Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part14

Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part14

Uploaded by

DCOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part14

Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part14

Uploaded by

DCCopyright:

Available Formats

Practical guide on admissibility criteria

contact with their representative and contrast with N.D. and N.T. v. Spain [GC], §§ 69-79, and the

references therein, where the representative remained in contact with both applicants via

telephone and WhatsApp, and the existence of special circumstances regarding respect for human

rights as defined in the Convention and the Protocols thereto requiring the Court to continue the

examination of the application (Article 37 § 1 in fine)). On the validity of an authority to act, see Aliev

v. Georgia, §§ 44-49; on the authenticity of an application, see Velikova v. Bulgaria, §§ 48-52.

61. As a general rule, minor children are represented before the Court by their parents. The

standing as the natural parent suffices to afford him or her the necessary power to apply to the

Court on the child’s behalf in order to protect the child’s interests also, even—or indeed especially

—if that parent is in conflict with the authorities and criticises their decisions and conduct as not

being consistent with the rights guaranteed by the Convention (Iosub Caras v. Romania, § 21). In any

event, the key criterion in relation to questions of locus standi is the risk that children’s interests

might not be brought to its attention and that they would be denied effective protection of their

Convention rights (Strand Lobben and Others v. Norway [GC], § 157). In cases arising out of disputes

between parents, it is in principle the parent entitled to custody and therefore entrusted with

safeguarding the child’s interests, who has standing to act on the child’s behalf (Hromadka and

Hromadkova v. Russia, no. 22909/10, § 119, 11 December 2014; Y.Y. and Y.Y. v. Russia, § 43).

However, the situation may be different if the Court identifies conflicting interests between a parent

and child in the case brought before it, for example, if serious joint parental child neglect has

occurred (Strand Lobben and Others v. Norway [GC], § 158, and E.M. and Others v. Norway, §§ 64-

65; compare and contrast with Pedersen and Others v. Norway, § 45).

62. Moreover, special considerations may arise in the case of victims of alleged breaches of

Articles 2, 3 and 8 of the Convention at the hands of the national authorities, having regard to the

victims’ vulnerability on account of their age, sex or disability, which rendered them unable to lodge

a complaint on the matter with the Court, due regard also being paid to the connections between

the person lodging the application and the victim. In such cases, applications lodged by individuals

on behalf of the victim(s), even though no valid form of authority was presented, have thus been

declared admissible (Centre for Legal Resources on behalf of Valentin Câmpeanu v. Romania [GC],

§ 103; however, compare and contrast with Lambert and Others v. France [GC], §§ 96-106). See, for

example, İlhan v. Turkey [GC], § 55, where the complaints were brought by the applicant on behalf

of his brother, who had been ill-treated; Y.F. v. Turkey, § 29, where a husband complained that his

wife had been compelled to undergo a gynaecological examination; S.P., D.P. and A.T. v. the United

Kingdom, Commission decision, where a complaint was brought by a solicitor on behalf of children

he had represented in domestic proceedings, in which he had been appointed by the guardian ad

litem; C.N. v. Luxembourg, § 28-33, where the power of attorney had been given by the parents

whose parental authority was later revoked; V.D. and Others v. Russia, §§ 80-84, where an

application was brought by a guardian acting on behalf of minors. See also, by contrast, Lambert and

Others v. France [GC], § 105, where the Court held that the parents of the direct victim, who was

unable to express his wishes regarding a decision to discontinue nutrition and hydration which

allowed him to be kept alive artificially, did not have standing to raise complaints under Articles 2, 3

and 8 of the Convention in his name or on his behalf; and Gard and Others v. the United Kingdom

(dec.), § 63-70, which differed from Lambert and Others since the direct victim was a minor, who

had never been able to express his views or live an independent life, and where the Court discussed

whether the parents of the direct victim had standing to raise complaints under Articles 2 and 5 on

his behalf, but did not come to a final conclusion on this point, given that the issues were also raised

by the applicants on their own behalf.

63. In Blyudik v. Russia (§§ 41-44), relating to the lawfulness of a placement in a closed educational

institution for minors, the Court stated that the applicant was entitled to apply to the Court to

protect the interest of the minor under Article 5 and 8 as regards her placement in the institution:

the daughter was a minor at the time of the events in issue, as well as at the time when the

European Court of Human Rights 20/110 Last update: 31.08.2022

You might also like

- ADR - Case Briefs - ADR - Amit JyotiDocument72 pagesADR - Case Briefs - ADR - Amit JyotiArchitUniyalNo ratings yet

- Aruego v. CA (G.R. No. 112193, March 13, 1996)Document2 pagesAruego v. CA (G.R. No. 112193, March 13, 1996)Lorie Jean Udarbe100% (1)

- 3 (Allowed) PDF Hamalainen V Finland - (2014) 37 BHRC 55Document32 pages3 (Allowed) PDF Hamalainen V Finland - (2014) 37 BHRC 55NurHafizahNasirNo ratings yet

- Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part7Document2 pagesAdmissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part7DCNo ratings yet

- Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part4Document2 pagesAdmissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part4DCNo ratings yet

- Bagtas Vs HonSantos PDFDocument3 pagesBagtas Vs HonSantos PDFIzzyMaxinoNo ratings yet

- Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part8Document2 pagesAdmissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part8DCNo ratings yet

- Omar Alexis Villamizar Gallardo 17291009Document4 pagesOmar Alexis Villamizar Gallardo 17291009Michael SuarezNo ratings yet

- Bagtas Vs SantosDocument3 pagesBagtas Vs SantosJohn Garcia100% (1)

- Magat VsDocument2 pagesMagat VsAustine Clarese VelascoNo ratings yet

- L. Chandran Vs Venkatalakshmi and Anr. On 5 September, 1980 PDFDocument2 pagesL. Chandran Vs Venkatalakshmi and Anr. On 5 September, 1980 PDFmanish.eer2394No ratings yet

- Del Socorro vs. Van WilsemDocument14 pagesDel Socorro vs. Van WilsemLeopoldo, Jr. BlancoNo ratings yet

- Tamargo v. CADocument5 pagesTamargo v. CAMariel RamirezNo ratings yet

- Compile 3Document7 pagesCompile 3Elaine PinedaNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Loreto c. Maramag, Represented by Surviving Spouse Vicenta Pangilinan Maramag, Petitioners, Vs. Eva Verna de Guzman Maramag, Odessa de Guzman Maramag, Karl Brian de Guzman Maramag, Trisha Angelie Maramag,Document2 pagesHeirs of Loreto c. Maramag, Represented by Surviving Spouse Vicenta Pangilinan Maramag, Petitioners, Vs. Eva Verna de Guzman Maramag, Odessa de Guzman Maramag, Karl Brian de Guzman Maramag, Trisha Angelie Maramag,Zach Matthew GalendezNo ratings yet

- Norma A. Del Socorro v. Ernest Johan Van Wilsen, G.R. No. 193707 12.10.2014Document5 pagesNorma A. Del Socorro v. Ernest Johan Van Wilsen, G.R. No. 193707 12.10.2014Gericah RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Rhoer Vs RodriguezDocument2 pagesRhoer Vs Rodriguezcha chaNo ratings yet

- Illegtimate SonDocument15 pagesIllegtimate SonGURMUKH SINGHNo ratings yet

- 2 and 3Document171 pages2 and 3bittersweetlemonsNo ratings yet

- Viran Al Nagapan V Deepa Ap Subramaniam and Other Appeals 2016 1 PDFDocument18 pagesViran Al Nagapan V Deepa Ap Subramaniam and Other Appeals 2016 1 PDFpraveenaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 181132 Heirs of Loreto MaramagDocument14 pagesG.R. No. 181132 Heirs of Loreto MaramagChatNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez vs. GadianeDocument12 pagesRodriguez vs. GadianeMaria Nicole VaneeteeNo ratings yet

- FactsDocument2 pagesFactsNN DDLNo ratings yet

- PFR Tamargo EtcDocument17 pagesPFR Tamargo EtcGuinevere RaymundoNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence - Use of SurnamesDocument10 pagesJurisprudence - Use of SurnamesGean CabreraNo ratings yet

- Maramag vs. MaramagDocument7 pagesMaramag vs. MaramagJustin CebrianNo ratings yet

- Madriñan v. MadriñanDocument2 pagesMadriñan v. MadriñanGerard TayaoNo ratings yet

- Rodriguez vs. GadianeDocument13 pagesRodriguez vs. GadianeMaria Nicole VaneeteeNo ratings yet

- Salientes vs. AbanillaDocument2 pagesSalientes vs. Abanillalunalovesthemoon100% (1)

- Tamargo Vs Court of Appeals Et AlDocument5 pagesTamargo Vs Court of Appeals Et Alandrea ibanezNo ratings yet

- Freedom of Religion South Africa V Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development and Others (GL 2Document12 pagesFreedom of Religion South Africa V Minister of Justice and Constitutional Development and Others (GL 2PoesNo ratings yet

- Digested Case. TooortsDocument15 pagesDigested Case. TooortsReina Gee AbejuelaNo ratings yet

- Motion To Consolidate and Expedite AppealsDocument11 pagesMotion To Consolidate and Expedite AppealsEquality Case FilesNo ratings yet

- Ada Vs BaylonDocument3 pagesAda Vs BaylonMA. TRISHA RAMENTONo ratings yet

- 2020 Civil Cases For VillamilDocument22 pages2020 Civil Cases For VillamilAgot RosarioNo ratings yet

- Case Digest CompleteDocument39 pagesCase Digest CompleteErah SylNo ratings yet

- Baguni vs. PiedadDocument6 pagesBaguni vs. PiedadsuperdaredenNo ratings yet

- GR 154598Document10 pagesGR 154598AM CruzNo ratings yet

- Oposa Vs Factoran FactsDocument30 pagesOposa Vs Factoran FactsMa. Tiffany T. CabigonNo ratings yet

- Death, Marriage and Insolvency of PartiesDocument14 pagesDeath, Marriage and Insolvency of PartiesfaarehaNo ratings yet

- Intestate Succession CasesDocument34 pagesIntestate Succession CasesKylaNo ratings yet

- Except Provided by The Supreme Court: FactsDocument7 pagesExcept Provided by The Supreme Court: Factscarmela salazarNo ratings yet

- CCZ 12-15 - MUDZURU V THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE LEGAL PARL AFFAIRS - 0Document60 pagesCCZ 12-15 - MUDZURU V THE MINISTER OF JUSTICE LEGAL PARL AFFAIRS - 0Malcom GumboNo ratings yet

- 2 Madrinan v. MadrinanDocument9 pages2 Madrinan v. MadrinanRozaiineNo ratings yet

- Case NoteDocument5 pagesCase NotePrakhar RaghuvanshiNo ratings yet

- Persons Doctrine: Renvoi Doctrine (Art. 15-17) Roehr vs. Rodriguez GR No. Date: PonenteDocument2 pagesPersons Doctrine: Renvoi Doctrine (Art. 15-17) Roehr vs. Rodriguez GR No. Date: Ponentenikol crisangNo ratings yet

- 11 Heirs of Loreto MaramagDocument15 pages11 Heirs of Loreto MaramagpulithepogiNo ratings yet

- Admissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part3Document2 pagesAdmissibility - Guide - Eng 31.08.2022 - Part3DCNo ratings yet

- Aruego v. CA, GR 112193Document6 pagesAruego v. CA, GR 112193Anna NicerioNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Loreto C. Maramag vs. Maramag - CivPro - KongDocument3 pagesHeirs of Loreto C. Maramag vs. Maramag - CivPro - KongLouis BelarmaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 85044 June 3, 1992 Macario Tamargo, Celso Tamargo and Aurelia TamargoDocument13 pagesG.R. No. 85044 June 3, 1992 Macario Tamargo, Celso Tamargo and Aurelia TamargoGustavo Fernandez DalenNo ratings yet

- SAntiago Vs Tulfo FullDocument4 pagesSAntiago Vs Tulfo FullWresen AnnNo ratings yet

- Cabanas v. Pilapil, 58 SCRA 94Document9 pagesCabanas v. Pilapil, 58 SCRA 94Vic RabayaNo ratings yet

- Equal Protection For Illegitimate Children - The Supreme Courts SDocument41 pagesEqual Protection For Illegitimate Children - The Supreme Courts SPatricia Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- 02 Heirs of Loreto V de GuzmanDocument6 pages02 Heirs of Loreto V de Guzmansunsetsailor85No ratings yet

- Respondents: Petitioners VsDocument9 pagesRespondents: Petitioners VsJp CoquiaNo ratings yet

- Tonog Versus DaguimolDocument2 pagesTonog Versus DaguimolDiana Sia VillamorNo ratings yet

- Political-Law-Reviewer Case DigestDocument155 pagesPolitical-Law-Reviewer Case Digestshintaroniko100% (2)

- Law of Succession Revision Notes Case Summaries, July 2020Document65 pagesLaw of Succession Revision Notes Case Summaries, July 2020Tatenda MudyanevanaNo ratings yet

- Sid JudgementDocument6 pagesSid JudgementVrinda DwivediNo ratings yet

- Trial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal, Volume 02, Nuremburg 14 November 1945-1 October 1946From EverandTrial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal, Volume 02, Nuremburg 14 November 1945-1 October 1946No ratings yet

- Harrisons Principles of Internal Medicine, 19th EditionDocument8 pagesHarrisons Principles of Internal Medicine, 19th EditionTALBIYAH SABDAH RIZAN TAUPIQ -No ratings yet

- Legends, Folktales and Local Color Fables and Tall TalesDocument3 pagesLegends, Folktales and Local Color Fables and Tall TalesMarc Anthony Manzano0% (2)

- Grade 5 Olympiad: Answer The QuestionsDocument15 pagesGrade 5 Olympiad: Answer The QuestionsVinieysha LoganathanNo ratings yet

- E - L 7 - Risk - Liability in EngineeringDocument45 pagesE - L 7 - Risk - Liability in EngineeringJivan JayNo ratings yet

- Briefmac Chap01-2Document13 pagesBriefmac Chap01-2Bekki VanderlendeNo ratings yet

- 2931 Montreux 1990 (10 Pages)Document10 pages2931 Montreux 1990 (10 Pages)JulianNo ratings yet

- Vetero-Legal WoundsDocument26 pagesVetero-Legal WoundsAhmadx Hassan100% (4)

- CH 13Document123 pagesCH 13Nm TurjaNo ratings yet

- Besr 12 Week 7 Quarter 4Document6 pagesBesr 12 Week 7 Quarter 4Melben ResurreccionNo ratings yet

- Advantages & Disadvantages of ADRDocument2 pagesAdvantages & Disadvantages of ADRAbuzar ZeyaNo ratings yet

- Instant Download Child Development An Active Learning Approach Third Edition PDF Version PDF ScribdDocument41 pagesInstant Download Child Development An Active Learning Approach Third Edition PDF Version PDF Scribdstanley.rodriquez278100% (42)

- Axial Laminar Flow in An Eccentric AnnulDocument2 pagesAxial Laminar Flow in An Eccentric AnnulhugiNo ratings yet

- The Yogas of Enlightenment: A Vedic Astrological Analysis of The Chart of OshoDocument6 pagesThe Yogas of Enlightenment: A Vedic Astrological Analysis of The Chart of OshoLamaCNo ratings yet

- HandOuts For John of SalisburyDocument3 pagesHandOuts For John of SalisburyMelchizedek Beton OmandamNo ratings yet

- Certificates, Certifications, Declarations and Statements: International Standard Banking PracticeDocument1 pageCertificates, Certifications, Declarations and Statements: International Standard Banking PracticeChristous PkNo ratings yet

- Preparation Outline (Informative Speech) : I. Attention Getter II. Iii. IV. V. Stating Established FactsDocument4 pagesPreparation Outline (Informative Speech) : I. Attention Getter II. Iii. IV. V. Stating Established FactsNur AthirahNo ratings yet

- DjvuDocument49 pagesDjvugaud28No ratings yet

- Contemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions Module 9Document5 pagesContemporary Philippine Arts From The Regions Module 9Agatsuma KylineNo ratings yet

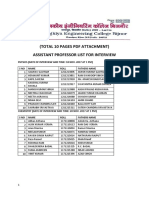

- Candidates List For Interview...Document10 pagesCandidates List For Interview...ajayNo ratings yet

- DLL Q1 Lesson 4 Saturated and UnsaturatedDocument3 pagesDLL Q1 Lesson 4 Saturated and UnsaturatedMa. Elizabeth CusiNo ratings yet

- Orquia, Anndhrea S. BSA 32 EssayDocument5 pagesOrquia, Anndhrea S. BSA 32 EssayClint RoblesNo ratings yet

- A Project SynopsisDocument25 pagesA Project SynopsisAnkit SharmaNo ratings yet

- Drum Boiler ModelingDocument18 pagesDrum Boiler ModelingAhmad RahanNo ratings yet

- Straight Lines - WorkbookDocument37 pagesStraight Lines - WorkbookKarthikeyanNo ratings yet

- PrizmDocument32 pagesPrizmJer100% (1)

- A Critique of John Mbiti's Undestanding of The African Concept of TimeDocument13 pagesA Critique of John Mbiti's Undestanding of The African Concept of Timerodrigo cornejoNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S187705092102425X MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S187705092102425X MainMichael Angelo AlbaoNo ratings yet

- Final Research PaperDocument17 pagesFinal Research PaperMohamed BassuoniNo ratings yet

- Language and Society - QuestionsDocument2 pagesLanguage and Society - QuestionsMihai Ovidiu100% (2)