Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pandemic - ISBD Congress 2023

Pandemic - ISBD Congress 2023

Uploaded by

Valentina SuarezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Pandemic - ISBD Congress 2023

Pandemic - ISBD Congress 2023

Uploaded by

Valentina SuarezCopyright:

Available Formats

Changes in morbidity among bipolar I patients during pandemic-related strict lockdown: comparison

between two seven-month periods

Cecilia Samamé¹ ², Eliana Marengo², Antonella Godoy², José Smith², Sebastián Camino², Melany Oppel², María Florencia Tagni², Martina Sobrero², Lautaro López Escalona², Sergio Strejilevich²*

¹Universidad Católica del Uruguay, Montevideo, Uruguay; ²AREA, Asistencia e Investigación en Trastornos del Ánimo, Buenos Aires, Argentina; *sstreji@gmail.com

Introduction

Converging evidence supports the involvement of circadian rhythm disturbances in the course and morbidity of bipolar disorder (BD) (1-3). During 2020, lockdown measures were introduced worldwide to contain the health

crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, chronobiological rhythms were critically disrupted, leading to sleep disturbances and psychological symptoms in the general population. Within this context, a mental

health crisis was thought to be approaching and it was reasonable to expect that BD-related outcomes would worsen because of these circumstances. The current study aimed to explore changes in illness severity among

type I BD patients living in Argentina under strict lockdown.

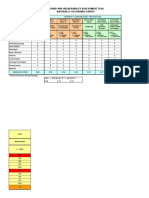

Methods Table 2. Morbidity variables across each mirror period; mean ± standard deviation (min - max).

Methods

Pre-pandemic Pandemic Wilcoxon signed-rank test

Thirty-seven adult type I BD outpatients under naturalistic treatment conditions were followed from March to

September 2020 using a mood chart technique based on the NIMH life-charting method. Nº of episodes

0.89 ± 1.70 0.70 ± 1.27

Z = -1.19, p = 0.23

(0 - 10) (0 - 7)

Sociodemographic and clinical data were obtained as well as pharmacological exposure information. Different 0.38 ± 0.92 0.24 ± 0.72

variables of illness course and severity, including mood instability, were assessed and compared with the clinical Nº of depressive episodes Z = -1.89, p = 0.06

(0 - 5) (0 - 4)

outcomes obtained during the same seven-month period in 2019. 0.35 ± 0.92 0.30 ± 0.66

Nº of manic episodes Z = -0.54, p = 0.59

(0 - 5) (0 - 3)

Between-period differences in morbidity and pharmacological measures were analyzed using non-parametric 0.16 ± 0.44 0.16 ± 0.44

Wilcoxon signed-rank test for paired data. Nº of mixed episodes Z = 0.00, p = 1.00

(0 - 2) (0 - 2)

7.08 ± 8.96 6.97 ± 9.10

Time (weeks) spent with symptoms Z = -0.03, p = 0.98

Results (0 - 28) (0 - 28)

Time (weeks) spent with depressive 3.03 ± 5.81 4.11 ± 7.18

Z = -1.27, p = 0.21

Demographic and clinical variables at baseline are shown in Table 1. No significant between-period differences symptoms (0 - 20) (0 - 28)

Time (weeks) spent with manic 2.32 ± 4.22 2.05 ± 5.28

were observed in patients’ clinical course, intensity of pharmacological treatment, or number of outpatient visits symptoms (0 - 16) (0 - 28)

Z = -0.13, p = 0.90

(Table 2). During lockdown, most patients (54%) did not exhibit any increase in mood instability or in the time Time (weeks) spent with mixed 1.73 ± 6.39 1.35 ± 4.74

spent with mood symptoms. No differences were observed between periods as regards exposure to Z = -0.05, p = 0.96

symptoms (0 - 28) (0 - 27)

pharmacological treatment (all p values > 0.05) Mood instability (nº of mood changes)

2.00 ± 2.38 1.89 ± 2.14

Z = -0.28, p = 0.78

(0 - 9) (0 - 8)

Table 1. Baseline demographic and illness characteristics of patients (n = 37). 0.00 ± 0.00 0.03 ± 0.16

No of suicide attempts Z = -1.00, p = 0.32

(0 - 0) (0 - 1)

No of previous hospital admissions, 1.27 ± 1.24 0.05 ± 0.33 0.00 ± 0.00

Females, n (%) 22 (59.5) No of hospital admissions Z = -1.00, p = 0.32

mean ± SD (min - max). (0 - 5) (0 - 2) (0 - 0)

51.92 ± 15.48 Patients with previous suicide attempts, 4.41 ± 3.39 4.16 ± 3.17

Age, years, mean ± SD (min - max). 9 (24.3) No of planned outpatient visits Z = -0.34, p = 0.74

(26 - 89) n (%) (1 - 18) (1 - 12)

25.53 ± 10.91 No of previous suicide attempts, mean ± 0.35 ± 0.68

Age at 1st episode, mean ± SD (min - max).

(12 - 55) SD (min - max). (0 – 2) Conclusions

Years of previous follow-up, mean ± SD 5.81 ± 4.24

IFD Scale - Lithium, median (IQR) 2 (1 - 2)

In line with previous longitudinal studies of BD patients (4-6), the results of this study show no worsening

(min - max). (2 - 16) in clinical morbidity or increase in the exposure to pharmacological treatment during lockdown.

No of previous depressive episodes, mean ± 4.31 ± 4.32 IFD Scale - Anticonvulsants, median

1 (0 - 2) Such a conspicuous contrast between our initial predictions and the observed findings highlights the fact

SD (min - max). (0 - 23) (IQR) that we are still far from being able to accurately predict the evolution of the disorder and the impact

No of previous manic episodes, mean ± SD 3.37 ± 1.94 that specific stressors have on illness variables.

IFD Scale - Antipsychotics, median (IQR) 2 (1 - 2)

(min - max). (0 - 8)

These results should be interpreted cautiously as the BD sample was small, and actigraphy or other

Patients with previous hospital admissions, IFD Scale - Antidepressants, median methods able to ensure significant changes in patients' physical activity were not used. Further, the

26 (70.3) 0 (0 - 0)

n (%) (IQR)

observation period was limited to a 7-month lockdown and it is possible than changes occur later in

IFD Scale: Clinical Scale of Intensity, Frequency, and Duration of Pharmacological Treatment.

time.

References

References

1. Bauer M, Glenn T, Alda M, et al. (2017) Solar insolation in springtime influences age of onset of bipolar I disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 136(6): 571–582. 4. Carta MG, Ouali U, Perra A, et al. (2021) Living With Bipolar Disorder in the Time of Covid19: Biorhythms During the Severe Lockdown in Cagliari, Italy, and the Moderate Lockdown in Tunis, Tunisia. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12:

2. Merikangas KR, Swendsen J, Hickie IB, et al. (2019) Real-time Mobile Monitoring of the Dynamic Associations Among Motor Activity, Energy, Mood, and Sleep in Adults With Bipolar Disorder. JAMA Psychiatry 634765.

76(2): 190–198. 5. Lewis KJS, Gordon-Smith K, Saunders KEA, et al. (2022) Mental health prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic in individuals with bipolar disorder: Insights from prospective longitudinal data. Bipolar Disorders 24(6): 658–666.

3. Gershon A, Do D, Satyanarayana S, et al. (2017) Abnormal sleep duration associated with hastened depressive recurrence in bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 218: 374–379 6. Yocum AK, Zhai Y, McInnis MG, et al. (2021) Covid-19 pandemic and lockdown impacts: A description in a longitudinal study of bipolar disorder. Journal of Affective Disorders 282: 1226–1233.

You might also like

- General Surgery 2002Document50 pagesGeneral Surgery 2002Breyner De Jesus García RodríguezNo ratings yet

- TAMPURADocument5 pagesTAMPURAAbril De Gracia VeranoNo ratings yet

- Topological Ideas BINMORE PDFDocument262 pagesTopological Ideas BINMORE PDFkishalay sarkar100% (1)

- India Insurtech Landscape and Trends: APRIL 2022Document70 pagesIndia Insurtech Landscape and Trends: APRIL 2022SupriyaMurdiaNo ratings yet

- Q2 MODULE 9 Physical ScienceDocument15 pagesQ2 MODULE 9 Physical ScienceG Boy100% (2)

- First Quarter - Curriculum Map - Science 8Document7 pagesFirst Quarter - Curriculum Map - Science 8Mich Hora100% (7)

- 12 I Denti Della TigreDocument398 pages12 I Denti Della TigreGiovanni ScognamiglioNo ratings yet

- Analyses With Identical Measures of Giving and Receiving SupportDocument2 pagesAnalyses With Identical Measures of Giving and Receiving SupportRoshaanNo ratings yet

- Running Head: REGRESSION ANALYSIS 1Document7 pagesRunning Head: REGRESSION ANALYSIS 1Brian JerryNo ratings yet

- Representation of The Market Mechanism of Income Distribution Using Lorenz Curve. Gini Coefficient.Document8 pagesRepresentation of The Market Mechanism of Income Distribution Using Lorenz Curve. Gini Coefficient.Мария МариничNo ratings yet

- CH 3 Statistical EstimationDocument13 pagesCH 3 Statistical EstimationManchilot Tilahun100% (1)

- Seismic Hazard Exposure: Social Indicators Risk IndicatorsDocument2 pagesSeismic Hazard Exposure: Social Indicators Risk IndicatorsSMPC Lagoa Luis VenturaNo ratings yet

- Networks of QueuesDocument11 pagesNetworks of QueuesEdina Kovačević KlačarNo ratings yet

- 1.4.4.aHVA NATURAL HAZARD FixDocument2 pages1.4.4.aHVA NATURAL HAZARD Fixdita mardianiNo ratings yet

- 2020 MexicoDocument2 pages2020 MexicoMartha MagallanesNo ratings yet

- 14 DidDocument22 pages14 DidGing lonmnNo ratings yet

- Measurement of Index of Refraction Using SnellDocument5 pagesMeasurement of Index of Refraction Using SnellIzdihar JohariNo ratings yet

- Pages extraites de dahlquist1986 اعجبني الموضوعDocument1 pagePages extraites de dahlquist1986 اعجبني الموضوعMohamed BelhadefNo ratings yet

- Safety Performance PT DNX - LMO W33Document26 pagesSafety Performance PT DNX - LMO W33Eva LaveniaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 - The Normal DistributionDocument21 pagesLecture 6 - The Normal DistributionJoshua KwekaNo ratings yet

- Lect7 Math231Document29 pagesLect7 Math231Qasim RafiNo ratings yet

- BERARDI - Real Rates Expectted Inflation and Inflation Risk Premia Implicit in Nominal Bond YieldsDocument43 pagesBERARDI - Real Rates Expectted Inflation and Inflation Risk Premia Implicit in Nominal Bond Yieldssubro1No ratings yet

- Hsts423 Unit 4Document13 pagesHsts423 Unit 4Keith Tanyaradzwa MushiningaNo ratings yet

- HVA Untuk Public Health Feb 2022Document16 pagesHVA Untuk Public Health Feb 2022Puskesmas TallunglipuNo ratings yet

- Advanced Econometrics: Instructor: Kanika MahajanDocument36 pagesAdvanced Econometrics: Instructor: Kanika MahajanNaman KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- 7 OLS AssumptionsDocument37 pages7 OLS AssumptionsSaitejNo ratings yet

- Medical Image Steganography Using Nuclear Spin Generator 2020 StoyanovDocument12 pagesMedical Image Steganography Using Nuclear Spin Generator 2020 StoyanovSujithNo ratings yet

- Pearson's Moment of CorrelationDocument1 pagePearson's Moment of CorrelationStrat CostNo ratings yet

- Internal Forces M Internal Forces M: Peter Und Lochner Beratende Ingenieure F. BauwesenDocument12 pagesInternal Forces M Internal Forces M: Peter Und Lochner Beratende Ingenieure F. BauwesenRadger Teddy ManuelNo ratings yet

- Historical PML by Treatment Epoch October 2010Document12 pagesHistorical PML by Treatment Epoch October 2010MSDocumentsNo ratings yet

- HVA Untuk Public Health Feb 2022Document16 pagesHVA Untuk Public Health Feb 2022MelurNo ratings yet

- OutlookOnLife CodebookDocument421 pagesOutlookOnLife CodebookSanket VardhaveNo ratings yet

- Chapter Two: Statistical Estimation: Definition of Terms: Interval EstimateDocument15 pagesChapter Two: Statistical Estimation: Definition of Terms: Interval EstimatetemedebereNo ratings yet

- Prediction of The Epidemic Peak of Coronavirus Disease in Japan, 2020Document8 pagesPrediction of The Epidemic Peak of Coronavirus Disease in Japan, 2020Bern Jonathan SembiringNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 - FINANCIAL MGT 2Document11 pagesChapter 2 - FINANCIAL MGT 2Dan RyanNo ratings yet

- DisSpec HR PosterDocument1 pageDisSpec HR PosterferalaesNo ratings yet

- App Mining AlgorithmDocument17 pagesApp Mining AlgorithmBlockstackNo ratings yet

- MaanyaduaDocument1 pageMaanyaduaMaanya DuaNo ratings yet

- Free Udamped Vibration For MDOF SystemDocument3 pagesFree Udamped Vibration For MDOF SystemManar AshrafNo ratings yet

- Probability DistributionsDocument6 pagesProbability Distributionsrasha assafNo ratings yet

- ResultsDocument8 pagesResultsMohamed FarahatNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes #6: Correlation and Regression 6-1: Reading Assignment: Stay Current With The ReadingDocument55 pagesLecture Notes #6: Correlation and Regression 6-1: Reading Assignment: Stay Current With The Readingsivaranjani sivaranjaniNo ratings yet

- File 6Document64 pagesFile 6Sisay TadesseNo ratings yet

- Páginas Desdecorre17.09cartelessantorini-1Document1 pagePáginas Desdecorre17.09cartelessantorini-1LOLA CORZONo ratings yet

- Note That Any Differences With The Results Presented in The Article Are Due To Rounding ErrorDocument4 pagesNote That Any Differences With The Results Presented in The Article Are Due To Rounding Errorsarath6872No ratings yet

- Zombie, Influennza and Other DiseasesDocument16 pagesZombie, Influennza and Other Diseasessamy OlivaNo ratings yet

- Medical Center Hazard and Vulnerability Analysis: InstructionsDocument10 pagesMedical Center Hazard and Vulnerability Analysis: InstructionsSANITASI TUGUNo ratings yet

- RIsk Register Risk Response Plan - 2022Document5 pagesRIsk Register Risk Response Plan - 2022David MonicaNo ratings yet

- TallyDocument2 pagesTallyapi-518020510No ratings yet

- A Review of Software To Easily Plot Johnson-Neyman FiguresDocument9 pagesA Review of Software To Easily Plot Johnson-Neyman Figuresagoall93No ratings yet

- HVA Untuk Public Health Feb 2022Document16 pagesHVA Untuk Public Health Feb 2022Yuliana WatiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Statistics Estimation FinalDocument13 pagesChapter 2 Statistics Estimation FinalLeykunBerhanuNo ratings yet

- Hazard AnalysisDocument15 pagesHazard AnalysisAthil ShipateNo ratings yet

- From The Framingham Heart Study AF Risk Prediction: Enter Values HereDocument1 pageFrom The Framingham Heart Study AF Risk Prediction: Enter Values HererespiarikaNo ratings yet

- Poster Fesbe Sergio MirtesDocument1 pagePoster Fesbe Sergio MirtesMirtes PereiraNo ratings yet

- Economic Crisis and Social Protection in IndonesiaDocument15 pagesEconomic Crisis and Social Protection in IndonesiaAsian Development BankNo ratings yet

- Biopharm Exp 2 2Document7 pagesBiopharm Exp 2 2Hassan GulNo ratings yet

- The Lognormal Distribution: Univariate DistributionsDocument7 pagesThe Lognormal Distribution: Univariate Distributionsbig clapNo ratings yet

- I Í P C (IPC) E 2018: Inflación Mensual (%) Enero 2017-Enero 2018Document5 pagesI Í P C (IPC) E 2018: Inflación Mensual (%) Enero 2017-Enero 2018BrianNo ratings yet

- 3 Individual Use of Asthma Medications: Key PointsDocument10 pages3 Individual Use of Asthma Medications: Key PointsLancre witchNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 EstimationDocument62 pagesChapter 7 EstimationAnja GuerfalaNo ratings yet

- IC Risk Assessment Worksheet - Kangas-V2.1-Aug.2010 1Document4 pagesIC Risk Assessment Worksheet - Kangas-V2.1-Aug.2010 1Juon Vairzya AnggraeniNo ratings yet

- Decision SC - Sem2Document8 pagesDecision SC - Sem2Prateek SharmaNo ratings yet

- Lec33 MetropolisHastingsDocument66 pagesLec33 MetropolisHastingshu jackNo ratings yet

- Fokkens EPOS 2020 Chronic Rhinosinusitis How To Implement Current and New Treatment OptionsDocument22 pagesFokkens EPOS 2020 Chronic Rhinosinusitis How To Implement Current and New Treatment OptionsGiuseppe MeccarielloNo ratings yet

- Draft Bureau of Customs Order - Reward To Persons Instrumental in The Actual Collection of Additional RevenuesDocument9 pagesDraft Bureau of Customs Order - Reward To Persons Instrumental in The Actual Collection of Additional RevenuesPortCallsNo ratings yet

- Npad PGP2017-19Document3 pagesNpad PGP2017-19Nikhil BhattNo ratings yet

- Azure Stack HCI Partner FAQDocument10 pagesAzure Stack HCI Partner FAQabidouNo ratings yet

- A Holistic Perspective On Corporate Sustainability Drivers GIN 2012Document17 pagesA Holistic Perspective On Corporate Sustainability Drivers GIN 2012gksjjjlk dfhhjdsNo ratings yet

- Ang Ladlad V ComelecDocument22 pagesAng Ladlad V ComelecRuab PlosNo ratings yet

- BC-FOUN-ILT-ST-CMMI ResortDocument4 pagesBC-FOUN-ILT-ST-CMMI Resorteddie KNo ratings yet

- (CÔ PHÍ THỊ BÍCH NGỌC) EBOOK 300 CÂU NGỮ PHÁP TINH TÚY KÈM ĐÁP ÁN CHI TIẾT 130 TRANGDocument134 pages(CÔ PHÍ THỊ BÍCH NGỌC) EBOOK 300 CÂU NGỮ PHÁP TINH TÚY KÈM ĐÁP ÁN CHI TIẾT 130 TRANGnguyenhoang210922No ratings yet

- Arduino For Arduinians - Copyright PageDocument1 pageArduino For Arduinians - Copyright PageabdelbadiebekkoucheNo ratings yet

- Order of Photofraph2Document4 pagesOrder of Photofraph2Samuel BoatengNo ratings yet

- Rural Tourism in UkraineDocument4 pagesRural Tourism in UkraineАнастасія Вадимівна СандигаNo ratings yet

- Magis Registration Form: Application Form For Grade 6 & 9Document3 pagesMagis Registration Form: Application Form For Grade 6 & 9Khan AaghaNo ratings yet

- Hempel - RECOMMENDED PAINTING SPECIFICATIONS and MaintenanceDocument304 pagesHempel - RECOMMENDED PAINTING SPECIFICATIONS and MaintenanceFachreza AkbarNo ratings yet

- Tulipa Gesneriana and T. HybridsDocument19 pagesTulipa Gesneriana and T. HybridsDragan ItakoToNo ratings yet

- Pages From 2020-European - Semester - Country-Report-Romania - En-3Document20 pagesPages From 2020-European - Semester - Country-Report-Romania - En-3MNo ratings yet

- Future Real Conditional: Unit 8Document16 pagesFuture Real Conditional: Unit 8Yoncar Zarate SotoNo ratings yet

- (Shaykh Ibn Uthaymeen) Errors in Manhaj Occur Due To Underlying Errors in AqidahDocument1 page(Shaykh Ibn Uthaymeen) Errors in Manhaj Occur Due To Underlying Errors in AqidahChauAnhNo ratings yet

- VALUATIONDocument4 pagesVALUATIONganeshnale061No ratings yet

- Spoiler-Here Comes The Lady ChefDocument2 pagesSpoiler-Here Comes The Lady Chefeulea larkaroNo ratings yet

- Phenomenon Consultants: E/503, Borsali Apt Khanpur, Ahmedabad-380001 PH: 079-25600269Document2 pagesPhenomenon Consultants: E/503, Borsali Apt Khanpur, Ahmedabad-380001 PH: 079-25600269Murli MenonNo ratings yet

- Submitted in Partial Fulfillment For The Award of The Degree of MBA General 2020-2021Document26 pagesSubmitted in Partial Fulfillment For The Award of The Degree of MBA General 2020-2021Chirag JainNo ratings yet

- Odsp 2019 Scholars AgreementDocument5 pagesOdsp 2019 Scholars AgreementTaga Phase 7100% (1)

- Logic and Sets: Clast Mathematics CompetenciesDocument40 pagesLogic and Sets: Clast Mathematics CompetenciesmiyumiNo ratings yet

- 16ProjectCommunication PDFDocument1 page16ProjectCommunication PDFLeo DobreciNo ratings yet