Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Page 35 45 2021 13019

Uploaded by

Ar Aayush GoelOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Page 35 45 2021 13019

Uploaded by

Ar Aayush GoelCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Environmental Sciences and Resources Management

Volume 13, Number 1, 2021

ISSN: 2277-0097

http://www.cenresinjournals.com

A STUDY OF WAYFINDING AND CIRCULATION IN MALL DESIGN

Ihunwo Wisdom Chiyeruigo & Anthony Dornubari Enwin

Department of Architecture

Faculty of Environmental Sciences

Rivers State University, Npkolu, Oruworukwo, Port Harcourt

Email: ihunwowisdom@gmail.com, PG.2018/00550

ABSTRACT

Malls are places where the influx of people is on the high side especially during

peaks periods or festive seasons. Therefore, in other to avoid stampede during

exit and entering of mall design, is imperative that every section of the mall

should have a defining way that can allow easy identification. To this end,

proper movement within and around this facility should be kept simple and

should be made easy for users to find their way through this facility. This

Journal therefore seeks to examine and highlight through the use of

secondary data the possible ways wayfinding and circulation can be

enhanced in mall designs.

Keywords: Wayfinding, Circulation,

Circulation, Mall Design, Movement.

INTRODUCTION

It is obvious and potential that one powerful influence on

wayfinding and circulation behavior is the degree of familiarity an

individual has with a given setting. If familiarity is increased to

sufficient levels, initial difficulties in orientation may be overcome.

This will enable efforts to be directed toward increasing the

knowledge level of naïve users of a setting. On the contrary,

familiarity alone does not explain disorientation, then other factors,

such as visual or spatial features of the environment, ought to be

considered Weisman,(1981).,

Wayfinding

Wayfinding as an idea has been in presence since the sixteenth

century. Initially, it was referred to by the term “wayfaring,” which

means travelling on foot to a certain destination (Arthur & Passini,

1992). Through the years, design professionals, architects, urban

planners, graphic designers and environmental psychologists have

developed the term wayfinding to describe the ‘navigation of one’s

environment’. Wayfinding is ceaselessly developing dependent on

35| Ihunwo W. C. et. al

A Study of Wayfinding and Circulation in Mall Design

personal experience and evidence dependent on the utilization

and control of complex conditions by end-users. (Oyelola, 2014)

Wayfinding is the propensity to get to desired destinations in the

natural and built environment. (Passini, Rainville, Marchand, &

Joanette, 1998). Kelvin Lynch (1960), published his first book ‘The

Image of the City’ of which he described wayfinding from the

urban perspective, using concepts such as ‘spatial orientation’ and

‘cognitive mapping.

Oyelola, 2014) Lynch in Oyelola (2014) further explains that the

experience of wayfinding are based on environmental

components such as paths, edges, landmarks, nodes and districts.

These concepts and components form the basis of wayfinding

design theory as it is presently utilized. Architectural wayfinding

configuration addresses-built components, including spatial

arranging, enunciation of form-giving highlights, circulation

frameworks and environmental communication. Wayfinding

configuration is integral to universal design since it advances

simple comprehension and utilization of built elements at all scales.

Successful wayfinding design allows people to attain the following:

1. Determination of location within a setting (building or urban

setting)

2. Determination of prospective destination

3. Development of a movement plan (from location to destination)

4. Execute the plan and negotiate any required changes (Mayor’s

Office for People with Disabilities, 2001) in (Hunter, 2010).

Passini et al, (1998) posits that wayfinding is composed of three

interrelated processes:

1. Decision-making and the development of a plan of action

2. Decision executing transforming the plan into action and

behaviors at the right place and time.

3. Information gathering and treatment which sustains the two

decision-related processes. (Passini, Rainville, Marchand, &

Joanette, 1998)

Passini graphically illustrated three levels of decision making using

a scenario of moving from a location x to “Turtle Atoll”. Here, he

36| Ihunwo W. C. et. al

Journal of Environmental Sciences and Resources Management

Volume 13, Number 1, 2021

breaks down the series of choices to be processed and actions to

make based on the above three decision making processes. This is

illustrated here. The trend of thought and decision-making

processes is evident in everyday activities – decision to visit a

museum, decision on what exhibits to visit, decision of museum

curator on the proposed paths to be followed during exhibitions,

movement plans, and a lot more.

Lindberg, and Mantyla (1983) found that accuracy in locating

“building targets” was positively correlated with familiarity and

with “free-viewing-access.” When we move about in a familiar

environment we seldom experience disorientation. We also seem

to be able to learn new spatial facts with little difficulty. This may

be the case in an unfamiliar environment if we possess a legible

map and are skilled at using it. Map by direct observations is an

automated process not requiring cognitive resources to any great

extent (Moeser, 1988). Recognition plays an important role in

legibility and orientation. Recognition of places is not possible

unless the environment is somewhat familiar. Maps, sign posts, and

other media may play an important role for orientation in

unfamiliar environments. People rely on numerous types of

environmental information to find their way within buildings.

Weisman (1981) developed four groups of environmental

variables thought to be influential on wayfinding:

(a) Visual access to familiar cues or landmarks with in or exterior to

a building,

(b) The degree of architectural differentiation between different

areas of a building that can aid recall, and hence orientation,

(c) the use of signs and room numbers to provide identification or

directional information, and

(d) Building configuration, which can influence the ease with

which one can comprehend the overall layout of the building.

People find their way in complex settings by trying to

understand what the setting contains and how it is organized.

To form a mental map of the setting, spatial clues must be

identified. Among the basic building blocks of cognitive

mapping are spatial entities. Distinctiveness can be achieved by

the for man volume of the space that define architectural and

37| Ihunwo W. C. et. al

A Study of Wayfinding and Circulation in Mall Design

decorative elements, and by the use of finishes, light, colors, and

graphics (Arthur & Passini). Passini, Rainville, Marchand, and

Joanette (1998) emphasize the importance of distinguishing a

zone; they suggest that a zone with a strong character may

favor a certain spatial identification, if only in the sense of being

somewhere distinct. It is assumed that most architectural

settings and larger scale environments are too extensive to be

perceived in their entirety from any one location. Wright,

Lickorish, and Hull (1993) state that finding a particular

destination can be difficult in many modern building complexes,

where the corridors on different floors can look very much alike.

In those circumstances, information regarding specific locations,

spatial relationships among those locations, and those locations

in relationship to the rest of the building must be stored easily

in one’s head.

Principles of Wayfinding

Downs and Stea (1973) in Farr, Kleinschmidt, Yarlagadda, &

Mengersen, 2012 proposed that wayfinding could be broken

down into a four-step process comprising:

1. Orientation: The ability of a user to find out where they are with

respect to nearby markers and the required destination

2. Route Selection: Choosing a route that will eventually lead to the

desired destination.

3. Route Control: The constant control and confirmation that the

individual is following the selected route.

4. Recognition of Destination: The individual’s ability to realize that

they have reached the desired destination. (Farr, Kleinschmidt,

Yarlagadda, & Mengersen, 2012).

It is on the back drop of the above that the principles of wayfinding

were developed and these principles as presented here comes

from both the research of museum exhibits and the study of

environmental psychologists, cognitive scientists, and others who

study how humans represent and navigate in the physical

environment; (mfoltz, 1998). As listed in the International Health

Facilities Guidelines, there are eight (8) wayfinding principles these

are thus listed and explained as follows:

38| Ihunwo W. C. et. al

Journal of Environmental Sciences and Resources Management

Volume 13, Number 1, 2021

1. Create an Identity at Each Location,

Location, Different from all others:

spaces should be different from others in an overall design layout

as this aid in recognition and overall cognitive mapping of position

and orientation with respect to the overall layout of the design.

This principle indicates that every place should function, to some

extent, as a landmark – a recognizable point of reference in the

larger space. (mfoltz, 1998) This principle was deduced from the

Research work of Arthur and Passini (Arthur and Passini 1992),

where the notions of ‘identity’ and ‘equivalence’ for speaking of

perception of places were introduced. They went further to clarify

that personality is the thing that makes one piece of a space

discernable from another, and comparability is the thing that

enables spaces to be gathered by their regular traits.

2. Use Landmarks to Provide Orientation Cues and Memorable

Locations: Landmarks serve two useful purposes. The first is as an

orientation cue; the second is as an especially memorable location.

While the former enables the navigator or user of a space to

identify his current location, he can say something about where he

is, and which way he is facing in the space he shares with the

landmark (Locational Orientation). The later creates a shared

vocabulary platform for which verbal and written descriptions of

locations or routes can be achieved. ‘Landmarks associated with

decision points, where the navigator must choose which path of

many to follow, are especially useful as they make the location and

the associated decision more.

3. Create Well-

Well-Structured Paths: For a path to be well-well-structured,

they must possess a set of characteristics such as: continuous;

having clear headings (beginning, middle and end) when viewed

in each direction (mfoltz, 1998). They should confirm progress and

distance to their destination along their length; and a navigator

should easily understand which direction he is moving along the

path by its ‘directionality’ or “sidedness”. mfoltz, (1998)

4. Create Regions of Differing Visual Character: This principle deals

with the division of spaces into regions of distinct set of visual

attributes (colors, textures, forms, shapes, and others) to assist in

wayfinding. The character that sets a space apart can be some

39| Ihunwo W. C. et. al

A Study of Wayfinding and Circulation in Mall Design

aspect of its visual appearance, a distinction in function or use, or

some attribute of its content that is consistently maintained within

the region of space but not without. Regions of spaces in buildings

may not have readily defined boundaries as they tend to overlap,

or their extent may be in some part subjective; but there is a

generally agreed space said to be within the region of space, and

a surrounding area said to be outside it. Mfoltz, (1998).

5. Minimal Navigation Choice for Users: If there is a story to tell,

spaces should be designed so that it is coherent for every route the

navigator might take. The basic story should be communicated by

every path the navigator can take through the space.

Opportunities for detours, side-tours, and exploration can branch

off the main path, eventually returning to resume the main story

mfoltz, (1998).

6. Use of Sight Lines to Reveal what is ahead: This principle deals

with creating a visually accessible space(s) for which view in a

distinct direction is made extensive and tailored with a purpose to

attract visitors to that direction. In an exhibit space, in which the

first-time visitor has uncertain expectations as to its extent and

purpose, sight lines are valuable means of giving enough

information about what is ahead to encourage the visitor to move

farther. Sight lines give long narrow samples of unfamiliar spaces.

To make a sight line more interesting, the design can adopt a

strategy of creating an “attractor” – a goal to navigate toward. This

might be some feature (sculpture, art work, and others) that is

striking and unusual (mfoltz, 1998).

7. Provide Signs at Decision Points to Help Wayfinding decisions:

Signs should be placed, where necessary, at decision points on the

floor layout (most preferably, the use of sculptures, or multi

directional arrow heads or beacons). Decision points are points

where the visitor must make a wayfinding decision (whether to

continue along a particular route or change direction). (mfoltz,

1998)

8. Use Survey View (Navigational Floor maps or Vistas): create floor

maps which visitors will use as a navigational aid. Is places the

40| Ihunwo W. C. et. al

Journal of Environmental Sciences and Resources Management

Volume 13, Number 1, 2021

entire space within the navigator’s view, and several kinds of

judgements can be made readily. Survey views can also provide the

basis for the visitor’s mental map; and the mental map, primed with

the image of his environment, can be augmented readily with

experience gained from actual navigation in the space. (mfoltz,

1998)

The above set of principles can thus be classified into two main

categories - during design and post-design; and these intrinsically

affect the circulation design choices and outcomes. Principles such

as – creation of distinct spatial identities, Use of Land marks,

Creation of differing visual characters, Minimal Navigational

Choices, Use of Sight lines to reveal what is ahead; can be

integrated and achieved during the design stages. The provision of

signs at decision points as well as use of survey views are

achievable post design.

This thesis will thus explore the adoption of the principles of

wayfinding that are applicable during design stages as highlighted

above in a bid to create more navigable spaces which will thus

greatly enhance visitor movement in museum spaces.

Visitor Circulation in Relation to Orientation and Wayfinding: The

successful use of a complex of spaces is directly influenced by the

factors of orientation and wayfinding. There are three major

elements to visitor orientation and circulation: Conceptual

orientation, wayfinding, and circulation Bit good, (2010).

Conceptual orientation (also known as “thematic” orientation)

includes an awareness and understanding of the themes and

subject matter organization of the facility; although visitor

expectation and prior experiences play a key role in conceptual

orientation. Visitor orientation and circulation is related to all

aspects of the museum experience. (Bitgood, 2010).

Lack of orientation information causes people to feel disoriented

which leads them to an inability to situate themselves within the

environment and incapability of having or developing a plan in

order to reach their destination. (Arthur and passini, 1992, p.225 in

Ash, 2005). Orientation will influence the circulation patterns of

41| Ihunwo W. C. et. al

A Study of Wayfinding and Circulation in Mall Design

visitors and circulation designs influence the users’ orientation

(Bitgood, 2010).

Charpman and Grant, (2002) in Ash, (2005) describes wayfinding

as follows:

“Wayfinding is behavior. Successful wayfinding involves knowing

where you are, knowing your destination, knowing and following

the best route (or at least a serviceable route) to your

ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN CONSIDERATIONS TO ACHIEVING

OPTIMAL SPECIAL ORGANIZATION AND RELATIONSHIP.

• Spatial Planning.

The planning and layout of a building forms the foundation for all

other wayfinding elements. Spatial planning involves identifying,

grouping and linking spaces.

Planning a layout involves the identification of spatial units and

understanding their purpose, function and relationships to other

units. Based on these relationships and functions, units can be

grouped into zones of common function/ identity.

Understanding the logical progression of, and relationships

between spaces will determine the circulation system and is an

important aspect in creating an effective wayfinding system.

Directional signs can only do so much to assist users in illogical,

complicated routes. The goal is to keep circulation systems simple

and legible to a user by reducing the number of decision points,

maximizing visual access and minimizing any change in level and

directions in between landmark and nodes.

Comprehending relationships between zones, including the

physical and visual access required between them, allows the

qualities required in the circulation paths that connect spaces to be

explored. For example, clear lines of sight from car parks to

entrances and from entrances to lift foyers or reception counters

helps guide the consumer to their destination or to information

that will further assist the consumer to navigate the health facility.

These visual access requirements will therefore impact how these

42| Ihunwo W. C. et. al

Journal of Environmental Sciences and Resources Management

Volume 13, Number 1, 2021

zones are laid out and connected, for example how open and

direct the path is.

Different methods can be used to plan library space and it will

attain the openness, flow and functionality.

Below are certain pattern that can be adopted to attain optimal

spatial efficiency.

Fig 1: Chain Spatial Pattern. Fig. 2. Window spatial

pattern

Chain (A): and window pattern (B): (B) The main aim of the chain

pattern is to allow visitors to navigate regarding their interest in

displayed books or materials.

Window (B): From the central point, visitors can move towards the

rooms according to their interests

Fig. 3: Central Spatial Pattern: Fig 4: Block

Spatial Pattern

Central:

Central Describing the collection in the center, the aim is to allow

visitors to see it from different viewpoints

Block: It provides navigation voluntarily and in a random fashion

43| Ihunwo W. C. et. al

A Study of Wayfinding and Circulation in Mall Design

Fig 5: Brush Spatial Pattern: The main aim is to allow visitors to

move through the rooms voluntarily.

Source: Erbay (1992) in Ash (2005).

The above are conceptual patterns which if it is followed it can

enhance way finding and circulation in the mall. These patterns

will enhance and make movement easy.

CONCLUSION

Circulation and wayfinding are necessities in the design of a mall

that cannot be neglected. A functional design mall design must be

arrayed in such a way that flow and movement if people must be

directional and must enhance way finding. All requirement to

achieve this purpose must be conceptually thought about because

it is a factor that can be hardly corrected when design is already in

place. One basic way of keeping this purpose optimized is o ensure

that openness in layout of plan and arrangement of space is

adopted, use of self-directional means i.e the use of synages should

also be imbibe where necessary. Therefore, this paper is highly

recommended as it aids and proffers solution to achieving a

sustainability mall design. This paper is also subjected for further

reviews and analysis.

44| Ihunwo W. C. et. al

Journal of Environmental Sciences and Resources Management

Volume 13, Number 1, 2021

REFERENCE.

Arthur,P.,&Passini,R. (1992). Wayfinding: People, signs and

architecture. NewYork:

Bronzaft, A., & Dobrow, S. (1984). Improving transit information.

Journal of Environmental Systems, 13, 365-375.

Canter,D.V. (1996). Wayfinding and signposting: Penance or

prosthesis. InD.V.Canter (Ed.), Psychology in action (pp. 139-

155). San Diego: Academic Press.

Evans,G.W,Smith, C, & Pezdek,K. (1982). Cognitive maps and urban

forms. Journal of the American Planning Association, 48,

232-244.

Galper,N.G.(1987). Daedalus and the modern mall: The influence

of shopping Centre architecture and design on wayfinding

and shopping behavior. Unpublished master’s thesis,

Pennsylvania State University.

Garling,T,Lindberg,E.,&Mantyla,T. (1983). Orientation in buildings:

Effects off Amiliarity, visual access, and orientation aids.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 68, 177-186.

McGrawHill. Bolen, W. H. (1988). Contemporary retailing. New

York: Prentice Hall.

ElBaser, A. (n.d.). Chapter One - Understanding Wayfinding:

Perception & Cognitive Mapping. Retrieved from CPAS -

CENTRE FOR ARCHITECTURAL PLANNING STUDIES:

www.cpas-egypt.com/pdf/Abd_ElBaser/M.SC/002.pdf

Elottol, R., & Bahauddin, A. (2011). A Competitive Study on the

Interior Environment and the Interior Circulation Design of

Malaysian Museums and Elderly Satisfaction.

doi:10.5539/jsd.v4n3p223.

45| Ihunwo W. C. et. al

You might also like

- Spatial OrientationDocument11 pagesSpatial OrientationCatalina Tapia100% (1)

- A Computational Approach For Evaluating The Facilitation of Wayfinding in EnvironmentsDocument9 pagesA Computational Approach For Evaluating The Facilitation of Wayfinding in Environmentsgökra ayhanNo ratings yet

- MT SWF WayfindingDesign PDFDocument10 pagesMT SWF WayfindingDesign PDFGiorgio Calandri100% (1)

- Report On Le'corb 'S PrincipleDocument7 pagesReport On Le'corb 'S Principleaesha daveNo ratings yet

- Architectural Way FindingDocument8 pagesArchitectural Way Findingoriendoschoolofmagic100% (1)

- What Is Wayfinding? - The WayfindingDocument2 pagesWhat Is Wayfinding? - The WayfindingruizcastellanoNo ratings yet

- Up The Down Staircase Wayfinding Strategies in Multi-Level BuildingsDocument16 pagesUp The Down Staircase Wayfinding Strategies in Multi-Level BuildingsMusliminNo ratings yet

- The Architectural Spaces and Their Psych PDFDocument12 pagesThe Architectural Spaces and Their Psych PDFKathrine DisuzaNo ratings yet

- Urban Form and Wayfinding: Review of Cognitive and Spatial Knowledge For Individual S' NavigationDocument14 pagesUrban Form and Wayfinding: Review of Cognitive and Spatial Knowledge For Individual S' NavigationMihaela MarinceanNo ratings yet

- Constructing Spatial Meaning: Spatial Affordances in Museum DesignDocument24 pagesConstructing Spatial Meaning: Spatial Affordances in Museum DesignVirginie Convence ArulthasNo ratings yet

- Wayfinding Design Logic, Application and Some Thoughts On UniversalityDocument13 pagesWayfinding Design Logic, Application and Some Thoughts On UniversalityMusliminNo ratings yet

- Lu 和 Ye - 2019 - Can people memorize multilevel building as volumetDocument18 pagesLu 和 Ye - 2019 - Can people memorize multilevel building as volumetqiangdan96No ratings yet

- Email: Rrj94@aber - Ac.ukDocument22 pagesEmail: Rrj94@aber - Ac.ukRaghvi KabraNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Wayfinding by Christopher KuehDocument11 pagesThesis On Wayfinding by Christopher KuehpoongaarNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Mapping in Spaces For Public Use: Rishab Chopra, Gaurab Das MahapatraDocument5 pagesCognitive Mapping in Spaces For Public Use: Rishab Chopra, Gaurab Das MahapatraChethan GowdaNo ratings yet

- Evans 2011 Walking InterviewDocument10 pagesEvans 2011 Walking Interviewhasblady19No ratings yet

- Spatial Cognition in Architectural Design Anticipating User Behavior, Layout Legibility, and Route Instructions in The Planning ProcessDocument39 pagesSpatial Cognition in Architectural Design Anticipating User Behavior, Layout Legibility, and Route Instructions in The Planning Processnensi gyNo ratings yet

- Campisi 2020Document16 pagesCampisi 2020DrOmar ArchNo ratings yet

- Landscape Design and Cognitive PsychologyDocument3 pagesLandscape Design and Cognitive PsychologyuhiuhiuNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Spatial Ability and Map Types On Way Finding:A Case of National Museum Ofnatural Science TaiwanDocument20 pagesThe Effect of Spatial Ability and Map Types On Way Finding:A Case of National Museum Ofnatural Science TaiwanwangNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Technology: Tours and Maps Operations As Movement Mechanism in Indoor WayfindingDocument10 pagesInternational Journal of Technology: Tours and Maps Operations As Movement Mechanism in Indoor WayfindingDcxyNo ratings yet

- Towards A Successful Sustainable Public Space: A Parametrical Approach To Strengthen Sense of Place Identity (An Egyptian Case Study)Document22 pagesTowards A Successful Sustainable Public Space: A Parametrical Approach To Strengthen Sense of Place Identity (An Egyptian Case Study)Shaimaa MagdiNo ratings yet

- Wayfinding A Simple Concept, A Complex ProcessDocument29 pagesWayfinding A Simple Concept, A Complex ProcessZainab Aljboori100% (1)

- The Dynamic Nature of Cognition During Wayfinding: Hugo J. Spiers, Eleanor A. MaguireDocument18 pagesThe Dynamic Nature of Cognition During Wayfinding: Hugo J. Spiers, Eleanor A. MaguiresafiradhaNo ratings yet

- The Relationship between Imageability and Form in Architecture: Considerations for Design of Imageable Landmark Buildings in CitiesPaul Mwangi Maringa & Philip Okello OchiengJomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, P.O. Box 62000 – 00200, Nairobi, Kenya,Email: pmmaringa@yahoo.co.uk, pmcokello@yahoo.co.uk or davihunky@yahoo.com, published in the African Journal of Design and Construction (AJDC), Vol 1 (1) 2006Document9 pagesThe Relationship between Imageability and Form in Architecture: Considerations for Design of Imageable Landmark Buildings in CitiesPaul Mwangi Maringa & Philip Okello OchiengJomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology, P.O. Box 62000 – 00200, Nairobi, Kenya,Email: pmmaringa@yahoo.co.uk, pmcokello@yahoo.co.uk or davihunky@yahoo.com, published in the African Journal of Design and Construction (AJDC), Vol 1 (1) 2006Paul Mwangi Maringa100% (2)

- From Urban Experiences To Architectural NarrativesDocument11 pagesFrom Urban Experiences To Architectural NarrativesAA Ayu AnastasyaNo ratings yet

- Group - 8: Way-Finding in Virtual EnvironmentDocument25 pagesGroup - 8: Way-Finding in Virtual Environmentshikhar guptaNo ratings yet

- Measuring The Unmeasurable Urban Design Qualities Related To WalkabilityDocument21 pagesMeasuring The Unmeasurable Urban Design Qualities Related To WalkabilityJose Francisco RomeroNo ratings yet

- Prepared By:-Shifa Goyal B.Arch 2016-21 Roll No. 22 Faculty of Architeture Urban Planner and AuthorDocument14 pagesPrepared By:-Shifa Goyal B.Arch 2016-21 Roll No. 22 Faculty of Architeture Urban Planner and AuthorMonishaNo ratings yet

- Basic Concept of Urban DesignDocument2 pagesBasic Concept of Urban DesignyoungsterjoeyyyNo ratings yet

- Urban Space and Its Information FieldDocument22 pagesUrban Space and Its Information FieldDan Nicolae AgentNo ratings yet

- Working Paper - 1005Document17 pagesWorking Paper - 1005OrianaFernandezNo ratings yet

- The Field Trip As Part of Spatial (Architectural) Design Art ClassesDocument14 pagesThe Field Trip As Part of Spatial (Architectural) Design Art ClassesNarjess BayarNo ratings yet

- RK - Cognitive MapsDocument19 pagesRK - Cognitive MapsTanya Kim MehraNo ratings yet

- Spatial Forms and Signage in Wayfinding Decision Points For Hospital Outpatient ServicesDocument9 pagesSpatial Forms and Signage in Wayfinding Decision Points For Hospital Outpatient Servicesgökra ayhanNo ratings yet

- Hlscher2009 HDocument12 pagesHlscher2009 HannaNo ratings yet

- Kai-Florian Richter, Stephan Winter (Auth.) - Landmarks - GIScience For Intelligent Services-Springer International Publishing (2014)Document233 pagesKai-Florian Richter, Stephan Winter (Auth.) - Landmarks - GIScience For Intelligent Services-Springer International Publishing (2014)Sri Utami PurwaningatiNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Intro ModuleDocument14 pagesUnit 1 - Intro Modulezainab444No ratings yet

- Journal of Transport Geography 87 (2020) 102778Document16 pagesJournal of Transport Geography 87 (2020) 102778Ram TulasiNo ratings yet

- Wayfinding in HospitalsDocument25 pagesWayfinding in Hospitalsedmund chumo100% (1)

- HILARIO proposalRMADocument4 pagesHILARIO proposalRMARom Reyes Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- QuizDocument5 pagesQuizZALINE MAE REBLORANo ratings yet

- Cheirchanteri 2021 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1203 032003Document10 pagesCheirchanteri 2021 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 1203 032003gökra ayhanNo ratings yet

- Task 3 - Annotated BibliographyDocument4 pagesTask 3 - Annotated BibliographyDhananjaniNo ratings yet

- Urban Visual Intelligence Studying Cities With Artificial Intelligence and Street-Level ImageryDocument23 pagesUrban Visual Intelligence Studying Cities With Artificial Intelligence and Street-Level ImageryRafael MazoniNo ratings yet

- RRL 1Document19 pagesRRL 1Xyra Mae PugongNo ratings yet

- RP - 12 04 2021 - Final - RahulDocument23 pagesRP - 12 04 2021 - Final - RahulBATMANNo ratings yet

- 1.4.2. Sense of Place TheoryDocument11 pages1.4.2. Sense of Place TheoryCheryl GetongoNo ratings yet

- Spatial Cognition The Role of Landmark Route and SDocument11 pagesSpatial Cognition The Role of Landmark Route and SRegret WhistleNo ratings yet

- Ecaade2013 178.contentDocument10 pagesEcaade2013 178.contentsevanscesNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Image of The CityDocument10 pagesRethinking Image of The CityAzizah Adeniya RNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Attributes Affecting Urban Open Space Design and Their Environmental ImplicationsDocument11 pagesAn Analysis of Attributes Affecting Urban Open Space Design and Their Environmental Implicationsbru.ferNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology: Submitted To: Ar. Arqam KhanDocument5 pagesResearch Methodology: Submitted To: Ar. Arqam KhanMalik MussaNo ratings yet

- Walking Methods in Landscape ResearchDocument9 pagesWalking Methods in Landscape ResearchEquis E EleNo ratings yet

- See Fare Into Distance) : Professor Per Mollerup's 9 Wayfinding StrategiesDocument16 pagesSee Fare Into Distance) : Professor Per Mollerup's 9 Wayfinding StrategiesMihaela MarinceanNo ratings yet

- Urban Design & Community Planning: School of ArchitectureDocument5 pagesUrban Design & Community Planning: School of ArchitectureOcirej OrtsacNo ratings yet

- Perceptual Dimension Summary by ArnavDocument6 pagesPerceptual Dimension Summary by Arnavarnav saikiaNo ratings yet

- Responsive Environment Grp. 9Document23 pagesResponsive Environment Grp. 9May Rose ParagasNo ratings yet

- Design of Supporting Systems for Life in Outer Space: A Design Perspective on Space Missions Near Earth and BeyondFrom EverandDesign of Supporting Systems for Life in Outer Space: A Design Perspective on Space Missions Near Earth and BeyondNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Suburbs: Morphological and Network Analysis ReviewFrom EverandRethinking Suburbs: Morphological and Network Analysis ReviewNo ratings yet

- Conferenceobject 93516Document10 pagesConferenceobject 93516Ar Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- Industrial Tourism When The Industry Becomes A Chance For TourismDocument9 pagesIndustrial Tourism When The Industry Becomes A Chance For TourismAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- Industrial & Business Park Design GuidelinesDocument22 pagesIndustrial & Business Park Design GuidelinesAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- WHI Brochure 2022 - Classic Resort CollectionDocument23 pagesWHI Brochure 2022 - Classic Resort CollectionAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- Japan International Cooperation Agency: NewsletterDocument16 pagesJapan International Cooperation Agency: NewsletterAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- Decoding Finn Juhl's Egyptian Chair - Workshop - BriefDocument5 pagesDecoding Finn Juhl's Egyptian Chair - Workshop - BriefAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- 169 172, Tesma407, IJEASTDocument4 pages169 172, Tesma407, IJEASTAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- Guided By:-Presented By: - Prof. P.M. Nemade Amit Maurya (B.E.) CivilDocument30 pagesGuided By:-Presented By: - Prof. P.M. Nemade Amit Maurya (B.E.) CivilAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- History of Architecture - Gate Architecture - Study MaterialDocument12 pagesHistory of Architecture - Gate Architecture - Study MaterialAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

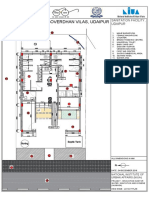

- Public Toilets at Goverdhan Vilas, UdaipurDocument1 pagePublic Toilets at Goverdhan Vilas, UdaipurAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- 12-A Review of Urban (Lalit Batra)Document8 pages12-A Review of Urban (Lalit Batra)Ar Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- URR - Ved Mittal PDFDocument41 pagesURR - Ved Mittal PDFAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- Town Planning in India - Ancient Age - Med PDFDocument22 pagesTown Planning in India - Ancient Age - Med PDFAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- Buildings: DefinitionsDocument31 pagesBuildings: DefinitionsAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- Housing Projects in SCP - 60 CitiesDocument3 pagesHousing Projects in SCP - 60 CitiesAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- Street Lights: PacerDocument1 pageStreet Lights: PacerAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- 4050 - Tansy FlowerDocument1 page4050 - Tansy FlowerAr Aayush GoelNo ratings yet

- (Common Case) (Objective Case) Inf (In Any Form) 0 (Bare Infinitive)Document5 pages(Common Case) (Objective Case) Inf (In Any Form) 0 (Bare Infinitive)Ліліана БортюкNo ratings yet

- LDself ScreeningDocument2 pagesLDself ScreeningImron MuzakkiNo ratings yet

- Tcallp Group 1Document51 pagesTcallp Group 1KEMPIS, Jane Christine PearlNo ratings yet

- The Five Minds of A ManagerDocument8 pagesThe Five Minds of A ManagerAashutosh PandeyNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan Music 1Document6 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan Music 1Michelle Dang-iw100% (1)

- NSTP 2.3.2-Information Sheet TeamBuildingDocument2 pagesNSTP 2.3.2-Information Sheet TeamBuildingVeraniceNo ratings yet

- Wednesday June 10Document3 pagesWednesday June 10Goh Geok CherNo ratings yet

- DLL English Aug 29-Sept 2Document2 pagesDLL English Aug 29-Sept 2IvanAbandoNo ratings yet

- Improving Fluency in Young Readers - Fluency InstructionDocument4 pagesImproving Fluency in Young Readers - Fluency InstructionPearl MayMayNo ratings yet

- Ila Standards RatingsDocument9 pagesIla Standards Ratingsapi-300378538No ratings yet

- Multi Agent ApplicationsDocument384 pagesMulti Agent ApplicationsJhonNo ratings yet

- HabitsDocument16 pagesHabitsluciane thomasNo ratings yet

- Grade 10 Arts Most Essential Learning Competencies MELCsDocument7 pagesGrade 10 Arts Most Essential Learning Competencies MELCsLanie BadayNo ratings yet

- Memorization Approach To Quantum Associative Memory Inspired by The Natural Phenomenon of BrainDocument6 pagesMemorization Approach To Quantum Associative Memory Inspired by The Natural Phenomenon of BrainAlpha BeetaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosing Managerial Characteristics: Michael DellDocument1 pageDiagnosing Managerial Characteristics: Michael DellVirendar SinghNo ratings yet

- Types of Speech PresentationDocument23 pagesTypes of Speech PresentationAndrea GeilNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan in English For Grade 10 Rizal January 14 2016Document3 pagesLesson Plan in English For Grade 10 Rizal January 14 2016elle celesteNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology in Architecture: Defining Experiential ParametersDocument7 pagesPhenomenology in Architecture: Defining Experiential ParametersanashwaraNo ratings yet

- ALS2 Syllabus Students ReferenceDocument2 pagesALS2 Syllabus Students Referenceluis gonzalesNo ratings yet

- GMAT CAT Critical ReasoningDocument2 pagesGMAT CAT Critical ReasoningVishnu RajNo ratings yet

- Transkrip Nilai EnglishDocument32 pagesTranskrip Nilai EnglishDian MahendraNo ratings yet

- Team Dynamics at WorkDocument1 pageTeam Dynamics at Workshekhy123No ratings yet

- The Goldlist Method in A Nutshell Language MentoringDocument36 pagesThe Goldlist Method in A Nutshell Language MentoringGianreds100% (2)

- 8.he Couldn't Help - With ThemDocument3 pages8.he Couldn't Help - With ThemAlexNo ratings yet

- Discourse Analysis Assignment Topic: Substitution: Submitted To Ms. Fizza AslamDocument5 pagesDiscourse Analysis Assignment Topic: Substitution: Submitted To Ms. Fizza AslamNaveen ZahraNo ratings yet

- Editha F. Munoz: Daily Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesEditha F. Munoz: Daily Lesson PlanEstrelita SantiagoNo ratings yet

- COMPREHENSIVE SCHOOL SPORTS PROGRAM For CebuDocument11 pagesCOMPREHENSIVE SCHOOL SPORTS PROGRAM For CebuThelma SalvacionNo ratings yet

- Study Hacks On CampusDocument11 pagesStudy Hacks On Campusbetafilip6910No ratings yet

- Proposal Writing NotesDocument13 pagesProposal Writing NotesJohn Ochuro100% (1)

- Ma Psy SyllabusDocument37 pagesMa Psy SyllabusManali VermaNo ratings yet