Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Two Year Window: The New Science of Babies and Brains-And How It Could Revolutionize The Fight Against Poverty

The Two Year Window: The New Science of Babies and Brains-And How It Could Revolutionize The Fight Against Poverty

Uploaded by

ccarmogarciaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Two Year Window: The New Science of Babies and Brains-And How It Could Revolutionize The Fight Against Poverty

The Two Year Window: The New Science of Babies and Brains-And How It Could Revolutionize The Fight Against Poverty

Uploaded by

ccarmogarciaCopyright:

Available Formats

The Two Year Window

The new science of babies and brains—and how it could revolutionize the fight against poverty.

J o nat h a n C o h n

A

decade ago, a neuroscientist named Charles would be the removal from the institutions, allowing research-

Nelson traveled to Bucharest to visit Romania’s ers to isolate the effects of neglect on the brain.

infamous orphanages. There, he saw a child Prior to the project, investigators had observed that the or-

whose brain had swelled to the size of a basket- phans had a high frequency of serious developmental problems,

ball because of an untreated infection and a mal- from diminished IQs to extreme difficulty forming emotional

nourished one-year-old no bigger than a new- attachments. Meanwhile, imaging and other tests revealed that

born. But what has stayed with him ever since was the eerie some of the orphans had reduced activity in their brains. The

quiet of the infant wards. “It would be dead silent, all of [the Bucharest project confirmed that these findings were more

babies] sitting on their backs and staring at the ceiling,” says than random observations. It also uncovered a striking pat-

Nelson, who is now at Harvard. “Why cry when nobody is tern: Orphans who went to foster homes before their second

going to pay attention to you?” birthdays often recovered some of their abilities. Those who

Nelson had traveled to Romania to take part in a cutting-edge went to foster homes after that point rarely did.

experiment. It was ten years This past May, a team led by

after the fall of the Communist Stacy Drury of Tulane reported

dictator Nicolae Ceauşescu, a similar finding—with an in-

whose scheme for increasing the triguing twist. The researchers

country’s population through found that telomeres, which are

bans on birth control and abor- protective caps that sit on the

tion had filled state-run institu- ends of chromosomes, were

tions with children their parents shorter in children who had

couldn’t support. Images from spent more time in the Ro-

the orphanages had prompted manian orphanages. In theory,

an outpouring of international damage to the telomeres could

aid and a rush from parents change the timing of how some

around the world to adopt the cells develop, including those in

children. But ten years later, the brain—making the shorter

the new government remained telomeres a harbinger of future

convinced that the institutions mental difficulties. It was the

were a good idea—and was still clearest signal yet that neglect

warehousing at least 60,000 kids, of very young children does not

some of them born after the old merely stunt their emotional

regime’s fall, in facilities where development. It changes the ar-

many received almost no mean- chitecture of their brains.

ingful human interaction. With Drury, Nelson, and their

backing from the MacArthur In Romania’s infamous orphanages, many children received collaborators are still learning

Foundation, and help from a almost no meaningful human interaction. about the orphans. But one

sympathetic Romanian official, upshot of their work is already

Nelson and colleagues from clear. Childhood adversity can

Harvard, Tulane, and the University of Maryland prevailed upon damage the brain as surely as inhaling toxic substances or ab-

the government to allow them to remove some of the children sorbing a blow to the head can. And after the age of two, much

from the orphanages and place them with foster families. Then, of that damage can be difficult to repair, even for children who

the researchers would observe how they fared over time in com- go on to receive the nurturing they were denied in their early

parison with the children still in the orphanages. They would years. This is a revelation with profound implications—and not

also track a third set of children, who were with their original just for the Romanian orphans.

parents, as a control group.

A

In the field of child development, this study—now known pproximately seven million American infants,

Mashid Mohadjerin/Redux

as the Bucharest Early Intervention Project—was nearly un- toddlers, and preschoolers get care from somebody

precedented. Most such research is performed on animals, other than a relative, whether through organized day

because it would be unethical to expose human subjects to ne- care centers or more informal arrangements, according to the

glect or abuse. But here the investigators were taking a group Census Bureau. And much of that care is not very good. One

of children out of danger. The orphanages, moreover, provided widely cited study of child care in four states, by researchers in

a sufficiently large sample of kids, all from the same place and Colorado, found that only 8 percent of infant care centers were

all raised in the same miserable conditions. The only variable of “good” or “excellent” quality, while 40 percent were “poor.”

10 D e c e mbe r 1 , 2 0 1 1 The Ne w R e publ ic

The National Institute of Child Health we invest the least. According to research business as usual. And if this happens re-

and Human Development has found that by the Urban Institute and the Brookings peatedly, as it should, the nerve impulses

three in four infant caregivers provide Institution, children get about half as crackling in the brain will carry the sig-

only minimal cognitive and language many taxpayer resources, per person, as nals for effective coping with stress over

stimulation—and that more than half do the elderly. And among children, the and over again—building pathways that

of young children in non-maternal care youngest get the least. The annual federal the baby can use later in life to solve

receive “only some” or “hardly any” pos- investment in elementary school kids ap- problems and overcome difficulty.

itive caregiving. proaches $11,000 per child. For infants But the baby who is ignored or ne-

Of course, children in substandard day and toddlers up to age two, it is just over glected just keeps screaming and flail-

care are not the only children at risk in $4,000. When it comes to early childhood, ing. Eventually, he exhausts himself and

the United States. There are also hun- public policy is lagging far behind sci- may appear to withdraw. Yet the quiet

dreds of thousands of babies born each ence—with disastrous consequences. child is not a content child. Constant ac-

year to American teenagers, about 60 tivation of the stress system causes wear

T

percent of them poor. The vast majority h e a du lt br a i n consists of and tear on the brain, altering the forma-

of teen mothers are unmarried when they about a hundred billion nerve cells, tion of neural pathways, so that coping

give birth, and frequently lack either fam- or neurons, that communicate with and thinking mechanisms don’t develop

ily support or the financial resources to each other and the rest of the body by in the same way. For example, a baby

find capable outside help. Then there are transmitting electrical impulses. A baby’s who endures prolonged abuse or ne-

the children who begin their lives in trau- genes contain a blueprint for what cells glect is likely to end up with an enlarged

matic circumstances for other reasons— to build and when, and how those cells amygdala: a part of the brain that helps

because they have a parent with clinical are capable of operating, over the course generate the fear response.

depression, or they witness violence in the of a lifetime. But experience and environ- Some of the earliest and most impor-

home. Nobody has a precise definition of ment have profound effects on how the tant research establishing this process

adversity, let alone a number for the chil- body reads and applies that blueprint. dates to the 1950s, when investigators

dren who experience it. But experts like Hormones affect this process, espe- observed that rats were better at solv-

Nelson think at least a few hundred thou- cially stress hormones. Like all living ing problems if they got more nurturing

sand children suffer from serious abuse or creatures, human babies are hard-wired at very young ages. Among the pioneer-

neglect every year. Presumably they are with a stress reaction. It’s a survival ing scientists in this field were Seymour

disproportionately, although far from ex- mechanism that, millions of years ago, Levine of Stanford, Michael Meaney of

clusively, in low-income families. McGill, and Bruce McEwen of Rocke-

For a long time, social science has feller University. McEwen’s work showed,

known of correlations between childhood among other things, that persistently high

turmoil and all sorts of adult maladies that The science of early levels of cortisol altered the structure of

carry massive social and financial costs— childhood may play the hippocampus, a part of the brain that

mental illness, addiction, tendencies to-

ward violence. And for decades, we have a significant role plays a key role in forming memories

and providing context for emotional re-

attempted to address those problems with in the political actions. Eventually McEwen introduced

a variety of social interventions: Head

Start, which aims to prepare low-income

question of our time: a term, “allostatic load,” to describe what

was happening when stress hormones in-

kids between the ages of three and five rising inequality. undated the body for extended periods of

for school; investments in elementary and time. Subsequent research showed that

high school children; programs for reha- persistent childhood stress also leads to

bilitation of juvenile delinquents. While allowed humans to protect themselves significant physical problems, such as far

some have achieved important successes, from hunger, cold, or a saber-toothed higher rates of cardiovascular disease and

many of the problems stemming from tiger about to pounce. Today, that stress diabetes, as Paul Tough explained in an

childhood poverty remain intractable. response kicks in whenever a baby per- elegant New Yorker article in March.

But a scientific revolution that has ceives a threat, which can be as simple But the links to cognitive and intel-

taken place in the last decade or so illu- as hunger or the feeling of a wet diaper. lectual problems are just as concrete.

minates a different way to address the Deep inside the adrenal glands, which sit Early adversity, says Nelson, can inter-

dysfunctions associated with childhood atop the kidneys, cells pump out adren- fere with “planning ability, cognitive flex-

hardship. This science suggests that many aline—a hormone that makes the lungs ibility, problems with memory, and all

of these problems have roots earlier than breathe and the heart beat faster, increas- of those will correlate with diminished

is commonly understood—especially dur- ing the supply of oxygen to the muscles. IQ.” Every one of the researchers empha-

ing the first two years of life. Researchers, In the outer shell of the glands, different sizes that some children who go through

including those of the Bucharest project, cells produce cortisol, which helps the these experiences end up OK—and that

have shown how adversity during this pe- body devour stored sugars and prepare later interventions may still be helpful for

riod affects the brain, down to the level the immune system to ward off invaders. those children who struggle. But, over-

of DNA—establishing for the first time a With these hormones sloshing around, all, says Nelson, “they’re more likely to

causal connection between trouble in very blood pressure rises, muscles tighten, and have mental health problems. The top

early childhood and later in life. And they energy surges. A baby wails, waiting for of the list will be anxiety. Second to that

have also shown a way to prevent some of somebody to provide milk, dry clothing, will be attention deficit disorder. And

these problems—if action is taken during or maybe just a warm embrace. When then depression.” One 2010 paper from

those crucial first two years. comfort comes quickly, the body pro- Psychological Medicine concluded that

The first two years, however, happen duces fewer stress hormones, the baby “childhood adversities”—a category that

to be the period of a child’s life in which calms down, and the brain goes back to includes abusive parenting and economic

The New R epubl ic D ece mber 1 , 2 011 11

hardship—were associated with about It also operates its own child care center the background. Like most of the young

one in five cases of “severely impairing” and school, called Educare, that became mothers Caref visits, Rosaria came to

mental disorders and about one in four the model for a national network of such Christopher House via a referral (in this

anxiety disorders in adulthood. facilities designed to improve day care case, from a health clinic) while she was

These problems incur large costs. Think for infants and young children, including pregnant. The official agenda for the visit

about the lost wages from serious mental those too young for Head Start. But per- was to assess whether she was still work-

health problems, which total $200 billion haps the program’s most intriguing initia- ing toward her own goals as a student

a year, according to a 2008 study from the tive is its work with agencies that provide and as a parent. But, as always, it was

American Journal of Psychiatry. Or think at-home visits to young women, particu- also a chance to check up on the baby

about the expense of incarcerating crim- larly teenagers, who are either pregnant and how Rosaria was caring for him.

inals: about $60 billion a year, according or are new mothers. Some of these agen- Rosaria told Caref she was pleased that

to a 2006 study from the Commission on cies employ doulas, who are specially- her boy was aware of her voice and would

Safety and Abuse in America’s Prisons. trained to provide advice and support to turn his head to follow her. “He laughs

Childhood adversity obviously doesn’t mothers, from the prenatal period all the all the time; he’s smiling,” she said. When

account for all of these sums. But if the way up through early childhood. Caref pulled out a rattle, it got his atten-

studies are correct, then adversity ex- A few weeks ago, I went on a visit tion right away. “Curioso,” Rosaria said,

plains a significant portion—certainly in with Maria Caref, a doula who works “like Curious George.” At that point, Ro-

the tens of billions of dollars. for Christopher House, an organization saria pointed out a plaything she’d made

And the implications go beyond men- that partners with Ounce of Prevention. the baby, by sewing buttons onto socks

tal illness or crime. Children who fail Maria was visiting Rosaria, a 17-year-old that she’d turned into mittens. Caref

to develop coping mechanisms strug- high school student with a four-month- smiled but, after tugging on the buttons

gle from the earliest days in school, be- old baby boy. (As a condition of my at- with her fingers, warned that they were ac-

cause even the slightest provocations or tendance, I agreed not to identify the real tually a hazard: “Wow, mom is so creative,”

setbacks destroy their focus and atten- name of Rosaria or her baby.) Caref cooed, while holding the baby. “But

tion. They can’t sit still and read. They Rosaria lives on the second floor of a you have to be careful,” she said, carefully

have trouble standing in line. They lash house in a lower-income, predominantly switching gears. “He can pull this hard

out at classmates or teachers. And these Latino neighborhood on the west side. and he can swallow this. It would be very

struggles, naturally, lead to other prob- When we walked in, her son was lying dangerous.” Later the two talked about

lems that perpetuate the cycle of pov- face-up on a Winnie-the-Pooh fleece whether Rosaria had followed up with

erty. All of this is to say that the science blanket on the floor, playing with a ball. immunizations (she had) and whether she

of early childhood may play a significant Rosaria was on the floor next to him. was still reading to the boy regularly (she

role in the dominant political question of Children’s music was playing loudly in was, although not as regularly as before

our time: rising inequality.

T

he first time I heard of this field

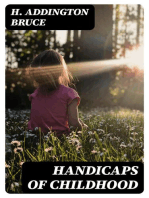

of research was during a conversa- Childhood Adversity: Inside the Brain

tion with a woman named Diana

Rauner. In the early ’90s, about a decade

after graduating from Yale, Rauner had

Remained in Placed in

left a lucrative career in private equity to Orphanage Foster Care

study developmental psychology at the After 24 Months

University of Chicago. For her disserta-

tion, she visited day care centers in the

city, hoping to learn about how infants

and toddlers pick up language skills. But

she learned a lot more about the sorry

state of child care. Rauner described fa-

cilities where infants were strapped in

car seats, “watching The Lion King all

day,” while the older kids were “circling

the room almost like sharks” and throw- Placed in Never

Foster Care Institutionalized

ing things at the infants, because they had Before 24

nothing else to do. But the infants fre- Months

quently didn’t cry. “A lot would just stare,

which is almost worse,” Rauner says.

Today, Rauner runs a nonprofit orga-

nization called the Ounce of Prevention

Fund, a $40 million-per-year initiative

that applies the latest scientific find-

ings about early childhood—in particu-

2010 Vanderwert et al.

lar, those first few years—to help some This figure from a 2010 study shows electrical activity in the brains of eight-year-old

of Chicago’s most disadvantaged fami- children involved in the Bucharest Early Intervention Project. These patterns show that

lies. The fund trains workers at day care children removed from orphanages before the age of two developed brain activity similar

centers on how to nurture babies in ways to children who were never institutionalized, while the brain patterns of children removed

that will stimulate positive brain activity. after the age of two were similar to those of children who remained in the orphanages.

12 D e c e mbe r 1 , 2 0 1 1 The Ne w R e publ ic

because she was busy with her own home- is much more compelling than the con- childhood care is probably declining,

work). “For some mothers, it’s really hard cept that poverty is bad for your health,” given how much of it flows through cash-

to keep up,” Caref told Rosaria as we left. says Jack Shonkoff, a Harvard pedia- strapped state governments that are fran-

“You’ve been doing really well.” trician and chair of the National Scien- tically cutting their budgets. In Illinois, to

A major goal of these visits is to estab- tific Council on the Developing Child. “It give just one example, about 5,000 at-risk

lish long-term relationships, so that the gives us a basis for developing new ideas, children will lose state-financed school-

young women come to see the visitors for going into policy areas, given what ing, care, or developmental services this

as both a source of support and an advo- we know, and saying here are some new year because of a 5 percent budget cut,

cate for their interests. Visitors like Caref strategies worth trying.” according to Adam Summers, from Illi-

are trained to deal with a wide range of nois Action for Children. And that’s in ad-

A

issues, from basic psychology to health. fter m y v isit with Caref, it dition to 14,000 kids who lost access to

During the visit, Caref talked to Rosaria was possible to imagine what a state-funded pre-kindergarten in the last

about breastfeeding, which has signifi- comprehensive policy response two years. At the federal level, House Re-

cant health benefits for both mother and to the problems of impoverished early publicans have proposed eliminating the

daughter. They also spoke about birth childhood might look like. Young fami- new home visit funds altogether.

control. Studies have shown that teen lies would have the option of home vis- Hard times require hard choices, of

mothers who have more than one child, its, from doulas or social workers. Child course. But these cuts can be counter-

particularly in rapid succession, are by care would be higher quality across the productive. One of the most convinc-

far the most likely to fall into crisis. board. It would also be affordable, even ing advocates for this argument is James

The model for these efforts is a visiting for families at or below the poverty line. Heckman, a Nobel Prizewinning econo-

nurse program that David Olds, a Uni- Such services wouldn’t be available ex- mist from the University of Chicago. Ear-

versity of Colorado pediatrician, tested clusively to the poor, since middle-class lier in his career, Heckman undertook a

in Elmira, New York, during the ’70s and families could also benefit from many of project to study the effects of high school

’80s, and which grew into the national these programs. That would make them equivalency (GED) programs. To his cha-

Nurse-Family Partnership. In 2011, the more popular, too. grin, he discovered that the graduates

program, which the federal government From a policy standpoint, probably the didn’t seem to be much better off, de-

helps finance, will serve more than 20,000 spite the considerable public investment

families; they receive home nurse visits in the programs. So Heckman began a

from when they become pregnant until Children get about quest to discover what kinds of govern-

their children are two years old. Olds’s

program is one of the more unambigu-

half as many taxpayer ment spending would work. His research

led him to the conclusion that earlier is

ous success stories in the modern history resources, per person, better, until eventually he came to focus

of social policy. Two long-term studies

published in the Journal of the Ameri-

as do the elderly. on the first years of a child’s life.

Heckman argues that a dollar spent on

can Medical Association found that ad- the earliest years of life generates more

olescents whose mothers had been in biggest question about home visiting is payoff than a dollar spent on later child-

the program were less likely to run away, how well it would work on a much larger hood—let alone a dollar spent on adult-

get arrested, or consume alcohol or to- scale. Not all home programs are going to hood. Neither he nor any of the scientific

bacco. Reports of child abuse were lower be as thorough as the effort I saw in Chi- researchers believes the United States

by about 50 percent. cago, which means they may not produce should stop funding later interventions

When the rand Institute evaluated the the same benefits. This is a familiar prob- as long as the programs actually have

initiative, it determined that the program lem: Studies of Head Start, for example, some impact. Among other things, plenty

would save between $1.26 and $5.70 for suggest that it does not have the long-last- of infants with nurturing caregivers still

every $1 spent, with the higher savings ing effects on test scores that exemplary develop problems later on, for other rea-

from the higher-risk families, thanks to programs like the famous Perry Preschool sons. But Heckman agrees with research-

reduced spending on hospitals, incarcer- in Ypsilanti, Michigan, do. Instead, Head ers who argue that the older the child, the

ation, and cash assistance. And accord- Start’s impact on test scores tends to fade more expensive and difficult those inter-

ing to Timothy Bartik, an economist and (although many researchers argue plau- ventions will be.

author of Investing in Kids, every dollar sibly that dismal assessments of reading Heckman has tried to make this case

that goes into the Nurse-Family Part- or math skills overlook other advantages to anybody who will listen, including

nership will raise incomes for the entire that Head Start students gain). members of the congressional super

population by $1.85, once you factor the But the bigger questions right now are committee on deficit reduction, whose

economic benefits of a more productive political. Nobody is talking about launch- cuts to social services—either directly or

workforce—and a tax base that won’t be ing a new government initiative, no mat- through reduced aid to the states—could

so strained picking up the tab for reme- ter how much money it might save in the decimate existing services while leaving

diation and crime. High-functioning day long run. On the contrary, the focus today little room for new initiatives. “We can

care centers that cover birth through age is on slashing government spending. The gain money by investing early to close

five, Bartik says, produce a larger payoff Affordable Care Act has $1.5 billion over disparities and prevent achievement

per dollar: $2.25. five years for expanding visiting nurse gaps, or we can continue to drive up def-

The science of early adversity, then, of- programs for brand new mothers. That’s icit spending by paying to remediate dis-

fers a blueprint for tackling the effects of a massive expansion over the previous in- parities when they are harder and more

poverty and neglect, one that is more pre- vestment which, according to administra- expensive to close,” Heckman wrote in a

cise and observable than any tools poli- tion officials, was only in the millions. But formal letter to the committee in Sep-

cymakers have ever had at their disposal. even as that money works its way through tember. “The argument is very clear from

“The concept of disrupting brain circuitry the pipeline, the net investment in early an economic standpoint.” d

The New R epubl ic D ece mber 1 , 2 011 13

Copyright of New Republic is the property of TNR II, LLC and its content may not be copied or emailed to

multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users

may print, download, or email articles for individual use.

You might also like

- God Grades and Graduation Religions Surprising Impact On Academic Success Ilana M Horwitz Full ChapterDocument67 pagesGod Grades and Graduation Religions Surprising Impact On Academic Success Ilana M Horwitz Full Chapterbarbara.kohn126100% (5)

- Enhanced Erpat ManualDocument167 pagesEnhanced Erpat ManualNeil Sabijon88% (42)

- Becoming Attached PDFDocument18 pagesBecoming Attached PDFRoberto Montaño100% (4)

- PD Lesson 4 Challenges of Middle and Late AdolescenceDocument20 pagesPD Lesson 4 Challenges of Middle and Late AdolescenceEL Fuentes100% (2)

- Adolescent Sleep PatternsDocument319 pagesAdolescent Sleep PatternsHaning Tyas Cahya Pratama100% (1)

- The Difference Between Being Smart, Educated, and Intelligent by Gian Fiero PDFDocument9 pagesThe Difference Between Being Smart, Educated, and Intelligent by Gian Fiero PDFPhil Engel100% (1)

- Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society American ScientistDocument9 pagesSigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society American ScientistLuis CortesNo ratings yet

- Berens 2015Document11 pagesBerens 2015Karen CárcamoNo ratings yet

- Romania's Abandoned Children: Deprivation, Brain Development, and the Struggle for RecoveryFrom EverandRomania's Abandoned Children: Deprivation, Brain Development, and the Struggle for RecoveryRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Half-Baked Teen Brain: A Hazard or A Virtue?: Maia SzalavitzDocument2 pagesThe Half-Baked Teen Brain: A Hazard or A Virtue?: Maia SzalavitzNiftyNo ratings yet

- Review: Anne E Berens, Charles A NelsonDocument12 pagesReview: Anne E Berens, Charles A NelsonMarina Sánchez PicazoNo ratings yet

- OverimitationDocument9 pagesOverimitationJúlia FerrazNo ratings yet

- Psychedelic Family ValuesDocument6 pagesPsychedelic Family ValuesΧρήστος Παναγιώτης ΧατζηκώσταςNo ratings yet

- The Science of Early Adversity Charles NelsonDocument11 pagesThe Science of Early Adversity Charles NelsonMatias Reyes CamposNo ratings yet

- What Is Human Cloning?Document10 pagesWhat Is Human Cloning?OwethuNo ratings yet

- 20 Brain TrustDocument6 pages20 Brain TrusttomcorreaNo ratings yet

- Wynn, Hamlin - 2010 - The Moral Life of BabiesDocument16 pagesWynn, Hamlin - 2010 - The Moral Life of BabiesMauricio Vega MontoyaNo ratings yet

- Eng ConsDocument4 pagesEng ConsReillah DeluriaNo ratings yet

- Bruner, Jerome - The Growth of MindDocument11 pagesBruner, Jerome - The Growth of MindTalia Tijero100% (1)

- Human Cloning Ethical Issues 864 0814Document2 pagesHuman Cloning Ethical Issues 864 0814Arslan AliNo ratings yet

- Research Papers On Crack BabiesDocument4 pagesResearch Papers On Crack Babiesjuzel0zupis3100% (1)

- Thesis Human CloningDocument5 pagesThesis Human Cloningybkpdsgig100% (2)

- Orchid ChildrenDocument10 pagesOrchid ChildrenAndie LurveNo ratings yet

- 2.2 Can Down Syndrome Be TreatedDocument4 pages2.2 Can Down Syndrome Be TreatedLina LoveraNo ratings yet

- Term Paper On EugenicsDocument7 pagesTerm Paper On Eugenicsafmzydxcnojakg100% (1)

- C - Infantparent Cosleeping in An Evolutionary Perspective Implicati 1993Document20 pagesC - Infantparent Cosleeping in An Evolutionary Perspective Implicati 1993hannanatalilustNo ratings yet

- Thesis Statement On Genetic CloningDocument4 pagesThesis Statement On Genetic Cloningmaggiecavanaughmadison100% (2)

- Poverty and Its Effect On Infant Development.Document3 pagesPoverty and Its Effect On Infant Development.Flaviah KamandaNo ratings yet

- ASD EtiologyDocument21 pagesASD EtiologyJulia HartNo ratings yet

- The Best Pro-Life Arguments: For Secular AudiencesDocument40 pagesThe Best Pro-Life Arguments: For Secular AudiencesAlvin John SumayloNo ratings yet

- Peter H. Kahn, Stephen R. Kellert - Children and Nature - Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary investigations-MIT Press (2002)Document371 pagesPeter H. Kahn, Stephen R. Kellert - Children and Nature - Psychological, Sociocultural, and Evolutionary investigations-MIT Press (2002)Víctor FuentesNo ratings yet

- New Perspectives On The Management of IntersexDocument1 pageNew Perspectives On The Management of Intersexmompou88No ratings yet

- 09: The Nature/Nurture Debate: Student ObjectivesDocument8 pages09: The Nature/Nurture Debate: Student ObjectivesŞterbeţ RuxandraNo ratings yet

- Lost Child in The Woods - EditedDocument6 pagesLost Child in The Woods - EditedMOSES ONG'ERANo ratings yet

- Special Section: Cloning: Technology, Policy, and EthicsDocument5 pagesSpecial Section: Cloning: Technology, Policy, and EthicsRami NaNo ratings yet

- Human Cloning Ethical Issues LeafletDocument2 pagesHuman Cloning Ethical Issues Leafletbenieo96No ratings yet

- Parenting Tips From MontessoriDocument52 pagesParenting Tips From Montessorintmurphy100% (4)

- FULL Download Ebook PDF Interventions With Children and Youth in Canada 2nd Edition by Maureen Cech PDF EbookDocument41 pagesFULL Download Ebook PDF Interventions With Children and Youth in Canada 2nd Edition by Maureen Cech PDF Ebookmichael.longoria496100% (38)

- Sapolsky - 8. Recognizing RelativesDocument3 pagesSapolsky - 8. Recognizing Relativesmama doloresNo ratings yet

- Alarcon y Nauhuelcheo - Creencias Sobre El Embarazo, Parto y Puerperio en La Mujer MapucheDocument15 pagesAlarcon y Nauhuelcheo - Creencias Sobre El Embarazo, Parto y Puerperio en La Mujer MapuchePablo HerrazNo ratings yet

- Giedd 2015 The Amazing Teen BrainDocument8 pagesGiedd 2015 The Amazing Teen BrainJesus GuillenNo ratings yet

- Cloning: Cloning Describes The ProcessDocument1 pageCloning: Cloning Describes The ProcessCristina GăvănescuNo ratings yet

- The Question of Nature VsDocument3 pagesThe Question of Nature VssimonroigNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 Sid GardnerDocument8 pagesChapter 1 Sid GardnerfisiodoulaerikaNo ratings yet

- By Brenna Lewis, SFLA Staff Writer: Pro-Abortion, Anti-ScienceDocument3 pagesBy Brenna Lewis, SFLA Staff Writer: Pro-Abortion, Anti-ScienceBrenna LewisNo ratings yet

- An Evolutionary Perspective On Night TerrorsDocument6 pagesAn Evolutionary Perspective On Night TerrorssiralkNo ratings yet

- Autism Spectrum Disorder: A Concept in Evolution: CME ArticleDocument7 pagesAutism Spectrum Disorder: A Concept in Evolution: CME ArticleMónicaNo ratings yet

- Avoiding The Sequela Associated With Deformational PlagiocephalyDocument8 pagesAvoiding The Sequela Associated With Deformational PlagiocephalychiaraNo ratings yet

- Cloning 1Document2 pagesCloning 1parthiv22191No ratings yet

- Babies in Boxes and The Missing Links On Safe Sleep: Human Evolution and Cultural RevolutionDocument7 pagesBabies in Boxes and The Missing Links On Safe Sleep: Human Evolution and Cultural RevolutionZachNo ratings yet

- Were You Born That Way? PDFDocument6 pagesWere You Born That Way? PDFChristina ZhangNo ratings yet

- Disorganized Attachment in Early Childhood: Meta-Analysis of Precursors, Concomitants, and SequelaeDocument25 pagesDisorganized Attachment in Early Childhood: Meta-Analysis of Precursors, Concomitants, and SequelaeGabe MartindaleNo ratings yet

- Human Cloning Research Paper ThesisDocument7 pagesHuman Cloning Research Paper Thesismariestarsnorthlasvegas100% (2)

- Human CloningDocument14 pagesHuman CloningKuvin RajNo ratings yet

- The Moral Life of Babies: MagazineDocument24 pagesThe Moral Life of Babies: MagazineLodenMaloneNo ratings yet

- Dwarfism Essays Research PapersDocument8 pagesDwarfism Essays Research Papersljkwfwgkf100% (1)

- The Art of Waiting by Belle BoggsDocument7 pagesThe Art of Waiting by Belle BoggssimasNo ratings yet

- Human Cloning: A Social Ethics PerspectiveDocument4 pagesHuman Cloning: A Social Ethics PerspectiveJecel Jean Gaudicos GabatoNo ratings yet

- Anguish of The Abandoned ChildDocument6 pagesAnguish of The Abandoned ChildMichael GobacoNo ratings yet

- The Premenstrual Syndrome and The Partner RelationshipDocument8 pagesThe Premenstrual Syndrome and The Partner RelationshipccarmogarciaNo ratings yet

- Egger Angold 2006emot Behav Problems in PreschoolerDocument25 pagesEgger Angold 2006emot Behav Problems in PreschoolerccarmogarciaNo ratings yet

- Poulou 2015Document12 pagesPoulou 2015ccarmogarciaNo ratings yet

- German Psychosomatics 2018Document11 pagesGerman Psychosomatics 2018ccarmogarciaNo ratings yet

- My Parenting Dna MHDocument4 pagesMy Parenting Dna MHapi-556623699No ratings yet

- HRM-F-65 Nepotism CertificateDocument1 pageHRM-F-65 Nepotism CertificateNew movie starNo ratings yet

- Placenta Previa PathoDocument2 pagesPlacenta Previa Pathoshakira0% (1)

- Tiger Parenting Essay CorrectionDocument2 pagesTiger Parenting Essay Correction11B 04 CHEN Ka YeeNo ratings yet

- WHO Curriculum Matrix For CSE in EuropeDocument15 pagesWHO Curriculum Matrix For CSE in EuropeTácio Lorran100% (1)

- Assignment: Societal Factors and Behaviour Maladjustment of The Boy-Child Student Name: Student IDDocument16 pagesAssignment: Societal Factors and Behaviour Maladjustment of The Boy-Child Student Name: Student IDSummaiyya FazalNo ratings yet

- Who Hep Nfs 21.24 EngDocument29 pagesWho Hep Nfs 21.24 EngIan CeeNo ratings yet

- Mentalization-Based Psychotherapy Interventions With Mothers-to-BeDocument6 pagesMentalization-Based Psychotherapy Interventions With Mothers-to-BePaz LanchoNo ratings yet

- Session 17 HIV OverviewDocument20 pagesSession 17 HIV Overviewapi-19824701No ratings yet

- Jurnal Aroma TerapiDocument3 pagesJurnal Aroma TerapidewiNo ratings yet

- A Poem by A Student of Green Hill AcademyDocument3 pagesA Poem by A Student of Green Hill AcademyJean-Louis KayitenkoreNo ratings yet

- Your Family Tree: In-LawsDocument4 pagesYour Family Tree: In-LawszorzicaNo ratings yet

- Dulcan's Textbook of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Edited by Mina K. Dulcan, M.D.Document875 pagesDulcan's Textbook of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Edited by Mina K. Dulcan, M.D.farhanNo ratings yet

- Module 1 NCM 107 Pedia G & DDocument18 pagesModule 1 NCM 107 Pedia G & DAshley Nicole Bulawan BalladNo ratings yet

- Parenting Stress Index-7-11Document5 pagesParenting Stress Index-7-11asdigistore101No ratings yet

- Parents' Involvement in Modular Distance Learning and The Academic Performance of Grade 6 Learners in A Public SchoolDocument11 pagesParents' Involvement in Modular Distance Learning and The Academic Performance of Grade 6 Learners in A Public SchoolGERALD QUIBANNo ratings yet

- Set Your Family Free Breaking Satan's Assignments Against Your Household (PDFDrive)Document168 pagesSet Your Family Free Breaking Satan's Assignments Against Your Household (PDFDrive)chille28No ratings yet

- FC PROJECTDocument15 pagesFC PROJECTJainam Mody100% (3)

- Affidavit of Intent & ConsentDocument5 pagesAffidavit of Intent & ConsentjomelNo ratings yet

- Cultural Alienation: A Comparative Commentary in "No Speak English" and "Crickets"Document2 pagesCultural Alienation: A Comparative Commentary in "No Speak English" and "Crickets"Florencia MontoyaNo ratings yet

- Wolf ChildrenDocument7 pagesWolf ChildrenYol MagayonNo ratings yet

- Roles and Function of The Nurse in Varied Settings in The Delivery of Care To at Risk Mother and ChildDocument2 pagesRoles and Function of The Nurse in Varied Settings in The Delivery of Care To at Risk Mother and Child049530No ratings yet

- Proposals: Makerere University School of Public Health List of Newly Submitted Proposals and Concepts - March 27, 2023Document5 pagesProposals: Makerere University School of Public Health List of Newly Submitted Proposals and Concepts - March 27, 2023kihembo pamelahNo ratings yet

- Q2-COT-LP - Health8 (Importance of Responsible Parenthood)Document6 pagesQ2-COT-LP - Health8 (Importance of Responsible Parenthood)chris annNo ratings yet

- Personal Diversity Narrative: Janna Krutz Human Diversity January 24.2022Document4 pagesPersonal Diversity Narrative: Janna Krutz Human Diversity January 24.2022janna krutzNo ratings yet

- O BGYNDocument84 pagesO BGYNselvie87100% (2)

- Dissertation L AdoptionDocument9 pagesDissertation L AdoptionWriteMyStatisticsPaperUK100% (1)