Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Transboundary 6

Uploaded by

Patricia Ann T. AlingodOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Transboundary 6

Uploaded by

Patricia Ann T. AlingodCopyright:

Available Formats

administrator the law is the foundation upon which an implementation strategy is hung.

One of the sources of conflict in

American-style governments is this disconnect between administrators and legislators. This is not to deny the

considerable overlap between the two branches in policy making, but it does reflect a mind-set about policy making. A

well-conceived and widely supported law nevertheless may be difficult to implement. The legislator (and chief executive)

seeks to achieve success through a political decision process in which consensus is a tool. Administrators often turn to

more rational analytic methods. As was discussed in the chapter on policy analysis the “best” outcome derived from

rational analysis may not be politically feasible. As managers advance within the organization they find that the problem

to be solved is as much one of political feasibility as it is technical assessment. One of the most difficult transitions for

public service professionals is the shift from a program and process focus to a policy-making political focus.

Managing at the Margin

Each of the different types of transboundary relationships calls for a different management outlook, because the context

and environment of each is different. The internal demands of the field office-central office are interesting because the

dispute is between persons who presume that they have the same goal and outlook because they work within the same

organization. Yet the management lesson concerns communications and perspective. The assumption that “we have the

same goals” is at least partly wrong. The easy assumption that everyone knows what and why things are done is also

wrong. Open communication even about what is assumed to be obvious is necessary because the uses of information

are different and, therefore, the form and shape of information transfer is different. In this sense, managing in a peer-to-

peer relationship is more straightforward, even though it involves persons in other agencies and jurisdictions. Typically,

peer-to-peer relationships are voluntary, but also driven by a shared professional ethos. Managing such relationships are

as much about time management as anything. The single caveat is that certain regions and areas have different histories

with such relationships. In areas where such relationships have been unsuccessful, a manager may encounter resistance

from other jurisdictions or from political leadership in the community.

Intergovernmental relations often have the characteristics of peer-to-peer relationship, particularly in the technical silos

of special districts, but because they are both horizontal and vertical they are more complicated. Depending on the

policy type being implemented, such relations may have some of the characteristics of the field office-central office

dynamic. Also because of the political dimension to vertical relationships, there may be an antagonistic rather than

cooperative history in the relationship. In addition, this type of relationship reflects the complex political relationships

and history of government jurisdictions. Creating regional governance organizations is the most difficult of all

intergovernmental relationships.

Politics infuses the transboundary process more than may first be apparent. This is not so much a problem as it is a

warning to recognize that the rules of the game in the relationship are often far removed from simple, technical,

professional exchanges. Mastering the dynamic interplay of politics may be the most critical for the manager navigating

the boundary.

You might also like

- The Politics of Public Higher Education: Strategic Decisions Forged From Constituency Competition, Cooperation, and CompromiseFrom EverandThe Politics of Public Higher Education: Strategic Decisions Forged From Constituency Competition, Cooperation, and CompromiseNo ratings yet

- Navigating Through Turbulent Times: Applying a System and University Strategic Decision Making ModelFrom EverandNavigating Through Turbulent Times: Applying a System and University Strategic Decision Making ModelNo ratings yet

- Transboundary 1Document1 pageTransboundary 1Patricia Ann T. AlingodNo ratings yet

- Transboundary 3Document1 pageTransboundary 3Patricia Ann T. AlingodNo ratings yet

- Transboundary 5Document1 pageTransboundary 5Patricia Ann T. AlingodNo ratings yet

- Doctoral Program DescriptionDocument7 pagesDoctoral Program DescriptionRelazioni Internazionali DEMSNo ratings yet

- Doctoral Program DescriptionDocument6 pagesDoctoral Program DescriptionhfredianNo ratings yet

- GovernanceAdvancing The Paradigm (Jacob Torfing, B. Guy Peters, Jon Pierre Etc.)Document284 pagesGovernanceAdvancing The Paradigm (Jacob Torfing, B. Guy Peters, Jon Pierre Etc.)suresh pantNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument8 pagesUntitledLeo Andrei BarredoNo ratings yet

- Governmental PoliticsDocument15 pagesGovernmental PoliticsCleon Magayanes100% (1)

- A State-Level Examination of Bureaucratic Policymaking: The Internal Organization of Attention - Jessica TermanDocument4 pagesA State-Level Examination of Bureaucratic Policymaking: The Internal Organization of Attention - Jessica TermanDhonna MacatangayNo ratings yet

- Reading 3Document4 pagesReading 3Mary joy VinluanNo ratings yet

- Politics and Public Sector.Document14 pagesPolitics and Public Sector.Atisha RamsurrunNo ratings yet

- Federalism 2016 02Document14 pagesFederalism 2016 02Bhawani ShankerNo ratings yet

- 8703-Article Text-17063-1-10-20210528Document14 pages8703-Article Text-17063-1-10-20210528자기여보No ratings yet

- GPO Box 935 Bhat Bhateni, Kathmandu 441-8345/444-3316Document39 pagesGPO Box 935 Bhat Bhateni, Kathmandu 441-8345/444-3316Richa ShahiNo ratings yet

- PA 201 Assignment 1Document4 pagesPA 201 Assignment 1Labonno RahmanNo ratings yet

- Intrface and DichotomyDocument17 pagesIntrface and DichotomyingridNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics Comparative PoliticsDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics Comparative Politicsafeascdcz100% (1)

- BookCover AliFarazmand-mergedDocument10 pagesBookCover AliFarazmand-mergedBasyir ashrafNo ratings yet

- PA Chapter 4 and 5-PADM-201Document16 pagesPA Chapter 4 and 5-PADM-201wubeNo ratings yet

- Strategic Managemment Perry Ring AMR Apr 1985Document12 pagesStrategic Managemment Perry Ring AMR Apr 1985Anderson De Oliveira ReisNo ratings yet

- English Grammer 2Document15 pagesEnglish Grammer 2Zainab AbbasNo ratings yet

- The Politics-Bureaucracy Interface in Developing Countries: N.dasandi@bham - Ac.ukDocument41 pagesThe Politics-Bureaucracy Interface in Developing Countries: N.dasandi@bham - Ac.ukmuhammad izzudin haqNo ratings yet

- Concept of Political DevelopmentDocument2 pagesConcept of Political DevelopmentNorhanodin M. SalicNo ratings yet

- Comparative Politics Thesis TopicsDocument4 pagesComparative Politics Thesis Topicswcldtexff100% (2)

- The Politics of Bureaucracy A Continuing SagaDocument8 pagesThe Politics of Bureaucracy A Continuing SagaJunior GuedesNo ratings yet

- Week 3 - May & JochimDocument2 pagesWeek 3 - May & JochimLucia GuaitaNo ratings yet

- The Proposal Must Contain A Preliminary Presentation of The Scientific Approach, Theoretical Foundation, Methodological Approach and Progression PlanDocument9 pagesThe Proposal Must Contain A Preliminary Presentation of The Scientific Approach, Theoretical Foundation, Methodological Approach and Progression PlanBest JohnNo ratings yet

- Governance: Public Management Models Razvan Manta Paper 4 Alexandra-Oana BurlanDocument3 pagesGovernance: Public Management Models Razvan Manta Paper 4 Alexandra-Oana BurlanRazvan Manta100% (1)

- Role of Inter-Governmental Relations in Policy-MakingDocument16 pagesRole of Inter-Governmental Relations in Policy-MakingmobiuserdedNo ratings yet

- Devolution and DecentralizationDocument10 pagesDevolution and DecentralizationkofiadrakiNo ratings yet

- XamdaDocument13 pagesXamdacankawaabNo ratings yet

- Policy Implementation BangladeshDocument18 pagesPolicy Implementation Bangladeshntv2000No ratings yet

- Think Tanks in Post-Conflict Contexts: Towards Evidence-Informed Governance ReformsDocument34 pagesThink Tanks in Post-Conflict Contexts: Towards Evidence-Informed Governance ReformsArnaldo PelliniNo ratings yet

- Hagen How Interagency Coordination Is Affected by Agency Policy AutonomyDocument26 pagesHagen How Interagency Coordination Is Affected by Agency Policy AutonomyLúbar Andrés Chaparro CabraNo ratings yet

- The Implementation of Decentralization: A Case Study of District Planning in Agra District, Uttar Pradesh, IndiaDocument15 pagesThe Implementation of Decentralization: A Case Study of District Planning in Agra District, Uttar Pradesh, IndiaAnonymous BqTt5TdDS100% (1)

- 03 RSD Prachi Khalil Agricultural PolicyDocument34 pages03 RSD Prachi Khalil Agricultural PolicyR S DeshpandeNo ratings yet

- Dimensions of Governance For The Public SectorDocument29 pagesDimensions of Governance For The Public SectorThanh Tu NguyenNo ratings yet

- Political Science DocumentDocument23 pagesPolitical Science DocumentJohn SmithNo ratings yet

- Democratic Regimes and Cabinet Politics: A Global PerspectiveDocument14 pagesDemocratic Regimes and Cabinet Politics: A Global PerspectiveSilvio CastroNo ratings yet

- Koop Lodge CoordinationDocument20 pagesKoop Lodge CoordinationLúbar Andrés Chaparro CabraNo ratings yet

- 2005 - Jurnal - Q - PNA - Policy Networks and Good Governance - A DiscussionDocument12 pages2005 - Jurnal - Q - PNA - Policy Networks and Good Governance - A Discussionwijoyo.adi89No ratings yet

- Assignment in Public AdmiistrationDocument6 pagesAssignment in Public AdmiistrationJline TeodosioNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic and Corporate Networks Bridges To Foreign LocationsDocument25 pagesDiplomatic and Corporate Networks Bridges To Foreign LocationsYassine MerizakNo ratings yet

- KonklusiDocument52 pagesKonklusidonita rahmyNo ratings yet

- Comparative Public AdministrationDocument26 pagesComparative Public Administrationashish19810% (1)

- IBNMODULE1Document14 pagesIBNMODULE1divyaNo ratings yet

- Background: The Politics-Administration Dichotomy: An Empirical Search For Correspondence Between Theory and PracticeDocument3 pagesBackground: The Politics-Administration Dichotomy: An Empirical Search For Correspondence Between Theory and PracticeBerhane WeldegebrielNo ratings yet

- Form of GovernmentDocument22 pagesForm of GovernmentTiffany KomichoNo ratings yet

- Government Governance (GG) and Inter-Ministerial Policy Coordination (IMPC) in Eastern and Central Europe and Central AsiaDocument18 pagesGovernment Governance (GG) and Inter-Ministerial Policy Coordination (IMPC) in Eastern and Central Europe and Central AsiacsendinfNo ratings yet

- Is There A Philippine Public Administration?: Raul P. de GuzmanDocument8 pagesIs There A Philippine Public Administration?: Raul P. de GuzmanNathaniel Miranda Dagsa JrNo ratings yet

- Chapter Review (For Article Review Project) : - Year of PublicationDocument3 pagesChapter Review (For Article Review Project) : - Year of Publicationmr QNo ratings yet

- Peters FDocument18 pagesPeters Ferocamx3388No ratings yet

- Governance - Public Policy - BritannicaDocument4 pagesGovernance - Public Policy - BritannicaMuhammad IbrarNo ratings yet

- Current Portions Will Remain Important in Revised UPSC PatternDocument7 pagesCurrent Portions Will Remain Important in Revised UPSC PatternInvincible BaluNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Management and Development: The Role of BureaucracyDocument20 pagesHuman Resource Management and Development: The Role of BureaucracyCelestialMirandaNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of Centre-State Relations: Emerging TrendsDocument6 pagesDynamics of Centre-State Relations: Emerging TrendsDolly Singh OberoiNo ratings yet

- Public Administration: Key Issues Challenging PractitionersFrom EverandPublic Administration: Key Issues Challenging PractitionersNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Management (Debashis Das TGP)Document66 pagesHuman Resource Management (Debashis Das TGP)Debashis DasNo ratings yet

- An Architectural Thesis Presented To The: Expected Month and Year of GraduationDocument8 pagesAn Architectural Thesis Presented To The: Expected Month and Year of GraduationDenise LaquinonNo ratings yet

- CHALLENGES IN IMPLEMENTING CLINICAL GOVERNANCE Copy 2Document7 pagesCHALLENGES IN IMPLEMENTING CLINICAL GOVERNANCE Copy 2diniNo ratings yet

- Acr Demonstration On Conduct On Reading Activity of Catchup FridayDocument6 pagesAcr Demonstration On Conduct On Reading Activity of Catchup FridayJessica TorresNo ratings yet

- SocietalImpacts Journal TemplateDocument5 pagesSocietalImpacts Journal TemplateGregorio PisaneschiNo ratings yet

- Revisi JurnalDocument10 pagesRevisi Jurnalkhofiyatul jannahNo ratings yet

- Spam Filter Based Security Evaluation of Pattern Classifiers Under AttackDocument6 pagesSpam Filter Based Security Evaluation of Pattern Classifiers Under AttackChandan Athreya.SNo ratings yet

- Understanding Grammar and Vocabulary Assessment SlideDocument78 pagesUnderstanding Grammar and Vocabulary Assessment SlideNhungNo ratings yet

- BSC and MSC Subject DistributionDocument16 pagesBSC and MSC Subject DistributionManoj KumarNo ratings yet

- Ielts Writing PlanDocument7 pagesIelts Writing PlanJony SaifulNo ratings yet

- Research Design, Method and AnalysisDocument16 pagesResearch Design, Method and AnalysisMark James VinegasNo ratings yet

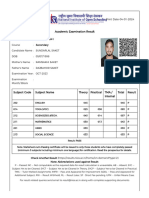

- Result - National Institute of Open SchoolingDocument2 pagesResult - National Institute of Open Schoolingwwwsundar856No ratings yet

- 05 Ma Journalism and Mass CommunicationDocument40 pages05 Ma Journalism and Mass CommunicationVickyNo ratings yet

- Importance of Global DemographyDocument3 pagesImportance of Global DemographyGuia LeeNo ratings yet

- Module 6 AssignmentDocument4 pagesModule 6 AssignmentMollyNo ratings yet

- UCSP - Q1 - Mod1 - Starting Points For The Understanding of Culture Society and PoliticsDocument31 pagesUCSP - Q1 - Mod1 - Starting Points For The Understanding of Culture Society and PoliticsmlucenecioNo ratings yet

- Ecee Helpguide 2018 19Document19 pagesEcee Helpguide 2018 19Nikol CubidesNo ratings yet

- Organizational Behaviour 3rd YearDocument11 pagesOrganizational Behaviour 3rd YearRiyaz RangrezNo ratings yet

- J. R. Kantor - Psychology and Logic - Vol. I. 1-Principia Press (1945)Document385 pagesJ. R. Kantor - Psychology and Logic - Vol. I. 1-Principia Press (1945)Alejandro CalocaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 - Planning and Scheduling - Pert-CpmDocument65 pagesLesson 3 - Planning and Scheduling - Pert-CpmChrysler VergaraNo ratings yet

- Thesis Proposal Simplified Frame Final For RobbieDocument12 pagesThesis Proposal Simplified Frame Final For RobbieMichael Jay KennedyNo ratings yet

- The Meaning of Politics PDFDocument3 pagesThe Meaning of Politics PDFJhon Leamarch Baliguat100% (2)

- Course Plan - BBA681 - Final Year Research ProjectDocument17 pagesCourse Plan - BBA681 - Final Year Research ProjectRajni KumariNo ratings yet

- The Application of Instructional Management Based Lesson Study and Its Impact With Student Learning AchievementDocument9 pagesThe Application of Instructional Management Based Lesson Study and Its Impact With Student Learning AchievementMarcela RamosNo ratings yet

- Management Theory and Projects (RECO 7074) Introduction 2019Document26 pagesManagement Theory and Projects (RECO 7074) Introduction 2019To Pui LamNo ratings yet

- Chapter I Final EditDocument9 pagesChapter I Final EditDivine BernasNo ratings yet

- Factors Affecting Performance in Clinical Practice Among Preservice Diploma Nursing Students in Northern TanzaniaDocument7 pagesFactors Affecting Performance in Clinical Practice Among Preservice Diploma Nursing Students in Northern TanzaniaStel ValmoresNo ratings yet

- Research 2022Document32 pagesResearch 2022edwinNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument3 pagesDepartment of Education: Republic of The PhilippinesUHM KI JOONNo ratings yet

- Operation Research Note CompleleDocument40 pagesOperation Research Note ComplelefikruNo ratings yet