Professional Documents

Culture Documents

13 Full

Uploaded by

Debora Duran San RomanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

13 Full

Uploaded by

Debora Duran San RomanCopyright:

Available Formats

ED ITORIAL

Language and the brain

L

anguages—exquisitely structured, complex, and the brain. People who were deprived of access to lan-

diverse—are a distinctively human gift, at the guage as children (e.g., deaf individuals without access

very heart of what it means to be human. As such, to speakers of sign languages) show patterns of neu-

language makes for both a particularly important ral connectivity that are radically different from those

and difficult topic in neuroscience. A dominant with early language exposure and are cognitively dif-

early approach to the study of language was to ferent from peers who had early language access. The

treat it as a separate module or organ within later in life that first exposure to language occurs, the

the brain. However, much modern empirical work has more pronounced and cemented the consequences. Lera Boroditsky

demonstrated that language is integrated with, and in Further, speakers of different languages develop dif-

is an associate

constant interplay with, an incredibly broad range of ferent cognitive skills and predispositions, as shaped

professor in the

neural processes. by the structures and patterns of their languages. Ex-

Department of

Downloaded from http://science.sciencemag.org/ on October 4, 2019

Unlike other areas of neuroscience investigation perience with languages in different modalities (e.g.,

(e.g., vision, motor action) that have relied heavily on spoken versus signed) also develops predictable dif- Cognitive Science

invasive techniques with animal models, the study of ferences in cognitive abilities outside the boundar- at the University

language lacks any such model. ies of language. For example, of California,

Furthermore, in language, the speakers of sign languages de- San Diego, CA, USA.

relationship between the form velop different visuospatial at- lera@ucsd.edu

of a signal and its meaning is

largely arbitrary. For example,

“…one cannot tention skills than those who

only use spoken language. Ex-

the sound of “blue” will likely

have no relationship to the prop-

understand the posure to written language also

restructures the brain, even

erties of light we experience as

blue nor to the visual written human brain without when acquired late in life. Even

seemingly surface properties,

form “blue,” will sound different

across languages, and have no understanding such as writing direction (left-

to-right or right-to-left), have

sound at all in signed languages.

No equivalent of “blue” will the contributions profound consequences for how

people attend to, imagine, and

even exist in many languages organize information.

that might make fewer or more of language…” The normal human brain that

or different color distinctions. is the subject of study in neuro-

With respect to language, the science is a “languaged” brain.

meaning of a signal cannot be It has come to be the way it is

predicted from the physical properties of the signal through a personal history of language use within an in-

available to the senses. Rather, the relationship is set dividual’s lifetime. It also actively and dynamically uses

by convention. linguistic resources (the categories, constructions, and

At the same time, language is a powerful engine of distinctions available in language) as it processes incom-

human intellect and creativity, allowing for endless re- ing information from across the senses.

combination of words to generate an infinite number Put simply, one cannot understand the human brain

of new structures and ideas out of “old” elements. Lan- without understanding the contributions of language,

guage plays a central role in the human brain, from how both in the moment of thinking and as a formative force

we process color to how we make moral judgments. It during earlier learning and experience. When we study

directs how we allocate visual attention, construe and language, we are getting a peek at the very essence of

remember events, categorize objects, encode smells and human nature. Languages—these deeply structured cul-

musical tones, stay oriented, reason about time, perform tural objects that we inherit from prior generations—

mental mathematics, make financial decisions, experi- work alongside our biological inheritance to make

ence and express emotions, and on and on. human brains what they are.

Indeed, a growing body of research is documenting

how experience with language radically restructures –Lera Boroditsky

CREDITS: (PHOTO) ASA MATHAT

10.1126/science.aaz6490

SCIENCE sciencemag.org 4 OCTOBER 2019 • VOL 366 ISSUE 6461 13

Published by AAAS

Language and the brain

Lera Boroditsky

Science 366 (6461), 13.

DOI: 10.1126/science.aaz6490

Downloaded from http://science.sciencemag.org/ on October 4, 2019

ARTICLE TOOLS http://science.sciencemag.org/content/366/6461/13

RELATED http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/366/6461/48.full

CONTENT

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/366/6461/50.full

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/366/6461/55.full

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/366/6461/58.full

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/366/6461/62.full

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/366/6461/33.full

http://science.sciencemag.org/content/sci/366/6461/83.full

PERMISSIONS http://www.sciencemag.org/help/reprints-and-permissions

Use of this article is subject to the Terms of Service

Science (print ISSN 0036-8075; online ISSN 1095-9203) is published by the American Association for the Advancement of

Science, 1200 New York Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20005. The title Science is a registered trademark of AAAS.

Copyright © 2019 The Authors, some rights reserved; exclusive licensee American Association for the Advancement of

Science. No claim to original U.S. Government Works

You might also like

- The Child and the World: How the Child Acquires Language; How Language Mirrors the WorldFrom EverandThe Child and the World: How the Child Acquires Language; How Language Mirrors the WorldNo ratings yet

- Properties of Human LanguageDocument3 pagesProperties of Human LanguageViviana Zambrano100% (1)

- The Creativity of Human Language: Competence. It SimplyDocument6 pagesThe Creativity of Human Language: Competence. It SimplyDesi NataliaNo ratings yet

- Hagoort - 2019 - The Neurobiology of Language Beyond Single-Word Processing - Revisión - SCIENCEDocument5 pagesHagoort - 2019 - The Neurobiology of Language Beyond Single-Word Processing - Revisión - SCIENCEEmmanuel Domínguez RosalesNo ratings yet

- A Compendium SampleDocument82 pagesA Compendium SampleSomaya M. AmpasoNo ratings yet

- Heuttig - Pickering - 2019 - Literacy Advantages Beyond ReadingDocument12 pagesHeuttig - Pickering - 2019 - Literacy Advantages Beyond ReadingMarcio SantosNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Human LanguageDocument6 pagesCharacteristics of Human LanguageWonston YapNo ratings yet

- How language styles impact negotiationsDocument5 pagesHow language styles impact negotiationsCristy Soledad PAEZ SARAZANo ratings yet

- Reading Optimally Builds On Spoken Language: Implications For Deaf ReadersDocument19 pagesReading Optimally Builds On Spoken Language: Implications For Deaf ReadersLuiz SantosNo ratings yet

- Language and Cognition: Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience December 2014Document4 pagesLanguage and Cognition: Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience December 2014rashmiNo ratings yet

- Journal Review ManangguangDocument6 pagesJournal Review Manangguangrian antoNo ratings yet

- Classwork 5 Properties of Human LanguageDocument3 pagesClasswork 5 Properties of Human LanguageViviana ZambranoNo ratings yet

- Fnhum 16 819956Document8 pagesFnhum 16 819956Furkan ERBEYNo ratings yet

- 2023-Dyslexia-Research-and-Evidence-Based-Practices-October-24-2023Document56 pages2023-Dyslexia-Research-and-Evidence-Based-Practices-October-24-2023ana.vioreanuNo ratings yet

- Marosan LangAsObjectOfStudy PDFDocument4 pagesMarosan LangAsObjectOfStudy PDFRizwana RahumanNo ratings yet

- Definitions of LanguageDocument56 pagesDefinitions of Language1bruceleeeNo ratings yet

- Human Language PropertiesDocument4 pagesHuman Language Propertieswendy nguNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Consequences of Bilingualism For Language Processing and CognitionDocument18 pagesUnderstanding The Consequences of Bilingualism For Language Processing and CognitionEmir ŠkrijeljNo ratings yet

- Language May Shape How We ThinkDocument29 pagesLanguage May Shape How We ThinkMARIO ROBERTO CORDOBA CANDIANo ratings yet

- What Do Language Disorders Reveal About Brain-Language Relationships? From Classic Models To Network ApproachesDocument14 pagesWhat Do Language Disorders Reveal About Brain-Language Relationships? From Classic Models To Network ApproachesvalentinepoulainNo ratings yet

- Grammatical Subjects in Home Sign Abstract LinguisDocument6 pagesGrammatical Subjects in Home Sign Abstract LinguisHudaibia SaeedNo ratings yet

- División TextoDocument17 pagesDivisión TextoAna EsparzaNo ratings yet

- Language, Society and Culture: ELT 121 Lady Lou C. Pido, MALTDocument23 pagesLanguage, Society and Culture: ELT 121 Lady Lou C. Pido, MALTKinderella PidoNo ratings yet

- Aspects of human language propertiesDocument4 pagesAspects of human language propertiesMohamed El Moatassim Billah100% (1)

- T02R01 (Cook - 2003 - 40-48103-104)Document7 pagesT02R01 (Cook - 2003 - 40-48103-104)Anna SzollosiNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 78.131.36.94 On Wed, 24 Nov 2021 12:31:14 UTCDocument6 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 78.131.36.94 On Wed, 24 Nov 2021 12:31:14 UTCBorostyánLéhnerNo ratings yet

- Slobin (2003)Document18 pagesSlobin (2003)Keith WheelerNo ratings yet

- Fedorenko 2016Document22 pagesFedorenko 2016Ali YassinNo ratings yet

- LanguageDocument55 pagesLanguagealfredNo ratings yet

- Language-Culture LinkDocument8 pagesLanguage-Culture LinkMelody Jane CastroNo ratings yet

- LANGUAGE 1 Group 3Document3 pagesLANGUAGE 1 Group 3janeypauig25No ratings yet

- BEDNY - 2017 - Evidence From Blindness For A Cognitively Pluripotent CortexDocument12 pagesBEDNY - 2017 - Evidence From Blindness For A Cognitively Pluripotent CortexcarolinaNo ratings yet

- Class 2 Properties of Language YULEDocument19 pagesClass 2 Properties of Language YULEHelena López100% (2)

- GED0115Sec 18groupno.2 OutlineDocument4 pagesGED0115Sec 18groupno.2 OutlineFuturamaramaNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Relativity PDFDocument13 pagesLinguistic Relativity PDFSoyoko U.No ratings yet

- 2016 SGM PsychonomicDocument6 pages2016 SGM PsychonomicsadalvaryNo ratings yet

- Tracking The Evolution of Language and SpeechDocument6 pagesTracking The Evolution of Language and SpeechirenemaneroNo ratings yet

- The Language Instinct by Steven Pinker SummaryDocument2 pagesThe Language Instinct by Steven Pinker SummaryTazeen Anwar100% (1)

- Part I, Lesson IDocument6 pagesPart I, Lesson IGomer Jay LegaspiNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Psycholinguistics: Language, Mind and BrainDocument24 pagesAn Introduction To Psycholinguistics: Language, Mind and BrainZeineb AyachiNo ratings yet

- Language: First LessonDocument4 pagesLanguage: First LessonCheska Blanza OcampoNo ratings yet

- El100 Aj ReviewerDocument5 pagesEl100 Aj ReviewerabgNo ratings yet

- Horowitz-Kraus 2015Document9 pagesHorowitz-Kraus 2015Siti Ramlah MalikNo ratings yet

- NativismDocument4 pagesNativismKeiros FuegoNo ratings yet

- Language skills activity comparison and resourcesDocument5 pagesLanguage skills activity comparison and resourcesTiffany LugoNo ratings yet

- Core Language of ThoughtDocument4 pagesCore Language of ThoughtVaso VukotićNo ratings yet

- Linguistics and language teachingDocument59 pagesLinguistics and language teachingCres Jules ArdoNo ratings yet

- PropertiesDocument6 pagesPropertiesRagil Rizki Tri AndikaNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Vocal Learning and Spoken Language - JARVIS 2019Document6 pagesEvolution of Vocal Learning and Spoken Language - JARVIS 2019Giovana Coghetto SganzerlaNo ratings yet

- Language and SpeechDocument9 pagesLanguage and SpeechMako KirvalidzeNo ratings yet

- Linguistics - Final SummaryDocument141 pagesLinguistics - Final SummaryjulibreNo ratings yet

- PCOMDocument9 pagesPCOMXhiana ParkNo ratings yet

- Linguistics IntroductionDocument64 pagesLinguistics IntroductionAngelou BatallaNo ratings yet

- ING218-The Study of MeaningDocument3 pagesING218-The Study of Meaningafandena256No ratings yet

- The Evolution of Human Communication and LanguageDocument16 pagesThe Evolution of Human Communication and LanguageAshwin Hemant LawanghareNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Linguistic and Idioms-AranjatDocument7 pagesCognitive Linguistic and Idioms-AranjatBranescu OanaNo ratings yet

- Reading (Process) PDFDocument11 pagesReading (Process) PDFsalamzulkifli88No ratings yet

- Classwork 5Document2 pagesClasswork 5Viviana ZambranoNo ratings yet

- Linguistic-Mokhtasara-Blida - PDF Version 1 PDFDocument33 pagesLinguistic-Mokhtasara-Blida - PDF Version 1 PDFjojoNo ratings yet

- The Nature of Language and CommunicationDocument4 pagesThe Nature of Language and CommunicationCool FireNo ratings yet

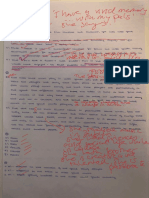

- 2bh Verbos ReescribirDocument1 page2bh Verbos ReescribirDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Pasiv CausatDocument2 pagesPasiv CausatDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Conditional SentencesDocument1 pageConditional SentencesDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Future TenseDocument1 pageFuture TenseQuel MenorcaNo ratings yet

- Documento 18Document1 pageDocumento 18Debora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Tests Answer KeyDocument22 pagesTests Answer KeyDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Photo 2022 05 19 11 36 42Document1 pagePhoto 2022 05 19 11 36 42Debora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- RW. ModalsDocument1 pageRW. ModalsDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Photo 2022 10 20 12 18 13Document1 pagePhoto 2022 10 20 12 18 13Debora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- IF ONLY WISHES AND CONDITIONALSDocument3 pagesIF ONLY WISHES AND CONDITIONALSDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- PresentaciónDocument10 pagesPresentaciónDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- RelativeDocument3 pagesRelativeDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Ioould: Part FromDocument1 pageIoould: Part FromDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- WritingDocument3 pagesWritingDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

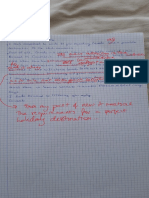

- Holiday: PointDocument1 pageHoliday: PointDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary: NameDocument3 pagesVocabulary: NameDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Grammar PastSimplePastContinuous1 18845Document2 pagesGrammar PastSimplePastContinuous1 18845Lourdes GLNo ratings yet

- Dublin XDocument3 pagesDublin XDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Unit Review Worksheet 2.1.7Document1 pageUnit Review Worksheet 2.1.7Debora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- ModalsDocument1 pageModalsDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Wordlist CatalanDocument12 pagesWordlist CatalanDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Reported Speech - Reporting VerbsDocument1 pageReported Speech - Reporting VerbsmirindaokasNo ratings yet

- Part 2 - Review: HintsDocument5 pagesPart 2 - Review: HintsjNo ratings yet

- Great Explorers 4Document39 pagesGreat Explorers 4ro5garcia-241918100% (1)

- FCE ArticleDocument4 pagesFCE ArticleMaria RuibalNo ratings yet

- Comparative and Superlative Grammar Guide PDFDocument2 pagesComparative and Superlative Grammar Guide PDFHeavy Beats OficialNo ratings yet

- FCE EssayDocument7 pagesFCE Essaynatalia100% (1)

- Winter Coloring Pages Owl Hat Happy HolidaysDocument1 pageWinter Coloring Pages Owl Hat Happy HolidaysDebora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- First Conditional 2Document2 pagesFirst Conditional 2Debora Duran San RomanNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behavior NotesDocument5 pagesOrganizational Behavior NotescyntaffNo ratings yet

- ITQOL Overview PDFDocument2 pagesITQOL Overview PDFSuriya SuriNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Family Structures and LegaciesDocument27 pagesChapter 12 Family Structures and LegaciesKria CaillesNo ratings yet

- Walkthrough Grade 10 NTOT NewDocument37 pagesWalkthrough Grade 10 NTOT NewMarlyn Cutab0% (1)

- Effect of Examination On Curriculum at Elementary Level in Punjab: A Mixed Methods StudyDocument16 pagesEffect of Examination On Curriculum at Elementary Level in Punjab: A Mixed Methods StudyLaser RomiosNo ratings yet

- Mpu 3022Document2 pagesMpu 3022leela deviNo ratings yet

- A Leader's Guide: Communicating With Teams, Stakeholders, and Communities During COVID-19Document9 pagesA Leader's Guide: Communicating With Teams, Stakeholders, and Communities During COVID-19GuyMcgowanNo ratings yet

- Research Methods Psychology Course SyllabusDocument7 pagesResearch Methods Psychology Course SyllabuszzmasterNo ratings yet

- The Dispenser of Holy WaterDocument4 pagesThe Dispenser of Holy Watervarmaj818No ratings yet

- UNPACKING THE SELF-physical SelfDocument14 pagesUNPACKING THE SELF-physical SelfMaria Ligaya SocoNo ratings yet

- LEAD- Mobilizing People Through LeadershipDocument17 pagesLEAD- Mobilizing People Through LeadershipTap RamosNo ratings yet

- El Currículum Integral: Elizabeth Vidal Vergara Educadora de Párvulo, Especialista en Informática EducativaDocument19 pagesEl Currículum Integral: Elizabeth Vidal Vergara Educadora de Párvulo, Especialista en Informática EducativaDaniela Elizabeth Leviante MansillaNo ratings yet

- Group 6 Chapter 1 5Document51 pagesGroup 6 Chapter 1 5Katherine AliceNo ratings yet

- Smart Goal DC Template 2017Document2 pagesSmart Goal DC Template 2017api-388332973No ratings yet

- HM17 Anthony Jacquin Manual LRGDocument156 pagesHM17 Anthony Jacquin Manual LRGRudolfSianto100% (5)

- Little EmperorsDocument8 pagesLittle EmperorsSi Xuan LooNo ratings yet

- School Management and Educational LeadershipDocument8 pagesSchool Management and Educational LeadershipPaola GarcíaNo ratings yet

- What Is The Difference Between Intensive and Extensive ReadingDocument11 pagesWhat Is The Difference Between Intensive and Extensive ReadingWan Amir Iskandar Ismadi100% (2)

- How Important Communication in My Everyday ExistenceDocument1 pageHow Important Communication in My Everyday Existenceryz sorianoNo ratings yet

- BCBA BCaBA Task List 5th Ed PDFDocument5 pagesBCBA BCaBA Task List 5th Ed PDFMaria PascuNo ratings yet

- ChecklistDocument2 pagesChecklistSmruti rekha SahooNo ratings yet

- The Appreciative Heart: The Psychophysiology of Positive Emotions and Optimal FunctioningDocument23 pagesThe Appreciative Heart: The Psychophysiology of Positive Emotions and Optimal FunctioningProfessor João GabrielNo ratings yet

- Aims and Objectives of Peace EducationDocument13 pagesAims and Objectives of Peace EducationParag Shrivastava100% (1)

- GUIDANCE AND COUNSELLING Unit 1Document20 pagesGUIDANCE AND COUNSELLING Unit 1Mukul Saikia100% (10)

- Teenage Pregnancy - Research PaperDocument7 pagesTeenage Pregnancy - Research Paperapi-342069061No ratings yet

- Never Mind The Gap Neurophenomenology Ra-2Document30 pagesNever Mind The Gap Neurophenomenology Ra-2joNo ratings yet

- 1 Getting The Message AcrossDocument8 pages1 Getting The Message AcrossMadalin AndreiNo ratings yet

- William GlasserDocument3 pagesWilliam GlasserMyrelleNo ratings yet

- SafradDocument5 pagesSafradAzhar AhmedNo ratings yet

- Global Citizenship EssayDocument1 pageGlobal Citizenship Essayapi-601540070No ratings yet