Professional Documents

Culture Documents

NOTE5

NOTE5

Uploaded by

XinyiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

NOTE5

NOTE5

Uploaded by

XinyiCopyright:

Available Formats

If we stop to consider it, the great majority of our conscious behavior is acquired through

learning and interacting with other members of our culture. Even those responses to our

purely biological needs (that is, eating, coughing, defecating) are frequently influenced by

our cultures. For example, all people share a biological need for food. Unless a minimum

number of calories is consumed, starvation will occur. Therefore, all people eat. But what we

eat, how often, we eat, how much we eat, with whom we eat, and according to what set of

rules are regulated, at least in part, by our culture.

Clyde Kluckhohn, an anthropologist who spent many years in Arizona and New Mexico

studying the Navajo, provides us with a telling example of how culture affects biological

pomewhat devilish interest in producing a cultural reaction. Guests who came her way were

often served delicious sandwiches filled with a meat that seemed to be neither chicken nor

tuna fish yet was reminiscent of both. To queries she gave no reply until each had eaten his

fill. She then explained that what they had eaten was not chicken, not tuna fish, but the rich,

white flesh of freshly killed rattlesnakes. The response was instantaneous – vomiting, often

violent vomiting. A biological process is caught into a cultural web. (1968: 25–26)

This is a dramatic illustration of how culture can influence biological processes. In fact, in this

instance, the natural biological process of digestion was not only influenced, it was also

reversed. A learned part of our culture (that is, the idea that rattlesnake meat is a repulsive

thing to eat) actually triggered the sudden interruption of the normal digestive process.

Clearly there is nothing in rattlesnake meat that causes people to vomit, for those who have

internalised the opposite idea, that rattlesnake meat should be eaten, have no such

digestive tract reversals.

The effects of culturally produced ideas on our bodies and their natural process take many

different forms. For example, instances of voluntary control of pain reflexes are found

inumerous to cite, but whether we are looking at Cheyenne men engaged in the Sun Dance

ceremony, Fiji firewalkers, or U.S. women practicing the Lamaze (psychoprophylactic)

method of childbirth, the principle is the same: People learn ideas from their cultures that

when internalised can actually later the experience of pain. In other words, a component of

culture (that is, ideas) can channel or influence biologically based pain reflexes.

Ferraro 1998: 19–20

You might also like

- Kluckhohn Queer CustomsDocument7 pagesKluckhohn Queer CustomsCarmen GendrawNo ratings yet

- A History of Cannibalism: From ancient cultures to survival stories and modern psychopathsFrom EverandA History of Cannibalism: From ancient cultures to survival stories and modern psychopathsNo ratings yet

- Schachter, Goldman, & Gordon, 1968Document7 pagesSchachter, Goldman, & Gordon, 1968Ana Sofia AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Enzymes For Health and Longevity - HowellDocument118 pagesEnzymes For Health and Longevity - Howellcobeboss100% (8)

- ANNA WALDSTEIN - Anthropology of FoodDocument9 pagesANNA WALDSTEIN - Anthropology of FoodMariana YañezNo ratings yet

- The Natural Food of Man: Being an attempt to prove from comparative anatomy, physiology, chemistry and hygiene, that the original, best and natural diet of man is fruit and nutsFrom EverandThe Natural Food of Man: Being an attempt to prove from comparative anatomy, physiology, chemistry and hygiene, that the original, best and natural diet of man is fruit and nutsNo ratings yet

- APPSYCH Article CH 10 Why We EatDocument3 pagesAPPSYCH Article CH 10 Why We EatDuezAPNo ratings yet

- Principles of Human FarmingDocument10 pagesPrinciples of Human FarmingRomina LorenaNo ratings yet

- Matthew Cole, Karen Morgan - Veganism Contra Speciesism. Beyond Debate PDFDocument20 pagesMatthew Cole, Karen Morgan - Veganism Contra Speciesism. Beyond Debate PDFCristopherDebordNo ratings yet

- The Female Face of HungerDocument9 pagesThe Female Face of HungerMG DangtayanNo ratings yet

- Vegetarianism Ecofeminism Kheel PDFDocument15 pagesVegetarianism Ecofeminism Kheel PDFJorge Sierra MerchánNo ratings yet

- Bennet VibrantMatter FoodDocument13 pagesBennet VibrantMatter Foodsara_23896No ratings yet

- Henninger-Rener+in+Brown 2020 Perspectives An+introduction+to+cultural+anthropologyDocument19 pagesHenninger-Rener+in+Brown 2020 Perspectives An+introduction+to+cultural+anthropologyMonice Van WykNo ratings yet

- Class 7 - Maslow 1954Document23 pagesClass 7 - Maslow 1954utari2210No ratings yet

- Healthy Food EssaysDocument4 pagesHealthy Food Essaysafabjgbtk100% (2)

- Goan CuisineDocument18 pagesGoan CuisineChetanya MundachaliNo ratings yet

- Culinary Triangle and The Living Foods DietDocument8 pagesCulinary Triangle and The Living Foods Dietfred400fNo ratings yet

- Gut Feeling: Twitter ShareDocument2 pagesGut Feeling: Twitter Shareprincess sanaNo ratings yet

- 44 Kheel Vegetarianism-EcofeminismDocument15 pages44 Kheel Vegetarianism-EcofeminismPonyo LilpondNo ratings yet

- Notas Comida PrisiónDocument4 pagesNotas Comida PrisiónIvan PojomovskyNo ratings yet

- 1916 Cocroft What To Eat and WhenDocument389 pages1916 Cocroft What To Eat and Whenmike bgkhhNo ratings yet

- Ethnocentrism and Cultural RelativismDocument19 pagesEthnocentrism and Cultural RelativismJeff LacasandileNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Food TaboosDocument4 pagesThesis On Food Taboosbk1hxs86100% (1)

- SynopsisDocument12 pagesSynopsisTalina Binondo100% (1)

- Breatharianism Science ofDocument16 pagesBreatharianism Science ofJoe CoulingNo ratings yet

- Argumentative EssayDocument6 pagesArgumentative Essayapi-2062309880% (1)

- Gut Crisis: How Diet, Probiotics, and Friendly Bacteria Help You Lose Weight and Heal Your Body and MindFrom EverandGut Crisis: How Diet, Probiotics, and Friendly Bacteria Help You Lose Weight and Heal Your Body and MindNo ratings yet

- Ecstatic States Result More From Sociocultural and Political Causes Than From Psychological and Physiological CausesDocument5 pagesEcstatic States Result More From Sociocultural and Political Causes Than From Psychological and Physiological Causesadi_6294No ratings yet

- Intestinal Ills: Chronic Constipation, Indigestion, Autogenetic Poisons, Diarrhea, Piles, Etc. Also Auto-Infection, Auto-Intoxication, Anemia, Emaciation, Etc. Due to Proctitis and ColitisFrom EverandIntestinal Ills: Chronic Constipation, Indigestion, Autogenetic Poisons, Diarrhea, Piles, Etc. Also Auto-Infection, Auto-Intoxication, Anemia, Emaciation, Etc. Due to Proctitis and ColitisNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2Document24 pagesLesson 2Margaret MoseleyNo ratings yet

- AirVeda: Ancient & New Medical Wisdom, Digestion & Gas, Volume OneFrom EverandAirVeda: Ancient & New Medical Wisdom, Digestion & Gas, Volume OneNo ratings yet

- Research Based Argument 1Document8 pagesResearch Based Argument 1api-458357311No ratings yet

- Feeding An Identity - Gender, Food, and SurvivalDocument8 pagesFeeding An Identity - Gender, Food, and SurvivalRohini SharmaNo ratings yet

- Holy Food: How Cults, Communes, and Religious Movements Influenced What We Eat — An American HistoryFrom EverandHoly Food: How Cults, Communes, and Religious Movements Influenced What We Eat — An American HistoryNo ratings yet

- DR Raymond Bernard, GeriatricsDocument6 pagesDR Raymond Bernard, GeriatricsMeșterul ManoleNo ratings yet

- Neo Malthusian EssayDocument2 pagesNeo Malthusian EssayNicholas Wezley Bahadoorsingh100% (10)

- Proceedings The Nutrition Society: by MurcottDocument8 pagesProceedings The Nutrition Society: by MurcottkonstantinosntellasNo ratings yet

- Understanding PerpetuaDocument16 pagesUnderstanding PerpetuaAdam RiceNo ratings yet

- Shelton, Herbert - OrthotrophyDocument476 pagesShelton, Herbert - OrthotrophyAlexandru Cristian StanciuNo ratings yet

- The Vegan MythDONEDocument3 pagesThe Vegan MythDONETri shaNo ratings yet

- Art and Brain: OriginalDocument5 pagesArt and Brain: OriginalAdina OlteanuNo ratings yet

- Is Religion Adaptive? Yes, No, Neutral, But Mostly We Don't KnowDocument16 pagesIs Religion Adaptive? Yes, No, Neutral, But Mostly We Don't KnowNatasha DemicNo ratings yet

- How We Eat: Appetite, Culture, and the Psychology of FoodFrom EverandHow We Eat: Appetite, Culture, and the Psychology of FoodRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Cultural Aspects of Meals and Meal FrequencyDocument8 pagesCultural Aspects of Meals and Meal Frequencyaleksandra.gozdurjpjoNo ratings yet

- Do We Control Our BodyDocument4 pagesDo We Control Our BodyHussieny ShaabanNo ratings yet

- Food Culture in ChinaDocument20 pagesFood Culture in ChinaMaria FrolovaNo ratings yet

- Natural Hygiene MagazineDocument33 pagesNatural Hygiene MagazineColm Rooney100% (1)

- Exploring The TabooDocument2 pagesExploring The TabooAracely Samira Curo TevesNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Eating Disorders in The Jewish World: LandsmanDocument2 pagesAn Analysis of Eating Disorders in The Jewish World: Landsmanoutdash2No ratings yet

- Note 2Document1 pageNote 2XinyiNo ratings yet

- Note 4Document1 pageNote 4XinyiNo ratings yet

- NOTE1Document1 pageNOTE1XinyiNo ratings yet

- Note 4Document1 pageNote 4XinyiNo ratings yet

- Note 2Document1 pageNote 2XinyiNo ratings yet

- Note 3Document2 pagesNote 3XinyiNo ratings yet

- Note 4Document2 pagesNote 4XinyiNo ratings yet

- Note 2Document3 pagesNote 2XinyiNo ratings yet

- Note 3Document3 pagesNote 3XinyiNo ratings yet

- NOTE5Document2 pagesNOTE5XinyiNo ratings yet

- Note 3Document2 pagesNote 3XinyiNo ratings yet

- Note 3Document1 pageNote 3XinyiNo ratings yet

- Note 4Document1 pageNote 4XinyiNo ratings yet

- JRN113新闻写作笔记Document1 pageJRN113新闻写作笔记XinyiNo ratings yet

- NOTE1Document2 pagesNOTE1XinyiNo ratings yet

- NOTE1Document1 pageNOTE1XinyiNo ratings yet

- Note 2Document1 pageNote 2XinyiNo ratings yet

- Coumpound Words (Grade4)Document13 pagesCoumpound Words (Grade4)Mai Mai BallanoNo ratings yet

- TOEFL Reading Practice Paper 18Document7 pagesTOEFL Reading Practice Paper 18Lindsay HajinNo ratings yet

- MAPV212 Chap 2 Worksheet 1-2-3Document3 pagesMAPV212 Chap 2 Worksheet 1-2-3Michael JohnNo ratings yet

- Cream Black Cat Full Sleeves Shirt Style Clothe StoreDocument1 pageCream Black Cat Full Sleeves Shirt Style Clothe StorebaazzithNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Impact On Performance in Student-Athletes - Reality AnDocument36 pagesNutritional Impact On Performance in Student-Athletes - Reality AnAbbygail WasilNo ratings yet

- Copy PresentationDocument37 pagesCopy PresentationTanishq KatariaNo ratings yet

- Expansion Joint ManualDocument26 pagesExpansion Joint ManualOdo AsuNo ratings yet

- Sales ContactDocument2 pagesSales ContacthanumsaavNo ratings yet

- Hepatoprotective Activity of Siddha Medicinal IndigoferaDocument4 pagesHepatoprotective Activity of Siddha Medicinal IndigoferaugoNo ratings yet

- Delhi CompDocument10 pagesDelhi CompPatrick AdamsNo ratings yet

- شعر حسب د.باسلDocument15 pagesشعر حسب د.باسلعبدالرحمن كريمNo ratings yet

- Image Feature ExtractionDocument11 pagesImage Feature Extractionabdullah saifNo ratings yet

- Supplementary Information: Appendix 1: Answers To End-of-Chapter Material - 680 Glossary - 696 Index - 717Document47 pagesSupplementary Information: Appendix 1: Answers To End-of-Chapter Material - 680 Glossary - 696 Index - 717Humberto A. HamaNo ratings yet

- 2008 Synapigl 5Document6 pages2008 Synapigl 5ahson23No ratings yet

- Safari - 21Document1 pageSafari - 21bernardNo ratings yet

- Take Off Magazine 07 July 2012Document49 pagesTake Off Magazine 07 July 2012Luptonga100% (2)

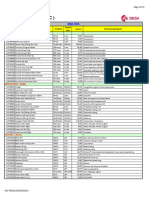

- Price List (2 Feb'24) HEC-P0005-2024Document13 pagesPrice List (2 Feb'24) HEC-P0005-2024stts motorNo ratings yet

- Forsspac Due DiligenceDocument5 pagesForsspac Due Diligencebhavin24uNo ratings yet

- Alligation QuestionDocument5 pagesAlligation QuestionSahil GuptaNo ratings yet

- The Psychological Aspect of A Muslim's Slave MentalityDocument7 pagesThe Psychological Aspect of A Muslim's Slave MentalitySujit DasNo ratings yet

- Sag Tension CalculationsDocument9 pagesSag Tension CalculationsPrayas SubediNo ratings yet

- Hp200rg SsDocument2 pagesHp200rg SsJad IssaNo ratings yet

- Puddle Flange Thickness Sheet-P2m-R0Document1 pagePuddle Flange Thickness Sheet-P2m-R0Faisal MumtazNo ratings yet

- Crane Spec Book 2015Document42 pagesCrane Spec Book 2015Ahmad SujaiNo ratings yet

- Ims - 004 Gen Ppe Request FormDocument1 pageIms - 004 Gen Ppe Request FormJohn KalvinNo ratings yet

- Olahraga & Outdoor SHOPEEDocument193 pagesOlahraga & Outdoor SHOPEEAtun SopiNo ratings yet

- Down SyndromeDocument5 pagesDown SyndromeSheena CabrilesNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Constituents in Jamaica Quassia Extract, A Natural Bittering AgentDocument4 pagesAnalysis of Constituents in Jamaica Quassia Extract, A Natural Bittering AgentwisievekNo ratings yet

- Am-6082ーsolicitud de Cotizacion 555 (07!09!2023)Document2 pagesAm-6082ーsolicitud de Cotizacion 555 (07!09!2023)Diego LópezNo ratings yet

- Your Best FriendDocument174 pagesYour Best FriendChandan RitvikNo ratings yet