Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Describing The Profile of Diagnostic Features in A

Uploaded by

vcuadrosvOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Describing The Profile of Diagnostic Features in A

Uploaded by

vcuadrosvCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:5036–5046

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04214-7

ORIGINAL PAPER

Describing the Profile of Diagnostic Features in Autistic Adults

Using an Abbreviated Version of the Diagnostic Interview for Social

and Communication Disorders (DISCO‑Abbreviated)

Sarah J. Carrington1,2 · Sarah L. Barrett2 · Umapathy Sivagamasundari3 · Christine Fretwell4 · Ilse Noens5,6 ·

Jarymke Maljaars5,6,7 · Susan R. Leekam2

Published online: 7 September 2019

© The Author(s) 2019

Abstract

The rate of diagnosis of autism in adults has increased over recent years; however, the profile of behaviours in these indi-

viduals is less understood than the profile seen in those diagnosed in childhood. Better understanding of this profile will be

essential to identify and remove potential barriers to diagnosis. Using an abbreviated form of the Diagnostic Interview for

Social and Communication Disorders, comparisons were drawn between the profile of a sample of able adults diagnosed in

adulthood and the profile of a sample of able children. Results revealed both similarities and differences. A relative strength

in non-verbal communication highlighted a potential barrier to diagnosis according to DSM-5 criteria for the adult sample,

which may also have prevented them from being diagnosed as children.

Keywords Autism spectrum disorder · DSM-5 · Adult · Diagnosis

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental et al. 2006; Baron-Cohen et al. 2009; Brugha et al. 2011,

disorder affecting more than 1% of the population (e.g. Baird 2016). Although the most recent publication of the Diag-

nostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorder (DSM-

Electronic supplementary material The online version of 5; American Psychiatric Association 2013) recognises that

this article (doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-019-04214-7) symptoms may not become evident until later in life, individ-

contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized uals seeking diagnosis as adults may present with a different

users.

profile of features compared to those diagnosed as children.

* Sarah J. Carrington Differences in the adult behavioural profile of ASD may

s.carrington@aston.ac.uk present as reduced frequency of symptoms compared with

1

childhood, as symptom frequency is known to decline with

Department of Psychology, School of Life and Health

age (Charman et al. 2017; Fecteau et al. 2003; Fountain et al.

Sciences, Aston University, Birmingham B4 7ET, UK

2

2012; Seltzer et al. 2004; Szatmari et al. 2015), particularly

School of Psychology, Wales Autism Research Centre,

in those who have language ability and intellectual ability

University of Cardiff, Cardiff CF10 3AT, UK

3

within the normal range (e.g. McGovern and Sigman 2005;

St Cadoc’s Hospital, Aneurin Bevan University Health

Shattuck et al. 2007). However, little is known about the

Board, Lodge Road, Caerleon NP18 3XQ, UK

4

distinctiveness of the ASD profile in individuals present-

Integrated Autism Service, Unit 10 Torfaen Business Centre, ing for diagnosis in adulthood. Studies examining the adult

Aneurin Bevan University Health Board, Panteg Way, New

Inn, Caerleon NP4 0LS, UK profile have examined patterns of behaviour in individuals

5 who were already diagnosed in childhood or adolescence,

Parenting and Special Education Research Unit, KU Leuven,

Leopold Vanderkelenstraat 32, Bus 3765, 3000 Leuven, not those who first presented for diagnosis in adulthood,

Belgium and the results of such studies are equivocal. For example, a

6

Leuven Autism Research (LAuRes), KU Leuven, Leopold follow up study by Billstedt et al. (2007) of individuals diag-

Vanderkelenstraat 32, Bus 3765, 3000 Leuven, Belgium nosed with ASD in childhood or early adolescence showed

7

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, UPC Z.org KU Leuven, that difficulties in social interaction were more common in

Herestraat 49, 3000 Leuven, Belgium late adolescence and early adulthood than any of the other

13

Vol:.(1234567890)

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:5036–5046 5037

behaviours assessed, including both restricted and repetitive 2014). The profile of behaviours in this adult sample was

behaviours (RRBs) and non-verbal communication difficul- analysed in two ways. First, in terms of the percentage of

ties. In contrast a study by Shattuck et al. (2007) of adults items within each of the DSM-5 subdomains and second as

first diagnosed as children or adolescents also found fewer the percentage of individuals meeting the threshold level

RRBs in adults than younger individuals, but unlike Billstedt that indicated the presence of the symptom being measured

et al. (2007), found more non-verbal communication difficul- in that subdomain. These combined approaches, therefore,

ties in adults than in children. While both of these studies allowed investigation not only of the number of ‘difficul-

suggest greater persistence of social interaction difficulties ties’ in each behavioural subdomain, but also provided an

than RRBs into adulthood in individuals diagnosed during indication of whether these difficulties were considered to

childhood or adolescence, they do not necessarily reflect present significant impairment. Finally, the percentage of

the profile that could characterise those who do not seek a individuals who exhibited behaviours within a DSM-5 algo-

diagnosis until adulthood. rithm previously identified as being highly discriminating

Understanding of the adult profile also needs particular for individuals with ASD (the ‘signposting set’; Carrington

consideration in terms of how behavioural features in adult- et al. 2015) was examined. The results from this adult sam-

hood align with diagnostic criteria. Detailed description can ple were compared with the results previously published for

identify potential diagnostic markers distinctive in adults, children (Carrington et al. 2015; Carrington et al. 2014).

and clarify concerns regarding potential barriers to obtaining

a DSM-5 diagnosis of ASD (e.g. Wilson et al. 2013). There

is evidence, however, that the most recently published diag- Method

nostic criteria—DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association

2013)—may lack sensitivity for more able individuals (e.g. Participants

McPartland et al. 2012; Taheri and Perry 2012; see Kulage

et al. 2014 for alternative finding) and adults (Wilson et al. Participants were 71 adults with clinically diagnosed ASD

2013). Several studies have explored whether sensitivity (mean age = 34.89 years SD 12.32; range 18–63; 46 male,

could be improved by ‘relaxing’ the rules of DSM-5. DSM-5 25 female). Fifty three had a clinical diagnosis of Autistic

states that individuals must have impairment in all three of Disorder or Asperger Syndrome from a psychiatrist work-

the social-communication subdomains and in at least two of ing in the National Health Service who used ICD-10 crite-

the four subdomains measuring RRBs. Relaxing the rules ria for diagnosis. The remaining 18, recruited through the

in one or both of these domains (for example requiring university recruitment register, also had a clinical diagno-

only two of the three social-communication subdomains) sis based on ICD-10 criteria but had been diagnosed by a

has been found to improve sensitivity in both children (e.g. range of different clinicians. All adults received their first

Frazier et al. 2012; Mayes et al. 2013) and adults (Wilson diagnosis of autism as adults and this diagnosis was inde-

et al. 2013). pendent of the research interview. The IQs of participants

In the current study, the behavioural profile associated were not assessed; however, none were registered with

with DSM-5 criteria was explored in a group of able adults intellectual (learning) disability and all had verbal ability

first diagnosed in adulthood, many of whom completed the to self-report on their autism features in response to the

clinical interview without the presence of another inform- interview, either alone or accompanied by a family member

ant. The inclusion of both self- and other-informant assess- or friend. Thirty nine individuals were sole informants for

ments was intended to better reflect the reality of the diag- the DISCO interview; additional information was requested

nostic process for adults and address a recognised gap in the from family members for questions where the interviewee

literature (Mandy et al. 2018). Data were collected using had indicated that they did not know the answer, and was

the DSM-5 algorithm from an abbreviated version of the received in seven cases. The remaining 32 participants were

Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication Dis- accompanied by at least one other family member, spouse

orders (DISCO; Leekam et al. 2002; Wing et al. 2002), or partner, friend, social worker, foster carer, or advocate.

which includes an algorithm to guide diagnosis according The participant was always the primary interviewee, and

to DSM-5 (Carrington et al. 2014). These algorithms include generally answered all questions, unless they said they were

items from the DISCO that map onto the behavioural sub- unable to do so. The accompanying individual was always

domains described in the DSM-5 criteria, and incorporate involved for questions relating to very early development

the rules specified by DSM-5 (e.g. that an individual would and questions about early play and language, but were free

need impairment in all three social-communication sub- to add information at any point during the interview. If the

domains). By using an abbreviated form of the DISCO, it accompanying individual provided examples that the par-

was possible to focus only on those behaviours considered ticipant did not, indicating additional insight into social

most essential for the diagnosis of ASD (Carrington et al. behaviour difficulties or evidence of learned strategies for

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

5038 Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:5036–5046

example, then the accompanying individual’s testimony was intellectual disability were retained (see Fig. 3 for a full list

used. It was very rarely a matter of disagreement between of items). The threshold for each subdomain—i.e. the num-

the informants, mostly a corroboration with the addition of ber of items required to indicate the presence of the behav-

missing information or further examples. However, if there iour being measured—was then calculated following the

was a disagreement then clinical judgment and observation method used for the development of the full DISCO DSM-5

was used. algorithm, and the abbreviated algorithm was tested using

The pattern of item responses were compared with child two independent samples. Like the full 85-item algorithm,

data from which the DISCO DSM-5 algorithm (Kent et al. the reduced 54-item DSM-5 algorithm has high sensitivity

2013) had been developed. Full details of the clinical and and specificity (for details, see Carrington et al. 2014). A

demographic details of the sample can be found in previous further subset of 14 items within this reduced item set has

published reports for Sample 1 (Leekam et al. 2002; Wing been identified and published. This subset, referred to as the

et al. 2002) and Sample 2 (Maljaars et al. 2012). Only the ‘signposting set’, has been found to be particularly highly

higher ability (IQ of 70 or above) autistic child subsam- discriminating for individuals with ASD (Carrington et al.

ples were selected for the analysis, comprising 35 children 2015; Carrington et al. 2014). The ICD-10/DSM-IV-TR

(34–131 months; 30 male) with a clinical diagnosis of ICD- algorithm has also been abbreviated using the same statisti-

10 Childhood Autism or DSM-IV-TR Autistic Disorder. cal approach as for the abbreviation of the DSM-5 algorithm.

The original recruitment of samples had ethical approval The interview used in the current study (the DISCO Abbre-

from relevant regional ethics committees with the resulting viated) consisted only of items identified in the abbreviation

datasets anonymised upon study completion. Use of these of the ICD-10/DSM-IV-TR and DSM-5 DISCO algorithms;

datasets in the current analyses was approved by Cardiff Uni- this is the first study in which these items have been used as

versity’s School of Psychology Research Ethics Committee. a standalone interview.

In the DISCO—and DISCO Abbreviated—each item

Measures and Procedure is coded according to level of impairment; most items

were scored as present only if there was a ‘marked’

The Diagnostic Interview for Social and Communication (severe) impairment, although some items were marked

Disorders (DISCO; Leekam et al. 2002; Wing et al. 2002) as present when there was a ‘minor’ impairment. For the

is a 320 item semi-structured interview schedule used with DISCO Abbreviated, the algorithm settings regarding the

the parent or carer of an individual, or with the individual application of marked or minor codes for each item were not

him/herself. The interview was not developed according to a changed from their original settings for the full algorithm

specific set of diagnostic criteria; rather, its primary purpose (Kent et al. 2013; Wing et al. 2002). The DISCO includes

is to elicit information relevant to the autistic spectrum in both ‘current’ and ‘ever’ (lifetime) scores for each item.

order to assist clinicians in their judgment of an individual’s Where an item is endorsed currently it is also endorsed as

level of development, disabilities, and specific needs. Needs an ‘ever’ code. Diagnosis is typically based on ‘ever’ scores,

are assessed in the context of difficulties experienced in the reflecting the neurodevelopmental nature of the condition.

absence of structured support. The interview has good inter- The focus in the current study was, therefore, on the lifespan

rater reliability (Wing et al. 2002). It also contains diagnostic or ‘ever’ codes1, except in the few cases where DISCO pro-

algorithms to inform clinicians’ decision-making. Good cri- vided only a current scoring option (for example, non-verbal

terion validity has been found for the ICD-10/DSM-IV-TR gestures; these items are marked with # in Fig. 3). This cod-

algorithm (Leekam et al. 2002; Maljaars et al. 2012; Nygren ing method provided consistency with previous publica-

et al. 2009). Good agreement has been reported with out- tions (Carrington et al. 2015; Carrington et al. 2014; Kent

put on both the Autism Diagnostic Interview (ADI-R; Lord et al. 2013) and facilitated comparison with the equivalent

et al. 1994) and Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule published data for children (Carrington et al. 2014; Leekam

(ADOS-G; Lord et al. 2000) according to ICD-10/DSM-IV- et al. 2002).

TR criteria (Maljaars et al. 2012; Nygren et al. 2009). The

existing breadth of items included in the DISCO meant that Analysis

items could also be selected to create an algorithm for the

DSM-5 criteria, which had high sensitivity and specificity The broad profile of behaviour in children and adults was

(Kent et al. 2013). explored in line with the sub-domain and domain struc-

A reduced DSM-5 item set (54 items; Carrington et al. ture of the diagnostic criteria for DSM-5, represented by

2014) has been derived from the full algorithm set through

a process of statistical abbreviation. In brief, only items in

the full algorithm that significantly discriminated between 1

Analysis of the ‘current’ profile is presented in the supplementary

children with ASD and those with language impairment or materials

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:5036–5046 5039

Percentage (%) Percentage mee ng cut-off (%)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

A1 A1

A2 A2

A3 A3

B1 B1

B2 B2

B3 B3

B4 B4

Adults Children Adults Children

(i) (ii)

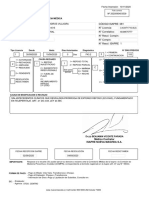

Fig. 1 i The percentage of items of the abbreviated DISCO DSM-5 developing, maintaining, and understanding social relationships, B1

algorithm marked as ever present in each subdomain for children stereotyped or repetitive motor movements, use of objects, or speech,

and adults; ii The percentage of children and adults who met the B2 insistence on sameness/inflexible routines/ritualised patterns

subdomain thresholds on the abbreviated DISCO DSM-5 algorithm. of verbal/non-verbal behaviour, B3 highly restricted, fixated interests

A1 deficits in socio-emotional reciprocity, A2 deficits in non-verbal that are abnormal in intensity or focus, B4 hyper- or hypo-reactivity

communication behaviours used for social interaction, A3 deficits in to sensory input/unusual interest in sensory aspects of environment

the DISCO algorithm (see Fig. 3 for the items in each sub- revealed a significant main effect of subdomain (children:

domain for DSM-5). First, we analysed the percentage of 2

𝜒(2) = 19.24, p < .001; adults: 𝜒(2)

2

= 73.49, p < .001). Figure 1

items endorsed within each of the subdomains and domains suggests that this effect was driven by the lower percentage

in the algorithm. Second, we analysed the percentage of of items in A2 compared with both A1 and A3. Given that

individuals meeting the total ‘cut-off’ or threshold for each five of the nine items in A2 measure current non-verbal ges-

subdomain/domain. The data for frequency of items within tures (see Fig. 3), the analyses were re-run including only

each domain/subdomain were not normally distributed (Sha- the four items where the most severe manifestations of the

piro–Wilk, p > .05), and the threshold data were categori- behaviour were coded (‘ever’ codes). When just these four

cal; consequently, Wilcoxon Signed Ranks and Friedman’s items were included for A2, the percentage of items scored

ANOVA were conducted as appropriate. Finally, the profile in this subdomain was still lower than for either of the other

of behaviours observed in adults was also examined at the social communication subdomains, and this effect was,

item-level. The percentage of individuals for whom each again, more pronounced in adults (Fig. S1). Moreover there

item was scored as ever having been present was plotted for was still a significant effect of subdomain for both children

the child and adult samples. (𝜒(2)

2

= 12.86, p = .002) and adults (𝜒(2)2

= 42.14, p < .001).

There were a number of differences between adult and Over 90% of children met the threshold in each of the A

child samples. For example only the adults were self-inform- subdomains (Fig. 1ii). For adults, however, Friedman’s

ants, while all children had parent-informants. Furthermore, ANOVA revealed a significant main effect of subdomain

the child sample included DISCO data that had initially been ( 𝜒(2)

2

= 21.35, p < .001). The subdomain in which the most

published in 2002, and represented, therefore, ‘older’ diag- participants met criterion was A1, and the subdomain with

noses. We, therefore, primarily focused on statistically ana- the fewest was A2, which is consistent with the analysis of

lysing features and subdomain scores within each sample item frequency described above.

and did not draw direct statistical comparisons. Within the RRB domain for DSM-5, the profile of behav-

iours observed for children and adults was somewhat differ-

ent (Fig. 1i and ii). For children, the subdomain with the

Results highest percentage of items was B1, relating to stereotyped

or repetitive motor mannerisms, followed by B3, highly

Subdomain and Domain Level Analysis restricted, fixated interests that are abnormal in their inten-

sity or focus. For adults, however, the subdomain with the

Within the social-communication domain for DSM-5, the highest percentage of behaviours was B2, insistence on

subdomain with the highest percentage of items endorsed, sameness, inflexible routines, or ritualised patterns of verbal

both for adults and children, was that relating to developing, or non-verbal behaviour, closely followed by B3. Although

maintaining, and understanding social relationships (A3), the profile was different for each age group, analysis by item

with the lowest percentage in the subdomain relating to non- percentage showed a significant effect of subdomain for both

verbal communication (A2; Fig. 1i). Friedman’s ANOVA

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

5040 Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:5036–5046

Percentage (%) Percentage mee ng rules (%)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

Social and communica on Social and communica on

RRBs RRBs

Adults Children Adults Children

(i) (ii)

Fig. 2 i The percentage of items within each domain marked as ever present in children and adults; ii the percentage of adults and children who

met the domain rules based on ever scores

children ( 𝜒(3)

2

= 12.51, p = .006) and adults ( 𝜒(3)2

= 26.69, in adults, particularly in the social-communication domain.

p < .001). Both age groups also had the smallest proportion Eight of the 25 social–communication items were present in

of items in the subdomain measuring hyper- or hypo-reac- 50% or more of adults. Four of these were in the subdomain

tivity to sensory stimuli (B4). relating to deficits in social emotional reciprocity, represent-

When the number of individuals meeting the subdomain ing 44% of items in that subdomain, while the remaining

threshold was considered, however, both children and adults four were in the subdomain relating to deficits in maintain-

had the lowest pass rate for B3 (restricted, fixated interests). ing and understanding relationships (57.14% of items).

For children, the pass rates in all other subdomains were Strongly endorsed social-communication behaviours in the

equally high, while for adults, the subdomain in which most adult sample included lack of awareness of others’ feelings

individuals met the threshold was B1. Friedman’s ANOVA (83.1%), does not interact with age peers (84.5%), no inter-

revealed a significant effect of subdomain only for adults est in age peers (71.8%), and lack of sharing of interests

(𝜒(3)

2

= 17.82, p < .001), probably because of the near ceiling (73.2%), which were also highly frequent in the child data-

sets (85.7%, 82.9%, 71.4%, and 82.9% respectively). Another

effect for children.

strongly endorsed behaviour in adults that was markedly less

Finally, at the domain level, both children and adults

frequent in children was ‘does not share in others’ happi-

scored on a significantly higher proportion of items in the

ness’ (73.2%; children = 22.9%). None of the items relating

social-communication (SC) domain compared with the

to non-verbal communication were observed in more than

restricted and repetitive behaviour (RRB) domain of DSM-5

50% of the adult sample, while two of the nine items in this

(Fig. 2i; children: Z = − 3.89, p < .001; adults: Z = − 2.40,

subdomain were present in 50% or more of the children.

p = .017). To meet the threshold for each domain, DSM-5

Within the RRB domain, only two items were present

specifies that all three A subdomains and at least two of the

in more than 50% of adults. These were ‘limited pattern of

four B subdomains must be met. While a high proportion of

self-chosen activities’ in B1, endorsed by 87.3% of adults

children met the threshold for both the SC (88.6%) and RRB

and 85.7% of children, and ‘collects objects’ in B3, which

domain (97.1%), 54.9% of adults failed to meet threshold

was endorsed by 56.3% of adults and just 20% of children.

on at least one of the A subdomains (Fig. 2ii). By contrast,

By contrast, in children six items across the RRB domain

94.4% of adults met threshold on at least two of the restricted

were endorsed in over 50% of the sample, including at least

and repetitive behaviour subdomains. Consistent with the

one from each subdomain.

percentage of behaviours endorsed in each domain, adults

were significantly less likely to meet the thresholds for social

communication difficulties than restricted and repetitive pat-

The Signposting Set

terns of behaviour (Z = − 5.75, p < .001).

The 14 signposting items are indicated in Fig. 3*. While ten

of these items were present in 50% or more of this sample

Item Level Analysis (Fig. 3) of high ability children, seven were also present in more

than 50% of the adult sample, indicating their diagnostic

The frequency of individual items in the DSM-5 algorithm significance for adults. Indeed, all of the particularly strong

endorsed in adults was generally lower than in children. Nev- social-communication items for adults identified above were

ertheless, there were several items with high frequencies signposting items. Six of these seven highly prevalent sign-

posting items measured social-communication behaviours,

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:5036–5046 5041

Percentage (%)

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

A1

* Sharing interests is limited or absent

Does not share in others' happiness

* No interest in age peers

* Does not seek comfort when in pain or distress

* Makes one-sided social approaches

* No emoonal response to age peers

* Does not give comfort to others

* Lack of emoonally expressive gestures

inappropriate response to others' emoons

A2

# Non-verbal communicaon is absent or odd

# Eye contact poor

lack of instrumental gestures

# Makes brief glances

* Lack of declarave gestures (joint referencing)

Lack of descripve gestures

Lack of imperave gestures

# Using other people as a mechanical aid

Does not nod or shake head

A3

* Does not interact with peers

* Lack of awareness of others' feelings

Unusual response to visitors

* Lack of friendship with age peers

Lack of pretend play

Difficult behaviour in public places

Does not understand psychological barriers

B1

* Limited paern of self-chosen acvies

* Delayed echolalia

Has complex twisng or rocking movements

Interested in abstract properes of objects

Odd tone of voice or speech

Unusual movements of hands or arms

B2

* Arranges objects in paerns

Insists on sameness in environment

Insists on sameness in rounes

Talks about repeve themes

Has unusual food fads

Acts of role of object or person repevely

B3

Collects objects

Fascinated with specific objects

Fascinaon with TV/videos

Has repeve acvies related to a specific skill

B4

Distress caused by sounds

Aimless, repeve manipulaon of objects

Unusual interest in the feel of surfaces

Indifferences to pain, heat or cold

Smells objects or people

Studies the angles of objects

Twsists hands or objects near eyes

Adult Child

Fig. 3 The percentage of adults and children for whom each DSM-5 item was ‘ever’ present. *Items in the ‘signposting’ set; #items for which

only current scores are specified by the DISCO

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

5042 Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:5036–5046

three in A1 and three from A3. The remaining ‘signposting’ interaction compared with communication, RRBs, and emo-

item present in more than 50% of adults was ‘limited pattern tional problems/maladaptive behaviour. In contrast, Shat-

of self-chosen activities’. The mean number of ‘signposting’ tuck et al. (2007) found that adults had more difficulties

items scored as ever present for the children and adults were with non-verbal communication than younger individuals.

9.06 and 7.35 respectively. Evidence of difficulties in non-verbal communication was

not replicated in the current study, both when focusing on

the most severe manifestation of behaviours (‘ever’ codes)

Discussion and when examining the current profile (see Supplementary

materials). These findings suggest that in a sample who were

Although many individuals do not receive a diagnosis of predominantly diagnosed as adults, non-verbal communica-

ASD until late adolescence or adulthood, relatively little is tion difficulties had never been as marked as difficulties with

known about the profile of individuals who are first diag- socio-emotional reciprocity and in developing and maintain-

nosed with ASD as adults. In the current study, comparison ing relationships.

of individuals diagnosed in adulthood and a sample of chil- Within the RRB domain, there was a slightly different

dren revealed that the profiles in the two groups were similar profile of behaviour in the child and adult samples. Children

overall, but with some distinctive differences. had more behaviours in the subdomains relating to repeti-

The frequency of ASD features was generally lower in tive motor movements, use of speech, or objects (B1) and

the adult sample, with the exception of a few items, such as restricted, fixated interests (B3), both compared with the

‘does not share in others’ happiness’ and ‘talks about repeti- other subdomains and in comparison with adults. Adults had

tive themes’ (Fig. 3). Those items with higher frequency in a higher percentage of behaviours in the subdomains relat-

the adult sample included behaviours less likely to be pre- ing to insistence on sameness/inflexible routines or rituals

sent in young children; for example, ‘does not share in oth- (B2) and restricted, fixated interests (B3) compared with

ers’ happiness’ is not coded in children younger than 7 years. both repetitive motor movements, use of speech, or objects

Both the adult and child samples exhibited more impair- (B1) and hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input (B4).

ments in the social-communication domain of DSM-5 com- The differing patterns of behaviour within the RRB

pared with the domain of restricted and repetitive patterns domain are consistent with known developmental changes

of behaviour (RRB). Moreover, within the social-commu- in two types of RRBs (e.g. Evans et al. 1997; Uljarević et al.

nication domain, more difficulties were reported for both 2017). Behaviours described in B2 and B3 have previously

children and adults in socio-emotional reciprocity (A1) and been described as higher-level RRBs, whilst behaviours

in deficits in developing and maintaining relationships (A3) described in B1 and B4 may be considered lower-level and

compared with non-verbal communication (A2). These more characteristic of children and lower-ability individuals

effects were more pronounced in the adult sample, and were (e.g. Prior and Macmillan 1973). Consistent with this argu-

reflected both in terms of the percentage of items and in the ment, the child sample had a higher proportion of behaviours

percentage of individuals meeting threshold (Fig. 1). The relating to stereotyped or repetitive movements (B1) than

relative lack of impairment in non-verbal communication the adult sample. Moreover, the only subdomain in which

has diagnostic significance. The DSM-5 criteria specify adults had a higher frequency of items than children was B2

impairment in all three social-communication subdomains; (insistence on sameness/inflexible routines or rituals). As

the relatively good non-verbal communication skills within such, the profile of RRBs seen in the child and adult samples

this adult sample could therefore mean that they do not are somewhat consistent with what might be expected for

qualify for a diagnosis of DSM-5 ASD. By contrast, diffi- the two age-groups.

culties in non-verbal communication are represented in two Despite these differences in the patterns of behaviour,

distinct subdomains within different domains of the ICD- the percentage of adults and children meeting the thresholds

10/DSM-IV-TR criteria; moreover, it would be possible to within each RRB subdomain (at least one behaviour present)

receive a diagnosis according to the ICD-10/DSM-IV-TR was more similar. The greatest differences between the two

criteria without demonstrating impairment in either of these samples were in B3 and B4. Although adults had a relatively

subdomains. Consequently, relatively good non-verbal com- high mean percentage of items in the subdomain relating

munication skills in these areas would be less of a barrier to to highly fixated interests (B3), this is the RRB subdomain

diagnosis according to ICD-10/DSM-IV-TR. with the highest threshold (see Fig. 1) and was, therefore,

Evidence of difficulties in social interaction relative to the subdomain in which the fewest adults met the threshold.

both communication difficulties and RRBs supports find- Moreover, despite the relatively low proportion of behav-

ings from other studies involving adults, but who were iours relating to hyper- or hypo-reactivity to sensory input

diagnosed in childhood. For example, Billstedt et al. (2007) in both groups, the percentage of adults and particularly chil-

reported a higher proportion of difficulties related to social dren who met the threshold for this subdomain was relatively

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:5036–5046 5043

high (75% for adults and 97.2% for children), indicating that for inclusion within the DISCO Abbreviated that may be

the majority of individuals had at least one sensory symp- more characteristic of individuals who do not seek diag-

tom. Although this finding is consistent with Billstedt et al. nosis until adulthood, such as more items focusing on the

(2007), the percentage of adults with at least one sensory types of RRBs that appear to be more characteristic of this

symptom was lower in the current sample (75% compared adult sample. Nevertheless, the finding of fewer non-verbal

with 93% as reported by Billstedt et al.). This finding may, communication difficulties in adults is consistent with the

again, be related to the nature of the sample, the majority of results reported by Billstedt et al. (2007), who used the non-

whom were diagnosed as adults, although this interpretation abbreviated DISCO and also included items that were not

must be viewed with caution due to the limited size of the part of the diagnostic algorithms. While further development

sample. of the DISCO Abbreviated and other interview tools will be

Given that the DSM-5 criteria require difficulty in just important in supporting the diagnosis of adults, the DSM-5

two of the four RRB subdomains, the potential implications specification that diagnosis is dependent on the presence of

of the differing RRB profiles for the child and adult samples non-verbal communication difficulties may present a barrier

for diagnosis are less striking initially than for the social for those seeking diagnosis in adulthood.

communication domain. These differences do, however, The majority of participants in the adult sample did

highlight differences in the types of RRBs that might be not bring an informant with them for the interview with

expected in individuals presenting for diagnosis as adults. the DISCO Abbreviated. Although clinical guidelines for

Rather than a focus on lower-level RRBs, these findings sug- diagnosis recommend that a detailed developmental history

gest that adults are more likely to present with difficulties should be conducted with an informant who has known

relating to a lack of flexibility in their behaviour as dem- the individual throughout their life and is able to comment

onstrated by adherence to routines and rituals, as well as on their behaviour, both currently and during childhood

fixated interests. (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2011),

Exploration of the behavioural profile at the level of indi- such informants are not always available for adults seeking

vidual items identified some key behaviours that remained a diagnosis. Where they are able to attend, their memory of

salient in the adult profile and could, therefore, be of signifi- events during the individual’s childhood may lack detail.

cance for the identification of ASD in adults. While these While these interviews can be done with the individual

were predominantly social–communication items, two addi- themselves, as they have been in the current study, they may

tional behaviours from the RRB domain were present in over lack detailed and accurate memories of their early develop-

50% of adults; these were a ‘limited pattern of self-chosen ment, or, for a subset of individuals, may not have detailed

activities’ and ‘collects objects’. Some of the strongest items insight into their own difficulties. The inclusion of both self-

in adults were part of the ‘signposting set’, a set of items and other-informant assessments in the current study was

identified as being highly discriminating for children with intended to better reflect the diagnostic process within adult

ASD relative to those with language impairment or intellec- services, and addresses a recognised gap in the literature

tual disability (Carrington et al. 2015). Although adults on (Mandy et al. 2018). Nevertheless, the limited number of

average had fewer of the behaviours described in the sign- participants within each of the two groups (with inform-

posting set than children, they still, on average, scored on ant and self-informant) prevented formal comparison of the

over half of the items, indicating that this item set may still profile of behaviour described in these different interview

have potential in signposting when referral for ASD may be approaches; however, the frequency with which items were

appropriate in adulthood. endorsed by self-informants was comparable with those who

When considering the potential implications of the find- brought an informant with them (see Fig. S5). Moreover,

ings from this study for the diagnosis of adults, it is impor- when total scores were calculated, using the algorithm, none

tant to consider whether the potential barriers to diagnosis of the overall subdomain or domain scores differed. Further

that have been identified are from the DSM-5 criteria or investigation of potential differences, including comparison

from the interview used. Although the DISCO is a compre- of self- and other-informant interviews for the same indi-

hensive interview designed to obtain a broad and detailed vidual, will enable identification of behaviours that may be

developmental history, the DISCO Abbreviated includes under- or over-reported by different informants.

only a subset of items from the full interview. While those Both the child and adult samples were diagnosed accord-

items were identified based on their predictive validity, ing to the ICD-10/DSM-IV-TR criteria. All individuals

the tool was developed and tested using a sample consist- in the child sample had a diagnosis of Autistic Disorder

ing predominantly of children. Moreover, those adults and or Childhood Autism. By contrast, the adult sample also

adolescents included in the test samples for the abbreviated included individuals with a diagnosis of Asperger Syn-

algorithm had been diagnosed in childhood or adolescence. drome. While this diagnostic discrepancy could poten-

It may, therefore, be necessary to identify further items tially account for differences observed in the behavioural

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

5044 Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:5036–5046

profiles of the two groups, it may be a genuine reflection within a more clinically feasible time frame. The findings

of the nature of these two samples. Evidence from children indicate both similarities and differences between the child

diagnosed with an ASD in the UK suggests that those with and adult profiles of ASD, with the differences highlight-

Asperger Syndrome are, on average, diagnosed later than ing potential barriers to diagnosis according to DSM-5

those with autism (Crane et al. 2016; Howlin and Asghar- criteria for higher ability adults, which may also have pre-

ian 1999). As such, a higher rate of Asperger-like presenta- vented them from being diagnosed as children. A key dif-

tions may be expected in those seeking diagnosis as adults. ference between the child and adult samples was the lower

Nevertheless, the child sample selected for the current study rate of non-verbal communication difficulties in the adult

was selected on the basis of a diagnosis of Autistic Disorder sample. This relative strength in adults could represent a

or Childhood Autism, and as such, it would be important to particular barrier to diagnosis according to the DSM-5

also draw comparisons between the adult sample, and chil- criteria that would not be as pronounced for the ICD-10/

dren who fit the ICD-10/DSM-IV-TR criteria for Asperger DSM-IV-TR criteria. In cases where a lack of impairment

Syndrome. in non-verbal communication is the only contraindication

Many adults with ASD may have learned to camouflage of an ASD diagnosis, it may be prudent, therefore, to con-

certain areas of difficulty, for example, by learning to make sider ‘relaxing’ the rules for the social-communication

eye contact during conversations and using pre-prepared domain of DSM-5 to require impairment in just two of the

social scripts. Moreover, many adults report learning to three subdomains. Furthermore, although the current study

suppress repetitive motor mannerisms, particularly whilst has found that a ‘signposting set’ of items with high pre-

interacting with others. While such techniques may have dictive validity in children also has the potential to sign-

enabled them to function more effectively within complex post diagnosis in adults, it will be important to identify

social environments—thus potentially accounting for the behaviours that are more characteristic of this population

delay in seeking support—the use of these techniques may of able individuals with ASD, who may be missed in child-

also lead to individuals under-reporting their own difficul- hood, to facilitate their diagnosis and access to support at

ties, or to others underestimating the occurrence and impact an earlier age.

of those difficulties. Social camouflaging is thought to be

more pronounced in females than males with ASD (e.g. Hull Acknowledgments The authors would like to acknowledge the con-

tributions of Dr Judith Gould, Dr Rachel Kent, Prof. Jeremy Hall, Dr

et al. 2017; Lai et al. 2017), which could, therefore, impact Helen Matthews, Prof. Dale Hay, Prof. Ina van Berckelaer-Onnes, and

on the relative rate of diagnosis for males and females. The Leiden University.

DISCO interview, however, includes questioning to check

for camouflaging and learned or rehearsed strategies. Cod- Author Contributions SJC conceived of the study, participated in its

ing is applied only with respect to what would be natural design and coordination, performed the statistical analyses, partici-

pated in the interpretation of the data, and drafted the manuscript; SB

behaviour when no strategies are in place. Self-informants participated in the design and coordination of the study, contributed

are also likely to be aware of their use of strategies to discuss to the collection of data, and participated in the interpretation of the

in the interview. This might have mitigated against finding data; US participated in the design and coordination of the study and

a gender difference in this study. While the current sample contributed to the data collection; CF participated in the design and

coordination of the study and contributed to the data collection; IN

included too few females (n = 28) to draw meaningful com- participated in the design and interpretation of the data and helped draft

parisons with males (n = 52), a growing body of research the manuscript; JM participated in the design and interpretation of the

has been focusing on the so-called ‘female profile’ of ASD. data and helped draft the manuscript; SRL conceived of the study, and

For example, it has been suggested that in young children, participated in its design and coordination, contributed to the collection

of data, participated in interpretation of the data, and helped to draft

repetitive behaviours or circumscribed interests around dolls the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

may be misinterpreted as pretend play, while older females

with ASD may exhibit apparently benign repetitive behav- Funding SB received research funding from the Economic and Social

iours, such as constantly reading a specific set of books to Research Council Wales Doctoral Training Centre (ES/J500197/1).

the detriment of social interaction (Halladay et al. 2015).

Such behaviours may be undetected, potentially contributing Compliance with Ethical Standards

to reports of lower levels of repetitive behaviours in females

than males with ASD (e.g. Mandy et al. 2012). As such, it Conflicts of interest SRL and US were members of the Stakeholder

Group for the Welsh Government’s Refreshed Strategic Action Plan

will be important to identify behaviours characteristic of for Autism. US also conducts private work for the Dyscovery Centre,

adult females with ASD to facilitate their diagnosis and sub- University of South Wales. IN holds intellectual property rights for

sequent access to appropriate support. the Dutch translation of the Diagnostic Interview for Social and Com-

The current study is the first use of an abbreviated munication Disorders.

form of the DISCO as a standalone clinical interview, and

thus represents an important step in facilitating diagnosis

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:5036–5046 5045

Ethical Approval All procedures performed in studies involving human Fountain, C., Winter, A. S., & Bearman, P. S. (2012). Six developmen-

participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the insti- tal trajectories characterize children with autism. Pediatrics, 129,

tutional research committee (Cardiff University’s School of Psychology E1112–E1120. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1601.

Research Ethics Committee: EC.14.11.11.3913RA5; Aneurin Bevan Frazier, T. W., et al. (2012). Validation of proposed DSM-5 criteria for

University Health Board: SA/453/14) and with the 1964 Helsinki Dec- autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of

laration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(1), 28–40.

Halladay, A. K., et al. (2015). Sex and gender differences in autism

Informed Consent Informed consent was obtained from all individual spectrum disorder: Summarizing evidence gaps and identifying

participants included in the study. emerging areas of priority. Molecular Autism, 6(1), 36.

Howlin, P., & Asgharian, A. (1999). The diagnosis of autism and

Asperger syndrome: Findings from a survey of 770 families.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Crea- Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 41, 834–839.

tive Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativeco Hull, L., et al. (2017). “Putting on my best normal”: Social camou-

mmons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribu- flaging in adults with autism spectrum conditions. Journal of

tion, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47, 2519–2534. https://

credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3166-5.

Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. Kent, R. G., Carrington, S. J., et al. (2013). Diagnosing autism spec-

trum disorder: Who will get a DSM-5 diagnosis? Journal of

Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 54,

1242–1250. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12085.

References Kulage, K. M., Arlene, M., Smaldone, A. M., & Cohn, E. G. (2014).

How will DSM-5 affect autism diagnosis? A systematic litera-

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical ture review and meta-analysis. Journal of autism and develop-

manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington: American Psy- mental disorders, 44(8), 1918–1932.

chiatric Association. Lai, M. C., et al. (2017). Quantifying and exploring camouflaging in

Baird, G., et al. (2006). Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum men and women with autism. Autism, 21, 690–702. https://doi.

in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the special org/10.1177/1362361316671012.

needs and autism project (SNAP). Lancet, 368(9531), 210–215. Leekam, S. R., Libby, S. J., Wing, L., Gould, J., & Taylor, C. (2002).

Baron-Cohen, S., et al. (2009). Prevalence of autism-spectrum con- The diagnostic interview for social and communication disor-

ditions: UK school-based population study. The British Jour- ders: Algorithms for ICD-10 childhood autism and Wing and

nal of Psychiatry, 194, 500–509. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp. Gould autistic spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology

bp.108.059345. and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 43, 327–342.

Billstedt, E., Gillberg, I. C., & Gillberg, C. (2007). Autism in adults: Lord, C., et al. (2000). The autism diagnostic observation schedule-

symptom patterns and early childhood predictors. Use of the generic: A standard measure of social and communication defi-

DISCO in a community sample followed from childhood. Journal cits associated with the spectrum of autism. Journal of Autism

of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 1102–1110. https://doi. and Developmental Disorders, 30, 205–223.

org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01774.x. Lord, C., Rutter, M., & Le Couteur, A. (1994). Autism diagnostic

Brugha, T. S., et al. (2011). Epidemiology of autism spectrum disor- interview-revised: A revised version of a diagnostic interview

ders in adults in the community in England. Archives of General for caregivers of individuals with possible pervasive develop-

Psychiatry, 68, 459–466. mental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disor-

Brugha, T. S., et al. (2016). Epidemiology of autism in adults across ders, 24, 659–685.

age groups and ability levels. The British Journal of Psychiatry, Maljaars, J., Noens, I., Scholte, E., & van Berckelaer-Onnes, I.

209, 498–503. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.174649. (2012). Evaluation of the criterion and convergent validity of

Carrington, S. J., et al. (2015). Signposting for diagnosis of autism the diagnostic interview for social and communication disorders

spectrum disorder using the diagnostic interview for social and in young and low-functioning children. Autism, 16(5), 487–497.

communication disorders (DISCO). Research in Autism Spectrum Mandy, W., et al. (2018). Assessing autism in adults: An evaluation

Disorders, 9, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.10.003. of the developmental, dimensional and diagnostic interview-

Carrington, S. J., Kent, R. G., et al. (2014). DSM-5 autism spec- adult version (3Di-adult). Journal of Autism and Develop-

trum disorder: In search of essential behaviours for diagnosis. mental Disorders, 48, 549–560. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1080

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8, 701–715. https://doi. 3-017-3321-z.

org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.03.017. Mandy, W., Chilvers, R., Chowdhury, U., Salter, G., Seigal, A., &

Charman, T., et al. (2017). The EU-AIMS Longitudinal European Skuse, D. (2012). Sex differences in autism spectrum disorder:

Autism Project (LEAP): Clinical characterisation. Molecular Evidence from a large sample of children and adolescents. Journal

Autism, 8(1), 27. of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 42, 1304–1313. https://

Crane, L., Chester, J. W., Goddard, L., Henry, L. A., & Hill, E. L. doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1356-0.

(2016). Experiences of autism diagnosis: A survey of over 1000 Mayes, S. D., Black, A., & Tierney, C. D. (2013). DSM-5 under-

parents in the United Kingdom. Autism, 20, 153–162. https://doi. identifies PDDNOS: Diagnostic agreement between the DSM-5,

org/10.1177/1362361315573636. DSM-IV, and checklist for autism spectrum disorder. Research in

Evans, D. W., et al. (1997). Ritual, habit, and perfectionism: The preva- Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7, 298–306.

lence and development of compulsive-like behavior in normal McGovern, C. W., & Sigman, M. (2005). Continuity and change from

young children. Child Development, 68, 58–68. early childhood to adolescence in autism. Journal of Child Psy-

Fecteau, S., Mottron, L., Berthiaume, C., & Burack, J. A. (2003). chology and Psychiatry, 46, 401–408. https://doi.org/10.111

Developmental changes of autistic symptoms. Autism, 7, 255–268. 1/j.1469-7610.2004.00361.x.

McPartland, J. C., Reichow, B., & Volkmar, F. R. (2012). Sensitivity

and specificity of proposed DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for autism

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

5046 Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (2019) 49:5036–5046

spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and of preschool children with autism spectrum disorder. JAMA

Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(4), 368–383. Psychiatry, 72, 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychi

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2011). Autism atry.2014.2463.

diagnosis in children and young people: Recognition, referral Taheri, A., & Perry, A. (2012). Exploring the proposed DSM-5 criteria

and diagnosis of children and young people on the autism spec- in a clinical sample. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disor-

trum. CG128. London: National Institute for Health and Care ders, 42, 1810–1817. https: //doi.org/10.1007/s10803 -012-1599-4.

Excellence. Uljarević, M., et al. (2017). Development of restricted and repetitive

Nygren, G., Hagberg, B., Billstedt, E., Skoglund, A., Gillberg, C., & behaviors from 15 to 77 months: Stability of two distinct sub-

Johansson, M. (2009). The swedish version of the diagnostic inter- types? Developmental Psychology, 53, 1859–1868. https://doi.

view for social and communication disorders (DISCO-10). Psy- org/10.1037/dev0000324.

chometric properties. Journal of Autism and Developmental Dis- Wilson, C. E., et al. (2013). Comparison of ICD-10R, DSM-IV-TR and

orders, 39, 730–741. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-008-0678-z. DSM-5 in an adult autism spectrum disorder diagnostic clinic.

Prior, M., & Macmillan, M. B. (1973). Maintenance of sameness in Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 2515–2525.

children with Kanners syndrome. Journal of Autism and Child- Wing, L., Leekam, S. R., Libby, S. J., Gould, J., & Larcombe, M.

hood Schizophrenia, 3, 154–167. (2002). The diagnostic interview for social and communication

Seltzer, M. M., Shattuck, P., Abbeduto, L., & Greenberg, J. S. (2004). disorders: Background, inter-rater reliability and clinical use.

Trajectory of development in adolescents and adults with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disci-

Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research plines, 43, 307–325.

Reviews, 10, 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.20038.

Shattuck, P. T., et al. (2007). Change in autism symptoms and maladap- Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to

tive behaviors in adolescents and adults with an autism spectrum jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37,

1735–1747. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0307-7.

Szatmari, P., et al. (2015). Developmental trajectories of symp-

tom severity and adaptive functioning in an inception cohort

13

Content courtesy of Springer Nature, terms of use apply. Rights reserved.

Terms and Conditions

Springer Nature journal content, brought to you courtesy of Springer Nature Customer Service Center GmbH (“Springer Nature”).

Springer Nature supports a reasonable amount of sharing of research papers by authors, subscribers and authorised users (“Users”), for small-

scale personal, non-commercial use provided that all copyright, trade and service marks and other proprietary notices are maintained. By

accessing, sharing, receiving or otherwise using the Springer Nature journal content you agree to these terms of use (“Terms”). For these

purposes, Springer Nature considers academic use (by researchers and students) to be non-commercial.

These Terms are supplementary and will apply in addition to any applicable website terms and conditions, a relevant site licence or a personal

subscription. These Terms will prevail over any conflict or ambiguity with regards to the relevant terms, a site licence or a personal subscription

(to the extent of the conflict or ambiguity only). For Creative Commons-licensed articles, the terms of the Creative Commons license used will

apply.

We collect and use personal data to provide access to the Springer Nature journal content. We may also use these personal data internally within

ResearchGate and Springer Nature and as agreed share it, in an anonymised way, for purposes of tracking, analysis and reporting. We will not

otherwise disclose your personal data outside the ResearchGate or the Springer Nature group of companies unless we have your permission as

detailed in the Privacy Policy.

While Users may use the Springer Nature journal content for small scale, personal non-commercial use, it is important to note that Users may

not:

1. use such content for the purpose of providing other users with access on a regular or large scale basis or as a means to circumvent access

control;

2. use such content where to do so would be considered a criminal or statutory offence in any jurisdiction, or gives rise to civil liability, or is

otherwise unlawful;

3. falsely or misleadingly imply or suggest endorsement, approval , sponsorship, or association unless explicitly agreed to by Springer Nature in

writing;

4. use bots or other automated methods to access the content or redirect messages

5. override any security feature or exclusionary protocol; or

6. share the content in order to create substitute for Springer Nature products or services or a systematic database of Springer Nature journal

content.

In line with the restriction against commercial use, Springer Nature does not permit the creation of a product or service that creates revenue,

royalties, rent or income from our content or its inclusion as part of a paid for service or for other commercial gain. Springer Nature journal

content cannot be used for inter-library loans and librarians may not upload Springer Nature journal content on a large scale into their, or any

other, institutional repository.

These terms of use are reviewed regularly and may be amended at any time. Springer Nature is not obligated to publish any information or

content on this website and may remove it or features or functionality at our sole discretion, at any time with or without notice. Springer Nature

may revoke this licence to you at any time and remove access to any copies of the Springer Nature journal content which have been saved.

To the fullest extent permitted by law, Springer Nature makes no warranties, representations or guarantees to Users, either express or implied

with respect to the Springer nature journal content and all parties disclaim and waive any implied warranties or warranties imposed by law,

including merchantability or fitness for any particular purpose.

Please note that these rights do not automatically extend to content, data or other material published by Springer Nature that may be licensed

from third parties.

If you would like to use or distribute our Springer Nature journal content to a wider audience or on a regular basis or in any other manner not

expressly permitted by these Terms, please contact Springer Nature at

onlineservice@springernature.com

You might also like

- Parts Therapy Quick Reference PDFDocument2 pagesParts Therapy Quick Reference PDFdamcz67% (3)

- Barbaro & Dissanayake (2010) - SACS PDF FINAL PDFDocument10 pagesBarbaro & Dissanayake (2010) - SACS PDF FINAL PDFAnonymous 75M6uB3Ow100% (1)

- ESDMDocument9 pagesESDMVictória NamurNo ratings yet

- Pisula Et AlDocument42 pagesPisula Et AlAnonymous 75M6uB3OwNo ratings yet

- Efects of Diagnostic Severity upon Sex DiferencesDocument12 pagesEfects of Diagnostic Severity upon Sex DiferencesAmyNo ratings yet

- AutismoDocument8 pagesAutismoSol ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Hearing Impairment and ASD in Infants and ToddlersDocument13 pagesHearing Impairment and ASD in Infants and ToddlersIsabella MontalvãoNo ratings yet

- Demographic and cognitive profile of adults seeking autism diagnosisDocument32 pagesDemographic and cognitive profile of adults seeking autism diagnosisLD Kabinet Dnevni BoravakNo ratings yet

- Gender Dysphoria and Co-Occurring Autism Spectrum Disorders: Review, Case Examples, and Treatment ConsiderationsDocument7 pagesGender Dysphoria and Co-Occurring Autism Spectrum Disorders: Review, Case Examples, and Treatment ConsiderationsMilo DueNo ratings yet

- The Childhood Autism Spectrum Test (CAST) :spanish Adaptation and ValidationDocument8 pagesThe Childhood Autism Spectrum Test (CAST) :spanish Adaptation and ValidationJose Alonso Aguilar ValeraNo ratings yet

- Autism Spectrum Disorder An Emerging Opportunity.5Document7 pagesAutism Spectrum Disorder An Emerging Opportunity.5b-djoeNo ratings yet

- Kanne Gerber Et Al Vineland 2010Document12 pagesKanne Gerber Et Al Vineland 2010Gh8jfyjnNo ratings yet

- Article Psicometria PDFDocument14 pagesArticle Psicometria PDFEstela RecueroNo ratings yet

- Autism in Adolescents and Adults MesibovDocument23 pagesAutism in Adolescents and Adults MesibovSmurfing is FunNo ratings yet

- Computational Methods To Measure Patterns of GazeDocument14 pagesComputational Methods To Measure Patterns of GazeDaniel NovakNo ratings yet

- Wiggins 2019Document9 pagesWiggins 2019tania luarteNo ratings yet

- Literature Review by Shahir Samad Social ImpairmentDocument3 pagesLiterature Review by Shahir Samad Social ImpairmentirfanzukriNo ratings yet

- Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorders OutcomesDocument9 pagesAdults With Autism Spectrum Disorders OutcomesAnaLaura JulcahuancaNo ratings yet

- Visual attention to social and non-social objects across the autism spectrumFrom EverandVisual attention to social and non-social objects across the autism spectrumNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersFrom EverandDiagnosis and Treatment of Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Autism Research - 2021 - Tan - Prevalence and Age of Onset of Regression in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder ADocument17 pagesAutism Research - 2021 - Tan - Prevalence and Age of Onset of Regression in Children With Autism Spectrum Disorder AAlhabbadNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Early DiagnoDocument11 pagesThe Importance of Early Diagnoiuliabucur92No ratings yet

- Comorbid Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents With Attention-Deficit:hyperactivity Disorder in A Large Nationwide StudyDocument12 pagesComorbid Mental Disorders in Children and Adolescents With Attention-Deficit:hyperactivity Disorder in A Large Nationwide StudyMarina HeinenNo ratings yet

- Gender Difference in The Association Between Executive Function and Autistic Traits in Typically Developing ChildrenDocument11 pagesGender Difference in The Association Between Executive Function and Autistic Traits in Typically Developing ChildrenJosé MonroyNo ratings yet

- Young's Schema Questionnaire - Short Form Version 3 (YSQ-S3) : Preliminary Validation in Older AdultsDocument35 pagesYoung's Schema Questionnaire - Short Form Version 3 (YSQ-S3) : Preliminary Validation in Older AdultsFiona DayNo ratings yet

- The EU-AIMS Longitudinal European Autism Project (LEAP) : Clinical CharacterisationDocument21 pagesThe EU-AIMS Longitudinal European Autism Project (LEAP) : Clinical CharacterisationceliaNo ratings yet

- BookChapter MethodsOfScreeningForCoreSymptDocument18 pagesBookChapter MethodsOfScreeningForCoreSymptXavier TorresNo ratings yet

- A Qualitative Exploration of The Female Experience of AutismDocument14 pagesA Qualitative Exploration of The Female Experience of AutismBárbaraLaureanoNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Tutor: Itinerant Teacher 1999Document190 pagesEarly Childhood Tutor: Itinerant Teacher 1999MultazamNo ratings yet

- Braithwaite - 2020 - Chapter 13 - Social Attentionchapter 13 - Social AttentionDocument33 pagesBraithwaite - 2020 - Chapter 13 - Social Attentionchapter 13 - Social AttentionRobert WardNo ratings yet

- Sex Differences in Predicting ADHD Clinical Diagnosis and Pharmacological TreatmentDocument9 pagesSex Differences in Predicting ADHD Clinical Diagnosis and Pharmacological TreatmentLiesth YaninaNo ratings yet

- Early Motor Diferences in Infants at Elevated Likelihood of AutismDocument19 pagesEarly Motor Diferences in Infants at Elevated Likelihood of AutismIngrid DíazNo ratings yet

- Autism and Pervasive Developmental DisordersDocument38 pagesAutism and Pervasive Developmental DisordersSumita KunalingamNo ratings yet

- Journal of Communication Disorders: Rachel Preston, Marie Halpin, Gemma Clarke, Sharon MillardDocument14 pagesJournal of Communication Disorders: Rachel Preston, Marie Halpin, Gemma Clarke, Sharon MillardNUR SYIFAA HAZWANI MOHAMAD SUHAIMINo ratings yet

- CBCL Profiles of Children and Adolescents With Asperger Syndrome - A Review and Pilot StudyDocument12 pagesCBCL Profiles of Children and Adolescents With Asperger Syndrome - A Review and Pilot StudyWildan AnrianNo ratings yet

- Adult Asperger Syndrome and The Utility of Cognitive PotrivitDocument14 pagesAdult Asperger Syndrome and The Utility of Cognitive Potrivitmadytzaingeras061No ratings yet

- Romantic relationships and satisfaction among adults with autismDocument13 pagesRomantic relationships and satisfaction among adults with autismmavikNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Spen 2020 100831Document17 pages10 1016@j Spen 2020 100831tania luarteNo ratings yet

- Journal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders: A 1 A 1 B A 1Document7 pagesJournal of Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders: A 1 A 1 B A 1cutkilerNo ratings yet

- Autism in Transition From High School To College: Scholarworks@UarkDocument29 pagesAutism in Transition From High School To College: Scholarworks@UarkBernard CarpioNo ratings yet

- Adult PsychiatricDocument21 pagesAdult PsychiatricAndré SilvaNo ratings yet

- Sex Differences in Autism Spectrum Disorders Across The LifespanDocument10 pagesSex Differences in Autism Spectrum Disorders Across The LifespanBárbaraLaureanoNo ratings yet

- Hus Et Al., 2014 - Module 4 Algorithm and Comparison ScoresDocument18 pagesHus Et Al., 2014 - Module 4 Algorithm and Comparison ScoresSafeSleep BrookdaleNo ratings yet

- Chapter 02 Literature ReviewDocument20 pagesChapter 02 Literature ReviewAyesha ArshedNo ratings yet

- Behavioral, Cognitive, and Adaptive Development in Infants With Autism Spectrum Disorder in The First 2 Years of LifeDocument10 pagesBehavioral, Cognitive, and Adaptive Development in Infants With Autism Spectrum Disorder in The First 2 Years of LifeJose Alonso Aguilar ValeraNo ratings yet

- Ncbi - Nlm.nih - Gov-Autism Spectrum Disorder The Impact of Stressful and Traumatic Life Events and Implications For CliniDocument13 pagesNcbi - Nlm.nih - Gov-Autism Spectrum Disorder The Impact of Stressful and Traumatic Life Events and Implications For CliniJinny DavisNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AutismeDocument11 pagesJurnal AutismeKabhithra ThiayagarajanNo ratings yet

- Developmental Profiles SchizotipyDocument23 pagesDevelopmental Profiles SchizotipyDavid MastrangeloNo ratings yet

- PDD-NOS Diagnostic ChallengesDocument16 pagesPDD-NOS Diagnostic ChallengesTracey RompasNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Tourette Syndrome and Chronic Tics I PDFDocument16 pagesPrevalence of Tourette Syndrome and Chronic Tics I PDFFitriazneNo ratings yet

- Practice Parameter For The Assessment andDocument21 pagesPractice Parameter For The Assessment andBianca curveloNo ratings yet

- Pone 0080247Document9 pagesPone 0080247Kurumeti Naga Surya Lakshmana KumarNo ratings yet

- REINO UNIDO Brett2016 Article FactorsAffectingAgeAtASDDiagno PDFDocument11 pagesREINO UNIDO Brett2016 Article FactorsAffectingAgeAtASDDiagno PDFKarel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- A Literature Analysis On The Quality of Life in Adults With AutismDocument11 pagesA Literature Analysis On The Quality of Life in Adults With AutismPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Autism Annotated Bibliography - EditedDocument10 pagesAutism Annotated Bibliography - EditedGerald MboyaNo ratings yet

- Second Grade - A First Semester GBD Module: Amer - Nezar1800a@comed - Uobaghdad.edu - IqDocument15 pagesSecond Grade - A First Semester GBD Module: Amer - Nezar1800a@comed - Uobaghdad.edu - IqNazar FadhilNo ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka Proforma For Registration For Subject For DissertationDocument20 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, Karnataka Proforma For Registration For Subject For DissertationAsha JiluNo ratings yet

- 2020 Article 4810Document21 pages2020 Article 4810Silvia LascarezNo ratings yet

- CBCL Accuracy for ASD Screening Impacted by Emotional Behavioral ProblemsDocument10 pagesCBCL Accuracy for ASD Screening Impacted by Emotional Behavioral ProblemsCristinaNo ratings yet

- Early Detection of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Screening Between 12 and 24 Months of AgeDocument10 pagesEarly Detection of Autism Spectrum Disorders: Screening Between 12 and 24 Months of AgeJose Alonso Aguilar ValeraNo ratings yet

- Brainsci 12 01427 v2Document14 pagesBrainsci 12 01427 v2Marsa Nabil HawariNo ratings yet

- Genetic Evidence of Gender Difference in AutismDocument10 pagesGenetic Evidence of Gender Difference in AutismLeonardo Adolpho MartinsNo ratings yet

- The Female Protective Effect in Autism SDocument10 pagesThe Female Protective Effect in Autism SNps Caren RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Friendship Qualities ScaleDocument4 pagesFriendship Qualities ScalevcuadrosvNo ratings yet

- ASD in Females Are We Overstating The GenderDocument18 pagesASD in Females Are We Overstating The GendervcuadrosvNo ratings yet

- Enhanced Milieu Teaching: Effects of Parent-Implemented Language InterventionDocument21 pagesEnhanced Milieu Teaching: Effects of Parent-Implemented Language InterventionvcuadrosvNo ratings yet

- Behavior Predictors of Language Development Over 2 Years in Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument15 pagesBehavior Predictors of Language Development Over 2 Years in Children With Autism Spectrum DisordersvcuadrosvNo ratings yet

- Charlop Christy2000Document16 pagesCharlop Christy2000vcuadrosvNo ratings yet

- Promising Innovations in AAC For Individuals With Autism Spectrum DisordersDocument2 pagesPromising Innovations in AAC For Individuals With Autism Spectrum DisordersvcuadrosvNo ratings yet

- AAC and Autism: Compelling Issues, Promising Practices and Future DirectionsDocument4 pagesAAC and Autism: Compelling Issues, Promising Practices and Future DirectionsvcuadrosvNo ratings yet

- dooh &RPXQD 1Rpeuh$Iloldgr 1 /LFHQFLD 1 &ruuhodwlyr 1 5Hvro&Rpslq 1 &RPSLQ 1 5HVRO, 6$35 (&Ï', 2,6$35 (Document1 pagedooh &RPXQD 1Rpeuh$Iloldgr 1 /LFHQFLD 1 &ruuhodwlyr 1 5Hvro&Rpslq 1 &RPSLQ 1 5HVRO, 6$35 (&Ï', 2,6$35 (vcuadrosvNo ratings yet

- TelepathyDocument6 pagesTelepathyAngela Carel Jumawan100% (2)

- Distance Learning TheoryDocument18 pagesDistance Learning TheoryMaryroseNo ratings yet

- Lucid Dreams - LISTENINGDocument3 pagesLucid Dreams - LISTENINGFernanda SalesNo ratings yet

- SOWPIF Unit 2 The Components of CaseworkDocument13 pagesSOWPIF Unit 2 The Components of CaseworkChrismel Ray TabujaraNo ratings yet

- Perdev: Quarter 1Document13 pagesPerdev: Quarter 1Monica De GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Art Therapy With Orphaned Children: Dynamics of Early Relational Trauma and Repetition CompulsionDocument11 pagesArt Therapy With Orphaned Children: Dynamics of Early Relational Trauma and Repetition CompulsionGabriella SalzNo ratings yet

- Career Interest ProfilerDocument2 pagesCareer Interest Profilerapi-478649784No ratings yet

- Canadian Scene Study Assignment 3mip 2014Document2 pagesCanadian Scene Study Assignment 3mip 2014api-202765737No ratings yet

- Neuropsychological Assessment and RehabilitationDocument222 pagesNeuropsychological Assessment and RehabilitationReza Najafi100% (1)

- Dad Gets Post Natal Depression TooDocument3 pagesDad Gets Post Natal Depression TooAndan SariNo ratings yet

- IPCR Form: Individual Performance Commitment and ReviewDocument6 pagesIPCR Form: Individual Performance Commitment and ReviewBadong AhillonNo ratings yet

- Domains of LearningDocument8 pagesDomains of Learningapi-644127469No ratings yet

- McDonalds BrandDocument13 pagesMcDonalds BrandravisittuNo ratings yet

- ABCS Scale - Instructions 11.18 PDFDocument2 pagesABCS Scale - Instructions 11.18 PDFAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- Building the psyche of an opera singerDocument1 pageBuilding the psyche of an opera singerIrina MarinaşNo ratings yet

- A. Training For The Pathways Orientation For The Youth - (June 13, 2022)Document1 pageA. Training For The Pathways Orientation For The Youth - (June 13, 2022)Min AshtrielleNo ratings yet

- DR oDocument26 pagesDR oapi-247961469100% (1)

- Functions of The FamilyDocument10 pagesFunctions of The FamilyMrBinet100% (4)

- Meaning and Significance of PerceptionDocument18 pagesMeaning and Significance of Perceptionagisj877742No ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Family Counseling in Developing Self-Care Skills for Autistic ChildrenDocument81 pagesThe Effectiveness of Family Counseling in Developing Self-Care Skills for Autistic ChildrenMajid MaghribiNo ratings yet

- Workplace Boundaries Pda OutlineDocument3 pagesWorkplace Boundaries Pda Outlineapi-280070611No ratings yet

- BTS guidance on driving and sleep apnoeaDocument3 pagesBTS guidance on driving and sleep apnoeaIndira DeviNo ratings yet

- Structural Models of AttitudesDocument8 pagesStructural Models of AttitudesRandika Fernando100% (1)

- PE04 Module 1.1 Fundamentals of Group DynamicsDocument8 pagesPE04 Module 1.1 Fundamentals of Group DynamicsRG MendozaNo ratings yet

- Sociological Perspectives and RolesDocument9 pagesSociological Perspectives and RolesAriane CiprianoNo ratings yet

- PSY 124 Course Outline ScheduleDocument3 pagesPSY 124 Course Outline ScheduleLexy AnnNo ratings yet

- Topic 5 at 6Document5 pagesTopic 5 at 6Relyn Luriban Perucho-MartinezNo ratings yet

- AMA EDUCATION - PHYSICAL SELFDocument11 pagesAMA EDUCATION - PHYSICAL SELFJoseph BaysaNo ratings yet

- Ecr RDocument13 pagesEcr Rmihaela neacsuNo ratings yet