Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1970 - Jing-Shen Tao - The Influence of Jurchen Rule On Chinese Political Institutions

Uploaded by

fatih çiftçiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1970 - Jing-Shen Tao - The Influence of Jurchen Rule On Chinese Political Institutions

Uploaded by

fatih çiftçiCopyright:

Available Formats

The Influence of Jurchen Rule on Chinese Political Institutions

Author(s): Jing-shen Tao

Source: The Journal of Asian Studies, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Nov., 1970), pp. 121-130

Published by: Association for Asian Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2942726 .

Accessed: 18/06/2014 23:03

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Association for Asian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The

Journal of Asian Studies.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.174 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 23:03:21 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

The Influence of Jurchen Rule on

Chinese Political Institutions

JING-SHEN TAO

S INCE the Sung dynasty there was a continuous trend toward the establishment of

a highly centralized despotism, which matured in the Ming and Ch'ing pe-

riods.' This paper is a preliminary attempt to assess the influence of the Chin pe-

riod (III5-I234) on the Chinesepoliticalsystem,with emphasison the bearingof

alien rule on this institutional evolution.

Long before the rise of the Liao and Chin dynasties, there had existed a number

of alien dynasties of infiltration in North China during the period of disruption

(220-581 A.D.), or what Prof. Tamura Jitsuzo calls the period of barbarianmigration,

in comparison with the barbarian invasions in Europe.2 Some of these dynasties,

such as the T'o-pa Northern Wei and the Northern Chou, left important traces on

the fu-ping militia institution, the chiin-t'ien (equal-field) system, and T'ang bu-

reaucracy.3During and after the tenth century, the increasing barbarian infiltration

led to the formation of first the Liao state, and later its successor,the Chin. The two

together mark the rise of conquest dynasties, climaxed by the establishment of the

Yuan and Ch'ing empires.

In terms of cultural change, there are two patterns under conditions of conquest.

The Ch'i-tan nomads of the Liao, on the one hand, display a cultural pattern under

which there only occurred limited acculturation and there generally existed a dual

political and social system-Chinese institutions were employed to administer the

Chinese majority, and tribal organizations were retained for the conquerors them-

selves. Bearing resemblance to the T'o-pa Wei, the Jurchen agriculturists of the

Chin, on the other hand, set up another pattern of Sino-barbariansynthesis under

which the conquerors gave up a large part of their indigenous way of life. It should

be noted, however, that although the Chin came to be assimilated by the Chinese

tradition, it also tried to preserve some of its own heritages, and its success in

China owed much to the adoption and modification of Liao dualistic practices.

Similarly the Yuan and Ch'ing inherited from both the Liao and Chin institu-

Jing-shen Tao is Associate Research Fellow at infiltration rather than conquest. Tamura Jitsuz6

Academia Sinica and Associate Professor of History points out that these dynasties of infiltrationare the

at National Taiwan University. The abridged ver- results of great waves of barbarianmigration sim-

sion of this paper was originally presented at the ilar to the barbarian invasions in Europe. See his

2Ist Annual Meeting of the Association for Asian pamphlet, "Yuboku minzoku to n6k5 minzoku

Studies in March I969. tono rekishi teki kankei" (The Historical Relations

1 For a general treatment of the trend, see F. W. between the Nomads and Agriculturists), issued by

Mote, "The Growth of Chinese Despotism," Oriens Ky6to University in I968, pp. 2-5.

Extremus, Vol. 8, No. I (I96I) I-4I. 3 See Ch'en Yin-k'o, Suz-t'ang chih-tu yuan-yuan

2 Karl A. Wittfogel and Feng Chia-sheng in their lAieh-lunkao (Draft Essay on the Origins of Sui-

Historyof ChineseSociety:Liao (907-1125) (Phil- T'ang Institutions), reprinted by Academia Sinica,

adelphia, I949) pp. I5-I6 assert that the dynasties n.d.

during the period of disruption are dynasties of

121

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.174 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 23:03:21 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

122 JING-SHEN TAO

tional and cultural features, with important modifications and varying emphases.

All the dynasties of conquest encountered two fundamental problems: that of

enhancement of the tribal chieftain's authority in order to marshal effectively the

manpower and resourcesfor conquests, and, after the conquest of part or the whole of

China, that of the establishment of a Sino-barbarianstate in which alien rule was

consolidated. The Jurchen solutions to these problems, which were closely related,

seem to have required measures of centralized control, which they partly inherited

from their tribal experience, and partly adopted from the Liao and Sung. In gen-

eral the Mongols, and especially the Manchus, provided similar solutions.

I. The InitialPeriodof DualisticRule andPoliticalStruggles

The Jurchen were a people of Tungusic origin, who had lived in Manchuria

since time immemorial, and had practiced farming, hunting, and fishing as their

way of life. They founded permanent settlements in the forest zone in eastern

Manchuria, indicated by remains of their towns, villages, and fortresses. After the

tenth century their power gradually grew as they relied upon the breeding of the

horse to organize predatory raids and invasions of the Liao and Koryo.4 By iII5

they had enlarged their domain and established a periphery state between Liao and

Koryo. Within a period of twelve years (III5-II26) this formidable group of war-

riors not only conquered the Liao and the Northern Sung, but also subdued Koryo

and the Hsi Hsia kingdom in West China.

The Jurchen rulers generally followed the Liao example of dualistic rule during

the initial phase of conquest. They retained tribal organization to administer their

own subjects, and adopted Chinese institutions to control the conquered majority. In

the early twelfth century the leaders of the basic tribal socio-political units were the

meng-an (the head of a thousand men) and the mou-k'e (the head of a hundred to

three hundred men), who in case of war became military officers,leading the tribes-

men to the battleground, and acting as local officials in the newly acquired land. In

addition to the reconstitution of these units into an efficient military system in III4,

Wan-yen A-ku-ta (io68-iI23), the founder of the state, organized a hierarchy of

higher officials, called the po-chi-lieh, above the meng-an and mou-k'e. Under Wan-

yen Wu-ch'i-mai (reign: II23-II35), A-ku-ta's brother and successor, political sin-

icization began with the introduction of some Chinese institutions in II26. It did not,

however, result in significant changes in the Jurchen central government in Man-

churia, for the major Chinese institution, the Chancellery (shu-mi yuan), was set

up in North China under the Jurchen generals, regulating Chinese affairs.5The re-

forms of II34-II35, initiated by Wu-ch'i-mai and Tan (reign: II35-II49), were noted

for the borrowing of the Chinese three council system and the abolition of the tribal

officials such as the po-chi-lieh. The purpose of these reforms was mainly for

4 See Jing-shen Tao, "The Horse and the Rise ence with Wu-ch'i-mai in Manchuria until II34,

of the Chin Dynasty," Papers of the Michigan when he was appointed Right Prime Minister of

Academy of Science, Arts, and Letters, LIII (I968) the newly reformed central government. The case

I 83-I 89. of Han also indicates the powerful position held by

5 The situation is evident in the career of Han the generals in North China, who, in fact, com-

Chi-hsien, who assumed the position of Chanceller pleted A-ku-ta's unfinished task of conquest. See

in II128. Han, however, always stayed in North Chin Shih (Dynastic History of the Chin. Po-na

China, never having the chance to have an audi- ed.; hereaftercited as CS), 78.8ab.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.174 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 23:03:21 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JURCHEN RULE 123

achieving a centralized government to cope with the problem of decentralization.'

Among the three councils, however, authority was monopolized by the Presidential

Council (shang-shu sheng), which was the administrative branch, while the func-

tion of the other two, the Secretarial Council (chung-shu sheng) and the Court

Council (men-hsia sheng), was obscure and unimportant.7 Furthermore, old tribal

practices bearing some "democratic"tendencies gradually disappeared,whereas some

of the methods in tribal politics tinged with barbarismwere introduced into the new

political system.

The fading of the primitive "democratic"practices is indicative in the emergence

of an unequal relationship between the tribal ruler and his subjects. It is recorded

that A-ku-ta never required the officials to perform the kowtow ceremony at his

court in the early years of his reign, and Wu-ch'i-mai had taken bath with his

tribesmen in the same river.8 In addition, there was a tribal council in which im-

portant policies were discussed and determined collectively2 It seems that a few

important decisions were still made in this manner during the reigns of Wu-ch'i-mai

and Tan. One example is the debate at Tan's court on the policy concerning the

territory south of the Yellow River when the Liu Yiu puppet regime was abolished in

II37.10 It is interesting to note that such debate did not ease any tension among the

leaders and only provoked violent political struggles. The adoption of Chinese values

and symbols centering upon the exaltation of the emperor and other political changes

created a gap between the ruler and his officials, not to mention that between him

and his subjects.The political struggles entailed the brutalization of the political proc-

ess, not a combination of the political compromises and conflicts of the T'ang-Sung

periods and Jurchen"democratic"elements.

In general, the reigns of Tan and Liang (reign: II49-II6I) witness two develop-

ments. First, there was the brutal elimination of tribal influence on politics which was

largely represented by the warlords and by the rise of an incipient feudalism in

North China. Second, together with and especially after the destruction of the war-

lords and feudal forces, Chinese institutions, values and customs were borrowed on

a large scale. In fact, during the struggles between the central government and the

regional forces, men in the government continuously drew experiences and methods

from the Chinese, along with coercion and suppression, to deal with the recalcitrant

generals and imperial clansmen. Consequently when Chinese institutions were in-

troduced, most tribal practices had to go, except the military organization, on which

the new state was founded. But a centralized control was also devised in this respect."

It is a recurrent theme in medieval Chinese history that there were conflicts be-

tween bureaucratsand aristocrats.These conflicts occurred in the T'o-pa Wei and the

Northern Chou, and it was largely because of the need for diminishing the hered-

itary privilegs of the aristocracy that the examination system was implemented in

6 For details see Mikami Tsugio, "Kinsho ni 9 Ibid., 3.7.

okeru sansho seido, Part I" (The Three Depart- 10 CS, 78, "Biographyof Ta-lan."

ment System for Central Government in the Early 11 In the early years the highest authority in

Chin Dynasty), Rekishi to Bunka, V (I96I) I5I. military affairs was held by generals such as Nien-

7 Ibid., I 29-I 5 2. han and Wa-li-pu. Later the Chancellerytook over

8Hsii Meng-hsin, San-ch'ao pei-meng hui-pien their power. Cf. CS, 44. The Chancellery, unlike

(Compendium on the Northern Alliance under the that of the Northern Sung, was controlled by the

Three Reigns: Iioi-iI6I. Taipei: Wen-hai ed.; Presidential Council. See CS, II4.8b.

hereaftercited as SCPM) 3.3; I66.5.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.174 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 23:03:21 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

124 JING-SHEN TAO

T'ang times.12Like what had happened before, it seems that in the new Jurchen

state the rulers were divided into two groups. Supported by formal Liao and Sung

officials and newly recruited bureaucrats, a group of administrators remained loyal

to the emperor and advocated institutional reforms. The other group of generals and

aristocratswanted to have a weak government so that their own authority in their

respective domains could be maintained. The bureaucrats under Tan and Liang

reconstituted the government in order to establish a centralized bureaucracy pat-

terned after that of China. One of the most important leaders of this group was

Wan-yen Wa-pen. Not a military man, Wa-pen was distinctly different from the

other leaders in the early Chin, who were mostly either formidable warriors or bril-

liant strategists. Wa-pen seldom left the capital in Manchuria, and his family was

under strong Chinese and P'o-hai influence. He hired Chinese teachers for his sons

and also Tan, who was raised in his house.13As a result of this educational back-

ground, Tan reportedly could compose Chinese poems, loved Chinese classics, and

"lost all the Jurchen manners and attitude." Looking like a young Chinese scholar,

he even regarded the old founders of the dynasty as "ignorant barbarians."'4Natur-

ally Wa-pen was the most influential man during Tan's reign.

Another protagonist of Chinese culture was Wan-yen Hsi-yin, originally a sha-

man. Hsi-yin was so fascinated by Chinese classics that he collected a library when

the Jurchen captured Pien-ching, the capital of the Northern Sung. He treated

Chinese scholars kindly, and always tried to learn from them. Like Wa-pen, Hsi-yin

also employed several Chinese teachers to teach his sons and grandsons.'5 Conse-

quently the classical education of his children was good enough for them to write

Chinese poems and exchange them with the famous Chinese scholar Hung Hao

when Hung was detained in Manchuria.'6 One of Hsi-yin's sons was among the

first Jurchen to have a Chinese wife. Yii-wen Hsii-chung, a teacher hired by Hsi-yin,

was a prominent scholar, on whose advice Hsi-yin introduced many Chinese institu-

tions in the early Chin.'7

In regard to adopting Chinese institutions, some Jurchen administrators showed

a dynamism characteristic of first-generation conquerors and nation-builders. Men

like Wan-yen Hsi-yin and Wan-yen Tsung-hsien favored Chinese political organiza-

tion and proposed a selective borrowing of old as well as new Chinese elements.

Tsung-hsien thought it unnecessary to imitate Liao dualistic institutions and prob-

ably this was the consensus among the administrators, for the Jurchen did go be-

yond the Liao experience and assumed direct control of North China.18 This flex-

ible attitude perhaps contributed to the establishment of a bureaucracycomprised of

not only Sung and Liao elements but also some T'ang institutions.

12 Cf. Edwin G. Pulleyblank, The Background "Chiao chin wan-yen hsi-yin sheng-tao-pei shu-

of the Rebellion of An Lu-shan (London: Oxford hou" (After Editing the Epigraph of Wan-yen Hsi-

UniversityPress, I955) pp. 47-48. yin of the Chin), Shih-hsueh Chi-k'an, I (1936)

13 SCPM, I66.3-5; Hung Hao, Sung-mo chi-wen I 4.

(Travel Records of the Cypress and Desert Area, l6rSee Hung Hao, P'o-yang chi (San-shui-t'ang

Liao-hai ts'ung-shu ed.) I.2b. ed.) i.6ab, 8a, iob, I2b, I3b, I4ab, and Isa for

14 Yii-wen Mao-ch'ao, Ta-chin-kuo chih (His- poems written by Hung for Hsi-yin's sons.

tory of the Great Chin Kingdom. In Ssu-ch'ao 17 Ibid., i.iia; 4I.oa.

pieh-shih, Sao-yeh shan-fang ed.) I2.3b-4a. 18 CS., 70.3b.

15 See Hsi-yin's epigraph in Hsii Ping-ch'ang,

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.174 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 23:03:21 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JURCHEN RULE 125

Among the warlords favoring a strong regionalism, the most important was

Wan-yen Nien-han, who had taken part in putting Tan on the throne. Another was

Ta-lan, who with Nien-han sponsored the Liu Yii puppet regime in North China,

and later convinced the administrators in the aforementioned debate that most ter-

ritory in North China should be returned to the Southern Sung when the inept

puppet regime was abolished. Furthermore they were responsible for launching a

Jurchenizing movement in the early Chin, in which the Chinese were forced to

adopt Jurchen hair style, clothing, and customs.19 The descendants of Wu-ch'i-mai,

such as P'u-lu-hu, were also against centralized control. All these warlords eventually

lost their powerful positions, even their lives, in the struggle with the emperor and

his bureaucrats.20Wan-yen Tan, however, only enjoyed a temporary triumph, for he

finally was murderedby his cousin Liang.

The brutalization of the political process also extended to high-ranking Chinese

officials. Alongside the execution of a few Chinese advisers of the ousted military

leaders, a few others were deliberately framed and eliminated.2' While these cases

and the death of Chang Chiun, a Chinese Han-lin Academician, at the hands of the

semi-insane emperor Tan could be interpreted as terror inflicted by an individual ty-

rant rather than organized violence, these incidents provide a sharp contrast with the

fact that no high-ranking officialshad ever been punished in the same manner dur-

ing the Northern Sung dynasty. Furthermore, the Jurchen rulers ruthlessly pun-

ished Chinese officialsinvolved in factional struggles. In one case alone eight officials

were executed and thirty-four banished.22 Such intimidation naturally resulted in

the total silence of Chinese officialson state affairs.

2. The InteractionbetweenCentralizationand Sinicization

With the decline of the warlords and aristocratsand the rise of the emperor and

his bureaucrats, the dualistic institutions were gradually changed into centralized

ones, and the government continuously broadened its scope to rule both Jurchen

and Chinese subjects in the state. Having abolished the Chinese puppet regime in

II37, the Jurchenfinally were readyto assumedirectrule of North China in II40.

As an important measure for direct control, the Chancellery was replaced by a Mo-

bile Presidential Council (hsing-t'ai shang-shu sheng), headed by a few Jurchen

administrators loyal to the central government. The major business of the Mobile

Presidential Council was the management of Chinese affairs, such as the recruit-

ment of Chinese bureaucrats through the civil service examinations. It marks an

important step in the expansion of government power in North China, for the coun-

cil, as its name indicates, was a branch of the Presidential Council in the central

government, instead of an instrument under the recalcitrant generals in earlier

19 Tiao-fa lu (Records of Consoling the People dropped. Finally even Hsi-yin could not manage to

and Punishing the Rebels. Ssu-pu ts'ung-k'an 3rd escape from the fate of being eliminated.

ser. ed.) 2.6. 21 Cf. Toyama Gunji, "Sansei o chfishin toseru

20 Nien-han was deprived of his military power kinsh6 sokan no katsuyaku" (Chin General Tsung-

in North China, while his adviser Kao Ch'ing-i han's Activities Centering upon Shansi), Toyo5shi

was executed. P'u-lu-hu and O-lu-kuan allegedly Kenkyui,Vol. i, No. 6 (I936) 509-532.

plotted against Tan, but Tan forestalled in action 22For some details of the case of T'ien Chiueh

and killed them. Ta-lan was executed in II39 and see CS,89.5a-7a.

his scheme for peace with the Southern Sung was

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.174 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 23:03:21 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

126 JING-SHEN TAO

years.23It is worth noting that although Wan-yen Liang abolished the council in

II50, it was revived in the last years of the dynasty, and was adopted by the Mon-

gols. In fact it was the predecessor of the Yuan provincial system, which developed

into the modern provinces. The term hsing-e'ai chung-shu sheng (Mobile Secre-

tarial Council) in the early Yuan period is the forerunner of the modern hsing-

sheng, and is similar in its function to the hsing-t'aishang-shu sheng of early Chin.24

In national policies Wan-yen Liang not only followed the measures initiated by

his predecessors,but also greatly accelerated the pace toward the building of a cen-

tralized state. In the processhe adopted a great deal of Chinese ideas and institutions,

but not without making some alterations and modifications. As usurper and cham-

pion of the Chinese culture, Liang had his reasons to increase centralized control

and to curb the power of the Jurchen aristocracy.Admiration of the Chinese culture,

on the one hand, stimulated his ambition to set up a genuine and legitimate Chi-

nese dynasty; fear of the conservative Jurchen aristocrats and hereditary elements

such as the meng-an and mou-k'e, on the other hand, compelled him to use force to

suppress opposition. The result was the enforced transformationof the Jurchen tribal

organization into a sinicized political system, with much more centralized authority

in the central government than that of the Northern Sung.

In order to build a legitimate Chinese dynasty, Liang followed the policy of Wu-

ch'i-mai and Tan to borrow Chinese ritual-symbolic practices at the imperial court,

and to construct ancestral as well as Confucian temples. He stopped the Jurcheniz-

ing movement and moved most of the Jurchen population from Manchuria to

North China. He rebuilt Yen-ching as his new capital, which with its magnificent

buildings was described by visitors as more elaborate and ornate than Pien-ching.25

Perhaps because of the foundations laid by the Jurchen at Yen-ching, the city became

not only the capital of the Mongols, who thus had China Proper as the center of the

huge Mongol empire, but also that of the Ming and Ch'ing dynasties, the early Re-

public, and Communist China.

Liang radically reformed the bureaucracyin II50 when he abolished the Mobile

Presidential Council, and in iI56 when he did away with the Secretarial Council

and the Court Council.26The II50 measure ended the period of dualistic administra-

tion and the II56 reform marked the beginning of a new era in the history of the

Chinese political system. The Secretarial Council was the originator of policies and

the Court Council a check on the authority of the emperor in Sui and T'ang times.

Although in the Northern Sung the power of the administrative council grew con-

siderably, the very existence of three councils ensured a relatively enlightened

despotism. But Liang as an alien ruler was not restricted by Chinese tradition and

could disregard whatever checks and balances existed in the Chinese political heri-

23 It was called a "Mobile" council because its bile Presidential Council in the Chin Dynasty),

site was not fixed at a single place and it exercised Taihaku teikoku daigaku bunsei gakubu shigaku

a flexible rule of first the area north of the Yellow ka kenkylinembo,No. I(I934) I5I-I62; Aoki

River, and then the whole of North China. Cf. Tomitar6, "Gensho gyoja k6" (Studies of the Prov-

Mikami Tsugio, "Kinsho ni kodai shoshosho yo ince in Early Yuan), Shigaku Zasshi, Vol. 5I, Nos.

kore o meguru seiji jo no sho mondai" (On Hsing- 4-5 (5940) 480-50I and 6I4-645.

t'ai shang-shu-sheng of Chin Dynasty and Its Po- 25Fan Ch'eng-ta, Shih-hu chui-shih shih-chi

litical Problems), Rekishi to Bunka, IV (I959) (Ssu-pu ts'ung-k'an ed.), I2.II; Chou Lin-chih,

61-72. Hai-ling chi (Hai-ling tszung-k'e ed.), Appendix,

24 For

detailed discussions see Aoyama Kosuke, p. 2.

"Kincho kodai shoshosh k6 ' (Studies of the Mo- 26 CS, 5.6a and I4ab; 55.Ib-2a.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.174 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 23:03:21 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JURCHEN RULE 127

tage. It is also likely that the Jurchen rulers in general did not fully understand the

function of certain complicated institutions and they preferred a more simplified

government.27 The simplified bureaucratic system persisted until the fall of the

dynasty and the three council organization was never restored in later dynasties. It

should be emphatically pointed out, therefore, that the reform of 1156 was the culmi-

nation of attempts to build a centralized despotism. Along with some other measures

treated in the following paragraphs,it left a remarkableimprint on Chinese political

history.

As many usurpers in Chinese history did, immediately after his enthronement

Liang started to rid himself of a number of aristocratswho had the potentiality to

threaten his position. Several princes and their families met the fate of mass execution

with the consequence of extermination of the lineage of the second ruler Wu-ch'i-

mai, so that the predominant prestige of A-ku-ta's descendants, including Liang

himself, could be secured.28Related to this terrorism was the corporal punishment

of important officials,which seemed to be one of his techniques to promote the au-

thority of the emperor. Although corporal punishment of minor officials had existed

in China prior to the Chin period, the flogging of officialswith whips and poles was

much more common among the Ch'i-tan and Jurchen tribes. In the early Chin it

was retained by A-ku-ta. Later it became a common punishment for misbehaved

officials, Chinese as well as Jurchen, and developed into a notorious practice when

Liang enjoyed watching its execution right at his court. Records show that approxi-

mately 5o persons, including prime ministers, high-ranking officials, censors, mili-

tary officers,monks, a cook and a princess, were flogged at his court.29Lou Yiieh, a

Southern Sung envoy to the Chin, observed that neither Chin officials nor scholars

could ever keep away from the punishment of beating. When Lou was en route to

the Chin capital, a local official complained to him: "Although my rank is very high,

I cannot be exempted from beating. What kind of life is this!""3This uncivilized

practice, called t'ing-chang later, was obviously a deliberate means to belittle and

humiliate the hitherto much respected scholar-officialsin Chinese society, and was

followed by the Yuan and Ming rulers.3'

Among the officials beaten at the court of Liang, as shown above, there were a

few censors. This fact signifies that another Chinese institution was degraded and it

retreated into silence.32Such practice was continued by Liang's successors. Each of

27 Cf. Mikami Tsugio, "Kinsho ni okeru sansh6 of the Yuan, Po-na ed.) 50.Ib, 2a, and I3a. Ex-

seido, Part I," I48-I52; Part II, Rekishito Bunka, amples of officialsflogged are in ibid., I9.4b; 24.3b;

VI (i963) 9I-92. 32.22ab, 24b; 34.26b; 35.I3b. It is generally be-

28 Cf. Jing-shen Tao, "Chin sung ch'ien ti chin lieved that the t'ing-chang was first used in the

hai-ling-ti" (On Emperor Hai-ling of the Chin Yuan period. See F. W. Mote, "The Growth of

before His Invasion of the Southern Sung), Yu-shih Chinese Despotism," pp. 27-28. For this practice

Journal, Vol. 3, No. I (I960) 7-I2. in the Ming period see Meng Sheng, Ming-tai shih

29 Jing-shen Tao, Chin hai-ling-ti ti la-sung yui (History of the Ming Dynasty; Taipei, I957) pp.

ts'ai-shih chan-i ti k'ao-shih (A Study of the Chin 8i-82; Charles 0. Hucker, The Traditional Chi-

Emperor Hai-ling's Invasion of the Southern Sung nese State in Ming Times (I368-1644) (Tucson:

and the Battle of Ts'ai-shih, Ii6i. Teipei: National The University of Arizona Press, I96I) p. 48; and

Taiwan University, I963) pp. I5-i8. his The Censorial System of Ming China (Stan-

30 Lou Yiieh, Kung-k'uei chi (Ssu-pu ts'ung-k'an ford: Stanford University Press, I966) p. 3i8.

ed.) iii.iib. 32 Cf. Mikami Tsugio, "Kin no gyoshidai to sono

31 During the Yuan period there was a distinc- seiji shakai teki yakuwari" (The Political and So-

tion between ch'ih (whipping) and chang (flog- cial Role of the Censorate of the Chin Dynasty),

ging), the latter of which involved beating with Rekishi to Bunka, IX (I967) I-7I.

a bamboo pole. See Yuan Shih (Dynastic History

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.174 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 23:03:21 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

128 JING-SHEN TAO

his two successorsflogged at least two censors.33The power of the censors was thus

limited, a fact borne out by the memorial submitted by a censor in I2I6: "Although

our dynasty has censors, they are only sinecurists.... The duty of the censors in-

cludes merely supervising the officials, checking documents, and inspecting trea-

suries."34In other words, the censor's power of remonstration with the emperor

weakened. Their main function seems to have been holding the administrative in-

stitutions and the high officials in check. Possessing the special privilege of having

direct contact with the emperor, the censors acted as if they were the spies sent out

by the emperor.35Even in this respect the censors did not enjoy monopoly, for the

eunuchs also performed the same function during the later Chin period.36Thus the

authority of the emperor was enhanced and one of the most important functions of

the censorial officials, namely the criticisms of policies and remonstration with the

emperor about his abberations,was gradually impeded.37

3. The Civil Service Examination System as a Stabilizing Factor

Two essential methods were employed by the Jurchen to consolidate their rule in

China: the use of the meng-an mou-k'e system to exercise military control, and the

implementation of the Chinese civil service examination system to enlist Chinese

cooperation. In the early Chin examinations were held to recruit Chinese officialsfor

the Chancellery to manage Chinese affairs. Later the examination system was de-

vised to enlist Chinese assistance to administer the entire state and even to balance

the power of the Jurchen aristocracy.

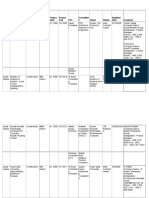

During the initial phase of conquest, the Jurchen government discriminated

against the Chinese population south of the Yellow River by allowing them a

smaller quota of chin-shih degrees than that for the people north of the river, in-

cluding non-Jurchen residents in Manchuria, who were trusted by the Jurchen. The

examinations given in the two regions were also different. The northerners took

examinations on poetry and prose, while the subject matter for the southerners was

classics. The regional quotas, however, were abolished by II64. The government

began to recruit as many degree holders as possible after ii83, a fact indicating the

broadening of the base of the government.38In general the Chinese so recruited only

exerted limited influence on the formulation of policies. Usually important positions

in both the central and local governments were taken by the Jurchen. During the

era of Tan and Liang the Jurchen entering into the civil service outnumbered other

peoples: 55.I percent for the Jurchen, 26.4 percent for the Chinese, and I8.5 for

the others. If one considers the number of appointments (a person is counted once

whenever the government appointed him a 'different position), the proportions

are even more striking: 62.7 percent for the Jurchen, I9.I percent for the Chinese,

and I 8.2 percent for the others. Important positions such as the Three Teachers,

33 CS, 8.2a; Ioo.4b. and Ming dynasties. See Charles 0. Hucker, The

341Ibid., i o9. 8 b9a. CensorialSystem of Ming China, pp. 25-28 (Yuan)

35 Mikami Tsugio, "Kin no gyoshidai to sono and passim.

seiji shakai teki yakuwari," pp. 28-29 and 4I-43. 38 Teng Ssu-yii, Chung-kuo k'ao-shih chih-tu

36 Mikami Tsugio, "Kinch6 ni okeru sh6shosho shih (A History of Chinese Examination System.

no kenkyfi, Part II" (A Study of the Presidential Taipei, I966) pp. 189-I93 and 20I-202. In the

Council of the Chin Dynasty), Rekishi to Bunka, early Chin the quota for the chin-shih from the

VII (1965) 41-44. northern region was 200 while that for the south-

37 This development is discernible in the Yuan ern region was 150.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.174 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 23:03:21 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

JURCHEN RULE 129

Three Dukes, Chief of the Three Councils, Prime Ministers, etc., were seldom given

to non-Jurchen peoples. Military commanders were almost exclusively Jurchen. Chi-

nese officials, nevertheless, continued to increase their influence throughout the rest

of the dynasty.89

For the Chinese, the chin-shih degree was an important qualification for obtaining

higher positions in both central and local governments. Before ii6i among 4I high-

ranking Chinese officials there were I9 holding the chin-shih. For the rest of the dy-

nasty the number of chin-shih increased to 64 out of 90 Chinese officials. For the

Ch'i-tan, P'o-hai, and other non-Jurchen peoples, the chin-shih degree was not so

important. Of 37 high-ranking non-Jurchen and non-Chinese officials during the

entire dynasty only eight ever held the degree.40

In the early Chin period the Jurchendid not have to take the examinations in order

to obtain government positions. Wan-yen Wu-lu (reign: ii6I-iI89), however,

created the Jurchen chin-shih degree in II73 and encouraged his tribesmen to ac-

quire it.41 The new policy primarily aimed at the training of teachers to teach the

Jurchen language and to translate Chinese books into Jurchen. It perhaps also had

the function of diminishing the power of the aristocracyby promoting the quality of

Jurchen officialsand channeling more Jurchen commoners into the officialdom. The

first appointment for the Jurchen degree holder was generally not higher than that

of his Chinese counterpart.42Wu-lu, therefore, was one of the few alien rulers who

had ever tried to curb the excessive growth of their tribesmen's prestige, privileges,

and power. Unfortunately his successorsmerely wanted to maintain their privileged

position; they were contented with the immediate gains and did not attempt to

eliminate corruption, favoritism, and selfishness among themselves. Only a few

Jurchen were interested in acquiring the chin-shih. Of 208 top-ranking officials, only

26 had this qualification. Apparently the chin-shih degree never became an important

approach toward success. Many entered the government from military service;

others received good jobs through protection; still others started their career with

some unimportant positions which had the advantage of being close to the throne.

A few Jurchen were able to ascend in the officialdomby merely studying the Jurchen

language.43In short, although Wu-lu's attempt to modify the Chinese civil service

examination system by developing a Jurchen system of recruitment parallel to that

of the Chinese eventually failed, both the Mongols and the Manchus introduced sim-

ilar measures in their initial phase of conquest, perhaps imitating the Jurchen prec-

edent.44 Furthermore, both peoples adopted the examination system to establish a

coalition government. While under the Mongols it only exerted limited influence,

it did contributeto the stability of Jurchen and Manchu rule in China.

39 Jing-shen Tao, "Chin-tai ch'u-ch'i nii-chen ti amination degrees equally among the four ethnic

han-hua" (The Sinicization of the Jurchen in the groups. The policy was perhaps an imitation of the

Early Chin Period), Bulletin of the College of Arts, Jurchen example, but Yuan examinations only

National Taiwan University, XVII (I968) 53-54. played a very limited role. See E. A. Kracke, Jr.,

40 Ibid., 54. "Region, Family, and Individual in the Chinese

41 CS, 5I.Iia-i 2a. Examination System," in John K. Fairbank (ed.),

42 Teng Ssu-yii, Chung-kuo k'ao-shih chih-tu Chinese Thought and Institutions (Chicago and

shih, p. 209. London, I957), p. 263. Cf. also Teng Ssu-yii, op.

43 Jing-shen Tao, "Chin-tai ch'u-ch'i niu-chen ti cit., pp. 2II-2I3. In the early years of the Ch'ing

han-hua," 54. period the rulers adopted a similar quota system in

"The Mongols also balanced the several ethnic favor of the Manchus. See ibid., p. 255.

elements in their bureaucracyby dividing the cx-

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.174 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 23:03:21 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

130 JING-SHEN TAO

Conclusion

In the presentation above, the influence of Jurchen rule on the formation of a cen-

tralized despotism can be seen in several aspects: the establishment of a prototype

of the provincial system, the abolition of important government councils, the mo-

nopoly of state affairs by a single administrative branch of the government, the de-

gradation of the scholar-officialsby inflicting corporal punishment, and the transfor-

mation of the censorate into an imperial instrument. These changes were mostly

negative, entailing the brutalization of the political process and the simplification of

political institutions. The alien conquerors could not stand the political compromises

and conflicts in the Chinese civilization, and, as represented by the shrewd tyrant

Liang, they seem to have enjoyed organized brutality.

It is interesting to note that in correspondencewith a continuous growth of the

power of the central government in North China, there was a similar trend in the

south toward the strengthening of the monarchy. The Southern Sung tried to mo-

bilize as much manpower and resources as possible to defend itself against Jurchen

invasions and to deal with other disintegrating elements such as economic crises,

widespread banditry, and growing regionalism. This preoccupation with self-defense

and survival, together with some other factors, perhaps entailed the rise of conser-

vatism and centralized control during the Southern Sung.45 Especially interesting is

the parallel in political practices: the three-council system in the south underwent a

similar simplifying reconstitution in which the administrative organ began to mo-

nopolize state power and the emperor played a more important role in decision-

making.46 Perhaps the very existence of two rival states, frequently engaged in a

life-and-death struggle with each other, assisted and promoted the growth of des-

potism in both states. Parallels in the south notwithstanding, a contrast in political

practices which were much more brutal in the north than those in the south shows

clearly the magnitude of barbarian influence. The influence is still more striking

because the successors of the Chin followed the Jurchen way of government, not

that of the Southern Sung. As a successor state of the Northern Sung, the Chin not

only served as an important link in Chinese cultural and political developments, but

also, as the predecessor of the Yuan and the Ch'ing, transferred to these conquest

dynasties its institutions such as the modified examination system characteristic of

alien rule.

45 Cf. James T. C. Liu, "Sung Roots of Chinese yao-lu (Annual Records of Important Events since

Political Conservatism: the Administrative Prob- the Chien-yen Era: II27-II62. Kuan-ya ts'ung shu

lems," journal of Asian Studies, XXVI, No. 3 ed.) 22.I2ab. The other councils were abolished in

(I967) 457-463. II29.

46 See Li Hsin-ch'uan, Chien-yen i-lai hsi-nien

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.174 on Wed, 18 Jun 2014 23:03:21 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Modern China PowerpointDocument170 pagesModern China PowerpointalancstndNo ratings yet

- Sima Qian and the Shiji; A Lesson in Chinese HistoriographyDocument17 pagesSima Qian and the Shiji; A Lesson in Chinese Historiographypinidi kasturiNo ratings yet

- 1970 - Tao, Jing-Shen - The Influence of Jurchen Rule On Chinese Political InstitutionsDocument10 pages1970 - Tao, Jing-Shen - The Influence of Jurchen Rule On Chinese Political Institutionsfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- World History To 1500 A.D.-Ch3-Ancient - CDocument27 pagesWorld History To 1500 A.D.-Ch3-Ancient - Cmanfredm6435No ratings yet

- Western Zhou DynastyDocument3 pagesWestern Zhou DynastyLutfi JatmikaNo ratings yet

- Taiping Society Interpretation Tien KuoDocument11 pagesTaiping Society Interpretation Tien KuoHritika RajvanshiNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Qing DynastyDocument9 pagesResearch Paper On Qing Dynastyc9hpjcb3100% (1)

- 1974 - Luc Kwanten - Chingis Kan's Conquest of Tibet. Myth or RealityDocument21 pages1974 - Luc Kwanten - Chingis Kan's Conquest of Tibet. Myth or Realityfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- SHSHHSSHDocument6 pagesSHSHHSSHanastasyalouisNo ratings yet

- Joch Article p200 - 5Document15 pagesJoch Article p200 - 5Kototo TotoNo ratings yet

- AssignmenDocument27 pagesAssignmenNur Munirah50% (2)

- China-Centered Tributary System's Ideologies and FunctionsDocument13 pagesChina-Centered Tributary System's Ideologies and FunctionsVivian YingNo ratings yet

- Readings and Questions PacketDocument6 pagesReadings and Questions Packetapi-254303832No ratings yet

- His Ytr 731Document12 pagesHis Ytr 731samrinbluNo ratings yet

- Tsukamoto Zenryu Ch. 6 A History of Early Chinese BuddhismDocument149 pagesTsukamoto Zenryu Ch. 6 A History of Early Chinese BuddhismjaholubeckNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 27.18.137.164 On Wed, 09 Mar 2022 04:27:08 UTCDocument27 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 27.18.137.164 On Wed, 09 Mar 2022 04:27:08 UTCLynnNo ratings yet

- WHP 3-7-5 Read - Han Dynasty - 1190LDocument7 pagesWHP 3-7-5 Read - Han Dynasty - 1190LLucas ParkNo ratings yet

- Xiongnu Sima - Qian - and - The - Shiji - A - Lesson - in - HistDocument17 pagesXiongnu Sima - Qian - and - The - Shiji - A - Lesson - in - HistxopoxNo ratings yet

- Secular ChangesDocument6 pagesSecular ChangesSayan LodhNo ratings yet

- Development Admininstration in ChinaDocument51 pagesDevelopment Admininstration in ChinaEdgardo Apuhin JrNo ratings yet

- Tang SongDocument7 pagesTang SongMeredith BanksNo ratings yet

- Defining 'China' - Ancient - China - Final - Exam - d5Document18 pagesDefining 'China' - Ancient - China - Final - Exam - d5Andrew “Castaway” GroundNo ratings yet

- Explore the Diverse Traditions of Chinese CultureDocument3 pagesExplore the Diverse Traditions of Chinese Culturefaërië.aē chaeNo ratings yet

- Chinese CultureDocument3 pagesChinese Culturefaërië.aē chaeNo ratings yet

- 5 The Xiongnu Empire: Ursula BrossederDocument10 pages5 The Xiongnu Empire: Ursula Brossederfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- Sun and Secret SocietiesDocument10 pagesSun and Secret SocietiesDaniel FANNo ratings yet

- 05 - Great Disunion PDFDocument9 pages05 - Great Disunion PDFAceNo ratings yet

- Chinese History Analysis According To PROUT Economic TheoryDocument54 pagesChinese History Analysis According To PROUT Economic TheoryTapio PentikainenNo ratings yet

- Colin Mackerras - Relations Between The Uighurs and Tang Chine, 744-840 (2000)Document14 pagesColin Mackerras - Relations Between The Uighurs and Tang Chine, 744-840 (2000)ТерекемеОгузовичNo ratings yet

- Pan Yihong - Early Chinese Settlement Policies Towards The Nomads - AM - 1992Document38 pagesPan Yihong - Early Chinese Settlement Policies Towards The Nomads - AM - 1992Mehmet TezcanNo ratings yet

- Stories of The Republic of China I (Full)Document53 pagesStories of The Republic of China I (Full)AngelaNo ratings yet

- Chinese Civilizations: Dynasties, Philosophy, and CultureDocument8 pagesChinese Civilizations: Dynasties, Philosophy, and CultureNegielyn SubongNo ratings yet

- Unification and Consolidation of Civilization in ChinaDocument6 pagesUnification and Consolidation of Civilization in Chinaorderinchaos910No ratings yet

- Qing Dynasty ReligionDocument12 pagesQing Dynasty ReligiondanieNo ratings yet

- Mandarin Chinese: The Worlds Oldest CivilizationDocument8 pagesMandarin Chinese: The Worlds Oldest CivilizationCrystal BernalNo ratings yet

- Mao Zedong, Legalism and Confucianism - Similarities and Differences - The Greater China JournalDocument1 pageMao Zedong, Legalism and Confucianism - Similarities and Differences - The Greater China JournalDuyên ĐỗNo ratings yet

- The History and Philosophy of Wing Chun Kung FuDocument24 pagesThe History and Philosophy of Wing Chun Kung FuKhairunnisa Jani LubisNo ratings yet

- Mandate of HeavenDocument5 pagesMandate of HeavenMaria Lorna L. GarnaceNo ratings yet

- Asian HistoryDocument10 pagesAsian HistoryMa. Paula Fernanda Cuison SolomonNo ratings yet

- History of ChinaDocument3 pagesHistory of ChinaCharles Daniel RosiosNo ratings yet

- China AssignmentDocument6 pagesChina AssignmentAnushka PantNo ratings yet

- China: Afro-Asian Literature 2:30 - 4:00 TTHDocument13 pagesChina: Afro-Asian Literature 2:30 - 4:00 TTHEgbert Alan P. EballaNo ratings yet

- ChinaDocument5 pagesChinaMaria Jose DiazNo ratings yet

- The Xia, Shang, and Zhou Dynasties in Ancient ChinaDocument4 pagesThe Xia, Shang, and Zhou Dynasties in Ancient Chinasprite_phx073719No ratings yet

- Huang He (Yellow) River: Kiran Fatima - VI - T 1Document5 pagesHuang He (Yellow) River: Kiran Fatima - VI - T 1Waseem3668No ratings yet

- 05 Política e Sociedade Chinesa (Inglês)Document42 pages05 Política e Sociedade Chinesa (Inglês)LuizFernandoChagasNo ratings yet

- Feudalisme 1Document31 pagesFeudalisme 1ASHLLEY ANAK KRANI BA22110657No ratings yet

- AN02c3 - Han Emperors in ChinaDocument3 pagesAN02c3 - Han Emperors in ChinaAnthony ValentinNo ratings yet

- Guest Lecture: Patricia Ebrey: Book Recommenation: Gunpowder Age - Tonio AndradeiDocument3 pagesGuest Lecture: Patricia Ebrey: Book Recommenation: Gunpowder Age - Tonio AndradeiPhil LouisNo ratings yet

- History of China: Historical SettingDocument4 pagesHistory of China: Historical Settingcamiladcoelho4907No ratings yet

- Dynasties in China: Zhou, Qin & HanDocument9 pagesDynasties in China: Zhou, Qin & HanZint PhonyNo ratings yet

- An Lushan Rebellion Lee Chamney ThesisDocument127 pagesAn Lushan Rebellion Lee Chamney ThesisToddus Aurelius100% (1)

- Background Knowledge About China and Their CultureDocument34 pagesBackground Knowledge About China and Their CultureButchNo ratings yet

- Annotated Chronological Outline of Chinese HistoryDocument3 pagesAnnotated Chronological Outline of Chinese HistorySyazwani Suif100% (1)

- Boxer Rebellion PDFDocument30 pagesBoxer Rebellion PDFbelievingiswinningNo ratings yet

- KEATINGE y CONRAD Imperialist Expansion-Chimu Administration of A Conquered Territory 1983Document30 pagesKEATINGE y CONRAD Imperialist Expansion-Chimu Administration of A Conquered Territory 1983Brad ReeseNo ratings yet

- 1986 - Igor de Rachewiltz - BRIEF COMMENTS ON PROFESSOR YÜ TA-CHÜN'S ARTICLE ON THE DATING OF THE SECRET HISTORY OF THE MONGOLSDocument6 pages1986 - Igor de Rachewiltz - BRIEF COMMENTS ON PROFESSOR YÜ TA-CHÜN'S ARTICLE ON THE DATING OF THE SECRET HISTORY OF THE MONGOLSfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1984 - Ruth W. Dunnell - Who Are The Tanguts Remarks On Tangut Ethnogenesis and The Ethnonym TangutDocument13 pages1984 - Ruth W. Dunnell - Who Are The Tanguts Remarks On Tangut Ethnogenesis and The Ethnonym Tangutfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1978 - John W. Haeger - MARCO POLO IN CHINA PROBLEMS WITH INTERNAL EVIDENCEDocument10 pages1978 - John W. Haeger - MARCO POLO IN CHINA PROBLEMS WITH INTERNAL EVIDENCEfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 41927102Document34 pages41927102fatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1981 - Kuhn, Dieter - Silk Technology in The Sung Period (960-1278 A.D.)Document43 pages1981 - Kuhn, Dieter - Silk Technology in The Sung Period (960-1278 A.D.)fatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1971 - Ayalon, David - The Great Yasa of Chingiz Khan. A Reexamination (Part A)Document45 pages1971 - Ayalon, David - The Great Yasa of Chingiz Khan. A Reexamination (Part A)fatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1949 - Robert P. Blake and Richard N. Frye - History of the Nation of the Archers (the Mongols) by Grigor of Akancͺ Hitherto Ascribed to Matakͺia the Monk the ArmenianDocument132 pages1949 - Robert P. Blake and Richard N. Frye - History of the Nation of the Archers (the Mongols) by Grigor of Akancͺ Hitherto Ascribed to Matakͺia the Monk the Armenianfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1970 - David C. Montgomery - MONGOLIAN HEROIC LITERATUREDocument8 pages1970 - David C. Montgomery - MONGOLIAN HEROIC LITERATUREfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1977 - Harry Jackendoff - THE URIANGQAI CONNECTION, SOME SOCIAL STUDY AND TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF THE SECRET HISTORYDocument35 pages1977 - Harry Jackendoff - THE URIANGQAI CONNECTION, SOME SOCIAL STUDY AND TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF THE SECRET HISTORYfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1942 - A. N. Poliak - The Influence of C Ingiz - Ān's Yāsa Upon The General Organization of The Mamlūk StateDocument16 pages1942 - A. N. Poliak - The Influence of C Ingiz - Ān's Yāsa Upon The General Organization of The Mamlūk Statefatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1970 - V. V. BARTHOLD and J. M. ROGERS - THE BURIAL RITES OF THE TURKS AND THE MONGOLSDocument36 pages1970 - V. V. BARTHOLD and J. M. ROGERS - THE BURIAL RITES OF THE TURKS AND THE MONGOLSfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1943 - H. Desmond Martin - The Mongol ArmyDocument41 pages1943 - H. Desmond Martin - The Mongol Armyfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1951 - J. V. Mills - Notes On Early Chinese VoyagesDocument25 pages1951 - J. V. Mills - Notes On Early Chinese Voyagesfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1945 - Otto Maenchen-Helfen - The Yüeh-Chih Problem Re-ExaminedDocument12 pages1945 - Otto Maenchen-Helfen - The Yüeh-Chih Problem Re-Examinedfatih çiftçi100% (1)

- 1944 - Dunlop, D. M. - The Karaits of Eastern AsiaDocument14 pages1944 - Dunlop, D. M. - The Karaits of Eastern Asiafatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1949 - Francis Woodman Cleaves - The Mongolian Names and Terms in The History of The Nation of The Archers by Grigor of AkancͺDocument45 pages1949 - Francis Woodman Cleaves - The Mongolian Names and Terms in The History of The Nation of The Archers by Grigor of Akancͺfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- The Royal SocietyDocument33 pagesThe Royal Societyfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1925 - Lawrence Impey - Shangtu, The Summer Capital of Kublai KhanDocument22 pages1925 - Lawrence Impey - Shangtu, The Summer Capital of Kublai Khanfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 5 The Xiongnu Empire: Ursula BrossederDocument10 pages5 The Xiongnu Empire: Ursula Brossederfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1980 - Paul D. Buell - KALMYK TANGGACI PEOPLE THOUGHTS ON THE MECHANICS AND IMPACT OF MONGOL EXPANSIONDocument20 pages1980 - Paul D. Buell - KALMYK TANGGACI PEOPLE THOUGHTS ON THE MECHANICS AND IMPACT OF MONGOL EXPANSIONfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- The Royal SocietyDocument33 pagesThe Royal Societyfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1882 - B. Jülg - On The Present State of Mongolian ResearchesDocument24 pages1882 - B. Jülg - On The Present State of Mongolian Researchesfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1929 - E. Denison Ross - Nomadic Movements in Asia. Lecture IV.-Chinghiz Khan and The MongolsDocument13 pages1929 - E. Denison Ross - Nomadic Movements in Asia. Lecture IV.-Chinghiz Khan and The Mongolsfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 2010 - Vl.a. Semenov - The Wusun in Northeastern Central AsiaDocument12 pages2010 - Vl.a. Semenov - The Wusun in Northeastern Central Asiafatih çiftçi100% (1)

- 1926 - A. Neville J. Whymant - Mongolian Proverbs A Study in The Kalmuck ColloquialDocument12 pages1926 - A. Neville J. Whymant - Mongolian Proverbs A Study in The Kalmuck Colloquialfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 2015 - Kisun Kim, Sungyoung Lee and Jongoh Lee - Taboos Related To Food Culture at The 13th-14th-Century MongolsDocument11 pages2015 - Kisun Kim, Sungyoung Lee and Jongoh Lee - Taboos Related To Food Culture at The 13th-14th-Century Mongolsfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1938 - Mehdi Bahrami and Phyllis Ackerman - Some Examples of Il-Khanid ArtDocument5 pages1938 - Mehdi Bahrami and Phyllis Ackerman - Some Examples of Il-Khanid Artfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1965 - A. Róna-Tas - Some Notes On The Terminology of Mongolian WritingDocument30 pages1965 - A. Róna-Tas - Some Notes On The Terminology of Mongolian Writingfatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- 1987 - István Erdélyi, Imre Fejes - Recently Discovered Ancient Relics in MongoliaDocument17 pages1987 - István Erdélyi, Imre Fejes - Recently Discovered Ancient Relics in Mongoliafatih çiftçiNo ratings yet

- Spirituals as expressions of protest and motivationDocument2 pagesSpirituals as expressions of protest and motivationCelene RamdeoNo ratings yet

- Herrera V COMELECDocument4 pagesHerrera V COMELECTheodore BallesterosNo ratings yet

- Brgy EO GFPSDocument2 pagesBrgy EO GFPSfidel narismaNo ratings yet

- Project Name Sector Value EPC Client Status Contacts Count Ry Project Start Project End Consultan T Updated DateDocument83 pagesProject Name Sector Value EPC Client Status Contacts Count Ry Project Start Project End Consultan T Updated DateCookie CluverNo ratings yet

- IM Contemporary WOrld BSIE I 1 FinalDocument57 pagesIM Contemporary WOrld BSIE I 1 Finaljelacio mendozaNo ratings yet

- Many Personal Troubles Must Be Understood in Terms of Public IssuesDocument4 pagesMany Personal Troubles Must Be Understood in Terms of Public IssuesVũ Nguyễn Cao HuyNo ratings yet

- Lucknow Pact - WikipediaDocument8 pagesLucknow Pact - Wikipediafatima vohraNo ratings yet

- Chapter - Iv ExecutiveDocument9 pagesChapter - Iv ExecutiveWARRIOR FFNo ratings yet

- Youth Unrest: Dr. Keyoor PathakDocument10 pagesYouth Unrest: Dr. Keyoor PathakMsnish pandeyNo ratings yet

- Simon Commission 1927Document14 pagesSimon Commission 1927ABDUL HADINo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 10 Political Science (Civics) Chapter 1 Notes - Power SharingDocument4 pagesCBSE Class 10 Political Science (Civics) Chapter 1 Notes - Power Sharinggyu :No ratings yet

- George Taubman Goldie - WikipediaDocument4 pagesGeorge Taubman Goldie - WikipediaAbdullahi ChuwachuwaNo ratings yet

- Book Review - " of Blood and Fire" by Jahanara ImamDocument5 pagesBook Review - " of Blood and Fire" by Jahanara ImamSmoll CutieNo ratings yet

- Germany-20th CenturyDocument60 pagesGermany-20th Centuryapi-19505025No ratings yet

- Kpop y Hallyu Como Impulsor Del Soft Power de Corea Del SurDocument54 pagesKpop y Hallyu Como Impulsor Del Soft Power de Corea Del SurLucia Silveira PercaraNo ratings yet

- Southeast Asian Trade and DiplomacyDocument1 pageSoutheast Asian Trade and DiplomacyEric BourdonneauNo ratings yet

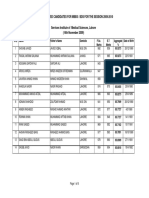

- List of Selected Candidates For Mbbs / Bds For The Session 2009-2010Document8 pagesList of Selected Candidates For Mbbs / Bds For The Session 2009-2010Engr. MohidNo ratings yet

- Gender WordsDocument2 pagesGender WordsFarkas-Szövő NikolettNo ratings yet

- LOPEZ vs. COMELEC, G.R. NO. 182701, July 23, 2008Document1 pageLOPEZ vs. COMELEC, G.R. NO. 182701, July 23, 2008Joy DLNo ratings yet

- Chapter 16 Political Crisis Obook Only PDFDocument19 pagesChapter 16 Political Crisis Obook Only PDFClaire StaffordNo ratings yet

- 1st Year - S2 - 2012Document3 pages1st Year - S2 - 2012Phan Do Dang KhoaNo ratings yet

- Comelec Resolution No. 8944Document17 pagesComelec Resolution No. 8944AggyChristineNo ratings yet

- CSS Political Science PaperDocument49 pagesCSS Political Science Papersundesh kumarNo ratings yet

- Ladakh Studies Journal 2013Document68 pagesLadakh Studies Journal 2013གཅན་བཟོད་རྒྱམ། བོད་ཡིག་ཕྲིས། བོད་སྐད་ཤོད།No ratings yet

- The Madness of Otto Von DrakDocument2 pagesThe Madness of Otto Von DrakTimNo ratings yet

- How America Does Regime-Change PropagandaDocument5 pagesHow America Does Regime-Change PropagandaJohn LawrenceNo ratings yet

- Rajni Kothari - The Congress System in IndiaDocument14 pagesRajni Kothari - The Congress System in IndiaKhushboo SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Role of Election CommissionDocument5 pagesRole of Election CommissionSuhani SinghNo ratings yet

- 209 Mps Say Yes: Anti-Party Hopping BillDocument36 pages209 Mps Say Yes: Anti-Party Hopping Billchefezani80No ratings yet

- 1 PDFDocument9 pages1 PDFThomas BarlaNo ratings yet