Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1958 Jacob Mincer - Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution

Uploaded by

Cynthia CamposOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1958 Jacob Mincer - Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution

Uploaded by

Cynthia CamposCopyright:

Available Formats

Investment in Human Capital and Personal Income Distribution

Author(s): Jacob Mincer

Source: Journal of Political Economy , Aug., 1958, Vol. 66, No. 4 (Aug., 1958), pp. 281-

302

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.com/stable/1827422

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to Journal of Political Economy

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

THE JOURNAL OF

POLITICAL ECONOMY

Volume LXVI AUGUST 1958 Number 4

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL AND PERSONAL

INCOME DISTRIBUTION

JACOB MINCER

City College of New York

I. INTRODUCTION Since income inequality is observable

in terms of the shapes or parameters of

ECONOMISTS have long theorized

statistical frequency distributions, theo-

about the nature or causes of in-

ries of the determinants of personal in-

equality in personal incomes. In

come distribution, if they are to be

contrast, the vigorous development of

operational, must predict features of the

empirical research in the field of personal

observable statistical constructs.

income distribution is of recent origin.

Probably the oldest theory of this

Moreover, the emphasis of contempo-

type is the one that relates the distribu-

rary research has been almost completely

tion of income to the distribution of

shifted from the study of the causes of

individual abilities.2 A special form of

inequality to the study of the facts and

this theory can be attributed to Galton,

of their consequences for various aspects

who claimed that "natural abilities" fol-

of economic activity, particularly con-

low the Gaussian normal law of error.

sumer behavior.

This, it appeared to Galton, was a simple

However, the facts of income inequal-

ity do not speak for themselves in sta-

consequence of Quetelet's findings that

various proportions of the human body

tistical frequency distributions. The facts

are normally distributed. A seemingly

must be recognized in the statistical con-

natural corollary of this logic was the hy-

structs and interpreted from them. Per-

haps the most important conclusion to 1 This is brought out in the distinction between

the "permanent" and the "transitory" components

be drawn from research into the influ-

of income as applied to the analysis of consumption

ence of income distribution on consump- in Milton Friedman, A Theory of the Consumption

tion is that the effects of inequality de- Function (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University

Press, 1957).

pend upon its causes.' Thus factors as-

sociated with observed inequality must 2 A more detailed review of these theories can be

found in H. Staehle, "Ability, Wages, and Income,"

be taken into account before the data Review of Economics and Statistics, XXV (February,

can be put to any use. 1943), 77-87.

281

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

282 JACOB MINCER

pothesis of a normal distribution of in- intervene to distort the relation between

comes. Although the invention of intelli- ability and income. Thus, given a defini-

gence quotients appeared to confirm con- tion of the former independent of income,

clusions derived by a non sequitur, the the relation between the two can be dis-

hypothesis of a normal distribution of in- cerned only in subgroups homogeneous

comes was definitively shattered by with respect to all other factors. Ability

Pareto's famous empirical "law" of in- is relegated to a residual role, and the

comes. emphasis is shifted to other factors.

For a long time this refutation of a Pigou pointed to the distribution of

logically weak hypothesis was considered property as the most important of the

to present a strange puzzle. Pigou termed other factors. This position resolves the

it a paradox :' How can one reconcile the paradox, but it is not a theory of income

normal distribution of abilities with a distribution until the other factors are

sharply skewed distribution of incomes? built into models with predictive proper-

This became the central question around ties.

which thinking on the subject subse- Curiously enough, the one factor con-

quently revolved. sistently selected for such constructive

One answer, of comparatively recent purposes in the recent literature is

origin, is that the abilities relevant to "chance," a concept as difficult to define

earning power should not be identified as "ability." The earliest and basic ver-

with I.Q.'s. Indeed, relevant abilities sion of the stochastic models is that of

are likely not to be normally distributed, Gibrat.5 Its logical construction is as fol-

as I.Q.'s are, but to be distributed in a lows: Start with some distribution of in-

way resembling the distribution of in- come, with mean Mo and variance Vo,

come.4 This amounts to saying that in- and let individual incomes be subjected

come distributions should not be de- to a random increase or decrease over

duced from psychological data on dis- time as a result of "chance" or "luck."

tributions of abilities but, conversely, Let the variance of the annual changes in

that the latter, which are not observable, income in year t be Vt, and let those

should be inferred from the former, changes be uncorrelated with the levels

which are. This reversal of independent of income on which they impinge. Then

and dependent variables may be of the variance of the income distribution

interest to psychologists, but income at time (t + n) will be

analysts are not left with much more n

than a tautology. Vn = VO+ E Vt.

t=1l

A more general and traditional answer,

given by Pigou himself, is that income- With n increasing without bounds, any

determining factors other than ability Vt becomes very small in comparison

3 A. C. Pigou, The Economics of Welfare (London: with 2tvt, and similarly VO becomes small

Macmillan & Co., Ltd., 1932), p. 648. in comparison with Vn. Under these

4 C. Burt, "Ability and Income," British Jour- conditions, probability theory guaran-

nal of Educational Psychology, XIII (June, 1943),

95 ff.; A. D. Roy, "The Distribution of Earnings and

tees that in time the distribution of

of Individual Output," Economic Journal, LX income will approach normality, regard-

(September, 1950), 489-505. For the origin of the less of the form of the initial distribution.

hypothesis see C. H. Boissevain, "Distribution of

Abilities Depending on Two or More Independent R. Gibrat, Les Inggalitgs gconomiques (Paris:

Factors," Metron, XIII (December, 1939), 49-58. Sirey, 1931).

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL 283

Personal income distributions are not come variance increases with time for

normally or symmetrically distributed, each age cohort but, given a stable popu-

but the distribution of logarithms of in- lation, the aggregate variance remains

come is rather symmetric and in a rough unchanged.

way approximates normality. The proc- Unless we assign specific interpreta-

ess of "random shock" just described tions to the "chance" factor, it is difficult

generates a log-normal distribution if ap- to see how the stochastic models increase

plied to the logarithms of income rather our understanding of the processes un-

than to income itself. Thus the proper derlying the formation of personal in-

assumption to be made is that the ran- come distributions. If the "chance" fac-

dom shock consists of relative or per- tor is to be understood as a net effect of

centage, rather than absolute, income all kinds of causes, this approach is an

changes, which are independent of in- admission of defeat in the efforts to gain

come levels. This is Gibrat's "law of insight into systematic factors affecting

proportionate effect." the distribution of income. Moreover, the

Kalecki has pointed out a serious de- operational scope of the stochastic models

fect in Gibrat's approach.6 The model has not kept pace with the increasing

implies that, as time goes by, aggregate empirical knowledge about the multi-

income inequality increases because each dimensional structure of the personal

subsequent random shock adds a term income distribution. With few excep-

to the sum on the right side of the ex- tions,9 the sole purpose of the models is

pression

to rationalize a presumed mathematical

n

form of the aggregate.

Vn= V0+ E Vt.

t=l

From the economist's point of view,

perhaps the most unsatisfactory feature

This, however, is empirically false. of the stochastic models, which they

Subsequent models correct this defect share with most other models of personal

in either of two ways. One is to postulate income distribution, is that they shed no

a negative correlation between the size light on the economics of the distribu-

of the random shock and the level of in- tion process. Non-economic factors un-

come, to be interpreted as a decreasing

doubtedly play an important role in the

likelihood of large negative changes with

distribution of incomes. Yet, unless one

a decreasing level of income.7 This re-

denies the relevance of rational optimiz-

striction assures constancy of the vari-

ing behavior to economic activity in

ance of the distribution. Another way is

general, it is difficult to see how the

to apply the random shock, without re-

factor of individual choice can be disre-

striction, separately to age cohorts

throughout their life-histories.8 The in- garded in analyzing personal income

distribution, which can scarcely be inde-

6 M. Kalecki, "On the Gibrat Distribution," pendent of economic activity.

Econometrica, XIII (April, 1945), 161-70.

The starting point of an economic

7 Ibid.; see also D. G. Champernowne, "A Model

of Income Distribution," Economic Journal, LXIII analysis of personal income distribution

(June, 1953), 318-51. must be an exploration of the implica-

8 R. S. G. Rutherford, "Income Distributions: A tions of the theory of rational choice. In

New Model," Econometrica, XVIII (July, 1955),

425-40. 9Ibid.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

284 JACOB MINCER

a recent article" Friedman has pointed that a year of training reduces earning

out two ways in which individual choice life by exactly one year.l2 If individuals

can affect the personal income distribu- with different amounts of training are to

tion. One, around which Friedman built be compensated for the costs of training,

his model, is related to differences in the present values of life-earnings must

tastes for risk and hence to choices be equalized at the time a choice of occu-

among alternatives differing in the prob- pation is made. If we add a provisional

ability distribution of income they prom- assumption that the flow of income

ise. Friedman has shown that such a receipts is steady during the working life,

model is, no less than the others, capable it is possible to estimate the extent of

of reproducing the more outstanding compensatory income differences due to

features of the aggregative distribution differences in the cost of training.'3

of income. The other, and more familiar, The cost of training depends upon the

implication of rational choice is the length of the training period in two ways.

formation of income differences that are First and foremost is the deferral of

required to compensate for various ad- earnings for the period of training;

vantages and disadvantages attached to second is the cost of educational services

the receipt of the incomes. This prin- and equipment, such as tuition and

ciple, so eloquently stated by Adam books, but not living expenses.

Smith, has become a "commonplace of For simplicity, consider the case in

economics. "I' which expenses for educational services

XWhat follows is an attempt to cast are zero. Let

one important aspect of this compensa- I = length of working life plus length of

tion principle into an operational model training, for all persons = length of

working life of persons without training,

that provides insights into some features

of the aggregative personal income dis- 12 According to a recent study, the average length

of working life in eight broad occupational groups is

tribution and into a number of decom- as follows:

positions of it which recent empirical re- Mean No.

Years in

search has made accessible. The aspect Occupation Labor Force

Professional and technical workers.... 40

chosen concerns differences in training Managers and officials .............. 41

Craftsmen and foremen ............. 44

among members of the labor force. Operatives and kindred workers ...... 45

Clerical and sales workers ........... 47

Non-farm laborers ......... ........ 51

Service workers .................... 52

II. A SIMPLE MODEL

Similar patterns were observed in 1930,

Assume that all individuals have 1950. Commenting on the findings, the

identical abilities and equal opportuni- the study observe: "In general men spend, on the

average, fewer years in what may be termed the

ties to enter any occupation. Occupations better jobs. The three occupations with the shortest

differ, however, in the amount of train- working life are those in which greater training,

education and experience are required. These are

ing they require. Training takes time,

also the jobs which in general afford larger earnings.

and each additional year of it postpones Clearly the men in the better jobs-as measured by

the individual's earnings for another earnings and education-spend a shorter period of

their lives in the working force" (A. J. Jaffe and

year, generally reducing the span of his

R. 0. Carleton, Occupational Mobility in the United

earning life. For convenience, assume States, 1930-1960 [New York: King's Crown Press,

1954], p. 50).

10 M. Friedman, "Choice, Chance, and the Per- 13 With minor exceptions, the procedure is

sonal Distribution of Income," Journal of Political basically a generalization of the one used by Fried-

Economy, LXI (August, 1953), 277-90. man and Kuznets in Income from Independent Pro-

11 Thus termed by J. R. Hicks in The Theory of fessional Practice (New York: National Bureau of

Wages (New York: P. Smith Co., 1941), p. 3. Economic Research, 1945), pp. 142-51.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL 285

an= annual earnings of individuals with n Less obvious is the finding that kn, n-d is

years of training,

a positive function of n (d fixed); that is,

Un = the present value of their life-earnings at

start of training,

the relative income differences between,

r = the rate at which future earnings are for example, persons with 10 years and

discounted, 8 years of training are larger than those

t = 0, 1, 2, . .. , I-time, in years, between individuals with 4 and 2 years

d = difference in the amount of training, in of training, respectively. Hence the ratio

years, and

of annual earnings of persons differing

e = base of natural logarithms.

by a fixed amount of schooling (d) is at

Then least as great as

kd, v

0=XrlI 1

er(1-d) -

Vn = a,

the ratio of earnings of persons with d

when the discounting process is discrete.

years of training to those of persons with

And, more conveniently, when the

no training. However, since the change

process is continuous,

in ki, n-d with a change in n is neg-

Vn = an (e-rt) dt = - ( e-rn - e-rl) ligible,14 it can be, for all practical pur-

r

poses, treated as a constant k.

Similarly, the present value of life- This result can be summarized in the

earnings of individuals with (n - d) following statement: Annual earnings

years of training is corresponding to various levels of train-

a~n-d ing differing by the same amount (d)

Vn-d = a- ( e-r(n-d) - e-rl) differ, not by an additive constant, but

r

by a multiplicative factor (k).

The ratio, kn, n-dy of annual earnings of

This important conclusion remains

persons differing by d years of training is

basically unchanged when, in addition to

found by equating Vn Vn= d:

the cost of income postponement, ex-

an e-r(n-d) - e-rl penses of training are taken into account.

Enn-d = = -

an, n dde-r - e-rl The additional cost element naturally

er(l+d-n) - 1

widens the compensatory differences in

er(1-n) 1

earnings particularly at the upper edu-

It is easily seen that kn, n-d is (a) cational levels, where such costs are

larger than unity, (b) a positive function sizable.15

of r, and (c) a negative function of 1. In 14 Assuming the values of r and I to be in a rather

other words, as would be expected, (a) wide neighborhood of 0.04 and 50, respectively.

15 The percentage increase in relative income

people with more training command

differences between persons with (n) and (n - d)

higher annual pay; (b) the difference be- years of training resulting from the introduction of

tween earnings of persons differing by d schooling expenses can be measured by the ratio of

years of training is larger, the higher the annual schooling expenses to annual earnings in

groups with (n - d) years of training.

rate at which future income is dis- For example, if average earnings of high-school

counted, that is, the greater the sacrifice graduates are $4,000 and the annual expenses of a

involved in the act of income postpone- college education are $1,000, then to the compensa-

tory income differences due to the deferral of in-

ment; (c) the difference is larger, the come for 4 years (k4 -1) we must add (1,000/4,000)

shorter the general span of working life, (k4 - 1) to compensate for the cost of tuition. This

since the costs of training must be re- increases the differences by 25 per cent (see my un-

published Ph.D. dissertation, "A Study of Personal

couped over a relatively shorter period. Income Distribution" [Columbia University, 19571.

These conclusions are quite obvious. chap. ii, Note 2).

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

286 JACOB MINCER

It is, of course, the purpose of the the factor k increases somewhat with the

model to make the distribution of annual level of training, so that even the loga-

earnings a sole function of the distribu- rithms of income would be slightly

tion of training among members of the skewed.

labor force. It follows from what we have Formally, the existence of positive

just shown that this function is of a very skewness introduced by compensatory

simple form: given the distribution of income differences due to differences in

training, the multiplicative constant k training can be shown, and its extent can

serves as a "conversion factor" which be estimated, in a rather simple way.

translates it into a distribution of earn- Let the quartile deviation in the sym-

ings. In order, therefore, to make state- metric distribution of training be d

ments about the theoretical distribution years, and let Y be the first quartile

of earnings, we must first consider the income, Q1. It follows from the previous

distribution of training within the uni- argument that the median, Q2, equals

verse of this model. Y times kd and the third quartile, Q3,

Under the most stringent assumptions equals Y times k2d.

of identical abilities and equal access to Hence Bowley's measure of skewness16

training, the distribution of occupational is

choice, defined as choice of particular

Sk- _(Q3-Q2)-(Q2-Q1) kd2d-2 kd+ 1

lengths of training, would become a

Q3 -Q1 k2d-1

matter of tastes, specifically those con-

cerning the different activities in the dif- (k E- 1 ) 2 kd - 1

= = - o O

ferent occupations and time preferences. k2d- 1 kd + 1

It is not clear what form the distribution

Since k is greater than 1, Sk must be

of training would assume in this con- positive.

jectural state of affairs, even with the

If we now relax the assumption of

usual assumption of a symmetric, or identical abilities, a positive correlation

normal, distribution of tastes.

between the amount of training and some

Suppose, for the sake of argument, ability traits is plausible. Given freedom

that the resulting distribution of training

of choice, persons with greater learning

is symmetric. The point which this

capacity are more likely than others to

model brings home is that, even in that

embark on prolonged training. Insofar as

case, the annual distribution of earnings

earnings are positively related to such

will depart from symmetry in the direc-

qualities, aggregative skewness is aug-

tion of positive skewness. mented.

As we have seen, the annual earnings

But whether or not the distribution

corresponding to various levels of train-

of training depends on distributions of

ing differing by the same length of time

abilities,17 the mere existence of dis-

differ by a multiplicative factor k. Were

this factor constant for all levels of train- 16 By the same procedure, a simple measure of

ing, a normal distribution of absolute relative dispersion is

time differences in training would reflect Q3-Q1 k2d- 1 1

_ = __= - _

itself in a normal distribution of per- Q2 kd ad

centage differences in annual earnings, 17 Differences in abilities introduce additional

that is, in the familiar, positively skewed dispersion into the income distribution. In particu-

lar, any degree of positive correlation between

logarithmic-normal income distribution.

ability and differences in training magnifies the

Strictly speaking, the model implies that extent of "interoccupational" income differences.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL 287

persion in the amount of tivetraining

performance andimplies

hence a decline in

that aggregative skewness is greater than earnings, particularly in jobs where

it would be in its absence. In particular, physical effort or motor skill is involved.

even if it were true that abilities are dis- Thus, in general, the "life-cycle" of

tributed in a way which, ceteris paribus, earnings exhibits an inverted U-shaped

implies a symmetric distribution of earn- pattern of growth and decline typical of

ings, positive skewness would appear in many other growth curves.

that distribution as soon as choice of We have already seen that differences

training was admitted into the model. in formal training result in compensatory

Thus Pigou's paradox would persist even differences in levels of earnings as be-

in the absence of the institutional fac- tween different "occupations," the latter

tors that he invoked to explain it. defined in terms of length of formal train-

ing. This compensatory principle must,

EXTENSION OF THE MODEL

of course, also remain valid when life-

Primarily for mathematical conven- paths of earnings are sloped. An im-

ience, I have expressed differences in portant new question arises: What

training in terms of definite time periods specific assumption is to be made about

spent on formal schooling. However, the differences between these slopes in the

process of learning a trade or profession different occupations, since these in turn

does not end with the completion of imply differences in the dispersion of

school. Experience on the job is often the earnings within the occupational groups?

most essential part of the learning Casual observation suggests that pat-

process. terns of age-changes in productive per-

Just as formal training can be meas- formance differ among occupations as

ured by the length of time spent at well as among individuals. The explora-

school, the other part of the training tion of such differences is a well-estab-

process-experience-can be introduced lished subject of study in developmental

into the theoretical model in terms of psychology.

the A survey of broad, rather

amount of time spent on the job. When tentative findings in this field indicates

this is done, "intra-occupational" pat- that (a) growth in productive perform-

terns of income variation, previously ance is more pronounced and prolonged

abstracted from, must emerge. By defi- in jobs of higher levels of skill and com-

nition, the amount of formal training is plexity; (b) growth is less pronounced

the same for each member of an occupa- and decline sets in earlier in manual

tion. However, the productive efficiency work than in other pursuits; and (c) the

or quality of performance on the job is a more capable and the more educated

function of formal training plus experi- individuals tend to grow faster and

ence, both measured in time units; hence longer than others in the performance of

it is a function of age. We are thus forced the same task.'8

to relax another assumption, previously These findings suggest that experience

adopted for convenience, namely, that influences productivity more strongly in

earnings are of the same size in each jobs that normally require more training.

period of an individual's earning life. The steeper growth of performance

Clearly, as more skill and experience throughout the span of working life in

are acquired with passage of time, earn-

occupations with higher levels of train-

ings rise. In later years aging often

brings about a deterioration of produc- 18 See Mincer, op. cit., chap. ii, Note 1.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

288 JACOB MINCER

ing implies that Observe,

the however,

growth of

that such a phe- ear

also greater. nomenon is in part ruled out by our

These considerations point to the re- previous assumptions. Membership in an

placement of the previous assumption of occupational group was defined by the

horizontal life-paths of earnings with the number of years of the individual's

assumption that the slopes of time-paths formal training, which is determined

of earnings vary directly with the once for all by the calculus of occupa-

amount of formal training, that is, with tional choice (the equalization of present

"occupational rank." values) before entry into the labor force.

In other words, if we define "vertical oc-

IMPLICATIONS

cupational mobility" as the movement

In brief, we are led to the following from a group with, say, n - d years of

conclusion: Differences in training result training to a group with n years of train-

in differences in levels of earnings among ing, this is, by definition, impossible

''occupations" as well as in differences in after the training period is over. If, in

slopes of life-paths of earnings among oc- addition, secular occupational shifts are

cupations. The differences are system- abstracted from, occupational distribu-

atic: the higher the "occupational rank," tion must be alike in all age groups after

the higher the level of earnings and the all training periods are over; a fortiori,

steeper the life-path of earnings. age distributions must be alike in all oc-

Two implications of basic importance cupational groups.'9 With this qualifica-

for empirical investigation follow im- tion, the direct translation of slopes of

mediately from these findings. life-paths of earnings into patterns of

1. Since, under our assumptions, intra- income dispersion is achieved: dispersion

occupational differentials are a function must increase with "occupational rank."

of age only, the statement that life- 2. Now consider income recipients

paths of earnings are steeper for the classified into separate age groups. In

more highly trained groups of workers our model, income differences within

means that income differences between each age group are due to differences in

any two members of such a group differ- the occupational characteristics of its

ing in age are greater than income differ-

ences between their contemporaries in an 19 Actually, the assumptions need not be so

rigid, as a certain amount of dissimilarity in age dis-

occupational group requiring less train-

tributions will not affect the systematic effects of

ing. differences in the steepness of life-paths on intra-

In itself, this conclusion does not group dispersion. Indeed, 1950 Census data indicate

that the dissimilarity is rather small among broad

necessarily imply a systematic differ- occupational groups when comparisons are re-

ence in income dispersion within the two stricted to the ages between 25 and 65:

groups. It points to age distributions PERCENTAGE DISTRIBUTION OF AGES BY OCCU-

PATION, U.S. MALE WAGE AND

within the respective groups as another SALARY EARNERS, 1950*

factor that must be considered. Clearly, AGE GROUPS

if one group consists of members with OCCUPATION 25-35 35-45 45-55 55-65 TOTAL

Professional and

very similar ages and in another there is managerial ..... 30.6 31.1 23.8 14.5 100.0

Clerical and sales. 35.8 28.0 21.8 14.4 100.0

a wide range of ages, there may be less Craftsmen and

foremen ....... 29.9 30.0 24.1 16.0 100.0

income dispersion in the first group, evenOperatives and

service. 33.8 29.8 21.6 14.8 100.0

though its life-path of earnings may be Non-farm laborers. 32.4 28.2 22. 7 16.7 100.0

* Source: Occupational Characteristics (Census Special

steeper than that of the second group. Rept. P-E, No. 1B), Table 5, pp. 53-59.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL 289

members. The income differences cor- For convenience, divide the labor force

responding to those occupational cate- into two broad groups of "occupations,"

gories, however, increase with age. Life- those requiring very little training, char-

patterns of earnings are not parallel; acterized by a practically flat life-pattern

their divergence becomes more pro- of earnings (ABU in Fig. 1), and those

nounced with added years of experience, requiring a considerable amount of train-

so that income dispersion increases as we ing, with a pronounced positive slope of

move from younger to older age groups. life path (CBT in Fig. 1). First, we may

Annual

Earnings

H __ __ __ _

O~~~~~~~~~L /

FIG. 1.-Hypothetical life-paths of earnings in occupations differing in the amount of training they

require.

Both statements can be made stronger note that absolute differences in earnings

by specifying that they apply not only are small within untrained groups (life-

to absolute but also to relative disper- path A B U), but they become pro-

sion. The former follows directly from nounced in groups with higher levels of

the model. If we now include in the as- training (CBT). These differences (abso-

sumption about the slopes of life-paths lute dispersion) may be measured by the

of earnings in various "occupations" the slopes of the paths or by the segments

observation that these slopes are neg- UL and TL, respectively. Income levels

ligible or even negative in occupations are represented by the heights US and

requiring little or no formal training, as TS, respectively. Clearly UL/US <

in many manual jobs, then the two TL/TS. That is, relative dispersion in-

propositions must also apply to relative creases with "occupational rank. " Second,

dispersion. the ratio TS/US increases with age:

The argument underlying these propo- TSjUS > T'S'/U'S'. That is, percent-

sitions can be presented quite simply age differences and hence the relative dis-

with the help of a geometric illustration. persion of earnings increase as we move

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

290 JACOB MINCER

from a younger to an older "occupation- marily with respect to level and dis-

mix." persion.""2 He found that there is con-

We may now return to the aggregative siderably more symmetry in component

income distribution and explore the im- income distributions than in the aggre-

plications for the total of the hypothesis gate. For example, the distributions for

about patterns of income in component sets of the three broad occupational

groups. groups of employed males, "blue-collar

First, it is obvious that the addition of workers," "white-collar workers," and

"intra-occupational" differences to the professionals, managers, and proprietors,

"interoccupational" differences increases had less skewness when considered sepa-

aggregate inequality. Moreover, "inter- rately than in the aggregate.

occupational" differences themselves Pigou's hunch about the anatomy of

must increase: The present value of a personal income distributions, even when

life-flow of income of given size is smaller, confirmed by Miller's empirical investi-

the steeper the positive slope of the age- gations, however, cannot explain the

income relation. Hence the equalization phenomenon of aggregative positive

of present values requires larger "inter- skewness. It leaves unanswered the basic

occupational" differences in income than question why a merger of relatively

those derived on the assumption of symmetric distributions should result in a

horizontal income flows in all "occupa- positively skewed aggregate. Clearly,

tions." without further specifications, a merger

Finally, it can be shown that the con- of component symmetric distributions

clusions about "intra-occupational" pat- could very well produce a negatively

terns of income dispersion reinforce the skewed or a symmetric aggregate.

implication of aggregative positive skew- My model provides specifications

ness reached on the basis of "interoccu- which insure that a merger produces

pational" differences alone (in the simple positive skewness in the aggregate. The

model) This finding provides an answer aggregative skewness was already im-

to an important question frequently plied by the simple model. In that form,

raised in discussions of personal income however, income dispersion within occu-

distribution. pations was implicitly assumed to be

Before invoking the distribution of zero. But if its existence is admitted, pat-

property as a decisive explanation of terns of "intra-occupational" dispersion

positive income skewness, Pigou con- might easily affect the aggregative, posi-

sidered the possibility that positive tive skewness previously derived. This

skewness of the income distribution may would be the case, for example, if dis-

arise from merging of a number of persion within less trained groups were

homogeneous, non-skewed subgroups systematically and considerably greater

into a non-homogeneous, positively than that within more highly trained

skewed total.20 Recently, H. P. Miller groups. Geometrically, this would mean

has offered evidence to suggest that "the shortening the right tail of the aggrega-

skewness of income distributions is 21 H. P. Miller, "Elements of Symmetry in the

largely due to merging several symmet- Skewed Income Curve," Journal of the American

Statistical Association (March, 1955), pp. 55-71.

rical distributions which differ pri-

22 For a formal statement and discussion of the

20 Pigou, op. cit., p. 246. Other writers have fol-necessary and sufficient conditions for positive

lowed Pigou along these lines. skewness see Mincer, op. cit., chap. ii, Note 4.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL 291

tive income distribution and extending is, however, not so serious as it would

the left tail-a change in the direction of seem. Abstraction from secular trends in

negative skewness. However, this con- income imparts a downward bias to the

tingency is ruled out by my findings slopes of life-paths of income. On the

about component groups. In fact, I have other hand, cyclical and seasonal forces

derived patterns of "intra-occupational" impinging on the economy are largely

dispersion that are exactly the opposite eliminated by the cross-sectional "life-

of those given in the preceding extreme path." In this respect, it fits the theo-

example. This positive relation between retical construct in which these disturb-

income levels and income dispersion in ances are removed by assumption. More-

component groups reinforces the effect of over, the relevant income expectations

intergroup ("interoccupational") skew- are likely to be shaped by the contempo-

ness to produce an even greater positive rary cross-sectional picture.

skewness in the aggregate. Another translation problem that

bears directly on the selection of data

THEORETICAL CONCEPTS AND THEIR

is presented by the concept of training.

EMPIRICAL COUNTERPARTS

It will be recalled that I have subdivided

Ultimately, it is the degree of conform- this concept into "formal training," de-

ity of empirical observations with the fined by the time spent primarily in

conclusions suggested by the model preparation for the job, and informal

that establishes its usefulness. We must training or experience on the job. Given

note, however, that properties of the in- the former, the latter is conveniently

come structure specified by the model measured by age. The identification of

do not in themselves constitute a "pre- experience with age should not create

diction" about the empirical income dis- much difficulty, since the existence of

tribution. The validity of such an inter- central tendencies is to be expected in the

pretation depends on the way in which timing of both training and entry into

theoretical concepts like training, in- the labor force.

come, and life-paths of income are trans- More difficulty arises in measuring

lated into empirically identifiable, meas- "formal training." Years of school com-

urable counterparts. pleted as reported by the census do not,

The translation is necessarily imper- unfortunately, include time spent in

fect, in the sense that an exact empirical vocational, trade, and business schools,

representation of theoretical concepts is not to speak of apprenticeships and vari-

seldom possible, available, or even desir- ous forms of on-the-job training pro-

able. For example, the relevant income grams.23 Moreover, the schooling classi-

differences in a given annual income dis- fication is of limited usefulness, since it is

tribution are those among individuals rarely cross-classified with other relevant

differing in age and not those due to the characteristics of the population.

aging of the same individuals. While the A meaningful, though not easily

theoretical concepts of training and quantifiable, indicator of "formal train-

compensation thus involve a longitudinal ing" is occupational status. We can

view of individual income, they must be think of the set of occupations among

brought to bear on cross-sectional data.

23 U.S. Census of Population 1950, Vol. II: Char-

The discrepancy between the dynamic acteristics of the Population, Part 1: U.S. Summary,

concept and the cross-sectional measure Introduction, pp. 44-46.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

292 JACOB MINCER

which the labor force is divided as con- cate rather clearly that earnings are not

stituting a hierarchy ranging from occu- only higher but also increase more

pations requiring little training up to rapidly with age (or decline more slowly

highly specialized occupations whose after the peak of earnings is reached) in

practice presupposes a great deal of in- the more highly trained groups than in

vestment in human capital. If we can the less trained ones. A statistical study

order occupational groups in such a of the 1939 and 1949 income data pro-

"vertical" way, we can use their ranks as vided by the decennial censuses of popula-

indexes of the amount of formal training. tion reveals that the income differential

Despite the shortcomings of the edu- between young men and those who have

cational classification and the difficulties reached the age of peak income is much

in occupational ranking, I have used greater for college graduates than for

both education and occupation to meas- men with less schooling.24 According to

ure the amount of formal training. the same study, similar differentials are

For defining units of income and in- found when racial groups or sex groups

come recipients, it is clear that earnings are viewed separately. They exist in in-

rather than total incomes and persons comes from all sources as well as in wage

rather than families correspond to the and salary earnings. The same differen-

theoretical concepts. It is also desirable tials persist in incomes of spending units

to restrict the income recipients to per- classified by the schooling of the head.25

sons between the ages of twenty-five When occupation, rather than educa-

and sixty-five years, so as to include all tion, is used as a classificatory principle,

training groups after most have entered the occupational groups must be ranked

the labor force and before a sizable num- with respect to the amount of training

ber have retired. Furthermore, in order they presuppose. With broad occupa-

to avoid variations in income introduced tional groups, the vertical ordering from

by variation in man-hours or weeks of unskilled to highly skilled groups as

work during the year-a factor about shown in census tabulations is reason-

which the model is silent-either earn- ably appropriate for our purposes. By

ings of full-year workers or hourly rates and large, skill is an end-product of

should be studied. training, and the occupational ranks

Unfortunately, data fulfilling all these roughly follow the levels of education

requirements are practically non-exist- and of earnings in the groups.

ent. I was forced, therefore, to use data The positive association between oc-

with varying definitions of income and cupational rank, level of earnings, and

income recipient. The extent to which the amount of age change in earnings

the measures deviate from the require- stands out very clearly in figures of earn-

ments must be kept in mind as possible ings of employed males in the United

sources of discrepancy between theory States.26 Similar differences in occupa-

and fact. tional life-paths of income can be found

LIFE-PATHS OF INCOME

24 H. P. Miller, Income of the American People

Available data on the variation of (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1955), pp. 65-68.

earnings and incomes by age within 25 Federal Reserve Bulletin, XLI (June, 1955),

broad population groups classified by 615, Supplementary Table 3.

educational and occupational status indi- 26 Miller, op. cit., Table 24, p. 54.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL 293

in a number of other sets of empirical tributions. Even on the aggregate level,

data.27 however, the model not only indicates

AGGREGATIVE SKEWNESS the existence of positive skewness but

enables us to gain a rough impression of

Ability to explain the existence of ag-

the quantitative importance of the set

gregate skewness is a preliminary test

of factors on which we have focused.

that any theory of personal income dis-

An estimate of the extent of aggrega-

tribution must meet. The usefulness of

tive skewness and dispersion which is

my approach does not end with meeting

ascribable to differences in training and

this test, which can be and has been met

experience was obtained in the following

in so many other ways. Its main merit

fashion.

lies in the guidance it provides for in-

Hypothetical coefficients of relative

terpreting disaggregations of income dis-

dispersion and skewness were calculated

27 See H. F. Lydall, "The Life Cycle in Income,

Saving, and Asset Ownership," Econometrica, April,

that would obtain if differences in earn-

1955, pp. 131-50; BLS Bulletin 643, p. 55; M. Leven, ings were exclusively of a compensatory

The Income Structure of the U.S. (New York:

nature.28 These are shown in row a of

Brookings Institution, 1938), pp. 50-156; Friedman

and Kuznets, op. cit., p. 247; and Survey of Current Table 2 under the assumption of a uni-

Business, April, 1944, Table 4, p. 19, and July, 1951,

Table 8, p. 15. 28 See formulae on p. 286.

TABLE 1 *

WAGE AND SALARY INCOME OF MALE WORKERS IN THE EXPERIENCED CIVILIAN

LABOR FORCE WHO WORKED 50-52 WEEKS IN 1949

Income

brackets

($000's). 0-0.5 0. 5-1 1-1.5 1.5-2 2-2.5 2.5-3 3-3.5 3.5-4 4-4.5 4.5-5 5-6 6-7 7-10 10 or

more

Per cent

distribu-

tion .... 1.8 2.7 4.8 7.7 14.0 15.0 18.0 11.9 8.2 4.5 5.6 2.3 2.0 1.4

* Source: Occupational Characteristics (Census Special Rept. P-E No. 1B), Table 23, p. 245.

TABLE 2

ACTUAL AND THEORETICAL COEFFICIENTS OF DISPERSION AND SKEWNESS

ALL "FULL TiME"

WORKERS WORKERS

(1) (2) (3)

Coefficient of dispersion (Theoretical* f(a) 0.43 0.43 0.43

Q9 - Q5 J (b) 0.48 0.48 0.48

Q50 lActualt 1.68 1.45 1.36

Coefficient of skewness fTheoretical* f(a) 0.11 0.11 0.11

(Q9 - Q50) - (Q50-Q5) (b) 0.22 0.22 0.22

Q95 -Q5 lActualt 0.24 0.39 0.39

* The measures of dispersion and skewness are based on differ

tiles in the distribution of training. These measures are more sensitive and of greater interest in our context

than the standard ones based on quartiles. Differences between the 5th and 95th percentiles in the educa-

tional distribution of the male U.S. population amounted to 14-16 years of schooling, according to the

1950 Census (Vol. II, Part I: U.S. Summary, Table 115, p. 236). A more appropriate estimate is that of

11 years obtained from occupational data (see n. 12 above) as the difference between the length of working

life of professional and technical groups and the least-trained laborers, which is interpreted as the number

of years of income postponement. These occupational groups are approximately coextensive with the lowest

and highest deciles of the occupational distribution; hence the 5th and 95th percentiles used in my measures

correspond to their median positions. Since the highest schooling classification in the census data is 16 years

or more, the lowest for our purposes is 5-7 years, and the middle figure is 12. Income figures by age for these

three training levels were shown in Fig. 2. The discount rate was conservatively put at 4 per cent and the

length of working life of unskilled workers at 51 years (cf. n. 12).

t Actual measures are computed from the distribution in Table 1. Unfortunately, that distribution

includes males who worked part-time (though during the full period). This factor tends to impart a down-

ward bias to "actual" skewness. A rough correction for this bias is achieved by eliminating all earnings

below $1,500 (col. 2) and below $2,000 (col. 3), even though this may result in an upward bias.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

294 JACOB MINCER

form flow of earnings during the working tion of earnings is abstracted from (row

life, in row b under the assumption that a), the training factor "explains" about a

the shapes of the 1949 cross-sectional life- third of the existing dispersion and

paths (as shown in Fig. 2) constitute the skewness; when age variation is intro-

expectation which is discounted.29 These duced (row b), the theoretical dispersion

theoretical coefficients were then com- is increased only slightly, but the extent

pared with corresponding coefficients of skewness "accounted for" by the

calculated from the actual distribution theory is increased considerably.

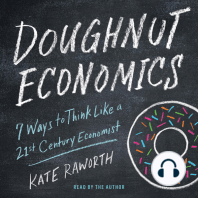

6000

LIFE PATHS OF INCOME YEARS

OF

5000 ACTUAL SCHOOL

THEORETICAL

U.S. MALES, 1949 16 AND

4000 OVER

z3000 - 12

0

z

5-7

2000 /

15 25 35 45 55 65

AGE

Source: U.S. Census of Population (1950), Ser. P-E, No. 5-B: Education, Tables 12, 13

Fig. 2.-Actual and theoretical life-paths of income, U.S. males, 1949

of earnings of fully employed workers in AGE AND INCOME DISPERSION

1949 (Table 1). From the comparison in A striking demonstration of the in-

Table 2 it appears that when age varia-

crease in income dispersion with age

29 The dashed lines in Fig. 2 were obtained by when the aggregate of spending units is

shifting the upper two solid lines downward to the

partitioned into age groups is provided in

level at which all present values are equalized (at

age fourteen). For purposes of discounting, the low- a recent study based on 1948 data com-

est income path was extrapolated back to age four- piled by the Federal Reserve Board's

teen, the middle one to age nineteen. The use of

annual Survey of Consumer Finances.

income rather than earnings figures may bias the

slopes upward; abstraction from similar trends in The systematic positive relation between

education and earnings may impart a counteracting age and family income inequality is re-

bias. The procedure is clearly to be viewed as grop-

flected in a consistent and pronounced

ing for some orders of magnitude rather than as

estimating in any more rigorous sense of the word. drift of Lorenz curves away from the line

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL 295

of equality with increase in age.30 Ac- EDUCATION AND INCOME DISPERSION

cording to the author, "this relation be- When income recipients are classified

tween the degree of income concentra- by educational background, that is, by

tion and age is one of the most interest- years of schooling as defined in the cen-

ing and perhaps important findings of the sus, the expected increase in income dis-

study." That this relation between in- persion with level of training appears as

come inequality is just as pronounced in shown in Figure 4.32

100

90 Age Groups

25-314

80 35-44

45-54 I

70' 55-64

:60

50

$40

to

05-,

30 a

20

10

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Percentage of' income recipients

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, Consumer Income, Ser. P-60, No. 16, Table 3, p. 13

FIG. 3.-Lorenz curves of 1953 income of males, by age, United States

incomes of persons as in those of familiesOCCUPATION AND INCOME DISPERSION

is seen in Figure 3. The same phenome- Let us now turn to an occupational

non appears in a variety of data differingclassification of income recipients. Figure

in time, place, and definition of income 5 presents Lorenz curves of earnings of

or recipient unit.31 male workers in several broad occupa-

32The same mean ($12,000) was assigned to the

30 J. Fisher, "Income, Spending, and Saving

upper, open-ended class in the three distributions.

Patterns of Consumer Units in Different Age

Groups," Studies in Income and Wealth, XV (New Consequently, inequality of groups with greater

education is underestimated relative to the others.

York: National Bureau of Economic Research,

1952), 83. For additional empirical instances of the relation be-

tween education and income inequality see Mincer,

31 See Mincer, op. cit., pp. 79-81. op. cit., pp. 81-85.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

296 JACOB MINCER

tional groups in the United States in of part-period and part-time workers is

1953.33 These conform to theoretical bound to create an "excess" income dis-

expectations insofar as income inequal- persion (relative to the theory) at the

ity within professional and managerial lower levels of the occupational and edu-

groups is greater than within clerical and cational classifications. The more ef-

skilled manual workers. Unskilled work- fective the exclusion of part-year in-

ers, however, show a greater inequality comes from the annual distributions of

100

7-3 years, elementary

90- 1, years, high school

Act.- 1 or more years, college

70

4) /

5 60 -9

40 -

a. 30-

20

10

C

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 30 90 100

Percentage of income recipients

Source: U.S. Census, Current Population Reports, Ser. P-60, No. 3, Table 13, p. 22

FIG. 4.-Education and income inequality, United States, 1946 (urban males, 25-65 years old)

than the other groups, particularly at the the groups under study, the more closely

lower ranges of the distribution. This do the results conform to theoretical

partial discrepancy between theory and predictions.

fact appears in most data that include all Some doubts about the meaningful-

workers regardless of the length of their ness of the findings for occupational

employment during the year. I have groups presented in Figure 5 are raised

shown elsewhere34 that the variation in by the heterogeneity of these broad occu-

man-hours introduced by the inclusion pational groups. In each such group in-

come dispersion might be largely a

33For comparable information about intra-

occupational income dispersion for various dates, product of concealed interoccupational

places, and definitions see ibid., Table 111-8, p. 87. income differences among more detailed

34 Ibid., pp. 66-70, and passim. and homogeneous occupations included

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL 297

in the broad classification. The problem they separate wage and salary incomes

may be rephrased in the following terms: of full-period36 workers from those of all

Does the hypothesized relation between workers.

occupational rank and intra-occupation- Using income shares of top quintiles

al dispersion, which seems to exist in of workers in each detailed occupation

broad occupational groups, also hold as a measure of intra-group inequality,

true for more detailed occupations? we can examine the existence of a rela-

90 -.-- Managers (salaried) /

------Professionals (salaried) /

---Clerical

-0 -._-Craftsmen & Operatives / ,'

. .......Laborers & Service

70 -

V4

0 50

040-

30-

20-

10

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 8o 90 100

Per cent of incane recipients

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, Consumer Income, Ser. P-60, No. 16, Table

FIG. 5.-Wage and salary incomes of employed males, non-farm, United States, 1953 (1

and over).

An attempt to answer such a question tion between such inequality and the

involves breaking down the broad occu- occupational rank of the groups. One

pational groups into more detailed com- way of doing this is to inquire whether

ponent occupations and studying their most detailed occupations in the "top"

income distributions. Fortunately, a broad groups (professional, managerial)

recent census monograph breaks down tend to have larger quintile shares than

the large groups into 118 more detailed occupations in the intermediate groups,

occupations and gives income distribu- and so on. Table 3 indicates a positive

tions and measures of income dispersion answer in terms of median shares and

for each of the component groups.35 The mid-ranges of shares for component oc-

data are suitable for our purposes, since cupations within the broad groups. Thus

35 Miller, op. cit., Table C-5, pp. 193-96. 36 Persons working 50 weeks or more in 1949.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

298 JACOB MINCER

when the shares of top quintiles are ar- ences in levels of earnings in the hier-

rayed in order of increasing size for the archy of occupations are due to differ-

28 subgroups of "craftsmen and fore- ences in training required by them. Thus,

men," the median quintile share is 30.2, within the framework of the model, the

and the 14 central subgroups have quin- statement that the amount of intra-oc-

tile shares running from 28.0 to 31.4 per cupational dispersion is positively re-

cent of the aggregate income of the sub- lated to occupational rank can be re-

group. As is seen, the medians follow placed by an equivalent one, namely,

the occupational rank. However, the that dispersion is positively related to

wide mid-range for clerical workers de- levels of earnings in the occupational

prives the median of that group of much groups.

significance, since it indicates an absence Thus we could, in effect, use average

of central tendency. earnings of groups as indicators of their

TABLE 3*

INCOME INEQUALITY IN DETAILED OCCUPATIONS AND

OCCUPATIONAL STATUS, U.S., 1949

(Male Full-Year Wage and Salary Workers) t

Professional Clerical Laborers

and and and

Group Managerial Sales Craftsmen Operatives Service

Median quintile share 38.2 35.6 30.2 29.6 28.7

Midrange of quintile

shares ........... 35.8-44.2 26.3-42.8 29.1-32.7 28.0-31.4 28.0-30.9

* Source: Miller, op. cit., Table C-5, pp. 193-96.

f Weeks worked, as defined in the 1950 Population Census includes all weeks in 1949 during which any work

was performed. Persons who did any amount of work during each of 50 weeks in 1949 were counted as full-year

workers. The variation in man-hours due to the sizable proportion of part-time workers in many occupations

obscures the relation we are studying. No direct information is available on the extent of part-time work in the

detailed occupations. Frequency distributions of earnings provided in Miller, op. cit., Table C-2, pp. 179-81, were

used to exclude 12 occupations in which more than 10 per cent of workers earned less than $1,000, working 50 weeks

or more in 1949. Such low earnings in groups of male, non-farm, full-period workers can only be a reflection of part-

time work or of income received to a large extent in a non-monetary form. The excluded occupations are: clergy-

men; musicians and music teachers; messengers; newsboys; attendants; private household workers; charmen;

janitors and porters; service workers (n.e.c.); fishermen and oystermen; lumbermen, raftsmen, and woodchoppers;

laborers in wood production; and laborers in wholesale and retail trade.

An alternative approach to the study occupational rank and correlate those

of the relation between occupational with the shares of top quintiles in the

rank and income inequality in detailed respective occupations. In reality, of

occupational groups is to rank these course, the simplifying assumption that

groups independently instead of fitting levels of earnings reflect occupational

rank (training) exclusively is untenable.

them into the broad ranks, as in Table 3.

Many other factors, compensatory or

However, with over a hundred occupa-

not, influence these levels, especially in

tions, ranking by the amount of training

the short run, and more so when small

or skill is a formidable task. Direct in-

differences in levels are distinguished.

formation about the ranking criterion is

Yet, despite the impossibility of identi-

not available in any quantitative form,

fying and eliminating all such disturbing

and, with so many groups, "common factors from the data, when this pro-

sense" will not lead different investiga- cedure was followed, a positive correla-

tors to the same results. tion coefficient of r = +0.77 was ob-

One "objective," though indirect, tained.37 "Occupational rank," in our

ranking procedure is implicit in the

37 After excluding the twelve occupations listed

theoretical model. In the model, differ-

in the note to Table 3.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL 299

sense, is a factor that cannot be dis- From the point of view of organization

missed in studies of income inequality of the production process, an industry

within component population groups. is a particular combination of factors of

production. When labor is subdivided by

MIXED COMPONENT GROUPS

occupations differing in training and

When the aggregate income distribu- skill, it can be viewed as a set of distinct

tion is broken down by any criterion factors of production differing in the ex-

other than occupation or age, it yields tent of capital accumulated in them. As

component groups which generally differ with non-human capital, some indus-

in occupational composition and age tries have high "capital ratios," other

distribution. When such differences in low ones, the state of the arts in each

composition are pronounced, the findings industry being what it is. Given full

that the more highly trained'workers are utilization of labor (that is, abstracting

characterized by both higher income from variations due to part-period earn-

levels and greater income inequality can ings), we should expect a greater dis-

be utilized to predict the rank order of persion of earnings in industries with

income inequalities of the component relatively many professional and man-

groups. agerial workers than in those with rela-

Let each component group consist of tively few.

several occupational strata. It can be That the occupational composition,

shown that inequality in a component or what may be called the average level

group is a "weighted" sum of the in- of human capital, is an important factor

equalities within strata, with "weights" in determining the extent of intra-

reflecting the relative sizes and relative industry income dispersion is evident on

income levels of the strata.38 Therefore, several levels of aggregation:

the larger the proportion39 of "top" oc- Table 4 presents data on income in-

cupational strata, such as professionals equality and the occupational composi-

and managers, in a group, the larger the tion within ten major industrial groups.

income dispersion in the group. Geo- The occupational composition is that of

metrically speaking, a greater weight at- 1950 as reported in the census. The in-

tached to upper occupational groups ex- equality measure, the income share of

tends the right-hand tail of the income the top quintile of workers, refers to

distribution of the occupation-mix. wages and salaries in 1949 and total

DISTRIBUTIONS BY INDUSTRY

money incomes in 1953 and 1954. In all

three years inequality is positively as-

When the distribution of wages and

sociated with the proportion of highly

salaries is disaggregated by industrial

trained occupations (professional, tech-

origin, the component distributions of

nical, and managerial): the coefficient of

earnings must, to some extent, reflect dif-

rank correlation is +0.85 in 1949, +0.93

ferences in the occupational compositions

in 1953, and +0.80 in 1954.

of the various industries. Such differ-

At a more detailed level of aggrega-

ences exist, no matter what boundaries

tion,40 the role played by occupational

are imposed on the concept of industry.

40 Miller's study quoted in Table 4 contains

38 For a mathematical formulation see Mincer, further breakdowns of the census wage and salary

op. cit., chap. iv, Notes 1-3. statistics into 91 intermediate industry groups.

39 Up to a point, depending on the number and These are subdivided into 117 more detailed indus-

sizes of parameters distinguished in the group (see tries. The study provides frequency distributions of

ibid.). 1949 wages and salaries as well as corresponding

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

300 JACOB MINCER

composition in creating patterns of that year, the correlation coefficient is

intra-industry wage and salary differ- +0.72.

entials, while obscured by many other

COLOR, SEX, FAMILY STATUS, AND

factors, is still unmistakable. When the

CITY SIZE43

occupational factor represented by the

proportion of professional and man- When members of the labor force are

agerial workers4" in seventy-five census classified by color, sex, family status, or

intermediate industry groups42 in 1949 city size, the resulting groups exhibit

is correlated with income shares of top pronounced differences in occupational

quintiles of workers in those industries in and age characteristics. As before, dif-

TABLE 4*

OCCUPATIONAL COMPOSITION AND INCOME INEQUALITY IN INDUSTRIES

U.S. MALE WORKERS, TEN BROAD INDUSTRY GROUPS,

1949, 1953, 1954

PROPORTION OF "Top" SHARE OF ToP QUINTILE

OCCUPATIONS 1949 1953 1954

INDUSTRY (1) (2) (3) (4)

Mining ....................... 6.7 36.5 34.4 38.7

Construction ......... ......... 7.7 39.1 39.3 41.4

Manufacturing ....... ......... 10.0 38.0 37.4 38.1

Transportation ....... ......... 9.0 34.4 34.8 37.2

Wholesale trade ........... 17.5 43.1 46.8 44.8

Retail trade ................... 15.6 41.6 43.5 46.3

Finance and Insurance......... . 25.9 45.4 47.0 48.0

Entertainment and recreation ... 40.2 52.6 59.5 n.a.

Business service ............... 12.8 41.8 44.6 45.3

Professional service ..... ....... 60.0 42.8 47.7 50.8

* Sources: Col. 1: Occupational Characteristics (Census Special Rep

p. 290. Col. 2: H. P. Miller, "Changes in the Industrial Distribution of Wages in the U.S., 1939-

1949," Conference on Research in Income and Wealth (National Bureau of Economic Research,

1956), Appendix Table B-3. Col. 3: Census Current Population Reports, P-60, No. 16, Table 6, p. 18.

Col. 4: Census Current Population Reports, P-60, No. 19, Table 6, p. 18.

means, medians, quartiles, and income shares of ferences in the training-mix produce pre-

quintiles for each industry. The recipient units are dictable patterns of income inequality.

males, fourteen years of age and over, including

part-period and part-time workers (Miller, op. cit., Roughly speaking, the greater the aver-

Appendix Tables B-i and B-3). age amount of training in the group, the

41 Proportions were computed from Occupational greater the inequality in its income dis-

Characteristics (Census Special Rept. P-E, No. IB),

tribution.

Table 134, p. 290.

Thus earnings of full-year employed

42 These contained over 90 per cent of all male

wage and salary workers. The exclusion of sixteen non-white workers show less inequality

industries from the correlation is the result of a than those of similar white workers;

crude, but conservative, attempt to eliminate part-

period workers from the distributions: industries

earnings of female workers are less dis-

with over 20 per cent of workers receiving less than persed than earnings of male workers,

$1,000 during the year were excluded as being too

when part-period earnings are excluded;

strongly affected by the part-period income vari-

able. These were agriculture, forestry, fisheries, earnings of male full-period workers who

lumber and wood, printing and publishing, food- are heads of families are more unequal

stores, five and ten cent stores, gasoline service

stations, drugstores, eating and drinking places, than those of single men; and, finally, in-

retail florists, private households, hotels and lodg-

ings, dress and shoe repair, theaters and motion 43 For statistical details and sources see Mincer,

pictures, and miscellaneous entertainment. op. cit., pp. 109-27.

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

INVESTMENT IN HUMAN CAPITAL 301

come inequality increases with city ductivity is reflected in increasing earn-

size.44 ings with age, up to a point when bio-

logical decline begins to affect productiv-

III. SUMMARY

ity adversely. The important difference

The implications for income distribu- among occupational groups is that, on

tions of individual differences in invest- the whole, increases in productivity with

ment in human capital have been derived age are more pronounced, and declines

in a theoretical model in which the are less pronounced, in jobs requiring

process of investment is subject to free greater amounts of training.

choice. The choice refers to training dif- When the positive relation between

fering primarily in the length of time it investment in human capital and the

requires. Since the time spent in training growth of productivity is incorporated

constitutes a postponement of earnings in the model, the following results are

to a later age, the assumption of rational produced: First, interoccupational dif-

choice means an equalization of present ferences increase, because the present

values of life-earnings at the time the value of a life-flow of income of given

choice is made. As Adam Smith ob- size is smaller, the steeper the positive

served, this equalization implies higher slope and the later the peak of the age-

annual pay in occupations that require income curve. Second, because of the

more training. increasing age gradient, intra-occupa-

Interoccupational differentials are tional dispersion must increase with "oc-

therefore a function of differences in cupational rank." In other words, "verti-

training. According to the model, this cal" occupational groupings exhibit a

function is of a very simple form and can positive correlation between income

be summarized in the principle that abso- levels and income dispersion. This corre-

lute differences in the length of training lation, even when restricted to absolute

result in percentage differences in annual dispersion, once more introduces positive

earnings. It follows that, as long as the skewness in the aggregative distribution.

distribution of training is not sub- Thus the skewness is due to patterns of

stantially negatively skewed, the dis- interoccupational as well as intra-occu-

tribution of earnings must be positively pational income differences. Moreover,

skewed. the increasing divergence with age of

Intra-occupational differences arise life-paths of earnings among different

when the concept of investment in hu- occupations implies that inequality of

man capital is extended to include ex- income within age groups increases with

perience on the job. Age measures both age. Finally, any decomposition of the

the process of acquiring experience and aggregate by criteria other than age,

biological growth and decline. The education, and occupation produces

growth of experience and hence of pro- groups which constitute training and age

44 The same explanation holds for the systematic "mixes." The previous conclusions im-

increase in income levels with city size, which is a ply that income dispersion in such

more familiar phenomenon. The increase in income

level with city size is more apparent in the statistics

groups must be positively related to the

that do not separate full-period from part-period average amount of investment in human

workers. The greater proportion of part-period work- capital in them. Breakdowns by indus-

ers in smaller communities accentuates the differ-

try, color, sex, and city size were

ences in income levels, while it obscures the differ-

ences in income variances. analyzed in these terms. As we have seen,

This content downloaded from

132.174.254.252 on Fri, 28 Aug 2020 00:48:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

302 JACOB MINCER

the empirical evidence is clearly con- choice of longer training, the compensa-

sistent with all the implications of the tory differences are augmented by a dif-

model about the effects of education, oc- ferential ascribable to ability alone. The

cupation, and age on patterns of per- financial outlays incurred in training in-

sonal income distribution. crease the compensatory differences in a

It is useful, in conclusion, to point out way that magnifies dispersion and par-

some limitations of the present study so ticularly skewness in the aggregative dis-

as to avoid possible misinterpretations. tribution. They may, indeed, increase the

In terms of predictive power, the limita- differences beyond the amount necessary

tions are quite obvious. The model pre- for equalization of present values by

dicts the existence of empirical regulari- sharply restricting supply. Finally, when

ties such as aggregative skewness and incomes rather than earnings are con-

ordinal patterns of dispersion in some sidered, the positive association of prop-

broad classifications of income. It was erty incomes with occupational level and