Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jcalderi Sec1 Pos0 PDF

Uploaded by

Siti sholekhaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jcalderi Sec1 Pos0 PDF

Uploaded by

Siti sholekhaCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/6494030

An Empirical Examination of the Stage Theory of Grief

Article in JAMA The Journal of the American Medical Association · March 2007

DOI: 10.1001/jama.297.7.716 · Source: PubMed

CITATIONS READS

513 4,610

4 authors, including:

Baohui Zhang Susan D Block

Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Brighsm and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School

174 PUBLICATIONS 7,427 CITATIONS 275 PUBLICATIONS 24,967 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Holly G Prigerson

Harvard University

531 PUBLICATIONS 36,462 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Coping with Cancer R01s View project

Palliative care needs of terminally ill cancer patients View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Holly G Prigerson on 19 May 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

An Empirical Examination of the Stage Theory of Grief

Paul K. Maciejewski; Baohui Zhang; Susan D. Block; et al.

JAMA. 2007;297(7):716-723 (doi:10.1001/jama.297.7.716)

Online article and related content

current as of January 23, 2009. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/297/7/716

Supplementary material JAMA News Video

http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/297/7/716/DC1

Correction Correction is appended to this PDF and also available at

http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/jama;297/20/2200

Contact me if this article is corrected.

Citations This article has been cited 23 times.

Contact me when this article is cited.

Topic collections Psychosocial Issues; Psychiatry; Stress

Contact me when new articles are published in these topic areas.

Related Letters The Stage Theory of Grief

Roxane Cohen Silver et al. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2692.

Joseph S. Weiner. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2692.

George A. Bonanno et al. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2693.

In Reply:

Paul K. Maciejewski et al. JAMA. 2007;297(24):2693.

Subscribe Email Alerts

http://jama.com/subscribe http://jamaarchives.com/alerts

Permissions Reprints/E-prints

permissions@ama-assn.org reprints@ama-assn.org

http://pubs.ama-assn.org/misc/permissions.dtl

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on January 23, 2009

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

An Empirical Examination

of the Stage Theory of Grief

Paul K. Maciejewski, PhD

Context The stage theory of grief remains a widely accepted model of bereavement

Baohui Zhang, MS adjustment still taught in medical schools, espoused by physicians, and applied in di-

Susan D. Block, MD verse contexts. Nevertheless, the stage theory of grief has previously not been tested

empirically.

Holly G. Prigerson, PhD

Objective To examine the relative magnitudes and patterns of change over time post-

T

HE NOTION THAT A NATURAL PSY- loss of 5 grief indicators for consistency with the stage theory of grief.

chological response to loss Design, Setting, and Participants Longitudinal cohort study (Yale Bereavement

involves an orderly progres- Study) of 233 bereaved individuals living in Connecticut, with data collected between

sion through distinct stages of January 2000 and January 2003.

bereavement has been widely accepted Main Outcome Measures Five rater-administered items assessing disbelief, yearn-

by clinicians and the general public. ing, anger, depression, and acceptance of the death from 1 to 24 months postloss.

Bowlby and Parkes1-4 were the first to pro-

Results Counter to stage theory, disbelief was not the initial, dominant grief indi-

pose a stage theory of grief for adjust- cator. Acceptance was the most frequently endorsed item and yearning was the domi-

ment to bereavement that included 4 nant negative grief indicator from 1 to 24 months postloss. In models that take into

stages: shock-numbness, yearning- account the rise and fall of psychological responses, once rescaled, disbelief de-

searching, disorganization-despair, and creased from an initial high at 1 month postloss, yearning peaked at 4 months post-

reorganization. Kübler-Ross5 adapted loss, anger peaked at 5 months postloss, and depression peaked at 6 months postloss.

Bowlby and Parkes’ theory to describe a Acceptance increased throughout the study observation period. The 5 grief indicators

5-stage response of terminally ill patients achieved their respective maximum values in the sequence (disbelief, yearning, an-

to awareness of their impending death: ger, depression, and acceptance) predicted by the stage theory of grief.

denial-dissociation-isolation, anger, bar- Conclusions Identification of the normal stages of grief following a death from natu-

gaining, depression, and acceptance. The ral causes enhances understanding of how the average person cognitively and emo-

stage theory of grief became well- tionally processes the loss of a family member. Given that the negative grief indicators

known and accepted, and has been gen- all peak within approximately 6 months postloss, those who score high on these in-

dicators beyond 6 months postloss might benefit from further evaluation.

eralized to a wide variety of losses, includ-

JAMA. 2007;297:716-723 www.jama.com

ing children’s reactions to parental

separation,3 adults’ reactions to marital

separation,6 and clinical staffs’ reactions time.10-14 Bonanno et al10 found 5 diver- (yearning-anger-anxiety), depression-

to the death of an inpatient.7 A 1997 sur- gent grieving trajectories from preloss to mourning, and recovery. To date, no

vey conducted by Downe-Wamboldt and 18 months postloss (common grief, study has explicitly tested whether the

Tamlyn8 documented the heavy reli- chronic grief, chronic depression, im- normal course of adjustment to a natu-

ance of medical education on the Kübler- provement during bereavement, and re- ral death progresses through stages of

Ross model of grief. The National Can- silience). Wortman and Silver13 exam-

Author Affiliations: Department of Psychiatry, Wom-

cer Institute currently maintains a Web ined and disproved the necessity of 1 en’s Health Research, and Magnetic Resonance Re-

site on loss, grief, and bereavement that stage in the grief theory when they found search Center, Yale University School of Medicine, New

Haven, Conn (Dr Maciejewski); Center for Psycho-

describes the phases of grief. 9 As that depression was not an inevitable re- Oncology and Palliative Care Research, Dana-Farber

entrenched as the notion of phases of grief sponse to loss. Based on Bowbly and Cancer Institute, Boston, Mass (Ms Zhang and Drs

Block and Prigerson); and Department of Psychiatry,

may be, the hypothesized sequence of Parkes’1-4 and Kübler-Ross’5 theories, Ja- Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and Harvard Medi-

grief reactions has previously not been cobs14 synthesized and illustrated the hy- cal School Center for Palliative Care, Boston, Mass (Drs

Block and Prigerson).

investigated empirically. pothesized stage theory of grief, in which Corresponding Author: Holly G. Prigerson, PhD, Cen-

Several bereavement scholars have in- the normal response to loss progresses ter for Psycho-Oncology and Palliative Care Re-

search, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, 44 Binney St SW,

vestigated particular aspects of, or dia- through the following grief stages: G440A, Boston, MA 02115 (holly_prigerson@dfci

grammed changes in, grief reactions over numbness-disbelief, separation distress .harvard.edu).

716 JAMA, February 21, 2007—Vol 297, No. 7 (Reprinted) ©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on January 23, 2009

STAGE THEORY OF GRIEF

disbelief, yearning, anger, depression,

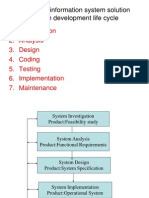

Figure 1. Hypothesized Stage Theory of Grief

and acceptance.

The identification of the patterns of

Disbelief Yearning Anger Depression

typical grief symptom trajectories is of Acceptance

clinical interest because it enhances the

understanding of how individuals cog-

nitively and emotionally process the

Indicator Rating

death of someone close. Such knowl-

edge aids in the determination of

whether a specific pattern of bereave-

ment adjustment is normal or not. Once

the normal patterns of grief are known,

individuals with abnormal bereave-

ment adjustment can be identified and

referred for treatment when indicated.

This study used data from a sample of

community-based bereaved individu- Time From Loss

als to examine the course of disbelief,

yearning, anger, depression, and accep-

tance as described by Jacobs14 from 1 to als, collected data between January 2000 ticipants from Bridgeport / Fairfield

24 months postloss. FIGURE 1 illus- and January 2003, and was funded by the (mean [SD], 63.2 [11.5] years) (P=.05).

trates the hypothesized sequence of National Institute of Mental Health. For The institutional review boards of all par-

stages of grief for this analysis. Be- greater Bridgeport/Fairfield, Conn, the ticipating sites approved the research

cause approximately 94% of US deaths names of the newly bereaved (ⱕ6 protocol.

result from natural causes (eg, vehicle months) were obtained from the divi- Individuals were invited to participate

crashes, suicide),15 deaths from unnatu- sion of the American Association of Re- in the study via a letter that described how

ral causes (eg, car crashes, suicide) were tired Persons Widowed Persons Ser- their names were obtained, identified the

excluded thereby enabling the results vice, a community-based outreach investigators, outlined the aims and pro-

to be generalized to the most common program. For the New Haven, Conn, cedures, and noted that they would be

types of deaths. Individuals who met the metropolitan and surrounding areas, contacted by study staff in the following

criteria for complicated grief disor- names were obtained from obituaries weekunlesstheyinformedusoftheirwish

der16,17 also were excluded so that the listed in the New Haven Register, through not to be contacted. Of the 575 persons

results would represent normal be- newspaper advertisements, fliers, per- contacted, 317 (55.1%) agreed to partici-

reavement reactions. Although the pro- sonal referrals, and referrals from the pate. Reasons for nonparticipation in-

posed stage theory of grief1-5,14 does not chaplain’s office of the St Raphael Hos- cludedreluctancetoparticipateinresearch

specify the precise timing of the stages, pital. A comparison between greater (n=11; 4.3%); being too busy (n=46;

Jacobs14 described the normal griev- Bridgeport/Fairfield Bureau of Vital Rec- 17.8%); being too upset (n=27; 10.5%);

ing process and each of its stages as ords death certificates and the Wid- “doing fine” (n=23; 8.9%); not being in-

being completed within 6 months fol- owed Persons Service list during the same terested or having no reason (n=145;

lowing the loss of a loved one. How- 3-month period revealed that the Wid- 56.2%); and having other reasons (n=6;

ever, in the absence of an established, owed Persons Service listings captured 2.3%). Compared with participants, non-

empirical foundation for the length of 95% of all deaths leaving behind a wid- participantsweresignificantlymorelikely

time associated with the normal griev- owed individual, suggesting that the list- to be male (25.9% vs 37.2%; P⬍.001) and

ing process, the normal grieving pro- ing provided an unbiased and compre- older (mean [SD] age, 61.7 [13.1] years

cess was not assumed to be limited to hensive ascertainment of recently vs 68.8 [13.7] years) (P⬍.001). Non–

6 months postloss in this study. In- widowed individuals in the sampled re- English-speaking persons and those con-

stead, the grief indicators were exam- gion. Participants recruited from greater sidered too frail to complete the interview

ined as functions of time up to 24 New Haven (37.0%) did not differ sig- wereineligible.The317participantswere

months postloss. nificantly from participants recruited interviewed at a mean (SD) of 6.3 (7.0)

from greater Bridgeport / Fairfield months after the death of a loved one. The

METHODS (63.0%) with respect to sex, income, edu- first follow-up interview (n=296; 93.4%)

Study Sample cation, race/ethnicity, or quality of life. wascompletedatamean(SD)of10.9(6.1)

The Yale Bereavement Study, a longitu- Participants recruited from greater New months postloss; second follow-up inter-

dinal examination of grief in a commu- Haven were significantly younger (mean view (n=263; 83.0%) at a mean (SD) of

nity-based sample of bereaved individu- [SD] age, 59.7 [16.4] years) than par- 19.7 (5.8) months postloss. Written in-

©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, February 21, 2007—Vol 297, No. 7 717

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on January 23, 2009

STAGE THEORY OF GRIEF

at baseline interview was 0.65 (P⬍.001).

Table 1. Demographic Variables of the Yale Bereavement Study Sample Compared With

2005 Data From the US Census To be consistent with the scale levels

Yale Bereavement of other grief indicators, all levels of

Study Sample 2005 US depressed mood were increased by 1 so

(N = 233), No. (%) Census, % that 1 indicated “absence of depressed

Age ⱖ65 y 125 (53.5) 76.1* mood” and 5 indicated “patient reports

Female sex 166 (71.2) 80.7*

virtually only these feeling states in his

White race 226 (97.0) 80.2*

spontaneous verbal and non-verbal

Education beyond high school 145 (62.2) 54.7†

communication.”

Median household income, $ 52 000 46 242‡

Individuals self-identified their racial/

*US widowed population (n = 13.7 million).

†US general population aged 25 years or older (n = 189.0 million). ethnic status according to the racial/

‡US general household population (N = 111.1 million households). ethnic categories defined in the US Cen-

sus.18 They also reported the cause of

formed consent was obtained from all in- Measures of Grief death for the family member or loved

dividuals enrolled in the study. The indicators of disbelief, yearning, one. For deaths due to a terminal ill-

Of the 317 individuals identified, anger, and acceptance of the death were ness, the date of the diagnosis was re-

58 were excluded because they met assessed using single items obtained corded. Diagnoses of the terminal ill-

criteria for complicated grief disor- from the rater-administered version of ness within 6 months (52/199; 26.1%)

der, 19 because they survived trau- the Inventory of Complicated Grief- were compared with those 6 months or

matic deaths, and 14 because they Revised, formerly known as the Trau- longer (147/199; 73.9%) prior to the

had missing data on examined mea- matic Grief Response to Loss. 1 9 death. Six months was used as the

sures. The study sample (N = 233) Although it would have been prefer- threshold because terminal diagnoses

consisted of individuals who did not able to use separate scales for the assess- of less than 6 months resulted in

meet criteria for complicated grief ment of yearning, disbelief, anger, and smaller, less reliable groupings and else-

disorder16,17 during the study; had a acceptance of the death, no such scales where16,17 it has been determined that

family member or loved one who exist for each of these grief stages. To 6 months is the time after which nor-

died from natural not traumatic maximize consistency across mea- mal grief can be distinguished from

causes; and had at least 1 complete sures, single items were used for all grief complicated grief disorder.

assessment of the 5 grief indicators phase indicators. Single-item inter-

included in the stage theory of grief view screenings have proven remark- Statistical Analyses

within 24 months postloss. The par- ably accurate in the prediction of depres- Statistical analyses were conducted to

ticipants were significantly older sion. 20 The frequency, rather than test for significant differences in the

(mean [SD] age, 62.9 [13.1] years; severity, of each grief indicator was used magnitude of each of the 5 grief indi-

53.5% aged ⱖ65 years) and more as the response format in the Inven- cators within each of the 3 postloss pe-

likely to be white (97.0%) than the tory of Complicated Grief-Revised riods (ⱕ6 months [1-6 months cat-

excluded individuals (mean [SD] because frequency has proven to be a egory], ⬎6 to ⱕ12 months [6-12

age, 58.5 [15.0] years; 90.4% white) more effective means of evaluating the months category], and ⬎12 to ⱕ24

but did not significantly differ with impact of events.21 Grief phase indica- months [12-24 months category]); to

respect to sex, income, education, tors were measured using a 5-point compare the pattern of changes in the

and relationship to the deceased. The Likert scale in which 1 equaled less than absolute levels of each of the 5 grief in-

vast majority of participants were once per month; 2, monthly; 3, weekly; dicators over time; and to determine

spouses of the deceased (83.8%). The 4, daily; and 5, several times per day. when each of the 5 grief indicators

remaining participants (16.2%) were These items showed moderately high achieved its maximum value.

adult children, parents, or siblings of correlations with the total Inventory of Specifically, single-sample t tests and

the deceased. Complicated Grief-Revised score at nonlinear, ordinary least squares re-

The data from the participants were baseline interview, which ranged in gression analyses were used to exam-

compared with data from the 2005 US magnitude from 0.47 to 0.57 (all com- ine the differences in magnitude be-

Census (TABLE 1).18 Compared with the parisons yielded P⬍.001). To enhance tween grief indicators at a given time

US widowed population, the study par- comparability in the measurement of postloss and changes in grief indica-

ticipants were younger, more likely to be each indicator, depression was assessed tors as a function of time postloss.

male,andahigherproportionwerewhite. using the single-item depressed mood Single-sample t tests were used to ex-

Compared with the US general popula- in the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depres- amine within-person differences in

tion aged 25 years or older, the study par- sion. 2 2 The correlation between magnitude between the 5 grief indica-

ticipants were better educated and had a depressed mood and the total Hamil- tors postloss at 1 to 6 months, 6 to 12

higher median household income. ton Rating Scale for Depression score months, and 12 to 24 months and

718 JAMA, February 21, 2007—Vol 297, No. 7 (Reprinted) ©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on January 23, 2009

STAGE THEORY OF GRIEF

Table 2. Grief Indicators Assessed During 3 Postloss Periods

Period of Postloss Assessment, mo

1-6 6-12 12-24

Grief No. of Mean No. of Mean No. of Mean

Indicator* Participants (SD) Participants (SD) Participants (SD)

Disbelief 173 2.27 (1.30) 211 1.80 (1.03) 205 1.61 (0.94)

Yearning 171 3.77 (1.14) 212 3.18 (1.19) 205 2.64 (1.20)

Anger 174 1.87 (1.16) 210 1.80 (1.04) 205 1.55 (0.87)

Depression 174 2.29 (1.25) 213 2.29 (1.21) 205 1.80 (1.07)

Acceptance 143 4.11 (1.21) 209 4.49 (0.93) 205 4.70 (0.68)

*Indicators are measured on a scale of 1 to 5.

within-person temporal changes in Institute Inc, Cary, NC). P ⬍ .05 was postloss: t204 =35.24, P⬍.001), and de-

magnitude of each grief indicator post- considered significant. pression (1-6 months postloss:

loss between 1 to 6 months and 6 to 12 A series of multivariable analyses of t142 =11.64, P⬍.001; 6-12 months post-

months and between 6 to 12 months variance were conducted to evaluate loss: t208 =18.84, P⬍.001; 12-24 months

and 12 to 24 months. whether demographic variables and re- postloss: t204 =29.97, P⬍.001).

Nonlinear, ordinary least squares re- port of diagnosis of terminal illness Yearning is significantly greater than

gression analyses were used to model within 6 months of the death were sig- disbelief (1-6 months postloss:

the trajectory of each grief indicator as nificantly related to the 5 grief indica- t169 =13.57, P⬍.001; 6-12 months post-

a function of time postloss. Because the tors or to the within-person differ- loss: t210 =15.57, P⬍.001; 12-24 months

stage theory of grief predicts the se- ences between or temporal changes in postloss: t204 = 12.49, P⬍.001), anger

quential rise and fall of each of the grief the 5 grief indictors. (1-6 months postloss: t 170 = 16.43,

indicators as a function of time post- P⬍.001; 6-12 months postloss:

loss (ie, phase), we chose the follow- RESULTS t209 =15.10, P⬍.001; 12-24 months post-

ing parametric functional form that The means and SDs for the 5 grief in- loss: t204 =12.43, P⬍.001), and depres-

would capture such phases: dicators of disbelief, yearning, anger, de- sion (1-6 months postloss: t170 =14.40,

pression, and acceptance postloss at 1 P⬍.001; 6-12 months postloss:

Y =[A ⫹ B (−t/τ ⫹ 1)] exp(−1⁄2 t/τ) ⫹ C

to 6 months, 6 to 12 months, and 12 t211 =9.75, P⬍.001; 12-24 months post-

where Y represents the value of the grief to 24 months appear in TABLE 2. Within loss: t204 =9.41, P⬍.001).

indicator and the term t/τ represents each period, acceptance is greater than Depression is significantly greater

time postloss with t scaled by the model disbelief, yearning, anger, and depres- than anger (1-6 months postloss:

parameter τ. The expression [A ⫹ B sion; yearning is greater than disbe- t173 =3.61, P⬍.001; 6-12 months post-

(−t/τ ⫹ 1)] exp(−1⁄2 t/τ) represents a lin- lief, anger, and depression; and depres- loss: t209 =5.32, P⬍.001; 12-24 months

ear combination of normalized sion is greater than anger. Between 1 postloss: t204 =3.16, P=.002).

(weighted) zero-order and first-order and 6 months postloss and 6 and 12 Disbelief is significantly greater than

Laguarre polynomials, scaled by the months postloss, disbelief and yearn- anger at 1 to 6 months postloss

model parameters A and B, respec- ing decline and acceptance increases. (t172 =3.22, P=.002); depression is sig-

tively, included to capture the antici- From 6 to 12 months postloss and 12 nificantly greater than disbelief at 6 to

pated rise and fall in the data. Model to 24 months postloss, disbelief, yearn- 12 months postloss (t210 =5.22, P⬍.001)

parameter C represents the asymp- ing, anger, and depression decline and and at 12 to 24 months postloss

totic value that the grief indicator ap- acceptance increases. (t204 =2.19, P=.03).

proaches as time postloss increases to More specifically, acceptance is sig- Between 1 and 6 months postloss and

infinity. One observation per person nificantly greater than disbelief (1-6 6 and 12 months postloss, disbelief

(N = 233), selected randomly among months postloss: t142 =10.79, P⬍.001; (t 157 = 4.78, P⬍.001) and yearning

those observations that contained com- 6-12 months postloss: t 208 = 23.16, (t156 =7.89, P⬍.001) decline and accep-

plete data for each of the 5 grief indi- P⬍.001; 12-24 months postloss: tance increases (t130 =3.91, P⬍.001). Be-

cators within 24 months postloss, was t204 = 31.88, P⬍.001), yearning (1-6 tween 6 and 12 months postloss and 12

used to fit these regression models. For months postloss: t142 =2.11, P=.04; 6-12 and 24 months postloss, disbelief

each grief indicator, the model para- months postloss: t208 =10.80, P⬍.001; (t190 =2.84, P=.005), yearning (t191 =5.96,

meters τ, A, B, and C were estimated by 12-24 months postloss: t204 = 19.39, P⬍.001), anger (t189 = 3.91, P⬍.001),

means of nonlinear, ordinary least P⬍.001), anger (1-6 months postloss: and depression (t192 = 5.60, P⬍.001)

squares regression implemented using t142 =12.66, P⬍.001; 6-12 months post- decline and acceptance increases

PROC MODEL in SAS version 9.1 (SAS loss: t208 =23.14, P⬍.001; 12-24 months (t188 =3.37, P⬍.001).

©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, February 21, 2007—Vol 297, No. 7 719

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on January 23, 2009

STAGE THEORY OF GRIEF

FIGURE 2 displays the results of the tween 1 and 4 months postloss, de- than depression between 1 and 4

nonlinear regression analyses. Accord- creases between 4 and 24 months post- months postloss. Depression in-

ing to the models displayed in the top loss, and is greater than disbelief, anger, creases between 1 and 6 months post-

part of Figure 2, acceptance increases and depression between 1 and 24 loss, decreases between 6 and 24

monotonically (uniformly in 1 direc- months postloss. Disbelief decreases months, is greater than disbelief post-

tion), and is greater than each of the monotonically between 1 and 24 loss between 4 and 24 months, and is

other grief indicators between 1 and 24 months, is greater than anger between greater than anger between 1 and 24

months postloss. Yearning increases be- 1 and 6 months postloss, and is greater months postloss. Anger increases be-

tween 1 and 5 months postloss and de-

Figure 2. Empirical and Rescaled Models for Grief Indicators as Functions of Time

creases between 5 and 24 months post-

loss. The close agreement between the

Grief Indicators models and the data in the top part of

5.0 Figure 2 indicates that the phasic func-

Acceptance

tional form specified in the regression

models adequately represent the data.

4.0 The bottom part of Figure 2 dis-

plays the regression models following a

Indicator Rating

rescaling procedure that constrains each

3.0 grief indicator to fall within the inter-

Yearning val of 0 through 1. In the top part of

Figure 2, the relative locations in time

2.0 of the peaks of the grief indicators are

Depression

obscured because the curves are not side

Anger

Disbelief

by side, thereby making comparisons

1.0

0 6 12 18 24

difficult. Those comparisons are facili-

Time From Loss, mo tated in the bottom part of Figure 2 by

placing all of the indicators on the same

Rescaled Grief Indicators scale. The 5 grief indicators achieved

Disbelief Yearning Anger Depression Acceptance their respective maximum values in the

Maximum

1.0

Value sequence (disbelief, yearning, anger, de-

pression, and acceptance) predicted by

0.8 the stage theory of grief. Given that there

Rescaled Indicator Rating

are 120 possible sequences of these 5 in-

dicators, the probability that the ob-

0.6

served sequence is exactly the se-

quence predicted by the stage theory of

0.4 grief by chance alone is P=.008.

Based on the results of the multivari-

0.2

able analyses of variance, the demo-

graphic factors of age, sex, race/

Minimum

ethnicity (white/nonwhite), education,

0

Value 0 6 12 18 24 and income and a terminal illness diag-

Time From Loss, mo nosis reported within 6 months of the

death were largely unrelated to within-

Top, The curves represent grief indicators as functions of time based on nonlinear regression models estimated person differences and temporal changes

from the data (N = 233). The data markers along the x-axis are determined by the mean value of time from

loss for the individuals included in the 10 groups of observations (n = 23 observations per group for 9 groups; in the grief indictors throughout the

n = 26 observations for 1 group). The corresponding error bars indicate SDs. These 10 groups of observations study observation period (1-6, 6-12, and

were formed by ordering all of the observations used in the regression analyses (N = 233) by increasing time

postloss (observations that occurred at the same time postloss were randomly assigned a position in the or- 12-24 months postloss). Education be-

dered sequence of observations for that time), and then assigning the first 23 observations on this ordered list yond high school was significantly as-

to the first group, the next 23 observations to the second group, etc. The regression curves are based on the

analysis of individual data points (N = 233) for which time from loss varies from 1.5 to 23 months. Bottom, The

sociated with grief indicators 12 to 24

curves represent grief indicators as functions of time based on nonlinear regression models after the following months postloss (Wilks = 0.94,

rescaling procedure: (t)=[Y(t) − Ymin]/Ymax − Ymin], where Y(t) is the model value for the grief indicator at time F5,199 =2.52; P=.03), due to its signifi-

t, and Ymin and Ymax are the minimum and maximum model values of the grief indicator, respectively, between

1 and 24 months postloss. The 5 grief indicators achieve their respective maximum values in the exact se- cant associations with lesser disbelief

quence (disbelief, yearning, anger, depression, and acceptance) predicted by the hypothesized theory of grief (P=.05) and depression (P=.003), and

presented in Figure 1.

with greater acceptance (P=.02) dur-

720 JAMA, February 21, 2007—Vol 297, No. 7 (Reprinted) ©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on January 23, 2009

STAGE THEORY OF GRIEF

ing that period. Education beyond high als who survived a family member’s trau- cal Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth

school was also significantly associated matic death and those who met criteria Edition with respect to bereavement.

with within-person differences in grief for complicated grief disorder,16 both Models that tested for phasic epi-

indicators 6 to 12 months postloss groups of whom were found in prelimi- sodes of each grief indicator revealed that

(Wilks =0.95, F4,204 =2.51; P=.04) and nary analyses to have significantly lower disbelief about the death is highest ini-

12 to 24 months postloss (Wilks =0.94, levels of acceptance relative to the study tially. As disbelief declined from the first

F4,200 = 3.11; P = .02) due to its signifi- sample. The lower frequency of accep- month postloss, yearning rose until 4

cant associations with greater differ- tance of the death among participants months postloss and then declined. An-

ences between acceptance and each of who reported that the patient’s termi- ger over the death was fully expressed

the other grief indicators during each of nal illness diagnosis was within 6 months at 5 months postloss. After anger de-

those periods. Widowhood (compared compared with 6 months or longer prior clines, severity of depressive mood peaks

with loss of a parent, child, or sibling in to the death suggests that prognostic at approximately 6 months postloss and

this study group) was significantly as- awareness may promote acceptance of thereafter diminishes in intensity

sociated with within-person differ- the death. This result is consistent with through 24 months postloss. Accep-

ences in grief indicators 1 to 6 months findings reported elsewhere indicating tance increased steadily through the

postloss (Wilks = 0.93, F4,135 = 2.51; that preparation for the death is associ- study observation period ending at 24

P=.05), due to its significant associa- ated with better psychological adjust- months postloss. Because of the minus-

tions with a greater difference between ment to the loss.23 Future research that cule probability that by chance alone

yearning and depression (P=.02) and a examines the effects of prospective rather these 5 grief indicators would achieve

lesser difference between acceptance and than retrospective reports of prognostic their respective maximum values in the

yearning (P=.01) during that period. Re- awareness on the bereaved survivor’s ac- precise hypothesized sequence,14 these

port of a terminal illness diagnosis within ceptance are needed before definitive results provide at least partial support

6 months of the death was significantly conclusions can be drawn. for the stage theory of grief.

associated with grief indicators 12 to 24 Yearning was the most frequent nega- The results also offer a point of ref-

months postloss (Wilks = 0.93, tive psychological response reported erence for distinguishing between nor-

F5,172 =2.62; P=.03), due to its signifi- throughout the study observation pe- mal and abnormal reactions to loss.

cant association with lower acceptance riod (1-6, 6-12, and 12-24 months post- Given that the negative grief indica-

of the death (P = .008) during that loss). Yearning was significantly more tors all peak within 6 months, those in-

period. common than depressed mood despite dividuals who experience any of the in-

the exclusive focus in the Diagnostic and dicators beyond 6 months postloss

COMMENT Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, would appear to deviate from the nor-

Results of this study identify normal Fourth Edition24 bereavement section on mal response to loss. These findings also

patterns of grief processing over time depressive symptomatology: “As part of support the duration criterion of 6

following the natural death of a loved their reaction to the loss, some griev- months postloss for diagnosing com-

one. Given that the vast majority ing individuals present with symptoms plicated grief disorder,16,17,19,25 or what

(94%) of deaths in the United States characteristic of a Major Depressive Epi- is now referred to as prolonged grief dis-

are the result of natural causes,15 the sode (e.g., feelings of sadness . . . The be- order.26 Unlike the term complicated,

findings reflect how the average per- reaved individual typically regards the which is defined as “difficult to ana-

son psychologically processes a typical depressed mood as ‘normal,’ . . . The di- lyze, understand, explain,” 27 pro-

death of a close family member. agnosis of Major Depressive Disorder is longed grief disorder accurately de-

Although the temporal course of the generally not given unless the symp- scribes a bereavement-specific mental

absolute levels of the 5 grief indicators toms are still present 2 months after the disorder based on symptoms of grief

did not follow that proposed by the loss.”24(p684) Findings from this report that persist longer than is normally the

stage theory of grief,14 when rescaled demonstrate that yearning, not depres- case (ie, ⬎6 months postloss based on

and examined for each indicator’s sive mood, is the salient psychological the results of the present study). Fur-

peak, the data fit the hypothesized response to natural death. They indi- thermore, prolonged grief disorder per-

sequence exactly. cate that depressive mood in normally mits the recognition of other psychiat-

In terms of absolute frequency, and bereaved individuals tends to peak at ap- ric complications of bereavement, such

counter to the stage theory, disbelief was proximately 6 months postloss and does as major depressive disorder and post-

not the initial, dominant grief indica- not occur prior to 2 months postloss. traumatic stress disorder. Additional

tor. Acceptance was the most often en- Findings elsewhere25,26 indicate that analyses are needed to examine grief tra-

dorsed item. Evidently, a high degree of chronically elevated levels of yearning jectories among those meeting criteria

acceptance, even in the initial month are a cause for clinical concern. Taken for prolonged grief disorder.

postloss, is the norm in the case of natu- together, these results imply a need for The mode of death may be an im-

ral deaths. This contrasts with individu- revision of the Diagnostic and Statisti- portant factor that influences the course

©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, February 21, 2007—Vol 297, No. 7 721

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on January 23, 2009

STAGE THEORY OF GRIEF

of bereavement adjustment. In the pre- markably similar patterns to those pre- months is therefore likely to reflect a

sent study, individuals bereaved by sented herein. We chose to present the more difficult than average adjust-

traumatic deaths (eg, vehicle crashes, items that fit most closely with the stage ment and suggests the need for fur-

suicide) were removed. Bereavement indicators illustrated in the literature.14 ther evaluation of the bereaved survi-

adjustment following deaths from trau- It should be noted that participants vor and potential referral for treatment.

matic causes may be more difficult to were younger and less likely to be male The results provide an evidence base

process and demonstrate higher de- compared with the study nonpartici- from which to educate clinicians (eg,

grees of disbelief and anger and lower pants, and that the study sample may primary and palliative care physi-

levels of acceptance than those re- be more resilient than is typically the cians, geriatricians, psychiatrists, on-

ported herein. A recent study found that case given the low prevalence of de- cologists, related hospital and hospice

those bereaved by traumatic vs natu- pression (8.9% of the individuals had staff, bereavement counselors) and lay-

ral deaths had greater difficulty in mak- a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depres- persons (eg, patients, family mem-

ing sense of the loss.28 Participants who sion summary score of ⱖ17) com- bers, friends) about what to expect fol-

reported that the family member or pared with other samples of bereaved lowing the death of a family member

loved one’s terminal illness was diag- individuals.29-31 Samples with more or loved one.

nosed within 6 months of the death did males or with older and more dis- Author Contributions: Drs Maciejewski and Prigerson

not differ significantly from other par- tressed individuals might reveal a dif- had full access to all of the data in the study and take

ticipants with respect to their level of ferent pattern of grief trajectories than responsibility for the integrity of the data and the ac-

curacy of the data analysis.

grief indicators. However, the partici- those presented herein. Although the Study concept and design: Maciejewski, Prigerson.

pants who reported the diagnosis within study sample does show some gross Acquisition of data: Prigerson.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Maciejewski,

6 months of the death did report ac- similarities with the US widowed popu- Zhang, Block, Prigerson.

ceptance of the death significantly less lation in terms of age, sex, and race / Drafting of the manuscript: Maciejewski, Zhang,

Prigerson.

often. Subanalyses revealed that disbe- ethnicity, and with other comparable Critical revision of the manuscript for important intel-

lief within 6 months postloss was also groups in terms of education and me- lectual content: Maciejewski, Zhang, Block, Prigerson.

Statistical analysis: Maciejewski, Zhang.

significantly higher in those for whom dian household income, it is not di- Obtained funding: Maciejewski, Prigerson.

the patient’s terminal illness diagnosis rectly representative of either the US Administrative, technical, or material support: Zhang,

was reported to be within 6 months widowed or US general population. Prigerson.

Study supervision: Maciejewski, Block, Prigerson.

prior to death. Thus, the manner and Nevertheless, age, income, race / Financial Disclosures: None reported.

forewarning of the death appear to affect ethnicity, and sex were not signifi- Funding/Support: This work was supported by grants

MH56529 (awarded to Dr Prigerson) and MH63892

the processing of grief. Studies are cantly associated with the magnitude (awarded to Dr Prigerson) from the National Institute of

needed to explore the pattern of grief or course of grief and the representa- Mental Health and grant CA106370 (awarded to Dr

Prigerson) from the National Cancer Institute; and grant

trajectories among the survivors be- tiveness of the Yale Bereavement Study NS044316 (awarded to Dr Maciejewski) from the Na-

reaved by traumatic causes of death. would not appear to restrict the gen- tionalInstituteofNeurologicalDisordersandStroke.Fund-

The results should be understood in eralizability of the results to the US wid- ing also was provided by the Center for Psycho-Oncology

and Palliative Care Research, Dana-Farber Cancer Insti-

light of several study limitations. Ide- owed population. Despite these limi- tute, and Women’s Health Research at Yale University.

ally, all individuals would have been as- tations, given that the Yale Bereavement Role of the Sponsors: The National Institute of Men-

tal Health, National Cancer Institute, National Insti-

sessed immediately after the loss rather Study provides one of the most com- tute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Center for

than beginning at month 1 postloss. Due prehensive longitudinal assessments of Psycho-Oncology and Palliative Care Research, Dana-

Farber Cancer Institute, and Women’s Health Re-

to respect for the initial mourning pe- grief, these data are as adequate as any search at Yale University had no direct input into the

riod and institutional review board con- available for testing the stages of grief design or conduct of the study; collection, manage-

ment, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or prepa-

cerns about harm to participants, we did over time. ration, review, or approval of the manuscript.

not interview individuals within a month In conclusion, the results of this

of the death. In addition, it would have study provide what appears to be the REFERENCES

been better to analyze data that reas- first empirical examination of the stage

1. Bowlby J. Processes of mourning. Int J Psychoanal.

sessed individuals each month from 0 theory of grief. They indicate that in the 1961;42:317-339.

to 24 months postloss. However, no such circumstance of natural death, the nor- 2. Parkes C. Bereavement: Studies in Grief in Adult

Life. London, England: Tavistock; 1972.

data exist nor does the stage theory1-5 mal response involves primarily accep- 3. Bowlby J. Attachment and Loss. New York, NY: Ba-

specify in what month postloss each tance and yearning for the deceased. sic Books; 1980.

stage would predominate. And, al- Each grief indicator appears to peak in 4. Parkes CM, Weiss RS. Recovery From Bereavement.

New York, NY: Basic Books; 1983.

though we acknowledge that other grief the sequence proposed by the stage 5. Kübler-Ross E. On Death and Dying. New York,

indicators might have been used, the theory. Regardless of how the data are NY: Macmillan; 1969.

6. Gray C, Koopman E, Hunt J. The emotional phases

various proxy measures (eg, stunned for analyzed, all of the negative grief indi- of marital separation: an empirical investigation. Am

disbelief, bitterness for anger, hopeless- cators are in decline by approximately J Orthopsychiatry. 1991;61:138-143.

7. Leibenluft E, Green SA, Giese AA. Mourning and

ness for depression, quality of life scores 6 months postloss. The persistence of milieu: staff reaction to the death of an inpatient. Psy-

for acceptance/recovery) all revealed re- these negative emotions beyond 6 chiatr Hosp. 1988;19:169-173.

722 JAMA, February 21, 2007—Vol 297, No. 7 (Reprinted) ©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on January 23, 2009

STAGE THEORY OF GRIEF

8. Downe-Wamboldt B, Tamlyn D. An international 17. Zhang B, El-Jawahri A, Prigerson HG. Update on In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Dis-

survey of death education trends in faculties of nurs- bereavement research: evidence-based guidelines orders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psy-

ing and medicine. Death Stud. 1997;21:177-188. for the diagnosis and treatment of complicated chiatric Association; 1994:684.

9. National Cancer Institute. Cancer topics: loss, grief bereavement. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1188-1203. 25. Prigerson HG, Jacobs SC. Caring for bereaved pa-

and bereavement. http://www.nci.nih.gov 18. US Census Bureau. Population, housing, eco- tients: “all the doctors just suddenly go.” JAMA. 2001;

/cancertopics/pdq/supportivecare/bereavement nomic, and geographic data. http://factfinder.census 286:1369-1376.

/Patient/page6. Accessed November 28, 2006. .gov/servlet/NPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US& 26. Prigerson HG, Vanderwerker LC, Maciejewski PK.

10. Bonanno GA, Wortman CB, Lehman DR, et al. -qr_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_NP01&-ds_name= Prolonged grief disorder as a mental disorder: inclu-

Resilience to loss and chronic grief: a prospective study &-redoLog=false. Accessed November 28, 2006. sion in DSM. In: Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, Stroebe

from preloss to 18-months postloss. J Pers Soc Psychol. 19. Prigerson HG, Jacobs SC. Traumatic grief as a dis- W, Schut HA, eds. Handbook of Bereavement Re-

2002;83:1150-1164. tinct disorder: a rationale, consensus criteria, and a pre- search and Practice: 21st Century Perspectives. Wash-

11. Middleton W, Raphael B, Burnett P, Martinek N. liminary empirical test. In: Stroebe MS, Hansson RO, ington, DC: American Psychological Association Press;

A longitudinal study comparing bereavement phe- Stroebe W, Schut H, eds. Handbook of Bereavement 2007.

nomena in recently bereaved spouses, adult children Research: Consequences, Coping, and Care. Wash- 27. Dictionary.com Web site. Definitions for the word

and parents. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1998;32:235- ington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001: complicated. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse

241. 588-613. /complicated. Accessibility verified January 18,

12. Ott CH, Lueger RJ. Patterns of change in mental 20. Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M. “Are you 2007.

health status during the first two years of spousal depressed?” screening for depression in the termi- 28. Currier JM, Holland JM, Neimeyer RA. Sense-

bereavement. Death Stud. 2002;26:387-411. nally ill. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:674-676. making, grief, and the experience of violent loss: to-

13. Wortman CB, Silver RC. The myths of coping with 21. Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event ward a mediational model. Death Stud. 2006;30:403-

loss. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57:349-357. scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 428.

14. Jacobs S. Pathologic Grief: Maladaptation to Loss. 1979;41:209-218. 29. Clayton PJ, Halikas JA, Maurice WL. The depres-

Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1993. 22. Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neu- sion of widowhood. Br J Psychiatry. 1972;120:71-77.

15. Hoyert DL, Kung HC, Smith BL. Deaths: preliminary rol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62. 30. Zisook S, Shuchter SR. Depression through the first

data for 2003. Vital Health Stat 15. 2005;(53):16-18. 23. Barry LC, Kasl SV, Prigerson HG. Psychiatric dis- year after the death of a spouse. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;

16. Prigerson HG, Maciejewski PK. A call for sound orders among bereaved persons: the role of per- 148:1346-1352.

empirical testing and evaluation of criteria for com- ceived circumstances of death and preparedness for 31. Zisook S, Shuchter SR, Sledge PA, et al. The spec-

plicated grief proposed for DSM-V. Omega J Death death. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:447-457. trum of depressive phenomena after spousal

Dying. 2005;52:9. 24. American Psychiatric Association. Bereavement. bereavement. J Clin Psychiatry. 1994;55(suppl):29-36.

I find that a great part of the information I have was

acquired by looking up something and finding some-

thing else along the way.

—Franklin P. Adams (1881-1960)

©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, February 21, 2007—Vol 297, No. 7 723

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on January 23, 2009

LETTERS

Drafting of the manuscript: Croft, Darbyshire, van Thiel. 4. Ciminera P, Brundage J. Malaria in US military forces: a description of deploy-

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Croft, Dar- ment exposures from 2003 through 2005. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:275-279.

byshire, Jackson, van Thiel. 5. Croft AM. Malaria: prevention in travelers. In: Tovey D, ed. Clinical Evidence.

Financial Disclosures: None reported. London, England: BMJ Publishing Group; 2005:954-972.

Funding/Support: No outside funding or support was received for this study. 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The yellow book, travelers’ health,

Disclaimer: The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this study are those regional malaria information. http://www.cdc.gov/travel/regionalmalaria/indianrg

of the authors and should not be construed as the official North Atlantic Treaty .htm#malariarisk. Accessed February 26, 2007.

Organization or non-North Atlantic Treaty Organization military position, policy, 7. Lawrance CE, Croft AM. Do mosquito coils prevent malaria? a systematic re-

or decision, unless so designated by other official documentation. view of trials. J Travel Med. 2004;11:92-96.

Acknowledgment: We thank Ratimir Benčić, MD (ISAF Croatia), Roman Jantoš,

MD (ISAF Slovakia), Serdor Kavak, MD (ISAF Turkey), Lopez Poves, MD (ISAF

Spain), and Carl Gustav Schultz, MD (ISAF Sweden), for their help in facilitating

this survey. They received no compensation for participation in this study.

CORRECTION

1. Funk-Baumann M. Geographic distribution of malaria at traveler destinations.

In: Schlagenhauf P, ed. Travelers’ Malaria. Hamilton, Ontario: BC Decker, Inc; 2001: Incorrect Example: In the Original Contribution entitled “An Empirical Examina-

56-93. tion of the Stage Theory of Grief” published in the February 21, 2007, issue of

2. Malaria in military personnel returning from Afghanistan. Commun Dis Rep CDR JAMA (2007;297:716-723), an incorrect example was provided for natural causes.

Wkly. 2002;12:4-5. http://www.hpa.org.uk/cdr/archives/2002/cdr2702.pdf. Ac- On page 717, column 1, second full paragraph, the third sentence should be “Be-

cessed February 26, 2007. cause approximately 94% of US deaths result from natural causes (eg, heart dis-

3. Boecken GH. Pathogenesis and management of a late manifestation of vivax ease, cancer),15 deaths from unnatural causes (eg, car crashes, suicide) were ex-

malaria after deployment to Afghanistan: conclusions for NATO armed forces medi- cluded thereby enabling the results to be generalized to the most common types

cal services. Mil Med. 2005;170:488-491. of death.”

Medicine requires not only the intellectual cultiva-

tion of a science, but the patience and the practical

skill of an art. At the bedside we must be animated

by the feeling of faithful artisans, of men whose ob-

ject and duty is practical work; for when the art of

medicine is needed by the suffering and the dying it

is no question of mere theoretical knowledge and ex-

traneous acquirement. But skill in the commonest art

it is not to be attained without much practice, far less

in the complicated and difficult art of healing, where

every case presents some peculiarities. To practice it

successfully, we must have made our home at the bed-

side, and, if I may say so, have lived with disease, ob-

serving it in all its forms and changes.

—Sir William Withey Gull (1816-1890)

2200 JAMA, May 23/30, 2007—Vol 297, No. 20 (Reprinted) ©2007 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded from www.jama.com by guest on January 23, 2009

View publication stats

You might also like

- Advances in Experimental Clinical Psychology: Pergamon General Psychology SeriesFrom EverandAdvances in Experimental Clinical Psychology: Pergamon General Psychology SeriesNo ratings yet

- A Scale To Assess Attitudes Toward Euthanasia: OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying February 2005Document11 pagesA Scale To Assess Attitudes Toward Euthanasia: OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying February 2005diradosta_1992No ratings yet

- Essay 3 1Document5 pagesEssay 3 1api-705135923No ratings yet

- Medicine American Journal of Hospice and PalliativeDocument7 pagesMedicine American Journal of Hospice and PalliativeFlory23ibc23No ratings yet

- RoughbiblioxxxDocument9 pagesRoughbiblioxxxapi-321363387No ratings yet

- Gender Differences in Bipolar Disorder RDocument6 pagesGender Differences in Bipolar Disorder RCharpapathNo ratings yet

- FinalbiblioxxxDocument9 pagesFinalbiblioxxxapi-321363387No ratings yet

- Christopher Boorse (Auth.), James M. Humber, Robert F. Almeder ( - What Is Disease - (1997, Humana) (10.1007 - 978!1!59259-451-1) - Libgen - LiDocument358 pagesChristopher Boorse (Auth.), James M. Humber, Robert F. Almeder ( - What Is Disease - (1997, Humana) (10.1007 - 978!1!59259-451-1) - Libgen - LiLeon TrellesNo ratings yet

- What Happens After Treatment? A Systematic Review of Relapse, Remission, and Recovery in Anorexia NervosaDocument12 pagesWhat Happens After Treatment? A Systematic Review of Relapse, Remission, and Recovery in Anorexia NervosaRoberto Alexis Molina CampuzanoNo ratings yet

- The Haunted Self Structural Dissociation and The T PDFDocument7 pagesThe Haunted Self Structural Dissociation and The T PDFKomáromi PéterNo ratings yet

- NIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptDocument12 pagesNIH Public Access: Author ManuscriptgremnisayNo ratings yet

- Short-Term Group Therapies For Complicated Grief: Two Research-Based ModelsDocument11 pagesShort-Term Group Therapies For Complicated Grief: Two Research-Based Modelsrobertd33No ratings yet

- Patofisiologi CRFDocument11 pagesPatofisiologi CRFBagas PatihNo ratings yet

- Measures of Psychological Stress and Physical Health in Family Caregivers of Stroke Survivors A Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesMeasures of Psychological Stress and Physical Health in Family Caregivers of Stroke Survivors A Literature ReviewaNo ratings yet

- Music Interventions To Reduce Stress and Anxiety in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument9 pagesMusic Interventions To Reduce Stress and Anxiety in Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisMahco YegemeikupaNo ratings yet

- Depressive Personality Disorder Theoretical Issues, Clinical Findings, and Future Research QuestionsDocument12 pagesDepressive Personality Disorder Theoretical Issues, Clinical Findings, and Future Research QuestionsJhoelis SalazarNo ratings yet

- Disrupted Self-Perception in People With Chronic LDocument12 pagesDisrupted Self-Perception in People With Chronic L杨钦杰No ratings yet

- 2007 - Metacognitive Training For Schizophrenia Patients (MCT) A Pilot Study On Feasibility, Treatment Adherence, and Subjective EffDocument10 pages2007 - Metacognitive Training For Schizophrenia Patients (MCT) A Pilot Study On Feasibility, Treatment Adherence, and Subjective EffBartolomé Pérez GálvezNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography On The Concept of GriefDocument4 pagesAnnotated Bibliography On The Concept of GriefKeyvoh KeymanNo ratings yet

- Freemanetal 2014 JCCAPreviewpubmedDocument32 pagesFreemanetal 2014 JCCAPreviewpubmedRayén F. HuenchunaoNo ratings yet

- Writing As Therapy: BMJ Clinical Research July 1999Document4 pagesWriting As Therapy: BMJ Clinical Research July 1999JalusaMichelNo ratings yet

- Powell, Religion, Spirituality, Health, AmPsy, 2003Document17 pagesPowell, Religion, Spirituality, Health, AmPsy, 2003Muresanu Teodora IlincaNo ratings yet

- Pontes de AfetoDocument18 pagesPontes de AfetoSociedade InterAmericana de HipnoseNo ratings yet

- Grief Following Miscarriage A Comprehensive Review of The LiteratureDocument14 pagesGrief Following Miscarriage A Comprehensive Review of The LiteratureAdiwisnuuNo ratings yet

- Beyond BeliefDocument18 pagesBeyond BeliefSunMoon100% (2)

- PDSS PDFDocument6 pagesPDSS PDFItahisa JimenezNo ratings yet

- Review of Bowen Theory S SecretsDocument6 pagesReview of Bowen Theory S SecretsEDNA LILIANA BURBANO CALVACHENo ratings yet

- Family GriefDocument54 pagesFamily Griefadriiiana07No ratings yet

- Upload 5Document9 pagesUpload 5umair muqriNo ratings yet

- 2008 Article 32121Document6 pages2008 Article 32121elmarvin22No ratings yet

- The Case of Jane - A Pinean ApproachDocument20 pagesThe Case of Jane - A Pinean ApproachSoraya RamosNo ratings yet

- Bereaved Persons Are Misguided Through The Stages of Grief (Done)Document19 pagesBereaved Persons Are Misguided Through The Stages of Grief (Done)Plugaru CarolinaNo ratings yet

- Shabad Beliefsabout Causesof Depression TDSJCL2011Document12 pagesShabad Beliefsabout Causesof Depression TDSJCL2011zulfikarfuadiNo ratings yet

- Longevity, Regeneration, and Optimal Health (5-19) - Toward A Unified Field of StudyDocument15 pagesLongevity, Regeneration, and Optimal Health (5-19) - Toward A Unified Field of StudyCraig Van HeerdenNo ratings yet

- Articol 1 ADocument12 pagesArticol 1 AClara Iulia BoncuNo ratings yet

- Kaplow 2012Document23 pagesKaplow 2012Valentina RojasNo ratings yet

- 2014 - Jayawickreme - PRIMUM NON NOCERE FIRST DO NO HARM SYMPTOM WORSENING AND IMPROVEMENT INDocument8 pages2014 - Jayawickreme - PRIMUM NON NOCERE FIRST DO NO HARM SYMPTOM WORSENING AND IMPROVEMENT INMarinaNo ratings yet

- Strong Thesis Statement On Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia and The MediaDocument4 pagesStrong Thesis Statement On Anorexia Nervosa and Bulimia and The Mediabk4pfxb7100% (1)

- The Haunted Self Structural Dissociation and The T PDFDocument7 pagesThe Haunted Self Structural Dissociation and The T PDFAngel CosioNo ratings yet

- Abortion Stigma: A Reconceptualization of Constituents, Causes and ConsequencesDocument13 pagesAbortion Stigma: A Reconceptualization of Constituents, Causes and ConsequencesHèliaNo ratings yet

- Wortman Silver 1989 Article1Document10 pagesWortman Silver 1989 Article1SpelliardNo ratings yet

- Restoring Psychology's Role in Peptic Ulcer: Applied Psychology Health and Well-Being March 2013Document24 pagesRestoring Psychology's Role in Peptic Ulcer: Applied Psychology Health and Well-Being March 2013Ioana VoinaNo ratings yet

- DiaCare 2016 Schwartz 179 861Document9 pagesDiaCare 2016 Schwartz 179 861Keenan ArasyidNo ratings yet

- Placebo Effect Thesis StatementDocument7 pagesPlacebo Effect Thesis StatementChristine Williams100% (2)

- Fragilidad en Cuidados IntensivosDocument23 pagesFragilidad en Cuidados IntensivosVlady78No ratings yet

- 2009 PositiveButnotNegativePunishmentPredictsAnxDepAmongProstateCancerPatients BitsikaetalDocument11 pages2009 PositiveButnotNegativePunishmentPredictsAnxDepAmongProstateCancerPatients BitsikaetalJosé Yamil Montañez AgostoNo ratings yet

- Screening For Psychosocial Distress A National SurDocument7 pagesScreening For Psychosocial Distress A National SurAlexNo ratings yet

- Family Needs and Involvement in The Intensive Care Unit AliteratureDocument14 pagesFamily Needs and Involvement in The Intensive Care Unit AliteratureLaia NadeuNo ratings yet

- Lubet 2017 Defense of The Pace Trial Is Based On Argumentation FallaciesDocument5 pagesLubet 2017 Defense of The Pace Trial Is Based On Argumentation FallaciesDiverneetic Herramientas EducativasNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1603670Document23 pagesNihms 1603670Patricio GGNo ratings yet

- Spiritual Coping, Family History, and Perceived Risk For Breast Cancer-Can We Make Sense of It?Document13 pagesSpiritual Coping, Family History, and Perceived Risk For Breast Cancer-Can We Make Sense of It?Rizky KaruniawatiNo ratings yet

- Development of The Bereavement Risk Inventory and Screening Questionnaire (BRISQ) : Item Generation and Expert Panel FeedbackDocument10 pagesDevelopment of The Bereavement Risk Inventory and Screening Questionnaire (BRISQ) : Item Generation and Expert Panel FeedbackShinta PriyanggaNo ratings yet

- Towards A Broader Psychedelic BioethicsDocument7 pagesTowards A Broader Psychedelic BioethicsRiaa GaubaNo ratings yet

- The FNIH Sarcopenia Project: Rationale, Study Description, Conference Recommendations, and Final EstimatesDocument12 pagesThe FNIH Sarcopenia Project: Rationale, Study Description, Conference Recommendations, and Final EstimatesCsenge JeszenszkyNo ratings yet

- A Literature Review of Western Bereavement TheoryDocument6 pagesA Literature Review of Western Bereavement TheoryafmzndvyddcoioNo ratings yet

- Associations Between Adult Attachment Ratings and Health ConditionsDocument8 pagesAssociations Between Adult Attachment Ratings and Health ConditionsAzzurra AntonelliNo ratings yet

- Can HominDocument12 pagesCan HominJuan Paucar FuentesNo ratings yet

- Carel-Phenomenology and PatientsDocument18 pagesCarel-Phenomenology and PatientsW Andrés S MedinaNo ratings yet

- 1993 CollinsetalDocument17 pages1993 CollinsetalGabriela MarcNo ratings yet

- Housing and Mental Health: Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology July 2000Document6 pagesHousing and Mental Health: Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology July 2000Kurt LAUNo ratings yet

- Policy Car PDFDocument9 pagesPolicy Car PDFNaveen ONo ratings yet

- Phaser 3124 - 3125 Service ManualDocument150 pagesPhaser 3124 - 3125 Service Manualgeniusppang50% (2)

- Performance: Task in MarketingDocument4 pagesPerformance: Task in MarketingRawr rawrNo ratings yet

- Natural Gas Weekly UpdateDocument12 pagesNatural Gas Weekly Updateapi-212233479No ratings yet

- Chemical Reaction Engineering 1 BKF 2453 SEM II 2015/2016: Mini ProjectDocument26 pagesChemical Reaction Engineering 1 BKF 2453 SEM II 2015/2016: Mini ProjectSyarif Wira'iNo ratings yet

- BS 4592 1 2006Document2 pagesBS 4592 1 2006gk80823100% (1)

- Painting Procedure JotunDocument9 pagesPainting Procedure Jotunspazzbgt100% (2)

- S9300&S9300E V200R001C00 Hardware Description 05 PDFDocument282 pagesS9300&S9300E V200R001C00 Hardware Description 05 PDFmike_mnleeNo ratings yet

- 2nd MODULE 2 PACKEDDocument21 pages2nd MODULE 2 PACKEDnestor arom sellanNo ratings yet

- Controles de Mod GTA VDocument2 pagesControles de Mod GTA VUNACHNo ratings yet

- Pamphlet On Quality Assurance Planning PSC SleepersDocument6 pagesPamphlet On Quality Assurance Planning PSC SleepersDineshKMPNo ratings yet

- Developing Information System SolutionDocument42 pagesDeveloping Information System SolutionAbhijeet Mahapatra71% (7)

- ADMAS University Institutional Assessment Sector: ICT Occupation: ICT Support Level IDocument5 pagesADMAS University Institutional Assessment Sector: ICT Occupation: ICT Support Level IsssNo ratings yet

- The Secret Behind 432Hz Tuning - Attuned VibrationsDocument2 pagesThe Secret Behind 432Hz Tuning - Attuned VibrationsAdityaCaesarNo ratings yet

- EVS Assignment Question by Vedant Nagpal Answer 03Document1 pageEVS Assignment Question by Vedant Nagpal Answer 03Vedant NagpalNo ratings yet

- Eico 685 Operating ManualDocument29 pagesEico 685 Operating ManualkokoromialosNo ratings yet

- Research Journal of Internatıonal StudıesDocument16 pagesResearch Journal of Internatıonal StudıesShamsher ShirazNo ratings yet

- XLPE/PVC, Low-Voltage Power, Unshielded 600 V, UL Type TC-ER - Method 4 Color CodeDocument1 pageXLPE/PVC, Low-Voltage Power, Unshielded 600 V, UL Type TC-ER - Method 4 Color CodeLEMAGA GROUPNo ratings yet

- The 12 Pillars of CompetitivenessDocument6 pagesThe 12 Pillars of Competitivenessmalinici1No ratings yet

- National Policy Paper - Norway (10.03.2019)Document12 pagesNational Policy Paper - Norway (10.03.2019)simoneNo ratings yet

- Business Branding - The Art of War in The Marketing World With Jun WuDocument1 pageBusiness Branding - The Art of War in The Marketing World With Jun Wusundevil2010usa4605No ratings yet

- Pickle Making 22 July 2019 Syllabus Niesbud NoidaDocument3 pagesPickle Making 22 July 2019 Syllabus Niesbud NoidaTouffiq SANo ratings yet

- Justice Brion's Penned CasesDocument409 pagesJustice Brion's Penned CasesKeking XoniuqeNo ratings yet

- OscillatorsDocument3 pagesOscillatorsDanley Rodrigues DantasNo ratings yet

- 10251company Profile PDFDocument3 pages10251company Profile PDFkavenindiaNo ratings yet

- Language Applied To Volcanic ParticlesDocument3 pagesLanguage Applied To Volcanic Particlesjunior.geologiaNo ratings yet

- Electrolytes CC2 Students CopiesDocument2 pagesElectrolytes CC2 Students CopiesIdkNo ratings yet

- Compound Sentence Exxercises With FANBOYS EsplanDocument3 pagesCompound Sentence Exxercises With FANBOYS EsplanTimothyNo ratings yet

- Character Personality ClothesDocument3 pagesCharacter Personality ClothesMelania AnghelusNo ratings yet

- General: Preferred Jobs To Work (Position(s) You Want To Apply For)Document4 pagesGeneral: Preferred Jobs To Work (Position(s) You Want To Apply For)voodoonsNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsFrom EverandCritical Thinking: How to Effectively Reason, Understand Irrationality, and Make Better DecisionsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (39)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- An Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyFrom EverandAn Autobiography of Trauma: A Healing JourneyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Autoimmune Cure: Healing the Trauma and Other Triggers That Have Turned Your Body Against YouFrom EverandThe Autoimmune Cure: Healing the Trauma and Other Triggers That Have Turned Your Body Against YouNo ratings yet

- Rewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryFrom EverandRewire Your Anxious Brain: How to Use the Neuroscience of Fear to End Anxiety, Panic, and WorryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (158)

- Summary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDFrom EverandSummary of The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk MDRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (167)

- Feel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LoveFrom EverandFeel the Fear… and Do It Anyway: Dynamic Techniques for Turning Fear, Indecision, and Anger into Power, Action, and LoveRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (250)

- My Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesFrom EverandMy Grandmother's Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and BodiesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (70)

- Feeling Great: The Revolutionary New Treatment for Depression and AnxietyFrom EverandFeeling Great: The Revolutionary New Treatment for Depression and AnxietyNo ratings yet

- Breaking the Chains of Transgenerational Trauma: My Journey from Surviving to ThrivingFrom EverandBreaking the Chains of Transgenerational Trauma: My Journey from Surviving to ThrivingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- The Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeFrom EverandThe Upward Spiral: Using Neuroscience to Reverse the Course of Depression, One Small Change at a TimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (141)

- The Worry Trick: How Your Brain Tricks You into Expecting the Worst and What You Can Do About ItFrom EverandThe Worry Trick: How Your Brain Tricks You into Expecting the Worst and What You Can Do About ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (107)

- Summary: No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model by Richard C. Schwartz PhD & Alanis Morissette: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: No Bad Parts: Healing Trauma and Restoring Wholeness with the Internal Family Systems Model by Richard C. Schwartz PhD & Alanis Morissette: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Winning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeFrom EverandWinning the War in Your Mind: Change Your Thinking, Change Your LifeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (561)

- The Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholeFrom EverandThe Complex PTSD Workbook: A Mind-Body Approach to Regaining Emotional Control & Becoming WholeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (49)

- Emotional Detox for Anxiety: 7 Steps to Release Anxiety and Energize JoyFrom EverandEmotional Detox for Anxiety: 7 Steps to Release Anxiety and Energize JoyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (6)

- Redefining Anxiety: What It Is, What It Isn't, and How to Get Your Life BackFrom EverandRedefining Anxiety: What It Is, What It Isn't, and How to Get Your Life BackRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (153)

- Don't Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety AttacksFrom EverandDon't Panic: Taking Control of Anxiety AttacksRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Binaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationFrom EverandBinaural Beats: Activation of pineal gland – Stress reduction – Meditation – Brainwave entrainment – Deep relaxationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (9)

- Somatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionFrom EverandSomatic Therapy Workbook: A Step-by-Step Guide to Experiencing Greater Mind-Body ConnectionNo ratings yet

- How To Get Your Sh!t Together: Overcome Anxiety, Defeat Depression, Move on from Trauma, Get Organised, Find Meaning, Follow Your DreamsFrom EverandHow To Get Your Sh!t Together: Overcome Anxiety, Defeat Depression, Move on from Trauma, Get Organised, Find Meaning, Follow Your DreamsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (8)

- Anxious for Nothing: Finding Calm in a Chaotic WorldFrom EverandAnxious for Nothing: Finding Calm in a Chaotic WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1247)

- Happiness Hypothesis, The, by Jonathan Haidt - Book SummaryFrom EverandHappiness Hypothesis, The, by Jonathan Haidt - Book SummaryRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (95)

- Decluttering at the Speed of Life: Winning Your Never-Ending Battle with StuffFrom EverandDecluttering at the Speed of Life: Winning Your Never-Ending Battle with StuffRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (578)

- Beyond Thoughts: An Exploration Of Who We Are Beyond Our MindsFrom EverandBeyond Thoughts: An Exploration Of Who We Are Beyond Our MindsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)