Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Foster, Peggy. Inequalities in Health

Uploaded by

Muhammad NasherCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Foster, Peggy. Inequalities in Health

Uploaded by

Muhammad NasherCopyright:

Available Formats

Inequalities in health: what health systems can and cannot do

Author(s): Peggy Foster

Source: Journal of Health Services Research & Policy , July 1996, Vol. 1, No. 3 (July

1996), pp. 179-182

Published by: Sage Publications, Ltd.

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26750296

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Sage Publications, Ltd. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

Journal of Health Services Research & Policy

This content downloaded from

152.118.24.31 on Tue, 28 Sep 2021 04:55:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

-? t-i- r^~

Inequalities in health: what health systems can

and cannot do

Peggy Foster

Department oi social roncy ana 5ociaJ worK, ine university oi Manchester, uk

Health promotion activities are actively encouraged in most countries, including the UK Meanwhile many health care

providers and health experts are becoming increasingly concerned about the growing evidence of significant health

inequalities between social groups in the UK, and in particular the strong association between relative deprivation

and poor health. In 1995, a report for the British government entitled 'Variations in health: what can the Department

of Health and the NHS do?', identified the need for the Department of Health and the NHS to play a key role

in coordinating and implementing public health programmes intended to reduce inequalities in health. Examination

of existing evidence on the effectiveness of health promotion and prevention programmes designed to improve

the health status of the most vulnerable groups in society reveals very little evidence to support current enthusiasm

for adopting public health strategies in order to reduce variations in health status between the affluent and the

poor. Alternative and potentially more effective health care responses to inequalities in health status need to be

considered.

Journal of Health Services Research and Policy Vol. 1 No. 3,1996:179-182 © Pearson Professional Ltd 1996

Introduction report concluded that 'the weight of evidence continues

to point to explanations which suggest that socio

In October 1995, a working group in the UK published

economic circumstances play the major part in subse

a report entitled 'Variations in health: what can the

quent health differences', and that 'certain living and

Department of Health and the NHS do?'1 The group

working conditions appear to impose severe restrictions

concluded that the main explanation for observed

on an individual's ability to choose a healthy lifestyle'.2

differences in health and life expectancy between social

In 1993, participants at a seminar that focused on possi

groups was 'the cumulative differential exposure to health

ble policies to reduce inequalities in health, reinforced

damaging or health promoting physical and social envi

the growing consensus that a reduction in poverty would

ronments.' They also stated that 'it is probably the case

be an essential part of any strategy to reduce inequalities

that access to health services plays a much greater part

in health. A summary of their discussions stated, 'A

in ameliorating the effects of health variations than in

worthwhile agenda for tackling inequalities in health

preventing or reducing them'. In other words, access to

must... include a strong focus on reducing poverty.. ,'s

health services does not play a significant role in prevent

Yet, despite this growing consensus that economic in

ing variations in health status.

These conclusions are not new. Social scientists re equality creates health inequalities, the UK government

and many health experts continue to propose elaborate

searching variations in health status have been stressing

public health schemes for tackling inequalities in health,

the importance of socio-economic inequalities as a key

including the Variations in Health working group. If we

determinant of inequalities in health status for well over

examine their recommendations more closely, we find

a decade. In 1980, a report for the Department of Health

that many of their recommendations involved a signifi

concluded that 'while the health service can play a sig

nificant part in reducing inequalities in health, measures increase in resources for public health programmes.

cant

For example, the group complained that all too fre

to reduce differences in material standards of living at

quently public health programmes to date had been

work, in the home and in everyday social and commu

'time limited, funded from non-recurring sources and

nity life are of even greater importance. We have in mind

marginal to mainstream health authority activity'. It then

not simply a general reduction of inequalities in living

went on to advocate the allocation of 'mainstream re

standards, but a marked improvement in the living

sources' to public health programmes, albeit with the

standards of the poorest people'.8 In 1987, a follow-up

very strong proviso that these programmes must be care

fully costed and then evaluated rigorously to determine

their cost-effectiveness. But on what existing evidence of

Peggy Foster, Lecturer in Social Policy, Department of Social Policy

and Social Work, The University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. the effectiveness of such programmes did the working

group base its recommendations?

J Health Serv Res Policy Volume 1 Number 3 July 1996 179

This content downloaded from

152.118.24.31 on Tue, 28 Sep 2021 04:55:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Perspective Inequalities in health: what health systems can and cannot do

What evidence is there that public health or an improvement in health knowledge. Virtually no

interventions reduce inequalities in evidence was provided of an improvement in health

health? status itself. For example, Marsh and Channing8 did not

provide any evidence that the health status of their

There appears to be remarkably little evidence ofdeprived

any patients had improved as a result of their in

significant positive impact of health care interventions

creased use of preventive services. Similarly, the study

intended to improve the health status of the most vulner

which achieved a small improvement in Asian women's

able groups in our society. A recent review of the re

uptake of cervical smear testing noted without comment

search evidence identified 94 studies which satisfied all that all the smear test results for the women who came

the review inclusion criteria. Their report was based onforward for testing were normal.6 This can only mean

these. It concluded - with some regret - 'that the evi that this intensive health promotion drive did not in any

dence to date on practical public health interventions way improve the health status of the particular women

in which the NHS might engage to reduce variation intargeted, since they were not suffering from any of the

health is, at best, scant'.4 Some 'successful' interventionscervical abnormalities which the smear test is intended

were identified, though a closer examination of some to pick up.

of these interventions reveals the problematic nature of Members of the review team concluded that 'Health

much of that 'success'. Three key weaknesses in these care professionals have been rightly criticised for assum

successful studies can be readily detected. ing that what they do is effective, and evaluation has

First, the changes achieved were usually small. For shown some cherished treatments to be of little use. It is

example, a study by McAvoy and Raza,5 which aimed toequally important that strategies developed to reduce in

increase attendance for cervical smear testing among equalities are not assumed to be having a positive impact

Asian women who received a home visit and a video on simply because the aim is "progressive" and so rigorous

cervical screening in their own language, only achievedevaluations of promising interventions are important'.9

an attendance rate of 30% in the group offered a In fact, there is already a large body of evidence which

visit.

Although this figure was much higher than the 5% at

challenges the optimistic assumptions made in many of

tendance rate in the control group, it does not comparethe 94 studies reviewed that either an increased uptake

very favourably with the national average take-up rateof ofa preventive service or an increased knowledge of

over 80%.6 Another 'successful' intervention by James healthy behaviours will improve the health status of de

et al,7 which was based on a programme of dietary prived

educa groups.

tion given to a selected group of young mothers living inFive of the intervention studies reviewed had at

a deprived inner city area in Britain, managed to raise

tempted to tackle inequalities in relation to the risk of

the mean score of the children's dietary content fromsuffering from heart disease by altering adults' diets. Yet

5.3 to 7.6 (maximum score 12). The authors concluded according to a number of experts it is virtually impossi

that 'It was encouraging to find that the improvementble

in to prevent heart disease through altering the dietary

the dietary scores following the intervention was behaviours

sup of free-living subjects. For example, in 1991

a review article by Ramsay et al10 examined the results of

ported by the mothers' perception of this improvement,

without the introduction of additional finance'. However,

16 trials designed to use dietary changes to lower serum

the reviewers of this study commented, 'The impact cholesterol

of concentrations in mainly middle-aged men.

this intervention was small despite its intensity'.4 The authors of this review article claimed that the results

Second, the small changes reported in the studies

from these trials strongly suggested that, although the

deemed by the review team to have been successful type

were of dietary changes now being advocated by health

only achieved by intensive interventions which werepromotion specialists might well be acceptable and were

'probably perfectly safe', they were simply not effective

uncosted. For example, the study by James et al,7 which

because the reduction in fat intake was not severe

improved the dietary scores of the children of young

enough to produce any useful fall in a subject's choles

mothers living in deprivation, involved intensive home

terol

visiting by health visitors. On average, each mother re level. Very rigorous diets had been shown to reduc

cholesterol concentrations 'substantially' but such diets

ceived between 8-9 hours of one-to-one teaching about

healthy eating. Yet the cost of this programme waswere not 'unpleasant'. They concluded that, whilst relatively

calculated. Similarly, a study by Marsh and Channing,8 painless dietary changes, such as a small reduction in th

proportion of fat in an individual's diet, might be harm

which reported a significant increase in uptake of a range

lessinin themselves, the official promotion of such dietary

of preventive services provided by a general practice

changes could be considered harmful on the ground

north-east England, documented that the intensive effort

that

involved in achieving this increase had included a lot of scarce resources were being wasted on useless types

of intervention.

extra clerical work and some home visits by doctors

specifically to carry out preventive interventions. HowThree of the 94 studies reviewed had attempted to

ever, whilst the authors of this study acknowledgedimprove

the ethnic minority women's uptake of breast can

cer screening,

cost implications of such intensive effort, they provided two successfully and one unsuccessfully.

no costing for their own study. The reviewers commented on the successful study by

Third, most of the success documented was limitedZavertnik

to et al,11 'This study presents reasonable evidence

that an intensive community intervention can improve

an increase in the uptake of preventive health services,

180 J Health Serv Res Policy Volume 1 Number 3 July 1996

This content downloaded from

152.118.24.31 on Tue, 28 Sep 2021 04:55:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Inequalities in health: what health systems can and cannot do Perspective

uptake of breast screening and reduce the proportion of sources from the middle classes to the poor. The UK

breast cancers diagnosed at late stages'.4 However, critics government continues to back the medical consensus on

of breast cancer screening programmes have pointed the need for an expansion of public health programmes

out that earlier diagnosis of breast cancer should not be and has strongly supported moves within the NHS to

equated with the discovery of a curable disease.12 Until give a much greater priority to clinical prevention and

breast cancer specialists can guarantee a cure for very health promotion programmes. However, health policy

early breast cancers, the effectiveness of mass screening makers may wish to ask themselves what they will be

remains highly questionable. Some experts have also creating when they devote more resources to public

emphasized the very high economic cost of mass breast health programmes based very firmly on a medical

cancer screening programmes. According to Wright and model of health promotion. It might turn out to be a

Mueller, for example,'If a mean figure of population variant of the Emperor's new clothes.

benefit is accepted from the randomised clinical trials

around 20 000 women would have to be screened for

What should be done?

1 to benefit. At a low overall cost of US$60.00 (£28) per

mammogram, the cost of each woman benefited is US$1.2 In the 1970s many critics of the NHS accused it of be

a

million (£558 000)'.13 Any full cost-benefit analysis ofsickness rather than a health service, and called for fa

mass screening programmes must also take account more of resources to be devoted to preventive health care.1

the well-documented psychological and physical harm In retrospect, this demand may have been misguide

Good health is the product of a very complex range

imposed on individuals who receive a false positive test

factors, most of which are, unfortunately for health ca

result. This includes the trauma of receiving a temporary

diagnosis of breast cancer and the increased likelihood

providers, completely outside their control. Yet par

of undergoing further, more invasive, investigations.14,15 for political reasons, and partly as a consequence of t

view that modern medicine would be effective if on

Finally, it is important to note that several of the studies

it intervened earlier and more often in individuals' liv

in the review were unsuccessful, even according to their

own limited evaluative criteria. For example, a studyhealth

by promotion activities are currently absorbing e

increasing

Hoare et al,16 evaluating the impact of home visits by a amounts of scarce health care resourc

linkworker who personally invited Asian women for Given the inevitability of limitations on overall heal

breast cancer screening, found no overall difference care

in resources, maybe the time has come for hea

attendance rates between the targeted group and the policy-makers to take a stand against a medical cons

control group. Another outreach programme which pro sus which proposes ever-increasing costly interventi

vided an educational video on the dangers of smoking in the lives of healthy individuals. It may well be po

during pregnancy to pregnant women living in inner cally impossible within the foreseeable future for pol

city areas in the USA did not produce a reductionmakersin to consider a redistribution of resources aw

smoking that was statistically significant.17 from public health programmes and towards direct

come redistribution to the poor. It may be more feasible

however, for those managing health care services to

The policy response to the evidence

sider switching resources from public health programme

of unproven effectiveness to acute services of prov

If all the evidence strongly suggests that further attempts

to reduce inequalities in health through public health

effectiveness which are at present distributed in w

programmes are likely to prove ineffective whilst absorb

which disadvantage those groups already suffering fr

ing significant amounts of health care resources, we may

the worst health in our society.

well ask why any government would continue to support For example, working class women who are diagnos

activity in this area of health care? One answer is that

as suffering from breast cancer die sooner than mid

those given the task of creating strategies to reduce

class women, and some health care experts have s

inequalities in health are predominantly health care

gested that this inequality is at least partly the result

specialists. For example the 'Variations in Health' report

middle class women receiving better quality treatme

was produced by 13 members, comprising three public rather than earlier detection. Breast cancer specialis

health doctors, a nurse manager, a professor of general have claimed that if all breast cancer patients were treat

practice and a senior medical civil servant. It is hardlyin specialist centres more women would live longer.19

true, this would use extra health care resources, but

surprising, therefore, that this group gave health services

a key role in tackling inequalities in health status despite

can at least hypothesize that such a development mig

their acknowledgement that the primary causes of in do more to reduce inequalities in health than labo

equalities lay outwith health care. Another reason why intensive, and therefore costly, attempts to persuad

expenditure on health care continues to rise at a time women from deprived areas to accept mammograph

when expenditure on other welfare services suchscreening as of unproven effectiveness. It has also bee

housing and social security is being cut back or rigidly claimed that ensuring better access to coronary arte

controlled is that health care is particularly popular withsurgery for people with coronary heart disease in d

the public. Politicians know that health care initiatives prived areas may help to reduce inequalities in de

such as national screening programmes are far more

rates.9 Again this policy might well prove more effectiv

politically popular than any attempts to redistributein

re tackling inequalities in health amongst middle-ag

J Health Serv Res Policy Volume 1 Number 3 July 1996 1

This content downloaded from

152.118.24.31 on Tue, 28 Sep 2021 04:55:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Perspective Inequalities in health: what health systems can and cannot do

men than intensive health education programmesinequalities

which in health: an agenda for action. London:

King's of

attempt to change, against all the odds, the behaviour Fund, 1995

4. NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Review of the

those living in poverty. research on the effectiveness of health service

Inequalities in access to acute health services can

interventions to reduce variations in health: CRD Report

affect not just mortality rates but also the quality of The University of York, 1995

3. York:

5. McAvoy B R, Raza R. Can health education increase

individuals' lives. John Yates50 has recently highlighted

uptake

the inequality in waiting times for routine but of cervical smear testing among Asian women?

life

British Medical Journal 1991; 302: 333-336

enhancing operations, such as cataract surgery and hip

6. NHS Cervical Screening Programme National Co

replacements, which exist between patients who can Committee. Report of the first five years of the

ordinating

afford private health care and those who cannot.NHSYates

cervical screening programme. Oxford: NHSCSP,

1994

claims that 'we are now returning to a health care system

7. Jamesto

beset by the very inequality the NHS was designed J, Brown J, Douglas M, Cox J, Stocker S. Improving

the diet of under five's in a deprived inner city practice.

remove.' Lack of resources is not the only cause Health

of long Trends 1992; 24:161-164

waiting lists for certain types of operations, but under

8. Marsh G N, Channing D M. Narrowing the health gap

funding is undoubtedly part of a 'lethal cocktail'between

which a deprived and an endowed community. British

Medical

creates long and extremely inequitable waiting times forJournal 1988; 296:173-176

9. Arblaster L, Lambert M, Entwistle V et al. A systematic

surgery. Any meaningful attempt to create more equal

review of the effectiveness of health service interventions

access to acute health care will therefore involve extra

aimed at reducing inequalities in health. Journal of

expenditure, but there is at least some evidence to suggestHealth Services Research and Policy 1996; 1: 93-103

that this expenditure, if very carefully targeted, could

10. Ramsay L, Yeo W, Jackson P. Dietary reduction of serum

produce real health gains amongst deprived groups. cholesterol concentration: time to think again. British

Medical Journal 1991; 303: 953-957

11. ZavertnikJJ, McCoy C B, Love N. Breast cancer control

Conclusion program for the socio-economically disadvantaged.

Screening mammography for the poor. Cancer 1994;

Policies designed to equalize access to acute health

74(suppl): 2042-2045

services would clearly do nothing to tackle the 12. Skrabanek P, McCormick J. Follies and fallacies in

under

medicine. Glasgow: The Tarragon Press, 1989

lying causes of inequalities in health status. They might,

13. Wright C J, Mueller C B. Screening mammography and

however, prove much more cost-effective in tackling the

public health policy: the need for perspective. Lancet

results of deprivation than either health promotion1995;pro346: 29-32

grammes which attempt the Herculean task of changing P. Women and the health care industry.

14. Foster

the unhealthy behaviours of those living in deprived Buckingham: Open University Press, 1995

15. Lidbrink E, ElfvingJ, Frisell J, Jonsson E. Neglected

circumstances, or preventive measures of unproven ef

aspects of false positive findings of mammography in

fectiveness. Not only is there virtually no empirical evi cancer screening: analysis of false positive cases

breast

dence to support the widely held belief that public health

from the Stockholm trial. British Medical Journal 1996;

312: 273-276

programmes could play a significant role in reducing

16.social

unacceptable inequalities in health between Hoare T, Thomas C, Briggs A, Booth M, Bradley S,

Friedman E. Can the uptake of breast cancer screening by

groups, but their very existence may well draw every

Asian women be increased? A randomized trial of a

one's attention away from the underlying socio-economic

linkworker intervention. Journal of Public Health

Medicine 1994; 16(2): 179-185

inequalities which so greaüy contribute to the health

status variations which health experts are now 17.

seeking

Price J H, Desmond S M, Krol R A, Losh D P, Snyder F F.

to eliminate. Comparison of three anti-smoking interventions among

pregnant women in an urban setting: a randomised trial.

Psychological Reports 1991; 68: 595-604

References 18. Garner L. The NHS: your money or your life.

Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1979

19. Sainsbury R, Haward B, Rider L.Johnston C, Caroline R.

1. Department of Health. Variations in health: what can

the Department of Health and the NHS do? London: Influence of clinician workload and patterns of treatment

Department of Health, 1995 on survival from breast cancer. Lancet 1995;

2. Townsend P, Davidson N, Whitehead M. Inequalities in345:1265-1270

health. Basingstoke: Penguin Books, 1988 20. Yates J. Private eye, heart and hip. Edinburgh: Churchill

3. Benzeval M, Judge K, Whitehead M, eds. Tackling Livingstone, 1995

182 J Health Serv Res Policy Volume 1 Number 3 July 1996

This content downloaded from

152.118.24.31 on Tue, 28 Sep 2021 04:55:22 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Efficacy, Effectiveness And Efficiency In The Management Of Health SystemsFrom EverandEfficacy, Effectiveness And Efficiency In The Management Of Health SystemsNo ratings yet

- The Demand For Health Theory and Applications PDFDocument12 pagesThe Demand For Health Theory and Applications PDFCarol SantosNo ratings yet

- InecqualityDocument11 pagesInecqualitypratamayossi41No ratings yet

- Economics of Prevention Mar16Document8 pagesEconomics of Prevention Mar16Emman ImbuidoNo ratings yet

- Zayyana Musa T-PDocument34 pagesZayyana Musa T-PUsman Ahmad TijjaniNo ratings yet

- SAGE Open Medicine 2: 2050312114522618 © The Author(s) 2014 A Qualitative Study of Conceptual and Operational Definitions For Leaders inDocument21 pagesSAGE Open Medicine 2: 2050312114522618 © The Author(s) 2014 A Qualitative Study of Conceptual and Operational Definitions For Leaders inascarolineeNo ratings yet

- 5 StarDocument13 pages5 StarSofie Hanafiah NuruddhuhaNo ratings yet

- 5 - Star - Doctor - WHO With Cover Page v2Document14 pages5 - Star - Doctor - WHO With Cover Page v2elenaetxavier12No ratings yet

- AJAN 25-2 Massey PDFDocument5 pagesAJAN 25-2 Massey PDFBOBNo ratings yet

- Needs Analysis For ChangeDocument7 pagesNeeds Analysis For ChangeMoses PaulNo ratings yet

- Anderson 2009Document18 pagesAnderson 2009Noviani RestaNo ratings yet

- Neoliberaslismo en APS AustraliaDocument10 pagesNeoliberaslismo en APS AustraliaJM LNo ratings yet

- Health Policy: Kristin Farrants, Clare Bambra, Lotta Nylen, Adetayo Kasim, Bo Burström, David HunterDocument8 pagesHealth Policy: Kristin Farrants, Clare Bambra, Lotta Nylen, Adetayo Kasim, Bo Burström, David HunterowusuesselNo ratings yet

- DS 331 ExamDocument16 pagesDS 331 Examchris fwe fweNo ratings yet

- Managment Process - Sahira JastaniyhDocument10 pagesManagment Process - Sahira Jastaniyhsahira.jas96No ratings yet

- Health Promot. Int. 2000 Raphael 355 67Document14 pagesHealth Promot. Int. 2000 Raphael 355 67hilmyhaydar28No ratings yet

- Telaah Jurnal METPENDocument16 pagesTelaah Jurnal METPENaida fahleviNo ratings yet

- A Decade of Health Sector ReformDocument21 pagesA Decade of Health Sector ReformJUAN PABLO SANCHEZ LEMUSNo ratings yet

- Theory of Demand For Health CareDocument11 pagesTheory of Demand For Health CareAnupama DasNo ratings yet

- The Five-Star Doctor: An Asset To Health Care Reform?Document8 pagesThe Five-Star Doctor: An Asset To Health Care Reform?andrewsiahaan90No ratings yet

- Health Promotion: An Integral Discipline of Public HealthDocument6 pagesHealth Promotion: An Integral Discipline of Public HealthUsman Ahmad TijjaniNo ratings yet

- Population Health Systems Kingsfund Feb15Document40 pagesPopulation Health Systems Kingsfund Feb15Anonymous IUFzAW9wHGNo ratings yet

- The Health Inequalities Assessment Toolkit: Supporting Integration of Equity Into Applied Health ResearchDocument6 pagesThe Health Inequalities Assessment Toolkit: Supporting Integration of Equity Into Applied Health ResearchAna Porroche-EscuderoNo ratings yet

- Ros and TFDocument3 pagesRos and TFゝ NicoleNo ratings yet

- Practicing Health Promotion in Primary CareDocument6 pagesPracticing Health Promotion in Primary CareAlfia NadiraNo ratings yet

- CHN Journal ReadingDocument4 pagesCHN Journal ReadingKrizle AdazaNo ratings yet

- Physical Activity Promotion in Physiotherapy Practice: A Systematic Scoping Review of A Decade of LiteratureDocument7 pagesPhysical Activity Promotion in Physiotherapy Practice: A Systematic Scoping Review of A Decade of Literaturearaaela 25No ratings yet

- MATHEMATICS 8 Quarter 4 Module 5Document15 pagesMATHEMATICS 8 Quarter 4 Module 5JA M ESNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Cash Transfers On Social Determinants of Health and Health Inequalities in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic ReviewDocument22 pagesThe Impact of Cash Transfers On Social Determinants of Health and Health Inequalities in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Reviewlight1plusNo ratings yet

- Aminu Magaji T-PDocument27 pagesAminu Magaji T-PUsman Ahmad TijjaniNo ratings yet

- NQF Roadmap For Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities Sept 2017Document119 pagesNQF Roadmap For Promoting Health Equity and Eliminating Disparities Sept 2017iggybauNo ratings yet

- Tacking The Wider Determinants of Health InequalityDocument8 pagesTacking The Wider Determinants of Health InequalitymammaofxyzNo ratings yet

- What Is "Community Health Examining The Meaning of An Evolving Field in Public HealthDocument4 pagesWhat Is "Community Health Examining The Meaning of An Evolving Field in Public Healthد.شيماءسعيدNo ratings yet

- Ibrahim Halliru T-PDocument23 pagesIbrahim Halliru T-PUsman Ahmad TijjaniNo ratings yet

- NHS Economic Appraisal of Public Health Interventions 2005Document8 pagesNHS Economic Appraisal of Public Health Interventions 2005Juan DuoNo ratings yet

- 0rder 335 - Policy and Advocacy For Population HealthDocument6 pages0rder 335 - Policy and Advocacy For Population Healthjoshua chegeNo ratings yet

- Hapl04 Nutpob Docrelac Jacoby EngDocument4 pagesHapl04 Nutpob Docrelac Jacoby EngRosmira Agreda CabreraNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2213076418300654 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S2213076418300654 MaindaytdeenNo ratings yet

- What Contribution Can Health Economics Make To Health Promotion?Document8 pagesWhat Contribution Can Health Economics Make To Health Promotion?nencydhamejaNo ratings yet

- Metode Menurunkan MerokoDocument7 pagesMetode Menurunkan MerokoCecepNo ratings yet

- Public Health Policy: January 2003Document17 pagesPublic Health Policy: January 2003feyisamideksa117No ratings yet

- Health PromotionDocument5 pagesHealth Promotionplug rootedNo ratings yet

- Healt (15384)Document110 pagesHealt (15384)Oscar Javier Gaitan TrujilloNo ratings yet

- 5 Star DoctorDocument25 pages5 Star DoctorNadzira KarimaNo ratings yet

- Undertandin Dsiparities in Health.Document8 pagesUndertandin Dsiparities in Health.MaximilianoNo ratings yet

- Equity of Access To Health Care: Theory & Aplication in ResearchDocument8 pagesEquity of Access To Health Care: Theory & Aplication in ResearchNoviana ZaraNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion: The Tannahill Model Revisited: Andrew TannahilllDocument5 pagesHealth Promotion: The Tannahill Model Revisited: Andrew TannahilllShanindya NaurashalikaNo ratings yet

- Intersectoral Coordination in India For Health Care AdvancementDocument26 pagesIntersectoral Coordination in India For Health Care Advancementshijoantony100% (1)

- Community Health Factors and Health DisparitiesDocument7 pagesCommunity Health Factors and Health Disparitiesshreeguru8No ratings yet

- Public Health in The New Era Improving HDocument3 pagesPublic Health in The New Era Improving HIsa LemaNo ratings yet

- Workplace Stressors & Health Outcomes: Health Policy For The WorkplaceDocument12 pagesWorkplace Stressors & Health Outcomes: Health Policy For The WorkplaceLarisa BuneaNo ratings yet

- Intersectoral Coordination in India For Health Care AdvancementDocument26 pagesIntersectoral Coordination in India For Health Care Advancementlimiya vargheseNo ratings yet

- Gha 9 29329Document19 pagesGha 9 29329Bahtiar AfandiNo ratings yet

- 1994 - Eleven Worthy Aims For Clinical Leadership of Health System Reform.Document6 pages1994 - Eleven Worthy Aims For Clinical Leadership of Health System Reform.Daniel MeloNo ratings yet

- BASCOLO Et Al - Types of Health Systems Reforms in LA - 2018 PDFDocument9 pagesBASCOLO Et Al - Types of Health Systems Reforms in LA - 2018 PDFJuan ArroyoNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion and Disease Prevention in General Practice and Primary Care A Scoping StudyDocument12 pagesHealth Promotion and Disease Prevention in General Practice and Primary Care A Scoping StudyFaissuly DiazNo ratings yet

- Change Management in An Environment of Ongoing Primary Health Care System Reform A Case Study in AustraliaDocument13 pagesChange Management in An Environment of Ongoing Primary Health Care System Reform A Case Study in AustraliaTengiz VerulavaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Translation and Behaviour Change: Patients, Providers, and PopulationsDocument2 pagesKnowledge Translation and Behaviour Change: Patients, Providers, and PopulationsyodaNo ratings yet

- Reducing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Reproductive and Perinatal Outcomes: The Evidence from Population-Based InterventionsFrom EverandReducing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Reproductive and Perinatal Outcomes: The Evidence from Population-Based InterventionsArden HandlerNo ratings yet

- PERDEV2Document7 pagesPERDEV2Riza Mae GardoseNo ratings yet

- Family Code Cases Full TextDocument69 pagesFamily Code Cases Full TextNikki AndradeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Basic-Concepts-Of-EconomicsDocument30 pagesChapter 1 Basic-Concepts-Of-EconomicsNAZMULNo ratings yet

- JAR66Document100 pagesJAR66Nae GabrielNo ratings yet

- A Brief Introduction of The OperaDocument3 pagesA Brief Introduction of The OperaYawen DengNo ratings yet

- The Aesthetic Revolution and Its Outcomes, Jacques RanciereDocument19 pagesThe Aesthetic Revolution and Its Outcomes, Jacques RanciereTheoria100% (1)

- WAS 101 EditedDocument132 pagesWAS 101 EditedJateni joteNo ratings yet

- Snyder, Timothy. The Reconstruction of Nations. Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999 (2003)Document384 pagesSnyder, Timothy. The Reconstruction of Nations. Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569-1999 (2003)Ivan Grishin100% (8)

- Module 4 - Starting Your BusinessDocument8 pagesModule 4 - Starting Your BusinessJHERICA SURELLNo ratings yet

- Homicide Act 1957 Section 1 - Abolition of "Constructive Malice"Document5 pagesHomicide Act 1957 Section 1 - Abolition of "Constructive Malice"Fowzia KaraniNo ratings yet

- Greek Gods & Goddesses (Gods & Goddesses of Mythology) PDFDocument132 pagesGreek Gods & Goddesses (Gods & Goddesses of Mythology) PDFgie cadusaleNo ratings yet

- Test 5Document4 pagesTest 5Lam ThúyNo ratings yet

- BloggingDocument8 pagesBloggingbethNo ratings yet

- Crisis Communications: Steps For Managing A Media CrisisDocument15 pagesCrisis Communications: Steps For Managing A Media Crisismargarita BelleNo ratings yet

- Returns To Scale in Beer and Wine: A P P L I C A T I O N 6 - 4Document1 pageReturns To Scale in Beer and Wine: A P P L I C A T I O N 6 - 4PaulaNo ratings yet

- Smart Notes Acca f6 2015 (35 Pages)Document38 pagesSmart Notes Acca f6 2015 (35 Pages)SrabonBarua100% (2)

- KPMG Our Impact PlanDocument44 pagesKPMG Our Impact Planmuun yayo100% (1)

- Frias Vs Atty. LozadaDocument47 pagesFrias Vs Atty. Lozadamedalin1575No ratings yet

- A.jjeb.g.p 2019Document4 pagesA.jjeb.g.p 2019angellajordan123No ratings yet

- G.R. No. 187730Document10 pagesG.R. No. 187730Joses Nino AguilarNo ratings yet

- Sculi EMT enDocument1 pageSculi EMT enAndrei Bleoju100% (1)

- Pre-Paid: Pickup Receipt - Delhivery Challan Awb - 2829212523430 / Delhivery Direct Standard Order ID - O1591795656063Document1 pagePre-Paid: Pickup Receipt - Delhivery Challan Awb - 2829212523430 / Delhivery Direct Standard Order ID - O1591795656063Sravanthi ReddyNo ratings yet

- Cir Vs PagcorDocument3 pagesCir Vs PagcorNivra Lyn Empiales100% (2)

- 3-16-16 IndyCar Boston / Boston Grand Prix Meeting SlidesDocument30 pages3-16-16 IndyCar Boston / Boston Grand Prix Meeting SlidesThe Fort PointerNo ratings yet

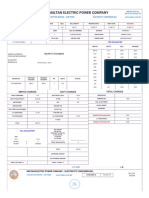

- Multan Electric Power Company: Say No To CorruptionDocument2 pagesMultan Electric Power Company: Say No To CorruptionLearnig TechniquesNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument37 pagesIntroductionA ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- Rainiere Antonio de La Cruz Brito, A060 135 193 (BIA Nov. 26, 2013)Document6 pagesRainiere Antonio de La Cruz Brito, A060 135 193 (BIA Nov. 26, 2013)Immigrant & Refugee Appellate Center, LLCNo ratings yet

- Docs in Int'l TradeDocument14 pagesDocs in Int'l TradeRounaq DharNo ratings yet

- 2020 HGDG Pimme Checklist 16Document2 pages2020 HGDG Pimme Checklist 16Kate MoncadaNo ratings yet

- Memorandum1 PDFDocument65 pagesMemorandum1 PDFGilbert Gabrillo JoyosaNo ratings yet