Professional Documents

Culture Documents

MedJBabylon164340-534105 145010

Uploaded by

Rana RaedOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

MedJBabylon164340-534105 145010

Uploaded by

Rana RaedCopyright:

Available Formats

[Downloaded free from http://www.medjbabylon.org on Saturday, July 1, 2023, IP: 37.238.221.

36]

Original Article

Antiviral Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Infection among

Children and Adolescents with Beta‑Thalassemia Major

Dlair Abdulkhaleq Chalabi, Sawsan Al‑Azzawi

Department of Pediatric, Medical College, Hawler Medical University, Erbil, Iraq

Abstract

Background: Hepatitis C virus (HCV) was encountered as one of the most common infections transmitted through blood transfusion to

thalassemic patients. After the discovery of new generations of antiviral drugs labeled direct‑acting antiviral (DAA) drug since 2014, promising

results were reported compared to older regimen of Peginterferon with or without ribavirin (RBV). Objective: The main objective of the study

is to assess the hepatitis C viral status of multitransfused beta‑thalassemia major patients and the sustained viral response rate to different

modalities of therapy. Materials and Methods: A cross‑sectional analytical study was conducted in Erbil Thalassemia Center. A sample of

all children and adolescent (18 years or younger) patients of beta‑thalassemia major with HCV antibody positive were reviewed according to

the available medical records in the center. They were divided into two groups (first who received interferon ([IFN] ± RBV and second who

received sofosbuvir (SOF) and daclatasvir [DCV]) for the aim of the study. Results: Among registered 695 patients with thalassemia major

screened for HCV antibody, 659 children and adolescents were included and 186 were tested seropositive (28.22%), and they had been submitted

to polymerase chain reaction analysis with HCV‑RNA identified in 110 (59.13% of initially ELISA test positive). IFN‑dependent therapy was

given to 87 patients, while sofosbuvir and DCV for remaining 21 patients, sustained viral response was 100% among those received latter

therapy with no reported relapse compared to former regimen of 44.3% sustained response and 6.33% relapse rate. Conclusion: DAA drug has

a promising therapeutic result replacing the old therapy of IFN‑RBV among thalassemic patients with 100% response rate in the study group.

Keywords: Adolescents, antiviral, children, hepatitis C, thalassemia major

Introduction In Eastern Mediterranean Region, the prevalence of HCV among

the population was variable and range from 1% to 2.5% in most

Beta‑thalassemia major is a well‑known disease requiring

countries, with a high prevalence reported in Egypt (>10%),

frequent blood transfusions, and hepatitis C virus (HCV) was

whereas in Iraq a range of 0.32%–7.1% had been reported. Iraq

encountered as one of the most common infections transmitted

still regarded as a low endemic country for hepatitis B and C.[6,7]

through giving blood. The chance of transmission of infection

has been dramatically decreased since screening of blood The prevalence of HCV Infection among thalassemic patients

donors have been started.[1] range between 12% and 85%.[8] There are few reports in Iraq

about the prevalence of infected patients, In Sulaimania (2009),

Among patients who had received blood frequently before

50% were polymerase chain reaction (PCR) positive for

the 1990s, the rate of HCV infection was found to be

HCV, while it decreased to 26.4% reported by Raham et al.

increased to the number of pints of blood received and

in Diyala.[9,10]

reached 80% in the adult age group.[2,3] Introduction of

vaccine and educational health program lead to significant Genotype testing is widely used for children as well as in

reduction in hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection.[4] It was adults, genetic variability is a distinctive feature of HCV

estimated that around 350–400 million people in the world

are chronic carriers of HBV, which represents approximately Address for correspondence: Dr. Dlair Abdulkhaleq Chalabi,

Department of Pediatric, Medical College, Hawler Medical University, Erbil, Iraq.

7% of the total population, whereas infection with HCV is E‑mail: dulair_chalabi@yahoo.com

found in approximately 3% of the world population, which

represents 160 million people.[5] Submission: 29-05-2019 Accepted: 04-09-2019 Published Online: 23-12-2019

Access this article online This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution‑NonCommercial‑ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix,

Quick Response Code:

tweak, and build upon the work non‑commercially, as long as the author is credited

Website: and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

www.medjbabylon.org

For reprints contact: reprints@medknow.com

DOI: How to cite this article: Chalabi DA, Al-Azzawi S. Antiviral treatment

10.4103/MJBL.MJBL_40_19 of chronic hepatitis C infection among children and adolescents with beta-

thalassemia major. Med J Babylon 2019;16:340-5.

340 © 2019 Medical Journal of Babylon | Published by Wolters Kluwer - Medknow

[Downloaded free from http://www.medjbabylon.org on Saturday, July 1, 2023, IP: 37.238.221.36]

Chalabi and Al‑Azzawi: Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis C

and viral sequences are currently classified into six different Patients with associated other infections such as hepatitis B

genotypes and more than 67 subtypes.[11] Few studies in Iraq or human immune deficiency virus, those with complicated

involved genotyping with variable results, genotype 1 was the cardiopulmonary manifestations or poor compliance to therapy,

most common in a study conducted in Sulaimania (87.5%), or did not complete treatment were excluded from the study.

while Khalid and Abdullah in Mosul revealed that genotype 4

All records of patients were reviewed and data (such as

is the most common subclass (94 of 100, 94%).[10,12]

sociodemographic data, chelation therapy, splenectomy,

The most important issue of hepatitis C infection is when to start hepatitis C genotypes, PCR virus load, doses of antiviral

medical therapy, which is still controversial. Those acutely infected therapy, serum ferritin level, liver function test, and complete

with HCV (usually with no apparent‑specific symptoms) are blood count) were entered for the analysis.

usually children who have normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

Automated platform, LIAISON® XL (DiaSorin S.p.A, Vercelli,

values initially, and they are more likely than adults to recover

Italy) anti‑HCV screening assay, was used to detect positive

from virus spontaneously. [13] Peginterferon (Schering),

immunoblotting results among those patients and positive

interferon (IFN)‑α2b, and ribavirin (RBV) were approved

results were confirmed by PCR testing and then genotyping.

by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in

children older than 3 year of age with HCV hepatitis. Factors Decision of treatment was made according to patient’s age and

increase the response rate are younger age group, genotypes updated guidelines.[16]

(1b, 2 and 3), RNA titer of <2 million copies/mL of blood, and All patients with chronic hepatitis C infection without

viral response (PCR at weeks 4, 12, and even 24 of treatment). cirrhosis who received regular doses of IFN ± RBV

Due to hematological side effects of RBV, sometimes, the (IFN‑2b 1–1. 5 g/kg/week with or without RBV 15 mg/kg/day

treatment will be discontinued and due to reported cases of for 24 or 48 weeks) and those who received DAA (sofosbuvir

spastic diplegia, IFN is not recommended for children below and DCV, standard dose of 400 mg and 60 mg, respectively)

3 year of age.[14,15] were enrolled and divided into two groups according to mode

The updated development in research and experimental of treatment for the aim of the study.

trials started after 2011, and hence, the discovery of the Later, their response will be classified into: early (EVR),

new generations of antiviral drugs labeled direct‑acting sustained (SVR), and no response. PCR was done at

antiviral (DAA) drug established in 2014, such as sofosbuvir 3 months (12 weeks) and at 6 months (24 weeks) to see

polymerase inhibitor (SBV, 2014), simeprevir protease Early Virological Response (EVR) and end treatment

inhibitor (SPV, 2014), and daclatasvir (DCV) NS5A response (normal ALT plus a negative PCR). A Sustained

inhibitor (NS5A, 2014), makes a huge impact in treatment of Virological response (SVR) defined as undetectable

those patients with HCV infection. Then, other new drugs, such HCV‑RNA, 12 weeks or 24 weeks after treatment completion.

as beclabuvir, asunaprevir, ABT450/r + ombitasvir + dasabuvir, Relapse is defined as undetectable HCV‑RNA at the end of

and ledipasvir, were newly approved by the FDA (European treatment but detectable HCV‑RNA during follow‑up.[16,17]

Medicines Agency) in 2014 as a combined single daily dose

tablet (with sofosbuvir approved already by the FDA), with Statistical analysis

the brand name Harvoni.[4] All data were tabulated and arranged in number, proportions,

range (minimum, maximum), and mean ± standard deviation,

Children with HCV genotypes 2 and 3 are more likely to

and the association between variables was measured using

respond to the current treatments, so initiation of early Chi‑square and independent t‑test. P ≤ 0.05 considered to be

treatment is advisable, while genotypes 1 and 4 are less likely statistically significant.

to respond to such therapy.[13]

Ethical consideration

The aim of this study was to assess the hepatitis C viral status

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical

among multitransfused beta‑thalassemia major patients and

principles that have their origin in the Declaration of

the sustained viral response rate (SVR) to different modalities

Helsinki. The study protocol and the subject information and

of antiviral agents.

consent form were reviewed and approved by a Local Ethics

Committee (Medical college/Hawler Medical University).

Materials and Methods After registration in pediatric department, an official letter

This cross‑sectional analytical study was conducted in Erbil was introduced to thalassemia center in Erbil City regarding

Thalassemia Center, Iraq. The center was first established the study.

in 1995 in Rizgary Hospital in Erbil City then became

independent center at 2014 and located in Ankawa District. It Results

receives all patients with hemoglobinpathies and 827 patients

Among registered 695 patients with thalassemia major

were registered including 695 with beta‑thalassemia major.

screened for HCV antibody, 659 children and adolescents

A sample of 186 children and adolescents (18 years or younger) were included according to available data in the center and 186

with beta-thalassemia major were hepatitis C virus positive. were tested seropositive (28.22%), and they were submitted

Medical Journal of Babylon ¦ Volume 16 ¦ Issue 4 ¦ October-December 2019 341

[Downloaded free from http://www.medjbabylon.org on Saturday, July 1, 2023, IP: 37.238.221.36]

Chalabi and Al‑Azzawi: Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis C

to PCR analysis with HCV‑RNA identified in 110 (59.13% of all over Iraq revealed that 13.5% of thalassemia patients had

initially seropositive). HCV infection at some point in their lives during the period

from 2010 to 2015.[20] Recent studies in Diyala and Basra

Those with PCR‑positive results were exposed to antiviral

gives rate of 26.2% and 12.5%, respectively, verify the drop‑in

therapy, two patients did not receive treatment properly and

proportion of infected individuals with thalassemia major.[21,22]

were excluded from the study and 108 patients were included.

Countries like Pakistan and India published data of nearly same

IFN ± RBV was given to 87 patients while sofosbuvir and DCV

for the remaining 21 patients. outcome in this study.[23,24] According to our data, 28.22% were

seropositive and 59.13% of them were PCR‑RNA positive

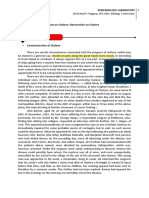

HCV genotype 3 was the most common type (43.6%) followed which is still higher than what have been concluded in recent

by 1 (35.5%), 4 (10.9%), mixed or non‑typeable (7.3%), and studies in Iraq[20,22] and nearby countries like Iran.[25] Turkey

finally 2 (2.7%) as demonstrated in Figure 1. reported lowest rate of 4.4%.[4]

Table 1 demonstrate certain demographic, clinical, and Age at the time of conducting the study may affect many data,

biochemical data of thalassemia patients included in the study, especially the prevalence as younger age groups may give

male constitute largest portion and most of the patients received lower prevalence rate. Male/female ratio was 67/43 among

chelation therapy regularly. No treatment given to 78 patients, PCR‑positive patients, but this was not significant as frequency

while remaining patients received antiviral medication as of male registered in the center already was higher.

stated above.

Genetic variability is a hallmark of HCV and changes according

Splenectomy was observed mainly in PCR‑positive patients to geographical distribution; the Eastern Mediterranean

compared to negative group with significant P = 0.021. ALT Regional Office of the WHO published the collected reports in

level and platelet count were significantly higher among 2016 about the prevalence among population as well as HCV

PCR‑positive group compared to the other group [Table 2]. subtypes and revealed genotype 1 as the most common subtype

Among 110 patients of PCR‑positive HCV, 108 received reported in Iraq followed by 4 and 3.[26] Viral genotyping data in

treatment with appropriate dose, 8 patients of 87 received this study involved only those with thalassemia major indicate

IFN ± RBV did not have any response (no response category). that type 3 as the most common one followed by type 1, and

Early viral response was obtained significantly higher in 18 these results supported by figures recently published in Iran.[25]

of 21 (85.71%) exposed to new regimen therapy compared A total of 70 HCV infected frequently transfused patients with

to 43 of 79 (49.4%) of opposite medication as demonstrated thalassemia major in Duhok were analyzed for genotyping

in Table 3. using genotype‑specific nested PCR, and surprisingly, the

most frequent genotype detected was 4 (52.9%) followed by

3a (17.1%), 1b (12.9%).[27] Other variable reports showed

Discussion

The rates of HCV‑infected thalassemic patients in different

countries range between 12% and 85%.[4] The prevalence had Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the study group

dropped since screening for blood donors had been established, (seropositive for hepatitis C virus)

here in Iraq, it was reported that 66.6% of thalassemic patients Variables Category n (%)

were infected at 1996.[18,19] Later, the prevalence started to Age Mean: 13.85±3.72 186 (100)

decline and a large survey involved adults included 16 centers Median: 15

Gender Male 113 (60.8)

Female 73 (39.2)

HCV Genotypes

Weight Mean: 35.47±11.1 186 (100)

8, 7.3% Median: 35

Consanguinity Yes 107 (57.5)

No 79 (42.5)

12, 10.9% Splenectomy Yes 102 (54.8)

No 84 (45.2)

39, 35.5%

Chelation Rx Regular 163 (87.6)

Irregular or didn’t used 23 (12.4)

48, 43.6% History of first‑degree Positive 132 (71.0)

relative with thalassemia Negative 54 (29.0)

Antiviral therapy No 78 (41.93)

3, 2.7%

IFN ± RBV 87 (46.8)

Sofosbuvir and DCV 21 (11.29)

1 2 3 4 non typable or mixed Serum ferritin at screen time 4731.5±3787 186 (100)

Serum ALT at time of screen 105.19±73.1 186 (100)

Figure 1: Genotyping of 110 patients with hepatitis C virus polymerase ALT: Alanine aminotransferase, IFN: Interferon, RBV: Ribavirin,

chain reaction‑positive testing DCV: Daclatasvir

342 Medical Journal of Babylon ¦ Volume 16 ¦ Issue 4 ¦ October-December 2019

[Downloaded free from http://www.medjbabylon.org on Saturday, July 1, 2023, IP: 37.238.221.36]

Chalabi and Al‑Azzawi: Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis C

Table 2: Comparison of certain variables among polymerase chain reaction‑positive and polymerase chain

reaction‑negative groups

Variables PCR P

Positive (n=110) Negative ((n=76)

Age (mean) 13.88±3.83 13.80±3.57 0.887

Gender, n (%)

Male 67 (60.9) 46 (60.5) 0.958

Female 43 (39.1) 30 (39.5)

Splenectomy, n (%)

Yes 68 (61.8) 34 (44.7) 0.021

No 42 (38.2) 42 (55.3)

Frequency of blood transfusion per year 15.38 ± 4.48 15.53 ±4.65 0.817

Weight, mean±SD 36.49±11.57 34.00±10.28 0.133

ALT, mean±SD 112.70±75.87 74.58±51.14 0.017

AST, mean±SD 107.35±71.31 80.44±60.87 0.074

ALP, mean±SD 305.87±212.32 301.79±296.44 0.946

Serum ferritin, mean±SD 4910.07±4425.3 4480.12±2649.27 0.451

Hemoglobin, mean±SD 9.54±1.14 9.17±0.098 0.033

White blood cells, mean±SD 16,444.40±17,545.40 13,107.02±10,407.58 0.189

Platelet count, mean±SD 536.35±296.60 429.11±246.49 0.021

SD: Standard deviation, PCR: Polymerase chain reaction, ALT: Alanine aminotransferase, AST: Aspartate aminotransferase, ALP: Alkaline phosphatase

by that older age groups in this study received iron‑chelating

Table 3: Early viral response, relapse, and sustained viral

therapy late or irregularly during their illness.[29,30]

response after receiving different antiviral agents

Variables Antiviral treatment P Hemoglobin baseline level was not so important, as it was

variable during phases of treatment due to frequent blood

IFN±RBV Sofosbuvir and

transfusion, but platelet count noticed to be significantly increased

(n=79) DCV (n=21)

in hepatitis C PCR‑positive group, and this may suggest its role

Response of Rx

as an inflammatory marker; however, it needs to be reviewed

EVR* 43 (49.4) 18 (85.71) 0.009

No EVR 36 (41.4) 3 (14.9)

more as controversial reports did not conclude that.[30]

Relapse In this study, following EASL guidelines, SOF‑DCV was

No 74 (93.67) 21 (100) 0.58 among recommended regimen as an empirical therapy for

Yes 5 (6.33) 0 (0) chronic hepatitis c infection (Pangenotypic regimen) and was

SVR

started in the center for those of 12 years or above, while

Yes 35 (44.3) 21 (100) <0.001

younger age groups received old regimen (IFN ± RBV). EVR

No 44 (55.7) 0 (0)

of 3 months was much higher and significant in the SOF‑DCV

*EVR of 3 months. SVR: Sustained virological response, EVR: Early

virological response, IFN: Interferon, RBV: Ribavirin, DCV: Daclatasvir patients (85.71%) compared to 49.4% of IFN ± RBV, and this

strongly recommends the use of former mentioned antiviral

dominant genotype 1 followed by type 3, but most of these therapy, but their efficacy still under trial among younger age

studies lack a large sample size, and this may explain the groups.[30,31]

dissimilarity. Many studies done in Iraq regarding response to therapy and

Splenectomy despite not compared to noninfected groups in biochemical markers was the main indicator of response as

many studies, most of these papers demonstrate that nearly in a study conducted on thalassemic patients in Baghdad

half of infected patients were splenectomized as observed in reviewed effect of IFN ± RBV revealed 10 patients out of

this study and was proved as risk factor for acquiring HCV 21 patients (47%) showed complete response (which defined

infection.[25,28,29] as normalization of ALT levels which usually occurs rapidly,

generally within 2 months of initiation of treatment).[30] A

ALT was significantly higher among infected group with a detailed review in Greece about SVR of infected patients with

mean value of (112.70 ± 75.87), and this could be a good hemoglobinopathies demonstrates 13% failed to respond and

predictor to distinguish infected patients with many studies 40% relapse rate with IFN based therapy which is still higher

have just about same mean value.[29] than our data of 6.33% with IFN ± RBV therapy.[32]

Baseline serum ferritin level was surprisingly higher compared HCV‑DAAs were first licensed in Europe in 2014, and first

to previously published papers, and this could be explained three drugs (sofosbuvir, simeprevir, and DCV) had a SVR of

Medical Journal of Babylon ¦ Volume 16 ¦ Issue 4 ¦ October-December 2019 343

[Downloaded free from http://www.medjbabylon.org on Saturday, July 1, 2023, IP: 37.238.221.36]

Chalabi and Al‑Azzawi: Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis C

60%–100% in infected adults and is considered as affective 6. Alsamarai AM, Abdulrazaq G, Alobaidi AH. Seroprevalence of hepatitis

therapy for all genotypes in noncirrhotic chronic HCV infection.[32] C virus in Iraqi population. JOJ Immuno Virol 2016;1:1‑9.

7. World Health Organization. Viral Hepatitis. Available from: http://

SVR among nonthalassemic HCV‑positive patients had www.emro.who.int/irq/programmes/hepatitis.html. [Last accessed on

2017 Mar 10].

improved dramatically since 1986 with the introduction of 8. Alter MJ, Kruszon‑Moran D, Nainan OV, McQuillan GM, Gao F,

6‑month IFN monotherapy from 6% to 55% after 12 months Moyer LA, et al. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the

of IFN ± RBV combination therapy at 2002 and reached nearly United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med 1999;341:556‑62.

100% with IFN‑free DAA introduction.[33] 9. Kareem BO, Salih GF. Hepatitis C Virus genotyping in Sulaimani

Governorate. Eur Sci J 2014;10:377‑88.

SVR in this study reached 100% with DAA new therapy 10. Raham TF, Abdul Wahed SS, Alhaddad HN. Prevalence of hepatitis

group compared to 44.3% of the other group, unfortunately, C among patients with βthalasemia in Diyala‑Iraq. AL‑TAQANI

2011;24:113‑20.

comparable results regarding new regimen on infected 11. Smith DB, Bukh J, Kuiken C, Muerhoff AS, Rice CM, Stapleton JT,

thalassemic patients were limited due to older age group et al. Expanded classification of hepatitis C virus into 7 genotypes and

trials (>18 year) and most published papers studied SVR of 67 subtypes: Updated criteria and genotype assignment web resource.

genotypes as response varied according to the type and drugs. Hepatology 2014;59:318‑27.

12. Khalid MD, Abdullah BA. Hepatitis C Virus Genotypes in Iraq. Iraqi J

Responses of different genotypes restricted by small sample Biotech 2012;11:475‑80.

13. Fifi A, Barreto A, Delgado‑Borrego A. Optimal management of

size in this study, especially of SOF‑DCV therapy as 2 or less

pediatric hepatitis C infection: A review. Pediatric Health Med Ther

have genotypes 2, 4, or mixed. 2014;5:173‑84.

14. Jensen MK, Balistreri WF. Viral hepatitis. In: Kliegman RM,

Limitation of the study was lack of histological data, as most Stanton MD, Geme JS, Schor NF, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics.

patients did not exposed to liver biopsy and hence Hepatitis 20th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016. p. 1942‑53.

Activity Index grading and score was not applied, ended with 15. Barlow CF, Priebe CJ, Mulliken JB, Barnes PD, Mac Donald D,

empirical treatment regardless the histological features. Very Folkman J, et al. Spastic diplegia as a complication of interferon alfa‑2a

treatment of hemangiomas of infancy. J Pediatr 1998;132:527‑30.

few studies involved thalassemic patients even among adults 16. The European Association for the Study of Liver. EASL recommendations

make it hard to compare our results with previous articles. on treatment of hepatitis C. J Hepatol 2017;66:153‑94.

17. Poordad FF, Flamm SL. Virological relapse in chronic hepatitis C.

Antivir Ther 2009;14:303‑13.

Conclusion 18. Al‑Hilli H, Ghadhban JM. Prevalence of serological markers of hepatitis

DAA has a promising therapeutic result replacing the old B virus (HBsAg) and hepatitis C virus (HCV AB) among blood donors

and certain risk groups. J Fac Med Baghdad 2000;42:709‑15.

therapy of IFN ± RBV among thalassemic patients with 100% 19. Ansar MM, Kooloobandi A. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection

SVR in the study group. These results need to be supported in thalassemia and haemodialysis patients in North Iran‑Rasht. J Viral

by further studies with larger sample size, especially for the Hepat 2002;9:390‑2.

new therapy of SOF‑RBV and other DAA trials including 20. Kadhim KA, Baldawi KH, Lami FH. Prevalence, incidence, trend, and

complications of thalassemia in Iraq. Hemoglobin 2017;41:164‑8.

younger age groups. 21. Noaman NG. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among blood

donors and certain risky groups in Diyala Province. Diyala J Med

Recommendations 2012;2:46‑52.

These results need to be supported by further studies with larger 22. Najim OA, Hassan MK. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus seropositivity

sample size, especially for the new therapy of SOF‑RBV in among multitransfused patients with hereditary anemias in Basra, Iraq.

children of younger age groups. Iraqi J Hematol 2018;7:39‑44.

23. Khattak UD, Shah M, Ahmed I, Rehman A, Sajid M. Frequency of

Financial support and sponsorship hepatitis B and hepatitis C in multitransfused beta thalassaemia major

patients in district Swat. J Saidu Med Coll 2013;3:299‑302.

Nil. 24. Aritra B, Kahini S, Rushna F, Kallol S, Debanjali G, Ghosh M,

et al. Prevalence of anti‑HCV, HBsAg, HIV among multi‑transfused

Conflicts of interest thalassemic individuals and their socio‑economic background in Eastern

There are no conflicts of interest. India. Asian J Pharm Clin Res 2016;9:290‑4.

25. Ahmadi‑Ghezeldasht S, Badiei Z, Sima HR, Hedayati‑Moghaddam MR,

Habibi M, Khamooshi M, et al. Distribution of hepatitis C virus

References genotypes in patients with major β‑thalassemia in Mashhad, Northeast

1. Zamani F, Shakeri R, Islam M, Taheri H, Mohamadnejad M, Iran. Middle East J Dig Dis 2018;10:35‑9.

Malekzadeh R. Interferon monotherapy in major thalassemic patients 26. Sadeghi F, Salehi‑Vaziri M, Almasi‑Hashiani A, Gholami‑Fesharaki M,

with hepatitis C infection. Govaresh 2005;10:178‑82. Pakzad R, Alavian SM. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus genotypes

2. Angelucci E. Antibodies to hepatitis C virus in thalassemia. among patients in countries of the eastern mediterranean regional office

Haematologica 1994;79:353‑5. of WHO (EMRO): A systematic review and meta‑analysis. Hepat Mon

3. Wonke B, Hoffbrand AV, Brown D, Dusheiko G. Antibody to hepatitis 2016;16:e35558.

C virus in multiply transfused patients with thalassaemia major. J Clin 27. Othman AA, Eissa AA, Markous RD, Ahmed BD, Al‑Allawi NA.

Pathol 1990;43:638‑40. Hepatitis C virus genotypes among multiply transfused

4. The European Association for the Study of Liver. Viral Hepatitis C in hemoglobinopathy patients from Northern Iraq. Asian J Transfus Sci

Thalassemia. Geneva: The European Association for the Study of Liver; 2014;8:32‑4.

2016. p. 1‑36. 28. Jang TY, Lin PC, Huang CI, Liao YM, Yeh ML, Zeng YS, et al.

5. Tarky MA, Akram W, Al‑Naaimi SA, Omer AR. Epidemiology of viral Seroprevalence and clinical characteristics of viral hepatitis in

hepatitis B and C in Iraq: A national survey 2005‑2006. Zanco J Med Sci transfusion‑dependent thalassemia and hemophilia patients. PLoS One

2013;17:370‑80. 2017;12:e0178883.

344 Medical Journal of Babylon ¦ Volume 16 ¦ Issue 4 ¦ October-December 2019

[Downloaded free from http://www.medjbabylon.org on Saturday, July 1, 2023, IP: 37.238.221.36]

Chalabi and Al‑Azzawi: Antiviral treatment of chronic hepatitis C

29. Kalafateli M, Kourakli A, Gatselis N, Lambropoulou P, Thomopoulos K, C viral infection in thalassemic children: Clinical and molecular studies.

Tsamandas A, et al. Efficacy of interferon A‑2b monotherapy in Pediatr Res 1996;39:323‑8.

Β‑thalassemics with chronic hepatitis C. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 32. Zachou K, Arvaniti P, Gatselis NK, Azariadis K, Papadamou G,

2015;24:189‑96. Rigopoulou E, et al. Patients with haemoglobinopathies and chronic

30. Ghadban JM, Sayah HA. Clinical, biochemical and histopathological hepatitis C: A real difficult to treat population in 2016? Mediterr J

outcome of six months of interferon therapy in thalassemic patients with Hematol Infect Dis 2017;9:e2017003.

chronic hepatitis C viral infection. Karbala J Med 2007;1:190‑6. 33. Angelucci E, Pilo F. Treatment of hepatitis C in patients with thalassemia.

31. Ni YH, Chang MH, Lin KH, Chen PJ, Lin DT, Hsu HY, et al. Hepatitis Haematologica 2008;93:1121‑3.

Medical Journal of Babylon ¦ Volume 16 ¦ Issue 4 ¦ October-December 2019 345

You might also like

- Upper Limb OrthosisDocument83 pagesUpper Limb OrthosisAwaisNo ratings yet

- Viral Hepatitis in Pregnancy PDFDocument15 pagesViral Hepatitis in Pregnancy PDFBerri RahmadhoniNo ratings yet

- Skin CancerDocument24 pagesSkin CancerMister David anthonyNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Nursing Care (Case Study)Document37 pagesPediatric Nursing Care (Case Study)mira utami ningsih80% (46)

- Research Paper On HCV PDFDocument4 pagesResearch Paper On HCV PDFgw259gj7100% (1)

- Epidemiology of HCV in Saudi Arabia and Its Burden On The Health Care SystemDocument3 pagesEpidemiology of HCV in Saudi Arabia and Its Burden On The Health Care SystemMill LenniumNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Overt and Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infections Among 135Document8 pagesPrevalence of Overt and Occult Hepatitis B Virus Infections Among 135د. مسلم الدخيليNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis Delta Infection - Current and New Treatment OptionsDocument7 pagesHepatitis Delta Infection - Current and New Treatment OptionsDiana Carolina di Filippo VillaNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Hepatitis B Treatment: Haruki Komatsu, Ayano Inui, Tomoo FujisawaDocument13 pagesPediatric Hepatitis B Treatment: Haruki Komatsu, Ayano Inui, Tomoo FujisawaDarmawan HariyantoNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On HCV PDFDocument5 pagesResearch Papers On HCV PDFafmdcwfdz100% (1)

- Clinical Liver Disease - 2013 - Jonas - Hepatitis B Virus Infection in ChildrenDocument4 pagesClinical Liver Disease - 2013 - Jonas - Hepatitis B Virus Infection in ChildrenHạnh NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Chemiluminescent Microparticle Immunoassay Based Detection and Prevalence of HCV Infection in District Peshawar PakistanDocument5 pagesChemiluminescent Microparticle Immunoassay Based Detection and Prevalence of HCV Infection in District Peshawar PakistanMariaNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis C Virus: Screening, Diagnosis, and Interpretation of Laboratory AssaysDocument8 pagesHepatitis C Virus: Screening, Diagnosis, and Interpretation of Laboratory AssaysCristafeNo ratings yet

- Abbas 2014Document6 pagesAbbas 2014Apotik ApotekNo ratings yet

- Early Detection of Unhealthy Behaviors, The Prevalence and Receipt of Antiviral Treatment For Disabled Adult Hepatitis B and C CarriersDocument7 pagesEarly Detection of Unhealthy Behaviors, The Prevalence and Receipt of Antiviral Treatment For Disabled Adult Hepatitis B and C CarriersNabillaNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Virus Infections at Premarital Screening Program in Duhok, IraqDocument11 pagesPrevalence of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C Virus Infections at Premarital Screening Program in Duhok, IraqAliA.RamadhanNo ratings yet

- WJT 8 84 PDFDocument14 pagesWJT 8 84 PDFadan2010No ratings yet

- Smith 2020Document10 pagesSmith 2020senaNo ratings yet

- Vassilopoulos 2002Document13 pagesVassilopoulos 2002deliaNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) : A Review On Its Prevalence and Infection in Different Areas of IraqDocument8 pagesHepatitis B Virus (HBV) : A Review On Its Prevalence and Infection in Different Areas of IraqKanhiya MahourNo ratings yet

- Management of Hepatitis B in Pregnant Women and Infants: A Multicentre Audit From Four London HospitalsDocument8 pagesManagement of Hepatitis B in Pregnant Women and Infants: A Multicentre Audit From Four London HospitalsXenia Marie Razalo LawanNo ratings yet

- Immunology 1Document9 pagesImmunology 1Alexandra Duque-DavidNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis of Viral Hepatitis: ReviewDocument13 pagesDiagnosis of Viral Hepatitis: ReviewReza Redha AnandaNo ratings yet

- Research Gaps in Viral HepatitisDocument6 pagesResearch Gaps in Viral HepatitisMuhammad Anwer QambraniNo ratings yet

- s12879 021 06459 ZDocument11 pagess12879 021 06459 ZCliff Daniel DIANZOLE MOUNKANANo ratings yet

- Virus HVB Host TestingDocument8 pagesVirus HVB Host Testingmariano villavicencioNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis BBB PDFDocument12 pagesHepatitis BBB PDFRizki Cah KeratonNo ratings yet

- Viral Hepatitis in Children.7 PDFDocument6 pagesViral Hepatitis in Children.7 PDFAMENDBENo ratings yet

- Hepatite CDocument12 pagesHepatite CSCIH HFCPNo ratings yet

- Chen Y - Environmental-Ofac128Document10 pagesChen Y - Environmental-Ofac128mecyalvindaNo ratings yet

- 05 - Hepatitis B Virus Infection - Lancet 2014Document11 pages05 - Hepatitis B Virus Infection - Lancet 2014Jmv VegaNo ratings yet

- The Gift of A Lifetime: Analysis of HIV at Autopsy: Frank MaldarelliDocument5 pagesThe Gift of A Lifetime: Analysis of HIV at Autopsy: Frank MaldarelliIrina TănaseNo ratings yet

- HBV-HCV Coinfection: Viral Interactions, Management, and Viral ReactivationDocument10 pagesHBV-HCV Coinfection: Viral Interactions, Management, and Viral ReactivationFiorella Portella CordobaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Direct-Acting Antivirals in Treatment of Elderly Egyptian Chronic Hepatitis C PatientsDocument11 pagesEffectiveness of Direct-Acting Antivirals in Treatment of Elderly Egyptian Chronic Hepatitis C PatientsMostafa SalahNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Case ControlDocument5 pagesJurnal Case ControlRheaNo ratings yet

- Seminar: Daniel P Webster, Paul Klenerman, Geoff Rey M DusheikoDocument12 pagesSeminar: Daniel P Webster, Paul Klenerman, Geoff Rey M Dusheikovira khairunisaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review of Hepatitis B VirusDocument4 pagesLiterature Review of Hepatitis B Virusbaduidcnd100% (1)

- Literature Review On HBVDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On HBVc5r08vf7100% (1)

- HEPATITIS B Thesis PDF: September 2019Document34 pagesHEPATITIS B Thesis PDF: September 2019AmiRa Adel EzelldenNo ratings yet

- Pathogenic Mechanisms in HBV-and HCV-associated Hepatocellular CarcinomaDocument13 pagesPathogenic Mechanisms in HBV-and HCV-associated Hepatocellular CarcinomaJosé MateusNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis C Virus Replication and Potential Targets For Direct-Acting AgentsDocument11 pagesHepatitis C Virus Replication and Potential Targets For Direct-Acting AgentsWael Abdel-MageedNo ratings yet

- Original Article: Magnitude of Cryptococcal Antigenemia 369Document6 pagesOriginal Article: Magnitude of Cryptococcal Antigenemia 369MegbaruNo ratings yet

- Immunology of Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis C Virus InfectionDocument15 pagesImmunology of Hepatitis B Virus and Hepatitis C Virus InfectionMark BowlerNo ratings yet

- Bohlius, 2018Document8 pagesBohlius, 2018Leonardo Arévalo MoraNo ratings yet

- J Ejogrb 2020 11 052Document10 pagesJ Ejogrb 2020 11 052taki takiwNo ratings yet

- Bioscientific Review (BSR) : Age-Wise and Gender-Wise Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection in Lahore, PakistanDocument9 pagesBioscientific Review (BSR) : Age-Wise and Gender-Wise Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection in Lahore, PakistanUMT JournalsNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1038866Document12 pagesNihms 1038866ibnu annafiNo ratings yet

- Kenya High Risk GroupsDocument8 pagesKenya High Risk GroupsjackleenNo ratings yet

- Seminar: Wen-Juei Jeng, George V Papatheodoridis, Anna S F LokDocument14 pagesSeminar: Wen-Juei Jeng, George V Papatheodoridis, Anna S F LokCristian AGNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B, C and DDocument13 pagesHepatitis B, C and DMehiella SatchiNo ratings yet

- HCV PHD ThesisDocument8 pagesHCV PHD Thesistpynawfld100% (2)

- Background: Cirrhosis Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)Document24 pagesBackground: Cirrhosis Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC)Ignatius Rheza SetiawanNo ratings yet

- HCVriskBlood - Lakkana 1Document1 pageHCVriskBlood - Lakkana 1api-26295875No ratings yet

- 05 - CL Bioch 2008Document7 pages05 - CL Bioch 2008sunilpkumar18No ratings yet

- Hepatitis B Virus DissertationDocument7 pagesHepatitis B Virus DissertationWebsiteThatWillWriteAPaperForYouUK100% (1)

- Hepatitis B and C Coinfection in A Real-Life Setting: Viral Interactions and Treatment IssuesDocument6 pagesHepatitis B and C Coinfection in A Real-Life Setting: Viral Interactions and Treatment IssuesFiorella Portella CordobaNo ratings yet

- Ahmad Ali ZahidDocument24 pagesAhmad Ali Zahidhareem555No ratings yet

- Medical Progress: H C V IDocument16 pagesMedical Progress: H C V IriahNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis C Virus Infection: Prevention and Control - A Mini ReviewDocument13 pagesHepatitis C Virus Infection: Prevention and Control - A Mini ReviewBaru Chandrasekhar RaoNo ratings yet

- Medical Progress: H C V IDocument16 pagesMedical Progress: H C V ITrisya Bella FibriantiNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B Virus Infection: Current Status: Ponsiano Ocama, MD, Christopher K. Opio, MD, William M. Lee, MDDocument8 pagesHepatitis B Virus Infection: Current Status: Ponsiano Ocama, MD, Christopher K. Opio, MD, William M. Lee, MDLangitBiruNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus Infection Serologic Markers Among Blood Donors at Federal Medical Center, Keffi, Nasarawa State, NigeriaDocument17 pagesPrevalence of Hepatitis B Virus Infection Serologic Markers Among Blood Donors at Federal Medical Center, Keffi, Nasarawa State, NigeriaIJMSRTNo ratings yet

- Hepatitis B Virus and Liver DiseaseFrom EverandHepatitis B Virus and Liver DiseaseJia-Horng KaoNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Thrombin Activatable Fibrinolysis Inhibitor (TAFI) in Patients with β-ThalassemiaDocument6 pagesEvaluation of Thrombin Activatable Fibrinolysis Inhibitor (TAFI) in Patients with β-ThalassemiaRana RaedNo ratings yet

- PDF 1202Document18 pagesPDF 1202Rana RaedNo ratings yet

- Kanavaki 2009Document5 pagesKanavaki 2009Rana RaedNo ratings yet

- 3 Dfa 6 DC 7 Ec 55 F 9 CCDocument7 pages3 Dfa 6 DC 7 Ec 55 F 9 CCRana RaedNo ratings yet

- Course of FCDocument2 pagesCourse of FCRana RaedNo ratings yet

- Implementation of Innovative Medical TechnologiesDocument18 pagesImplementation of Innovative Medical TechnologiesGregorius HocevarNo ratings yet

- Types of Veneers in Dental WorldDocument6 pagesTypes of Veneers in Dental WorldLenutza LenutaNo ratings yet

- Lethal Genes - Learn Science at ScitableDocument2 pagesLethal Genes - Learn Science at ScitablePaulina CisnerosNo ratings yet

- 11 Ways Women's Heart Attacks Are Different From Men'sDocument25 pages11 Ways Women's Heart Attacks Are Different From Men'sSri KondabattulaNo ratings yet

- 2013-14 Rotary Annual Report PDFDocument32 pages2013-14 Rotary Annual Report PDFAmri KosmarNo ratings yet

- 2022 May CHN CD 1 TeamsDocument8 pages2022 May CHN CD 1 TeamsCrystal Ann TadiamonNo ratings yet

- Accuracy of The GLIM Criteria and SGA Compared To PG-SGA For The Diagnosis of Malnutrition and Its Impact On Prolonged Hospitalization A ProspectiveDocument13 pagesAccuracy of The GLIM Criteria and SGA Compared To PG-SGA For The Diagnosis of Malnutrition and Its Impact On Prolonged Hospitalization A Prospectiveozlemyilmaz1820No ratings yet

- Edexcel Unit 1 Notes Cystic FibrosisDocument2 pagesEdexcel Unit 1 Notes Cystic FibrosisIllharm Sherrif100% (2)

- Group 1 - Posterior Disk Bulge at L5-S1 With Bilateral Severe Neural Canal Narrowing PDFDocument7 pagesGroup 1 - Posterior Disk Bulge at L5-S1 With Bilateral Severe Neural Canal Narrowing PDFKatNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Introduction and HistoryDocument37 pagesChapter 1 - Introduction and HistoryTwinkle ParmarNo ratings yet

- 19BMS134 - Divyajeet Singh'Document63 pages19BMS134 - Divyajeet Singh'Divyajeet SinghNo ratings yet

- CementumDocument10 pagesCementumviolaNo ratings yet

- QPAMBPHARM17Document147 pagesQPAMBPHARM17Sheelendra Mangal Bhatt0% (1)

- Case Study: Epidemiology LaboratoryDocument5 pagesCase Study: Epidemiology LaboratoryDonna IlarNo ratings yet

- Indian Health Diabetes Best Practice Foot Care: Revised July 2009Document29 pagesIndian Health Diabetes Best Practice Foot Care: Revised July 2009AMALIA PEBRIYANTINo ratings yet

- Cue Card QuestionsDocument6 pagesCue Card QuestionsMahaz SadiqNo ratings yet

- Autoimmunity and ToleranceDocument17 pagesAutoimmunity and Toleranceapi-19969058No ratings yet

- Nina Rajan Pillai & Ors. Vs Union of India and Ors. On 13 May, 2011Document33 pagesNina Rajan Pillai & Ors. Vs Union of India and Ors. On 13 May, 2011Sanjayan KizhakkedathuNo ratings yet

- Convert CSVDocument2,498 pagesConvert CSVSunnt BandiNo ratings yet

- Primary and SecondaryDocument5 pagesPrimary and SecondaryDana LebadaNo ratings yet

- Love To Fear You - Kati McRaeDocument310 pagesLove To Fear You - Kati McRaeKlee IdkNo ratings yet

- Disaster Preparation and Management For The Intensive Care UnitDocument9 pagesDisaster Preparation and Management For The Intensive Care UnitSid DhayriNo ratings yet

- TPT Talking Points BookletDocument9 pagesTPT Talking Points BookletNasasira BensonNo ratings yet

- GEHC Invenia ABUS Breast Density InfoDocument2 pagesGEHC Invenia ABUS Breast Density InfoCarmen Suárez GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Biomecanica Da ObesidadeDocument9 pagesBiomecanica Da ObesidadehgtrainerNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Abnormal Psychology 7th Edition Thomas F OltmannsDocument36 pagesTest Bank For Abnormal Psychology 7th Edition Thomas F Oltmannscervusgrowl.bvifwf100% (48)

- 2022 Fall Chem 183 001 20220827 - 140025 - Zoom - 43735.CCDocument14 pages2022 Fall Chem 183 001 20220827 - 140025 - Zoom - 43735.CCjennifer hollandNo ratings yet