Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Revolution Will Be Led by A 12-Year-Old Girl - Girl Power and Global Biopolitics

Uploaded by

lisaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Revolution Will Be Led by A 12-Year-Old Girl - Girl Power and Global Biopolitics

Uploaded by

lisaCopyright:

Available Formats

'the revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl': girl power and global biopolitics

Author(s): Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill

Source: Feminist Review , 2013, No. 105 (2013), pp. 83-102

Published by: Sage Publications, Ltd.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24571900

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sage Publications, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Feminist Review

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

105 lthe revolution will be led

by a 12-year-old girl1:1 1 Nike Foundation

(n.d.) 'The Girl Effect

website: The

girl power and global revolution poster',

http://www

.girleffect.org/

biopolitics

downloads/posters/

The_Revolution_

Poster.pdf, last

accessed

1 September 2011.

Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill

abstract

This paper presents a poststructuralist, postcolonial and feminist interrogation of the

'Girl Effect'. First coined by Nike inc, the 'Girl Effect' has become a key development

discourse taken up by a wide range of governmental organisations, charities and non

governmental organisations (NGOs). At its heart is the idea that 'girl power' is the best

way to lift the developing world out of poverty. As well as a policy discourse, the Girl

Effect entails an address to Western girls. Through a range of online and offline publicity

campaigns, Western girls are invited to take up the cause of girls in the developing world

and to lend their support through their use of social media, through fundraising and

consumption. Drawing on a wide range of policy documents, media outputs and offline

events, this paper explores the way in which the Girl Effect discourse articulates notions

of girlhood, empowerment, development and the Global North/South divide.

keywords

girl power; development; policy; empowerment; girlhood; virais

feminist review 105 2013

(83-102) © 2013 Feminist Review. 0141-7789/13 www.feminist-review.com

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

introduction: the girl effect

In 2009, in the midst of the Global Financial Crisis, the World Economic Forum

held its first ever plenary session on adolescent girls. An alliance of multi

national corporations, charity and non-governmental organisation (NGO) leaders

and government representatives put forward a bold claim: that girls hold the key to

ending world poverty and transforming health and life expectancy in the developing

world. Investment in girls, they argued, would unleash financial growth that would

put an end to the intergenerational cycle of poverty said to be crippling developing

nations. Girls who were healthy and well educated would marry later and have fewer

children. This in turn would improve their economic prospects and lead to better

health among their children. Family health and life expectancy would improve, and

with it the economic situation of developing nations would be transformed. This

sequence of transformations was termed 'the Girl Effect'. 2 World Economic Forum

(2009) 'World Economic

Forum Annual Meeting

The notion of the Girl Effect is fast becoming a prominent feature of global deve

2009: shaping the post

lopment discourse and practice, representing a shift in which key organisations

crisis world', http://

www.members

(including the United Nations (UN) and the World Health Organisation (WHO)). weforum.org/pdf/

change

AnnualReport/2009/

their investment strategies in order to target girls in developing countries. However,

sociaLbacklash

.htm, last accessed

the significance of the Girl Effect does not end here. It also entails an intensification

30 August 2011.

of the neo-liberalisation of development fused with neo-imperialist notions of

'saving' oppressed Southern women (Abu-Lughod, 2002), leading to a 'féminisation

of responsibility' (Chant, 2006). Moreover, it represents a new and distinctive form of

address to girls in the Global North and West. Via an extensive range of social media

campaigns, 'roadshows' and merchandising promotions, girls in affluent societies,

particularly the US, are hailed variously as the allies and saviours of their Southern

'sisters', using discourses of girl power and popular feminism. The Girl Effect, then, is

not a singular entity, but an assemblage of transnational policy discourses, novel

corporate investment priorities, biopolitical interventions, branding and marketing

campaigns, charitable events designed to produce a social movement for change,

and designer goods that invite young women in the North/West to express pride in

'being a girl'—an act that Girl Effect marketing suggests will contribute to efforts to

improve the lives of girls in other parts of the world.

Our aim in this paper is to sketch out the contours of the Girl Effect and explore its

key features. We understand the Girl Effect to be a discursive construction that

materialises across a range of sites, and perform a 'double reading' of the multiple

forms of address it entails to and about girls in the North and South. To do this, the

paper will move dynamically back and forth between the language of development

policies targeted at the Global South and discourses of the Girl Effect that are

3 The notions of the

designed to interpellate young women in the North/West.3

North or West are of

course highly problematic

We do not seek to evaluate the Girl Effect as a development strategy within a because of

—not least

the growing range and

framework concerned with the measurement of economic 'outcomes', norforce

do of

wediscourses of girl

84 feminist review 205 2013 'the revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl'

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

power in Asia and Latin offer a contribution to the important body of feminist research that evaluates the

America. As with other

designations, for example impact of interventions on women's lives (Johnson, 2009; Bee, 2011; Maclean,

'developing' versus 2012). While these evaluations are important, they do not exhaustively address

'developed' and First/Third

World, the notions of feminist concerns, or indeed fully scrutinise the power dynamics at play. In this

Global South and North

serve only to attempt to

paper we choose to focus on what we believe to be a crucial part of any critical

speak of a world feminist interrogation: a consideration of the political ramifications of the dis

characterised by massive

geographically patterned courses and practices being mobilised. Our theoretical approach can be described as

injustice and inequality,

feminist, poststructural ist and postcolonial—an approach that recognises that

while failing to capture

complexity and specificity. global inequalities that are gendered and racialised remain entrenched. We are

informed by the critique articulated by Marxist and postcolonial scholars who argue

that development policies, dominated by neo-liberal ideologies, frequently reinforce

rather than mitigate economic inequalities (Roy, 2002; Escobar, 2010). In addition,

we recognise the persistence of 'ways of seeing' the 'Third World woman' whose

origins are found in colonial times. Continued inequalities mean that much of the

critique raised by postcolonial feminism of those who claim to speak for 'third world

women' remains pertinent. The homogonisation of third world women, paternalistic

attitudes and notions of Southern women as oppressed by an essentialised 'culture'

continue to haunt development and humanitarian work (Narayan, 1995; Mohanty,

2003; Dogra, 2011; Wilson, 2011).

The current political moment, we argue, makes the need to critically consider the

Girl Effect discourse particularly evident. The Girl Effect's continued ascent into

public and policy prominence occurs against the backdrop of a global crisis of neo

liberalism that threatens to call into question the role of international institutions

such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank and the

economic policies they espouse (Chorev and Babb, 2009). In addition, the Girl

Effect emerged post-9/11, following the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Its

continued prominence is maintained as Western forces discuss their impending

withdrawal from Afghanistan (Traynor, 2012) and amid fears that any gains for

girls and women will be undone by the Taliban. The social transformations occurring

in the Middle East following the events of the 'Arab Spring' have also highlighted

the complex dynamics linking gender, religion and the relationship between the

Global North and South. Thus, the global shifts currently under way strongly

suggest that the discourse of the Girl Effect will become a focal point in the

relationship between the Global North and South in the years ahead.

The paper is organised around four themes and divided into corresponding sections.

First, we will examine the 'turn to girls' in policy and popular discourses,

highlighting the Girl Effect's contrasting constructions of girls in the Global North

or South as, respectively, empowered, postfeminist subjects and downtrodden

victims of patriarchal values. Second, we will discuss the depiction of girls in

developing countries as entrepreneurial 'subjects in waiting', in which extreme

poverty is regarded as having the potential to stimulate entrepreneurial capacities. If

this is how girls 'mean business' in the Global South, it will be juxtaposed with

Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill feminist review 205 2013 85

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

discussion of the iconic role played by successful global female entrepreneurs

involved in sponsoring the Girl Effect, whose stories are repeatedly mobilised in

promoting the initiative. In the third section of the paper, entitled 'i matter, and so

does she' we discuss the Girl Effect's address to North American young women and its

very particular form of 'commodity feminism' (Goldman, 1992). The feminist forms of

identification promoted will be examined, looking at how they erase difference and

power and questioning whether the Girl Effect is about global sisterhood and/or

cultural imperialism. The fourth section of the paper examines the Girl Effect as a

biopolitical strategy that makes an explicit link between 'empowerment', fertility

and the economic well-being of individuals and nations. It documents the way in

which a Northern-centric policy concern with 'teenage motherhood' is imposed

upon developing countries in a manner that occludes discussion of very different

situations and contexts. Finally, the conclusion pulls together the threads of the

argument, bringing a postcolonial feminist analysis to bear upon the Girl Effect

as a discursive object. We discuss its selective uptake of feminism and how it

yokes discourses of girl power, individualism, entrepreneurial subjectivity and

consumerism together with rhetorics of 'revolution' in a way that—perhaps

paradoxically—renders invisible the inequalities, uneven power relations and

structural features of neo-liberal capitalism that produce the very global injustices

that the Girl Effect purports to challenge.

the turn to girls and the 'girl-powering' of

development

The notion of the 'Girl Effect' was coined by the Nike Foundation in the mid-2000s,

and it is hard to exaggerate the impact it has had on development discourse and

policy. Within a few years, the majority of the key global players in the field

of health and development have signed up to this agenda. In 2007 the United

Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Development Fund for Women

(UNIFEM) and WHO established the UN Interagency Task Force on adolescent girls.4

4 UNESCO (2011) 'Gender

equality theme,

In 2008 the World Bank founded its Adolescent Girls Initiative, aimed atadolescent

improvinggirls webpage',

h ttp ://un esco.org/new/

girls and young women's economic opportunities. By 2009 girls' role in develop

en/unesco/themes/

ment was being discussed at Davos, and in 2010 the UK's Department for

gen der-equali ty/the mes/

adolescent-girls, last

International Development (DfID) launched 'Girl Hub', a collaboration with the

accessed 5 August 2013.

Nike Foundation whose declared aim is to scale up the implementation5 World

of the Girl

Bank (2008)

'Adolescent

Effect policy (independent Commission for Aid Impact, 2012).6 In October 2012, girl

theinitiative

launch', Press release,

first UN-designated International Day of the Girl Child was marked amid extensive

http://www. web

. worldbank. org/WBSITE/

public endorsement by NGOs and governmental bodies. This process EXTERNAL/NEWS/O,

constitutes a

'girl-powering' of development, the latest in a succession of 'waves'content

of develop

MDK-.21935449

ment policy that have included Women in Development (WID), pagePK:34370~

Women and

piPK:34424~

Development (WAD) and Gender and Development (GAD). This 'girl-powering',

theSitePK:4607,00

however, does not replace policy preoccupation with gender, but instead represents

86 fe minist review 10S 2013 'the revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl'

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

.html, last accessed 30 a prominent theme within it. To a certain extent the current focus on girls is

August 2011.

linked to long-standing concerns about the human rights of the girl child

6 Girl Hub, the

collaboration between (Burman, 1995; Bunting, 2005; Switzer, 2010). Attention to adolescent girls has

DfID and Nike, has been

also been increasing within the work of the United Nations since the late 1990s7

one in which DfID provided

the majority of financial (Croll, 2006). Nevertheless, it is only in recent years that these earlier themes have

contribution (£12.8 million

while Nike contributed come to constitute a broader policy 'turn' and to achieve a high level of public

£2.8). This fact as well as prominence.

inadequate regulatory and

implementation processes

came under criticism in a One of the things that makes the Girl Effect different from previous initiatives is its

report by the Independent

Commission for Aid explicit borrowing and mobilisation of discourses of 'girl power' that have been

Impact circulating in the West (and now increasingly elsewhere) over the last two decades.

7 UNICEF, WHO and

As has been well documented by gender and youth scholars, in the late twentieth

UNFPA (2003)

'Adolescents: profiles in and early twenty-first centuries, girls have become increasingly visible in con

empowerment', http://

www.unicef.org/

temporary popular culture and in governmental literature. Girls are depicted as

adolescence/files/ educationally successful, economically independent, and in control of their sexu

adolescent_profiles_eng

.pdf, last accessed ality and their reproductive capacities (Walkerdine, Lucey and Melody, 2001;

30 August 2011.

Dricoll, 2002; Aapola, Gonick and Harris, 2005; McRobbie, 2007; Ringrose, 2007).

Notions of choice, agency, independence and empowerment have gained promi

nence in discussions of girlhood, and this is sometimes contrasted with construc

tions of young men, particularly in those media discourses that paint masculinity

as 'in crisis', young women have become 'luminous' (McRobbie, 2009), they are

depicted as 'can do girls' (Harris, 2004), and middle-class girls in particular are

often presented as the ideal subjects of neo-liberalism: hardworking, entrepre

neurial authors of their own 'choice biographies'.

However, alongside this depiction of girls as empowered and successful, another

significant construction has been the representation of girls as vulnerable. Harris

(2004) analyses the way in which discussions of girlhood are structured by

movement between discourses of 'can do' girls and 'at risk' girls. To some extent

these discourses might be said to map onto different girls—that is, girls who are

differently located in relation to class and race—but more than this an oscillation

between these constructions of girls constitutes the discursive field for talking

about all girls. Even the most privileged, the 'top girls' (McRobbie, 2007) who

succeed in becoming high-earning celebrities in the worlds of TV, fashion or pop

music, are often constructed as fragile and troubled, marked by struggles with

weight and eating disorders, alcoholism or drug addiction (see McRobbie (2009) for

a discussion of how these postfeminist disorders might be understood as 'illegible

rage'). Girlhood is thus an unstable category, marked both by 'trouble' and risk,

and by the suggestion of extraordinary capacity.

The promotion of the Girl Effect is striking for the way in which it draws on both

these discourses of girlhood, but with a particular, novel inflection. While girls in

the US are portrayed as active, empowered free agents, girls in the Global South

are depicted as inhabiting a patriarchal order, where their freedoms—such as

Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill feminist review 105 2013 87

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the right to vote, and to own or inherit property—are constrained. In a familiar

neo-imperialist move, Girl Effect campaigns suggest that the barrier to girls is

constituted by 'cultural' beliefs and practices—such as the failure by families in

developing countries to view girls as future economic actors and therefore to

89

invest in their education. ' Girls, it is argued, are kept away from the public sphere 8 Levine, R., Lloyd, C.B.

and Grown, C. (2009) 'Girls

by the burden of domestic chores. They are often required by their families to be count: a global investment

"the water carrier, the wood gatherer and the caretaker of the young, old and I action agenda', http://

www. cgdev. org/content/

sick'.10 The cumulative effects of these practices, it is suggested, mean that girls' publications/detail/

15154, last accessed

life chances are more limited than those of boys. 30 August 2011.

9 Nike Foundation (2009)

It is this gender inequality that the Girl Effect aims to tackle—primarily by 'Girl Effect: your move',

http://www.girleffect.org/

exporting from North to South the very idea of girlhood or feminine adolescence,

media, last accessed 27

in ways that are redolent of the construction of 'childhood' as a cultural category September 2010.

(Aries, 1962; Castaneda, 2002; Burman and Stacey, 2010). At its core the Girl 10 ibid.

Effect seeks to promote in countries of the Global South a notion of female

adolescence as a time free from and prior to marriage and childbearing—to be

spent instead in education. This is captured by one of the initiative's most bold and

powerful claims: the notion that the 'revolution will be led by a 12-year-old

girl'11—a girl who has been 'reached' and 'helped' before 'the ticking clock' has 11 Nike Foundation

12 (n.d.), 'The Girl Effect

seen her married and pregnant and thus can go on to transform her life chances website: The revolution

and those of her community and nation. The Girl Effect website seeks to poster', http://www

.girleffect. org/downloads/

encapsulate this in (yet another) pithy definition: 'Girl Effect, noun. The unique posters/The_Revolution_

Poster.pdf, last accessed

potential of 600 million adolescent girls to end poverty for themselves and the 1 September 2011.

world'.13

12 'The girl effect: the

clock is ticking', http://

www.youtube. com/watch ?

The Giri Effect describes girls in the South as victims of patriarchal culture

v~le8xgFÔJtVg,

(a point we will return to in the conclusion), but it also, as the above quotes last accessed

5 August 2013.

make clear, describes them as subjects of extraordinary potential (Dogra, 2011).

13 Nike Foundation

Indeed, the contrast between girls' powerlessness and their exceptional capacity (2011) 'Girl Effect

is a rhetorical device infusing a range of 'Girl Effect' media outputs. The Nike website', http://www

.girleffect.org,

Foundation's media outputs repeatedly deploy the slogan 'invest in a girl and last accessed

27 September 2010.

she'll do the rest',14 while the UN Foundation purports that '[w]here there's

14 ibid.

a girl, there's a way'.15 Similarly, one of Nike's promotional animation clips

15 UN Foundation

employs an ironic tone (Chouliaraki, 2012) and asserts that the solution to the (2011a) 'Girl Up website',

world's problems is not to be found in 'money', 'science' or 'the government' but in http://www.girlup.org/,

, ■ I, 16 last accessed

a girl'. 30 August 2011.

16 'The girl effect',

It is important to note that this rhetoric is not reserved for the media outputs http://www.youtube. com/

watch?v=WlvmE4_KMNw,

aimed at popular consumption, but can be found throughout the policy and last accessed

5 August 2013.

political interventions too. Indeed, the rhetoric of the Girl Effect is strikingly

different from the usual discursive register of policy documents, characterised by

linguistic styles that are much more familiar from advertising and marketing—bold

claims, hyperbole, rhetorical contrasts, emotional appeals, etc—indicating what

Andrew Wernick (Wernick, 1991) has called the spread of 'promotional culture'

88 feminist review 105 2013 'the revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl'

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

17 We would argue that throughout the polity.17 For example, normally sober and cautious UN bodies call to

this is particularly and

distinctively a reflection

"Unleash the Power of Girls'18 and claim that deprived adolescent girls are 'the

19

of the pivotal role Nike unexpected solution to many of the world's most pressing problems'. Thus, claims

plays in the initiative, with

its commitment to girls regarding the extraordinary capacity and potency of adolescent girls permeate the

now forming a central part

of its global brand

policy literature. This is not simply the 'girling' of development but its 'girl

image—something that powering', seeking to export the particular fusion of agency, independence,

would merit extensive

further analysis. consumerism and entrepreneurialism that has become the hallmark of Western

18 UN Interagency discourses of girlhood.

Taskforce on Adolescent

Girls (n.d.) 'Girl power and

One aspect of this celebration of girls' potential is that they are portrayed as a

potential' leaflet,

[online], http://www more worthwhile 'investment' than older women. As the World Bank managing

m nicef.org/adolescence/

files/UNJATF_ director phrased it, '[investing in women is smart economics, and investing in

20

Girls^postcardFINAL

girls, catching them upstream, is even smarter economics'. Because of their

.pdf, last accessed

2 February 2012. youth, girls represent a more lucrative opportunity, an investment that, in the

19 UNFPA (2011) economically orientated rhetoric, is likely to yield 'higher returns'. Girls, however,

'Unleashing the power and

potential of adolescent

are also depicted as more vulnerable than older women, for example through the

girls' Press release, emphasis on practices such as child marriage, and therefore in greater need of

2 March, http://www

. unfpa. org/public/cache/ protection. Somewhat paradoxically, girls 'outdo' older women by being both at

offonce/home/news/pid/

greater risk and representing superior productive potential. This conceptualisation

7324;jsessionid=

1C6B7A464ACBAB2

has several implications. It establishes a dichotomous distinction between younger

26818F4498AE587DA, last

accessed 30 August 2011. and older women at the expense of other social divisions that impact on women's

20 World Bank (2009) lives including those relating to class, sexuality and ethnicity. The emphasis on girls

'Adolescent girls in focus

at the World Economic

as being more 'at risk' undermines the recognition of girls and women's shared

Forum', http://www.go vulnerabilities and the need to protect older women from gender discrimination.

.worldbank.org/

QHPUUOPVyO, last

Finally, by highlighting greater utility of investment in girls, this policy narrative

accessed 30 August 2011. could reinforce a shift of resources away from the adult population that

constitutes the majority of women in the developing world.

'girls mean business1

A striking feature of the Girl Effect is the way it creates novel alliances between

large transnational corporations, national development agencies, charities, and

bodies such as the United Nations and the World Bank. As mentioned earlier, the

term 'Girl Effect' was coined by the Nike Foundation, and it can be seen not simply

as a development initiative (and way to channel tax dollars) but also a significant

part of Nike's global branding and corporate strategy—designed to extend its

markets (particularly in Africa) and to rehabilitate a US/European image tarnished

by accusations of sweatshops and other unfair labour practices (Hayhurst, 2011).

Much could be said about this—both the new alliance of development actors and

Nike's distinctive role within this—but here we seek to focus on two other elements

of the Girl Effect discourse: the construction of girls in developing countries as

'entrepreneurial subjects' hindered by an oppressive culture, and the way in which

'success stories' from 'global' female entrepreneurs are mobilised.

Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill feminist review 10S 2013 89

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

A key feature of these constructions is the notion that 'girls mean business'—as

the international NGO Plan put it.21 In terms that echo the portrayal of US and 21 Plan (2009) 'Because

I am a girl: the state of

European girls, the Girl Effect describes young women in the Global South as the world's girls 2009; girls

in the global economy',

competent neo-liberal subjects who, while oppressed by their 'culture', have

137, http://www.plan

the capacity, with help, to throw off its shackles and to become suc international.org/about

plan/resources/

cessful entrepreneurs. In the original Girl Effect video, the viewer is asked to publications/campaigns/

imagine a girl in poverty, and then to replace the image of 'hunger', 'HIV' and because-i-am-a-girl

girls-in-the-global

'babies' that it assumes will characterise this with a girl who has been given a loan economy-2009, last

accessed 23 August 2011.

to buy a cow.

She uses the profits from the milk to help her family. Pretty soon the cow becomes a herd. And

she becomes the business owner who brings clean water to the village, which makes men

respect her good sense and invite her to the village council, where she convinces everyone

that all girls are valuable. Soon more girls have a chance and the village is thriving. Healthier

babies, peace, lower HIV, food, education, commerce, sanitation, stability. Which means the

economy of the entire country improves and the whole world is better off." 22 'The girl effect',

http://www.youtube. com/

watch?v=WlvmE4_KMNw,

In this simple narrative, told and retold across multiple iterations of the Girl Effect,

last accessed 5 August

neo-liberalism is portrayed as the liberating force through which patriarchy can be 2013.

defeated. Once they are unleashed, girls' entrepreneurial spirits can instantly

overturn hundreds of years of patriarchy and transform the economic fortunes of

the whole world. Following Cornwall, Harrison and Whitehead's influential notion of

'feminist development fables' (2007), Heather Switzer aptly describes this narrative

as a '(post)feminist development fable'.

Indeed, within the Girl Effect the celebration of neo-liberal entrepreneurialism

is such that even a struggle with extreme poverty can be cast in terms of

empowerment. A Nike Foundation report vividly illustrates this when it claims that

'A girl living in poverty is already an entrepreneur-in-training. To simply survive,

she has already learned to be resourceful. A negotiator. A networker ... [s]he

could be further down the path of economic possibility than she—or anyone

else—realizes'.23 Poverty, it seems, can be celebrated for the entrepreneurial 23 Nike Foundation

(2009) 'Girl effect: your

capacities it stimulates. The structural dimensions of poverty remain unacknow move', 34, http://www

.girleffect.org/media, last

ledged, as does the potential role played by First World institutions such as the

accessed 27 September

IMF in bringing about the poverty with which women (and men) struggle (Mohanty, 2010.

2003; Hartsock, 2006).

As Wilson (2011) has argued, these kinds of constructions are notable for the way

they break with older depictions of 'third world woman' (Mohanty, 1988), often

presented as passive victim. The shift to more 'positive images' of women in the Global

South by international NGOs, donor governments and other development institutions is

partly a response to feminist and anti-racist and anti-imperialist critiques of this

figure, and has led to an almost ubiquitous stress in development materials upon

women's 'agency'. What is at issue, however, as Wilson argues, is the way in which

'agency' becomes linked to a specific modality of neo-liberal entrepreneurialism; the

90 feminist review 105 2013 'the revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl'

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

continuities between contemporary racialised representations of women and girls in

the Global South with earlier representations of '"productive and contented" workers

in colonial enterprises' (Wilson, 2011: 316); and the way in which girls and women's

own collective struggles for social transformation are occluded in this focus upon

individual agency/micro-enterprise. In these depictions, girls are "lifted out' of history

and politics to be recast as individual entrepreneurial subjects.

A similar mixture of neo-liberal, entrepreneurial and postfeminist discourse can be

found in the narratives of the 'girls who made business', that is the successful

women who are corporate executives involved in sponsoring or implementing Girl

Effect initiatives, which form the perfect complement to the micro-finance

strategies promoted. These executives include their own personal narratives in the

reports they help fund, and these play a pivotal role in the Girl Effect's impact. They

represent the success stories that 'prove' that entrepreneurialism is the solution to

global injustice, and present a picture of neo-liberal capitalism as a benign and

benevolent force—especially in the hands of women. Furthermore, these high

earning professional women describe their work as being driven by a strong sense of

gender solidarity. For example, Maria Eitel, then the Nike Foundation's president,

writes that '[a]s a woman and a mother, I couldn't help but consider the accident

of geography and imagine my life (and my daughter's) if I had grown up in Addis

24 Plan (2009) 'Because instead of Seattle'.24

I am a girl: the state of

the world's girls 2009; girls

in the global economy1, Similar claims can be found in an opinion piece by Indra K. Nooyi, Chair and chief

138, http://www

.plan-international.org/

executive officer (CEO) of PepsiCo. Nooyi draws attention to the fact that she was

about-plan/resources/ brought up in India and highlights the role her mother played in her future success.

publications/campaigns/

because-i-am-a-girl The climb to the top of a large multinational corporation is described as being

girls-in-the-giobal

enabled by an ambitious and competitive approach cultivated by a mother who did

economy-2009, last

accessed 23 August 2011. not herself enjoy similar job opportunities. By highlighting her relationship with her

mother, Nooyi recasts the familiar neo-iiberal story of competition and success as

a narrative of female solidarity and empowerment, a solidarity and empowerment

that is now to be extended to other women in developing countries who are—by

dint of being women—'just like' her. It is an impressive rhetorical accomplishment

when the CEO of a multinational corporation can claim solidarity with the world's

poorest and most dispossessed people. Nooyi reveals that gender solidarity is at

the heart of this when she concludes her account with a pledge to 'keep working

toward a world in which girls...can look to the future with the same sense of

25 ibid., 145. possibility my mother instilled in me'.25

26 UN Foundation li matter, and so does she'26

(n.d.b) 'Girlafesto',

http://www.girlup.org/

get-involved/girlafesto One of the key features of the Girl Effect discourse is its address to Northern/

.html, last accessed

Western publics. A range of high-profile public figures have endorsed these efforts.

30 August 2011.

These include Sarah Brown and Cherie Blair (wives of former British Prime Ministers

Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill feminist review 105 2013 91

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Gordon Brown and Tony Blair), Mary Robinson (former Irish President) and

Madeleine Albright, the former US secretary of state. To help engage the public in

the 'Girl Effect', the Nike Foundation created several promotional animation films,

which are circulated online. Through the production and dissemination of a range

of media outputs, widespread public support for this campaign is being solicited.

Within the larger appeal to Western publics, a specific discourse is the one that

takes as its target American teenage girls. In 2010, the UN Foundation, launched a

campaign titled 'Girl Up', which aims to ignite a grass-roots social movement

27

among American girls. Girl Up advocates consist of a range of public figures, 27 UN Foundation

(2010a) 'United Nations

mostly women, located at the nexus of celebrity-charity-public life. Queen Rania Foundation launches Girl

of Jordan is one of the advocates, as well as Judy McGrath, the chairperson and C£0 Up', Press release, 30

September, http://www

of MTV networks. Other public figures involved in the campaign are Nickelodeon's . unfoundation. org/press

center/press-releases/

teen star Victoria Justice and Ivanka Tramp, daughter of entrepreneur and reality 2010/united-nations

28

TV personality Donald Trump. foundation-launches

girl-up.html, last

accessed 30 August 2011.

The 'Girl Up' campaign encourages American girls to take on the cause of girls in

28 UN Foundation

the Global South. They are invited to render their support through their activity (2011a) 'Girl Up website',

http://www.girlup.org/,

in social networks, through financial donations and through fundraising. As part

last accessed 30 August

of the campaign, a 'Unite for Girls Tour' was launched with motivational rallies, 2011.

featuring celebrity advocates, taking place in several large American cities

including New York, Los Angeles, Seattle, Denver and Washington, DC.29 29 UN Foundation

(n.d.a) 'Girl Up blog: unite

for girls tour', http://www

The 'Girl Up' campaign is a significant part of the range of discourses and .girlup.org/blog/?

sites that form part of the broader 'Girl Effect' discourse. Girl Up events and category=unite-for-girls

tour, last accessed 30

promotional material articulate the relationship between American girls and August 2011.

girls in the Global South, revealing the notion of girlhood and North/

South differences that are being promoted. American teenage girls are

portrayed as 'more educated, socially connected and empowered today than

ever before in history'. The vast discrepancy between American girls and girls 30 UN Foundation

(2010a) 'United Nations

in the Global South is highlighted while evoking a universal notion of girlhood as Foundation launches Girl

the basis for solidarity. The website states, 'With Girl Up, you can join the fight Up', Press release, 30

September, http://www

for every girl's right to be respected, educated, healthy, safe and ready to rule .unfoundation.org/press

center/press-releases/

the future. Just like you'.31 American girls are already 'ready to rule the future' 2010/united-nations

and are now alleged to be in a position to try to ensure that girls in developing foundation-launches

girl-up.html, last

countries enjoy similar privileges. accessed 30 August 2011.

31 UN Foundation

The 'oneness' of girls is evoked repeatedly through Girl Up campaigns, as a way of (2011b) 'Girl Up website:

making an impact',

disavowing the tensions and power differences between girls in the US and girls in http://www.girlup. org/

the Global South. While US girls are hailed as donors, and girls in Africa as learn/making-an-impact

.html, last accessed 30

recipients, the campaign stresses that these are girls 'just like you'. The Girl Up August 2011.

website is suffused with the familiar language of girl power, organised around a

simply expressed pride in being a girl, and being part of a social movement 'for

girls, by girls'. Slogans such as 'I am her, she is me' serve further to reinforce this

view of unproblematic identification and solidarity, while necessarily obscuring

92 fe minist review 105 2013 'the revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl'

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

discussion of differences, power, history or social transformation. Indeed, these

are further elided by the use of American slang phrases such as 'BFF' with which

accolade US girls are invited to nominate themselves if they believe they have

made an 'extraordinary contribution'. Charitable giving, then, systematically recast

as an act of identity, friendship and girlie solidarity, expressed through consump

tion and display.

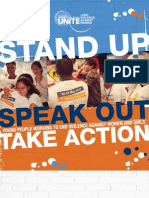

The Girl Up website features a 'Girlafesto' that is downloadable as a poster (see

picture). It can be purchased in the form of a bag and a magnetic sticker. A sense of

'cheekiness' and resistance to power runs through this text. The Girlafesto states:

I AM A GIRL, bright, able, outspoken, soft-spoken, serious, spirited, adventurous, curious and

strong ... i am me. i follow, i lead, i learn, i teach, i change my clothes, my hair, my music

and my mind, i have a voice that speaks, ideas to stand on, and a world to step up to. i

matter, and so does she. she may look different and talk different, but she is like me. SHE IS A

32 UN Foundation GIRL. And together, we will rise up.32

(n.d.b) 'Girlafesto',

http://www.gir/up. org/

get-involved/girlafesto

The American girl is interpellated as empowered, 'outspoken' and 'spirited'. This

.html, last accessed 30

August 2011. empowerment manifests itself, among other things, in her freedom to change her

clothes and her hair. The disempowered girl in the developing world cannot do these

things, yet through the solidarity of American girls and their joint 'rising up', she

too will become free (to change her hair!). The Girlafesto, which was put together

with the advice of market researchers, reveals uncanny similarities with many

contemporary postfeminist style adverts aimed at girls, with a defiant tone, an

assertion of individuality and pride in being female (Gill, 2007a). Indeed, it bears

strong resemblances to a lip gloss advert described by Harris. The advert included

several 'tick-box' statements: 'I have a brain, I have lip-gloss, I have a plan, I have

a choice, I can change my mind, I am a girl' (Harris, 2004: 21-22). The discourse

propagated by Girl Up entails references and connotations specific to the US.

However, the tone and character of the Girlafesto, and the Girl Up campaign more

generally, have broader cultural resonances, particularly in the English-speaking

world. They speak to the 'igeneration' (Gill, in press) shaped by postfeminist

culture, immersion in information and communication technologies—particularly

social networking sites—and individualism. The 'rights' being championed are not

social or collective but relate to consumption, personal growth and individual

conduct—including the much-vaunted 'right' to be contradictory (Dobson, 2011).

In line with this, young women are invited to participate in Girl Up through engaging

in the purchase of commodities (Mukherjee and Banet-Weiser, 2012). As the Girl Up

website puts it, 'support Girl Up with style—buy a Girl Up tee or tote and fill your

33 UN Foundation

bag with a water bottle, pen, magnet and stickers!'.33 Girls are then encouraged to

(2010b) 'Girl Up website:

Girl Up store', http://www celebrate these choices by posting pictures of themselves wearing or carrying Girl

.store.girlup. org/defautt

Up products. Social networking sites have been established specifically to display

these examples of stylish consumption and media-savvy girlhood. Girls are told,

Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill feminist review 105 2013 93

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

'We...want to see you in your Girl Up gear. So, send us a photo of you wearing your .aspx, last accessed 30

August 2011.

shirt, drinking from your water bottle...or post it on our Facebook page!'.34

34 UN Foundation

(2011c) 'Girl Up website:

gear up with Girl Up',

http://www.girlup. org/

GIRIflFESID

GIRLDFESTO blog/gear-up-with-girl

up.html, last accessed 30

August 2011.

IIM R GIRL

OMR GIRL

bright, able, outspoken, soft-spoken.

soft-spta. serious,

serious,

spirited,

spirited,

adventurous,

adventurous,

curious

curious

andand

strong.

strong.

i am me. i follow,

fallow, i lead, i learn, i teach.

i change my clothes, my hain my music

music and

and my

my mind.

mind,

i have a voice that speaks, ideas to stand

stand on,

on, and

and aa world

world to

to step

step up

up to.

to.

matte n

i mattei I! and so does she.

she may loo k different and talk different.

may lool

but she

she is

is like

like me.

me.

SHE IS

SHE IS fl

fl GIRL.

GIRL

And

And together

together we

wewill

willrise

riseup.

up.

Because

Because while

while we

we are

arestrong,

strong,together

togetherweweare

arestronger

stronger

find

And together

together our

our voices

voiceswill

willchange

changeour

ourworld.

world.

—You

—You see

see aa girl.

girl:

WE SEE

W[ SEETHE

THE FUIURE.

FUTURE.

éUNITE

I iUNITEl

GirlUp.org

girluP'

Reproduced with permission from the United Nations Foundation.

Joining the Girl Up movement is not merely an exercise in altruism. It is also

promoted as identity work that will benefit US girls directly—as well as those girls in

94 fe m i n i St re V i e W 105 2013 'the revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl'

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

the Global South it is ostensibly designed to support. Promotional material describes

the campaign as an opportunity for American girls to further their career

opportunities—promising that a Girl Up rally will be 'a globetrotting experience

35 UN Foundation that will turn you and your friends into global leaders'.35 In this way, participation in

(2011d) 'Washington O.C.

unite for girls tour: pep

Girl Up seamlessly blends stylish consumption, networking and social media visi

rally', http://www

bility, with opportunities to enhance one's CV, while also—almost incidentally—

.facebook.com/events/

191107120904746/, last working to empower girls from the Global South who are 'just like you'.

accessed 30 August 2011.

One of the starkest features of the Girl Up discourse is that while it celebrates

individualism, entrepreneurialism and consumption as markers of American girls'

empowerment, it ignores girls' sexual and reproductive rights. The cultural and

political climate in the US, particularly since the Bush presidency, has been one

that undermines girls and young women's freedom to make decisions regarding

their sexual health. The promotion of abstinence-only sex education and more

recently the resurgence of conservative political attacks on abortion rights reveal a

36 New York Times significant threat to the reproductive rights of American women (Schalet, 2011).36

(2012) 'If Roe v. Wade

goes', editorial,

The discourse promoted by Girl Up disregards this reality, purporting instead that

15 October, http://www

girls are more empowered than 'ever before in history'. This denial is particularly

. nytimes. com/2012/10/

16/opinion/if-roe-v glaring considering the centrality of sexual and reproductive rights to the policy

wade-goes.html?

_r-0iadxnni=

rationale at the heart of the Girl Effect, as we discuss in the next section.

l£adxnnlx=

1350756312-HRDlx/

xESbgxkOGHdOtjng, last

accessed 20 October 2012.

empowerment and fertility

Although expressed through notions of 'empowerment', the Girl Effect discourse has

a very concrete biopolitical objective at its core. Adolescence is described as a

crucial period in the lives of girls and one that has a lasting impact on their future

prospects. The main reason for this is the process of sexual and reproductive

maturation that takes place at this stage. In developing countries, Girl Effect

proponents argue, young women often marry shortly after puberty and begin to

have children while in their teens (Buvinic, Guzman and Lloyd, 2007). This pattern is

portrayed as a key factor reinforcing the intergenerational cycle of poverty. The

young girl who becomes a mother interrupts her education, thereby undermining

her future earnings. Furthermore, as a mother, she will pass on her educational

disadvantage and ill health to her children (ibid.). However, if a girl is empowered,

she will resist this path and a positive chain of events will be set in motion. As the

UN Interagency Taskforce proclaims, empowered girls 'will stay in school, marry

later, delay childbearing, have healthier children, and earn better incomes that will

37 UN Interagency Task benefit themselves, their families, communities and nations'.37 Girls' empowerment

Force on Adolescent Girls

(2010) 'Accelerating is a strategy for improving the health and wealth of their countries (Foucault, 1998;

efforts to advance the

Macleod, 2002). It is assumed that education will invariably lead girls to choose to

rights of adolescent girls:

a UN joint statement', delay childbearing and that this crucial postponement will improve their children's

http://www. unicef. org/ health.

Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill femi niSt review 105 2013 95

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

This narrative brushes aside the immense variation in education, marriage and media/files/UN Joints

Statement_Adolescent_

fertility patterns across different developing countries and promotes a single Girls_FINAL.pdf, last

accessed 30 August 2011.

picture of 'life in the Global South' as plagued by 'child marriage', teenage

motherhood and HIV/AIDS. Rather than acknowledge the historical and structural

dimensions of poverty, emphasis is placed on women's domestic role and their high

fertility. Furthermore, proponents of the Girl Effect assume that the life trajectory

they sketch out is the inevitable choice of every empowered woman. The possibility

that some women may value early motherhood, or indeed a large family, remains

unthinkable.

The concern with 'third world woman's' fertility has a long history, dating back to

colonial concerns with the fecundity of indigenous populations (Dogra, 2011).

Policies that tackle girls and women's fertility have been a central component of

development work from its inception, and this emphasis persisted through the

notable shift from coercive population control to an emphasis on reproductive

rights. The Girl Effect can be seen as confirming the continued preoccupation with

fertility coupled with the current emphasis on empowerment and rights (Connelly,

2008).

However, the Girl Effect narrative is rooted not only in changes occurring in the

Global South but also within the social transformations that occurred in the West

during the second half of the twentieth century. The life trajectory being promoted

in the Girl Effect is a relatively recent invention linked to wide-reaching social and

economic changes occurring in the West over the last five decades, including

increased secularisation and the liberalisation of sexual, gender and familial

norms. These changes saw the decline of the Fordist model of family life

characterised by a male breadwinner, a family wage and full-time mothering

(Fraser, 1994; Waldby and Cooper, 2008). The two-salaried family—based on

women's increased participation in the labour force—has replaced the earlier

model. Economic changes such as the decline of manufacturing and the rise of

service industries have also impacted on the gendered and classed life trajectory.

Many Western countries have seen a decline in birth rates with a large number of

professional women delaying childbirth and having fewer children (Gerodetti and

Mottier, 2009; Thomson, Kehily, Hadfield and Sharpe, 2011). It is within this context

that preventing 'teenage motherhood' became a policy objective, replacing the

earlier policy concern with 'unwed mothers' (Arney and Bergen, 1984; Solinger,

1992; Luker, 1996; Koffman, 2012).

The Girl Effect discourse seems to draw heavily on Western policy literature on

adolescent motherhood. The notion that early motherhood disrupts young women's

educational and professional training and sets them on the path for long-term

poverty and ill health is a key feature of this literature (Social Exclusion Unit,

1999). This claim has come under sustained criticism. Scholars argue that policy

makers' concern with adolescent motherhood is linked to the fact that it is

96 feminist review 105 2013 'the revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl'

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

primarily economically disadvantaged young women who bear children in their

teens. Teenage mothers' economic disadvantage, however, precedes the occurrence

of becoming a mother. Deprived young women who opt for motherhood do not fare

any worse than women of similar socioeconomic background who have postponed

childbearing (Lawlor and Shaw, 2002; Duncan, 2007; Arai, 2009). Furthermore,

qualitative research indicates that young women's experience of becoming mothers

is a positive one that is often described as motivating and empowering (Barn

and Mantovani, 2007; Arai, 2009; Rudoe and Thomson, 2009; Duncan, Edwards

and Alexander, 2010). In this context, it is unsurprising that the UK government's

efforts to curb teenage motherhood were unsuccessful despite a considerable

38

38 Department for amount of resources and effort.

Education (2011) 'Teenage

conception statistics for

England 1998-2009', The Girl Effect 'exports' a well-trodden policy narrative that despite decades of

http://www.media

.education.gov.uk/assets/

implementation failed to yield the result policy makers wished for. Having failed to

files/pdf/e/england% make Western young women of disadvantaged backgrounds adopt the proposed life

20under%201S%20and%

20under%2016% trajectory, this narrative has now been directed at girls in developing countries.

20conceptiori%>

20statistics%201998

Taking into account the historical and cultural specificity of this policy agenda

2009%20feb%2020U.pdf, raises significant questions regarding its implementation in vastly different cultural

last accessed

1 September 2011.

and social contexts. This includes, of course, the variation between different

nations and localities within the Global South (Mohanty, 1988, 2003). Rather than

recognise and engage with cultural differences in their multiplicity and complexity,

the Girl Effect proposes that girls in the South need to simply emulate privileged

Western women.

conclusion

In this paper we have discussed the Girl Effect as it materialises in

policy discourses and changed investment priorities for national and

development institutions, and as a distinct form of address to publics

Europe whose support is sought. The Girl Effect, we have sugges

consolidates a number of ongoing shifts that include the neo-libe

development, the growing role of corporate players such as the Nike

the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and, above all, the uptake of po

ideas to create what we have called 'the girl-powering of developm

emphasis on girl power can be seen to operate in constructions of th

'aid', in the kinds of projects supported, and, crucially, in the mod

directed towards governments and potential donors in the Global N

together, these construct 'girl power' as a new 'globalised' commons

new hegemony in development practice.

There is much (more) that could be said about the Girl Effect. As alre

significant role played by corporate bodies is profound. The place

culture and the role of social media are also very important d

Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill feminist review 105

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Furthermore, the shift in the very language of development policy, and the uptake

of rhetorics from marketing and branding, deserves considerably more analysis

than has been possible here. In concluding, however, we wish to highlight a number

of points concerned with the specific issues raised by the girl-powering of

development.

What we have sought to argue is that the Girl Effect literature is suffused with

discourses of girl power, postfeminism and neo-liberalism that have been

circulating in the West for at least two decades. The policy strategies that are

being 'exported' to the Global South are therefore imbued with, and profoundly

shaped by, culturally specific understandings and values. The Girl Effect also

entails an address to girls and women in the West, reinforcing postfeminist notions

of Western women as free from any form of gender discrimination or bias. What is

novel about this address is the way in which the postfeminist characteristic of

evoking feminism and repudiating it at the same time (McRobbie, 2004) is

articulated: in this case the mixture is mapped onto a split between the North

and the South. First World girls are invited to endorse feminism but only in relation

to the South. They themselves are seen as being the most empowered, socially

connected and educated girls in history. The need for social change in gender

relations is entirely displaced onto the less fortunate 'sisters' in the South. This is

of course problematic in the colonial relation of rescue fantasy that it sets up in

relation to the South, but it also does significant performative work in the North. In

emphasising the postfeminist idea that 'all the battles have been won' (for

privileged women in the Global North) it further underscores the move to indivi

dualistic discourses that disavow structural or systemic accounts of inequality.

This is connected to the very specific use of feminist ideas in the Girl Effect

campaign. As others have argued in relation to microfinance and other develop

ment interventions, the feminism invoked is individualistic, cut off from collective

struggles or historical understandings, and tied to postfeminist, neo-liberal and

entrepreneurial ideas (Rankin, 2001; Bee, 2011; Wilson, 2011). Furthermore,

capitalist pursuit of profit is described as being wholly compatible with feminist

activism. Women CEOs, such as PepsiCo's Nooyi, can therefore safely claim that

they are seeking to increase their company's profit and help their sisters at the

same time.

In this context, women in the Global South are constructed as ideal neo-liberal

subjects, more 'responsible' than their male counterparts and more 'worthy' of

investment in a way that therefore—as many have argued—reproduces classed

and colonial ideas about the deserving or undeserving poor: girls are the

'unexpected solution' to 'the world's problems' as the Girl Effect would have it,

because they will buy a cow, not alcohol or cigarettes.

In addition, the Girl Effect can be seen as feeding into the 'Othering' of the Global

South, a process that is particularly dangerous in the present political climate. As

98 femi niSt review 105 2013 'the revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl'

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

is well documented, the post-9/11 era saw Western societies becoming increasingly

preoccupied with Muslim women and this became the pretext for xenophobic

political mobilisations against Muslim minorities in the West (Scott, 2007;

Bhattacharyya, 2008, 2011) as well as the invasion of Afghanistan (Abu-Lughod,

2002; Hirschkind and Mahmood, 2002). Within public discourse, gender equality

gained salience as a marker distinguishing the (civilised) North from the oppressive

cultures of the South (Razack, 2004; Lewis, 2006; Gill, 2007b; Pedwell, 2010;

Scharff, 2011), a trope that has deep historical roots dating back to colonial times

(Ahmed, 1992; Abu-Lughod, 2002; Fanon, 2004 [I960]). The Girl Effect reinforces

these discourses by depicting the Global South as a homogenous sphere plagued by

patriarchy and 'harmful cultural practices'. Furthermore, Northern and Southern

girls are positioned differently in relation to their 'culture'. While Western girls are

depicted as empowered agents who have culture, girls in the Global South are

(subjected to) 'culture' (Lowe and Lloyd, 1997).

Finally, we want to draw critical attention to the constructed relation of solidarity

that underpins the Girl Effect. As we have seen, the Girl Effect relies for its force on

a repeatedly asserted claim about identification and solidarity between women. It

is on this basis of shared womanhood that one of the richest company directors in

the world can claim common cause with the most hungry or oppressed. While

development practices have taken on board—at least at face value—the critiques

of those who challenged depictions of the 'third world woman', it appears that

similar anti-racist and anti-colonialist critiques of an easy or straightforward

universal solidarity or sisterhood have not been heard. While solidarity among

women may be a laudable aspiration, decades of discussion within feminism about

differences between women (related to sexual orientation, race, geography,

disability, etc.) give the lie to the simple assertion that 'I am her, she is me'. To

challenge the realities of global world order marked by profound injustice, a more

complex politics is required.

acknowledgements

The research on which this paper is based was funded by the Leverhulme Trust. We

would also like to thank Kalpana Wilson, the two anonymous reviewers and the

editors for their helpful comments and suggestions.

authors1 biographies

Dr Ofra Koffman is Leverhulme Postdoctoral Fellow in the Department for Culture

Media and Creative Industries at King's College London.

Professor Rosalind Gill is Professor of Social and Cultural Analysis in the

Department for Culture Media and Creative Industries at King's College London.

Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill feminist review 105 2013 99

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

references

Aapola, S., Gonick, M. and Harris, A. (2005) young Femininity: Girlhood, Power and Social Change,

Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Abu-Lug hod, L. (2002) ' Do muslim women really need saving? Anthropological reflections on cultura

relativism and its others' American Anthropologist, Vol. 104, No. 3: 783-790.

Ahmed, L. (1992) Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate, New Haven: Yale

University Press.

Arai, L. (2009) Teenage Pregnancy: The Making and Unmaking of a Problem, Bristol: Policy Press.

Aries, P. (1962) Centuries of Childhood, New york: Vintage Books.

Arney, W.R. and Bergen, B.J. (1984) 'Power and visibility: the invention of teenage pregnancy' Socia

Science and Medicine, Vol. 18, No. 1: 11-19.

Barn, R. and Mantovani, N. (2007) 'Young mothers and the care system: contextualizing risk and

vulnerability' British Journal of Social Work, Vol. 37, No. 2: 225-243.

Bee, B. (2011) 'Gender, solidarity and the paradox of microfinance: reflections from Bolivia' G ender,

Place & Culture, Vol. 18, No. 1: 23-43.

Bhattacharyya, G. (2008) Dangerous Brown Men: Exploiting Sex, Violence and Feminism in the 'War o

Terror' London: Zed Books.

Bhattacharyya, G. (2011) 'Sex, shopping and security' Feminist Media Studies, Vol. 11, No. 1: 13-20.

Bunting, A. (2005) "Stages of development: marriage of girls and teens as an international huma

rights issue' Social & Legal Studies, Vol. 14, No. 1: 17-38.

Burman, E. (1995) 'The abnormal distribution of development: policies for Southern women and

children' Gender, Place and Culture, Vol. 2, No. 1: 21-36.

Burman, E. and Stacey, J. (2010) 'The child and childhood in feminist theory' Feminist Theory, Vol. 11

No. 3: 227-240.

Buvinic, M., Guzman, J.C. and Lloyd, C.B. (2007) 'Gender shapes adolescence' Development Outreach,

Vol. 9, No. 2: 12-15.

Castaneda, C. (2002) Figurations: Child, Bodies, Worlds, Durham: Duke University Press.

Chant, S. (2006) 'Re-thinking the "feminization of poverty" in relation to aggregate gender indices'

Journal of Human Development, Vol. 7, No. 2: 201-220.

Chorev, N. and Babb, S. (2009) 'The crisis of neoliberalism and the future of international institutions:

a comparison of the IMF and the WTO' Theory and Society, Vol. 38, No. 5: 459-484.

Chouliaraki, L. (2012) The Ironic Spectator: Solidarity in the Age of Post-Humanitarianism,

Cambridge: Polity Press.

Connelly, M. (2008) Fatal Misconception: The Struggle to Control World Population, Cambridge.

Cornwall, A., Harrison, £. and Whitehead, A. (2007) 'Gender myths and feminist fables: the struggle

for interpretive power in gender and development' Development and Change, Vol. 38, No. 1: 1-20.

Croll, E.J. (2006) 'From the girl child to girls' rights' Third World Quarterly, Vol. 27, No. 7: 1285-1297.

Dobson, A.S. (2011) 'The representation of female friendships on young women's myspace profiles:

the all female world and the feminine "other"' in Dunkels, i., Franberg, G.-M. and Hallgren, C.

(2011) editors, youth Culture and Net Culture: Online Social Practices, Hershey, PA: Information

Science Reference.

Dogra, N. (2011) 'The mixed metaphor of "third world woman": gendered representations by

international development NGOs' Third World Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 2: 333-348.

Dricoll, C.A. (2002) Girls: Feminine Adolescence in Popular Culture <I Cultural Theory, New York:

Columbia University Press.

Duncan, S. (2007) 'What's the problem with teenage parents? And what's the problem with policy?'

Critical Social Policy, Vol. 27, No. 3: 307-334.

100 feminist review 105 2013 'the revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl'

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Duncan, S., Edwards, R. and Alexander, C. (2010) editors, 'Conclusion: hazard warning' in Teenage

Parenthood: What's the Problem? London: Tufnell Press, 188-202.

Escobar, A. (2010) Encountering Development: The Making and Unmaking of the Third World, New

Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Fanon, F. (2004 [I960]) 'Algeria unveiled' in Prasenjit, D. (2004 [i960]) editor, Decolonization:

Perspectives from Now and Then, London: Routledge, 42-55.

Foucault, M. (1998) The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: The Mill to Knowledge, London: Penguin.

Fraser, N. (1994) 'After the family wage: gender equity and the welfare state' Political Theory, Vol. 22,

No. 4: 591-618.

Gerodetti, N. and Mottier, V. (2009) 'Feminism(s) and the politics of reproduction' Feminist Theory,

Vol. 10, No. 2: 147-152.

Gill, R. (in press) Creatives: Working in the Cultural Industries, Cambridge: Polity.

Gill, R. (2007a) 'Postfeminist media culture: elements of a sensibility' European Journal of Cultural

Studies, Vol. 10, No. 2: 147-166.

Gill, R.C. (2007b) 'Critical respect: the difficulties and dilemmas of agency and "choice" for feminism'

European Journal of Women's Studies, Vol. 14, No. 1: 69-80.

Goldman, R. (1992) Reading Ads Socially, New York: Routledge.

Harris, A. (2004) Future Girl: Young Women in the Twenty-First Century, London: Routledge.

Hartsock, N. (2006) 'Globalization and primitive accumulation: the contributions of David Harvey's

dialectical marxism' in Castree, N. and Gregory, D. (2006) editors, David Harvey: A Critical Reader,

Oxford: Blackwell, 167-190.

Hayhurst, L.M.C. (2011) ' Corporatising sport, gender and development: postcolonial IR feminisms,

transnational private governance and global corporate social engagement' Third World Quarterly,

Vol. 32, No. 3: 531-549.

Hirschkind, C. and Mahmood, S. (2002) 'Feminism, the Taliban, and politics of counter-insurgency'

Anthropological Quarterly, Vol. 75, No. 2: 339-354.

Independent Commission for Aid Impact. (2012) Girl Hub: A DFID and Nike Foundation Initiative,

London: UK Government.

Johnson, S. (2009) 'Microfinance is dead long live microfinance: critical reflections on two decades

of microfinance policy and practice' Enterprise Development and Microfinance, Vol. 20, No. 4:

291-303.

Koffman, 0. (2012) 'Children having children?: religion, psychology and the birth of the teenage

pregnancy problem' History of the Human Sciences, Vol. 25, No. 1: 119-134.

Lawlor, D.A. and Shaw, M. (2002) 'Too much too young? Teenage pregnancy is not a public health

problem' International Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 31, No. 3: 552-553.

Lewis, G. (2006) 'Imaginaries of Europe: technologies of gender, economies of power' European

Journal of Women's Studies, Vol. 13, No. 2: 87-102.

Lowe, L. and Lloyd, D. (1997) editors, 'Introduction' in The Politics of Culture in the Shadow of

Capital, Durham: Duke University Press, 1-32.

Luker, K. (1996) Dubious Conceptions: The Politics of Teenage Pregnancy, Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Maclean, K. (2012) 'Banking on women's labour: responsibility, risk and control in village banking in

Bolivia' Journal of International Development, Vol. 24, Supplement SI: S100—Sill.

Macleod, C. (2002) 'Economic security and the social science literature on teenage pregnancy in South

Arica' Gender £ Society, Vol. 16, No. 5: 647-664.

McRobbie, A. (2004) 'Post-feminism and popular culture' Feminist Media Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3:

255-264.

McRobbie, A. (2007) 'Top girls?' Cultural Studies, Vol. 21, No. 4-5: 718-737.

Ofra Koffman and Rosalind Gill feminist review 105 2013 101

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

McRobbie, A. (2009) The Aftermath of Feminism: Gender, Culture and Social Change, London: Sage.

Mohanty, C,T. (1988) ' Under Western eyes: feminist scholarship and colonial discourses' Feminist

Review, Issue 30: 61-88.

Mohanty, C.T. (2003) Under Western Eyes" revisited: feminist solidarity through anticapitalist

struggles' Signs, Vol. 28, No. 2: 499-535.

Mukherjee, R. and Banet-Weiser, S. (2012) Commodity Activism: Cultural Resistance in Neoliberal

Times, New york: New York University Press.

Narayan, U. (1995) 'Colonialism and its others: considerations on rights and care discourses' Hypatia,

Vol. 10, No. 2: 133-140.

Pedwell, C. (2010) Feminism, Culture and Embodied Practice: The Rhetorics of Comparison, London:

Routledge.

Rankin, K.N. (2001) 'Governing development: neoliberalism, microcredit, and rational economic

woman' Economy and Society, Vol. 30, No. 1: 18-37.

Razack, S. (2004) 'Imperilled muslim women, dangerous muslim men and civilised Europeans: legal

and social responses to forced marriages' Feminist Legal Studies, Vol. 12, No. 2: 129-174.

Ringrose, J. (2007) 'Successful girls? Complicating post-feminist, neoliberal discourses of educational

achievement and gender equality' Gender and Education, Vol. 19, No. 4: 471-489.

Roy, A. (2002) City Requiem, Calcutta: Gender and the Politics of Poverty, Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press.

Rudoe, N. and Thomson, R. (2009) 'Class cultures and the meaning of young motherhood' in

Graham, H. (2009) editor, Understanding Health Inequalities, 2nd edition, Maidenhead: Open

University Press, 162-178.

Schalet, A.T. (2011) 'Beyond abstinence and risk: a new paradigm for adolescent sexual health1

Women's Health Issues, Vol. 21, No. 3: 5.

Scharff, C. (2011) 'Disarticulating feminism: individualization, neoliberalism and the othering of

"Muslim women'" European Journal of Women's Studies, Vol. 18, No. 2: 119-134.

Scott, J.W. (2007) The Politics of the Veil, Woodstock, UK: Princeton University Press.

Social Exclusion Unit. (1999) Teenage Pregnancy, London: HMSO.

Solinger, R. (1992) Wake Up Little Susie: Single Pregnancy and Race Before Roe v Wade, 2nd edition,

New york; London: Routledge.

Switzer, H. (2010) 'Disruptive discourses: Kenyan Maasai schoolgirls make themselves' Girlhood

Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1: 137-155.

Switzer, H. (2013 - forthcoming) '(Post)feminist development fables: the girl effect and the

production of sexual subjects' Feminist Theory, Vol. 14, No. 3.

Thomson, R., Kehily, M.J., Hadfield, L. and Sharpe, S. (2011) Making Modern Mothers, Bristol: Policy

Press.

Traynor, I. (2012) ' Nato withdrawal from Afghanistan could be speeded up, says Rasmussen', The

Guardian, 1 October.

Waldby, C. and Cooper, M. (2008) 'The biopolitics of reproduction—post-fordist biotechnology and

women's clinical labour' Australian Feminist Studies, Vol. 23, No. 55: 57-73.

Walkerdine, V., Lucey, H. and Melody, J. (2001) Growing Up Girl: Psychosocial Explorations of Gender

and Class, Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wernick, A. (1991) Promotional Culture: Advertising, Ideology and Symbolic Expression, London: Sage.

Wilson, K. (2011) '" Race", gender and neoliberalism: changing visual representations in development'

Third World Quarterly, Vol. 32, No. 2: 315-331.

doi: 10.1057/fr. 2013.16

102 feminist review 10S 2013 'the revolution will be led by a 12-year-old girl'

This content downloaded from

95.107.164.14 on Sun, 03 Oct 2021 21:16:50 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Hildebrand What Is PhilosophyDocument288 pagesHildebrand What Is PhilosophydidiodjNo ratings yet

- Youth and Inequality: Time To Support Youth As Agents of Their Own FutureDocument40 pagesYouth and Inequality: Time To Support Youth As Agents of Their Own FutureOxfamNo ratings yet

- CamgirlsDocument152 pagesCamgirlsluciano_sampaio_2No ratings yet

- (Cass Military Studies) Daniel H. Katz - Defence Diplomacy - Strategic Engagement and Interstate Conflict-Routledge (2020)Document277 pages(Cass Military Studies) Daniel H. Katz - Defence Diplomacy - Strategic Engagement and Interstate Conflict-Routledge (2020)lisaNo ratings yet

- Schuett & Stirk - Concept of The State in International Relations PDFDocument31 pagesSchuett & Stirk - Concept of The State in International Relations PDFlisaNo ratings yet

- Girl Hub: Empowering Adolescent GirlsDocument2 pagesGirl Hub: Empowering Adolescent GirlsADBGADNo ratings yet

- Module-5-The Contemporary WorldDocument24 pagesModule-5-The Contemporary WorldJunesse BaduaNo ratings yet

- Maggie HummDocument21 pagesMaggie HummRajat KumarNo ratings yet

- From Ideas to Impact: A Playbook for Influencing and Implementing Change in a Divided WorldFrom EverandFrom Ideas to Impact: A Playbook for Influencing and Implementing Change in a Divided WorldNo ratings yet

- Empowering Women Through MicrofinanceDocument64 pagesEmpowering Women Through MicrofinanceSocial Justice100% (2)