Professional Documents

Culture Documents

04.0 PP 1 15 Whither Criminological Theory

Uploaded by

matfernandezOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

04.0 PP 1 15 Whither Criminological Theory

Uploaded by

matfernandezCopyright:

Available Formats

I

Whither criminological theory?

T h e theory in this book s u g g e s t s that the key to crime control is

cultural c o m m i t m e n t s to s h a m i n g in w a y s that I call reintegrative.

Societies w i t h l o w crime rates are those that s h a m e potently and

j u d i c i o u s l y ; i n d i v i d u a l s w h o resort to crime are those insulated from

s h a m e over their w r o n g d o i n g . H o w e v e r , s h a m e c a n be applied

injudiciously a n d counterproductively; the theory seeks to specify

the types o f s h a m i n g w h i c h c a u s e rather than prevent crime.

Toward a General Theory

C r i m e is not a u n i d i m e n s i o n a l construct. For this reason o n e s h o u l d

not be overly o p t i m i s t i c a b o u t a general theory w h i c h sets out to

e x p l a i n all types o f crime. I n fact, until fairly recently, I w a s so

p e s s i m i s t i c a b o u t s u c h a n e n d e a v o r as to regard it as m i s g u i d e d .

Clearly, the kinds of variables required to explain a p h e n o m e n o n

like rape are very different from those necessary to a n e x p l a n a t i o n of

embezzlement.

E q u a l l y clearly, there is a long tradition of purportedly general

theorizing in c r i m i n o l o g y w h i c h in fact offers e x p l a n a t i o n s of m a l e

criminality to the e x c l u s i o n of female crime by focusing totally o n

male socialization experiences as explanatory variables. Other

theories focus o n big city crime to the exclusion of small t o w n a n d

rural crime by alighting u p o n urban e n v i r o n m e n t as an e x p l a n a t i o n ;

others e x p l a i n j u v e n i l e but not adult crime, or neglect the n e e d to

e x p l a i n w h i t e collar crime.

N o t w i t h s t a n d i n g the diversity of b e h a v i o r s u b s u m e d under the

crime rubric, the c o n t e n t i o n of this book is that there is sufficient in

c o m m o n b e t w e e n different types o f crime to render a general ex-

p l a n a t i o n p o s s i b l e . T h i s c o m m o n a l i t y is not inherent in the nature of

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

2 Crime, shame and reintegration

the d i s p a r a t e acts c o n c e r n e d . It arises from the fact that crime,

w h a t e v e r its form, is a kind o f b e h a v i o r w h i c h is poorly regarded in

the c o m m u n i t y c o m p a r e d to m o s t other acts, a n d b e h a v i o r w h e r e

this p o o r regard is institutionalized. Perpetrators o f crime c a n n o t

c o n t i n u e to offend o b l i v i o u s to the institutionalized disapproval

d i r e c t e d at w h a t they d o . U n l i k e l a b e l i n g theorists, I therefore a d o p t

the v i e w that m o s t criminality is a quality of the act; the distinction

b e t w e e n behavior a n d action is that b e h a v i o r is n o m o r e than physical

w h i l e a c t i o n h a s a m e a n i n g that is socially given. ' T h e a w a r e n e s s

that a n action is d e v i a n t f u n d a m e n t a l l y alters the nature o f the

c h o i c e s b e i n g m a d e ' ( T a y l o r et al, 1973: 147).

It h a s b e e n said that there is n o t h i n g inherently d e v i a n t a b o u t

u s i n g a syringe to inject o p i a t e into o n e ' s a r m b e c a u s e doctors d o it

all t h e time in hospitals - d e v i a n t b e h a v i o r is n o m o r e t h a n b e h a v i o r

p e o p l e s o label. H o w e v e r arbitrary the l a b e l i n g process, it is the fact

that t h e criminal c h o o s e s to e n g a g e in the b e h a v i o r k n o w i n g that it

c a n b e s o labeled that d i s t i n g u i s h e s criminal choices from other

c h o i c e s . It is the defiant nature o f the c h o i c e that d i s t i n g u i s h e s it

from other social action.

J i m m y a n d J o h n n y are confronted w i t h a n o p p o r t u n i t y to c o m m i t

crime: a n u n l o c k e d car. J o h n n y feels p a n g s o f c o n s c i e n c e o v e r w h e l m

h i m a s h e a p p r o a c h e s the criminal opportunity; h e also thinks of

h o w a s h a m e d his m o t h e r w o u l d b e if h e were caught; h e backs off.

J i m m y , in contrast, g o e s a h e a d , steals the car, is unlucky e n o u g h to

be c a u g h t , a p p e a r s before a j u d g e , a d m i t s that he h a s c o m m i t t e d a

c r i m e a n d is c o n v i c t e d , a fact a n n o u n c e d in the local n e w s p a p e r . I n

all o f this, J i m m y a n d J o h n n y , J o h n n y ' s m o t h e r , the j u d g e , a n d

t h o s e w h o read the n e w s p a p e r all shared a v i e w o f w h a t crime w a s

a n d w h a t the courts h a v e the authority to d o w h e n criminals are

c a u g h t . T h e r e is n o other w a y for the participants to m a k e sense o f

s u c h interactions w i t h o u t s o m e shared v i e w o f the institutional

orders i n v o l v e d - in this c a s e those o f the criminal l a w a n d the

criminal j u s t i c e s y s t e m . T h e critical point is that b y all o f t h e m

i n v o k i n g the institutional order they h e l p to reproduce it. J i m m y

a n d J o h n n y , their families, the police w h o catch t h e m , their lawyers,

the j u d g e , all treat the criminal l a w a n d the criminal j u s t i c e s y s t e m

as 'real' c o n c e p t s w h i c h define w h a t J i m m y d i d . T h e y are institu-

tional relationships w i t h i n w h i c h the e n c o u n t e r s w i t h t h e police a n d

courts are s i t u a t e d , a n d institutional relationships that are i n d e e d

c o n s t i t u t e d b y interactions s u c h as those e x p e r i e n c e d b y J i m m y .

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Whither criminological theory? 3

T h e criminal l a w a n d the criminal j u s t i c e s y s t e m are Veal' precisely

b e c a u s e c o u n t l e s s p e o p l e like these a c c e p t t h e m as real a n d repro-

d u c e t h e m t h r o u g h s u c h social action.

It is not that, as W . I. T h o m a s (1951:81) said, if actors 'define

situations as real they are real in their c o n s e q u e n c e s ' , b e c a u s e this

f a m o u s d i c t u m i m p l i e s that s o m e t h i n g like crime m i g h t not be real:

it o n l y has c o n s e q u e n c e s b e c a u s e p e o p l e believe in it. Rather, crime

is r e p r o d u c e d as s o m e t h i n g real by repeated s e q u e n c e s of interac-

tions akin to those o f J i m m y a n d J o h n n y . Similarly, s h a m e , consci-

e n c e , the p o w e r and authority of the police and the j u d g e - the

things that c o n s t r a i n e d J o h n n y but not J i m m y - are structural and

p s y c h o l o g i c a l constraints u p o n crime w h i c h are t h e m s e l v e s repro-

d u c e d as real by the very e n c o u n t e r s in w h i c h the crime construct is

r e p r o d u c e d . Social structures like the criminal j u s t i c e s y s t e m are

therefore b o t h a resource for actors to m a k e sense of their action and

a p r o d u c t of that action; social structure is reproduced as an objec-

tive reality that partially constrains the very kinds of actions w h i c h

constitute it ( G i d d e n s , 1984).

A theory of a n y topic X will be a n i m p l a u s i b l e idea unless there is

a prior a s s u m p t i o n that X is of w h a t Philip Pettit (pers. c o m m . ,

1986) calls a n e x p l a n a n d a r y kind. T o be an e x p l a n a n d a r y kind, X

n e e d not be fully h o m o g e n e o u s , only sufficiently h o m o g e n e o u s for it

to be likely that every type or m o s t types of X will c o m e under the

s a m e causal influences. T h e r e is n o w a y of k n o w i n g that a class of

actions is of a n e x p l a n a n d a r y kind short of a plausible theory of the

class b e i n g d e v e l o p e d . In a d v a n c e , giraffes, clover and n e w t s m i g h t

s e e m a h e t e r o g e n o u s class, yet the theory of evolution s h o w s h o w the

proof of the p u d d i n g is in the eating. A general theory is not required

to e x p l a i n all of the v a r i a n c e for all types of cases, but s o m e of the

v a r i a n c e for all types of cases.

T h e h o m o g e n e i t y p r e s u m e d b e t w e e n disparate behaviors s u c h as

rape a n d e m b e z z l e m e n t in this theory is that they are choices m a d e

by the criminal actor in the k n o w l e d g e that he is defying a criminal

proscription w h i c h is m u t u a l l y intelligible to actors in the society as

criminal. A t the e n d of C h a p t e r 2 w e will s h o w that m o s t criminal

l a w s in m o s t societies are the subject of o v e r w h e l m i n g c o n s e n s u s .

H o w e v e r , w h e n d e a l i n g w i t h the small minority of criminal laws

that are not c o n s e n s u a l l y regarded as justified, as w i t h laws against

m a r i j u a n a use in liberal d e m o c r a c i e s or laws that create political

crimes against the state in c o m m u n i s t societies, the theory of rein-

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

4 Crime, shame and reintegration

tegrative s h a m i n g will not e x p l a i n the i n c i d e n c e o f their violation. In

liberal d e m o c r a c i e s the crimes that involve doubtful c o n s e n s u s are

v i c t i m l e s s crimes. T h u s , the w a y to e l i m i n a t e this p r o b l e m is by

m e a s u r i n g crime rates b a s e d o n l y o n predatory offenses against

p e r s o n s a n d property (Braithwaite, 1979: 10-16).

I f the a w a r e n e s s that a n act is criminal f u n d a m e n t a l l y c h a n g e s the

c h o i c e s b e i n g m a d e , t h e n the key to a general e x p l a n a t i o n o f crime

lies in identifying variables that e x p l a i n the c a p a c i t y o f s o m e indi-

v i d u a l s a n d collectivities to resist, ignore, or s u c c u m b to the institu-

tionalized d i s a p p r o v a l that g o e s w i t h crime. I n d e e d , the theory in

this book c o n s t r u e s as the critical variable o n e type o f informal social

s u p p o r t for the institutionalized d i s a p p r o v a l o f the criminal law.

T h i s variable is s h a m i n g .

C o n t r a r y to the c l a i m s o f s o m e labeling theorists, potent s h a m i n g

directed at offenders is the essential necessary c o n d i t i o n for low

c r i m e rates. Y e t s h a m i n g c a n be c o u n t e r p r o d u c t i v e if it is disintegra-

tive rather t h a n reintegrative. S h a m i n g is c o u n t e r p r o d u c t i v e w h e n it

p u s h e s offenders into the clutches o f criminal subcultures; s h a m i n g

controls crime w h e n it is at the s a m e time powerful a n d b o u n d e d by

c e r e m o n i e s to reintegrate the offender back into the c o m m u n i t y of

r e s p o n s i b l e citizens. T h e labeling perspective has failed to disting-

uish the c r i m e - p r o d u c i n g c o n s e q u e n c e s of s t i g m a that is o p e n -

e n d e d , o u t c a s t i n g , a n d p e r s o n - rather t h a n offense-centered from the

c r i m e - r e d u c i n g c o n s e q u e n c e s o f s h a m i n g that is reintegrative. T h i s

is w h y there is s u c h limited empirical support for the key predictions

o f l a b e l i n g theory.

A s t u t e scholars o f criminological theory will already be c o n c e r n e d

a b o u t m y formulation. Braithwaite, they will say, is setting out to

build u p o n t w o m u t u a l l y inconsistent theoretical traditions. O n e is

control theory, w h i c h , like m y theory, begins from the proposition

that there is f u n d a m e n t a l c o n s e n s u s a b o u t , a n d rejection of, criminal

b e h a v i o r in the society. T h e s e c o n d is subcultural theory, w h i c h is a

theory o f d i s s e n s u s , of s o m e g r o u p s h a v i n g different v a l u e s from

o t h e r s in relation to criminal behavior. I n C h a p t e r 2, I will argue

that this o p p o s i t i o n h a s b e e n greatly o v e r d r a w n in theoretical d e -

b a t e w i t h i n c r i m i n o l o g y . I n fact, only very e x t r e m e forms o f s u b -

cultural theory are irreconcilable w i t h control a n d other c o n s e n s u s -

b a s e d theories.

T h i s is not a book w h i c h p u t s a torch to existing general theories

to build a n e w theory u p o n their a s h e s . R a t h e r it sees e n o r m o u s

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Whither criminological theory? 5

s c o p e for integrating s o m e of the major theoretical traditions w h i c h

h a v e c o m e to us largely from A m e r i c a n sociological c r i m i n o l o g y -

control theory, subcultural theory, differential association, strain

theories, a n d i n d e e d labeling theory. T h e key to s y n t h e s i z i n g these

potentially i n c o m p a t i b l e formulations is to inject a vital e l e m e n t

m i s s i n g in criminological theory - reintegrative s h a m i n g .

T h e s e theories c a m e u n d e r concerted attack through the 1970s

from the ' n e w criminologists'. T o d a y they are under attack from

p r o p h e t s o f a n e w classicism in criminology. M y c o n t e n t i o n is that

the m i d d l e range theories of the fifties a n d sixties h a v e survived the

assault of the critical criminologists of the seventies a n d the n e o -

classical criminologists of the eighties rather m o r e a d m i r a b l y than

w e are inclined to c o n c e d e w h e n w e teach u n d e r g r a d u a t e criminolo-

gy. Y e t this is not to d e n y h o w profoundly i m p o r t a n t the m i s s i n g

e l e m e n t s in m i d d l e range criminological theory h a v e b e e n . T h e p a t h

to integrating these theories into m u t u a l l y reinforcing partial ex-

p l a n a t i o n s is not as difficult as has typically b e e n s u g g e s t e d . If w e

fail to take this p a t h w e are left w i t h a criminology w h i c h is the worst

of all possible w o r l d s . T h e next section is d e v o t e d to s h o w i n g h o w

c r i m i n o l o g y increasingly runs a risk of m a k i n g the worst possible

c o n t r i b u t i o n to m o d e r n societies.

O n c e w e p u t this p e s s i m i s t i c analysis of the c o n t e m p o r a r y s c e n e

b e h i n d u s , h o w e v e r , a n d g o back to the positive theoretical legacy of

the fifties a n d sixties left by great A m e r i c a n criminologists s u c h as

S u t h e r l a n d , C r e s s e y , Hirschi, C l o w a r d a n d O h l i n , Albert C o h e n ,

a n d W o l f g a n g , there is s o m e t h i n g quite substantial a n d empirically

s u s t a i n a b l e to build u p o n .

C r i m i n o l o g y as a C a u s e of C r i m e ?

A t least half of the m o s t influential criminologists in the world are

A m e r i c a n s . It is not the p u r p o s e of this chapter to s u g g e s t that the

U n i t e d States has crime p r o b l e m s so m u c h worse than other i n d u s -

trialized societies b e c a u s e it has m o r e criminologists. T h e U n i t e d

States u n d o u b t e d l y has s p e n t so lavishly o n criminology b e c a u s e it

believes this is a necessary part of a national response to reduce

crime. Y e t I a m inclined to w o n d e r w h e t h e r the professionalization

o f the s t u d y of crime is part of a wider societal m o v e m e n t w h i c h has

t e n d e d further to debilitate the social response to crime, rather than

s t r e n g t h e n it.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

6 Crime, shame and reintegration

C r i m i n o l o g y h a s b e c o m e a n export service industry for the U n i t e d

States in recent d e c a d e s . T h i r d W o r l d criminal j u s t i c e professionals

are a c c u s t o m e d to discreet j o k e s a b o u t A m e r i c a n criminologists

b e i n g f u n d e d as U N c o n s u l t a n t s , or by s o m e other form o f foreign

a i d , to c o m m u n i c a t e w o r d s o f w i s d o m to countries that m a n a g e their

c r i m e p r o b l e m s m u c h m o r e effectively t h a n the U n i t e d States. T h e r e

are r e a s o n s for fearing that s u c h foreign aid exports not o n l y A m e r -

i c a n c r i m i n o l o g y , b u t m a y risk also the export of A m e r i c a n crime

rates.

Professional c r i m i n o l o g y , in all its major variants, can be u n h e l p -

ful in m a i n t a i n i n g a social c l i m a t e appropriate to crime control

b e c a u s e in different w a y s its thrust is to professionalize, s y s t e m a t i z e ,

scientize, a n d de-Communitize j u s t i c e . T o the extent that the c o m -

m u n i t y g e n u i n e l y c o m e s to believe that the 'experts' can scientifical-

ly prescribe solutions to the crime p r o b l e m , there is a risk that

citizens c e a s e to look to the preventive obligations w h i c h are fun-

d a m e n t a l l y in their o w n h a n d s . T h u s , if I observe an offense, or if I

c o m e to k n o w that m y n e x t - d o o r n e i g h b o r is breaking the law, I

s h o u l d m i n d m y o w n b u s i n e s s , b e c a u s e there are professionals called

police officers to deal w i t h this p r o b l e m . If a child toward w h o m I

b e a r s o m e responsible relationship by virtue of kinship or c o m m u n -

ity h a s p r o b l e m s o f d e l i n q u e n c y , I m i g h t a s s u m e that it is best to

l e a v e it to the school counselor, w h o , unlike m e , is a n expert.

B u t e x a c t l y h o w is c r i m i n o l o g y i m p l i c a t e d in this process o f

e m a s c u l a t i n g c o m m u n i t y crime control? T o a n s w e r this q u e s t i o n ,

w e m u s t look separately at the three major traditions o f policy

a d v i c e that h a v e flowed from criminology: the utilitarian, the n e o -

classical, a n d the liberal-permissive.

T h e utilitarian tradition is u n d e r p i n n e d by criminological s c h o -

larship c o n c e r n e d w i t h the d e s i g n of deterrent, rehabilitative a n d

i n c a p a c i t a t i v e strategies to reduce crime. C r i m i n o l o g i s t s following

this tradition of policy a d v i c e tell the c o m m u n i t y that scientific

control of crime is p o s s i b l e if criminal j u s t i c e professionals i m p o s e

the right p e n a l t i e s o n the right p e o p l e for the right crimes, or if

t h e r a p e u t i c professionals a p p l y appropriate rehabilitative techni-

q u e s , or if criminal j u s t i c e professionals select the right p e o p l e to be

i n c a p a c i t a t e d by other criminal j u s t i c e professionals. U n d e r all uti-

litarian variants, the thrust of criminological advice is toward pro-

fessionals taking over in different w a y s to m a k e j u d g m e n t s for the

c o m m u n i t y , informed by science, to prevent crime.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Whither criminological theory? 7

T h e neo-classical tradition of policy advice d e n i e s the capacity of

c r i m i n o l o g y to deliver s o u n d professional g u i d a n c e o n h o w to reduce

crime. H o w e v e r , it p r o m i s e s another kind of professionalization of

j u s t i c e . It proffers a s y s t e m a t i z i n g of p u n i s h m e n t s by jurisprudential

professionals so that they reflect the desert of defendants. T h e n e o -

classical m o d e l takes special affront at c o m m u n i t i e s informally re-

s o l v i n g crime p r o b l e m s outside the j u s t i c e s y s t e m . Police officers

s h o u l d not be a l l o w e d the discretion to 'kick kids in the pants'.

Serious criminal offenses s h o u l d not be dealt w i t h by school princip-

als sitting d o w n w i t h parents to try to sort out the p r o b l e m s of a

youthful offender: if a serious crime has b e e n c o m m i t t e d , that is a

m a t t e r for the courts, a n d the courts s h o u l d a d m i n i s t e r the deserved

p u n i s h m e n t . For the neo-classicists, informal c o m m u n i t y involve-

m e n t in crime control risks both excessive o p p r e s s i o n and excessive

l e n i e n c y by d o - g o o d e r s . C o m m u n i t y j u s t i c e is unpredictable, i n c o n -

sistent, a n d unjust. T h e ideal is a professionalized j u s t i c e that is

m e a s u r e d to deliver s y s t e m a t i c a l l y neither m o r e nor less than offen-

ders deserve.

T h e liberal-permissive tradition of policy advice is g r o u n d e d in

the l a b e l i n g perspective. Becker (1963:9) told us that

d e v i a n c e is n o t a q u a l i t y o f the a c t a p e r s o n c o m m i t s but rather a c o n s e q u -

e n c e o f the a p p l i c a t i o n b y o t h e r s o f rules a n d s a n c t i o n s to a n offender. T h e

d e v i a n t is o n e to w h o m that l a b e l h a s s u c c e s s f u l l y b e e n a p p l i e d ; d e v i a n t

b e h a v i o r is b e h a v i o r that p e o p l e s o label.

O r , as a n o t h e r labelist, K i t s u s e (1962: 2 5 3 ) , put it:

F o r m s o f b e h a v i o r p e r se d o n o t differentiate d e v i a n t s from n o n - d e v i a n t s ; it

is t h e r e s p o n s e s o f the c o n v e n t i o n a l a n d c o n f o r m i n g m e m b e r s o f s o c i e t y w h o

identify a n d interpret b e h a v i o r as d e v i a n t w h i c h s o c i o l o g i c a l l y transform

persons into deviants.

T h e l a b e l i n g perspective w a s i m p o r t a n t to the d e v e l o p m e n t of

c r i m i n o l o g y as a n empirical science b e c a u s e it fostered a n apprecia-

tive s t a n c e t o w a r d offenders. W h i l e positivist criminology u p to that

point h a d s e e n offenders very m u c h as d e t e r m i n e d creatures, the

l a b e l i n g p e r s p e c t i v e o p e n e d m a n y eyes to the w a y offenders were

c h o o s i n g b e i n g s , i n v o l v e d in s h a p i n g their o w n destiny. T h e y had an

interpretation of w h a t the world w a s d o i n g to t h e m , and w h a t they

w e r e d o i n g to it, w h i c h w a s frequently at o d d s w i t h the official

version that positivist c r i m i n o l o g y h a d taken for granted. T h e policy

prescription that g r e w from this appreciative stance toward the

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

8 Crime, shame and reintegration

d e v i a n t w a s a call for tolerance a n d u n d e r s t a n d i n g , a plea to the

c o m m u n i t y to see the d e v i a n t as m o r e sinned against than sinning,

to l e a v e the d e l i n q u e n t alone, to see d e l i n q u e n c y as 'just part o f

g r o w i n g u p ' . W h i l e it w a s a g o o d thing for the c o m m u n i t y to c o m e to

u n d e r s t a n d the m a n y w a y s in w h i c h the d e v i a n t w a s sinned against,

the l a b e l i n g perspective w a s also telling the c o m m u n i t y to m i n d its

o w n b u s i n e s s . Certainly, it w a s at the s a m e time telling the criminal

j u s t i c e professionals to keep their noses out o f the affairs o f d e v i a n t s .

T h u s , w h i l e the utilitarians a n d neo-classicists were giving the c o m -

m u n i t y the m e s s a g e that c o m m u n i t y i n v o l v e m e n t in crime control

c o u l d be d r o p p e d d o w n their a g e n d a b e c a u s e the professionals

w o u l d take care o f it, the liberal-permissive tradition of c r i m i n o l o g y

w a s telling e v e r y b o d y , professionals a n d the c o m m u n i t y , to try

'radical n o n - i n t e r v e n t i o n ' (Schur, 1973).

If the theory in this book is correct, the t e n d e n c y o f e a c h of these

major traditions o f criminological policy a d v i c e to imply a neutra-

lization o f c o m m u n i t y activism in crime control positively encour-

a g e s crime. C r i m e is best controlled w h e n m e m b e r s of the c o m m u n -

ity are the primary controllers through active participation in s h a m -

ing offenders, a n d , h a v i n g s h a m e d t h e m , through concerted parti-

c i p a t i o n in w a y s o f reintegrating the offender back into the c o m m u n -

ity o f l a w a b i d i n g citizens. L o w crime societies are societies w h e r e

p e o p l e d o not m i n d their o w n b u s i n e s s , w h e r e tolerance o f d e v i a n c e

h a s definite limits, w h e r e c o m m u n i t i e s prefer to h a n d l e their o w n

crime p r o b l e m s rather than h a n d t h e m over to professionals. I n this,

I a m not s u g g e s t i n g the r e p l a c e m e n t o f 'the rule o f law' w i t h 'the

rule o f m a n ' . H o w e v e r , I a m s a y i n g that the rule o f l a w will a m o u n t

to a m e a n i n g l e s s set o f formal s a n c t i o n i n g p r o c e e d i n g s w h i c h will be

p e r c e i v e d as arbitrary unless there is c o m m u n i t y i n v o l v e m e n t in

m o r a l i z i n g a b o u t a n d h e l p i n g w i t h the crime p r o b l e m .

T h e r e is a fourth p r o m i n e n t tradition o f policy a d v i c e w h i c h ,

unlike the other three, d o e s not r e c o m m e n d c h a n g e s to the criminal

j u s t i c e s y s t e m . T h i s fourth tradition is p o p u l a t e d by M a r x i s t s w h o

see the o v e r t h r o w o f c a p i t a l i s m as a route to a crime-free society, or

at least to a society w i t h m u c h less crime, a n d o p p o r t u n i t y theorists

s u c h as those d i s c u s s e d in the next chapter, w h o see other fun-

d a m e n t a l structural c h a n g e s , m a i n l y in class inequalities, as policies

for c r i m e reduction. Sadly, h o w e v e r , the policy a d v i c e of c r i m i n o l o g -

ists is o n l y ever taken seriously w h e n it is directed at the criminal

j u s t i c e s y s t e m , so this fourth major tradition o f criminological policy

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Whither criminological theory? 9

a d v i c e is o f n o c o n s e q u e n c e in influencing events. T h e world is yet to

see a socialist revolution inspired by the desire to eliminate crime;

a n d in m y o w n c a p a c i t y as a m e m b e r of Australia's Economic

P l a n n i n g A d v i s o r y C o u n c i l , I w a i t e d four years w i t h o u t w i t n e s s i n g a

s u g g e s t i o n that a consideration against o n e policy choice rather than

a n o t h e r w a s the i m p a c t o n crime.

N o n e o f this is to d e n y that there h a v e not b e e n s o m e t r e m e n d o u s -

ly v a l u a b l e pockets of policy a d v i c e supplied by criminology. In

C h a p t e r s 9 a n d 10 a n u m b e r of t h e m will be d i s c u s s e d . Perhaps s u c h

c o n t r i b u t i o n s h a v e m e a n t that criminology has m a d e more positive

t h a n n e g a t i v e c o n t r i b u t i o n s to crime control. W e will never k n o w

the a n s w e r to a q u e s t i o n like this. T h e c o n t e n t i o n here has b e e n

s i m p l y that the three major traditions of policy advice run a real risk

o f c o u n t e r p r o d u c t i v i t y if the theory in this book is correct.

Human Agency and Criminological Theory

C r i m i n o l o g i c a l theory has t e n d e d to a d o p t a rather passive c o n c e p -

tion o f the criminal. C r i m i n a l b e h a v i o r is d e t e r m i n e d by biological,

p s y c h o l o g i c a l a n d social structural variables over w h i c h the criminal

h a s little control. T h e theory of reintegrative s h a m i n g , in contrast,

a d o p t s a n active c o n c e p t i o n of the criminal. T h e criminal is seen as

m a k i n g c h o i c e s - to c o m m i t crime, to j o i n a subculture, to a d o p t a

d e v i a n t self-concept, to reintegrate herself, to respond to others'

gestures o f reintegration - against a b a c k g r o u n d of societal pressures

m e d i a t e d by s h a m i n g .

T h e latter pressures m i g h t m e a n that the choices are s o m e w h a t

c o n s t r a i n e d c h o i c e s , b u t they are choices. T h i s is especially so

b e c a u s e the theory of reintegrative s h a m i n g explains c o m p l i a n c e

w i t h the l a w by the m o r a l i z i n g qualities of social control rather than

by its repressive qualities. S h a m i n g is c o n c e i v e d as a tool to allure

a n d i n v e i g l e the citizen to attend to the moral claims of the criminal

law, to c o a x a n d caress c o m p l i a n c e , to reason and remonstrate w i t h

h i m over the harmfulness of his c o n d u c t . T h e citizen is ultimately

free to reject these a t t e m p t s to p e r s u a d e through social disapproval.

A n irony o f the theory is the c o n t e n t i o n that moralizing social

control is m o r e likely to secure c o m p l i a n c e w i t h the law than repres-

sive social control. B e c a u s e criminal b e h a v i o r is m o s t l y harmful by

a n y m o r a l yardstick, a n d agreed to be so by m o s t citizens, moraliz-

ing a p p e a l s w h i c h treat the citizen as s o m e o n e w i t h the responsibil-

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

10 Crime, shame and reintegration

ity to m a k e the right c h o i c e are generally, t h o u g h not invariably,

r e s p o n d e d to m o r e positively than repressive controls w h i c h d e n y

h u m a n d i g n i t y by treating persons as a m o r a l calculators. A culture

i m p r e g n a t e d w i t h high moral e x p e c t a t i o n s o f its citizens, p u b l i c l y

e x p r e s s e d , will deliver superior crime control c o m p a r e d w i t h a cul-

ture w h i c h sees control as a c h i e v a b l e by inflicting p a i n o n its b a d

apples.

I n a d d i t i o n to the e p i s t e m o l o g i c a l rationale for c o n c e i v i n g p e o p l e

as c h o o s i n g in light o f societal pressures rather than b e i n g deter-

m i n e d by t h e m , there is thus also s u g g e s t e d a n empirical rationale:

m o r a l i z i n g w h i c h then leaves a g e n c y in the h a n d s of the citizen is

m o r e likely to work in the l o n g run than a policy of a t t e m p t i n g to

r e m o v e a g e n c y from the citizen by repressive control. T h e e p i s t e m o -

logical c l a i m a n d the empirical c l a i m are linked to a n o r m a t i v e

claim: a shift o f the b a l a n c e o f social control a w a y from repression

a n d t o w a r d social control by m o r a l i z i n g is a g o o d thing. T h e tradi-

tion o f linking the empirical c l a i m that repressive control d o e s not

work w i t h the n o r m a t i v e c l a i m that it is w r o n g dates at least from

Dürkheim:

Ideas and feelings need not be expressed through... untoward manifestations

of force, in order to be communicated. As a matter of fact such punishments

constitute today quite a serious moral handicap. They affront a feeling that

is at the bottom of all our morality, the religious respect in which the human

person is held. By virtue of this respect, all violence exercised on a person

seems to us, in principle, like sacrilege. In beating, in brutality of all kinds,

there is something we find repugnant, something that revolts our conscience

— in a word, something immoral. Now, defending morality by means repudi-

ated by it, is a remarkable way of protecting morality. It weakens on the one

hand the sentiments that one wishes to strengthen on the other.

(Dürkheim, 1961: 182-3)

H e n c e , s h a m i n g is c o n c e i v e d in this theory as a m e a n s of m a k i n g

citizens actively responsible, of informing t h e m of h o w justifiably

resentful their fellow citizens are toward criminal b e h a v i o r w h i c h

h a r m s t h e m . I n practice, s h a m i n g surely limits a u t o n o m y , m o r e

surely t h a n repression, b u t it d o e s so by c o m m u n i c a t i n g moral

c l a i m s o v e r w h i c h other citizens c a n reasonably be e x p e c t e d to

express d i s g u s t s h o u l d w e c h o o s e to ignore t h e m . In other w o r d s ,

s h a m i n g is a route to freely c h o s e n c o m p l i a n c e , w h i l e repressive

social control is a route to coerced c o m p l i a n c e . Repressive social

control, as by i m p r i s o n m e n t , restricts our a u t o n o m y by forced

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Whither criminological theory? 11

l i m i t a t i o n o f our choices; m o r a l i z i n g social control restricts our

a u t o n o m y by inviting us to see that w e c a n n o t be w h o l e moral

p e r s o n s t h r o u g h c o n s i d e r i n g only our o w n interests in the choices w e

m a k e . W e are s h a m e d if w e exercise our o w n a u t o n o m y in a w a y

that t r a m p l e s o n the a u t o n o m y of others.

A m o r a l e d u c a t i v e n o r m a t i v e theory of social control aspires to

p u t the a c c u s e d in a position w h e r e she m u s t either argue for her

i n n o c e n c e , a d m i t guilt a n d express remorse, or contest the legitima-

cy o f the n o r m s she is a c c u s e d of infringing. It seeks to foreclose the

alternative of t e r m i n a t i n g moral reasoning over alleged w r o n g d o i n g

by 'exclusion' of the a c c u s e d . S u c h a theory therefore a c c o m m o d a t e s

civil d i s o b e d i e n c e better t h a n traditional theories o f p u n i s h m e n t . A

moral e d u c a t i o n theory forges a vital role for q u e s t i o n i n g by the

p e r s o n w h o c h a l l e n g e s the j u s t i c e of the n o r m a t i v e order: she forces

the state 'to c o m m i t itself, in full v i e w of the rest of society, to the

idea that her actions s h o w she n e e d s moral e d u c a t i o n ' ( H a m p t o n ,

1984: 2 2 1 ) . A deterrence theory, in contrast, raises n o p r o b l e m s w i t h

the s i l e n c i n g o f critics, the suffocation of moralizing o n both sides, by

locking the offender a w a y from c o m m u n i t y contact.

For s o m e readers the theory of reintegrative s h a m i n g will u n -

d o u b t e d l y raise the spectre of a society of informers a n d b u s y b o d i e s ,

of t h o u g h t control, a society w h e r e i n diversity c a n n o t be tolerated.

S h a m i n g c a n foster s u c h a society. A s Andrei Siniavsky said in his

trial before the People's T r i b u n a l in M o s c o w , 1966:

Think of it please, I am different from others, yes different, but I am not an

enemy. I am a soviet person and my art is not subversive - it is only

different. In this tense atmosphere anything which is different would seem

subversive - but why do you have to look for enemies, to create monsters

where there are none? (Quoted in Shoham, 1970: 98)

S i n i a v s k y m a k e s t w o pleas here. H e asks not to be treated as a

'monster'. ( I n the l a n g u a g e of m y theory, he asks not to be s t i g m a -

tized.) S e c o n d , he is c l a i m i n g that his art d o e s n o h a r m a n d there-

fore s h o u l d be tolerated. T h e s e are reasonable pleas. Behavior

s h o u l d never be p u n i s h e d or publicly s h a m e d as criminal if it risks

n o h a r m to other citizens; a n d e v e n w h e n it d o e s h a r m , the offender

s h o u l d be s h a m e d or p u n i s h e d w i t h dignity rather than stigmatized

as a m o n s t e r or outcast.

S h a m i n g w h i c h c o m p l i e s w i t h these t w o requirements will not be

oppressive. Shaming which eschews stigmatization, which shames

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

12 Crime, shame and reintegration

w i t h i n a c o n t i n u u m o f h u m a n respect, m a x i m i z e s prospects that

b e h a v i o r w h i c h is n o t harmful to others will b e tolerated. I n a liberal

society, s h a m i n g is n e e d e d to s a n c t i o n t h o s e w h o d o h a r m b y res-

tricting the freedom o f others to e n g a g e in n o n - c r i m i n a l d e v i a n c e .

A society w h i c h neglects the n e e d to s h a m e harmful criminal

b e h a v i o r will be a society w h i c h e n c o u r a g e s its citizens to a m o r a l

e n c r o a c h m e n t s u p o n the freedom o f others. In C h a p t e r 9, it will be

a r g u e d that societies w h i c h fail to exercise informal social control

w i t h i n local c o m m u n i t i e s , families, schools a n d other p r o x i m a t e

g r o u p s find t h e m s e l v e s w i t h n o political c h o i c e but to resort to

repressive control by the state. C o m m u n i t a r i a n societies, it will be

a r g u e d , are m o r e free to c h o o s e their m i x b e t w e e n formal state

control a n d informal c o m m u n i t y control. Effective c o m m u n i t a r i a n

s h a m i n g therefore e x p a n d s the s c o p e for p u r s u i n g less repressive

criminal j u s t i c e policies. A s F e i n b e r g put it: T o d a y w e prefer not to

b e c o m e i n v o l v e d in the control o f crime, w i t h the result that those

w h o are c h a r g e d w i t h the control o f crime b e c o m e m o r e a n d m o r e

i n v o l v e d w i t h us* (Feinberg, 1970:240).

S h a m i n g is a d a n g e r o u s g a m e . D o n e oppressively, it c a n be used

for t h o u g h t control a n d stultification of h u m a n diversity. N o t d o n e

m u c h at all, it u n l e a s h e s a w a r o f all against all, the m a x i m a l l y

repressive state, a n d tolerance o f a situation w h e r e s o m e citizens

t r a m p l e o n the rights o f others. W h i c h e v e r w a y w e play it, it is a

g a m e that matters. H a p p i l y , the w a y the s h a m i n g g a m e unfolds is

not i n e x o r a b l y d e t e r m i n e d . T h e r e is s c o p e for political choice; this

s c o p e for h u m a n a g e n c y m a k e s it worth our while d e v e l o p i n g a n

u n d e r s t a n d i n g o f the p o w e r o f s h a m i n g .

A Preliminary Sketch of the T h e o r y

T h e first s t e p to p r o d u c t i v e theorizing a b o u t crime is to think a b o u t

the c o n t e n t i o n that l a b e l i n g offenders m a k e s things worse. The

c o n t e n t i o n is b o t h right a n d w r o n g . T h e theory o f reintegrative

s h a m i n g is a n a t t e m p t to specify w h e n it is right and w h e n w r o n g .

T h e distinction is b e t w e e n s h a m i n g that leads to s t i g m a t i z a t i o n - to

o u t c a s t i n g , to confirmation o f a d e v i a n t m a s t e r status - versus

s h a m i n g that is reintegrative, that s h a m e s w h i l e m a i n t a i n i n g b o n d s

o f respect or love, that sharply terminates disapproval w i t h forgive-

n e s s , instead o f amplifying d e v i a n c e by progressively casting the

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Whither criminological theory? 13

d e v i a n t out. R e i n t e g r a t i v e s h a m i n g controls crime; stigmatization

p u s h e s offenders t o w a r d criminal subcultures.

T h e s e c o n d s t e p to m o r e p r o d u c t i v e theorizing a b o u t crime is to

realize w h a t scholars like S u t h e r l a n d , Cressey and Glaser grasped

l o n g a g o - that criminality is a function of the ratio of associations

favorable to crime to those unfavorable to crime. If this is a banal

point, it is o n e that criminological theorists systematically forget. A s

D a n i e l G l a s e r c o m m e n t e d o n a n earlier draft of this book:

What we need to develop and operationalize in various social contexts is a

theory of tipping points, of the persons and circumstances in which particu-

lar types of labeling and punishment shift the predominant stake of the

subjects from conformity to nonconformity with the legal norms, and vice

versa. Much of the difference between delinquency theorists reflects the fact

that the samples they studied were on different sides of this tipping point.

Hirshi focussed on the 75 percent of a cross-section of secondary school

students who completed his questionnaires, and were predominantly not

very delinquent, while Shaw and McKay as well as Murray and Cox

studied repeatedly arrested youths in delinquent and criminal gangs from

high crime-rate slums. Like the blind Hindus in the legend, each general-

ized from the different parts of the elephant that they encountered.

T h e theory of reintegrative s h a m i n g c o n t e n d s that w e can sensibly

talk a b o u t criminal subcultures. W e require a theory w h i c h c o m e s to

grips w i t h the m u l t i p l e moralities w h i c h exist in contemporary

societies. A severe limitation of theories that d e n y this, like Hirschi's

control theory, is that they give no a c c o u n t of w h y s o m e uncontrol-

led i n d i v i d u a l s b e c o m e heroin users, s o m e b e c o m e hit m e n , a n d

others price fixing conspirators. A t the s a m e time, w e m u s t recog-

nize that the criminal law is a powerfully d o m i n a n t majoritarian

morality c o m p a r e d w i t h the minority subculture of the heroin user

or the industry association's price fixing circle. T h e r e is a powerful

c o n s e n s u s in m o d e r n industrial societies over the Tightness of cri-

m i n a l l a w s w h i c h protect our persons and property, if not over

v i c t i m l e s s crimes. E v e n m o s t criminal subcultures d o not transmit

an outright rejection of the criminal law, rather they transmit m e a n s

of rationalizing temporary s u s p e n s i o n of one's c o m m i t m e n t to the

law, s y m b o l i c resources for insulating the offender from s h a m e .

T h e theory is o n e of predatory crime - w h e t h e r perpetrated by

j u v e n i l e d e l i n q u e n t s , street offenders or business executives - of

violations of criminal laws w h i c h prohibit o n e person from preying

o n others. Societies that s h a m e effectively will be more successful in

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

14 Crime, shame and reintegration

controlling predatory crime b e c a u s e there will be m o r e s h a m i n g

directed at n o n c o m p l i a n c e w i t h the l a w than s h a m i n g (within s u b -

cultures) for c o m p l y i n g w i t h the l a w . It is i m p o r t a n t to u n d e r s t a n d

that for d o m a i n s w h e r e the criminal law d o e s not represent a clearly

majoritarian morality, the theory o f reintegrative s h a m i n g will fail to

e x p l a i n variation in behavior. It provides a thoroughly i n a d e q u a t e

a c c o u n t o f n o n p r e d a t o r y criminal b e h a v i o r like h o m o s e x u a l i t y be-

c a u s e , e v e n in a society w i t h great capacities to s h a m e effectively, if

h a l f the p o p u l a t i o n d o e s not believe the b e h a v i o r s h o u l d be criminal-

ized, there m a y be as m u c h s h a m i n g directed at g a y s w h o refuse to

c o m e o u t o f the closet, a n d at those w h o oppress h o m o s e x u a l s , as

there is s h a m i n g directed at the offending itself. T h e theory of

reintegrative s h a m i n g is not a satisfactory general theory of d e v i a n c e

b e c a u s e its e x p l a n a t o r y p o w e r declines as d i s s e n s u s increases over

w h e t h e r the c o n d u c t s h o u l d be v i e w e d as d e v i a n t . It is best reserved

for that d o m a i n w h e r e there is strong c o n s e n s u s , that o f predatory

c r i m e s (crimes i n v o l v i n g v i c t i m i z a t i o n of o n e party by a n o t h e r ) .

W h i l e it is true w i t h respect to this d o m a i n that criminal s u b c u l -

tures are a l w a y s minority p h e n o m e n a , s o m e types of societies will

h a v e m o r e virulent criminal subcultures than others. For e x a m p l e ,

societies w h i c h segregate o p p r e s s e d racial minorities into s t i g m a -

tized n e i g h b o r h o o d s create the c o n d i t i o n s for criminal subculture

formation.

T h e theory of reintegrative s h a m i n g posits that the c o n s e q u e n c e

o f s t i g m a t i z a t i o n is attraction to criminal subcultures. S u b c u l t u r e s

s u p p l y the o u t c a s t offender w i t h the o p p o r t u n i t y to reject her rejec-

tors, thereby m a i n t a i n i n g a form of self-respect. In contrast, the

c o n s e q u e n c e o f reintegrative s h a m i n g is that criminal subcultures

a p p e a r less attractive to the offender. S h a m i n g is the m o s t p o t e n t

w e a p o n o f social control unless it s h a d e s into s t i g m a t i z a t i o n . F o r m a l

criminal p u n i s h m e n t is a n ineffective w e a p o n of social control partly

b e c a u s e it is a d e g r a d a t i o n c e r e m o n y w i t h m a x i m u m prospects for

stigmatization.

T h e n u b o f the theory of reintegrative s h a m i n g is therefore a b o u t

the effectiveness of reintegrative s h a m i n g and the counterproductiv-

ity of s t i g m a t i z a t i o n in controlling crime. In addition, the theory

posits a n u m b e r o f c o n d i t i o n s that m a k e for effective shaming.

I n d i v i d u a l s are m o r e susceptible to s h a m i n g w h e n they are en-

meshed in multiple relationships of interdependency; societies

s h a m e m o r e effectively w h e n they are c o m m u n i t a r i a n . V a r i a b l e s like

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

Whither criminological theory? 15

urbanization and residential mobility predict communitarianism,

while variables like age and gender predict individual inter-

d e p e n d e n c y . A schematic summary o f these aspects o f the theory is

presented in Figure 1 (page 94).

S o m e o f the ways that the theory o f reintegrative shaming builds

o n earlier theories should now be clear. I n t e r d e p e n d e n c y is the stuff

o f control theory; stigmatization c o m e s from labeling theory; subcul-

ture formation is accounted for in opportunity theory terms; sub-

cultural influences are naturally in the realm o f subcultural theory;

and the whole theory can be understood in integrative cognitive

social learning theory terms such as are provided by differential

association.

Given that we plan to integrate elements o f all these traditions

into o n e theoretical framework, we cannot escape the labor o f sum-

marizing the things they have to say that are relevant. T h i s we d o in

the next chapter, along with a justification o f the premise that

substantial consensus over the evil o f predatory crime exists in

m o d e r n societies. Readers w h o are not particularly interested in an

account o f these theories, o f their strengths and o f the limitations

requiring redress by a more encompassing theory, n e e d only read

just the first section o n labeling and the conclusion to the next

chapter. Chapter 3 then runs through the facts a theory o f crime

must fit to be credible - the well established correlates o f crime - and

argues that the dominant theoretical traditions, read in isolation

from each other, d o not supply a compelling account of these facts.

Less than diligent readers might skim this chapter also. In Chapter 4

we get d o w n to the theory itself.

https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511804618.002 Published online by Cambridge University Press

You might also like

- Jean Baudrillard - The Mirror of CorruptionDocument6 pagesJean Baudrillard - The Mirror of Corruptionakrobata1No ratings yet

- Principles To Govern Possible Public Statement On Legislation Affecting Rights of HomosexualsDocument21 pagesPrinciples To Govern Possible Public Statement On Legislation Affecting Rights of HomosexualsPizzaCow100% (2)

- Liberation Therapeutics: Consciousness-Raising As A ProblemDocument9 pagesLiberation Therapeutics: Consciousness-Raising As A ProblemFonsecapsiNo ratings yet

- CLJ1Document1 pageCLJ1Pamela Louise MercaderNo ratings yet

- PC3 AlvaroDocument12 pagesPC3 AlvaroÁlvaro ChangNo ratings yet

- What Is Global Governance? (Lawrence Finkelstein)Document6 pagesWhat Is Global Governance? (Lawrence Finkelstein)Mayrlon CarlosNo ratings yet

- Disponibilidad para Rendir Cuentas: Jonathan APRAEZ, Alexis ERRÁEZDocument8 pagesDisponibilidad para Rendir Cuentas: Jonathan APRAEZ, Alexis ERRÁEZYomi JumboNo ratings yet

- Jean Baudrillard - Disembodied VIolence. HateDocument5 pagesJean Baudrillard - Disembodied VIolence. Hateakrobata1100% (1)

- Drug Wars Viewers GuideDocument6 pagesDrug Wars Viewers Guidetexas forumNo ratings yet

- PDF Two Nation TheoryDocument2 pagesPDF Two Nation TheoryZohaib AslamNo ratings yet

- State Immunity and The Controversy of Private Suits Against Sovering StatesDocument691 pagesState Immunity and The Controversy of Private Suits Against Sovering StateskuimbaeNo ratings yet

- HRA CHR IV A2010 005 EO No.003 Discriminatory or Rights Based CHR Advisory On The Local Ordinance by The City of ManilaDocument5 pagesHRA CHR IV A2010 005 EO No.003 Discriminatory or Rights Based CHR Advisory On The Local Ordinance by The City of ManilaKal-El Von Li YapNo ratings yet

- My Fraud DetectionDocument20 pagesMy Fraud DetectionLakshmi GurramNo ratings yet

- YOUNG, Jock. The Tasks Facing A Realist Criminology (1987)Document20 pagesYOUNG, Jock. The Tasks Facing A Realist Criminology (1987)Alexandre Fernandes SilvaNo ratings yet

- Attempted Homicide MemorandumDocument55 pagesAttempted Homicide MemorandumVictoria StephensNo ratings yet

- Jamia Milia Islamia University: Submitted By:-Mohd. Faheem Class: - Ll.M. 1 Sem. Roll No.: - 05Document36 pagesJamia Milia Islamia University: Submitted By:-Mohd. Faheem Class: - Ll.M. 1 Sem. Roll No.: - 05Mohd FaheemkhanNo ratings yet

- A Simple and Effective Cure for Criminality: A Psychological Detective StoryFrom EverandA Simple and Effective Cure for Criminality: A Psychological Detective StoryNo ratings yet

- The LEXICON - Taylor's Law School's Legal Newsletter (2013)Document40 pagesThe LEXICON - Taylor's Law School's Legal Newsletter (2013)stellchaiNo ratings yet

- The Art of ThinkingDocument7 pagesThe Art of ThinkingRifqi Khairul AnamNo ratings yet

- Seelig Frederick - Destroy The AccuserDocument195 pagesSeelig Frederick - Destroy The AccuserDoctorBuzzard RootworkerNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Psychoanalysis: To Cite This Article: Peter Lawner Ph.D. (1989) Counteridentification, TherapeuticDocument18 pagesContemporary Psychoanalysis: To Cite This Article: Peter Lawner Ph.D. (1989) Counteridentification, Therapeuticv_azygosNo ratings yet

- Du Bois, Lindsey Torture - and - The - Construction - of - An - EnemyDocument12 pagesDu Bois, Lindsey Torture - and - The - Construction - of - An - EnemyMarcela RuggeriNo ratings yet

- Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and IrelandDocument4 pagesRoyal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and IrelandGuilherme BorgesNo ratings yet

- Ethics of Co-OperationDocument13 pagesEthics of Co-OperationRobert LotzerNo ratings yet

- Jean Baudrillard - World Debt and Parallel UniverseDocument5 pagesJean Baudrillard - World Debt and Parallel Universeakrobata1100% (1)

- Tilly - 1975 - Revolutions and Collective ViolenceDocument137 pagesTilly - 1975 - Revolutions and Collective ViolenceRobNo ratings yet

- Article 3 - 1987 ConstitutionDocument111 pagesArticle 3 - 1987 ConstitutionTherese Angelie CamacheNo ratings yet

- The Economics of EthicsDocument11 pagesThe Economics of EthicshaidaNo ratings yet

- 83 PDFDocument137 pages83 PDFVannessa MoralesNo ratings yet

- Jean Baudrillard - Helots and ElitesDocument6 pagesJean Baudrillard - Helots and Elitesakrobata1No ratings yet

- CHR A2016 005 PDFDocument9 pagesCHR A2016 005 PDFJerry AknaNo ratings yet

- Case Studies in Crime Travel Demand Modeling: I.TravelpatternsofchicagorobberyoffendersDocument57 pagesCase Studies in Crime Travel Demand Modeling: I.Travelpatternsofchicagorobberyoffendersitpro8868No ratings yet

- Black and White Photo True Crime & Investigative Journalism Podcast Cover (Копия)Document12 pagesBlack and White Photo True Crime & Investigative Journalism Podcast Cover (Копия)kseniyamariyanchukNo ratings yet

- PA v. Cosby - Commonwealth's Motion To Introduce Evidence of Prior Bad Acts of The Defendant 09-06-16 OCRDocument68 pagesPA v. Cosby - Commonwealth's Motion To Introduce Evidence of Prior Bad Acts of The Defendant 09-06-16 OCRLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- Jean Baudrillard - We Are All Transexuals NowDocument6 pagesJean Baudrillard - We Are All Transexuals Nowakrobata1No ratings yet

- Anthropology Metaphysical Point From A of ViewDocument25 pagesAnthropology Metaphysical Point From A of Viewprabhujaya97893No ratings yet

- Ctivity Repor: Women & Child Welfare SocietyDocument24 pagesCtivity Repor: Women & Child Welfare SocietyMinatiBindhaniNo ratings yet

- 3 Billofrights2013-160128025035Document104 pages3 Billofrights2013-160128025035Ronald G. CabantingNo ratings yet

- Criminology: Criminology Is A Discipline Which Analyses and Gathers The Data of Crime andDocument10 pagesCriminology: Criminology Is A Discipline Which Analyses and Gathers The Data of Crime andRitanshi 29No ratings yet

- b10086031 PDFDocument172 pagesb10086031 PDFCarlosNo ratings yet

- Concepts of Freedom in Lenz and KlingerDocument149 pagesConcepts of Freedom in Lenz and Klingerhasunuma.r.fNo ratings yet

- The Quiet Revolution: Shattering the Myths About the American Criminal Justice SystemFrom EverandThe Quiet Revolution: Shattering the Myths About the American Criminal Justice SystemNo ratings yet

- Forst, On The Concept of Justification Narrative-CopiarDocument13 pagesForst, On The Concept of Justification Narrative-CopiarAntonio Bentura AguilarNo ratings yet

- Forst para Topico de GustavoDocument31 pagesForst para Topico de GustavoAntonio Bentura AguilarNo ratings yet

- Business Ethics (BE) 9Document1 pageBusiness Ethics (BE) 9Rajesh WariseNo ratings yet

- Scope and Importance of CriminologyDocument8 pagesScope and Importance of CriminologySalman MirzaNo ratings yet

- Definition of Crime and CriminalDocument8 pagesDefinition of Crime and CriminalBenGNo ratings yet

- DeLanda - A Thousand Years of Nonlinear HistoryDocument331 pagesDeLanda - A Thousand Years of Nonlinear Historyrdamico23100% (4)

- Death and The Desire For DeathlessnessDocument3 pagesDeath and The Desire For DeathlessnessFederico EstradaNo ratings yet

- The Need to Abolish the Prison System: An Ethical IndictmentFrom EverandThe Need to Abolish the Prison System: An Ethical IndictmentNo ratings yet

- Morality in Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure:Principles, Doctrines, and Court CasesDocument4 pagesMorality in Criminal Law and Criminal Procedure:Principles, Doctrines, and Court CasestareghNo ratings yet

- LBJ Inaugural AddressDocument2 pagesLBJ Inaugural AddressterencehkyungNo ratings yet

- Restorative Justice in The Context of Intimate Partner Violence Suggestions For Its Qualified Usage As Supplementary To The Criminal Justice SystemDocument4 pagesRestorative Justice in The Context of Intimate Partner Violence Suggestions For Its Qualified Usage As Supplementary To The Criminal Justice Systemapi-644307048No ratings yet

- Dogma - Obstruction-A Grammar For The CIty-AA FIles 54Document6 pagesDogma - Obstruction-A Grammar For The CIty-AA FIles 54Angel C. ZiemsNo ratings yet

- Treating Sexual Harassment With RespectDocument82 pagesTreating Sexual Harassment With RespectpufendorfNo ratings yet

- Importance of Criminology in PakistanDocument4 pagesImportance of Criminology in Pakistaniqra liaqatNo ratings yet

- Society, Schools and Progress in Israel: The Commonwealth and International Library: Education and Educational ResearchFrom EverandSociety, Schools and Progress in Israel: The Commonwealth and International Library: Education and Educational ResearchNo ratings yet

- 15.0 PP 217 226 IndexDocument10 pages15.0 PP 217 226 IndexmatfernandezNo ratings yet

- Paqué 1985 - How Far Is Vienna From ChicagoDocument23 pagesPaqué 1985 - How Far Is Vienna From ChicagomatfernandezNo ratings yet

- Goffman 2005 - Interaction RitualDocument26 pagesGoffman 2005 - Interaction RitualmatfernandezNo ratings yet

- McLaughlin 2007 - The New PolicingDocument154 pagesMcLaughlin 2007 - The New PolicingmatfernandezNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 7 With AnswersDocument6 pagesTutorial 7 With Answersmenna.abdelshafyNo ratings yet

- Di Paola Hoy 2005Document12 pagesDi Paola Hoy 2005Nurulhudda ArshadNo ratings yet

- PSTM (Midterm)Document10 pagesPSTM (Midterm)MONICA VILLANUEVANo ratings yet

- Research Methods Group EssayDocument3 pagesResearch Methods Group EssayRyheeme DoneganNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Guidance & Counselling in A Student's LifeDocument9 pagesThe Importance of Guidance & Counselling in A Student's LifeArlyn AlquizaNo ratings yet

- Ai Project CycleDocument14 pagesAi Project Cyclelavanya sakthiNo ratings yet

- EDU102MTH Midterm Notes #3: The Original Cognitive or Thinking DomainDocument6 pagesEDU102MTH Midterm Notes #3: The Original Cognitive or Thinking DomainsydneyNo ratings yet

- Readytoprint Bibliography Route 2Document5 pagesReadytoprint Bibliography Route 2Rascel SumalinogNo ratings yet

- Test Specification Table: Bm050-3-3-Imnpd Individual Assignment 1 of 4Document4 pagesTest Specification Table: Bm050-3-3-Imnpd Individual Assignment 1 of 4Yong Xiang LewNo ratings yet

- RPMS SY 2021-2022: Annotations and MovsDocument38 pagesRPMS SY 2021-2022: Annotations and MovsLee Ann HerreraNo ratings yet

- Bonifacio V. Romero High School Senior High School DepartmentDocument2 pagesBonifacio V. Romero High School Senior High School DepartmentThons Nacu LisingNo ratings yet

- Self-Regulation and Research Writing Competencies of Senior High School StudentsDocument11 pagesSelf-Regulation and Research Writing Competencies of Senior High School StudentsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- GE6103 Living in The IT Era Midterm Quiz 1 - Attempt ReviewDocument4 pagesGE6103 Living in The IT Era Midterm Quiz 1 - Attempt ReviewChristian TeroNo ratings yet

- Integrating English Context To Different Subject AreaDocument21 pagesIntegrating English Context To Different Subject Areasheryl ann dionicioNo ratings yet

- September 19 - 23, 2022 DLL EIM 12Document3 pagesSeptember 19 - 23, 2022 DLL EIM 12alvin de leon100% (3)

- Engineering Associate Summary Statement BrfinalDocument8 pagesEngineering Associate Summary Statement BrfinalJackNo ratings yet

- Ethical Decision Making and LeadershipDocument11 pagesEthical Decision Making and LeadershipIftikhar AhmedNo ratings yet

- CHN 1stseminarDocument2 pagesCHN 1stseminarAni mathewNo ratings yet

- Writing A Concept PaperDocument2 pagesWriting A Concept PaperJamila Mesha Ordo�ezNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesSharie ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence in Manufacturing PDFDocument12 pagesArtificial Intelligence in Manufacturing PDFFabian OrozcoNo ratings yet

- PR2 CHAP 1 3 SampleDocument21 pagesPR2 CHAP 1 3 Samplehoneyymoreno16No ratings yet

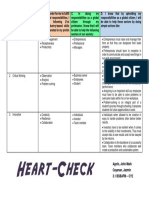

- 3.1bsbafm Cy2 - Heart CheckDocument1 page3.1bsbafm Cy2 - Heart CheckYOFC AEILINNo ratings yet

- CHANGE MANAGEMENT Patterns of ChangeDocument16 pagesCHANGE MANAGEMENT Patterns of Changes wNo ratings yet

- 1 Field-Research-Methods Paluck Cialdini 2014Document18 pages1 Field-Research-Methods Paluck Cialdini 2014Reynard GomezNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Political Science 2022-23Document67 pagesSyllabus Political Science 2022-23helloimnoobymanNo ratings yet

- Rvey/research Project Content: Goal of Survey or Project Excellent Good Fair Poor GradeDocument3 pagesRvey/research Project Content: Goal of Survey or Project Excellent Good Fair Poor Graderoyette ladicaNo ratings yet

- Case 2 FinalDocument18 pagesCase 2 Finalumusulaimu mustafaNo ratings yet

- Mahi AssignmentDocument11 pagesMahi Assignmentyassin eshetuNo ratings yet

- ppst-7 DomainsDocument17 pagesppst-7 DomainsRocelgie JimenezNo ratings yet