Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1st Required Reading

Uploaded by

Ms. MarjCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1st Required Reading

Uploaded by

Ms. MarjCopyright:

Available Formats

The Role of Materials in the Language Classroom:

Finding the Balance

This article highlights the delicate balance the materials developer needs to achieve between

expanding classroom horizons and dominating the interaction which underlies

the learning process. Jane Crawford addresses the assumptions about language and learners

which she feels should underpin commercial materials if they are to scaffold

the learning process.

Introduction Preplanned teaching materials -

"What about meeting learner needs? How can a neipmi scairoiu or ueumicmng

coursebook meet the needs of a specific group of

crutch?

students?"

Concern whether pre-prepared materials can meet

T

hese questions, posed by a teacher looking for individual learner needs is part of the dilemma

the first time at Words Will Travel (Clements teachers face in trying to implement learner-centred

language programs in a group setting. This is not a

Downloaded from search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.700090350107379. on 11/13/2022 03:00 AM AEST; UTC+10:00. © TESOL in Context , 1995.

and Crawford 1994), a set of integrated

resources colleagues and I had just spent three years new issue. Over a decade ago, O'Neill (1982) queried

the assumption that each group is so unique that its

developing, set me thinking about the role of

needs cannot be met by materials designed for

preplanned materials and why I have always been

another group. Such a view not only presupposes it is

interested in resource production. It also recalled my

possible to predict the language needs of students

concern, both as a teacher and teacher educator,

beyond the classroom but also ignores the common

about the incoherence of many language programs

linguistic and learning needs of many learners. The

when teachers create their own materials or, as seems

process undertaken in establishing the NSW

more frequently the case, pick and choose from a Certificate of Spoken and Written English, for

range of authentic and published materials and example, tends to confirm this commonality by

worksheets, often originally prepared for other classes. showing that teachers do not vary radically in the

choice of language competencies assigned to learners

This discussion is divided into two sections. The first

of a similar proficiency level.

looks at attitudes to teaching materials, including

textbooks, and explores two opposing points of view. Textbooks nevertheless remain a contentious issue for

For some, commercial materials deskill teachers, rob many teachers and researchers. Littlejohn (in

them of their capacity to think professionally and Hutchinson and Torres 1994: 316), for example,

respond to their students. They are also misleading in claims textbooks "reduce the teacher's role to one of

that the contrived language they contain has little to managing or overseeing preplanned events". A similar

do with reality. For others, the role of teaching negative view emerged during a recent discussion of

the role of textbooks on the Internet (TESL-L [Teachers

materials is potentially more positive. They can, for

of English as a Second Language List], City University

example, be a useful form of professional

of New York). One participant, for example, claimed

development for teachers, and foster autonomous

that textbooks are for poor teachers, those without

learning strategies in students. Such arguments and

imagination. In the same discussion, a Canadian

the proliferation of teaching materials suggest the

colleague suggested there are cultural differences in

issue is not so much whether teachers should use

attitudes to textbooks and referred specifically to "the

commercially prepared materials, but rather what Australian prejudice" against them. One reason for

form these should take so that the outcomes are this prejudice may well be that so many of the ESL

positive for teachers and learners rather than books available are British or American and so

restrictive. The second part of the discussion explores culturally removed from learners in Australia.

eight key assumptions which the author feels should Certainly when asked what they saw as the major

underpin materials if these are to enhance the learning strengths of a recent set of materials (Clemens and

environment of the classroom. Crawford 1994), more than one in three of the

TESOL in Context Volume 5 No 1 June 1995 25

Jane Crawford

participants at introductory workshops explicitly The difference view, on the other hand, sees materials

mentioned the Australian characters, content and as carriers of decisions best made by someone other

contexts (see Table 1). The discussion on TESL-L, than the teacher because of differences in expertise.

however, confirmed that attitudes to textbooks are This view was mentioned by several of the teachers

complex (see Table 2) and represent a mix of participating in the TESL-L debate (see Table 2) who

pedagogical and pragmatic factors and the different argued for the use of published materials on the

weightings given to these in different contexts.

grounds that these are better - and cheaper in terms of

Textbooks, it appears, are acceptable in some sections

cost and effort (McDonough and Shaw 1993) - than

of the Australian language scene (for example in

teachers can produce consistently in the time

ELICOS and many school-based LOTE programs) but

available to them.

not in others (such as primary ESL and many tertiary

language programs). For many, however, both the difference and the deficit

view challenge teachers' professionalism and reduce

It is, of course, relatively easy to criticise published

them to classroom managers, technicians, or

materials. Their very visibility makes them more

implementers of others' ideas. This attitude is not

publicly accountable than those produced by

limited to language teachers. Loewenberg-Ball and

Downloaded from search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.700090350107379. on 11/13/2022 03:00 AM AEST; UTC+10:00. © TESOL in Context , 1995.

teachers. The grounds for criticism are wide ranging.

Not only do published materials make decisions Feiman-Nemser (1988), for example, found that

which could be made by the teacher and/or students preservice primary school teachers in two American

(Allwright 1981) but they often exhibit other universities were taught explicitly that textbooks

shortcomings. Some materials, for example, fail to should be used only as a resource, and that following

present appropriate and realistic language models a textbook is an undesirable way to teach.

(Nunan 1989, Porter and Roberts 1981). Others

Such views seem problematic. Obviously teaching

propose subordinate learner roles (Auerbach and

materials are not neutral and so will have a role to

Burgess 1985) and fail to contextualise language

play in deciding what is learnt (Apple 1992). For this

activities (Walz 1989). They may also foster

reason, it is essential that materials writers be familiar

inadequate cultural understanding (Kramsch 1987).

with the learning and teaching styles and contexts of

Further weaknesses include failure to address

those likely to use their materials, and be able to

discourse competence (Kaplan and Knutson 1993) or

teach idioms (Mola 1993), and lack of equity in exemplify a variety of good practice. In other words,

gender representation (Graci 1989). The fact that the teachers and their experience have a crucial role to

textbook market flourishes despite such criticisms - play in materials production as well as in their critical

Sheldon (1988), for example, reports that, in the US classroom use, and the best writers are probably

alone, 28 publishers offer over 1,600 ESL textbooks - practising teachers. The difference (or is it a

reflects perhaps teachers' understanding that these deficiency?) is thus not in terms of expertise, but in

same shortcomings also occur in teacher-produced access to time and technology. We live in a

materials; indeed, may do so more frequently because multimedia age and educational materials need to be

of the time constraints under which these are of an adequate level of sophistication if the language

prepared. class and learner are not to be devalued. Desk top

publishing facilitates the production of convincing

There appears to be very little research, however, on

print materials, but many teachers still have neither

the exact role of textbooks in the language classroom.

the time, nor access to adequate technology, to create

Allwright (1981) suggests there are two key positions.

The first - the deficiency view - sees the role of 'authentic' audiovisual materials (i.e. videos, cassettes

textbooks or published materials as being to and computer programs which reflect the real-world

compensate for teachers' deficiencies and ensure the products the learners encounter outside the

syllabus is covered using well thought-out exercises. classroom). Without such authenticity, however, it is

Underlying this view is the assumption that 'good' difficult to provide culturally rich input, or to develop

teachers always know what materials to use with a coping strategies that will enable students to take

given class and have access to, or can create, these. advantage of the extracurricular input to which they

They thus neither want, nor need, published materials. have access.

26 TESOL in Context Volume 5 No 1 June 1995

The Role of Materials in the Language Classroom: Finding the Balance

The assumption seems to be that teachers w i l l and clear and theoretically explicit rationales for the

slavishly follow the textbook, let it control the activities proposed.

classroom and what occurs therein, and fail to

Hutchinson and Torres (1994) also see the textbook as

respond to learner feedback or to challenge received

a possible agent for change. This can be achieved if a

ideas contained in the materials. Is such a view

number of conditions are met. Firstly, the textbook

justified and, if teachers do behave in this way, is it

needs to become a vehicle for teacher and learner

realistic to expect them to prepare their own

training. In other words, as well as an explicit and

materials? In any case, as Allwright (1981) points out,

detailed teacher's guide, the student book should

materials may contribute to both goals and content

also include appropriate learning-how-to-learn

but they cannot determine either. What is learnt, and

suggestions. Secondly, the textbook must provide

indeed, learnable, is a product of the interaction

support and help with classroom management, thus

between learners, teachers and the materials at their

freeing the teacher to cope with new content and

disposal. Furthermore, teachers do not necessarily

procedures. Thirdly, the textbook will become an

teach what materials writers write just as learners do

agent for change if it provides the teacher with a clear

not necessarily learn what teachers teach (Luxon

picture of what the change will look like, and clear

1994), perhaps because of differences in perceptions

Downloaded from search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.700090350107379. on 11/13/2022 03:00 AM AEST; UTC+10:00. © TESOL in Context , 1995.

practical guidance on how to implement it in the

of proposed tasks (Block 1994). In one of the few

classroom. Finally, if adopted by a school, a textbook

studies which has actually looked at teacher use of

can result in collegial support and shared

textbooks, Stodolsky (1989) found considerable

responsibility for, and commitment to, the change.

variation which suggests our mistrust of textbooks may

Again we need more research to see whether

be misplaced. She concluded:

preplanned materials actually do change practice or

are simply adapted to maintain the status quo.

... teachers are very autonomous in their textbook

Stodolsky's study of the use of textbooks by social

use and ... it is likely that only a minority of teachers

studies teachers (1989) suggests that innovative

really follow the text in the page-by-page manner

suggested in the literature (p.176). curriculum packages may produce stricter adherence

to content and procedures than standard textbooks,

There is a need for more research into the dynamics of but that teachers frequently make instruction more

textbook use. Appropriate textbooks, for example, teacher-centred by eliminating group projects and the

may actually assist inexperienced teachers to come to use of exploratory, hands-on activities, or those

terms with content and ways of tackling this with focused on higher order mental processes. In other

different learners: words, the textbook writer's aims may be overridden

or vitiated by the teacher's implementation skills

Teachers' guides may provide a helpful scaffold for

(Jarvis 1987) or their reading of the text (Apple 1992).

learning to think pedagogically about particular

content, considering the relationship between what Another function for textbooks that is often

the teachers and students are doing and what

overlooked is their role as a structuring tool.

students are supposed to be learning. This kind of

Communicative language classes are social events,

thinking about ends and means is not the same as

and so, inherently unpredictable and potentially

following the teacher's guide like a script.

threatening to all participants (e.g. Reid 1994). This is

(Loewenberg-Ball and Feiman-Nemser

1988:421, emphasis added). particularly so in periods of change (Luxon 1994) such

as those experienced by teachers implementing new

Donoghue (1992:35) extends this pedagogical role for programs or working with unfamiliar learner types.

textbooks from inexperienced to experienced Learners are, of course, by definition, always facing

teachers. His survey of 76 teachers showed that the enormous and possibly threatening change as their

majority reported using teachers' guides at least once language skills develop. One strategy both teachers

or twice a week, suggesting their potential as "an and students use in dealing with this uncertainty is

essential source of information and support" and a 'social routinisation', the process by which classroom

medium of on-going professional development. This, interaction becomes increasingly stereotyped to

of course, will only occur if teachers' guides include reduce the unpredictability and, thereby, the stress.

adequate information about the materials provided, Materials can play a key role in this process:

TESOL in Context Volume 5 No 1 June 1995 27

Jane Crawford

Textbooks survive .. . and prosper primarily because Effective teaching materials

they are the most convenient means of providing the

structure that the teaching-learning system - Materials obviously reflect the writers' views of

particularly the system in change - requires. language and learning, and teachers (and students)

(Hutchinson and Torres 1994:317). will respond according to how well these match their

A textbook, from this perspective, does not necessarily own beliefs and expectations. If materials are to be a

drive the teaching process, but it does provide the helpful scaffold, these underlying principles need to

structure and predictability that are necessary to make be made explicit and an object of discussion for both

the event socially tolerable to the participants. It also students and teachers. The remainder of this paper

serves as a useful map or plan of what is intended and

looks at the assumptions about language and learning

expected, thus allowing participants to see where a

which the author feels should underpin materials used

lesson fits into the wider context of the language

in language classrooms. Individual end-users w i l l , of

program. Hutchinson and Torres (1994) suggest this is

important because it allows for: course, weight these factors differently, and so need to

adapt the materials to their own context and learners.

(i) Negotiation: the textbook can actually contribute

Downloaded from search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.700090350107379. on 11/13/2022 03:00 AM AEST; UTC+10:00. © TESOL in Context , 1995.

In terms of our present understanding of second

by providing something to negotiate about. This

can include teacher and learner roles as well as language learning, however, effective materials are

content and learning strategies. likely to reflect the following statements:

(ii) Accountability: the textbook shows all

(i) Language is functional and must be

stakeholders "what is being done ... in the closed

and ephemeral world of the classroom".

contextualised.

(iii) Orientation: teachers and learners need to know Language is as it is because of the purposes we put it

what is happening elsewhere, what standards are to. For this reason, materials must contextualise the

expected, how much work should be covered, language they present. Without a knowledge of what

and so on. is going on, who the participants are and their social

Again it is a question of balance. Using a textbook and psychological distance in time and space from the

does reduce some options for learners, but it can also events referred to, it is impossible to understand the

allow for greater autonomy. They can, for example, real meaning of an interaction. In other words,

know what to expect and better take charge of their

language, whether it is input or learner output, should

own learning. It may well be this sense of control

emerge from the context in which it occurs. One

which explains the popularity of textbooks with many

possible way to build a shared context for learners and

students. Consequently, a teacher's decision not to

use a textbook may actually be a "touch of their teachers is to use video drama. Familiarity with

imperialism" - in the words of a TESL-L colleague - the context helps make the language encountered

because it retains control in the hands of the teacher meaningful, and also extends the content of the course

rather than the learners. beyond that other rich source of contextualised

Therefore, despite the frequently expressed language use, the classroom itself. That is to say, the

reservations about published materials, these do not fictitious world of a video drama can provide a joint

need to be a debilitating crutch used only by those focus which is culturally broader than the classroom,

unable to do without. Indeed, the above discussion and which serves as a springboard into other real

suggests that use of appropriate teaching materials can

world contexts. These will need to be negotiated

advantage both teachers and learners. The issue then

carefully, however, because they are not shared by all

is not whether teachers should or shouldn't use such

members of the group. Again it is the teacher who

materials - most do so at some point in their career

(Cunningsworth 1984) - but what form these materials must ensure that a balance is achieved between input

should take if they are to contribute positively to and the reapplication of this to the unique context of

teaching and learning. a given class.

28 TESOL in Context Volume 5 No 1 June 199S

The Role of Materials in the Language Classroom: Finding the Balance

(ii) Language development requires learner Materials, therefore, need to be authentic-like, that is,

engagement in purposeful use of language. "authentic, in the sense that the language is not

artificially constrained, and is, at the same time,

The focus of input and output materials should thus be

amenable to exploitation for language teaching

on whole texts, language in use, rather than on so-

purposes" (MacWilliam 1990:160). Another related

called 'building blocks' to be used at some later date.

aspect of authenticity concerns the classroom

This does not mean there should be no focus on form

interaction to which the materials give rise (Crawford

but rather that this normally comes out of whole texts

1990, Taylor 1994). The more realistic the language,

which have already been processed for meaning.

the more easily it can cater to the range of proficiency

Study of grammar looks at how such texts use the

levels found in many classes. At the same time, the

system to express meaning and achieve certain

proposed activities must be varied and adaptable to

purposes. Depending on the background and goals of

their learners, teachers can decide whether to classroom constraints of time and concentration span.

enhance or reduce this focus on form and the Vernon (1953), for example, found that there was a

language used to do this. For the majority of learners, steep decline in the amount of aural information

however, some explicit discussion of language at the retained during the course of a half-hour transmission,

whole text level is presumably useful and w i l l and that six to seven minutes is probably the optimal

Downloaded from search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.700090350107379. on 11/13/2022 03:00 AM AEST; UTC+10:00. © TESOL in Context , 1995.

contribute positively to the language learning process maximum even for native-speaking viewers. A video

and learner autonomy (Borg 1994). Materials need to drama which contained five-minute episodes would

include such information for students so that they can not, therefore, be authentic in terms of typical TV

be used as references beyond the classroom and programs, but it would be pedagogically practical and

independently of the teacher. efficient in terms of language comprehension.

(Hi) The language used should be realistic (iv) Classroom materials will usually seek

and authentic-like. to include an audio-visual component.

An outcome of our understanding that language is a This is not only because we live in an increasingly

social practice has been an increased call for the use multimedia world in which advances in technology

of 'authentic' materials, rather than the more allow for expanding flexibility in delivery, but also

contrived and artificial language often found in because such materials can create a learning

traditional textbooks (Grant 1987). The problem with environment that is rich in linguistic and cultural

using authentic materials (in Nunan's sense of "any information about the target language. Materials such

material which has not been specifically produced for as video and multimedia allow teachers and learners

the purpose of language teaching" (1989:54) is that it to explore the non-verbal and cultural aspects of

is very difficult to find such materials which scaffold language as well as the verbal. Intonation, gesture,

the learning process by remaining within manageable mime, facial expression, body posture and so on, are

fields. It is also difficult for teachers legally to obtain a all essential channels of communication which not

sufficient range of audiovisual materials of an only help learners understand the verbal language to

appropriate quality and length. The quality of the which they are exposed, but are also an integral part

materials is, nevertheless, important because of its of the system of meaning which they are seeking to

impact on learners and their motivation: learn. The distance created by the video and the

replay/pause options allows for analysis and cross-

Hi-tech visual images are a pervasive feature of cultural comparisons which can then be extended to

young people's lives. Textbooks, worksheets and

members oi the class and local community. Visuals

overheads are a poor match for these other, more

also provide information about the physical context of

complex, instantaneous and sometimes spectacular

the interaction. This crucial comprehension support

forms of experience and learning. In this context, the

occurs particularly with formats such as soap opera,

disengagement of many students from their

curriculum and their teaching is not hard to where there is greater convergence between the audio

understand. Teachers are having to compete more and visual strands than in other video materials such

and more with this world and its surrounding culture as documentaries with voice-overs (MacWilliam

of the image (Hargreaves 1994:75). 1986).

TESOL in Context Volume 5 No 1 June 1995 29

Jane Crawford

(v) In our modern, technologically complex provokes engages learners in purposeful interaction

world, second language learners need to and gives them an opportunity to check their

develop the ability to deal with written as understanding of the requirements of the task.

well as spoken genres.

(vi) Effective teaching materials foster

Reading materials will normally need to cover a range

learner autonomy.

of genres, possibly including computer literacy. These

will emerge from the context and be accompanied by Given the context-dependent nature of language, no

activities and exercises which explore both their language course can predict all the language needs of

meaning in that context and, if appropriate, their learners and must seek, therefore, to prepare them to

schematic structure and language features. The extent deal independently with the language they encounter

to which teachers focus explicitly on the latter will as they move into new situations. The activities and

depend on the needs and goals of their learners, and materials proposed must be flexible, designed to

whether this kind of analysis fits with learning develop skills and strategies which can be transferred

preferences. For many learners, however, these to other texts in other contexts. The materials writer

reading materials will provide models which can be can also suggest follow-up activities to encourage this

Downloaded from search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.700090350107379. on 11/13/2022 03:00 AM AEST; UTC+10:00. © TESOL in Context , 1995.

used to develop familiarity with the structure of such process and to provide additional practice for those

texts, and provide a scaffold to assist with the learners' who need it. This not only assists the teacher in

subsequent attempts to write similar texts. Materials catering for a range of learning styles and levels, but

should be integrated and not require students to write also contributes to developing their teaching

genres which have not already been encountered. repertoire. Learners can likewise be asked to explore

This means that when learners do begin their analysis, the strategies they and their fellow students use and,

they have already had an opportunity to acquire a where appropriate, try new ones.

certain familiarity with the genre. These previous

examples can then be used for additional practice in One of the advantages of talking about language as

identifying the schematic structure and language proposed above, is that such discussion contributes to

features, thus providing learners with an opportunity the development of skills for continued autonomous

to elaborate and revise their interlanguage (Ellis 1989). learning (Borg 1994), and students gain confidence in

their ability to analyse the data available in the

Writing in a second language is sometimes daunting language to which they have access. Making generic

for L2 learners, especially because, as native speakers and cultural aspects of the language explicit and

know, we tend to be less forgiving of grammatical and available to learners in their textbook gives them more

other inaccuracies. Learners need to come to terms control over their learning environment. Another

with this aspect of written language, and develop important aspect of the move to greater self-direction

appropriate strategies for tackling written tasks. Except is the ability to evaluate the performance of oneself

for informal notes, most writing involves more than

and others. Materials, therefore, need to build in self-

one draft. Materials can incorporate learning cycles

assessment tasks which require learners to reflect on

which allow learners to explore choices and options

their progress.

and choose the most appropriate to their purpose

before they begin working on their own. Individual

(vii) Materials need to be flexible enough

writing will usually occur at the end of a number of

to cater for individual and contextual

activities in which learners have (a) worked with

differences.

examples of the genre but with the focus on meaning,

not form; (b) analysed examples of the genre to While language is a social practice, learning a

determine its social purpose and generic structure; (c) language is largely an individual process as learners

built up their knowledge of the topic through seek to integrate newly perceived information into

discussion, reading and so on, so that they have their existing language system. It is essential for

something to write about and have covered the teachers to recognise the different backgrounds,

necessary vocabulary; and (d) engaged in a joint experiences and learning styles that students bring to

construction, either as a whole group or in smaller the language classroom, and the impact these

groups. The discussion such collaborative work experiences have on what aspects of the input are

30 TESOL in Context Volume 5 No 1 June 1995

likely to become intake. In other words, it is to a large improvisation and adaptation, in spontaneous

extent the learners, not the teachers, who control what interaction in the class, and the development of that

is learnt since it is they who selectively organise the interaction (emphasis added).

sensory input into meaningful wholes.

This diversity of response provides classroom teachers Conclusion

with a rich source of potential communication as

In this article I have looked at the roles preplanned

learners and teachers share their reactions to the

teaching materials can play, and argued that their

materials and compare cultural differences. This

contribution need not be debilitating to teachers and

presupposes that the teacher is prepared to adopt an

learners; they can scaffold the work of both teachers

interpretative rather than a transmissive methodology

and learners and even serve as agents of change,

(Wright 1987) and to adapt the materials to the

provided they act as guides and negotiating points,

context in which learning is taking place. Without

opportunities to interact with one another, the rather than straightjackets. In selecting materials, of

teacher, and the language, students will not be able to course, practitioners need to look carefully at the

confront their hypotheses about how the language principles underpinning such materials to ensure they

system is used to convey meaning, and then check contribute positively to the learning environment. This

these intuitions against the understanding of their article outlines eight characteristics which seem

Downloaded from search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.700090350107379. on 11/13/2022 03:00 AM AEST; UTC+10:00. © TESOL in Context , 1995.

fellow students and the teacher. It is this kind of open appropriate in the light of our current understanding of

interaction which helps make explicit the underlying the learning process, and which suggest we take

cultural and linguistic assumptions and values of both advantage, not just of print, but also of different

teachers and learners. Such assumptions and values audiovisual media to enrich the classroom learning

become negotiable when they are made overt. context.

We obviously need much more information about

(viii) Learning needs to engage learners

how we and our students use such materials to

both affectively and cognitively.

facilitate learning. Wright (1987) suggests we teach

The language classroom involves an encounter of with, rather than through, materials, thus being free to

identities and cultures, and it needs to be recognised improvise and adapt in response to learner feedback.

that language learning (particularly in a second

Effective teaching materials, by providing cultural and

language context but increasingly in foreign language

linguistic input and a rich selection of integrated

contexts as the world shrinks) requires the active

activities, are thus a professional tool which can

participation of the whole learner. The integration of

actually assist teachers to be more responsive, both by

new knowledge into the learner's existing language

leaving them time to cater to individual needs and by

system occurs with certainty only when the language

expanding their teaching repertoire. Learners, too, can

is used spontaneously in a communicative

benefit from access to the materials used in class, and

(purposeful) situation to express the learner's own

the control and structure this allows them to put on

meaning. Such real communication, however, implies

their learning. Both teachers and materials writers do,

the engagement of genuine interest and will depend,

of course, walk a tightrope. The teachers' challenge is

in part at least, on the presence of a positive group

to maintain the balance between providing a coherent

dynamic in the classroom. The input from the

materials provides linguistic and cultural preparation learning experience which scaffolds learner

before, or in parallel with, the learner-generated comprehension and production, and modelling

language which is the ultimate goal of the learning effective strategies without losing responsiveness to

process. As O'Neill (in Rossner and Bolitho 1990:155- the unique situation and needs of each learner. The

6) suggests: textbook writers' challenge is to provide materials

which support, even challenge, teachers and learners,

Textbooks can at best provide only a base or a core and present ideas for tasks and the presentation of

of materials. They are a jumping-off point for teacher

language input without becoming prescriptive and

and class. They should not aim to be more than that.

undermining the teacher's and the learner's

A great deal of the most important work in a class

autonomy. It is a fine balancing act.

may start with the textbook but end outside it, an

TESOL in Context Volume 5 No 1 June 1995 31

f

Jane Crawford

References Loewenberg-Ball, D., and S.Feimen-Nemser. 1988.

Using textbooks and teachers' guides: A dilemma

Allwright, R.L. 1981. What do we want teaching

for beginning teachers and teacher educators.

materials for? ELT Journal 36 (1).

Curriculum Inquiry 18 (4): 401-423.

Apple, M. W. 1992. The text and cultural politics.

Luxon, T. 1994. The psychological risks for teachers in

Educational Researcher 21 (7): 4 - 1 1 . a time of methodological change. The Teacher

Auerbach, E.R., and D. Burgess. 1985. The hidden Trainer 8 ( 1 ) : 6 - 9 .

curriculum of survival ESL. TESOL Quarterly 19: M a c W i l l i a m , lain. 1986. Video and language

475-496. comprehension. ELT Journal 40 (2) 1986.

Block, D. 1994. A day in the life of a class: Teacher Reprinted in Richard Rossner and Rod Bolitho, eds.

learner perceptions of task purpose in conflict. 1990. Currents of Change in English Language

System 22 (4): 473-486. Teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 157-

Borg, S. 1994. Language awareness as methodology: 161.

Implications for teachers and teacher training. McDonough, Jo, and Christopher Shaw. 1993.

Language Awareness 3 (2): 61 - 7 1 . Materials & Methods in ELT. Oxford: Basil

Clemens, J., and J. Crawford, eds. 1994. Words Will Blackwell.

Downloaded from search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.700090350107379. on 11/13/2022 03:00 AM AEST; UTC+10:00. © TESOL in Context , 1995.

Travel. Sydney: ELS Pty Ltd. Mola, Andrea J. 1993. Teaching idioms in the second

Crawford, J. 1990. How authentic is the language in language classroom: A case study of college-level

our classrooms? Prospect 6 (1): 47-54. German. ED 355826.

Cunningsworth, A. 1984. Evaluating and Selecting EFL Nunan, D. 1989. Designing Tasks for the

Teaching Materials. London: Heineman Communicative Classroom. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press.

Educational Books.

Donoghue, F. 1992. Teachers' guides: A review of O'Neill, Robert. 1982. Why use textbooks? ELT

Journal 36 (2). Reprinted in Richard Rossner and

their function. CLCS Occasional Papers (30).

Rod Bolitho, eds. 1990. Currents of Change in

Ellis, R. 1989. Sources of intra-learner variability in

English Language Teaching. Oxford: Oxford

language use and their relationship to second

University Press. 148-156.

language acquisition. In Variation in Second

Porter, D., and J. Roberts. 1981. Authentic listening

Language Acquisition: Psycholinguistic Issues. S.

activities. ELT Journal 36 (1).

Gass, C. Madden, D. Preston, and L. Selinker.

Reid, Joy. 1994. Change in the language classroom:

Clevedon: Multilingual Matters. 2: 22 - 45.

Process and intervention. English Teaching Forum

Graci, J.P. 1989. Are foreign language textbooks

32(1).

sexist? An exploration of modes of evaluation.

Sheldon. L. E. 1988. Evaluating ELT textbooks and

Foreign Language Annals 22 (5): 77-86.

materials. ELT Journal 42 (4): 237-246.

Grant, N. 1987. Making the Most of Your Textbook.

Stodolsky, Susan. 1989. Is teaching really by the

London: Longman.

book? In Philip W . Jackson, and Sophie

Hargreaves, A. 1994. Changing Teachers, Changing

Haroutunian-Gordon, eds. From Socrates to

Times. London: Cassell. Software: The Teacher as Text and the Text as

Hutchinson, T., and E. Torres. 1994. The textbook as Teacher. Chicago: The National Society for the

agent of change. ELT Journal 48 (4): 315-328. Study of Education.

Jarvis, J. 1987. Integrating methods and materials: Taylor, D. S. 1994. Inauthentic authenticity or

Developing trainees' reading skills. ELT Journal authentic inauthenticity. TESL-EJ\ (2): 1-12.

41(3):179-184.

Vernon, M. D. 1953. Perception and understanding of

Kaplan, M.A., and E. Knutson. 1993. Where is the instructional television. British Journal of

text? Discourse competence and foreign language Psychology XLIV: 116-126.

textbook. Mid-Atlantic Journal of Foreign Walz, J. 1989. Context and contextualised language

Language Pedagogy 1: 167-176. ED335802. practice in foreign language teaching. Modern

Kramsch, C.J. 1987. Foreign language textbooks' Language Journal 73 (2): 160-168.

construction of foreign reality. Canadian Modern Wright, A. 1987. Roles of Teachers and Learners.

Languages Review 44(1): 95-119. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

TESOL in Context Volume 5 No 1 June 1995

The Role of Materials in the Language Classroom: Finding the Balance

APPENDIX

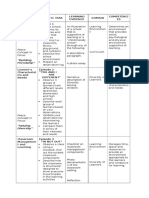

Table 1

What do you see as the major strengths of the What do you see as the major weaknesses of the

materials you have seen today? materials you have seen today?

Australian characters, content, context 90 Too long/too much material 21

Video material 75 Hard to use just bits and pieces/continuous program 19

Wide variety of activities 44 Level too high for stage 2 8

Integrated materials 43 Not suitable for ELICOS/short courses 8

Authentic/realistic/real life 38 Cost 5

Recycling of language 33 Difficult to use with continuous enrolments 3

Entertaining/interesting 27 Insufficient video-based activities 3

Sound methodology/communicative approach 22 Insufficient grammar and structure 3

Good focus on and balance on all skills 21 Stereotyped characters 3

Good audio material 21 Instructions in Student's Book too difficult 3

Relevant to students' lives/needs 13 Poor Student's Book 2

Well structured 12 Not very groovy, won't interest young people 2

Multicultural presentation of language 11 Faked accents 2

Genres presented/well covered 11 Set in NSW 2

Downloaded from search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/ielapa.700090350107379. on 11/13/2022 03:00 AM AEST; UTC+10:00. © TESOL in Context , 1995.

Professional production/high quality materials 9 Speech too Australian and too fast 2

Addresses competencies 8 Insufficient language focuses

Photocopy pages 6 Prefer city-based context (more relevant to students)

Flexibility 6 Readings "a bit difficult"

Useful/suitable/appropriate pronunciation 5 Narrative nature makes the material a bit prescriptive

Presents Australian idioms 5 Insufficient speaking activities

Assessment tasks 5 Teacher's Book unnecessary

Not sufficiently workplace oriented

TOTAL 474 Not relevant to all levels of skills in the class

N = 251 Not sufficiently student-centred

Audio materials too difficult

Not everyone is familiar with genres

No functional grammar activities

TOTAL: 98

Table 2

TESL-L responses in favour of the use of textbooks (& TESL-L responses opposed to the use of textbooks (&

number of times mentioned) TESL-L responses number of times mentioned)

opposed to the use of textbooks (& number of times

(i) Textbooks boring/difficult to understand

mentioned)

(ii) Textbooks don't do what is wanted

(i) Materials better than teacher can produce

consistently in time 5 (iii) Cultural difference - 'the Australian prejudice'

(ii) Textbook can/should be supplemented or adapted 4

(iv) Textbooks are inadequate

(iii) A basis for teacher preparation to meet individual

needs 2 (v) Textbooks are inappropriate to learner-centred

(iv) Why reinvent the wheel? 2 methodology

(v) A source of revision/reference for students 2 (vi) Textbooks appropriate in one context not

(vi) Students expect a textbook 2 appropriate in another

(vii) NOT using a textbook "a touch of imperialism" 1

(viii) Textbooks a basis for negotiation 1 (vii) Textbooks are for poor teachers, those without

(ix) Integrity and authority of books - Ss respect books imagination

more than handouts 1 (viii) Textbooks reinforce teacher-driven syllabus

(x) Textbook provides secure base for individual /reduce teacher response to learner feedback

development 1

(xi) Copyright - rights of materials writers 1 N = 21

(xii) Cost of copying unjustified 1 Countries of origin of posters: Australia, Canada, Holland,

(xiii) Textbooks (with keys) save teachers/learners time 1 Japan, Korea, Malaysia, South America, Switzerland,

(xiv) Texts should be available to teachers as references Thailand, USA

only 1

Jane Crawford is a lecturer in LOTE and TESOL Education at the Queensland University of Technology. She has

taught French, EFL and ESL in Australia, China and Europe. She has recently co-edited (with Jonathan Clemens)

Words Will Travel, an integrated video-based resource for English learners.

TESOL in Context Volume 5 No 1 June 1995 33

You might also like

- Teaching to Diversity: The Three-Block Model of Universal Design for LearningFrom EverandTeaching to Diversity: The Three-Block Model of Universal Design for LearningRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Resource Teachers: A Changing Role in the Three-Block Model of Universal Design for LearningFrom EverandResource Teachers: A Changing Role in the Three-Block Model of Universal Design for LearningNo ratings yet

- Bulletin - January, 15 2023Document4 pagesBulletin - January, 15 2023sthelenscatholicNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning AdvancedDocument12 pagesMachine Learning Advanceddhruvit100% (2)

- HTML Tutorial in BanglaDocument54 pagesHTML Tutorial in BanglaBubun Goutam79% (29)

- SQL Interview Questions 1685537248Document25 pagesSQL Interview Questions 1685537248Aayushi JainNo ratings yet

- (The Essential Guides) Jenny Thompson - The Essential Guide To Understanding Special Educational Needs - Practical Skills For Teachers-Longman (2010)Document137 pages(The Essential Guides) Jenny Thompson - The Essential Guide To Understanding Special Educational Needs - Practical Skills For Teachers-Longman (2010)DuroNo ratings yet

- A History of Indian Literature in EnglishDocument436 pagesA History of Indian Literature in EnglishPriya87% (15)

- 1 Principles of TeachingDocument108 pages1 Principles of TeachingKewkew Azilear100% (2)

- Clil SkillsDocument137 pagesClil SkillsAnndrea Coca GómezNo ratings yet

- Teaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of InquiryFrom EverandTeaching in Blended Learning Environments: Creating and Sustaining Communities of InquiryRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Book Level 2Document56 pagesBook Level 2erika rodriguezNo ratings yet

- Idp - Sy2022-2023 - C. SorianoDocument3 pagesIdp - Sy2022-2023 - C. SorianoCharisma SorianoNo ratings yet

- Presented by Muhammad Abduh: Partnerships With Schools and Community. (Print Photo) - Retrieved FromDocument12 pagesPresented by Muhammad Abduh: Partnerships With Schools and Community. (Print Photo) - Retrieved FromTazqia Aulia ZakhraNo ratings yet

- Presented by Muhammad Abduh: Partnerships With Schools and Community. (Print Photo) - Retrieved FromDocument12 pagesPresented by Muhammad Abduh: Partnerships With Schools and Community. (Print Photo) - Retrieved FromMantap bangauNo ratings yet

- Derek BrannonDocument6 pagesDerek Brannonapi-339779580No ratings yet

- The Fours Knows of Collaborative Teaching Keefe Et AlDocument7 pagesThe Fours Knows of Collaborative Teaching Keefe Et Alapi-394243093No ratings yet

- Http://iainkendari - Ac.idDocument6 pagesHttp://iainkendari - Ac.idt3nee702No ratings yet

- Collaborative LearningDocument12 pagesCollaborative LearningMontenegro Roi VincentNo ratings yet

- Procedure: To Engage Students With Topic To Help With ContextualisationDocument3 pagesProcedure: To Engage Students With Topic To Help With ContextualisationMelania ArdiniNo ratings yet

- Figure 11.1. Comparison of Old and New Paradigms of TeachingDocument3 pagesFigure 11.1. Comparison of Old and New Paradigms of TeachingNara Hari AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Author/Date Topic/Focus/ Concept/ Theoretical Model Approach/ Methodology Context/Setting/ Sample Findings Future ResearchDocument7 pagesAuthor/Date Topic/Focus/ Concept/ Theoretical Model Approach/ Methodology Context/Setting/ Sample Findings Future ResearchKring BalubalNo ratings yet

- No Paper Literature Review Research Method Finding/Discussion/Analysis Conclusion and Implication 1Document20 pagesNo Paper Literature Review Research Method Finding/Discussion/Analysis Conclusion and Implication 1Prima Lestari SitumorangNo ratings yet

- Data Collect 3Document4 pagesData Collect 3api-400377867No ratings yet

- Whole Language PhilosophyDocument4 pagesWhole Language PhilosophySMART COPYNo ratings yet

- Group 8 - Related Works & Project-DesignDocument9 pagesGroup 8 - Related Works & Project-DesignCeline Fernandez CelociaNo ratings yet

- Abdurrahman CIA LiteratureDocument5 pagesAbdurrahman CIA LiteratureABDURRAHMANNo ratings yet

- Ilp Form Semester 3 Mary ArmasDocument14 pagesIlp Form Semester 3 Mary Armasapi-637047815No ratings yet

- cstp1 Calise 7Document7 pagescstp1 Calise 7api-622179314No ratings yet

- Assignment 19178149 Low Resolution PartDocument12 pagesAssignment 19178149 Low Resolution Partapi-368682595No ratings yet

- Terms in Education Regarding TasksDocument1 pageTerms in Education Regarding Tasksapi-482880942No ratings yet

- CSTP 3 Pinkston 050324Document9 pagesCSTP 3 Pinkston 050324api-635818346No ratings yet

- CSTP 1 Uchemefuna 4Document8 pagesCSTP 1 Uchemefuna 4api-434100129No ratings yet

- Fallon Parker Edl273 Cei Assignment-1Document3 pagesFallon Parker Edl273 Cei Assignment-1api-356960425No ratings yet

- PHD Poster PresentationDocument1 pagePHD Poster PresentationHenry Nicholas LeeNo ratings yet

- Fall 2022-FotippopcycleDocument6 pagesFall 2022-Fotippopcycleapi-572860282No ratings yet

- Academic Reading 5.Glossary. ШерстнёваDocument4 pagesAcademic Reading 5.Glossary. ШерстнёваAnastaciaNo ratings yet

- CSTP 3 Watkins 5Document13 pagesCSTP 3 Watkins 5api-528630304No ratings yet

- Diaz CartnalDocument7 pagesDiaz Cartnalapi-297105215No ratings yet

- Decolonization As Pedagogy A Praxis of Becoming in ELT Suresh CanagarajahDocument1 pageDecolonization As Pedagogy A Praxis of Becoming in ELT Suresh CanagarajahIzadora Amador DamacenoNo ratings yet

- Standard 3 AnnoDocument2 pagesStandard 3 Annoapi-355090352No ratings yet

- Hyrons Syllabus FS 1Document5 pagesHyrons Syllabus FS 1Lyn JuvyNo ratings yet

- Hyrons Syllabus FS 1Document5 pagesHyrons Syllabus FS 1Lyn JuvyNo ratings yet

- ELE 101 Assignment 1Document4 pagesELE 101 Assignment 1Johndel FellescoNo ratings yet

- Induction Program Presentation 1Document5 pagesInduction Program Presentation 1api-557161783No ratings yet

- CSTP 1 Fountain FinalDocument9 pagesCSTP 1 Fountain Finalapi-518367210No ratings yet

- Learning EnvironmentDocument2 pagesLearning EnvironmentERMA MAE GABATONo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Plan: Explained The Process of DiffusionDocument21 pagesDaily Lesson Plan: Explained The Process of DiffusionArya StarkNo ratings yet

- Reinventing School Libraries: Alternatives, Models and Options For The Future Ken HaycockDocument6 pagesReinventing School Libraries: Alternatives, Models and Options For The Future Ken HaycockMarília CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- 1Document1 page1Reign Krizia Valero LaquiteNo ratings yet

- CSTP 6 Oliva 5Document11 pagesCSTP 6 Oliva 5api-470564956No ratings yet

- Beaconhouse School System: Explained The Process of DiffusionDocument11 pagesBeaconhouse School System: Explained The Process of DiffusionArya StarkNo ratings yet

- CSTP 3 Rogosic 4Document10 pagesCSTP 3 Rogosic 4api-566253930No ratings yet

- BlogconnectionsDocument2 pagesBlogconnectionsapi-330353202No ratings yet

- Table FS1Document3 pagesTable FS1Satou IshidaNo ratings yet

- CSTP 4 Maki 5Document6 pagesCSTP 4 Maki 5api-556746492No ratings yet

- CTSP 3 Hyatt Sem 4Document12 pagesCTSP 3 Hyatt Sem 4api-529069079No ratings yet

- EL 105 Learning Guide EspirituDocument18 pagesEL 105 Learning Guide EspirituDebong EspirituNo ratings yet

- Group 3 Roles and Responsibilities of Teacher and LearnersDocument15 pagesGroup 3 Roles and Responsibilities of Teacher and LearnersChristine HermosoNo ratings yet

- 4 Eddda 0 e 008 F 21 Efab 0 eDocument3 pages4 Eddda 0 e 008 F 21 Efab 0 eapi-546460291No ratings yet

- CSTP 3 April 9.22.20 3.5Document1 pageCSTP 3 April 9.22.20 3.5Kaitlyn AprilNo ratings yet

- Plasencia cstp3 7Document11 pagesPlasencia cstp3 7api-621922737No ratings yet

- EDUC-126-Module-5 - SUMAMBOT, MARYJEL C.Document29 pagesEDUC-126-Module-5 - SUMAMBOT, MARYJEL C.Maryjel Carlom SumambotNo ratings yet

- CSTP 6 Rogosic 4Document9 pagesCSTP 6 Rogosic 4api-566253930No ratings yet

- Fs 1 SyllabusDocument6 pagesFs 1 SyllabusRebecca Caponong100% (1)

- cstp3 Kim 5Document10 pagescstp3 Kim 5api-622501046No ratings yet

- Educ 3505 Seminar Professional Goals For PracticumDocument2 pagesEduc 3505 Seminar Professional Goals For Practicumapi-639095653No ratings yet

- Report On CLLDocument3 pagesReport On CLLSaluibTanMelNo ratings yet

- Jntuk B.tech 1-1 r13 MechDocument23 pagesJntuk B.tech 1-1 r13 MechKonathala RajashekarNo ratings yet

- 9th Class Full Book McqsDocument7 pages9th Class Full Book McqsAsraRajput02No ratings yet

- Nursery English 1st Term 2080Document8 pagesNursery English 1st Term 2080Small Heart AcademyNo ratings yet

- ROMAN - Guide For Sanskrit Pronunciation 6.0Document6 pagesROMAN - Guide For Sanskrit Pronunciation 6.0Alamelu VenkatesanNo ratings yet

- Fs 1 - The Learner S Development and Environment: Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG MarikinaDocument3 pagesFs 1 - The Learner S Development and Environment: Pamantasan NG Lungsod NG MarikinaMarry DanielNo ratings yet

- Tobii Pro Glasses 3 Developer Guide v1.6Document49 pagesTobii Pro Glasses 3 Developer Guide v1.6naonedNo ratings yet

- Certification: Sharad Gupta Sr. Project ManagerDocument5 pagesCertification: Sharad Gupta Sr. Project ManagerAmit MahajanNo ratings yet

- Grade 9 - Active and Passive ListeningDocument7 pagesGrade 9 - Active and Passive ListeningMary Grace Batayo DucoNo ratings yet

- Javascript WeirdDocument209 pagesJavascript WeirdAdnan KhanNo ratings yet

- Example of Term Paper About ReligionDocument8 pagesExample of Term Paper About Religionafmaadalrefplh100% (1)

- TEST 1 - PASSAGE 3 - To Catch A KingDocument36 pagesTEST 1 - PASSAGE 3 - To Catch A KingTRÂM LÊ KIỀUNo ratings yet

- Simple Machines Worksheet - : AnswersDocument2 pagesSimple Machines Worksheet - : AnswersLouis Fetilo Fabunan100% (2)

- DTC Check - ClearDocument2 pagesDTC Check - ClearEnrique Arevalo LeyvaNo ratings yet

- C - Practical FileDocument21 pagesC - Practical FileKarandeep Singh50% (2)

- File Transfer Protocol - WikipediaDocument1 pageFile Transfer Protocol - WikipediaAtifAliBukhariNo ratings yet

- LESSON 2 - DepEd NEW LESSON PREPARATION STANDARDSDocument12 pagesLESSON 2 - DepEd NEW LESSON PREPARATION STANDARDSAimae Rose BaliliNo ratings yet

- English I Honors Syllabus - Fall 2017Document1 pageEnglish I Honors Syllabus - Fall 2017api-293086432No ratings yet

- Developing Higher Order Thinking Skills (Hots) For ReadingDocument7 pagesDeveloping Higher Order Thinking Skills (Hots) For ReadingAbigail MabborangNo ratings yet

- Declarative Logic Programming With Primitive Recursive Relations On ListsDocument14 pagesDeclarative Logic Programming With Primitive Recursive Relations On ListsNtoane Lekuba-Da CubaNo ratings yet

- 1 Statistics and Probability g11 Quarter 4 Module 1 Test of HypothesisDocument19 pages1 Statistics and Probability g11 Quarter 4 Module 1 Test of HypothesisKarlo LlarenaNo ratings yet

- Anchoring Script 28Document2 pagesAnchoring Script 28Tanishk JainNo ratings yet

- Communication and NPRDocument74 pagesCommunication and NPRabhishekkumar825245No ratings yet