Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HBEC2103 Language & Literacy For Early Childhood

Uploaded by

hidayu mohamoodOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

HBEC2103 Language & Literacy For Early Childhood

Uploaded by

hidayu mohamoodCopyright:

Available Formats

HBEC2103

Language and Literacy for

Early Childhood Education

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

HBEC2103

LANGUAGE AND

LITERACY FOR EARLY

CHILDHOOD

EDUCATION

Abdul Hameed Abdul Majid

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

Project Directors: Prof Dr Widad Othman

Dr Aliza Ali

Open University Malaysia

Module Writer: Abdul Hameed Abdul Majid

Moderator: Teh Lai Ling

Open University Malaysia

Enhancer: Falilnesa Mohamed Arfan

Developed by: Centre for Instructional Design and Technology

Open University Malaysia

First Edition, November 2011

Second Edition, December 2019 (MREP)

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM), December 2019, HBEC2103

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without

the written permission of the President, Open University Malaysia (OUM).

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

Table of Contents

Course Guide ixăxiv

Topic 1 Languange Development in Children 1

1.1 Differences in Individual Abilities 2

1.1.1 Health and Physical Development 2

1.1.2 Social-emotional Development 3

1.1.3 Cognitive Development 4

1.2 Stages of Language Development 7

1.2.1 Babies, Newborn to Six Months 7

1.2.2 Babies Aged Six to 12 Months 8

1.2.3 Toddlers Aged 12 to 18 Months 9

1.2.4 Toddlers Aged 18 Months to Two Years 9

1.2.5 Children at Daycare Aged Two to Three Years 10

1.2.6 Daycare Children Aged Three to Four Years 11

1.2.7 Preschool Children Aged Four to Five Years 11

1.2.8 Preschool Children Aged Five to Six Years 12

1.3 Environment 12

1.3.1 Peer Influence in Language Development 13

1.3.2 Family Influence in Language Development 13

1.3.3 Community Influence in Language Development 14

1.3.4 Influence of Culture in Language Development 15

Summary 16

Key Terms 17

Reference 17

Topic 2 Foundations of Language 18

2.1 Language System 19

2.1.1 Phonetics 19

2.1.2 Syntax 20

2.1.3 Semantics 22

2.1.4 Morphology 22

2.2 Development of Language Structure 24

2.2.1 Development of Speech 24

2.2.2 Individual Differences 25

2.2.3 Language and Thought 25

Summary 27

Key Terms 27

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

iv TABLE OF CONTENTS

Topic 3 Types of Literacy 28

3.1 Definition of Literacy 29

3.2 Types of Literacy 33

3.2.1 Personal Literacy 33

3.2.2 Functional Literacy 35

3.2.3 School Literacy 36

3.2.4 Biliteracy 38

Summary 39

Key Terms 40

References 40

Topic 4 Language and the Curriculum Component 41

4.1 Language and Preschool Curriculum 42

4.1.1 Language Component 42

4.1.2 Learning Objectives and Content and 43

Learning Standards

4.1.3 Language Activities 46

Summary 52

Key Terms 52

References 53

Topic 5 Books and Children 54

5.1 ChildrenÊs Book Genre 55

5.1.1 Traditional Literature 55

5.1.2 Why Do We Use Traditional Literature with 57

Children?

5.2 Choosing ChildrenÊs Books 58

5.2.1 Types of Books 59

5.2.2 Evaluating the Contents of a Book 60

5.2.3 Reading Activities 61

Summary 63

Key Terms 64

Topic 6 Story Telling 65

6.1 Selecting a Story: Factors to Consider 66

6.2 Building Their Own Stories 68

6.2.1 Talking about Experiences 69

6.2.2 Stories of Childhood: Making Your Own Fairy Tales 69

6.3 Telling Their Own Stories 70

6.3.1 Delivery Techniques 71

6.3.2 Planning a Storytelling Activity 73

Summary 74

Key Terms 74

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TABLE OF CONTENTS v

Topic 7 Puppets 75

7.1 Planning Puppet Plays for Children 76

7.1.1 Types of Puppets 77

7.1.2 Materials and Tools to Make Puppets 81

7.1.3 Puppet Making 82

7.2 Planning Puppet Shows 83

7.2.1 Making Arrangements before the Stage Performance 84

7.2.2 Staging a Short Puppet Play 85

Summary 87

Key Terms 87

Topic 8 Literacy Instruction for Minority Students 88

8.1 Literacy Instruction for Minority Students 89

8.1.1 Models of Biliteracy Instruction 89

8.1.2 Issues in Literacy Reading and Instruction 92

Summary 96

Key Terms 97

Topic 9 Language Skills 98

9.1 Listening 99

9.1.1 Listening Experience 99

9.1.2 The Hearing versus Listening Perception 100

9.1.3 Phonological Awareness Skills 101

9.1.4 Activities to Improve Phonological Awareness 102

9.2 Reading 104

9.2.1 Reading Methods 104

9.2.2 Factors Encouraging Reading 108

9.2.3 Activities to Enhance Reading Abilities 109

9.3 Writing 110

9.3.1 Development of Writing 110

9.3.2 Playing with Materials in Writing 111

9.3.3 Environmental Print and Writing 113

Summary 114

Key Terms 115

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

vi TABLE OF CONTENTS

Topic 10 Parent-school Involvement 116

10.1 Parent-school Partnership 117

10.1.1 Types of Parent-school Communications 117

10.2 Helping Parents Strengthen a ChildÊs Language Growth 118

10.3 Helping Parents Understand How Young Children 123

Develop Language and Communication

Summary 126

Key Terms 126

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

COURSE GUIDE ix

COURSE GUIDE DESCRIPTION

You must read this Course Guide carefully from the beginning to the end. It tells

you briefly what the course is about and how you can work your way through

the course material. It also suggests the amount of time you are likely to spend in

order to complete the course successfully. Please refer to the Course Guide from

time to time as you go through the course material as it will help you to clarify

important study components or points that you might miss or overlook.

INTRODUCTION

HBEC2103 Language and Literacy for Early Childhood Education is one of the

courses offered at Open University Malaysia (OUM). This course is worth 3

credit hours and should be covered over 8 to 15 weeks. This course is intended

to give learners a foundation in childhood language learning and literacy. Upon

completing this course, learners will have a grasp of issues related to language

and literacy in early childhood education.

COURSE AUDIENCE

This course is offered to all students taking the Bachelor of Early Childhood

Education with Honours programme. This module aims to impart the basics of

language teaching and literacy. It also prepares learners to execute language

teaching and literacy programmes and also to evaluate the programmes.

As an open and distance learner, you should be acquainted with learning

independently and being able to optimise the learning modes and environment

available to you. Before you begin this course, please ensure that you have the

right course material and understand the course requirements as well as how the

course is conducted.

STUDY SCHEDULE

It is a standard OUM practice that learners accumulate 40 study hours for every

credit hour. As such, for a three-credit hour course, you are expected to spend

120 study hours. Table 1 gives an estimation of how the 120 study hours could be

accumulated.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

x COURSE GUIDE

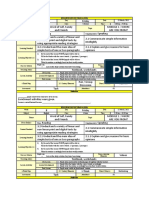

Table 1: Estimation of Time Accumulation of Study Hours

Study

Study Activities

Hours

Briefly go through the course content and participate in initial discussions 3

Study the module 60

Attend 3 to 5 tutorial sessions 10

Online participation 12

Revision 15

Assignment(s), Test(s) and Examination(s) 20

TOTAL STUDY HOURS ACCUMULATED 120

COURSE LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this course, you should be able to:

1. Explain language teaching approaches and techniques;

2. Evaluate language teaching and learning activities; and

3. Plan language teaching and learning activities.

COURSE SYNOPSIS

This course is divided into 10 topics. The synopsis for each topic is listed as

follows:

Topic 1 begins with a discussion on language development. A theoretical view of

language development is presented. The language development in a child

through the different stages i.e. babies, toddlers, children at daycare and

preschool are discussed. How the environment plays a role in shaping language

development is also discussed.

Topic 2 introduces the foundations of language. This topic discusses the

language system. Introduction to phonetics, syntax, semantics and morphology is

systematically presented. The topic moves on to discuss the development of

language structure by highlighting how speech is developed, individual

differences in speech development and concludes with language and thought.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

COURSE GUIDE xi

Topic 3 defines literacy in detail. This topic gives the different views on literacy.

Personal literacy, functional literacy, school literacy and biliteracy are discussed

in detail.

Topic 4 discusses language curriculum and literacy development. Among the

pertinent issues discussed in this topic are language and preschool curriculum

and literacy development. In relation to language curriculum and literacy

development, issues discussed are language components, learning outcomes and

objectives and language activities. As for literacy development, approaches to

reading instructions and development of writing are explored.

Topic 5 looks at books and children. Different book genres are explained.

Children book genres cover both traditional and modern. Books portraying

concepts as well as information will be discussed too. The topic also deals with

how to choose books for children. The different types of books are presented. A

discussion on evaluating book content is also available. Finally, the topic

discusses reading activities for children.

Topic 6 highlights the art of storytelling for children. It deals with how to select

an age-appropriate story for children. Different story types are also presented.

The need to take into consideration childrenÊs language ability is also pointed

out. This topic moves on to explain how to teach children to build their own

stories by talking about their experiences. A discussion about coming up with

childhood stories and creating the childÊs own fairy tale is also examined.

Learners are also introduced to techniques of delivering a story and planning for

a storytelling activity.

Topic 7 introduces learners to puppets in the classroom. Puppets are very useful

in language and literacy development in childhood. This topic demonstrates how

a teacher could plan puppet plays for young children. Prior to that, learners are

introduced to the types of puppets, materials and tools to make puppets and the

art of making a puppet. The topic proceeds with planning for puppet shows.

Finally, planning a stage activity and making arrangements for a puppet show is

introduced.

Topic 8 moves to shed some light on literacy instruction for minority students.

The intricacies in dealing with language and literacy with minority students are

discussed, together with some helpful suggestions. This topic also highlights

different models of biliteracy instruction for children. The topic is concluded

with a discussion of issues in literacy reading and instruction.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

xii COURSE GUIDE

Topic 9 introduces the need for parent-school involvement as a scaffold for the

development of language and literacy in children. Parent-centre partnershipÊs

advantage in supporting language and literacy development is discussed.

Additionally, learners are shown how parents can strengthen a childÊs language

development. Learners are also taught how to produce materials that can help

parents understand language development.

Topic 10 culminates the course by introducing the topic of family literacy and

childhood literacy readiness. Issues of literacy readiness in the family and the

child are highlighted. Finally, the topic ends with a presentation of some models

for intervention to promote literacy readiness in the family and children.

TEXT ARRANGEMENT GUIDE

Before you go through this module, it is important that you note the text

arrangement. Understanding the text arrangement will help you to organise your

study of this course in a more objective and effective way. Generally, the text

arrangement for each topic is as follows:

Learning Outcomes: This section refers to what you should achieve after you

have completely covered a topic. As you go through each topic, you should

frequently refer to these learning outcomes. By doing this, you can continuously

gauge your understanding of the topic.

Self-Check: This component of the module is inserted at strategic locations

throughout the module. It may be inserted after one sub-section or a few sub-

sections. It usually comes in the form of a question. When you come across this

component, try to reflect on what you have already learnt thus far. By attempting

to answer the question, you should be able to gauge how well you have

understood the sub-section(s). Most of the time, the answers to the questions can

be found directly from the module itself.

Activity: Like Self-Check, the Activity component is also placed at various

locations or junctures throughout the module. This component may require you to

solve questions, explore short case studies, or conduct an observation or research.

It may even require you to evaluate a given scenario. When you come across an

Activity, you should try to reflect on what you have gathered from the module and

apply it to real situations. You should, at the same time, engage yourself in higher

order thinking where you might be required to analyse, synthesise and evaluate

instead of only having to recall and define.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

COURSE GUIDE xiii

Summary: You will find this component at the end of each topic. This component

helps you to recap the whole topic. By going through the summary, you should

be able to gauge your knowledge retention level. Should you find points in the

summary that you do not fully understand, it would be a good idea for you to

revisit the details in the module.

Key Terms: This component can be found at the end of each topic. You should go

through this component to remind yourself of important terms or jargon used

throughout the module. Should you find terms here that you are not able to

explain, you should look for the terms in the module.

References: The References section is where a list of relevant and useful

textbooks, journals, articles, electronic contents or sources can be found. The list

can appear in a few locations such as in the Course Guide (at the References

section), at the end of every topic or at the back of the module. You are

encouraged to read or refer to the suggested sources to obtain the additional

information needed and to enhance your overall understanding of the course.

PRIOR KNOWLEDGE

No prior knowledge required.

ASSESSMENT METHOD

Please refer to myINSPIRE.

REFERENCES

Main References

Beaty, J. J., & Pratt, L. (2007). Early literacy in preschool and kindergarten: A

multicultural perspective (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

Merrill/Prentice Hall.

Whitehead, M. R. (2007). Developing language and literacy with young children

(3rd ed.). London, England: Paul Chapman Publishing.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

xiv COURSE GUIDE

Additional References

Machado, J. M. (2005). Early childhood experiences in language arts: Emerging

literacy (7th ed.). Clifton Park, NY: Thomson Delmar Learning.

Nelsen, M. R., & Nelsen-Parish, J. (2002). Peak with books: An early childhood

resource for balanced literacy (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Thomson Delmar

Learning.

Sawyer, W. (2004). Growing up with literature (4th ed.). New York, NY:

Thomson Delmar Learning.

Sowers, J. (2000). Language arts in early education. Melbourne, Australia:

Delmar/Thomson Learning.

TAN SRI DR ABDULLAH SANUSI (TSDAS) DIGITAL

LIBRARY

The TSDAS Digital Library has a wide range of print and online resources for the

use of its learners. This comprehensive digital library, which is accessible

through the OUM portal, provides access to more than 30 online databases

comprising e-journals, e-theses, e-books and more. Examples of databases

available are EBSCOhost, ProQuest, SpringerLink, Books247, InfoSci Books,

Emerald Management Plus and Ebrary Electronic Books. As an OUM learner,

you are encouraged to make full use of the resources available through this

library.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

Topic Language

Development

1 in Children

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of the topic, you should be able to:

1. Explain how physical, social-emotional and cognitive development

account for differences in individual abilities;

2. Identify different stages of language development in children; and

3. Discuss how the environment plays a vital role in shaping language

development in children.

INTRODUCTION

Child development refers to the traits, attitudes and abilities of the child to

progressively perform tasks of greater complexity as he or she advances in years.

Child development is primarily made up of language, social and motor skills.

Even though the sequence at which a child develops is orderly and quite

predictable, not every child will reach language milestones at the same age. It tends

to vary from one child to another.

This introductory topic begins with a discussion on the differences in individual

abilities across three major domains of child development. We will then trace the

various stages of language development that a child goes through, beginning from

baby to toddler, child at daycare right through to preschool. The role of the

environment in fostering language development among young children is also

given due consideration.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

2 TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN

1.1 DIFFERENCES IN INDIVIDUAL ABILITIES

Several factors contribute to the variations in the rate of children development. We

need to understand this well in order to stay unbiased, positive and appreciative

of the uniqueness of a childÊs differing talents, abilities, strengths and relative

weaknesses or deficits, acquired or innate. Given that children between the ages

of two and five are especially vulnerable to these influences, it is imperative that

parents and caregivers alike should be aware and mindful of them as well.

Let us now take a look at some factors responsible for individual differences

among children, namely (refer to Figure 1.1):

Figure 1.1: Factors of individual differences

1.1.1 Health and Physical Development

Physical development is specifically characterised by a childÊs gross and fine

motor skills and balance capabilities demonstrated through activities like catching

a ball, jumping, hopping, skipping, making arts and crafts and playing with

building blocks, among others. These skills make them active and help develop

coordination, control and movement.

However, poor nutrition, physiological health issues combined with weak motor

skills, such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and malnutrition, can

adversely affect a childÊs physical agility. Insufficiently developed vocal cords and

speech related facial muscles will inhibit a childÊs efforts at effective oral

communication. The same applies to fine motor skills which are necessary to write

or draw letters and symbols. An absence in any one area can seriously hinder a

childÊs physical growth and communication skills.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN 3

To illustrate further, a sickly child is not only unable to learn a language properly

but also exhibits regression and backwardness in all types of development.

Prolonged illness and poor health affect both the childÊs level of physical fitness

and hearing, which creates problems with understanding spoken language and

other auditory cues. This, in turn, affects speech and literacy-related development.

In comparison, children who are physically healthy and have properly developed

sensory organs are able to receive correct stimuli from their surroundings and tend

to pick up language quickly and confidently. They have a wholesome personality,

are curious and interested in the environment, and motivated and driven to learn.

1.1.2 Social-emotional Development

Does the child enjoy playing games like „Hide and Seek‰?

Does the child approach other children and offer help?

Does the child take turns when playing games?

Does the child enjoy humour such as being able to laugh at silly faces or

voices?

Does the child reach out to comfort and hug a classmate who is crying or

overwhelmed by something or someone?

These questions represent a decent cross section of social-emotional characteristics

of children that teachers closely look out for and monitor. Your answers to the

questions will serve as a fair indicator of the observable behavioural traits of a

childÊs social-emotional competences portrayed via his or her social and emotional

experience, self-expression, intrapersonal and interpersonal skills, management of

emotions and the ability to establish positive and fulfilling relationships with other

children and adults.

Indeed, children acquire language through interaction ă not just with their parents

but with other adults and children in varying environments. Moreover, no place

is as challenging and telling for young children as the classroom where silence is

not golden. Most of the time, what transpires in the classroom is a reflection and

carryover of what transpires at home.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

4 TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN

Parents have a significant influence on how their children turn out, in terms of

personality, ability to regulate self-conscious emotions such as feelings of

insecurity, constant frustrations and anxieties, including behavioural habits.

Equally important is the manner in which family members bond and communicate

with the child and how much opportunity the child gets to speak, their

encouragement and others which have a direct bearing on the emotional and social

development of the child. A child who feels secure, happy, valued and listened to,

is much more likely to develop a healthy sense of self-identity and competence,

show compassion and emotional intelligence, and experience increasing positive

growth in all other areas of language development and communication, both at

home as well as in the classroom.

Other than helping the child articulate his or her emotions, parental behaviours

also influence how the child learns to understand social roles and rules and to

respond appropriately to the emotions of those around them. If a child has a

difficult time communicating his or her thoughts and desires verbally to others, it

can lead to strained relationships with peers and parents. Consequently, it would

be really hard for the child to get along with and build healthy, prosocial

attachments with other adults throughout life. Besides, language development

issues can spill over to other aspects of his or her learning and cognitive

development.

1.1.3 Cognitive Development

Cognitive development can be defined as how children think, explore and learn to

figure things out. It entails the progressive building of knowledge, learning skills,

problem-solving and dispositions, which serve to enhance childrenÊs ability to

explore, perceive, think about and gain understanding of the world around them.

Through this interplay of genetic and learned factors, children are able to process

sensory information and eventually learn to evaluate, analyse, recall, make

comparisons and understand cause and effect.

Table 1.1 provides a snapshot of typical cognitive activities observed in children

from 0 to 5 years of age.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN 5

Table 1.1: Cognitive Activities in Children Aged 0 to 5 Years

Age Activity

One month Looks at person when spoken to.

Two months Smiles at familiar person talking.

Begins to follow moving person with eyes.

Four months Shows interest in the bottle, breast, familiar toy or new surroundings.

Five months Smiles at own image in mirror.

Looks for fallen objects.

Six months May stick out tongue in imitation.

Laughs at peekaboo game.

Vocalises at mirror image.

May act shy around strangers.

Seven Responds to own name.

months Tries to establish contact with a person by cough or other noise.

Eight Reaches for toys out of reach.

months Responds to „no.‰

Nine months Shows likes and dislikes.

May try to prevent face-washing or other activity that is disliked.

Shows excitement and interest in food or toys that are well-liked.

Ten months Starts to understand some words.

Waves bye-bye.

Holds out arm or leg to help when being dressed.

Eleven Repeats performance that is laughed at.

months Likes repetitive play.

Shows interest in books.

Twelve May understand some „Where is...?‰ questions.

months May kiss on request.

Fifteen Asks for objects by pointing.

months Starts to feed self.

Negativism begins.

Eighteen Points to familiar objects when asked „Where is...?‰

months Mimics familiar adult activities.

Knows some body parts.

Obeys two or three simple orders.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

6 TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN

Two years Names a few familiar objects.

Draws with crayons.

Obeys simple orders.

Participates in parallel play.

Two-and-a- Names several common objects.

half years Begins to take interest in sex organs.

Gives full names.

Helps to put things away.

Peak of negativism.

Three years Constantly asks questions.

May count to 10.

Begins to draw specific objects.

Dresses and undress doll.

Participates in cooperative play.

Talks about things that have happened.

Four years May make up silly words and stories.

Begins to draw pictures that represent familiar things.

Pretends to read and write.

May recognise a few common words, such as own name.

Five years Can recognise and reproduce many shapes, letters, and numbers.

Tells long stories.

Begins to understand the difference between real events and make-

believe ones.

Asks meanings of words.

Source: Adapted from Encyclopedia of ChildrenÊs Health (2019)

On the flip side, cognitive impairment is the general loss or lack of development

of cognitive abilities, particularly autism and learning disabilities. These

limitations can show up in many ways, such as specific difficulties linked to

spoken and written language, coordination, self-control or attention. Such

difficulties extend to schoolwork and can impede learning to read or write or to

do mathematics. A child who has a learning disability may have other conditions,

such as hearing problems or a serious emotional disturbance.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN 7

ACTIVITY 1.1

1. Young children can be affected by physical and social-emotional

factors both in positive and negative ways. Discuss this statement

with your coursemates in the myINSPIRE online forum.

2. Cognitive development is the construction of thought processes,

including remembering, problem-solving and decision-making.

Explain what this means to you and share your thoughts with your

coursemates in the myINSPIRE online forum.

1.2 STAGES OF LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT

In this subtopic, we will learn the stages of language development in children

according to their age. Let us look at this in a detailed manner.

1.2.1 Babies, Newborn to Six Months

Newborn babies up to the age of six months cry in different ways to

communicate their feelings and wants. They cry in different ways to say, „I am

hurt‰, „I am wet‰, „I am hungry‰ or „I am lonely‰. Babies at this stage also make

noises to show displeasure or satisfaction. Babbling is also significant among

babies. Babies tend to look for voices and can recognise familiar faces.

During this stage, language skills can be nurtured by responding with the same

sound when they babble, gurgle and coo. Talking to babies as they are feeding,

dressing or playing is very helpful to nurture their language development. Babies

should be sung to and they love to listen to soft music.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

8 TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN

1.2.2 Babies Aged Six to 12 Months

At this stage, babies are able to wave goodbye and respond when their names are

called. Most often, babies are able to understand the names of familiar objects

around them. They are also able to show interest in picture books and can pay

attention to conversations. Some babies are able to utter their first words at this

stage while others may be slightly delayed. Babies can be seen to babble

expressively as if they are talking. Saying „da-da‰ and „ma-ma‰ are common.

You should nurture the babiesÊ language skill at this stage by teaching them their

names and the names of familiar objects. Talking to them about what is

happening and what you are doing is definitely helpful. Playing peekaboo also

makes them very happy (refer to Figure 1.2). Reading to them while holding out

pictures, magazines or books will greatly spark language development.

Figure 1.2: Playing peekaboo

Source: https://www.rdiconnect.com/co-regulation-the-bridge-to-

communication/peek-a-boo-baby/

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN 9

1.2.3 Toddlers Aged 12 to 18 Months

Starting from the age of 12 months, toddlers are able to identify family members

and familiar objects. They are also able to point to some body parts such as the

nose, ears and eyes. Following simple one-step instructions is now possible. They

start to utter two or more words and can imitate familiar noises like the sound of

cars, planes and birds. Additionally, they are able to repeat a few words and look

at a person talking. Saying „Hi‰ or „Bye‰ if reminded is usual at this stage. They

point to objects if they want them and are able to identify objects in pictures.

Teaching children the names of people, body parts and objects is essential now.

They should be taught the sound of different things around them. Read simple

stories to them. Sit with them and make scrapbooks that have bright colourful

familiar objects. Read to them the contents of the scrapbook. Speak to them clearly

using full simple words. Do not use baby talk at this stage as baby talk confuses

the process of learning to talk.

1.2.4 Toddlers Aged 18 Months to Two Years

Language development grows faster at this stage. They are able to utter about 50

words and can comprehend more. Parrot-like echoing is common. They tend to

imitate single words spoken by others. Toddlers at this age quite commonly jabber

or talk to themselves expressively. More familiar objects are identified and names

uttered. Telegraphic speech containing two to three sentences like „Daddy‰, „Bye-

bye‰ emerge. They try to sing simple songs or hum and even enjoy listening to

short stories, point to more parts of the body and are able to say „Please‰ and

„Thank you‰ if properly prompted.

Reading at least one book a day to children at this stage is most rewarding (refer

to Figure 1.3). Encourage them to repeat short sentences. Start giving them short

instructions. Read rhymes with interesting sounds as they enjoy sounds, actions

and pictures.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

10 TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN

Figure 1.3: It is good for a parent to read daily to a child

Source: https://www.leapfrog.com/en-ie/summer-club/types/articles/when-will-my-

child-learn-to-read

1.2.5 Children at Daycare Aged Two to Three Years

As children approach two to three years of age, they are able to identify up to 10

pictures in a book. Simple sentences and phrases are easily uttered. Children at

this age are able to respond when called by their name and are also able to respond

to simple directions. Their grammar starts to build because they are able to use

plural and past tense forms.

They enjoy simple stories, rhymes and also songs. Their vocabulary will expand to

about 500 words. At this stage, children love to play word games such as „This

Little Piggy‰ or „High as a House‰. It is rewarding for you to continue listening,

reading and talking to them every day. Continue teaching them simple songs and

nursery rhymes.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN 11

1.2.6 Daycare Children Aged Three to Four Years

Speech starts to develop at a faster rate now. Children at this age are able to talk

more. About 75 to 80 per cent of their speech is comprehensible already. They are

able to say their own first and last name. Using prepositions to show locations and

directions become prevalent. Awareness of time is also apparent. At this age,

children start asking questions why, who, what, where, when and how. Speech

becomes clearer with the ability to form sentences with three to five words.

Sentences become more complete. Although they may sometimes stumble over

words, they do not stammer. Listening to stories with familiar words without any

changes is very much enjoyed. They also like to tell simple stories from pictures or

books. They can also recognise colours at this stage.

As a teacher, parent or caregiver, it is absolutely necessary for you to include

children at this age into everyday conversations. Tell them what you plan to do

and ask them lots of questions and listen to them attentively. Start giving them a

few books and teach them how to care for the books.

1.2.7 Preschool Children Aged Four to Five Years

Letter recognition begins to take shape now if they are taught to do so. Some

children are even able to write letters of the alphabet. They are able to recognise

common signboards such as fast food signboards. Speech starts to become more

complex as they are able to utter long, full sentences. Children at this stage enjoy

singing, reciting rhymes and nonsensical words. Interestingly, children at this age

are able to adapt language to the level of their listenerÊs understanding. If they talk

to the caregiver, they may say „Daddy go bye-bye‰ and if they talk to their mother,

they say „Daddy went to the office‰. Ability to remember telephone numbers and

addresses is also quite common at this stage. More colours and shapes are

recognised. Children are also able to follow more than one instruction at this stage.

They also enjoy elaborate conversations and sometimes pick up forbidden words

and tell jokes that are not understood by adults.

It is rewarding to start bringing children of this age to libraries regularly. Always

play games that need colouring and counting. Encourage their language

development by getting them to tell stories and also make their own story books

with magazines, pictures or make scrapbooks. Record their storytelling session or

singing activity as it can motivate them when they listen to themselves.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

12 TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN

1.2.8 Preschool Children Aged Five to Six Years

At the age of five to six years, children start to speak with correct grammar and

word form. They are able to pretend play and are more expressive. Their writing

ability becomes more profound; they can write their own names, some letters and

also numbers. They are also able to read certain simple words.

You should continue reading to them daily. Encourage them to pretend play with

friends using old sheets, cardboard and other household items. Playing „Doctor‰

or „Fireman Sam‰ is very often indulged in by children at this age. Allow them to

be part of what you are doing, especially while carrying out simple tasks such as

cutting out newspaper snippets or arranging books. Get them to find grocery items

at the store.

SELF-CHECK 1.1

1. Why do newborn babies cry in different ways?

2. At what age are toddlers able to identify family members and

familiar objects?

1.3 ENVIRONMENT

The environment plays a role in shaping everything a child does and learns is

undisputable. This is because the environment plays a crucial role in influencing

language development as early as infancy. It starts with the use of language at

home through vocabulary, tone, modelled reading, attitudes about reading and a

print-rich environment that leaves language everywhere. In this subtopic, we shall

explore the factors within the environment that can positively or negatively impact

a childÊs language development.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN 13

1.3.1 Peer Influence in Language Development

Children develop language mostly by listening to speech sounds around them.

Exposing children to as much language as possible during the formative years

have proven to be beneficial. One way to expose them to authentic language is

through interaction with their peers.

Peers act as an important language resource for them especially during the

beginning years, such as their preschool years. Peers are perceived as role models

for children. Generally, children are able to capitalise on their peerÊs language

skills. In fact, they are more at ease and relaxed and converse with and learn from

their peers because unlike parents, peers are more accommodating and

understanding.

While being with their peers, especially with those who have better language

skills, children develop both speech and understanding of words faster. A

classroom which has children with better language skills will definitely enhance

other childrenÊs language acquisition.

1.3.2 Family Influence in Language Development

The family is viewed as an environment that plays a strategic role on childrenÊs

overall development. To begin with, the family is the first social group that is at

the centre of the childÊs identification. Further to that, a family is the first

environment to introduce the concept of values in life. Family members are

significant people who play a role in developing childrenÊs personality. The family

institution facilitates the basic needs of a human in terms of physical, biological,

psychological and social needs; children spend much of their time in the family

environment.

Apart from that, the family institution plays a critical role in moulding or

hindering the childÊs language development. No one can deny that language is an

extremely important tool to possess to interact with people around us. Beginning

with the language from home, children learn to express their feelings, their needs

and confidently ask questions. Language in the family is modified to suit the

childrenÊs situation. For example, when we talk to small children, we use a set of

different words compared to when conducting business or a meeting. Even our

tone is different. We send a message with words, gestures or actions, which

somebody else receives to respond and communicate effectively. All these are

fundamental building blocks towards helping develop a childÊs language.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

14 TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN

Through language spoken by the family, children can connect with others and

make sense of their experiences. A child who does not have a good family

language background will not be exposed to the language input needed in order

to survive and succeed. The familyÊs language shapes a childÊs language

development to reflect the identity, values and experiences of the family and its

community.

Therefore, creating a warm and comfortable environment in which children can

grow to learn the complexities of language is of paramount importance. The

communication skills that children learn early in life will be the foundation for

their communication abilities in future. In short, strong language skills picked up

from the family are an invaluable lifeline that will promote a lifetime of effective

communication.

1.3.3 Community Influence in Language Development

Apart from their peers and family, another factor contributing to childrenÊs

language development is the community itself. The community in which children

live in plays an important role in early language development.

Vocabulary acquisition, for instance, can be promoted by visiting new places in the

community. A visit to interesting places such as zoos, museums and parks

increases and stimulates new vocabulary and language development (refer to

Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4: Parents and child visit a zoo

Source: http://babiestravellite.com/zoo-safety-for-children-and-parents/

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN 15

Children enjoy simple outings such as trips to the local store or to the mall.

These visits play an important role in giving children opportunities to expand their

language experience. By allowing children to get close to language found in

communal places, parents are actually increasing the positive outcome of language

acquisition among children.

1.3.4 Influence of Culture in Language Development

The development of language is very dependent on culture. Babies who are just a

few days old are able to discern one language from another. Children are also pre-

programmed mentally for language development according to different stages.

This development is very much inclined towards oneÊs culture. It means that if a

culture deems that children are to be spoken to only at a particular age, then the

childrenÊs language skills surely will be delayed and even hampered. On the

contrary, if the culture values speaking to children from the onset of birth, then the

children will be able to communicate with ease within the culture.

Culture is unique because it is very specific and has shared knowledge among its

members. Culture is fascinating to learn because it enables communication

between people of different languages. Apart from being an important tool for

communication, language shapes each culture, too. Culture also determines how

one learns. How people learn, how they share knowledge and how they perceive

knowledge may not be the same from one culture to the other.

Our daily routines are also influenced by culture. All our daily endeavours use

language and symbols within certain cultural contexts. Children respond to

situations according to the culture they have been brought up in. If they are

brought up in a culture that respects rules, they will then follow rules. However,

if they are brought up in an environment that does not respect rules, then they may

be outright defiant and possibly react aggressively to symbols of authority. In

other words, the cultural practices surrounding children have great impact on

their learning and language development. Hence, a positive culture with a vibrant

communication between its community members will naturally engender and

accelerate positive language growth.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

16 TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN

SELF-CHECK 1.2

1. How can you, as a preschool teacher, help boost childrenÊs

language acquisition?

2. Explain the parentsÊ role in developing their childÊs language

acquisition.

ACTIVITY 1.2

1. In your opinion, how do peers contribute to a childÊs language

development?

2. What is the effect on language development if a child belongs to a

culture that does not place importance on early language

intervention?

Share your answers with your coursemates in the myINSPIRE online

forum.

Early children development encompasses physical, social-emotional, cognitive

development from 0 to 6 years of age.

The physical, social-emotional and cognitive development of young children

have a direct effect on their overall development.

Physical development in children refers to both the physiological state and

development of their motor skills, which involves using their bodies.

Emotional involvement of parents really does matter and affects the long- term

outcome of their childÊs social-emotional competence and regulation.

The language of family members affects the language development of the

child.

The areas of cognitive development in children include information

processing, intelligence, reasoning, language development and memory.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 1 LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT IN CHILDREN 17

The environment plays a crucial role in influencing language development

from as early as infancy.

It starts with the use of language at home through vocabulary, tone, modelled

reading, attitudes about reading and a print-rich environment that leaves

language everywhere.

A childÊs peers, family, community and culture play a pivotal role in language

development as well.

Children development Family influence

Cognitive development Peer influence

Community influence Physical development

Cultural influence Social-emotional development

Environment

Encyclopedia of ChildrenÊs Health. (2019). Cognitive development. Retrieved

from: http://www.healthofchildren.com/C/Cognitive-Development.html

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

Topic Foundations of

Language

2

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of the topic, you should be able to:

1. Identify the components of the language system;

2. Discuss the development of language structure by highlighting how

speech is developed; and

3. Explain the individual differences in speech development and also in

language and thought.

INTRODUCTION

This topic introduces the foundations of language. Here you will be learn about

the components of the language system which is made up of phonetics, syntax,

semantics and morphology. Next, we will proceed to discuss the development of

language structure by highlighting how speech is developed and what the

individual differences are in speech development. Finally, the discussion

concludes with insights into language and thought.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 2 FOUNDATIONS OF LANGUAGE 19

2.1 LANGUAGE SYSTEM

The language system refers to a system of linguistic units or elements used in a

particular language. Basically, a language system is composed of elements of

phonetics, syntax, semantics and morphology. Each of these elements will be

explained in the following subtopics separately.

2.1.1 Phonetics

Phonetics is the branch of linguistics that deals with human speech, encompassing

the articulatory, acoustic and auditory properties of the sounds of human language

(refer to Figure 2.1). The study of phonetics enables the person learning a language

to discern the sound system of the particular language.

Figure 2.1: Constituents of phonetics

In the English language for example, many non-native English speakers find that

the different English vowels sound the same. The sound „bit‰ and „beat‰, „bid‰

and „bead‰, and groups like „bad‰, „bud‰ and „barred‰ are very problematic for

foreign or second language learners of English.

The study of phonetics facilitates the ability to understand, hear and reproduce

different vowel qualities. Apart from the pronunciation of speech sounds

themselves, another important aspect of phonetics that is often neglected in

foreign language learning and teaching is intonation. Both learners and teachers

often forget that intonation carries meaning and expresses speakersÊ emotions and

attitudes.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

20 TOPIC 2 FOUNDATIONS OF LANGUAGE

When learning a foreign language, students tend to transfer the intonation habits

from their native language into the second language, forgetting that when used

inappropriately, intonation can lead to misunderstanding and even result in

communication breakdown between speakers coming from two different

linguistic backgrounds. This is when phonetics comes in handy. Moreover,

phonetics also describes intonation and helps students to recognise, understand

and practise intonation patterns.

SELF-CHECK 2.1

List the three constituents of phonetics.

2.1.2 Syntax

Syntax is the study of the structure of sentences. Experts describe how words

combine into phrases and clauses and how these then combine to form sentences.

For example, „I found a coin yesterday‰ is embedded as a relative clause in „The

coin which I found yesterday is quite valuable.‰

So, the role of the experts here will be to describe the rules necessary for converting

the first sentence into the second. In linguistics, we can describe the syntax of a

sentence in several ways as follows:

(a) Using the Correct Sequence of the Parts of Speech

For example:

Salleh kicked the ball.

Subject Salleh (followed by a verb „kicked‰).

Object the ball (article the followed by a noun ball)

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 2 FOUNDATIONS OF LANGUAGE 21

(b) Using Transformational Rules

For example:

Salleh kicked the ball.

Sentence Noun Phrase + Verb Phrase Verb

Phrase Verb Phrase + Noun Phrase Noun

Phrase Article + Noun

Verb Phrase = kicked the ball

Noun Phrase = Salleh, the ball

(c) Using Parsing Diagrams

In Parsing Diagrams, a sentence is depicted graphically to emphasise the

hierarchical relationships between the constituents of a sentence (refer to

Figure 2.2).

For example:

Figure 2.2: Parsing Diagram

In this sentence, the is the article, boy is the noun, went is the verb and home

is the noun. The previous example illustrates the basic syntactic structure of

sentences in the English language. By using this method, we can easily

observe how different structures relate to each other.

To sum up rules governing how structure of phrases and how phrases can

be joined are called the syntax of a language. The syntax of a language

however varies across languages, such as the syntax of English may not be

similar to the syntax of the Malay language. However, by using the method

of Parsing, we can study the grammar of any language, for that matter. Even

computer language can be parsed.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

22 TOPIC 2 FOUNDATIONS OF LANGUAGE

2.1.3 Semantics

The systematic study of transmission of meanings in a language is known as

semantics. The study of semantics aims at giving people an understanding of how

language is matched with its intended meaning according to situations. The

following example illustrates a sentence that can semantically mean different

things according to different situations, sometimes with unintended, hilarious

consequences.

We saw the Eiffel Tower flying from London to Paris.

This sentence could mean two things. One, that you saw the Eiffel Tower flying

from London to Paris and the other, you saw the Eiffel Tower while you were

flying in an aeroplane from London to Paris. It really depends on the situation you

are in.

The ambiguities in the sentence arise because in linguistics, lexical or semantic

ambiguities arise out of the fact that a word may have more than one meaning. In

most cases, the intended meaning is made clear by the context. Therefore, the

study of semantics may not be separated from literacy development.

2.1.4 Morphology

Now, let us examine what is meant by morphology. It is that part of the language

system which studies the structure of the word, its components and functions and

also how the word is formed as follows:

(a) Root Words

The root is the main part of the English word. It does not have any prefixes,

suffixes, etc., for example: kind, mix, hope.

(b) Affixes (Prefix and Suffix)

Affixes are added to the root and it changes the meaning. Affixes consist

of prefixes that are placed in front of the root and suffixes which are placed

at the end of the word. Look at the following examples (refer to Table 2.1).

Table 2.1: Root Words and Affixes

Root Word Prefix Suffix

tidy un + tidy = untidy -

kind - kind + ness = kindness

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 2 FOUNDATIONS OF LANGUAGE 23

(c) Morpheme

A morpheme is a meaningful linguistic unit consisting of a word, such as

man or word element, such as -ed in the word „walked‰, that cannot be

divided into smaller meaningful parts.

(d) Phoneme

The phoneme is the smallest unit of the language sound system. Some

examples of phonemes are: /b/, /j/, /o/.

SELF-CHECK 2.2

Define prefix and suffix.

ACTIVITY 2.1

1. Why is semantics vital for literacy development?

2. Fill in the tables below accordingly.

Prefix Two Examples

bi-

im-

non-

dis-

Suffix Two Examples

-able

-est

-fully

-less

Share your answers with your coursemates in the myINSPIRE online

forum.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

24 TOPIC 2 FOUNDATIONS OF LANGUAGE

2.2 DEVELOPMENT OF LANGUAGE

STRUCTURE

Human speech and language development take place most intensively during the

first three years of a childÊs life. This is the time when the brain develops and

matures. Language and speech develop at their best during this stage as children

absorb the rich sounds from the consistent exposure to speech and language from

around them. Like sponge absorbing water, children too absorb just about

everything.

In this subtopic, we will discuss the development of speech in children, their

individual differences in language development and also their language and

thought.

2.2.1 Development of Speech

There is much evidence to show that there are critical periods for speech and

language development in infants and young children. This puts forth the notion

that the developing brain is best able to absorb any language during this critical

period. In this respect, learning a language will be an arduous task, and perhaps

less efficient or effective if these critical periods are allowed to pass without early

exposure to a language.

The way a child starts to communicate is fascinating. From the time they are

newborns, children learn that they will be given food, comfort and companionship

when they cry. Apart from that, they also recognise sounds within their

environment. They grow to distinguish the speech sounds they hear. They are able

to make out words in their language.

Infants are able to recognise basic sounds of their mother tongue by the age of

six months. Infants are able to produce sounds as their speech organs mature. This

sound production begins with cooing a sweetly pitched sound made by infants.

The next step is when the infant starts to babble. Babbling is where infants make

repetitive sounds such as „ba,ba‰, „ma,ma‰ and „da,da‰. This babbling is usually

nonsensical speech. It has tones of human speech but very often does not have any

real words. Nearing the end of the first year, the baby is often able to utter a few

simple words. These words are not understood by them but as soon as the infant

realises that people respond to those words, he or she capitalises on the words by

repeating them to get attention.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 2 FOUNDATIONS OF LANGUAGE 25

Development of speech continues. By 18 months, most children grasp about 10

words. By the age of two, they develop telegraphic speech where two to three word

sentences are uttered. „Daddy go, bye-bye‰ is an example of telegraphic speech.

The development of speech in children continues steadily at the ages of three, four

and five. Their vocabulary increases as they grow and begin to master grammar of

the language.

2.2.2 Individual Differences

The development of language may not be the same for everyone. Each child is an

individual. Some children meet their developmental milestones earlier than

others. It is common to hear people say „She spoke her first word when she was

just seven months‰. „Her brother has not uttered a word and he is two years old‰.

ChildrenÊs language development is a very individual thing as each child develops

at his or her own pace.

Nevertheless, there are certain periods of time when children usually learn to

speak. Just like most children learn to walk between 9 and 15 months, there is no

need to worry if a 13-month-old child has yet to take his or her first steps. The child

may soon walk as he or she may not be ready yet at 13 months. However, if the

child surpasses the normal range of time to start walking i.e. 15 months, then there

is reason for you to be concerned. The child should be taken to a doctor for further

assessment. Similarly, if a child does not show any sign of language development

according to the stages of speech development as suggested in Topic 1, it is

warranted to get the child assessed by clinical specialists who are specifically

trained in various areas of development. These include speech pathologists,

occupational and physical therapists, developmental psychologists and

audiologists.

2.2.3 Language and Thought

Language development can be measured both qualitatively and quantitatively.

Vocabulary development in preschool children is very much linked to the

treatment and experience they get from teachers, parents and the environment.

Children from a deficient language background, where language exposure is

restricted, often face the problem of language development. Children from poor

neighbourhoods are said to face this problem. Conversely, children from homes

that place great importance on language and are supportive of the language needs

of children, have more superior language development.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

26 TOPIC 2 FOUNDATIONS OF LANGUAGE

It is an established fact that language is a tool to gain more understanding. A child

having no language or whose language development is slow will face a hurdle to

develop his or her thoughts. Thus, as an adult, parent, teacher or caregiver, you

have a pivotal role to help children develop their language and thinking. By

interacting with adults, children will use language and understand its role better.

Conversations with adults, for instance, increase the ability of thinking and

understanding among children (refer to Figure 2.3). With continued support of

adults, children will be motivated to acquire and develop communication skills

that will automatically result in the development of language.

Figure 2.3: Coversation between a child and an adult

Source: https://says.com/my/lifestyle/things-parents-should-not-say-to-their-kids

SELF-CHECK 2.3

What is telegraphic speech?

ACTIVITY 2.2

1. As a teacher, how can you reduce the anxiety of a parent who is

overly concerned about his or her childÊs delayed speech

development?

2. Why do children from poor socioeconomic backgrounds lack

language development and thought?

Share your answers with your coursemates in the myINSPIRE online

forum.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 2 FOUNDATIONS OF LANGUAGE 27

A language system comprises mainly of phonetics, syntax, semantics and

morphology.

Phonetics is concerned with the study of the description of isolated speech

sounds.

Semantics is defined as the study of meaning in a language.

Syntax is the study of the structure of sentences. It describes how words,

phrases and clauses combine to form sentences.

Morphology examines the structure of the word, its components and functions

and how the word is formed.

Language and speech develop at their best during the first three years of age.

Children absorb the rich sounds from consistent exposure to speech and

language from around their surroundings.

Individual differences Phonetics

Language structure Semantics

Language system Syntax

Morphology

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

Topic Types of

Literacy

3

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of the topic, you should be able to:

1. Define literacy from traditional and modern perspectives;

2. Discuss how 21st century skills impact teaching and learning of

literacy skills in the early childhood education context; and

3. Explain the significance of the four types of literacy: personal literacy,

functional literacy, school literacy and biliteracy.

INTRODUCTION

There are many skills that are necessary to function in todayÊs world. One such

skill is literacy (Unesco, 2014). In this topic, we will briefly examine salient issues

associated with the traditional representation of literacy alongside the critical

literacy skills required to enable early-years children to cope with the demands of

a world that is becoming increasingly interconnected. The importance and features

of what constitutes personal literacy, functional literacy, school literacy and

biliteracy will be looked at in detail, together with examples of opportunities and

challenges for developing new literacy skills needed by kindergarteners and

preschoolers in the 21st century.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 3 TYPES OF LITERACY 29

3.1 DEFINITION OF LITERACY

Literacy extends beyond the conservative definition of just being able to read and

use printed materials to construct meaning at an extremely basic level. Much more

than that, literacy embraces the ability of the child to use printed and written

information to function in society, to achieve oneÊs goals and to develop oneÊs

knowledge and ultimately participate with others around the world as

technologically-literate global citizens. In view of this, teachers firstly must be able

to make a clear distinction on how information substantially differs from literacy

(refer to Table 3.1).

Table 3.1: Definitions of Information and Literacy

Information Literacy

Knowledge that you get about Ability to identify, understand,

someone or something: facts or details interpret, create, communicate and

about a subject (Merriam Webster compute, using printed and written

Online, n.d.). materials associated with varying

A term with many meanings contexts. Literacy involves continuum

depending on context, but is as a rule of learning in enabling individuals to

closely related to such concepts as achieve their goals, to develop their

meaning, knowledge, instruction, knowledge and potential, and to

communication, representation and participate fully in their community

mental stimulus (Wikipedia, n.d.). and wider society (Unesco, 2014).

Source: Adapted from the Ministry of Education, Malaysia (2019)

In addition to understanding the four types of literacy which will be explained

next, teachers have to be equally alert and sensitive to newly emerging literacy

trends arising from advances in communication and information technology (refer

to Figure 3.1).

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

30 TOPIC 3 TYPES OF LITERACY

Figure 3.1: New literacy skills

These new literacy skills cannot be simply brushed aside because they affect and

form a vital part of our childrenÊs future. Above all, teachers need to be able to

demonstrate how literacy and language development are closely interlinked.

There is no denying that we live in an age of rapid change. TodayÊs children need

more than the traditional 3Rs (reading, writing and arithmetic) to propel them on

a firm path towards developing 21st century skills that focus more on the 4Cs (refer

to Figure 3.2):

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 3 TYPES OF LITERACY 31

Figure 3.2: The 4Cs

Essentially, 21st century skills are a combination of new and old. They encompass

the traditional learning areas of literacy, mathematics, science and social studies,

coupled with critical life skills such as collaboration, problem-solving and

creativity, and career skills such as innovation, technology and global awareness

(refer to Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3: 21st century learners

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

32 TOPIC 3 TYPES OF LITERACY

While some of these 21st century skills may not have immediate relevance for

young children, it is definitely never too early to provide them with a good

foundation in these skills that they need to survive and thrive as 21st century

learners, workers and citizens.

Table 3.2 showcases a number of useful literacy tips to support teachers in

promoting strong 21st century skills among children, especially in areas related to

information and communication, collaboration and creativity.

Table 3.2: Literacy Tips

Tips Description

Online The BBC has excellent interactive videos and resources to get

children to come to grips with reading, writing, spelling,

grammar and listening.

Example: www.bbc.co.uk/skillswise/english

Get blogging Sit together and start a great blog about special events such as

the holidays. This encourages a reflective mindset and provides

a great record to refer back to in the future. Top tip: Make sure

your child does not post inappropriate information!

Example: http://neverseconds.blogspot.com

Play games Some suggestions include Taboo, Scrabble, Hangman,

Articulate! and Boggle. Do not forget to read the rules first!

Conversations At mealtimes, ask each other how the day went. Get better

responses by avoiding questions with yes/no answers and use

„second-level‰ questioning:

Q: What did you enjoy doing today?

A: Art

Q: What was it about Art that you liked doing?

A: We used acrylic paints to draw pictures in the style of

Picasso⁄

Have a laugh Buy a clean joke book and share jokes over the dinner table.

Avoid using the web where jokes may be age-inappropriate.

E-books Encourage gadget-loving reticent readers. Some feature inbuilt

dictionaries, making it quick and easy to look up unfamiliar

words. Starting at around £29 (RM155).

Read by Whether it is a recipe, newspaper or magazine, children typically

example imitate the habits of older people in the family. So pick up a good

book for a Sunday afternoon read!

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 3 TYPES OF LITERACY 33

Reading books Every secondary school student should be able to engage in a

suitable reading book. The key to this is finding a book of

interest. You could start by showing an age-appropriate film and

then finding similar books. For example: the Harry Porter series

by JK Rowling and Bend it like Beckham by Narinder Dhami.

SELF-CHECK 3.1

Schools are beginning to make the shift towards 21st century standards.

What is meant by 21st century skills? What are the skills involved?

3.2 TYPES OF LITERACY

The four types of literacy referred to in this topic are personal literacy, functional

literacy, school literacy and biliteracy. Let us proceed to study each one a little bit

more.

3.2.1 Personal Literacy

Basically, personal literacy denotes an individualÊs ability to read and write.

Generally, childrenÊs ability to read and write differs. Some are able to read and

write at an average age while others start much later.

The development of a childÊs personal literacy depends on factors such as how

early he or she was exposed to reading and writing. There are children who are

exposed very early to reading by their parents through bedtime stories. Their

parents read to them books containing large print and colourful pictures. The

reading experience then progressed to longer stories and fables. There are also

homes enriched with newspapers, magazines, encyclopaedias and a wide selection

of reading materials. On the other hand, there are also homes that do not have a

favourable reading culture. Hence it is hardly surprising for children from homes

with a positive reading culture to develop literacy skills much quickly than those

who do not. Similarly, if a child is taken to the library from a young age to get

acquainted with books and encouraged to get involved with various literacy

activities such as storytelling, vocabulary and colouring activities, his or her

personal literacy level has already been given the right jumpstart.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

34 TOPIC 3 TYPES OF LITERACY

A childÊs personal literacy development also has much to do with the nature and

quality of the learning experience he or she goes through. A child having a positive

and helpful teacher is more inclined to receive adequate scaffolding, become more

motivated and literate. Likewise, a teacher, caregiver or parent who indulges

children with pleasurable and exciting activities will have set the stage for positive

future personal literacy development. In short, a child who experiences

stimulating and pleasurable reading and writing experiences from a very young

age is more likely to grow to be a successful reader and writer. Therefore, it is all

the more crucial for parents, caregivers and teachers to set up an encouraging

literacy development environment for reading and writing by providing fun-filled

and meaningful materials and activities (refer to Figure 3.4).

Figure 3.4: Activity to bolster a childÊs personal literacy

Source: https://www.pinayhomeschooler.com/2019/03/spring-preschool-and-

kindergarten.html

ACTIVITY 3.1

As a parent, what forms of positive personal literacy culture can you

promote at home?

Share your answers with your coursemates in the myINSPIRE online

forum.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 3 TYPES OF LITERACY 35

3.2.2 Functional Literacy

Having discussed personal literacy development in the earlier subtopic, we shall

now move on to look at functional literacy. Functional literacy can be defined in

many ways. One of the definitions is that functional literacy is the basic literacy for

everyday life. In other words, it is the ability of a person to have a basic level of

reading and writing ability to cope and function, either as an adult or child,

depending on the situation.

A person who has functional literacy is said to be able to engage in all the activities

needing literacy for him or her to function efficiently in the community. This

translates to the capability of the person to read and write and comprehend all

necessary information and materials in the community. This ability will ensure his

or her full participation and contribution to the communityÊs development as he

or she is seen as being able to exert a higher degree of control over every day events

compared with others.

As an example, a person who is functionally illiterate will not be able to

comprehend and use to good advantage reading materials pertaining to health

care issues in a community. The inability to perform relatively challenging literacy

tasks will result in a community that is backward and unable to care for and

manage its own pressing health matters as well as that of the environment as a

whole.

ACTIVITY 3.2

We have discussed the importance of functional literacy in terms of

wellness and health care issues in society. In what other ways do you

think functional literacy is important in the community?

Share your answer with your coursemates in the myINSPIRE online

forum.

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

36 TOPIC 3 TYPES OF LITERACY

3.2.3 School Literacy

A literate child is said to be able to communicate by reading, writing, speaking and

also listening. These four skills are interrelated in the sense that the development

of one skill will impact the others.

School literacy development plays an important role in an individualÊs personal

and functional literacy levels. How is this possible?

We know that the key to literacy is reading development; dealing with a

progression of skills such as awareness of letters and sounds (phonics), strategies

for figuring out words, fluency, accuracy and also comprehension. Schools must

therefore consciously incorporate early reading strategies as an integral

component of a schoolwide literacy action plan to improve student engagement

and literacy development across all domains of their academic and social learning.

Over and above holding a school literacy night, displaying learnersÊ group project

work or putting up a talent time show, schools are also tasked with the

responsibility of not just formatting teaching learning activities in typical teacher-

learner interactions but more importantly, to deliver content and values through

computer-mediated instruction via useful kindergarten websites, which of late has

become the favoured medium in early childhood education centres.

To keep up with changing times, let us look at Figure 3.5 for a peek at how both

modes of delivery are specifically integrated into school literacy plans ă designed

to motivate, create and accelerate the childÊs language and literacy development.

Figure 3.5: Engendering collaboration, communication, problem-solving and creativity

Source: https://www.amanceria-kindergarten.com/

Copyright © Open University Malaysia (OUM)

TOPIC 3 TYPES OF LITERACY 37

In addition, schools should set up viable literacy intervention plans to tackle issues

of struggling readers and writers. To this effect, schools could organise literacy-

based activities such as conducting special classes during school hours, personal