpowers or of pow-

ers perceived to be acting in concertwith them complicates the attemptto

resolve the political questions underlyinghostilitiesby stimulatingthe inter-

est of and counteractionby rival actors. This adds an additional dynamic of

conflictto regional crises and renders them even more intractablethan they

might otherwise be. Angola is a clear case of this. When Zairean troops

armed and trainedby the Americansand Chinese enteredAngola in February

1975, this evoked a mild Cuban and Soviet response (arms deliveriesand the

arrivalof small numbersofCuban advisers). Competitiveescalation involving

both superpowers and their allies within and beyond the region ensued.

While Soviet-Cuban assistance was sufficientto guarantee the MPLA's mil-

itaryvictory,a durable solution to the Angolan problem,difficultas it would

be to achieve even withoutthe global dimension, is furtherimpeded by the

residue of East-West competition.The U.S. continues to refuseto recognize

the Luanda regime and supports, verbally if not materially,the UNITA

challenge to the MLPA. The legacy of East-West competitionin Angola has

effectsbeyond that country'sborders as well, with the U.S. seeking to link

a settlementof the Namibian question to the withdrawal of Cuban forces

fromAngola.

In the Horn, this effectwas and is less evident, though the United States

persistsin its refusalto normalize relationswith Ethiopia, while close Amer-

ican allies in the region (Somalia, Egypt, Sudan, and Saudi Arabia) finance,

arm, and give sanctuary to secessionist movements contesting Ethiopia's

controlof Eritrea,Tigre, and the Ogaden.

In the case of Chad, the perceived close connectionbetween Libya and the

Soviet Union was instrumentalin inducing the United States, in conjunction

with Sudan and Egypt, to arm and financeHissene Habre's challenge to the

Libyan-backed Goukouni regime in 1980-1981. This support made possible

Habre's victoryin 1982 and contributedto the demise of OAU effortsto

obtain a political settlement.Now the shoe is presumablyon the other foot,

Habre&s close connections with the West being one factoramong several

motivatingLibya's renewed support for Goukouni and Soviet acquiescence

in this Libyan policy.

In brief,interventionby aligned regional powers or by outside forces on

one side or the other of the East-West competitiontends to embroil local

conflictsin global rivalries.This conflictswith the oft-statedAfricanobjective

thatthe continentshould not become a terrainon which extra-regionalactors

fighttheirbattles. Moreover, while recognizingthatprospects forresolution

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa'sSecuritySystem| 149

of many African disputes may be small in any case, there is evidence to

support the conclusion that the intrusionof global variables into regional

conflictsmakes conflictresolutioneven more difficult.

To summarize, growing numbers of interventionsin Africafosterthe mil-

itarizationof the continent,reflectand furtherthe corrosionof the normative

basis of regional security,and contributeto a climateof unpredictabilityand

riskwhich discourages development. Moreover, in a number of cases, inter-

ventionby actors with close ties to the Soviet Union or the United States has

blurred the distinctionbetween regional concerns and global rivalriesand,

as such, has complicated conflictresolution.In these senses, interventionis

not only a symptomof basic problems of regional security,but itselfcontrib-

utes to a furtherdeteriorationof securityin the region.

Conclusionand Prospect

For these reasons, it is clearly in the interestof the Africancommunityto

minimize the incidence of intervention,whetheror not in specificinstances

it may be consistentwith regional or national core values. In this context,

one may hope that the realizationthatthe fabricof Africansecurityis begin-

ning to fraywill stimulateeffortsto repairit throughthe revitalizationof the

OAU role in conflictresolution,in a renewal of memberstates' commitments

to the organization and its charter.There is some ground for optimism on

this score in the determinationwith which states in the region sought to

avoid the collapse of the OAU in 1982. Most regimesin the regionapparently

continue to perceive a shared interest-based on a general awareness of the

precariousness of state structuresand consequent fearof the implicationsof

a serious breakdown in regional order-in the norms upon which the orga-

nization is based.

However, a revitalizationof the regional organization would have little

impact on the basic problems outlined in the firstsection of this paper. At a

sufficientlevel of intensityin a sufficientnumber of countries,these trends

of political fragmentationand economic decay could cause not only the

internalbreakdown of the states affected,but also a collapse of the African

interstatesystem. Ultimately,nothing short of a redraftingof the territorial

map will effectivelyaddress the problem of politicalfragmentation.Yet any

large scale movement in this directionwould in all likelihood create a level

of disorderin the regionwhich is betteravoided. Improvementin the regional

economic situation may mitigate some of these disintegrativepressures.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Security| 150

International

Leaving aside utopian solutions along the lines of the program for a new

internationalorder or the Brandt Commission report,it would appear that

only sustained and strongrecoveryin the industrialeconomies which con-

sume primaryexports will significantly improve the regional economic pic-

ture. Large scale write-offsof Africandebts would also be a constructive

contribution.

With regard to power projection by extra-regionalactors, to the extent

thattheyshare an interestin regional securityin Africa,caution is advisable

in consideringthe option of intervention.Potentialbenefitsto both the target

state and to the intervenermust be weighed against the impact of this kind

of activityon regional security.Tacit or explicitagreement among non-re-

gional actorson mutual restraintin theirresponse to local conflictis desirable,

not only in the usually mentioned sense that Third World confrontation

between East and West carrieswith it the danger of escalation and may do

considerable damage to relations between the two blocs, but also from a

regional securityperspective. Given that the United States continues to face

severe domestic constraintson force projection and policymakers in the

currentAdministrationapparentlydo not perceive vital American interests

to be at stake in Africancrises, while the Soviet Union has gained little.and

at considerable expense fromits involvementin Africanconflict,prospects

for restraintby the superpowers may be brighterthan at firstglance they

mightappear.34

Concerning interventionby local actors, restraintis all the more desirable

since it is upon compliance by OAU members that the strengthof the com-

munity'snormsconcerningthe use offorceand interference in internalaffairs

is based.

However, in attemptingto put forwardpolicy prescriptionsdesigned to

cope with the increasing use of forcein the region, one should not depart

too farfromregionalrealities.The currentstate of regionalpoliticsgives little

ground for enthusiasm. Economic decay, political fragmentation,growing

disparitiesin militarypower, the acceleratingimportof arms, an increasing

recourse to forcein regional disputes, the erosion of regional norms govern-

ing interstaterelations, the manifestincapacity of the OAU as presently

34. For a wider discussion of these points, see S. Neil MacFarlane, Interventionand Regional

Security,Adelphi Paper (London: InternationalInstituteforStrategicStudies, forthcoming);and

S. Neil MacFarlane, "Soviet Interventionin Third World Conflict,"PSIS Occasional Paper #2

(Geneva: ProgrammeforStrategicand InternationalStudies, 1983), pp. 35-43.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Africa'sSecuritySystem1151

constitutedto deal with internaland regional conflicts,and its near demise

over the Western Sahara and Chad questions all justifypessimism. The

prospect for the region is one of increasingfrustration,disintegration,and

civil and interstateconflict.Perhaps the most that can be hoped for is the

eventual coalescence of a new concertof power out of this morass, with the

strongcollectivelyassuming responsibilityforregional security,or, alterna-

tively,the emergence of a definiteand recognized balance of power discour-

aging revisionistchallenges to regional order.

This content downloaded from 62.122.79.69 on Fri, 13 Jun 2014 21:46:05 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Kkdat Presentation Feb. 18, 2019 LatestDocument22 pagesKkdat Presentation Feb. 18, 2019 LatestJane Dizon81% (16)

- SWOT AnalysisDocument12 pagesSWOT AnalysisAsaph Wutawunashe0% (1)

- Mount Athos and The European CommunityDocument86 pagesMount Athos and The European CommunityΜοσχάμπαρ ΓεώργιοςNo ratings yet

- s5 History African Nationalism 2020Document146 pagess5 History African Nationalism 2020James Guetta100% (1)

- Enuga S. Reddy United Nations and The Struggle For Liberation in South AfricaDocument125 pagesEnuga S. Reddy United Nations and The Struggle For Liberation in South AfricaDeclan Max BrohanNo ratings yet

- The First World War NotesDocument20 pagesThe First World War Notesckjoshua819100% (8)

- Fixing Africa MayDocument75 pagesFixing Africa MayNati ManNo ratings yet

- Dos ChinasDocument13 pagesDos ChinasMarco ReyesNo ratings yet

- The African UnionDocument8 pagesThe African UnionMuhammad wali JanNo ratings yet

- South West African PoliceDocument1 pageSouth West African PoliceХристинаГулеваNo ratings yet

- Lecture NotesDocument3 pagesLecture NotesAttila FeketeNo ratings yet

- 9525-Assembly en 18 22 July 1978 Assembly Heads State Government Fifteenth Ordinary SessionDocument17 pages9525-Assembly en 18 22 July 1978 Assembly Heads State Government Fifteenth Ordinary SessionMarco Antonio ActiumNo ratings yet

- LibyanDocument3 pagesLibyanRusith FernandoNo ratings yet

- NIGERIADocument3 pagesNIGERIAJon LishmanNo ratings yet

- 774 History 1975 - 1986 Website ReadyDocument104 pages774 History 1975 - 1986 Website ReadyLuis FerreiraNo ratings yet

- 39221-Doc-175. The Post-Amnesty Programme in The Niger Delta. Challenges and ProspectsDocument9 pages39221-Doc-175. The Post-Amnesty Programme in The Niger Delta. Challenges and ProspectsAdedayo MichaelNo ratings yet

- 2 52 1634019042 5IJPSLIRDEC20215.pdf1111Document12 pages2 52 1634019042 5IJPSLIRDEC20215.pdf1111TJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Polycop L3 Lea 2023Document17 pagesPolycop L3 Lea 2023AissatouNo ratings yet

- p.7 Ple Unique Set - Sst-1Document40 pagesp.7 Ple Unique Set - Sst-1Amazing KingsNo ratings yet

- Social Studies 1 8-9 NotesDocument98 pagesSocial Studies 1 8-9 NotesmercymatopaNo ratings yet

- Franck Stealing Sahara 1976Document29 pagesFranck Stealing Sahara 1976Fausto GiudiceNo ratings yet

- The African Stakes of The Congo War by John F. ClarkDocument266 pagesThe African Stakes of The Congo War by John F. ClarkLeblanc BahigaNo ratings yet

- Terrorism: Proliferation of Weapons of Mass DestructionDocument3 pagesTerrorism: Proliferation of Weapons of Mass DestructionCharlene CapinpinNo ratings yet

- Nigerian Civil WarDocument31 pagesNigerian Civil WarOlayinka Awofodu100% (1)

- Tracking Zimbabwe's Political History: The Zimbabwe Defence Force From 1980-2005Document33 pagesTracking Zimbabwe's Political History: The Zimbabwe Defence Force From 1980-2005Petrus_OptimusNo ratings yet

- Namibias Foreign Relations MushelengaDocument20 pagesNamibias Foreign Relations MushelengaAmogh KothariNo ratings yet

- Africa in The Unipolar World-1Document10 pagesAfrica in The Unipolar World-1Hafsa Yusif100% (1)

- LBS - September 2023 PDFDocument87 pagesLBS - September 2023 PDFAdemuyiwa OlaniyiNo ratings yet

- Vol 5. En. Hashim Mbita Southern African Liberation StrugglesDocument596 pagesVol 5. En. Hashim Mbita Southern African Liberation StrugglesLucyNo ratings yet

- K.J.Somaiya Institute of Management Science and ResearchDocument17 pagesK.J.Somaiya Institute of Management Science and ResearchSachin Shetye100% (1)

- Apartheid NamibiaDocument43 pagesApartheid NamibiaAdrian BottomleyNo ratings yet

- Fifty Years of African UnityDocument1 pageFifty Years of African UnityCityPressNo ratings yet

- Subject Section Task Title WordingDocument6 pagesSubject Section Task Title WordingAmanda GyarmatiNo ratings yet

- Nam 1Document16 pagesNam 1ANURAG SINGHNo ratings yet

- Least Developed CountriesDocument1 pageLeast Developed CountriesAman TyagiNo ratings yet