Professional Documents

Culture Documents

SAHANZ Proceedings Examines History of MLC Buildings in Sydney's Martin Place

Uploaded by

Achraf ToumiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

SAHANZ Proceedings Examines History of MLC Buildings in Sydney's Martin Place

Uploaded by

Achraf ToumiCopyright:

Available Formats

Proceedings of the

Society of Architectural Historians

Australia and New Zealand

Vol. 32

Edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan

Published in Sydney, Australia, by SAHANZ, 2015

ISBN: 978 0 646 94298 8

The bibliographic citation for this paper is:

Margalit, Harry, and Paola Favaro. “From Social Role to Urban

Significance: The Changing Presence of the MLC Company

in Martin Place.” In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural

Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 32, Architecture, Institutions

and Change, edited by Paul Hogben and Judith O’Callaghan, 378-

389. Sydney: SAHANZ, 2015.

All efforts have been undertaken to ensure that authors have

secured appropriate permissions to reproduce the images

illustrating individual contributions. Interested parties may

contact the editors.

Harry Margalit and Paola Favaro, UNSW Australia

From Social Role to Urban Significance: The Changing

Presence of the MLC Company in Martin Place

The intersection of Martin Place and Castlereagh Street in Sydney is dominated by a

single institution – the MLC (Mutual Life and Citizens’ Assurance Company). To the

south is the MLC Centre (1971-77), and on the northern corner stands the interwar

MLC building of 1938. The company has a long association with the area, with the

Citizens’ Life Assurance Company established in 1886 and headquartered at 21-25

Castlereagh Street. The MLC Company came into being in 1908 with the amalgamation

of the Citizens’ Life Assurance Co. Limited and the Mutual Life Assurance Association

of Australia.

This paper examines the history of the 1938 and 1977 buildings as a means to

understanding and elucidating not only the development of the company, but also

changing attitudes to how it represented itself through specific buildings, and how the

function and public presence of each building chart a shift in urban design attitudes and

the use of public space. The 1938 building, designed by Bates, Smart & McCutcheon, is

built to the street alignment and holds a host of distinctive details within an Egyptianate

interwar iconography. The 1977 MLC Centre, designed by Harry Seidler & Associates,

presents a significantly altered architectural presence, urban significance and public

accessibility. The paper will be framed around a number of key questions. How did

the 1938 building represent the institution and the presence of capital generally? How

was the MLC Centre pivotal in defining urban strategies for Martin Place that diverged

so significantly from the interwar model? The paper will look not only at the urban

significance of these transformations, but also at the development model that brought

together the MLC Company, the Lend Lease Corporation and Harry Seidler to develop

this part of Sydney as a ‘city for the people’, as the project was termed. The story of the

MLC Company can thus be told not only through its social role asserting the company

as an ‘institution’ for the people, but also in its urban role in creating a ‘place’ for the

people.

378 | SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings

Institution

The history of life insurance is intricately bound up with the development of both mercantile

and industrial capital. The beginning of modern life insurance is conventionally dated

from the establishment of the Society for Equitable Insurance on Lives and Survivorship

in England in 1762. The growth of the industry in Australia in the nineteenth century is a

reflection of the tenuous dependence on wage labour that was the lot of most workers,

and very early in its history the industry came to acquire a moral basis as a form of self-

sustaining charity. In 1977 the historian of the industry in Australia, A. C. Gray, wrote that

“life insurance, even today, is still inspired by a lofty idealism which includes a regard for the

institution of life insurance as being an instrument for social betterment.”1

The institution was thus distinct from banking both on account of its perceived moral

standing and it’s day-to-day functioning. The credit boom of the 1920s saw a swelling of

deposits in banks, whereas the post-crash years saw significant reductions in bank deposits

as a consequence of both unemployment and asset devaluation. By contrast, the value of

assets held by the life insurance companies grew steadily through the Depression, reflecting

the constant stream of money from premiums available for investment. Consequently the

life insurance companies capitalised on their strong income stream by undertaking a highly

visible program of building in the 1930s.

The Mutual Life and Citizens Assurance Company limited, known as the MLC, came into

being in 1907 with the amalgamation of the Citizens’ Life Assurance Co. Limited and the

Mutual Life Assurance Association of Australia (est. 1869), with Martin Place holding a

special place for the institution. Currently, MLC buildings dominate the intersection of Martin

Place and Castlereagh Street. To the south is the MLC Centre (1971-77), and on the northern

corner stands the interwar MLC building of 1938. The northern corner site saw more than

one institutional building erected and re-developed in the span of 150 years. In 1887, the

first office of the Citizen’s Life Assurance Company was established in a five section-terrace

named Black’s Terrace, after the first owner. It was located in Castlereagh Street not far from

what at the time was called Moore Street, until a fire in October 1890 severely damaged two

of the five sections.2 After the decision was taken to demolish the two terraces and widen

Moore Street, the remaining three terraces owned by the MLC Company became a corner

lot between Castlereagh Street and Martin Place.

In 1899 Black’s Terrace was replaced by a French Renaissance tower of six floors that was

demolished for the present 1938 MLC building.3

The design of the 1938 MLC Building was a much more public process than either of the

previous examples, the commission being awarded through a design competition. The

winning design, by the Melbourne firm of Bates, Smart & McCutcheon, is substantially the

same as the built design, and the report which accompanied the competition entry gives

rise to some interesting insights into the design constraints as interpreted by the architects.4

SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings | 379

Harry Margalit and Paola Favaro | From Social Role to Urban Significance: The Changing

Presence of the MLC Company in Martin Place

The bulk of the report, understandably, is argued along strictly rational commercial lines. A

summary of the design intent makes this point unambiguously:

The solution presented by the authors aims at the production of a plan in which

the maximum exploitation of the very valuable site is obtained. An attempt

has been made to obtain the highest possible revenue production, although

maximum area of floor space has been sacrificed where lighting and other

considerations suggested that higher rents for better quality space would be

obtained. In other words the object has been to provide a reasonable maximum

of floor area possessing good lighting, flexibility and general attractiveness.5

Fig. 1 Bates, Smart & McCutcheon, MLC

Building, 1938. Photograph by Sam Hood.

State Library of NSW.

Fig. 2 Second Place Design, Scarborough, Fig. 3 Third Place Design, Andrews and

Robinson & Love, 1936. From Architecture Hawden architects in collaboration, 1936. From

26, no. 2 (February 1937): 36. Architecture 26, no. 2 (February 1937): 38.

380 | SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings

The plans of the various levels reveal a clearly organised office layout, along principles

still current. On a typical office floor the toilets and services are placed at the far end of the

building, along a wall fronting an adjoining site. Should development of the adjoining site shut

out light and ventilation, the toilets simply convert to artificial light and air-conditioning. The

lift shafts and stairs are located at an internal elbow of the “U”-shaped design, in a position

dictated by the location of the main entry and the logical subdivision of the upper floors. The

reason for the selection of the proposal over the second (Scarborough, Robinson & Love

architects) and third (Andrews and Hawden architects in collaboration) placed designs is

evident from their plans; neither came to terms with the preferred entry from Martin Place,

away from the centre of the building. Both responded with two entries of equal importance,

one from Martin Place and one from Castlereagh Street, an ambivalent solution which

confused the ground floor organisation. In the winning design the secondary Castlereagh

Street entry is provided as a matter of convenience and connects to the corridor system in a

straight-forward manner. The significance of the entry treatment and the lift location lies in the

schematic, rationalised organisation which the final design displayed. The ideal lift position

for the upper floors is weighed up against the necessity to be close to the entry, and the final

location represents a weighted compromise. The symmetry of classicist sensibilities has no

place in this planning; the floors are designed for flexible subdivision with a central corridor,

with columns intruding as little as possible so as not to restrict the possible arrangement of

tenancies.

The same sensibility prevails in the stated intent of the external treatment:

The influence of so-called modern architecture and the current tendency

towards very ample lighting have introduced problems in regard to the external

treatment of buildings. The authors incline to the belief that the best solution for

the present day is found in simple, clean and dignified facades which abandon

any set period or style, but which refrain from the exaggerated examples of

architecture which are labelled to-day as “Modern.”6

This description seems somewhat disingenuous. The Egyptianate detailing, typified in

the classic “hollow and roll” cornice of the penultimate storey as well as the four papyrus

columns on the corner tower and the various rolled cornices both internally and externally,

attest to a consistency of stylistic intent which can hardly be described as abandoning “any

set period or style”. The intent was probably to avoid the, by then, tedious Gothic vs. neo-

Classical debate which had evolved into a clichéd sensibility for the lay appreciation of

architectural styles.

The invention of a mythical Egypt has an idealist dimension with roots in the internal tensions

within Sydney’s modernisation. Egypt is evoked as a mythical site where the contradictions

of modern life achieve a resolution, a repose, which is expressed in the identification of

ancient history with transcendental principles. This very teleology, which sustains a view of

modernity as the cutting face of history as progress, links that modernity to ancient times

by identifying them as the crucible of aesthetic schema that continue to inform national

SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings | 381

Harry Margalit and Paola Favaro | From Social Role to Urban Significance: The Changing

Presence of the MLC Company in Martin Place

identity. The recurrent sculptural motif on the MLC consists of a kneeling figure, modelled on

classical precedents, attempting to break a bundle of bound sticks across its knee. Below

the figure is the motto “Union is Strength”. The bundle of sticks is derived from the Roman

fasces, the rods and axe carried by the lictor in front of the magistrate and representing the

power he embodied. Its revival as a symbol can be found on many Deco buildings in New

York, from the Port Authority to the Federal Office Building.7 Often combined with a martial

eagle (as in the case of the Federal Office Building), its identification with other interwar

nationalisms is embodied in the term Fascism. Its use is more circumspect in the MLC,

embodying a basic parable whereby the combined resilience of many through mutual funds

means that the individual cannot be broken, presumably by fate, death or misfortune.

MLC after the war

With the first issue published in June 1957, this section of the paper examines how the MLC

News, the company’s magazine, promoted the role of architecture in projecting the image

of the company as a progressive insurance institution. Each monthly issue included a short

message from the Company or the State General Manager, and other articles related to

items of interest in Australian and overseas history, geography, science and sport all written

by MLC employees. Needless to say, the reading is both informative and entertaining as it

sketches the interests and social life of people in corporate Australia in that period. Essentially

it is a journal written by company staff for policy-holders insured with the company. In the

period leading to the construction of the 1977 MLC Centre a number of articles were written

around the themes of architecture and the architects the company employed for its Sydney

buildings, all displaying the respect – almost a reverence – the company entertained for

Martin Place.

With the title “Our Architects”8, a brief note in the first issue identifies the architects Bates,

Smart & McCutcheon as a privileged firm and an almost historical constant in the institution’s

affairs from the 1936 winning competition entry in Martin Place onwards. The article explains

how the architects had been engaged not only for the new Head Office in North Sydney,

completed in the same year, but also for other MLC buildings to be realised in Brisbane,

Adelaide, Perth, Newcastle, Wollongong, Ballarat, Geelong and Canberra. Between 1952

and 1958 the company was engaged in a prolific building program of an “unprecedented

scale in Australia.”9 New trends in building, planning and lightweight construction methods

were adopted by Bates, Smart & McCutcheon after research and work experience conducted

in the New York architectural office of Skidmore Owings and Merrill (SOM) by senior partner

Osborn McCutcheon.10 The North American influence is evident in the diverse attitude

employed in the design of the 1957 MLC building in North Sydney, with a glazed lightweight

steel frame construction, in comparison to the solid stone-faced 1938 MLC building from the

same firm just two decades earlier.

In September 1957, the new Head Office in North Sydney opened to the evident pride of the

MLC General Manager, who wrote:

382 | SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings

In my recent visit to the United States I saw nothing better than it both

functionally and aesthetically. The building has received much praise from

the many prominent people who have visited it in recent weeks including the

Prime Minister Robert Menzies, who performed the opening ceremony.11

He continues to laud the building not only for the new architectural expression it displayed

but also for its role in initiating new office buildings across the harbor in the suburbs of North

Sydney: “No other office block in Australia and New Zealand has ever received as much

attention from newspapers, radio and television.” 12 The brief article explains how the Board

decided that the existing 1938 building on the corner of Martin Place and Castlereagh Street

was becoming too small to house both the Head Office and the New South Wales Branch,

and it was impossible to expand the existing premises in Martin Place. The move was seen

as a catalyst to establishing North Sydney as a second business centre in the Sydney

Metropolitan Area with the wish to “… perhaps even establish a twin city in the course of

time.”13 The 1957 MLC building was the result of an acquisition of different lots in Miller Street

from different landowners as well as 35 titleholders involved in a deceased estate. This

served as a precedent for the amalgamation of the MLC Centre site in Martin Place.

The same enthusiasm for modern architectural expression evident in the North Sydney

offices was invested in the later MLC Centre. In the 1971 January issue of the MLC News

attention is drawn for the first time to the proposed MLC and the Lend Lease Corporation

development in Martin Place:

The august company of buildings in Martin Place can in a few years expect to

welcome a dramatic new development which is being planned by the MLC and

the Lend Lease Corporation. It is likely to involve most of the block opposite

our Sydney Office and bounded by Martin Place, Pitt, King and Castlereagh

Streets, but excluding the Commonwealth Site. Contemplated is a vast open

pedestrian plaza and the loftiest tower building in Australia, rising to 860 feet

above street level.14

The 1977 MLC Centre

The MLC Centre in Sydney’s CBD occupies a large site of 0.8 hectares, bordered by Martin

Place, Castlereagh Street and King Street. The dominant element of the development is the

office tower of 67 floors, to a total height of 228 metres. The project commenced in 1970

with the amalgamation of 23 individual properties, including the old Hotel Australia, the

Theatre Royal and, in 1973, the Commercial Travellers’ Association Club. It also absorbed

the narrow internal lane of Rowe Street that was exchanged for private land in order to

extend Lee’s Court. The main planning constraint was the existence of the Eastern Suburbs

Railway tunnels running diagonally under the site. Prior to the granting of the DA15 a number

of options had been canvassed for the site, all guided by specific economic criteria.

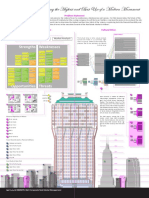

The dominant tower was originally conceived by Seidler in 1970 as a single concrete

structure, over 1,000 feet (305m) high. It was designed with a varying profile to accommodate

SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings | 383

Harry Margalit and Paola Favaro | From Social Role to Urban Significance: The Changing

Presence of the MLC Company in Martin Place

an international standard hotel with shallow areas for hotel rooms on the lower part, and

increased floor area for office space on upper floors, thereby generating a flared form or

‘waisted lady’ shaped tower. A later proposal envisaged two similarly shaped towers.16

Fig. 4 Hotel and Office Tower, 1970. Photograph by Max Dupain.

Courtesy of Harry Seidler & Associates.

A separate 1969 proposal titled City Centre Planning by Harry Seidler & Associates provided

for a series of buildings that fronted a larger area of Martin Place from Castlereagh Street

to York Street, with a tower standing as a gateway across Martin Place on George Street.

Seidler utilised this sketch design to test urban redevelopment thinking, retaining Barnet’s

General Post Office while proposing six towers with a layer of plazas and pedestrian routes

at different levels. This would “determine the mutually beneficial relationship and possible

connection of privately developed office towers covering only 25% of the site. The spaces

between them become valuable assets not only for their own, but the public’s benefit.”17 Max

Fig. 5 City Centre Planning, 1969. Photograph by Max Dupain.

Courtesy of Harry Seidler & Associates.

384 | SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings

Dupain captured the scale models of this proposal, which were described as a “futuristic”

interpretation of this part of the Civic Centre with “pedestrian decks raised above existing

street.”18 The urban agenda and the proposed public benefit of this earlier scheme are

Seidler’s prelude to the MLC Centre as a “city for the people”.

Ultimately, the scheme with a single tower where a series of shopping arcades, a private

club and a new Theatre Royal replaced the amalgamated properties was selected due to

its economic viability and future commercial potential. A compromise with the authorities

allowed the architect and the developer, Gerardus Jozef ‘Dick’ Dusseldorp, to increase the

floor space index to 15 times the site area, but occupying only 25 per cent of the site.

As Seidler recalled:

Throughout the design period, the fundamental planning aim became clearer,

namely to create an urban focal point containing large spaces for the enjoyment

of people in the centre of the city, with open plazas, areas of repose, artworks,

outdoor restaurants, trees, etc., all in conjunction with a major commercial

development of offices, a theatre, shopping areas and a multitude of other

uses.19

Fig. 6 MLC Centre, 1977. Photograph by Max Dupain.

Courtesy of Harry Seidler & Associates.

Seidler’s capacity not only as a significant commercial architect but also as an urban designer

became evident as early as 1956 with a proposal for a McMahons Point Redevelopment scheme

in North Sydney. Seidler, alongside a group of architects and planners involved in the project,

presented a landmark re-development study proposal, Urban Redevelopment Concerns

You! Ultimately this proposal failed, apart from isolated gestures such as Seidler’s Blues

Point Tower, completed in 1962. A series of realised and unrealised projects and competition

schemes develops Seidler’s urbanistic stance, from the competition entry for the Sydney Cove

Redevelopment Authority in The Rocks (1962) to the Australia Square Tower (1958-67), winner

of both the John Sulman medal and the Civic Design award from the RAIA in 1967.

SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings | 385

Harry Margalit and Paola Favaro | From Social Role to Urban Significance: The Changing

Presence of the MLC Company in Martin Place

Australia Square can rightly be seen as a critical precedent to the MLC Centre. It initiated

a series of urban design propositions and technological innovations, which were further

elaborated in the design for the MLC Centre. Indeed the MLC Centre can be viewed as

Seidler’s proposition for an optimal form of urban redevelopment, public realm reconfiguration

and financial viability. This builds on his evident interest in broader urban issues through

institutions such as Denis Winston’s Planning Research Institute, hosted at the University of

Sydney. Seidler’s design, confronting a number of architectural and construction problems,

expressed the inherent potential of reinforced and pre-stressed concrete, elegantly defining

an urban composition standing across from the earlier interwar MLC Building.

While the 1938 MLC building transcends classical antecedents through the adoption of

the Egyptianate style, in the 1970s MLC centre the influence of a rationalist Modernism

becomes evident. The solution for the MLC Centre tower utilises a plan and section informed

by a sophisticated structural system designed in consultation with the Italian engineer Pier

Luigi Nervi. The octagonal geometry of the floor plan, with its unequal sides, is organised

around efficient utilisation of the access core. A layout typical of the utilitarian concept for

an office high-rise tower is given tectonic strength through eight massive concrete columns,

which taper from bottom to top to accommodate the change of stress and load. As Seidler’s

comments:

But such tall structures with the benefit of consultants such as Nervi, are given

expressive form and this means for a tall building to show the fact that it needs

to be more rigid at the bottom than at the top. One can see here by the way

the columns at the bottom of the building become larger and in fact change

position and change their shape, facing outward, making the building more

rigid at the base as the laws of nature demand it to be.20

The structural scheme of the columns is tied to the core by a rigid system of exposed

interlocking beams, and the façade is aesthetically toned by the expressive form of the long

span I-shaped spandrel beams.

The office layout changes from a typical design of a sequential series of individual rooms

around the perimeter of the tower with meeting rooms, public and service spaces in the

inner part to a more flexible layout of open spaces spanning one, two or three levels and

connected by sculptural stairs in large tenancies. As Frampton and others have noted,

Seidler draws on modern art and rationalist structure and his adoption of “curvilinear mass

that governs his public works” creates his instructive exemplars of the “tectonics of concrete

constructions”.21

Seidler’s MLC Centre and Australia Square can be considered as significant examples of

transformative urban architecture in Sydney’s post-war city planning. By the beginning of the

1970s Sydney had absorbed the urban proposition of Australia Square. Nevertheless city

authorities remained more comfortable with respecting street alignments and the compact

and consistent massing of the interwar city rather than the variations of volumes, set-backs

and open space of Seidler’s palette.

386 | SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings

The suggestion here is that the combination of two established institutions such as the

MLC and Lend Lease Corporation, the professional figures of Seidler and Nervi and

progressive city planning instruments such as the 1971 City of Sydney Strategic Plan22

made this urban project possible. Seidler’s relationship with Dick Dusseldorp, a Dutch

engineer and managing director of Civil & Civic Contractors (founded in 1951, later Lend

Lease Corporation) commenced with the design for Ithaca Gardens in Elizabeth Bay (1959-

60), followed by Blues Point Tower in North Sydney (1962).23 But the realisation of the MLC

Centre is the result of a strong working relationship not only between developer and architect

but also between the developer Dusseldorp, acting through Lend Lease, and the MLC

Insurance Company, led at the time by CEO Milton Allen. This is made explicit in a recent

publication that documents how the MLC had been a major investor in Lend Lease since its

beginnings in 1958, and the MLC had written most of Lend Lease’s Insurance Policies since

the company was formed.24 Both Lend Lease and the MLC initiated buying properties on

the site of the MLC Centre, with the major purchases made in 1969 and 1970. In September

1969, Dusseldorp bought the historic Theatre Royal at auction for $7.25 million, described in

a local newspaper as the “biggest single real estate sale in Australia.”25 One year later Milton

Allen put down $960,000 as the deposit for the $9.6 million sale price for the purchase of the

historic Australia Hotel.26 MLC and Lend Lease are mentioned in a newspaper article in early

1970 as the owner and developer respectively for the proposed Martin Place Plaza Block.

The MLC Centre was completed in 1977, but as early as 1974 a piece in Constructional

Review titled, “City for the People” makes explicit the shift the project represented towards

private, but civic, space:

The intention is to create a centre where people can enjoy themselves in the

centre of the city. It will have open plazas, areas of repose, outdoor restaurants,

and areas shaded by trees all in conjunction with a major commercial

development comprising offices, a theatre, cinema, taverns, shopping areas,

parking, etc.27

With photographs by Max Dupain, the article continues: “The resulting privately owned land,

given over to permanent public use will create a much needed sense of spaciousness in a

previously congested part of the city.” In 1980 Builder published an article celebrating the

public areas as a “natural extension of the Martin Place pedestrian space.”28

Conclusion

Although only 30 years separate the construction of the MLC building of 1938 and the

genesis of the post-war MLC Centre across Martin Place, the historical gulf between the

two seems like an epoch. It is not simply that the one was built prior to the Second World

War and the other some years after, but also that they represent major shifts in ideas of the

city, in the economics of major city buildings and in the iconography or symbolic content

of different ways of building. The simple urban paradigm of building to the street alignment

in order to maximise site coverage and hence keep building mass low, gives way to a more

SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings | 387

Harry Margalit and Paola Favaro | From Social Role to Urban Significance: The Changing

Presence of the MLC Company in Martin Place

complex massing of building form that makes use of high speed lifts and vastly improved

means of building to substantial heights. The distinction between the public realm and the

private also changes considerably. In the 1938 building the street alignment demarcates the

boundary between the two, and the footpath is the means by which the public moves about

the building. In its successor the public movement around the building is more complex,

and includes the idea that retail justifies the inclusion of public circulation within the confines

of the site.

In construction, too, we see a major shift in architectural representation. While the embedded

symbolism displayed in the 1938 building was soon superseded by both a new, rationalist,

approach to architecture as noted above, as well as by the sensitivity to fascist and martial

symbols brought about by the war itself, new methods of construction also gave rise to

displays of structural virtuosity. The war itself also made other contributions to the later MLC

development. Its events displaced a young but driven resident of Vienna, Harry Seidler, who

found his way to Sydney after the war and became both transmitter of, and advocate for,

a very different development paradigm. This new view of city development was taken up

by an MLC also deeply transformed from a guarantor of family stability to a transformer of

the city itself through its ambitions as a real estate developer. That the institution saw these

ambitions as consonant with the wider public good can be read through its coverage of the

MLC Centre opening:

The opening concentrated attention on a magnificent building and the

surrounding complex but there is a deeper significance. Life Insurance is a

service to the public and MLC is a contributor to that service. As a direct result

of the accumulation of the savings of policy owners, investments in projects

of national importance, be they city buildings, or resource developments, are

made possible. MLC represents the investment of policy-owner funds and

it is clear that hundreds of thousands of Australians should have a sense of

ownership and pride in this exciting new Australian development.29

1 A. C. Gray, Life Insurance in Australia (Melbourne: McCarron Bird, 1977), 6.

2 R. H. Clarke, “The Great Fire of Sydney – October 1890,” MLC News 5, no. 8 (August 1961): 4-10.

3 In 1957 the MLC Head Office was moved to North Sydney in a new building also designed by Bates,

Smart & McCutcheon and the 1938 MLC building remained as the NSW branch.

4 “Mutual Life and Citizens Building, Sydney: Results of Architectural Competition,” Building, 352

(December 1936): 30-36.

5 “New Head Office: Mutual Life and Citizens’ Assurance Co. Ltd., Sydney,” Architecture 26, no. 2

(February 1937): 26.

6 “New Head Office,” 28.

7 Bronwyn Hanna, “Tall Storeys: A History of the Life Insurance Buildings in Sydney” (Fine Arts IV Thesis,

Power Institute, University of Sydney, 1985).

8 MLC News 1, no. 1 (June 1957): 14.

9 Alan Ogg, “MLC Buildings,” in Tall Buildings: Australian Business Going Up: 1945-1970, by Jennifer

Taylor with Susan Stewart et al. (Sydney: Craftsman House, 2001), 165.

10 Ogg, “MLC Buildings,” 166.

388 | SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings

11 MLC News 1, no. 4 (September 1957): 3.

12 MLC News 1, no. 4 (September 1957): 3.

13 MLC News 1, no. 4 (September 1957): 13-21.

14 Claims Officer Jim Horton, MLC News 15, no. 1 (January 1971): 12.

15 Harry Seidler Collection, Register of Drawing Tubes, PXD 613, Mitchell Library.

16 Peter Blake, Architecture for the New World: The Work of Harry Seidler (Sydney and New York: Horwitz

Australia, 1973), 89.

17 Blake, Architecture for the New World, 100-104.

18 Blake, Architecture for the New World, 100-104.

19 Harry Seidler, Planning and Building Down Under: New Settlement Strategy and Current Architectural

Practice in Australia (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1978), 17.

20 Harry Seidler, “Work in the Mainstream of Modern Architectural Development” (lecture, RAIA Sydney

Institute, 1980).

21 Kenneth Frampton, “Isostatic Architecture,” in Harry Seidler: Four Decades of Architecture, ed. Kenneth

Frampton and Philip Drew (London: Thames and Hudson, 1992), 110; Philip Drew, Two Towers. Harry

Seidler: Australia Square, MLC Centre (Sydney: Horwitz Grahame Books, 1980), 7; Gevork Hartoonian,

“Harry Seidler. Revisiting Modernism,” Fabrications 20 no. 1 (2011): 45; Vladimir Belogolovsky, Harry

Seidler LifeWork (New York: Rizzoli, 2014), 11.

22 The Council of the City of Sydney, City of Sydney Strategic Plan (1971).

23 Lindie Clark, Finding a Common Interest: The Story of Dick Dusseldorp and Lend Lease (Cambridge;

Port Melbourne, Vic.: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 125.

24 Val Montagnana-Wallace, MLC (Sydney: Bounce Books on behalf of MLC, 2002), 123.

25 “$7.25m paid for Sydney block,” Canberra Times, September 26, 1969, 8.

26 “Australia Hotel sold for $9.6m,” Canberra Times, February 26, 1970, 31.

27 “City for the People,” Constructional Review (February 1974): 2-15.

28 “MLC Centre,” Builder (NSW) (October 1980): 514-521.

29 MLC News (October 1978): 3.

SAHANZ 2015 Conference Proceedings | 389

You might also like

- Paul Johnson Making The Market Victorian Origins of Corporate Capitalism PDFDocument266 pagesPaul Johnson Making The Market Victorian Origins of Corporate Capitalism PDFAli BabaNo ratings yet

- The Golden Mile Complex - From Architect's Vision To Vertical Slum'Document6 pagesThe Golden Mile Complex - From Architect's Vision To Vertical Slum'Philipp AldrupNo ratings yet

- RFBT ExamsDocument42 pagesRFBT ExamsJoyce LunaNo ratings yet

- Retainer Contract ServicesDocument2 pagesRetainer Contract ServicesAileen GaviolaNo ratings yet

- EVE Chapter 8Document42 pagesEVE Chapter 8Erickah PerladoNo ratings yet

- The Thick 2d - Stan Allen PDFDocument22 pagesThe Thick 2d - Stan Allen PDFGuadaNo ratings yet

- TD Centre Project Final2Document23 pagesTD Centre Project Final2api-272637600No ratings yet

- The Resurgence of High-Rise Living in LondonDocument30 pagesThe Resurgence of High-Rise Living in Londoncarl2005No ratings yet

- Mega Projects in New York London and AmsterdamDocument18 pagesMega Projects in New York London and Amsterdam1mirafloresNo ratings yet

- Week 3 ModuleDocument14 pagesWeek 3 ModuleSofia Biangca M. BalderasNo ratings yet

- Compendium For Civic The EconomyDocument203 pagesCompendium For Civic The EconomyNesta86% (7)

- Housing For Everyone ArchitectureauDocument5 pagesHousing For Everyone Architectureauapi-312926862No ratings yet

- For Years I Have Been Fed Up With The Kind of Place A Man and A Woman and A Family Should Live In'Document17 pagesFor Years I Have Been Fed Up With The Kind of Place A Man and A Woman and A Family Should Live In'Konstantilenia KoulouriNo ratings yet

- Emergency Relief: Occupied Exhibition Review by Michael BojkowskiDocument20 pagesEmergency Relief: Occupied Exhibition Review by Michael BojkowskiMichael BojkowskiNo ratings yet

- City Beautiful & Broadacre City Planning MovementsDocument20 pagesCity Beautiful & Broadacre City Planning MovementsajNo ratings yet

- Byker StateDocument10 pagesByker StateTOPAtankNo ratings yet

- Citicorp ReexaminedDocument9 pagesCiticorp Reexamined115 - Christine YulianaNo ratings yet

- John Summerson examines changing attitudes in architecture between 1925-1938Document12 pagesJohn Summerson examines changing attitudes in architecture between 1925-1938Dely BentesNo ratings yet

- The Property Development Process Case Studies From Grainger TownDocument18 pagesThe Property Development Process Case Studies From Grainger TownDung TrinhNo ratings yet

- Designing-Playspaces-For-The-Emerging-Society-Of-Car-Owners-In-Post-War-Council-Housing-In-Britain - Content File PDFDocument17 pagesDesigning-Playspaces-For-The-Emerging-Society-Of-Car-Owners-In-Post-War-Council-Housing-In-Britain - Content File PDFIoana INo ratings yet

- Heritage and Preservation of Modern ArchitectureDocument9 pagesHeritage and Preservation of Modern Architecturehih221142No ratings yet

- Architecture ManagementDocument12 pagesArchitecture ManagementBUDIONGAN, GUINDELYNNo ratings yet

- Seagram BuildingDocument16 pagesSeagram BuildingJuan Felipe ManriqueNo ratings yet

- Aesthetics of Industrial Architecture inDocument9 pagesAesthetics of Industrial Architecture inshe_eps9181No ratings yet

- Modern Architectures in the Gilded AgeDocument35 pagesModern Architectures in the Gilded AgeSnehal JainNo ratings yet

- Vivek Shastry - December 4, 2013 Moon Towers: Towards Adaptive Reuse I. RecapDocument3 pagesVivek Shastry - December 4, 2013 Moon Towers: Towards Adaptive Reuse I. RecapsvivekshastryNo ratings yet

- Urban Development Corporations-LibreDocument10 pagesUrban Development Corporations-LibremanoelnascimentoNo ratings yet

- The Speculative Builders and Developers of Victorian LondonDocument51 pagesThe Speculative Builders and Developers of Victorian LondonGergő HegedüsNo ratings yet

- Urban SprawlDocument3 pagesUrban SprawlJohnDominicMoralesNo ratings yet

- The Quiet Revolution in British Housing - Art and Design - The GuardianDocument9 pagesThe Quiet Revolution in British Housing - Art and Design - The GuardianpllssdsdNo ratings yet

- Iconic Architecture in Globalizing Cities: International Critical Thought September 2012Document17 pagesIconic Architecture in Globalizing Cities: International Critical Thought September 2012Milenia NakitaNo ratings yet

- Megastructure PPfor ResearchgateDocument34 pagesMegastructure PPfor Researchgatelianlongl1121No ratings yet

- CR Hs 23071 7 12 Bartholomew Road Birmingham Brochure 4 - HistoryDocument57 pagesCR Hs 23071 7 12 Bartholomew Road Birmingham Brochure 4 - Historyapi-280376343No ratings yet

- Forgotten Spaces Rejuvenation IdeasDocument8 pagesForgotten Spaces Rejuvenation IdeasAalaa ZaNo ratings yet

- Corviale Web PDFDocument20 pagesCorviale Web PDFyuchenNo ratings yet

- Badan Warisan - Buletin Warisan Dec 2004Document16 pagesBadan Warisan - Buletin Warisan Dec 2004RemyFaridNo ratings yet

- ArchitectureeDocument6 pagesArchitectureeHiledeNo ratings yet

- UDT Final A4 Full Bleed.Document62 pagesUDT Final A4 Full Bleed.jonnyballardNo ratings yet

- Ctbuh Technical Paper: Tree House Residence Hall, BostonDocument9 pagesCtbuh Technical Paper: Tree House Residence Hall, BostonbansaldhruvNo ratings yet

- 2 2 BluestoneDocument24 pages2 2 BluestoneMarius MicuNo ratings yet

- Garden City of Tommorrow: Ebenezer HowardDocument23 pagesGarden City of Tommorrow: Ebenezer Howarderika maanoNo ratings yet

- Urban Design Strategies Help Revitalize Brixton Town CentreDocument2 pagesUrban Design Strategies Help Revitalize Brixton Town CentremmhathNo ratings yet

- UK tall building policy ensures quality designDocument22 pagesUK tall building policy ensures quality designjasareNo ratings yet

- Town Planning According To Artistic Principles The American VitrulliusDocument10 pagesTown Planning According To Artistic Principles The American VitrulliuskautukNo ratings yet

- Presentation BookDocument30 pagesPresentation BookCarla Olukemi SchleicherNo ratings yet

- Legislating For EnthusiasmDocument6 pagesLegislating For EnthusiasmtaneruskupluNo ratings yet

- The Collective PortfolioDocument28 pagesThe Collective PortfoliodoliamahakNo ratings yet

- The Adaptive Reuse of Historic Industrial Buildings: Regulation Barriers, Best Practices and Case StudiesDocument40 pagesThe Adaptive Reuse of Historic Industrial Buildings: Regulation Barriers, Best Practices and Case StudiesAndrei NedelcuNo ratings yet

- Precedent Case StudyDocument8 pagesPrecedent Case StudyPriti Shukla0% (1)

- Marina City: Iconic Urban Renewal ProjectDocument54 pagesMarina City: Iconic Urban Renewal ProjectSebastian VillarrealNo ratings yet

- Eliot S Insight The Future of Urban DesignDocument5 pagesEliot S Insight The Future of Urban DesignPrudhvi Nagasaikumar RaviNo ratings yet

- Failure of 'Housing' Concept in 1960sDocument9 pagesFailure of 'Housing' Concept in 1960sfannkoNo ratings yet

- Detroit - The Fall of The Public Realm: The Street Network and Its Social and Economic Dimensions From 1796 To The PresentDocument24 pagesDetroit - The Fall of The Public Realm: The Street Network and Its Social and Economic Dimensions From 1796 To The PresentcentralparkersNo ratings yet

- 06march13simonthurley PostwararchitectureDocument7 pages06march13simonthurley PostwararchitectureAnna Lintu DiaconuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Summary, Important Notes, Key Notes, Q ADocument7 pagesChapter 5 Summary, Important Notes, Key Notes, Q AWaqasAliKhan1No ratings yet

- A Tale of Two City HallsDocument10 pagesA Tale of Two City HallsMădălinaAstancăiNo ratings yet

- Neither Shoreditch Nor Manhattan. Black Country Creative Advantage.Document120 pagesNeither Shoreditch Nor Manhattan. Black Country Creative Advantage.Vykoukalová Mon IkaNo ratings yet

- DR ReportDocument72 pagesDR ReportGosia StarzynskaNo ratings yet

- Temenos, C., Baker, T., Cook, I. (2019) Mobile Urbanism. Cities and Policy MobilitiesDocument25 pagesTemenos, C., Baker, T., Cook, I. (2019) Mobile Urbanism. Cities and Policy MobilitiesJoão Alcantara de FreitasNo ratings yet

- Planning - Urban Exploration and DerelictionDocument11 pagesPlanning - Urban Exploration and DerelictionGraham O'BrienNo ratings yet

- 19 Paola FavaroDocument13 pages19 Paola FavaroAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- "Inevitably Translated" - Pier Luigi Nervi's Work in AustraliaDocument14 pages"Inevitably Translated" - Pier Luigi Nervi's Work in AustraliaAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Guerzoni Nuccio 2013JCEDocument28 pagesGuerzoni Nuccio 2013JCEAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Committee For North Sydney Re MLC Building Aug2020 01 3Document3 pagesCommittee For North Sydney Re MLC Building Aug2020 01 3Achraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Construction of Toll Station Building On The HighwayDocument10 pagesConstruction of Toll Station Building On The HighwayAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Urban Design in Central Sydney 1945-2002: Exploring Laissez-Faire and Discretionary TraditionsDocument150 pagesUrban Design in Central Sydney 1945-2002: Exploring Laissez-Faire and Discretionary TraditionsAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- The Architecture and The City of Aldo Rossi, 1955-1969: The Analogical Locus Vs Ambientalismo of The Building FabricDocument46 pagesThe Architecture and The City of Aldo Rossi, 1955-1969: The Analogical Locus Vs Ambientalismo of The Building FabricAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- NR & New International Selection Documentation Minimum FicheDocument11 pagesNR & New International Selection Documentation Minimum FicheAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Pier Luigi Nervi and Harry Seidler's Australia Square TowerDocument27 pagesPier Luigi Nervi and Harry Seidler's Australia Square TowerAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Pier Luigi Nervi's Structural Works Face Preservation ChallengesDocument12 pagesPier Luigi Nervi's Structural Works Face Preservation ChallengesAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Torre Velasca - Determining The Highest and Best Use of A Modern MonumentDocument1 pageTorre Velasca - Determining The Highest and Best Use of A Modern MonumentAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Living in architectural icon Velasca Tower in heart of MilanDocument13 pagesLiving in architectural icon Velasca Tower in heart of MilanAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Milan 1945, The Reconstruction - Modernity, Tradition, ContinuityDocument10 pagesMilan 1945, The Reconstruction - Modernity, Tradition, ContinuityAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Tall Buildings in MilanoDocument17 pagesTall Buildings in MilanoAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Determination of The Neutralization Depth of Concrete Under The Aggressive Environment InfluenceDocument5 pagesDetermination of The Neutralization Depth of Concrete Under The Aggressive Environment InfluenceAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Adrian Sheppard in Conversation With Antonella MarziDocument20 pagesAdrian Sheppard in Conversation With Antonella MarziAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Pier Luigi Nervi Vs Fazlur Khan - The Developing of The Outrigger System For Skyscrapers PDFDocument10 pagesPier Luigi Nervi Vs Fazlur Khan - The Developing of The Outrigger System For Skyscrapers PDFAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- High Rise Buildings in Europe From Energy Performance PerspectiveDocument7 pagesHigh Rise Buildings in Europe From Energy Performance PerspectiveAchraf ToumiNo ratings yet

- Through History and Technique Pier Luigi Nervi On PDFDocument13 pagesThrough History and Technique Pier Luigi Nervi On PDFAntônio CarotiniNo ratings yet

- Job Application Letter Internal Vacancy SampleDocument8 pagesJob Application Letter Internal Vacancy Sampleafdlxeqbk100% (1)

- Commercial Law Case Digest: List of CasesDocument57 pagesCommercial Law Case Digest: List of CasesJean Mary AutoNo ratings yet

- Principles of Engineering EconomyDocument14 pagesPrinciples of Engineering Economyabhilash gowdaNo ratings yet

- Final Propsal 3Document63 pagesFinal Propsal 3hinsene begna100% (1)

- Annual Report 2020-21Document121 pagesAnnual Report 2020-21Chhavi GajnaniNo ratings yet

- CIR v. PDI (Waiver)Document30 pagesCIR v. PDI (Waiver)Jerwin DaveNo ratings yet

- SYZ Mining Audit Problem AnalysisDocument26 pagesSYZ Mining Audit Problem AnalysisKate NuevaNo ratings yet

- The Emirates Palace - Abu DhabiDocument34 pagesThe Emirates Palace - Abu DhabiShakti ShivanandNo ratings yet

- OCD-LGU MOA for Isolation Facility ConstructionDocument8 pagesOCD-LGU MOA for Isolation Facility ConstructionORLANDO GIL FAJICULAY FAJARILLO Jr.No ratings yet

- Firming Up Inequality: How Rising Between-Firm Dispersion Contributed to Rising U.S. Earnings InequalityDocument50 pagesFirming Up Inequality: How Rising Between-Firm Dispersion Contributed to Rising U.S. Earnings InequalitySiti Nur AqilahNo ratings yet

- FX Factsheet Leveraged Forward enDocument2 pagesFX Factsheet Leveraged Forward enPiyushKumarNo ratings yet

- NPD ReportDocument14 pagesNPD ReportHidayah AzizanNo ratings yet

- Ifr-Apc 311Document8 pagesIfr-Apc 311hkndarshanaNo ratings yet

- GW-Solar System Container PDFDocument4 pagesGW-Solar System Container PDFedwardoNo ratings yet

- Pteroleum Economy Exercise - DepreciationDocument31 pagesPteroleum Economy Exercise - Depreciationshaziera omarNo ratings yet

- Selling Groceries Through The Cloud in A Tier II City in IndiaDocument12 pagesSelling Groceries Through The Cloud in A Tier II City in IndiaFathima HeeraNo ratings yet

- Swifts Cable TrayDocument148 pagesSwifts Cable TrayMichael Bou KarimNo ratings yet

- Organization: The Five Trademarks of Agile OrganizationsDocument20 pagesOrganization: The Five Trademarks of Agile OrganizationsAbdelmutalab Ibrahim AbdelrasulNo ratings yet

- PettyferMichaelAKarl 2011 MonopoliesTheoryEffectivenessandRegulatiDocument151 pagesPettyferMichaelAKarl 2011 MonopoliesTheoryEffectivenessandRegulatiAndres IslasNo ratings yet

- Summary of Checks Issued: Sampaguita, Solana, CagayanDocument1 pageSummary of Checks Issued: Sampaguita, Solana, CagayanXian Ase MiguelNo ratings yet

- Vacation Planning and Tour ManagementDocument114 pagesVacation Planning and Tour ManagementDhawal RajNo ratings yet

- Landmark Guide Real Estate Valuation PrinciplesDocument8 pagesLandmark Guide Real Estate Valuation PrinciplesChristopher Gutierrez CalamiongNo ratings yet

- Commentary: Ophthalmic Increasing Operations ofDocument2 pagesCommentary: Ophthalmic Increasing Operations ofDurval SantosNo ratings yet

- PEPSI COLA vs. MolonDocument28 pagesPEPSI COLA vs. MolonChristle CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Substantive Procedures: 1) Trade RecievablesDocument3 pagesSubstantive Procedures: 1) Trade RecievablesMeghaNo ratings yet

- Financial Statements ExercisesDocument3 pagesFinancial Statements ExercisesNaresh Sehdev100% (1)

- Internationalization CanvasDocument1 pageInternationalization CanvasRomulo Alexandre Soares - RASNo ratings yet