Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Kissinger The Negotiator Sebenius en 31109

Uploaded by

Coco LuluOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Kissinger The Negotiator Sebenius en 31109

Uploaded by

Coco LuluCopyright:

Available Formats

8

Rating ? Qualities ?

Analytical

Applicable

Insider's Take

Buy book or audiobook

Kissinger the Negotiator

Lessons from Dealmaking at the Highest Level

James K. Sebenius, R. Nicholas Burns and Robert H. Mnookin • KISSINGER

THE NEGOTIATOR: Lessons from Dealmaking at the Highest Level by James

K. Sebenius, R Nicholas Burns and Robert H. Mnookin. Copyright © 2018 by

James K. Sebenius, R. Nicholas Burns, and Robert H. Mnookin. Published by

arrangement with Harper, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers • 240 pages

Social Skills / Negotiation

History

Take-Aways

• Henry Kissinger’s diplomatic work suggests a variety of negotiating techniques.

• Establish sharp, long-term goals and a clear plan to achieve them.

• To design a “negotiation campaign,” work backward from the ideal pact you have in mind.

• Combine “zooming out” on your broader strategy with “zooming in” on the personality and context of

your negotiating partner.

• Adopt a realistic approach to negotiation that considers all parties’ incentives and interests.

• The most common reason that negotiations fail is a negative or unstable “deal/no-deal balance.”

• Successful negotiations demand more than eloquent rhetoric; include rewards and punishments.

• In a strategic approach, always seize opportunities, but know that strategies are only as sound as their

underlying assumptions.

• Take a broad strategic view, focus on your counterpart and consider both viewpoints.

1 of 6

LoginContext[cu=6990912,ssoId=3639744,asp=6696,subs=7,free=0,lo=en,co=SG] 2023-02-17 10:22:42 CET

Recommendation

Harvard professor Henry Kissinger was US national security adviser and Secretary of State in the depths of

the Cold War. James K. Sebenius, R. Nicholas Burns and Robert H. Mnookin show how he negotiated the

USSR arms control deal, opened talks with China and moved toward ending the Vietnam war. Negotiating

for presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, he would “zoom out” to broad goals and “zoom in” to

personal relationships with his counterparts. Love or loathe his politics, his work offers compelling insights

into complex, high-stakes negotiations.

Summary

Henry Kissinger’s diplomatic work suggests a variety of negotiating techniques.

Many people think of former US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger as a great diplomatic negotiator. As

early as 1974, when he was still in office, 85% of Americans polled believed he was doing an excellent

job. Forty years later, more than 1,000 international relations scholars voted him the “most effective” US

secretary of state in the past 50 years. Every president since John F. Kennedy has asked for his advice, as

have CEOs and world leaders.

“While Kissinger’s conception of effective negotiation derives largely from the diplomacy

of earlier decades, we seek to assess the value and limits of his approach as a source of

guidance for today’s diplomats and others who negotiate.”

Kissinger’s international reputation and influence rests on his achievements as a negotiator. As national

security adviser and secretary of state for Presidents Richard Nixon and Gerald Ford, he spearheaded

complex, high-stakes negotiations with China, the Soviet Union, Vietnam, South Africa and Middle Eastern

nations. Kissinger’s sophisticated, consistent approach to negotiations embodies principles and practices

that are useful for diplomats and negotiators in business, finance, public policy and law.

Establish sharp, long-term goals and a clear plan to achieve them.

A negotiation between two or more parties must aim for a “target agreement” on issues they view differently

and on which their interests diverge. The patterns of emotions, debate, counterargument and nonverbal

communication matter to the ultimate outcome.

“Kissinger often reshapes the negotiating setup itself in order to enhance the value of

agreement, raise the costs of impasse – or both.”

People often view negotiation as limited to what takes place when the parties are “at the table” and to details

of personality and culture. However, Kissinger’s approach included what took place “away from the table”

– such as forming or dissolving alliances or preventing certain parties from participating in negotiations.

www.getabstract.com

2 of 6

LoginContext[cu=6990912,ssoId=3639744,asp=6696,subs=7,free=0,lo=en,co=SG] 2023-02-17 10:22:42 CET

To design a “negotiation campaign,” work backward from the ideal pact you have in

mind.

In March 1976, Ian Smith, Rhodesia’s white prime minister, announced that the black majority

wouldn’t govern there “in a thousand years.” Independent of Great Britain since the mid-1960s, Rhodesia

had a population of 270,000 whites and six million blacks. Britain failed to convince Rhodesia’s government

to accept majority rule. Near the end of President Gerald Ford’s term, Kissinger began a series of complex

negotiations with a coalition of interested parties. Less than a year later, Smith announced that he

would accept black majority rule within two years. Kissinger’s authority waned when Ford lost the 1976

election. Black majority rule in Rhodesia – which became Zimbabwe – didn’t arrive until 1979. Kissinger’s

negotiations were also pivotal in ending apartheid in South Africa.

Kissinger’s approach to Rhodesia didn’t follow the standard script. He didn’t insist on immediate “direct”

talks, which the British had already tried. He knew negotiations often fail when the motive to reject an

agreement is greater than the incentive to accept it. In Rhodesia, the main obstacle to Smith’s concurrence

was that the white population faced an immense loss of power, prestige and money if the black majority

governed.

“Your effectiveness as a negotiator can be dramatically enhanced by determination to

develop a psychological understanding of your counterparts.”

Kissinger changed the calculus by adopting an “indirect” approach. His negotiation strategy deployed a

“wide-angle lens” and offered a quick route to majority rule while assuring that foreign forces wouldn’t enter

the conflict and that a black government would respect the white minority’s rights. Kissinger engaged

European nations with a history of involvement in Africa. He managed the American response, consulting

with Congress and African-American leaders. He moved backward from the goal of an agreement for

majority rule in Rhodesia within a realistic time frame. Instead, he focused on everything that had to happen

for a successful negotiation even to take place.

Combine “zooming out” on your broader strategy with “zooming in” on the

personality and context of your negotiating partner.

Kissinger adopted a wide, historical perspective on negotiations. He was adept at zooming in on his

negotiating counterparts. Zooming in involves focusing on your counterparts as individuals – their

psychological traits, history, interests and incentives – as well as their political influence. Many negotiators

tend to focus on either broad strategic concerns or personal relationships. Kissinger combined the two styles

and tried to align them.

Kissinger saw South Africa’s support as crucial leverage in Rhodesia. With President Gerald Ford’s backing,

he promoted meeting with South African prime minister B.J. Vorster. Kissinger and Vorster’s initial

meetings coincided with a violent crackdown on protests in Soweto where hundreds of civilians were killed.

The US and the United Nations condemned the South African government’s actions. International outcry

gave Vorster an incentive to negotiate.

www.getabstract.com

3 of 6

LoginContext[cu=6990912,ssoId=3639744,asp=6696,subs=7,free=0,lo=en,co=SG] 2023-02-17 10:22:42 CET

Kissinger’s approach to Vorster was subtle. Vorster was a staunch advocate of South Africa’s racial

policies. Kissinger pointed out that majority rule in neighboring Rhodesia was inevitable. If South Africa

saw its future tied to Rhodesia’s, South Africa would face increasingly violent conflict. Kissinger offered

Vorster an opportunity to address his domestic situation peacefully. Vorster agreed to support majority rule

in Rhodesia if the white population retained certain rights.

“Effective negotiation often requires more than persuasive verbal exchange; actions

away from the table to orchestrate incentives and penalties can be crucial to induce the

desired ‘yes’.”

Kissinger combined empathy and assertiveness in these negotiations. He understood South Africa’s need to

respond to international condemnation and to avoid the consequences of supporting white minority rule in

Rhodesia. While supporting international denunciation of South Africa’s policies, Kissinger insisted that

Vorster pressure Rhodesia. Kissinger’s style of negotiating with Vorster – and then Smith – was stringent

but compassionate. He believed a harsh, demanding, immediate approach would shatter the negotiating

process.

Adopt a realistic approach to negotiation that considers all parties’ incentives and

interests.

Kissinger’s strategic approach to negotiating has five core characteristics: Begin with well-defined, long-

term aims. Don’t see the negotiation as an isolated event; also consider its larger political and historical

context. Don’t depend too much on face-to-face dynamics. Construct a precise, step-by-step plan to achieve

stated goals in person and through other actions that give you leverage and influence. Remain firm on long-

term aims, but be flexible in adapting to shifting circumstances, including actions by other parties or new

information. Be mindful of your reputation; it will affect all your other current and future negotiations.

In addition to being a strategic thinker and negotiator, Kissinger adopted a “realistic” approach to

negotiation, as contrasted with “theological” and “psychiatric” approaches. Theologians believe they can

impose their conditions top-down when one party has absolute dominance over the other. Psychiatrists

believe negotiations are valuable under all circumstances.

During the Cold War, theologians assumed economic and military dominance in advance. For example,

some Americans saw Soviet dreams of world dominance as an intrinsic part of the Soviet system and

didn’t view the Soviets as possible negotiating partners until they gave up those goals. Given that the aim

of US policy was the end of the Soviet system, the United States had no reason to enter negotiations. With

Nixon’s support, Kissinger pursued negotiations toward opening diplomatic relations with China and

forging an arms agreement with the USSR.

“Effective negotiation often requires more than persuasive verbal exchange; actions

away from the table to orchestrate incentives and penalties can be crucial to induce the

desired ‘yes’.”

Kissinger believed well-crafted agreements could serve the interests of the United States, China and the

Soviet Union. Realistic approaches to negotiations are neither blunt and confrontational nor soft and

www.getabstract.com

4 of 6

LoginContext[cu=6990912,ssoId=3639744,asp=6696,subs=7,free=0,lo=en,co=SG] 2023-02-17 10:22:42 CET

conciliatory. They are sensitive to context and shaped by the interests of all parties. They aim for positions

that serve everyone’s interest. Kissinger doesn’t believe negotiation is a general panacea for conflict, but he

does believe that agreements can produce a “realistic accommodation of conflicting interests.”

The most common reason that negotiations fail is a negative or unstable “deal/no-

deal balance.”

Kissinger emphasized how a prospective agreement would serve the interests of all the parties involved and

always pointed out the price each would pay if they failed to agree. Kissinger was often blunt about the

consequences of having no agreement.

The most common reason negotiations fail is a negative or unstable deal:no-deal balance. Examples

include the failed attempts to end Pakistan’s nuclear arms program and to arrive at a pact between Jordan

and Israel after the 1973 war. The proper balance of incentives for an agreement is central to realistic

negotiating.

“The techniques of reaching agreement, however creative, depend for their ultimate

success on the accuracy of underlying assumptions.”

When anyone involved perceives that the value of not having an agreement is greater than the value of

having one, continued talks are pointless. Changing tactics, location or procedures will serve no purpose.

Steering the process back toward possible success may require altering the structure of the game.

“Changing the game” in a negotiation can involve pushing some parties out or bringing in fresh ones,

shifting the array of subjects under discussion, or making the possibility of no agreement better for you and

worse for your counterpart. When attempting to change the game, “negotiation and consequences” go hand

in hand.

Successful negotiations demand more than eloquent rhetoric; include rewards and

punishments.

In Kissinger’s view, negotiators can’t separate what happens in a negotiation from what happens out in the

world. Negotiations aren’t an academic seminar. They involve real rewards and penalties. In the negotiations

with North Vietnam that eventually led to the 1973 Paris Peace Accords and the end of the Vietnam War,

the prospects of an agreement initially looked hopeless because Hanoi promoted its interests by rejecting

any agreement. At that point, the United States had little leverage, especially given increasing public and

Congressional hostility to the war. Kissinger changed the dynamic by involving other parties, including the

Soviets and China.

“To craft a strategy, employ a ‘wide-angle lens’ to assess the full set of potentially

relevant parties.”

Since the Chinese valued a relationship with the United States, they were willing to pressure North Vietnam.

The USSR was concerned about the evolving relationship between the US and China and had a stake in a

better relationship with the United States. The Soviets were willing to pressure the North Vietnamese to take

www.getabstract.com

5 of 6

LoginContext[cu=6990912,ssoId=3639744,asp=6696,subs=7,free=0,lo=en,co=SG] 2023-02-17 10:22:42 CET

the Paris talks more seriously. In the end, the agreement foundered because the combination of Watergate

and poor public opinion made it impossible to enforce.

In a strategic approach, always seize opportunities, but know that strategies are

only as sound as their underlying assumptions.

From Kissinger’s point of view, the negotiation for Israel’s potential disengagement from Jordan may have

had a reasonable shot. He saw that for Israel and Jordan, the eventual value of no agreement was greater

than that of an agreement, so he shifted his focus elsewhere. Later, commentators claimed that Kissinger

could have made an agreement if he’d supported the Palestinians. However, this assessment concerns the

premise of his negotiation more than his strategy.

“A negotiator must, at a minimum, have a target agreement in mind among parties that

often see things differently and have conflicting interests.”

Negotiating strategies and tactics depend on the assumptions that form the foundations of the entire

negotiation. Kissinger downplayed the importance of strategies and skills compared to a deep understanding

of the core issues. For him, the assumptions at play are the crucial determinants of a negotiation’s outcome.

Take a broad strategic view, focus on your counterpart and consider both

viewpoints.

Kissinger’s practice as a negotiator offers three broad core lessons: First, take a wide view for your strategy,

focus on your counterpart and always accommodate both points of view.

“Think strategically; act opportunistically.”

Second, never take for granted the truth or importance of your basic assumptions. Third, make sure you and

your team have a deep knowledge of what you are negotiating.

About the Authors

James K. Sebenius, PhD, teaches advanced negotiation at Harvard Business School. R. Nicholas

Burns teaches diplomacy and international relations at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. Robert

H. Mnookin, a leading scholar of conflict resolution, is a Harvard Law School professor.

Did you like this summary?

Buy book or audiobook

http://getab.li/31109

This document is restricted to the personal use of Johan Lim (Johan_Lim@epam.com)

getAbstract maintains complete editorial responsibility for all parts of this review. All rights reserved. No part of this review may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means – electronic, photocopying or otherwise – without prior written permission of getAbstract AG (Switzerland).

6 of 6

LoginContext[cu=6990912,ssoId=3639744,asp=6696,subs=7,free=0,lo=en,co=SG] 2023-02-17 10:22:42 CET

You might also like

- Why Read "Kissinger The Negotiator?"Document12 pagesWhy Read "Kissinger The Negotiator?"JimNo ratings yet

- Project ManagerDocument24 pagesProject Manageryadanarhtwe104No ratings yet

- Diplomacy and NegotiationDocument10 pagesDiplomacy and NegotiationRuach SakadewaNo ratings yet

- The Book on Negotiating Real Estate: Expert Strategies for Getting the Best Deals When Buying & Selling Investment PropertyFrom EverandThe Book on Negotiating Real Estate: Expert Strategies for Getting the Best Deals When Buying & Selling Investment PropertyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Purchasing Negotiation GuideDocument22 pagesPurchasing Negotiation GuideNorah NsooliNo ratings yet

- BIAM22 Negotiations Theory 191022Document18 pagesBIAM22 Negotiations Theory 191022S M Masudul HaqueNo ratings yet

- The New Project Management: Tools for an Age of Rapid Change, Complexity, and Other Business RealitiesFrom EverandThe New Project Management: Tools for an Age of Rapid Change, Complexity, and Other Business RealitiesNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Ebook PDF Essentials of Negotiation 5th Edition by Roy Lewicki PDF ScribdDocument41 pagesInstant Download Ebook PDF Essentials of Negotiation 5th Edition by Roy Lewicki PDF Scribdmelissa.barraza943100% (34)

- The Great Depression Ahead: How to Prosper in the Crash Following the Greatest Boom in HistoryFrom EverandThe Great Depression Ahead: How to Prosper in the Crash Following the Greatest Boom in HistoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (9)

- Negotiation Skills Course OutlineDocument4 pagesNegotiation Skills Course OutlineRobert ScottNo ratings yet

- The Real Estate Philosopher's Guide: The Secrets to Real Estate SuccessFrom EverandThe Real Estate Philosopher's Guide: The Secrets to Real Estate SuccessNo ratings yet

- 3 Strategic Influencing and Negotiation Skills 2015Document37 pages3 Strategic Influencing and Negotiation Skills 2015Emmanuel Lucky OhiroNo ratings yet

- Comunicative StylesDocument49 pagesComunicative StylesAmy TabaconNo ratings yet

- Bargaining for Advantage Book SummaryDocument8 pagesBargaining for Advantage Book Summaryohsomaya_798528883No ratings yet

- Value Investor Insight - March 31, 2014Document11 pagesValue Investor Insight - March 31, 2014vishubabyNo ratings yet

- Negotiation Mastery SyllabusDocument1 pageNegotiation Mastery SyllabusYadu NandanaNo ratings yet

- Outthinker FlyerDocument1 pageOutthinker FlyerGlen SaktiNo ratings yet

- Curve Benders: How Strategic Relationships Can Power Your Non-linear Growth in the Future of WorkFrom EverandCurve Benders: How Strategic Relationships Can Power Your Non-linear Growth in the Future of WorkNo ratings yet

- Why " Getting To Yes " Won't Get You There: Negotiation Skill SeriesDocument6 pagesWhy " Getting To Yes " Won't Get You There: Negotiation Skill SeriesLast_DonNo ratings yet

- SMART MONEY, Dumb Money: Beating the Crowd Through Contrarian InvestingFrom EverandSMART MONEY, Dumb Money: Beating the Crowd Through Contrarian InvestingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Trusted Advisor: 20th Anniversary EditionFrom EverandThe Trusted Advisor: 20th Anniversary EditionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- The Hidden Agenda: A Proven Way to Win Business and Create a FollowingFrom EverandThe Hidden Agenda: A Proven Way to Win Business and Create a FollowingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Getting To Win-Win NIC 202211Document18 pagesGetting To Win-Win NIC 202211Alejandro MaguerNo ratings yet

- Leasing NYC: The Insider's Guide to Leasing Office Space in ManhattanFrom EverandLeasing NYC: The Insider's Guide to Leasing Office Space in ManhattanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document16 pagesChapter 1Lệ Huyền MaiNo ratings yet

- DIASS Group 1Document20 pagesDIASS Group 1Kizzy LachicaNo ratings yet

- NegotiationDocument29 pagesNegotiationphillis zhaoNo ratings yet

- Literature Reviews For Business Management and Marketing Cohorts Slides 2022-23Document24 pagesLiterature Reviews For Business Management and Marketing Cohorts Slides 2022-23Hassan HussainNo ratings yet

- Buy, Rehab, Rent, Refinance, Repeat: The BRRRR Rental Property Investment Strategy Made SimpleFrom EverandBuy, Rehab, Rent, Refinance, Repeat: The BRRRR Rental Property Investment Strategy Made SimpleRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (21)

- Executive Program in Business Management Communication SkillsDocument31 pagesExecutive Program in Business Management Communication SkillsAkshay MeshramNo ratings yet

- Long-Distance Real Estate Investing: How to Buy, Rehab, and Manage Out-of-State Rental PropertiesFrom EverandLong-Distance Real Estate Investing: How to Buy, Rehab, and Manage Out-of-State Rental PropertiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (8)

- HLS PON FR19 CulturalBarriers 102021 EdsDocument19 pagesHLS PON FR19 CulturalBarriers 102021 EdsSpil_vv_IJmuidenNo ratings yet

- Cs of Academic and Professional CommunicationDocument24 pagesCs of Academic and Professional CommunicationWynceer Jay MarbellaNo ratings yet

- Understanding China’s Real Estate Markets: Development, Finance, and InvestmentFrom EverandUnderstanding China’s Real Estate Markets: Development, Finance, and InvestmentBing WangNo ratings yet

- Int Negotiation Tech IIDocument26 pagesInt Negotiation Tech IIolivier rasamoelinaNo ratings yet

- Chime Term Paper FinalDocument10 pagesChime Term Paper FinalkebrinaNo ratings yet

- Full download book The Mcgraw Hill Guide Writing For College Writing For Life Pdf pdfDocument41 pagesFull download book The Mcgraw Hill Guide Writing For College Writing For Life Pdf pdflori.cherry584100% (14)

- Alisdair Cornforth CVDocument2 pagesAlisdair Cornforth CVAli CornforthNo ratings yet

- Reflective WritingDocument42 pagesReflective WritingAamirNo ratings yet

- 01 Defining Critical ThinkingDocument15 pages01 Defining Critical Thinkingperry7grineNo ratings yet

- 422 - PDFsam - Joseph A. DeVito - Human Communication - The Basic Course-Pearson (2018)Document1 page422 - PDFsam - Joseph A. DeVito - Human Communication - The Basic Course-Pearson (2018)Mási de LaféNo ratings yet

- Critical+Thinking,+Thoughtful+Writing+ +A+Rhetoric+with+Readings PDFDocument574 pagesCritical+Thinking,+Thoughtful+Writing+ +A+Rhetoric+with+Readings PDFChen Da100% (5)

- 11 Secrets of Nonprofit Excellence: Merger, Transformation, and GrowthFrom Everand11 Secrets of Nonprofit Excellence: Merger, Transformation, and GrowthNo ratings yet

- Just Run It!: Running an Exceptional Business Is Easier Than You ThinkFrom EverandJust Run It!: Running an Exceptional Business Is Easier Than You ThinkNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 SlidesDocument18 pagesChapter 1 SlidesSeipati StellaNo ratings yet

- The Negotiation Fieldbook, Second Edition: Simple Strategies to Help You Negotiate EverythingFrom EverandThe Negotiation Fieldbook, Second Edition: Simple Strategies to Help You Negotiate EverythingNo ratings yet

- The Negotiator's Edge: Techniques for Winning Deals and Building SuccessFrom EverandThe Negotiator's Edge: Techniques for Winning Deals and Building SuccessNo ratings yet

- Trend NetworksDocument6 pagesTrend NetworksTanjo MusicNo ratings yet

- Lecture 3 - Efficiency in NegotiationDocument13 pagesLecture 3 - Efficiency in NegotiationCindhy ChamorroNo ratings yet

- Negotiation Skills: Approaches, Process, Factors & CommunicationDocument28 pagesNegotiation Skills: Approaches, Process, Factors & Communicationrukhsar nasimNo ratings yet

- Nov Champ BriefDocument303 pagesNov Champ BriefAmogh AyalasomayajulaNo ratings yet

- Everybody Wins (Review and Analysis of Harkins and Hollihan's Book)From EverandEverybody Wins (Review and Analysis of Harkins and Hollihan's Book)No ratings yet

- Foreign Policy Theories Actors Cases 3Rd Edition Full ChapterDocument41 pagesForeign Policy Theories Actors Cases 3Rd Edition Full Chaptersara.hendrix328100% (26)

- W13 SalesDocument39 pagesW13 SalesNikola DraskovicNo ratings yet

- Buy and Hold Is Dead (Again): The Case for Active Portfolio Management in Dangerous MarketsFrom EverandBuy and Hold Is Dead (Again): The Case for Active Portfolio Management in Dangerous MarketsNo ratings yet

- Leading for the Long Term: European Real Estate Executives on Leadership and ManagementFrom EverandLeading for the Long Term: European Real Estate Executives on Leadership and ManagementNo ratings yet

- Cross-Cultural Negotiations Integrative Negotiations: NegotiationDocument29 pagesCross-Cultural Negotiations Integrative Negotiations: Negotiationdebjyoti77No ratings yet

- Leading and Managing in 2023: A Human Focus in Disrupted TimesDocument24 pagesLeading and Managing in 2023: A Human Focus in Disrupted TimesCoco LuluNo ratings yet

- Aws Reference Architecture Multi Region Cloudfront Api Gateway RaDocument1 pageAws Reference Architecture Multi Region Cloudfront Api Gateway RaCoco LuluNo ratings yet

- Wall Street Journal 20230214Document28 pagesWall Street Journal 20230214Coco LuluNo ratings yet

- Forex Revolution Rosenstreich en 4896Document6 pagesForex Revolution Rosenstreich en 4896Coco LuluNo ratings yet

- Rules: When You StartDocument19 pagesRules: When You StartCoco LuluNo ratings yet

- 2021 H2 Market Insights Singapore Banking & FinanceDocument37 pages2021 H2 Market Insights Singapore Banking & FinanceCoco LuluNo ratings yet

- Value: Market Activity: Property TransactionsDocument3 pagesValue: Market Activity: Property TransactionsCoco LuluNo ratings yet

- AWS Certified Solutions Architect Associate - Sample Questions PDFDocument5 pagesAWS Certified Solutions Architect Associate - Sample Questions PDFRajendraNo ratings yet

- Change Management HRDocument2 pagesChange Management HRahmedaliNo ratings yet

- Quotes by Swami VivekanandaDocument6 pagesQuotes by Swami Vivekanandasundaram108No ratings yet

- Visa Vertical and Horizontal Analysis ExampleDocument9 pagesVisa Vertical and Horizontal Analysis Examplechad salcidoNo ratings yet

- Vicarious LiabilityDocument12 pagesVicarious LiabilitySoap MacTavishNo ratings yet

- 9 Measures of Variability DisperseDocument14 pages9 Measures of Variability DisperseSourabh ChavanNo ratings yet

- 9th Science Mcqs PTB PDFDocument25 pages9th Science Mcqs PTB PDFUmar JuttNo ratings yet

- STELEX PrO (E) FinalDocument4 pagesSTELEX PrO (E) FinalGhita-Mehedintu GheorgheNo ratings yet

- MSDS TriacetinDocument4 pagesMSDS TriacetinshishirchemNo ratings yet

- Bending MomentDocument4 pagesBending MomentNicholas TedjasukmanaNo ratings yet

- Pink Illustrative Weather Quiz Game PresentationDocument28 pagesPink Illustrative Weather Quiz Game PresentationMark Laurenze MangaNo ratings yet

- The Residents of The British East India Company at Indian Royal Courts, C. 1798-1818Document224 pagesThe Residents of The British East India Company at Indian Royal Courts, C. 1798-1818Ajay_Ramesh_Dh_6124No ratings yet

- National Power Corporation vs. Teresita Diato-Bernal 2Document3 pagesNational Power Corporation vs. Teresita Diato-Bernal 2mickcarpioNo ratings yet

- Quam SingulariDocument2 pagesQuam SingulariMichael WurtzNo ratings yet

- Unit 10 Conic Sections ProjectDocument8 pagesUnit 10 Conic Sections Projectapi-290873974No ratings yet

- THE HOUSE ON ZAPOTE STREET - Lyka PalerDocument11 pagesTHE HOUSE ON ZAPOTE STREET - Lyka PalerDivine Lyka Ordiz PalerNo ratings yet

- En Subject C08Document13 pagesEn Subject C08jmolfigueiraNo ratings yet

- Everyman A Structural Analysis Thomas F. Van LaanDocument12 pagesEveryman A Structural Analysis Thomas F. Van LaanRodrigoCarrilloLopezNo ratings yet

- Window Server 2008 Lab ManualDocument51 pagesWindow Server 2008 Lab ManualpadaukzunNo ratings yet

- Financial Management Notes - Dividend Decision - Dynamic Tutorials and ServicesDocument10 pagesFinancial Management Notes - Dividend Decision - Dynamic Tutorials and Servicessimranarora2007No ratings yet

- BR COREnew Rulebook v1.5 ENG-nobackground-lowDocument40 pagesBR COREnew Rulebook v1.5 ENG-nobackground-lowDavid Miller0% (1)

- Power2 Leading The Way in Two-Stage TurbochargingDocument4 pagesPower2 Leading The Way in Two-Stage TurbochargingМаксим АгеевNo ratings yet

- ASSESSMENTS Module 1 - Cortezano, ZyraDocument1 pageASSESSMENTS Module 1 - Cortezano, ZyraZyra Mae Cortezano100% (1)

- Name of DrugDocument2 pagesName of Drugmonique fajardo100% (1)

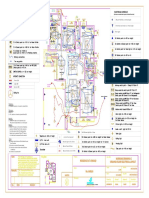

- Varun Valanjeri Electrical Layout-3Document1 pageVarun Valanjeri Electrical Layout-3ANOOP R NAIRNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 The Life of Jose Rizal PDFDocument11 pagesChapter 3 The Life of Jose Rizal PDFMelanie CaplayaNo ratings yet

- Advertising and Imc Principles and Practice 11th Edition Moriarty Solutions ManualDocument28 pagesAdvertising and Imc Principles and Practice 11th Edition Moriarty Solutions Manualcemeteryliana.9afku100% (19)

- Quiz On Digestive SystemDocument2 pagesQuiz On Digestive Systemacademic purposesNo ratings yet

- The BarographDocument8 pagesThe BarographNazre ShahbazNo ratings yet

- Route StructureDocument3 pagesRoute StructureAndrei Gideon ReyesNo ratings yet

- Seniors Playing Record Nov 20 To Dec 2021 New SystemDocument6 pagesSeniors Playing Record Nov 20 To Dec 2021 New Systemapi-313355217No ratings yet