Professional Documents

Culture Documents

05 3theory

Uploaded by

john rex0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views6 pagesLearning Theories

Original Title

05-3theory

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentLearning Theories

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views6 pages05 3theory

Uploaded by

john rexLearning Theories

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 6

Distance education theory

The need for theory.

We must not hide the fact that there is a great deal of confusion about

terminology in the distance education field. In particular the use of the term

"distance learning" is troublesome since it suggests actions of one person,

i.e. the learner, that are independent of the actions of teachers. Yet every

so-called "distance learning" program is in fact a teaching program as well as

a learning program, and therefore can only correctly be referred to as

distance education. The point is not that the concepts of distance education

have not been defined and explored, nor that there is unanimity among scholars

about their meanings. In this journal there have been several articles that

have contributed to the progress in conceptualization, as well as showing the

areas of disagreement. What is needed is more discussion about and

understanding of these efforts to organize our knowledge, as well as more

careful and thoughtful use of terms. Understanding how we "organize our

knowledge" means to understand our theory. That's what theory is, the

summary

and synthesis of what is known about a field. It is the reduction of our

knowledge to the basic ideas, presented in a way that shows their underlying

patterns and relationships. Understanding theory makes it possible for us to

speak with a common vocabulary. Understanding it should have the effect of

helping practitioners see where their piece of the action fits and interfaces

with others and thus lead to better ways of working with others. The theory

also helps us understand what we don't know, and therefore is the only guide

to research. Research that is not grounded in theory is wasteful. It might

solve an immediate problem, but it doesn't fulfill its promise, because if it

was related to theory it is likely to solve other problems in different times

and different places. In our theorizing we rise above immediate and local

concerns and find out what is general and longlasting. This gives us a broad

perspective that enables us to analyse the particular instance more

effectively; it helps us make decisions that are guided by fundamental

teaching and learning principles, rather than in response to the pressure of a

particular crisis or the dazzle of a fresh opportunity.

Transactional Distance

The first attempt in English to define distance education and to

articulate a theory appeared in 1972 (Moore, 1972) and in 1980 was named as

the theory of transactional distance (Moore, 1980). Analysis of the literature

that was summarized by this theory led to the important postulate that when we

talk about distance education we are referring to a distance that is more than

simply a geographic separation of learners and teachers. It is a distance of

understandings and perceptions, caused in part by the geographic distance,

that has to be overcome by teachers, learners and educational organizations if

effective, deliberate, planned learning is to occur.

The concept of Transaction was derived from Dewey, (Dewey and Bentley,

1949). As explained by Boyd and Apps (1980) it "connotes the interplay among

the environment, the individuals and the patterns of behaviors in a situation"

(page 5). The transaction that we call distance education occurs between

individuals who are teachers and learners, in an environment that has the

special characteristic of separation of one from another, and a consequent set

of special teaching and learning behaviors. It is the physical separation that

leads to a psychological and communications gap, a space of potential

misunderstanding between the inputs of instructor and those of the learner,

and this is the transactional distance. Little is known about transactional

distance and much research is needed to understand it better. What follows are

conjectures that have at least stood the test of over twenty years discussion

among distance education scholars in several countries, and that might be

further elaborated and more formally tested.

It now appears that transactional distance is a continuous rather than a

discrete variable, a relative rather than an absolute term. In any educational

program there is some transactional distance, even where learners and teachers

meet face to face. What is normally referred to as distance education is that

subset of educational programs in which the separation of teacher and learner

is so significant that it affects their behaviors in major ways, and requires

the use of special techniques and leads to special conceptualization. The

relative nature of transactional distance means also that within the sub-set

of educational programs that we call distance education programs there are

many different degrees of transactional distance. When we recognize that

distance education is education, we can apply much that we know about

teaching

and learning from conventional education in both our theory and in the

practice of distance education. In practice, however, we discover that

transactional distance in many programs is so great that the teaching we

deliver cannot be just like conventional teaching. On the contrary, the

transactional distance is such that special organizations and teaching

procedures are essential.

These special teaching procedures fall into two clusters, and what

determines the extent of distance in a program is a function of these two sets

of variables. These are not technological or communications variables, but

variables in teaching and in the interaction of teaching and learning. The two

sets of variables are labelled dialogue and structure.

Dialogue describes the interaction between the teacher and learner when

one gives instruction and the other responds. The extent and nature of this

dialogue is determined by the educational philosophy of the individual or

group responsible for the design of the course, by the personalities of

teacher and learner, by the subject-matter of the course, and by environmental

factors. The most important of these is the medium of communication. For

example, an educational program in which communication between teacher and

learner is solely by television permits no dialogue; the student might make a

response to a teacher, but no consequent response is possible. A program by

correspondence is more dialogic, yet not to the same extent as one taught by

computer conference because of the pace of interaction. Even in programs that

have been described as having no dialogue, such as when the learner is working

with print, audio or video recorded media there is a form of highly structured

learner-instructor dialogue. In such situations the learner's dialogue is with

the person who in some distant place and time organized a set of ideas or

information for transmission to, and interaction with an unknown distant

reader, viewer, or listener. The dialogue that occurs when a learner and an

instructor communicate by an interactive electronic medium is more dynamic

than that between expert and learner using a recorded medium, and programs

that have it, being more highly dialogic and also less structured, are

therefore less distant.

The second set of variables that determine transactional distance are

the elements in the course design, or the ways in which the teaching program

is structured so that it can be delivered through the various communications

media. Programs are structured in different ways to take into account the need

to produce, copy, deliver, and control these mediated messages. Structure

expresses the rigidity or flexibility of the program's educational objectives,

teaching strategies, and evaluation methods. It describes the extent to which

an education program can accommodate or be responsive to each learner's

individual needs. A recorded television program for example is highly

structured, with virtually every activity of the instructor and every minute

of time provided for, and every piece of content pre-determined. There is

little or no opportunity for deviation or variation according to the needs of

a particular individual. This can be compared with many teleconference

courses, which permit a wide range of alternative responses by the instructor

to students' questions and written submissions. In some ways however the

teleconference is more distant than correspondence instruction, since the

individual learner might get more individual, less structured, interaction

through the mail than as member of a large group participating in the

teleconference. The television program is highly structured and teacher-

learner dialogue is non-existant, so that transactional distance is high. In

the correspondence program there is more dialogue and less structure. At the

other extreme, the extent of transactional distance is likely to be relatively

low in those teleconference programs that have much dialogue and little pre-

determined structure.

The above discussion should make it clear that the extent of dialogue

and the flexibility of structure varies from program to program, rather than

from one medium to another. In programs with little transactional distance,

the learner receives directions and guidance through both the structure of the

course and dialogue with an instructor. In more distant programs, learners

have to make their own decisions about study strategies. Even where a course

is structured to give directions and guidance, if there is no dialogue,

students may decide for themselves whether the instructions will be used, and

if so when, where, in what ways, and to what extent. The greater the

transactional distance, the more such autonomy the learner has to exercise.

While learning style is not a characteristic of transactional distance, there

is a relationship between transactional distance and learning style. The

greater the transactional distance, the more autonomy the learner has to

exercise. The determination whether a program will be of greater or less

distance is, as stated earlier, not merely determined by the nature of the

communications medium, but by other significant variables within the

transactional environment, including the social, psychological and

philosophical characteristics of the learner and teacher and the mission of

the educational institution.

What determines the success of distance teaching is the extent to which

the institution and the individual instructor are able to provide the

appropriate opportunity for, and quality of, dialogue between teacher and

learner, as well as appropriately structured learning materials. Frequently

this will mean taking measures to reduce transactional distance by increasing

the dialogue through use of teleconference, and developing well structured

printed support materials. Unfortunately what is appropriate varies according

to content, level of instruction, and learner characteristics, especially the

optimum autonomy the learner can exercise. Much time and effort therefore has

to be devoted to understanding the needs of learner populations, and

individual learners, to analyzing the content to be taught, to determining the

exact learning objectives, the type and frequency of learner exercises and

activities and evaluation procedures, and the relationship between the learner

and instructors. In other words, much care should be given to determine both

the structure of the program and the nature of the dialogue that is sufficient

and appropriate for each set of particular learners, and ideally each

individual learner. There are no quick or ready made answers to the question

of how much dialogue or structure is needed and desirable for effective

learning. Looking for such answers is likely to be a better basis for making

decisions about when and how to use media and other resources than any other

framework available at the present time.

What is needed for the further development of the theory of distance

education? We do not need more labelling or naive descriptions of the

variables that distinguish the field, but we need infilling of the theoretical

spaces that are now apparant. These concern the inter-relationships of

dialogue, structure and autonomy, especially the effects of the new

interactive telecommunications. Several articles that touch on this issue have

been published in this journal. They are the work of Garrison and Shale and

Garrison and Baynton in Canada, Keegan in Australia, and Saba in the United

States. Keegan's ( ) approach has been to review several basic theories and

other writings, including the theory of transactional distance, and to draw

from them what he considers to be the distinguishing characteristics of

distance education. Garrison and Baynton ( ) have taken up the idea of

learner autonomy in their analysis of learner and teacher control, including

an examination of the effect of dialogue and structure on learner control and

autonomy. Saba (1989)has expanded the concept of transactional distance by

using system dynamics to produce a model of the dynamic inter-relationship of

dialogue and structure. He refers to "integrated systems" of telecommunication

media and explains that maximization of dialogue via integrated systems

minimizes transactional distance. These initiatives should lead to the

generation of hypotheses and empirical testing. Empirical research is needed

to test the theory, and empirical research should be better grounded than it

has been in theory. The development of a successful symbiotic relationship

between the two endeavors is in the best interests not only of the researchers

themselves, but ultimately of practitioners and learners also.

References

Boyd, R., J.W. Apps and Associates (1980). Redefining the Discipline of Adult

Education. San Francisco. Jossey Bass.

Dewey, J., and Bentley, A.F.(1949) Knowing and the Known Boston: Beacon

Press.

Garrison, R. and Baynton, M.. (date) Beyond independence in distance

education: the concept of control. The American Journal of Distance Education,

page..

Garrison R. and Shale, D.G. (date) Mapping the Boundaries of distance

education: problems in defining the field. The American Journal of Distance

Education (page)

Keegan, D. (date) Problems in Defining the field of distance education. The

American Journal of Distance Education (page)

Moore,M. (1972) Learner autonomy: The second dimension of independent

learning. Convergence V(2):76-88

Moore, M. (1980) "Independent Study" in Boyd, R., J.W. Apps and Associates

Redefining the Discipline of Adult Education. San Francisco. Jossey Bass.

Saba, F. (date)Integrated telecommunications systems and instructional

transaction. The American Journal of Distance Education (Page)

You might also like

- Pedagogies for Student-Centered Learning: Online and On-GoundFrom EverandPedagogies for Student-Centered Learning: Online and On-GoundRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Moore Trans DistanceDocument10 pagesMoore Trans DistanceJulio Leyva100% (1)

- Moore & Kearsley (2005) Theory of Transactional Distance Theoretical Principles of Distance EducationDocument10 pagesMoore & Kearsley (2005) Theory of Transactional Distance Theoretical Principles of Distance EducationDSNo ratings yet

- Educación A Distancia: de La Teoría A La Práctica: Book Notes - Vol. 3, No. 2Document4 pagesEducación A Distancia: de La Teoría A La Práctica: Book Notes - Vol. 3, No. 2Diego Gomez RojasNo ratings yet

- M.A. Edu. ODL.Document250 pagesM.A. Edu. ODL.Anonymous PKZ0DTwj2No ratings yet

- Distance Education PDFDocument250 pagesDistance Education PDFsyamtripathy1No ratings yet

- Distance EducationDocument8 pagesDistance Educationpavithra GNo ratings yet

- Effective Teaching Around The World: Ridwan Maulana Michelle Helms-Lorenz Robert M. Klassen EditorsDocument793 pagesEffective Teaching Around The World: Ridwan Maulana Michelle Helms-Lorenz Robert M. Klassen Editorszgr2yhf7wpNo ratings yet

- Transfer of Learning in PsychologyDocument19 pagesTransfer of Learning in PsychologyLeu Gim Habana Panugan100% (1)

- Defining Distance Learning and Distance EducationDocument14 pagesDefining Distance Learning and Distance EducationVince NavarezNo ratings yet

- (Group 2) Paper Extended SchoolDocument13 pages(Group 2) Paper Extended SchoolVNabillaNo ratings yet

- Sinem Parlak Sinem Parlak Midterm Paper 89672 282988212Document8 pagesSinem Parlak Sinem Parlak Midterm Paper 89672 282988212api-644206740No ratings yet

- Definitions of Open Distance LearningDocument8 pagesDefinitions of Open Distance LearningOlanrewju LawalNo ratings yet

- Cus 3701 Ass 2Document8 pagesCus 3701 Ass 2Henko HeslingaNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Distance Learning Communication Between Students and Instructors (Research Proposal)Document12 pagesFactors Affecting Distance Learning Communication Between Students and Instructors (Research Proposal)Themis RhysNo ratings yet

- Collaborative LearningDocument7 pagesCollaborative LearningZine EdebNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document3 pagesChapter 1Andrea Nicole ReyNo ratings yet

- Barratt Comprehension OverviewDocument8 pagesBarratt Comprehension OverviewShiro MiyabiNo ratings yet

- Lecture MethodsDocument9 pagesLecture MethodsCriselle Estrada100% (2)

- Mock ArticleDocument7 pagesMock ArticleWinddy Esther Contreras GutiérrezNo ratings yet

- Teaching Methodology: Methods of InstructionDocument5 pagesTeaching Methodology: Methods of Instructionndubissi2010100% (1)

- Educación A Distancia: de La Teoría A La Práctica: Book Notes - Vol. 3, No. 2Document4 pagesEducación A Distancia: de La Teoría A La Práctica: Book Notes - Vol. 3, No. 2Mariana CostaNo ratings yet

- EED 3111 - Edu Tech Lecture 1Document8 pagesEED 3111 - Edu Tech Lecture 1Joan KuriaNo ratings yet

- Reflective Commentary On Chapter 3 - Delos Reyes, MilaDocument3 pagesReflective Commentary On Chapter 3 - Delos Reyes, MilaMILA DELOS REYESNo ratings yet

- hd341 Syllabus sp1 2015Document13 pageshd341 Syllabus sp1 2015api-282907054No ratings yet

- Postmethod EraDocument8 pagesPostmethod EraMuldraugh DreamsNo ratings yet

- W11 - W13 Lesson 6 Communication For Academic Purposes - Module ADocument4 pagesW11 - W13 Lesson 6 Communication For Academic Purposes - Module AShadrach AlmineNo ratings yet

- Cooperative Learnin1Document5 pagesCooperative Learnin1Shaleni LogeswaranNo ratings yet

- 601-9040-Gilbertj-A1 Essay1Document3 pages601-9040-Gilbertj-A1 Essay1api-266857115No ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument5 pagesResearch Paperapi-534682800No ratings yet

- Assignment 3Document31 pagesAssignment 3Mathar BashirNo ratings yet

- Effective Online Instruction Depends On Learning Experiences That Are Appropriately Designed and Facilitated by Knowledgeable EducatorsDocument50 pagesEffective Online Instruction Depends On Learning Experiences That Are Appropriately Designed and Facilitated by Knowledgeable EducatorsMarynel ZaragosaNo ratings yet

- CH 1Document7 pagesCH 1Jewil MeighNo ratings yet

- Ania Lian CILS 2008Document18 pagesAnia Lian CILS 2008Sandro BarrosNo ratings yet

- Lecture Listening in An Ethnographic PerspectiveDocument3 pagesLecture Listening in An Ethnographic PerspectiveHoracio Sebastian LeguizaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument12 pagesUntitledChrishelyn DacsilNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Theories of Learning: Ro RoachesDocument35 pagesUnit 1 Theories of Learning: Ro RoachesSaurabh SatsangiNo ratings yet

- Models of Teaching Unit4Document5 pagesModels of Teaching Unit4short talk tvNo ratings yet

- TTL ReflectionsDocument26 pagesTTL ReflectionsLotis VallanteNo ratings yet

- What Is Role of The Learner?Document6 pagesWhat Is Role of The Learner?Dušica Kandić NajićNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning: What Is Language? Classroom InteractionsDocument20 pagesTeaching and Learning: What Is Language? Classroom InteractionsMegha GeofaniNo ratings yet

- TASK 1 CurriculumDocument6 pagesTASK 1 CurriculumRaimi SyazwanNo ratings yet

- Individual Assignment Philosophy (Ranta Butarbutar)Document11 pagesIndividual Assignment Philosophy (Ranta Butarbutar)Ranta butarbutarNo ratings yet

- Digital Learning Environments: New Possibilities and OpportunitiesDocument19 pagesDigital Learning Environments: New Possibilities and OpportunitiesFritz FerranNo ratings yet

- Distancelearning DefDocument215 pagesDistancelearning DefTom ArrolloNo ratings yet

- Ed 808 Advanced Educational Psychology Dr. BustosDocument6 pagesEd 808 Advanced Educational Psychology Dr. BustosDecember-Anne CabatlaoNo ratings yet

- ACTION RESEARCH PROPOSAL Julie FaithDocument10 pagesACTION RESEARCH PROPOSAL Julie FaithDanica GanzanNo ratings yet

- Constructing Knowledge TogetherDocument11 pagesConstructing Knowledge TogetherjovanaepiNo ratings yet

- Nonverbal Communication (NVC) Is The Transmission of Messages or Signals Through A NonverbalDocument7 pagesNonverbal Communication (NVC) Is The Transmission of Messages or Signals Through A NonverbalJan Lloyd OdruniaNo ratings yet

- Thesis For Da FinalDocument55 pagesThesis For Da FinalMarly Depedran EspejoNo ratings yet

- Beyond SMART A New Framework For Goal SettingDocument21 pagesBeyond SMART A New Framework For Goal SettingHelen LS0% (1)

- Assignment No.1 Course: Curriculum Development and Instruction (838) Semester: Spring, 2021Document10 pagesAssignment No.1 Course: Curriculum Development and Instruction (838) Semester: Spring, 2021Adnan NazeerNo ratings yet

- Methods of ResearchDocument25 pagesMethods of ResearchJohn Lewis SuguitanNo ratings yet

- Learning StylesDocument3 pagesLearning StylesUshani CabralNo ratings yet

- Week 17, Lesson 6-1 - Academic CommunicationDocument4 pagesWeek 17, Lesson 6-1 - Academic CommunicationRee-Jane Bautista MacaraegNo ratings yet

- Communication in Classroom - Group 1Document10 pagesCommunication in Classroom - Group 1Fey'sNo ratings yet

- The Teaching ProfessionDocument17 pagesThe Teaching Professionsabyasachi samal100% (6)

- Classroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsFrom EverandClassroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsNo ratings yet

- Science 8 Quarter 4 Week 1 Long QuizDocument2 pagesScience 8 Quarter 4 Week 1 Long Quizjohn rexNo ratings yet

- English 7 DLL Cot 2Document10 pagesEnglish 7 DLL Cot 2john rexNo ratings yet

- English 7 Q3 DLL JVVDocument33 pagesEnglish 7 Q3 DLL JVVjohn rex100% (1)

- English 7 Q3 WK 1Document3 pagesEnglish 7 Q3 WK 1john rexNo ratings yet

- Depedquezon New Heading Footer 2023Document1 pageDepedquezon New Heading Footer 2023john rexNo ratings yet

- Collaboration in EducationDocument6 pagesCollaboration in Educationjohn rexNo ratings yet

- Intervention Plan MCCDocument6 pagesIntervention Plan MCCjohn rexNo ratings yet

- CNHS HistoryDocument1 pageCNHS Historyjohn rexNo ratings yet

- Authorization LetterDocument2 pagesAuthorization Letterjohn rex100% (1)

- PE and Health 10 Long QuizDocument2 pagesPE and Health 10 Long Quizjohn rexNo ratings yet

- Strat Planning Modules 1 2Document9 pagesStrat Planning Modules 1 2john rexNo ratings yet

- March 1 COM CERT 1Document1 pageMarch 1 COM CERT 1john rexNo ratings yet

- Bionote JVVDocument1 pageBionote JVVjohn rexNo ratings yet

- FactorsaffectinglearningDocument6 pagesFactorsaffectinglearningjohn rexNo ratings yet

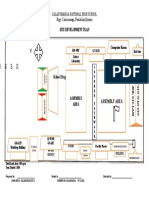

- Calasumanga NHS Evacuation MapDocument1 pageCalasumanga NHS Evacuation Mapjohn rexNo ratings yet

- Depedquezon New Heading Footer 2023Document1 pageDepedquezon New Heading Footer 2023john rex100% (1)

- Updated Action Plan TemplateDocument2 pagesUpdated Action Plan Templatejohn rexNo ratings yet

- Authorization LetterDocument1 pageAuthorization Letterjohn rexNo ratings yet

- Application Letter Kuya PantitDocument1 pageApplication Letter Kuya Pantitjohn rexNo ratings yet

- CNHS LCC Q1Document12 pagesCNHS LCC Q1john rexNo ratings yet

- DLP AnnotationsDocument1 pageDLP Annotationsjohn rexNo ratings yet

- Action Plan MathDocument4 pagesAction Plan Mathjohn rexNo ratings yet

- Day 3 InsetDocument1 pageDay 3 Insetjohn rexNo ratings yet

- CNHS LCC Q2Document12 pagesCNHS LCC Q2john rexNo ratings yet

- Class ScheduleDocument2 pagesClass Schedulejohn rexNo ratings yet

- Atc Cot1Document4 pagesAtc Cot1john rexNo ratings yet

- LLC Ist quate-WPS OfficeDocument2 pagesLLC Ist quate-WPS Officejohn rexNo ratings yet

- Results of Quarterly Assessment in Sy 2022 2023 TemplateDocument128 pagesResults of Quarterly Assessment in Sy 2022 2023 Templatejohn rexNo ratings yet

- Explanation LetterDocument1 pageExplanation Letterjohn rex100% (4)

- Monitoring SheetDocument1 pageMonitoring Sheetjohn rexNo ratings yet

- Centering On Mentoring: A Training Program For Mentors and MenteesDocument21 pagesCentering On Mentoring: A Training Program For Mentors and MenteesMahendran MahendranNo ratings yet

- Field Study 1 To 2Document31 pagesField Study 1 To 2Leznopharya0% (1)

- Task Sheet 1 - The Nature of ReadingDocument3 pagesTask Sheet 1 - The Nature of ReadingErdy John GaldianoNo ratings yet

- Missouri Learning Standards For ELA 2017Document7 pagesMissouri Learning Standards For ELA 2017Cheryl Townsend DickNo ratings yet

- BookDocument20 pagesBookChiriac StefanNo ratings yet

- Formal Observation ReflectionDocument2 pagesFormal Observation Reflectionapi-558106409No ratings yet

- Flow of Communication: Downward, Upward, Horizontal and DiagonalDocument183 pagesFlow of Communication: Downward, Upward, Horizontal and DiagonalEbenezer NdlovuNo ratings yet

- Luka Jarvis English A SBADocument9 pagesLuka Jarvis English A SBALuka JarvisNo ratings yet

- Tess PGP Revised With LogoDocument6 pagesTess PGP Revised With Logoapi-352738700No ratings yet

- Year 5 t1 Unit 1Document5 pagesYear 5 t1 Unit 1api-267136654No ratings yet

- Year 3: Transit FormsDocument15 pagesYear 3: Transit FormsAlia IberahimNo ratings yet

- 5types of Speech StylesDocument24 pages5types of Speech Stylesdanica seraspiNo ratings yet

- Catford's ShiftsDocument104 pagesCatford's ShiftsAhmed EidNo ratings yet

- Windows Phone Taxi Client: Software Requirements SpecificationDocument19 pagesWindows Phone Taxi Client: Software Requirements SpecificationMihai ȘvețNo ratings yet

- Nueva Ecija University of Science and Technology: Sumacab CampusDocument9 pagesNueva Ecija University of Science and Technology: Sumacab CampusBlaireGarciaNo ratings yet

- EPY 702 Students As ResearchersDocument4 pagesEPY 702 Students As ResearchersMary EnwemayaNo ratings yet

- Activity 1Document3 pagesActivity 1Joshua BaguioNo ratings yet

- Social Media 101 Workshop SlidesDocument35 pagesSocial Media 101 Workshop Slidestitan gnagoNo ratings yet

- Article AdoptionTechnology TextEditorialProduction 394 1 10 20190726Document11 pagesArticle AdoptionTechnology TextEditorialProduction 394 1 10 20190726Chiheb KlibiNo ratings yet

- Oral Communication in Context: Semester 1 - Quarter 1 - Module 3: Breaking The BarriersDocument26 pagesOral Communication in Context: Semester 1 - Quarter 1 - Module 3: Breaking The BarriersAshley Gwyneth67% (3)

- Chinese Is Easy TedXDocument3 pagesChinese Is Easy TedXMikhail GedekhauriNo ratings yet

- Definition Development CommunicationDocument10 pagesDefinition Development Communicationsudeshna86No ratings yet

- Students NeedsDocument2 pagesStudents NeedsJonnifer LagardeNo ratings yet

- Safety NetDocument2 pagesSafety Netpaehuihwan8428No ratings yet

- Bilingual Students-Deaf and Hearing - Learn About Science: Using Visual Strategies, Technology and CultureDocument11 pagesBilingual Students-Deaf and Hearing - Learn About Science: Using Visual Strategies, Technology and CultureAya FathyNo ratings yet

- Body Paragraph Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesBody Paragraph Lesson Planapi-532262279No ratings yet

- Korean Language 2A SB SampleDocument21 pagesKorean Language 2A SB SampleKym Tiến0% (5)

- Comparison of ASLDocument14 pagesComparison of ASLSushma PawarNo ratings yet

- DLL Sample FormatDocument30 pagesDLL Sample FormatRUTH MAE GULENGNo ratings yet

- DCP Monitoring Tool Per OUA Memo 00-0422-0121 PART 1Document6 pagesDCP Monitoring Tool Per OUA Memo 00-0422-0121 PART 1Kenneth Dumdum HermanocheNo ratings yet