Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Asdfasdfadf

Uploaded by

Anders NæssOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Asdfasdfadf

Uploaded by

Anders NæssCopyright:

Available Formats

1848 J. Hawthorne, A.

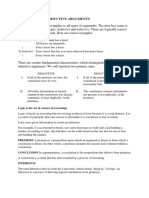

Logins

truth, and that there is a threshold level of justification required for a belief

to be considered ‘justified’. (Huemer 2001: 396, n18)

But there are important differences between ‘tall’ and ‘justified’ that should not

be ignored. In particular, ‘justified’ has hallmarks of what Unger and Kennedy call

‘absolute gradable adjectives’, ones which are more naturally associated with

endpoints on a scale than thresholds on a scale. In this connection, it bears emphasis

that one of the standard tests for absolute gradable adjectives is susceptibility to

modifiers like ‘completely’. It is unacceptable to combine such modifiers with

‘tall’—‘John is completely tall’ is utterly infelicitous. However, the expression

‘completely justified’ is altogether natural. Here is a second test from Kennedy: The

negation of relative gradable adjectives does not imply their antonyms, while the

negative of absolute gradable adjectives does. (‘Not tall’ does not imply ‘short’

while ‘Not pure’ does imply ‘impure’.) It is natural to think of ‘unjustified’ as the

antonym of ‘justified’, in which case, this test places ‘justified’ on the absolute side.

Some further data, while admittedly less straightforward tends towards the

categorization of ‘justified’ in the absolute category: ‘X is F, but Y is more F/Fer’

sounds considerably more marginal for absolutes than for relatives. Thus while ‘X is tall

but Y is taller’ is a very natural everyday use of tall, ‘x is flat but y is flatter’ is a little more

awkward sounding. (We don’t want to go so far as to say it is uninterpretable or totally

bizarre, merely that it sounds like a slightly more marginal or creative use of language.)

And we can report that ordinary informants tended to classify ‘x is justified and y is more

justified’ as towards the marginal end. (The tendencies of philosophers were more

haphazard. Certain epistemologists we asked were sufficiently imbued with a theory of

how justification works as to find ‘x is justified and y is more justified’ to be completely

straightforward.) For absolutes, the construction ‘x is F but is not completely F’ tends to

be marginal. In line with this, ‘Her suspicion/view/belief that the stock market will crash

is justified but not completely justified’ seems pretty marginal.

Kennedy (1999) notes that within the category of absolutes there are two

subcategories: Maximal absolutes are associated with the maximal degree of a scale.

Meanwhile minimals are associated with the property of having any positive degree

whatsoever along a scale. ‘Flat’ is a maximal—it tends to be associated with being

maximally flat, while open is minimal—any degree of openness counts as being

open. ‘Justified’ patterns more like a maximal. For example, minimals but not

maximals combine felicitously with ‘slightly’. But ‘slightly justified’ is extremely

awkward. (Alvin Goldman includes ‘slightly justified’ on his list of graded uses of

‘justified’, but that does not at all comport with the habits of English speakers12).

Similarly, for maximal gradables, ‘x is F but could have been more F’ is pretty

marginal (Kennedy notes for example that ‘X is straight but could have been made

straighter’ is a bit odd). In line with this, an ‘The stockbroker was justified in

12

See, Goldman: ‘‘Support for reliabilism is bolstered by reflecting on degrees of justifiedness. Talk of

justifiedness commonly distinguishes different grades of justifiedness: ‘fully’ justified, ‘somewhat’

justified, ‘slightly’ justified, and the like.[..] These distinctions appear to be neatly correlated with degrees

of reliability of belief-forming processes.’’ (Goldman 1986: 104).

123

You might also like

- Chap2 Austin TruthDocument18 pagesChap2 Austin TruthCarolina CMNo ratings yet

- Logic and Legal Reasoning: A Guide For Law StudentsDocument10 pagesLogic and Legal Reasoning: A Guide For Law StudentsNigel Lorenzo ReyesNo ratings yet

- A Brief Overview of Logical TheoryDocument6 pagesA Brief Overview of Logical TheoryHyman Jay BlancoNo ratings yet

- Self-Reference and The Acyclicity of Rational Choice: Philosophy Department. Columbia York. NY 10027. USADocument24 pagesSelf-Reference and The Acyclicity of Rational Choice: Philosophy Department. Columbia York. NY 10027. USAAndreea MărgărintNo ratings yet

- CCT 1Document24 pagesCCT 1Paras BhatnagarNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Philosophy Primary Bearers Truth Belief Propositional Attitudes Referents Meanings SentencesDocument4 pagesContemporary Philosophy Primary Bearers Truth Belief Propositional Attitudes Referents Meanings SentencesMalote Elimanco AlabaNo ratings yet

- Written Report (3 and 4)Document20 pagesWritten Report (3 and 4)Luriza SamaylaNo ratings yet

- Legal Technique and LogicDocument10 pagesLegal Technique and LogicLotionmatic LeeNo ratings yet

- Probabilistic LogicDocument9 pagesProbabilistic Logicsophie1114No ratings yet

- SemanticsDocument9 pagesSemanticsMuhamad IbrohimNo ratings yet

- AsdfasdfadsfDocument1 pageAsdfasdfadsfAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary and LogicDocument4 pagesVocabulary and LogicRommel L. DorinNo ratings yet

- Deductive and Inductive Arguments ArgumentDocument10 pagesDeductive and Inductive Arguments ArgumentLeit TrumataNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Meaning and Kinds of ReasoningDocument14 pagesUnit 1 Meaning and Kinds of ReasoningSonal MevadaNo ratings yet

- Truth-Bearers and The Liar - A Reply To Alan Weir by L. Goldstein (2001)Document12 pagesTruth-Bearers and The Liar - A Reply To Alan Weir by L. Goldstein (2001)Tony MugoNo ratings yet

- Beyond Good and EvilDocument18 pagesBeyond Good and EvilfNo ratings yet

- Module 1 LogicDocument9 pagesModule 1 LogicJunivenReyUmadhayNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7: Evaluating ArgumentsDocument47 pagesChapter 7: Evaluating ArgumentsAlliah FajardoNo ratings yet

- Logic and Fallacies CompilationDocument21 pagesLogic and Fallacies CompilationDan Gloria100% (1)

- Summary Of "Introduction To Logic" By Irving Copi: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Introduction To Logic" By Irving Copi: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- RmsacceptanceDocument16 pagesRmsacceptanceapi-339415958No ratings yet

- Situations in Which Disjunctive Syllogism Can Lead From True Premises To A False ConclusionDocument8 pagesSituations in Which Disjunctive Syllogism Can Lead From True Premises To A False ConclusionDren ViiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Moore and ParkerDocument8 pagesChapter 2 Moore and Parkerrt1220011No ratings yet

- Deductive and Inductive Arguments: A) Deductive: Every Mammal Has A HeartDocument9 pagesDeductive and Inductive Arguments: A) Deductive: Every Mammal Has A HeartUsama SahiNo ratings yet

- Evaluating ArgumentsDocument32 pagesEvaluating ArgumentsSamuel AyladoNo ratings yet

- Intro To Philo LP - Arguments 22Document13 pagesIntro To Philo LP - Arguments 22Eljhon monteroNo ratings yet

- Gentle introduction to logic and fallaciesDocument13 pagesGentle introduction to logic and fallacieslaw tharioNo ratings yet

- Deductivism Within Pragma-DialecticsDocument16 pagesDeductivism Within Pragma-DialecticsDaniel CabralNo ratings yet

- Circular Reasoning Written ReportDocument5 pagesCircular Reasoning Written ReportChengChengNo ratings yet

- 1.intro LogicDocument18 pages1.intro LogicMary Jane TiangsonNo ratings yet

- Logical ReasoningDocument244 pagesLogical ReasoningAjay KharbadeNo ratings yet

- GMAT Critical ThinkingDocument43 pagesGMAT Critical ThinkingWei WangNo ratings yet

- Categorical Syllogism GuideDocument13 pagesCategorical Syllogism GuideAnonymous 9hu7flNo ratings yet

- An Argument Against General Validity - Rohan FrenchDocument6 pagesAn Argument Against General Validity - Rohan FrenchMiguel GarciaNo ratings yet

- Logic FallaciesDocument27 pagesLogic FallaciesJohnMirasolNo ratings yet

- Strawman Fallacy - Douglas WaltonDocument14 pagesStrawman Fallacy - Douglas WaltonFernanda Trejo BermejoNo ratings yet

- Ayer's Views on Verification of Negative StatementsDocument8 pagesAyer's Views on Verification of Negative StatementscbrincusNo ratings yet

- FallaciesDocument10 pagesFallaciesRed HoodNo ratings yet

- Basic Logical ConceptsDocument91 pagesBasic Logical ConceptsAbdul FasiehNo ratings yet

- Last LogicDocument17 pagesLast LogicmusaaigbeNo ratings yet

- Induction Vs Deduction WRDocument3 pagesInduction Vs Deduction WRAc MIgzNo ratings yet

- There Is No Fallacy of Arguing From AuthorityDocument19 pagesThere Is No Fallacy of Arguing From AuthorityRafael Do Amaral PrudencioNo ratings yet

- Argumentative EssayDocument23 pagesArgumentative EssayTamyy VuNo ratings yet

- Analyzing ImperativesDocument2 pagesAnalyzing ImperativesPantatNyanehBurikNo ratings yet

- Synthese All Rights Reserved by D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht-ItollandDocument36 pagesSynthese All Rights Reserved by D. Reidel Publishing Company, Dordrecht-ItollandGuido PalacinNo ratings yet

- Logical Fallacies An Encyclopedia of Errors of ReasoningDocument8 pagesLogical Fallacies An Encyclopedia of Errors of ReasoningJulian Paul CachoNo ratings yet

- Decimate: The Words To Be UsedDocument1 pageDecimate: The Words To Be UsedIliasNo ratings yet

- 5 One Ought Too ManyDocument23 pages5 One Ought Too ManyDaysilirionNo ratings yet

- Contextualism in EpistemologyDocument28 pagesContextualism in EpistemologyMilosh PetrovicNo ratings yet

- Encoding Speaker Perspective - EvidentialsDocument36 pagesEncoding Speaker Perspective - EvidentialsKclhNo ratings yet

- The Concessive Response To SkepticismDocument12 pagesThe Concessive Response To SkepticismJohn Di GiacomoNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking & LogicDocument26 pagesCritical Thinking & LogicWeng DelarosaNo ratings yet

- Deductive InductiveDocument22 pagesDeductive InductiveJerome ChuaNo ratings yet

- Why Language Vague Optimality ModelsDocument15 pagesWhy Language Vague Optimality ModelsnasdaqtexasNo ratings yet

- Traditional Square of OppositionDocument1 pageTraditional Square of OppositionDenise GordonNo ratings yet

- Some Basic Concepts: Definition: Logic Is The Study of Methods For EvaluatingDocument8 pagesSome Basic Concepts: Definition: Logic Is The Study of Methods For Evaluatingroy rebosuraNo ratings yet

- Logic KPDocument7 pagesLogic KPapi-3709182100% (2)

- Fallacies (Logic& Fallacies 1-45)Document11 pagesFallacies (Logic& Fallacies 1-45)Virgil MunteaNo ratings yet

- 'Exists' As A Predicate - A Reconsideration PDFDocument6 pages'Exists' As A Predicate - A Reconsideration PDFedd1929No ratings yet

- AsdfDocument1 pageAsdfAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- Graded epistemic justification and probability scalesDocument1 pageGraded epistemic justification and probability scalesAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- AsdfasdfDocument1 pageAsdfasdfAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- AsdfasdfadsfDocument1 pageAsdfasdfadsfAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0022096514001763 MainDocument13 pages1 s2.0 S0022096514001763 MainAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- Wearing, C. (2011) - Metaphor, Idiom, and Pretense. Noûs, 46 (3), 499-524Document26 pagesWearing, C. (2011) - Metaphor, Idiom, and Pretense. Noûs, 46 (3), 499-524Anders NæssNo ratings yet

- Nozick's experience machine thought experiment reevaluatedDocument1 pageNozick's experience machine thought experiment reevaluatedAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- Telling It Like It Isn't: A Review of Deception Theory and ResearchDocument16 pagesTelling It Like It Isn't: A Review of Deception Theory and ResearchAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- Just go ahead and lie: Why misleading is not morally preferable to lyingDocument7 pagesJust go ahead and lie: Why misleading is not morally preferable to lyingAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- 02Document1 page02Anders NæssNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Psychology 517Document1 pagePhilosophical Psychology 517Anders NæssNo ratings yet

- 520 D. WeijersDocument1 page520 D. WeijersAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- Att Föda Hemma. en Kvalitativ StudieDocument8 pagesAtt Föda Hemma. en Kvalitativ StudieAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- 05 AsdfasdfDocument1 page05 AsdfasdfAnders NæssNo ratings yet

- Mary WollstonecraftDocument9 pagesMary WollstonecraftAnders Næss100% (1)

- Sop Guide PDFDocument2 pagesSop Guide PDFAkshay ChandrolaNo ratings yet

- Medical Hypnosis For Burn VictimsDocument5 pagesMedical Hypnosis For Burn VictimsbhujabaliNo ratings yet

- IA DraftDocument29 pagesIA DraftvishaalNo ratings yet

- Understanding Sex, Gender and SexualityDocument3 pagesUnderstanding Sex, Gender and SexualityBernadeth P. Lapada100% (1)

- Parent-Child Relationship EssayDocument4 pagesParent-Child Relationship Essayapi-4571701600% (1)

- Student attitudes towards math explored using iPad video diariesDocument20 pagesStudent attitudes towards math explored using iPad video diarieskarolina_venny5712No ratings yet

- Tema 25Document10 pagesTema 25vanesa_duque_3No ratings yet

- After 2015 - 3D Wellbeing - IDS - McGregor and Sumner IF9.2 PDFDocument2 pagesAfter 2015 - 3D Wellbeing - IDS - McGregor and Sumner IF9.2 PDFIan Last100% (1)

- Practice-as-Research in Musical Theatre: A ReviewDocument24 pagesPractice-as-Research in Musical Theatre: A ReviewShannonEvisonNo ratings yet

- Infancy and Toddlerhood Period of DevelopmentDocument3 pagesInfancy and Toddlerhood Period of Developmentapi-269196462No ratings yet

- Group 6 Chapter 1 5Document51 pagesGroup 6 Chapter 1 5Katherine AliceNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behavior: Definition, Models, ConceptsDocument38 pagesOrganizational Behavior: Definition, Models, ConceptsnandhiniNo ratings yet

- A Study of Creative ThinkingDocument192 pagesA Study of Creative ThinkingAllan GirodNo ratings yet

- Teaching Profession AnswerDocument20 pagesTeaching Profession AnswerRezel SyquiaNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behavior NotesDocument5 pagesOrganizational Behavior NotescyntaffNo ratings yet

- Doodle Dilemma Hi ResDocument1 pageDoodle Dilemma Hi Resosgar68No ratings yet

- Deciding To Believe Bernard WilliansDocument16 pagesDeciding To Believe Bernard WilliansEderlene WelterNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - Training and Development of Human ResourcesDocument9 pagesChapter 5 - Training and Development of Human ResourcesBelle MendozaNo ratings yet

- Global Citizenship EssayDocument1 pageGlobal Citizenship Essayapi-601540070No ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, Ltd. Theory Into PracticeDocument8 pagesTaylor & Francis, Ltd. Theory Into PracticeSam BateNo ratings yet

- Effect of Examination On Curriculum at Elementary Level in Punjab: A Mixed Methods StudyDocument16 pagesEffect of Examination On Curriculum at Elementary Level in Punjab: A Mixed Methods StudyLaser RomiosNo ratings yet

- On Becoming An Edukasyon Sa Pagpapakatao (EspDocument37 pagesOn Becoming An Edukasyon Sa Pagpapakatao (EspMichael Angelo BandalesNo ratings yet

- 5 Simple Steps To Improve Your Decision MakingDocument42 pages5 Simple Steps To Improve Your Decision MakingJulius EstrelladoNo ratings yet

- How to Deal With a Manipulative CoworkerDocument4 pagesHow to Deal With a Manipulative CoworkerBudget MegamanilaNo ratings yet

- Madness and The Moon: The Lunar Cycle and Psychopathology: German Journal of Psychiatry July 2006Document6 pagesMadness and The Moon: The Lunar Cycle and Psychopathology: German Journal of Psychiatry July 2006brainhub50No ratings yet

- Kanto: A Day in The Life of A Tricycle Driver: Infant Jesus AcademyDocument3 pagesKanto: A Day in The Life of A Tricycle Driver: Infant Jesus AcademyJustine PortugalNo ratings yet

- 7 Critical Reading StrategiesDocument2 pages7 Critical Reading StrategiesNor AmiraNo ratings yet

- Creating A School Behaviour PolicyDocument8 pagesCreating A School Behaviour PolicyGeoffMossNo ratings yet

- Strengthscope Applications and Case StudiesDocument5 pagesStrengthscope Applications and Case Studiessaurs24231No ratings yet

- Little EmperorsDocument8 pagesLittle EmperorsSi Xuan LooNo ratings yet