Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Based Assessment Top Down and Bottom Up

Uploaded by

jesscavalcanteOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Based Assessment Top Down and Bottom Up

Uploaded by

jesscavalcanteCopyright:

Available Formats

The Issue Is

Implementing Occupation-Based Assessment

Clare Hocking argued, therapists’ attention can become

I

n the early 1990s, occupational ther-

apists were challenged to refocus diverted from the person who has the

their evaluation processes. Specifical- condition to the medical condition itself.

Clare Hocking, MHSc(OT), is Principal

ly, they were urged to focus on their In addition, evaluations that focus on

Lecturer, School of Occupational Therapy,

clients’ abilities to do what they want performance components are unlikely to

Auckland University of Technology, Private

and need to do and to carry out mean- reveal clients’ capabilities and adaptive

Bag 92 006, Auckland, New Zealand;

ingful occupation rather than evaluating strategies or to contribute to understand-

clare.hocking@aut.ac.nz.

the components underlying occupational ing the interaction between people and

performance problems (Fisher, 1992a, their environments (Mathiowetz, 1993).

This article was reviewed and accepted

1994a; Law et al., 1994; Mathiowetz, for publication February 4, 2001, by

Overall, a consensus seems to be

1993; Trombly, 1993). Subsequently, the M. Carolyn Baum, developing that evaluations that focus

call for occupation-based assessment has previous Associate Editor, The Issue Is. directly on occupation are most true to

been repeated and amplified (cf., Baum the basic concepts of occupational thera-

& Law, 1997; Coster, 1998). py (Coster, 1998; Fisher, 1992a; Gillette,

Several compelling rationales for aspect of a client’s performance to mea- 1991; Trombly, 1993). The complexities

this refocusing have been offered. First, sure. Until recently, occupational thera- of implementing occupation-based

evaluations that do not focus on the pists assumed that a strong correlation assessments, however, have received little

occupations that clients find problematic exists between performance components attention.

will not communicate the purpose of and occupational performance. Based on This article suggests that conceptu-

occupational therapy to clients or col- this assumption, evaluation of the com- alizing occupation in terms of meaning,

leagues and, thus, will contribute to con- ponents that underpin performance function, form, and performance com-

fusion and dissatisfaction with occupa- appeared to provide a good basis for ponents may provide a useful framework

tional therapy services (Fisher & Short- intervention. A growing body of research, to guide clinical reasoning about what to

DeGraff, 1993; Trombly, 1993). As however, has revealed that improvement assess. I propose that occupational con-

Baum and Law (1997) noted, clients in performance components does not cerns become the primary consideration

need to understand the purpose of occu- automatically translate into improved guiding the selection of assessments, and

pational therapy and its potential out- occupational performance (Fisher, 1992b; I outline three broad strategies to evalu-

comes as much as therapists need to Mathiowetz & Haugen, 1995; Schmidt, ate the use of available assessments with-

understand clients’ occupational perfor- 1988; Trombly, 1995, 1999). Thus, an in occupation-based evaluations. These

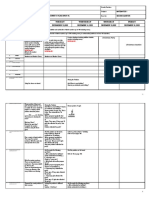

mance problems. Failure to communi- increase in concentration span, for exam- strategies are presented in Figure 1. An

cate the purpose or anticipated outcomes ple, may not carry over into improved assumption underlying the discussion is

of intervention would, in effect, com- performance of work tasks. that occupational therapy evaluations

promise the principles of client-centered A third concern is that occupational and interventions are guided by theory.

occupational therapy because clients can- therapists who focus their evaluations Examples of the influence of theoretical

not fully engage in processes they do not solely on performance components risk frameworks on clinical reasoning are

understand (Pollock & McColl, 1998). focusing treatment around those compo- incorporated throughout the discussion.

In addition, failing to communicate the nents, thus failing to address critical

purpose of intervention is contrary to occupational issues. These issues might What To Assess

the increasing consumer demand that include, for example, volitional aspects Trombly (1995) advised occupational

any evaluation of function is both rele- of performance (Fisher, 1992b) or attitu- therapists to enact “top–down” evalua-

vant and useful to the person being dinal, organizational, or physical envi- tions, that is, to first focus on clients’

assessed (Batavia, 1992). ronmental barriers to occupation occupational performance issues rather

A second area of concern is which (Roulstone, 1998). As Kielhofner (1993) than the underlying occupational perfor-

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 463

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 06/22/2017 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

to assess and in what sequence. From this the core themes of their lives and the

perspective, and working top–down, meanings they experience and express

occupational therapists’ first imperative is through occupation (i.e., why people do

to understand clients as occupational something, what they might do in the

beings who create meaning in their lives future, who they perceive they are

through the occupations in which they becoming).

engage. Framed by this understanding, To understand clients as occupation-

the function or purpose of the occupa- al beings, the first focus of occupation-

tions that are problematic, the form those based assessment, therapists are guided

occupations take, whether the cause of by the following questions:

the problem is clear, and the performance

components or environmental conditions • How does this person describe him-

that may be impeding performance can self or herself? What kind of person

be addressed. Each dimension of the is he or she?

occupationally based evaluation is dis- • How does this person’s occupation

cussed in sequence as follows. contribute to constructing or main-

taining identity, to expressing and

Understanding People as experiencing meaning, or to achiev-

Occupational Beings ing his or her life purpose?

The occupational therapy literature offers • What are this person’s occupational

various perspectives on people as occupa- goals? That is, what identity or

tional beings as well as the meanings that meanings does the person wish to

people experience and express through achieve?

daily occupation that center on the • In what ways do the occupations

notion of identity. For example, Kielhofner, this person finds problematic affect

Borell, Burke, Helfrich, and Nygard his or her identity or expression or

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for (1995) proposed in the Model of Human experience of meaning?

occupation-based assessment. Occupation that people have a “com-

monsense” understanding of who they Examples of assessments that address

mance limitations. In this way, she are, what they might do, the contexts in occupational identity are the OPHI-II

argued, clients would more easily under- which they might act, and who they and the Occupational Case Analysis

stand the unique concerns of occupation- might become. People’s understandings Interview and Rating Scale (Kaplan &

al therapy and more readily make sense of themselves are constructed and Kielhofner, 1989). Both assessments gen-

of occupational therapy intervention. revealed in their volitional narratives erate data about people’s occupational

Further, Trombly argued that therapists (Helfrich, Kielhofner, & Mattingly, histories. The Volitional Questionnaire

need to evaluate performance compo- 1994). (de las Heras, 1993) is an example of an

nents only when the cause of the prob- A related concept—occupational assessment that helps therapists to under-

lem is not already apparent in order to identity—emerged from research into the stand the meaning or volitional aspects of

determine how to intervene. Accepting psychometric properties of second ver- occupational performance from the per-

Trombly and others’ rationale, however, sion of the Occupational Performance former’s perspective.

does not necessarily assist therapists History Interview (OPHI-II; Kielhofner In addition to understanding the

trained and skilled in “bottom–up” eval- et al., 1998). The developers defined meanings clients experience and express

uation to determine how to proceed. occupational identity as the extent to through occupation, occupational thera-

This section outlines a top–down evalua- which the person has integrated and feels pists are concerned with whether those

tion strategy. confident about his or her values, inter- meanings are acceptable to others.

According to Clark et al. (1991), ests, and occupational roles. Christiansen Kielhofner (1995), among others, has

people are occupational beings. Occupa- (1999) and Crabtree (1998) each con- reminded us that the persons in our

tion can be conceptualized in terms of its cluded that identity is developed and clients’ social environments both create

performance components (or substrates expressed through occupation and that the social contexts within which they act

[Clark et al., 1991]), form, function, and occupation is the vehicle for experiencing and provide opportunities to enter occu-

meaning, where the form of an occupa- life meaning. Similar ideas are incorpo- pational roles. For example, a child who

tion refers to its observable features rated within the Canadian Model of takes his wheelchair to the beach, thus

(Clark, Wood, & Larson, 1998) rather Occupational Performance (Canadian exposing it to sand and salt water, may

than the broader definition proposed by Association of Occupational Therapists, challenge his parents’ value of looking

Nelson (1988). Proposed here is that 1997), where people’s occupations are after such expensive equipment better.

thinking about occupational performance centered on their spirituality, their inner Alternatively, parents may encourage

in terms of its meaning, function, form, core or essence. Taken together, these their child to venture onto the beach,

and performance components may guide ideas suggest that understanding people believing the child has a right to this

therapists’ clinical reasoning about what as occupational beings is to understand experience. Therapists need to under-

464 July/August 2001, Volume 55, Number 4

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 06/22/2017 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

stand whether a client’s occupations fit fer from that of the recipient is impor- The first questions, therefore, are as fol-

with the occupational roles and expecta- tant. The essential questions for under- lows:

tions of the client’s social environment standing the function of occupations are

and to ensure that the occupations they as follows: • What actions are required to com-

propose or endorse are acceptable to and plete the occupation successfully?

valued by the client. Generally, this infor- • What functions are disrupted by the That is, what will be observed to

mation is sought through interviewing all occupational challenges this person happen?

persons concerned. experiences, and who is affected? For • Where, when, and how often can

example, is the disruption an issue the occupation be observed?

Understanding the Function of health, happiness, generating an • What performance standards will

of Occupations income, parenting one’s children, apply? That is, what quality of per-

Understanding the function of occupa- getting along with others, or main- formance will be observed?

tions that are affected by disability, envi- taining a clean and comfortable • What will happen as a result of per-

ronmental disruption, or occupational home environment? forming the occupation? What, if

role transitions, such as retirement, is a • In what ways does the physical envi- any, outcomes might be observed?

second focus for data gathering. People ronment support or impede the per- • Does the environment in which the

engage in occupation for a wide variety son from achieving the intended occupation is performed provide the

of reasons, which Wilcock (1993) sum- purpose of his or her occupation? necessary resources?

marized as meeting “immediate bodily • In what ways do others’ occupations • In what ways does the environment

needs of sustenance, self care and shel- support or hinder the person, and support or hinder performance?

ter”; developing “skills, social structures how might they better provide sup-

and technology aimed at safety and supe- port? Having understood the requirements

riority over predators and the environ- and context of performance, therapists

ment”; and exercising personal capacities An example of an assessment that need to establish the nature and extent of

(p. 20). Research that has explored peo- captures information about the function the disruption to performance. In this

ple’s engagement in particular occupa- of occupation in people’s lives is the regard, acknowledging disruptions

tions has revealed other, more specific Canadian Occupational Performance observable to the performer as well as to

functions or purposes. For example, Segal Measure (COPM; Law et al., 1994) in an outside observer is important. The

(1999) found that parents select and con- which clients identify occupations as part broad questions, therefore, are as follows:

struct occupations for their children in of their productivity, leisure, or self-care

order to bring family members together; and prioritize them in order of impor- • What is the quality of the person’s

share their experiences; and provide tance and personal satisfaction with per- current occupational performance,

opportunities for the children to learn formance. including its strengths and weak-

something of their religious, ethnic, and nesses?

family background and of their parents’ Understanding the Form • How does the existing form of the

interests. Similarly, women demonstrate of Occupations occupation compare to the quality

real caring for their partners and children The form of an occupation, as defined by of performance he or she is striving

by acknowledging their individual prefer- Clark et al. (1998), refers to its observ- for or required to achieve?

ences as they shop for groceries and plan able features. In a top–down, occupation- • How has the person adapted to or

and prepare meals. For these women, based assessment, establishing the quality accommodated his or her occupa-

these occupations also function as an of the occupational performance, its tional performance challenges?

expression of individual skill, pride, and observable features, within the environ-

responsibility (De Vault, 1991; Miller, ment in which it is performed is the next Finally, therapists will be concerned

1998). focus. This process includes both deter- about potential for change in perfor-

Thus, the function of an occupation mining the nature and extent of any mance. Relevant questions are the follow-

refers to its purpose or importance within observable disruption to performance ing:

the person’s daily realm of occupations and identifying occupational perfor-

and the contribution it makes to his or mance skills and environmental opportu- • Does the person have the capacity to

her own and others’ lifestyles. In that nities that support performance. improve the quality of his or her

people generally interdepend on others Understanding the ways in which performance?

for their survival and success, an individ- occupational performance is disrupted • In what ways might the occupation

ual’s occupations may range from provid- and the extent of that disruption requires or the occupational context be mod-

ing support for others to creating unneces- an understanding of the occupation in ified to better support performance?

sary and excessive work. Between these terms of the capacities required to carry it

extremes, occupations may be experi- out successfully. Occupational perfor- Exactly how these questions are

enced as mutually enjoyed or beneficial mance is the product of the person, the framed will depend on and vary with the

or as providing a focus for other’s actions occupation, and the environment models informing therapists’ clinical rea-

and care. In this regard, acknowledging (Kielhofner, 1995) and is best under- soning. For example, the Model of

that the performer’s perspective may dif- stood in the context of its performance. Human Occupation would frame these

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 465

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 06/22/2017 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

questions in terms of the setting in which to the client and the therapist is the pri- the core construct is skillful performance

the occupational behavior occurs, the mary professional issue in relation to in both motor and process domains.

person’s occupational roles, motor and evaluation (Batavia, 1992). In the context Another example is the Volitional

process skills, and so on. Relevant assess- of occupational therapy in which occupa- Questionnaire, which involves observing

ments would include the Assessment of tion is both a goal and a means of thera- a nonverbal client’s behavior while

Motor and Process Skills (AMPS; Fisher, peutic intervention (Moyers, 1999), engaged in an occupation to understand

1994b), the Assessment of Communi- ensuring that assessments are relevant what motivates him or her. The core con-

cation and Interaction Skills (Salamy, and useful means identifying and using struct in this assessment is volition for

Simon, & Kielhofner, 1993), and the ones that have an occupational basis. occupation. Examples of assessments in

Functional Independence Measure Three broad strategies to analyze the which occupation performance is the

(Keith, Granger, Hamilton, & Sherwin, occupational basis of assessments are (a) core construct are the COPM and the

1987). All of these assessments gather determining whether the assessment Self Assessment of Occupational

information about the skillfulness or actually measures some aspect of occupa- Functioning (Baron & Curtin, 1990),

effectiveness of the person’s performance tion, (b) identifying what kind of occu- both of which ask clients to evaluate their

within the environment. pation(s) the assessment involves and satisfaction with their level of occupa-

how clients might experience those occu- tional performance as a basis for collabo-

Evaluating Performance Components pations, and (c) analyzing whether the rative treatment planning.

Finally, if the cause of the occupational occupations incorporated in the assess- The second component of analyzing

dysfunction a client experiences is not ment are real or simulated and familiar whether and how an assessment measures

already evident, evaluation of the nature or unfamiliar. These strategies are dis- occupation is determining whether the

and extent of deficits in the components cussed here, and questions to analyze “philosophy, rationale, and frame of ref-

of occupational performance may be nec- critically whether assessments are occupa- erence used in constructing the instru-

essary (Baum & Law, 1997; Mathiowetz, tion based are proposed. ment” (Opacich, 1991, p. 369) is occupa-

1993; Pollock & McColl, 1998). As tional or supports an understanding of

Coster (1998) noted, the therapist uses Does the Assessment Measure occupation. For assessments developed to

knowledge of the cause of observed dys- Occupation? operationalize specific theories of occupa-

function to select appropriate interven- As previously discussed, a top–down, tional performance, such as the Model of

tion strategies. For example, establishing occupation-based evaluation process Human Occupation or the Canadian

that a client has difficulty shampooing looks at the meaning of occupation; the Model of Occupational Performance, this

her hair because of limited range of function or purpose of occupation within process is straightforward. For other

movement at the shoulder points to bio- people’s lives; the form of their occupa- assessments, however, the underpinning

mechanical intervention, whereas diffi- tional performance; and, if necessary, the philosophy or theory is less evident either

culty with the same task because of performance components or environ- because the developers did not explicitly

cognitive dysfunction subsequent to a mental conditions that support or restrict identify the theory informing their think-

traumatic brain injury points to cognitive occupational performance. Two compo- ing or because the relationship of the

rehabilitation approaches. nents aid in judging whether a particular philosophy or rationale to occupational

Many occupational therapy assess- assessment is occupation based: deter- performance is less direct. For example,

ments generate data about the status of mining whether the assessment measures the Refined ADL Assessment Scale for

the components underlying effective per- some aspect of occupation, such as the Patients with Alzheimer’s and Related

formance. For example, the Bay Area meaning of occupation or the skillfulness Disorders (Tappen, 1994) does not

Functional Performance Evaluation of performance, and determining whether explicitly identify an underlying theory

(BaFPE; Bloomer & Williams, 1986) occupation is the core construct of the base. The author’s qualification as a regis-

assesses cognitive abilities, and the Jebsen assessment. tered nurse and the assessment’s concern

Hand Function Test (Jebsen, Taylor, Perhaps the most obvious indicator with need for nursing home admission

Trieschmann, Trotter, & Howard, 1969) that occupation is the core construct of and type and level of assistance required

measures dexterity in the context of sim- an assessment is that the assessment to complete activities of daily living tasks,

ulated tasks of daily living. Further, some involves people carrying out an occupa- however, reveal an underlying philosophy

assessments focus on the environmental tion; documenting their occupational of care delivery and minimizing care

context of performance. For example, the performance; or talking about the impor- requirements.

Ward Atmosphere Scale (Moos, 1989) tance or meaning of occupations, how In contrast, the Automatic Thoughts

assesses the perceived social expectations their occupations are organized, or their Questionnaire (Hollon & Kendall, 1980)

and rules of a rehabilitation setting and satisfaction with their occupational per- is clearly based on cognitive behavioral

the ways in which self-reliant occupation- formance. For example, the AMPS theory, which posits that changing the

al performance is supported or restricted. assesses performance of two or three way people think about themselves and

familiar domestic or self-care tasks of the things that happen to them can

Selecting Occupation-Based choice while an occupational therapist change their feelings and behaviors. To

Assessments observes the skillfulness of the client’s use data generated by the Automatic

Determining how the data generated by performance. This assessment specifically Thoughts Questionnaire to change a per-

an assessment will be relevant and useful evaluates motor and process skills, and son’s experience of particular occupations

466 July/August 2001, Volume 55, Number 4

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 06/22/2017 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

requires knowledge about both cognitive A further consideration in all aspects cult. In addition, clients with cognitive

behavioral theory and the role that cogni- of occupational therapy practice is the dysfunction are likely to be confused by

tion plays in occupation. For example, in importance of addressing cultural issues. assessment activities that are not substan-

the context of the Model of Human In relation to evaluation processes, this tially the same as the occupations they

Occupation, automatic thoughts might concern raises issues about whether the find problematic. To avoid these prob-

influence the processes of anticipating, occupation of being assessed is culturally lems, I suggest that therapists seeking to

choosing, experiencing, and interpreting safe (Hocking, 1998; Hocking & establish occupationally based practice

occupational behavior (Kielhofner et al., Whiteford, 1995). For an assessment to may be better served by assessments that

1995). In this case, occupational thera- be culturally safe, it should not incorpo- involve real rather than simulated occupa-

pists themselves must judge their ability rate concepts that are foreign or irrele- tion whenever possible.

to make the necessary links between the vant in the person’s cultural context, A related concern is whether the

theory base of the assessment and occu- practices that contravene codes of mod- assessment involves familiar or unfamiliar

pation. esty or privacy, or expectations that the occupations. Many assessments designed

Questions to guide therapists’ evalu- person will self-report or make decisions by psychologists expose clients to tasks

ations of the occupational basis of assess- in ways that are not culturally sanc- that they have not had the opportunity

ments are the following: tioned. Many assessments that occupa- to practice. Indeed, opportunities to

tional therapists use, for example, have practice assessment tasks render the

• Is occupation the core construct an underlying assumption that persons assessment useless in that the results can

measured by the assessment? Does are self-determining, autonomous agents. no longer be taken as representative of

the assessment evaluate the meaning, Within some cultures, however, making general skill levels. The BaFPE is an

function, form, or components of decisions without reference to the family occupational therapy assessment that is

occupational performance or the or wider social group would be consid- based on similar premises and composed

ways in which the environment sup- ered selfish and present a danger to group of a set of tasks intended to be unfamiliar

ports or impedes occupational per- cohesion. Relevant questions to evaluate to clients. In contrast, the AMPS stipu-

formance? how clients may experience the occupa- lates that the assessment tasks be familiar

• Does the assessment involve people tion of being evaluated are as follows: to the client and carried out in an envi-

in carrying out an occupation or ronment to which he or she has been ori-

documenting or talking about their • In what ways does the assessment ented. The difference lies in the intent of

occupational performance? protocol constrain how the therapist the AMPS to evaluate skill in monitoring

• Are the philosophy, rationale, and may interact with the client? How one’s own actions in the midst of an

frame of reference of the assessment may any constraints to interaction unfolding occupation rather than assess-

occupational? affect the development or mainte- ing underlying performance capabilities.

nance of a therapeutic relationship? Therapists need to determine whether

What Kind of Occupation • Is the assessment culturally safe? observing clients performing familiar or

is the Assessment? unfamiliar tasks will best reveal the

As well as considering whether occupa- Are the Occupations Real or nature and extent of the occupational

tion is the core concept of an assessment, Simulated, Familiar or Unfamiliar? performance deficits their clients experi-

evaluating the occupational basis of an Also important when analyzing the occu- ence. Similarly, whether the environment

assessment involves considering the pational basis of assessments is whether in which the assessment is completed is

assessment itself an occupation. Thus, they involve carrying out real or simulat- familiar or unfamiliar may have motiva-

therapists are concerned with what kind ed occupations. For example, the Struc- tional implications or change the quality

of occupation it will be for the client to tured Observational Test of Function of the performance (Park, Fisher, &

“be assessed.” For occupational therapists (Laver & Powell, 1995) involves carrying Velozo, 1994).

who strive to achieve client-centered out basic self-care tasks to judge the A final consideration is the kind of

practice, an important consideration is impact of perceptual and cognitive data the assessment will generate. For

the potential impact of formal evaluation deficits on task performance. In contrast, example, will the final score be a measure

processes on the developing therapeutic the tasks involved in perceptual tests, such of the person’s performance skills or satis-

relationship. Managh and Cook (1993), as the Visual Cancellation Test (Abreu, faction with their occupational perfor-

for example, found that many of the 1992), or in assessments like the Purdue mance, or will it be a measurement of

Canadian occupational therapists they Pegboard (Tiffen, 1968) require clients to their performance capacity (e.g., degrees

studied modified the administration pro- perform simulated activities that are not of movement at a joint)? Although either

tocol of the BaFPE. What these thera- part of everyday life. In occupational sci- or both may be useful, if the intent of

pists reported was that the assessment ence terminology, such simulations are occupational therapy intervention is to

protocol constrained how they interacted not occupations in that they are not change occupational performance, it is

with clients. They perceived administer- “named in the lexicon of the culture” more clearly demonstrated by assess-

ing the assessment as a coldly formal (Clark et al., 1991, p. 301) and may not ments that directly measure and describe

occupation that did not allow them to be elicit the same motivation to perform or that performance.

encouraging of their clients’ efforts or similar motor patterns as the real-life Questions that summarize the key

supportive of their failures. occupation the client experiences as diffi- points made here are the following:

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 467

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 06/22/2017 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

• Does the assessment involve real or Second Asia-Pacific Occupational Therapy right test, minimizing the limitations.

simulated occupations? What moti- Congress in Taipei, Taiwan, September American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 46,

11–14, 1999. 278–281.

vational or performance implications

Fisher, A. (1994a). Functional assess-

may the use of simulated occupa-

References ment and occupation: Critical issues for occu-

tions have? pational therapy. New Zealand Journal of

Abreu, B. C. (1992). The quadraphonic

• Does the assessment involve familiar Occupational Therapy, 45, 13–19.

approach: Management of cognitive-percep-

or unfamiliar occupations carried tual and postural control dysfunction. Fisher, A. (1994b). The Assessment of

out in familiar or unfamiliar envi- Occupational Therapy Practice, 3(4), 12–29. Motor and Process Skills (Version 8.0).

ronments? What are the implica- Baron, K. B., & Curtin, C. (1990). A Unpublished test manual, Colorado State

University, Fort Collins.

tions for the usefulness of the data manual for use with the Self Assessment of

Occupational Functioning. Chicago: Fisher, A. G., & Short-DeGraff, M.

to be generated?

Department of Occupational Therapy, (1993). Nationally Speaking—Improving

• Does the data generated by the functional assessment in occupational thera-

University of Illinois at Chicago.

assessment summarize occupational py: Recommendations and philosophy for

Batavia, A. I. (1992). Assessing the func-

performance or the status of perfor- tion of functional assessment: A consumer change. American Journal of Occupational

mance components? perspective. Disability and Rehabilitation, Therapy, 47, 199–201.

14(3), 156–160. Gillette, N. P. (1991). The Issue Is—

Conclusion Baum, C. M., & Law, M. (1997). Research directions for occupational therapy.

Occupational therapy practice: Focusing on American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45,

Evaluation is the basis from which occu- 563–565.

occupational performance. American Journal

pational therapists define the nature of Helfrich, C., Kielhofner, G., &

of Occupational Therapy, 51, 277–288.

their clients’ occupational performance Mattingly, C. (1994). Volition as narrative:

Bloomer, J., & Williams, S. (1986). Bay

challenges, determine clients’ priorities, Area Functional Performance Evaluation Understanding motivation in chronic illness.

and negotiate the goals of interventions. (BaFPE): Task oriented assessment and social American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 48,

311–317.

In addition, it is through this process that interaction scale. San Francisco: USCF.

Hocking, C. (1998, May). Partnership

clients come to understand the nature and Canadian Association of Occupational

Therapists. (1997). Enabling occupation: An and participation: The bicultural New

outcomes of occupational therapy and the Zealand context. World Federation of

occupational therapy perspective. Ottawa, ON:

ways in which the occupational therapist Occupational Therapists Bulletin, 37, 51–55.

CAOT Publications ACE.

will engage them in the process of achiev- Hocking, C., & Whiteford, G. (1995).

Christiansen, C. H. (1999). Defining

ing valued occupational performance out- lives: Occupation as identity: An essay on Viewpoint: Multiculturalism in occupational

comes. In this article, I have extended competence, coherence, and the creation of therapy: A time for reflection on core values.

Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 42,

Trombly’s (1995) notion of top–down meaning, 1999 Eleanor Clarke Slagle lecture.

American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 53, 172–175.

evaluation processes and interpreted what

547–558. Hollon, S. D., & Kendall, P. C. (1980).

such a process might mean in occupation- Cognitive self statements in depression:

Clark, F. A., Parham, D., Carlson, M.

al terms. I have proposed applying a Development of an automatic thoughts ques-

E., Frank, G., Jackson, J., Pierce, D., Wolfe,

framework of conceptualizing occupation R. J., & Zemke, R. (1991). Occupational sci- tionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 4,

as a hierarchy consisting of performance ence: Academic innovation in the service of 383–395.

components (at the bottom), occupational occupational therapy’s future. American Jebsen, R. H., Taylor, N., Trieschmann,

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 45, 300–310. R., Trotter, M., & Howard, L. (1969). An

form, the function of the occupation in a objective and standardized test of hand func-

person’s life, and the meaning of occupa- Clark, F., Wood, W., & Larson, E. A.

(1998). Occupational science: Occupational tion. Archives of Physical Medicine and

tion and its contribution to creating or therapy’s legacy for the 21st century. In M. E. Rehabilitation, 50, 311–319.

maintaining an identity (at the top). Neistadt & E. B. Crepeau (Eds.), Willard and Kaplan, K., & Kielhofner, G. (1989).

Therapists are urged to analyze Spackman’s occupational therapy (9th ed., pp. Occupational Case Analysis Interview and

assessments to determine whether they in 13–21). Philadelphia: Lippincott. Rating Scale. Thorofare, NJ: Slack.

fact collect data about occupation and Coster, W. (1998). Occupation-centered Keith, R. A., Granger, C. V., Hamilton,

assessment of children. American Journal of B. B., & Sherwin, F. S. (1987). The Functional

how well their underlying theoretical Independence Measure: A new tool for rehabil-

framework relates to occupational perfor- Occupational Therapy, 52, 337–344.

itation. In M. G. Eisenberg & R. C. Grzesiak

mance. Also important is the considera- Crabtree, J. L. (1998). The end of occu- (Eds.), Advances in clinical rehabilitation (Vol.

pational therapy. American Journal of 1, pp. 6–18). New York: Springer-Verlag.

tion of the occupation of being assessed Occupational Therapy, 52, 205–214.

in terms of its impact on the therapeutic Kielhofner, G. (1993). The Issue Is—

de las Heras, C. G. (1993). A user’s guide Functional assessment: Toward a dialectical

relationship and its cultural meanings. A to the Volitional Questionnaire (2nd ed.). view of person–environment relations.

final consideration is whether the activi- Chicago: University of Illinois at Chicago. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 47,

ties within the assessment are real or sim- De Vault, M. L. (1991). Feeding the fam- 248–251.

ulated, familiar or unfamiliar occupations. ily. The social organization of caring as gendered Kielhofner, G. (Ed.). (1995). A model of

In this way, it is argued, therapists will be work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. human occupation: Theory and application

enabled to implement assessments that Fisher, A. (1992a). The Foundation— (2nd ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Functional measures, part 1: What is func- Kielhofner, G., Borell, L., Burke, J.,

provide an occupationally based, client-

tion, what should we measure, and how Helfrich, C., & Nygard, L. (1995). Volition

centered foundation for practice. ▲ should we measure it? American Journal of subsystem. In G. Kielhofner (Ed.), A model of

Occupational Therapy, 46, 183–185. human occupation: Theory and application

Acknowledgment Fisher, A. (1992b). The Foundation— (2nd ed., pp. 39–62). Baltimore: Williams &

This article is based on a presentation to the Functional measures, part 2: Selecting the Wilkins.

468 July/August 2001, Volume 55, Number 4

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 06/22/2017 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

Kielhofner, G., Mallinson, T., Crawford, Scale manual (2nd ed.). Palo Alto, CA: Schmidt. R. A. (1988). Motor control

C., Nowak, M., Rigby, M., Henry, A., & Consulting Psychologists Press. and learning: A behavioral emphasis (2nd ed.).

Walens, D. (1998). A user’s manual for the Moyers, P. A. (1999). The guide to Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Occupational Performance History Interview occupational therapy practice. American Segal, R. (1999). Doing for others:

(Version 2.0, OPHI-II). Chicago: University Journal of Occupational Therapy, 53, 247–322. Occupations within families with children

of Illinois at Chicago. Nelson, D. L. (1988). Occupation: who have special needs. Journal of

Laver, A. J., & Powell, G. E. (1995). Form and performance. American Journal of Occupational Science, 6(2), 53–60.

The Structured Observational Test of Function Occupational Therapy, 42, 633–641. Tappen, R. M. (1994, June). Develop-

(SOTOF). Windsor, UK: NFER Nelson. Opacich, K. J. (1991). Assessment and ment of the Refined ADL Assessment Scale

Law, M., Baptiste, S., Carswell, A., informed decision-making. In C. Christiansen for patients with Alzheimer’s and related dis-

McColl, M. A., Polatajko, H., & Pollock, N. & C. Baum (Eds.), Occupational therapy: orders. Journal of Gerontological Nursing,

(1994). The Canadian Occupational Overcoming occupational performance deficits 36–42.

Performance Measure (2nd ed.). Ottawa, ON: (pp. 354–372). Thorofare, NJ: Slack.

CAOT Publications. Tiffen, J. (1968). Purdue Pegboard:

Park, S., Fisher, A. G., & Velozo, C. A. Examiner manual. Chicago: Science Research

Managh, M. F., & Cook, J. V. (1993). (1994). Using the Assessment of Motor and Associates.

The use of standardized assessment in occupa- Process Skills to compare occupational perfor-

tional therapy: The BaFPE-R. American mance between clinic and home settings. Trombly, C. (1993). The Issue Is—

Journal of Occupational Therapy, 47, 877–884. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 48, Anticipating the future: Assessment of occu-

Mathiowetz, V. (1993). Role of physical 679–709. pational function. American Journal of

performance component evaluations in occu- Occupational Therapy, 47, 253–257.

Pollock, N., & McColl, M. A. (1998).

pational therapy functional assessment. Assessment in client-centred occupational Trombly, C. (Ed.). (1995). Occupational

American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 47, therapy. In M. Law (Ed.), Client-centred occu- therapy for physical dysfunction (4th ed.).

225–230. pational therapy (pp. 89–105). Thorofare, NJ: Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins.

Mathiowetz, V., & Haugen, J. B. Slack. Trombly, C. (1999, September).

(1995). Evaluation of motor behavior: Roulstone, A. (1998). Enabling technolo- Occupation-as-means and occupation-as-end:

Traditional and contemporary views. In C. A. gy: Disabled people, work and new technology. Remediation and restoration of occupational

Trombly (Ed.), Occupational therapy for physi- Buckingham, UK: Open University Press. performance. Paper presented at the Second

cal dysfunction (4th ed., pp. 157–186). Salamy, M., Simon, S., & Kielhofner, G. Asia-Pacific Occupational Therapy Congress,

Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. (1993). The Assessment of Communication and Taipei, Taiwan.

Miller, D. (1998). A theory of shopping. Interaction Skills (Research Version). Chicago: Wilcock, A. (1993). A theory of the

Cambridge, MA: Polity. Department of Occupational Therapy, human need for occupation. Journal of

Moos, R. H. (1989). Ward Atmosphere University of Illinois at Chicago. Occupational Science: Australia, 1(1), 17–24.

The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 469

Downloaded From: http://ajot.aota.org/ on 06/22/2017 Terms of Use: http://AOTA.org/terms

You might also like

- Occupation Based AssessmentDocument7 pagesOccupation Based Assessmentapi-242989812No ratings yet

- Accelerating Complex Problem-Solving Skills: Problem-Centered Training Design MethodsFrom EverandAccelerating Complex Problem-Solving Skills: Problem-Centered Training Design MethodsNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Evaluation and InterviewingDocument19 pagesIntroduction To Evaluation and InterviewingMaria AiramNo ratings yet

- Occupation-Centered Assessment of Children: Wendy CosterDocument8 pagesOccupation-Centered Assessment of Children: Wendy CosterAna Claudia GomesNo ratings yet

- Handbook for Strategic HR - Section 3: Use of Self as an Instrument of ChangeFrom EverandHandbook for Strategic HR - Section 3: Use of Self as an Instrument of ChangeNo ratings yet

- What Is Professionalism in Occupational Therapy? A Concept AnalysisDocument14 pagesWhat Is Professionalism in Occupational Therapy? A Concept AnalysisNataliaNo ratings yet

- Bottom-Up or Top-Down Evaluation: Is One Better Than The Other?Document6 pagesBottom-Up or Top-Down Evaluation: Is One Better Than The Other?Fernanda Pinto BastoNo ratings yet

- Areer Ounseling: Ennifer IDDDocument17 pagesAreer Ounseling: Ennifer IDDsherla TorioNo ratings yet

- Perspectives On Models of Job PerformancDocument12 pagesPerspectives On Models of Job PerformancGri PrusNo ratings yet

- Workplace CounsellingDocument5 pagesWorkplace CounsellingUmi AfidaNo ratings yet

- 1.professional ReasoningDocument23 pages1.professional ReasoningAswathiNo ratings yet

- Capitol Campbell - Diferente Individuale Relevante Pentru PerformantaDocument43 pagesCapitol Campbell - Diferente Individuale Relevante Pentru PerformantaMonica MuresanNo ratings yet

- Paradigm Critique PaperDocument15 pagesParadigm Critique Papergkempf10No ratings yet

- 20240419T125234 Oct3104 Evaluation and AssessmentDocument16 pages20240419T125234 Oct3104 Evaluation and Assessmentanjasnellenburg5No ratings yet

- Lait StressWorkStudy 2002Document21 pagesLait StressWorkStudy 2002Ochko BodigNo ratings yet

- 569 PDFDocument7 pages569 PDFferas ahmedNo ratings yet

- Feedback Quality and Performance in Organisatio - 2021 - The Leadership QuarterlDocument12 pagesFeedback Quality and Performance in Organisatio - 2021 - The Leadership Quarterljoe joeNo ratings yet

- Work Motivation: Theory and PracticeDocument10 pagesWork Motivation: Theory and PracticeZach YolkNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment Research MethodsDocument8 pagesFinal Assignment Research MethodsBorsha Rima100% (2)

- Essay - Final VersionDocument10 pagesEssay - Final VersionTrương Hoài NamNo ratings yet

- Psy160 - I - o PsychologyDocument3 pagesPsy160 - I - o PsychologyDiane SauraneNo ratings yet

- Individual Assignment 2: Article Review (Models of Workplace Counselling)Document8 pagesIndividual Assignment 2: Article Review (Models of Workplace Counselling)Umi AfidaNo ratings yet

- Competence and CompetencyDocument9 pagesCompetence and Competencytomor2No ratings yet

- Performance Appraisal Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesPerformance Appraisal Literature ReviewVinoth Kumar67% (9)

- Impact of Employee Empowerment On Employee's Performance in The Context of Banking Sector of PakistanDocument8 pagesImpact of Employee Empowerment On Employee's Performance in The Context of Banking Sector of PakistanAsia ayazNo ratings yet

- Work As A Calling: Theoretical ModelDocument17 pagesWork As A Calling: Theoretical ModelIsabel DuarteNo ratings yet

- Human Resource Management - 2004 - Saari - Employee Attitudes and Job SatisfactionDocument13 pagesHuman Resource Management - 2004 - Saari - Employee Attitudes and Job SatisfactionAmrithaNo ratings yet

- S R P F R R A S P: Ubject: EseacrhDocument78 pagesS R P F R R A S P: Ubject: EseacrhWaqas QurashiNo ratings yet

- WEIMSDocument16 pagesWEIMSJeeta Sarkar100% (1)

- Industrial-Organizational Psych Reviewer PDFDocument8 pagesIndustrial-Organizational Psych Reviewer PDFRagdoll Sparrow100% (3)

- Reviewer IO PsychologyDocument9 pagesReviewer IO Psychologymariya diariesNo ratings yet

- Assessing The PDFDocument18 pagesAssessing The PDFSahar Hayat AwanNo ratings yet

- Ahearne, Mathieu, & Rapp (2005)Document11 pagesAhearne, Mathieu, & Rapp (2005)Ria Anggraeni100% (1)

- An Examination of Dimensions of Psychological Empowerment Scale For Service EmployeesDocument7 pagesAn Examination of Dimensions of Psychological Empowerment Scale For Service Employeesadesgy tiaraNo ratings yet

- Employee Attitudes and Job SatisfactionDocument14 pagesEmployee Attitudes and Job SatisfactionBobby DNo ratings yet

- Chaps 1-5 TemplateDocument30 pagesChaps 1-5 TemplateJanssen FajardoNo ratings yet

- Leadership As2 Mutasem Amro - 16402752Document18 pagesLeadership As2 Mutasem Amro - 16402752Mutasem AmrNo ratings yet

- Competence and CompetencyDocument6 pagesCompetence and CompetencyJohn Kenworthy100% (5)

- Assessment in The Workplace A Competency-Based AppDocument7 pagesAssessment in The Workplace A Competency-Based AppMohamed IfanNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Improving Performance Using 1Document10 pagesRunning Head: Improving Performance Using 1Sean LoranNo ratings yet

- Quality of Work at LifeDocument34 pagesQuality of Work at LifeAmit PasiNo ratings yet

- Articles Arnold Bakker 245 PDFDocument9 pagesArticles Arnold Bakker 245 PDFFranzNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document3 pagesPresentation 1ridzuan.mdnoorNo ratings yet

- Employee Empowerment1Document14 pagesEmployee Empowerment1Farhat Binte HasanNo ratings yet

- Occupational Therapy Professional DeveloDocument12 pagesOccupational Therapy Professional DeveloDaniel LaraNo ratings yet

- Establishing Priorities in The Supervision HourDocument7 pagesEstablishing Priorities in The Supervision HourDianaSantiagoNo ratings yet

- Occupational Stress: Reflections On Theory and PracticeDocument16 pagesOccupational Stress: Reflections On Theory and PracticeAnonymous N9bM1y6HhjNo ratings yet

- CmopeDocument3 pagesCmopeEdu EduNo ratings yet

- Fisher (2013) Occupation-Centred Occupation-Based Occupation-FocusedDocument12 pagesFisher (2013) Occupation-Centred Occupation-Based Occupation-FocusedElianaMicaela100% (1)

- Human Resource Management Ethics and Professionals' Dilemmas: A Review and Research AgendaDocument11 pagesHuman Resource Management Ethics and Professionals' Dilemmas: A Review and Research AgendaLarisaNo ratings yet

- Blau 1999 AMJ ProfComitMTs PDFDocument10 pagesBlau 1999 AMJ ProfComitMTs PDFMarinelle TumanguilNo ratings yet

- OT Theories (In A Nutshell)Document8 pagesOT Theories (In A Nutshell)TaraJane House100% (1)

- Extract - Lishman - Chapter 26Document15 pagesExtract - Lishman - Chapter 26Roshni Patel ✫No ratings yet

- Paper - The Use of Psychometric Tests On Real Life SettingDocument8 pagesPaper - The Use of Psychometric Tests On Real Life SettingMaryam QonitaNo ratings yet

- Lavigne Forest Fernet Crevier-Braud 2014 Passion at Work and Workers Evaluation of Job Demands and Resources A Longitudinal StudyDocument12 pagesLavigne Forest Fernet Crevier-Braud 2014 Passion at Work and Workers Evaluation of Job Demands and Resources A Longitudinal StudyjenalonNo ratings yet

- What Motivates Employees According To Over 40 Years of Motivation SurveysDocument18 pagesWhat Motivates Employees According To Over 40 Years of Motivation SurveysAhmed BilalNo ratings yet

- A Qualitative Exploration of Employees' Views On Organisational CommitmentDocument10 pagesA Qualitative Exploration of Employees' Views On Organisational CommitmentMaverick CardsNo ratings yet

- Brachial Plexus Outcome Measure (BPOM)Document1 pageBrachial Plexus Outcome Measure (BPOM)jesscavalcanteNo ratings yet

- 04 SAISI Integration For Infants and Toddlers - Article - C WEBDocument14 pages04 SAISI Integration For Infants and Toddlers - Article - C WEBjesscavalcanteNo ratings yet

- The Ordering of Milestones in Language Development For Children From 1 To 6 Years of AgeDocument19 pagesThe Ordering of Milestones in Language Development For Children From 1 To 6 Years of AgejesscavalcanteNo ratings yet

- Jamapediatrics Morgan 2021 RV 210001 1620661880.02501-2Document14 pagesJamapediatrics Morgan 2021 RV 210001 1620661880.02501-2AnaCarinaPereiraNo ratings yet

- StrobeDocument3 pagesStrobejesscavalcanteNo ratings yet

- Milestone MomentsDocument60 pagesMilestone MomentsFiorellaBeatrizNo ratings yet

- Impact of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Early Child Cognitive Development: Initial Findings in A Longitudinal Observational Study of Child HealthDocument37 pagesImpact of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Early Child Cognitive Development: Initial Findings in A Longitudinal Observational Study of Child HealthDjNo ratings yet

- Potential Impact of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Communication and Language Skills in ChildrenDocument2 pagesPotential Impact of The COVID-19 Pandemic On Communication and Language Skills in ChildrenCristian Ferney PalechorNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Physical EducationDocument18 pagesLesson 1 Physical EducationJohnne Erika LarosaNo ratings yet

- Community Nursing Skill and CompetenceDocument54 pagesCommunity Nursing Skill and CompetenceHeri Zalmes Dodge TomahawkNo ratings yet

- Strategy ImplementationDocument14 pagesStrategy ImplementationAni SinghNo ratings yet

- G. V. Chulanova: Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State UniversityDocument75 pagesG. V. Chulanova: Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine Sumy State UniversityNastiaNo ratings yet

- Stanovich NotesDocument16 pagesStanovich NotesRana EwaisNo ratings yet

- Week 16 QTR 2 Math 1Document7 pagesWeek 16 QTR 2 Math 1Cjezpacia VictorinoNo ratings yet

- Metaphysics Ontology PDFDocument19 pagesMetaphysics Ontology PDFPedaka LaxmanaNo ratings yet

- TNCT Q2 Module6Document13 pagesTNCT Q2 Module6Leary John TambagahanNo ratings yet

- City and GuildsDocument9 pagesCity and GuildsIrfan AshrafNo ratings yet

- Graphomotor Activities.20140727.120415Document1 pageGraphomotor Activities.20140727.120415point3hookNo ratings yet

- I. Objectives: Mabini CollegesDocument3 pagesI. Objectives: Mabini CollegesMyla RicamaraNo ratings yet

- Coaching Conversations Using Socratic MethodDocument2 pagesCoaching Conversations Using Socratic MethodAditya Anand100% (1)

- Questioning Techniques - Communication Skills FromDocument6 pagesQuestioning Techniques - Communication Skills FromOye AjNo ratings yet

- InterviewDocument18 pagesInterviewHaritha DevinaniNo ratings yet

- Resume FactsheetDocument2 pagesResume FactsheetMajed BirdNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning On Students' Problem Solving Ability in Vector Analysis CourseDocument7 pagesThe Effectiveness of Problem-Based Learning On Students' Problem Solving Ability in Vector Analysis CourseVIRA ZANUBA KHOFSYAH Tarbiyah dan KeguruanNo ratings yet

- Pune Introduction To CommunicationresearchDocument25 pagesPune Introduction To CommunicationresearchTrending MakNo ratings yet

- Ethics of A Public Speaking: Our Lady of Ransom Catholic SchoolDocument9 pagesEthics of A Public Speaking: Our Lady of Ransom Catholic SchoolJeff NunagNo ratings yet

- SPACE CAT Intro NotesDocument25 pagesSPACE CAT Intro NotesWyatt CarteauxNo ratings yet

- SYNTAX ReviewerDocument13 pagesSYNTAX ReviewerMaxpein AbiNo ratings yet

- Activity Proposal For EnrichmentDocument3 pagesActivity Proposal For EnrichmentJayson100% (4)

- EntrepreneurDocument19 pagesEntrepreneurKeziah CarandangNo ratings yet

- An Educational Development PlanDocument1 pageAn Educational Development Planapi-258653522No ratings yet

- 2 - y B.ed Under Cbcs Cagp 15-16Document119 pages2 - y B.ed Under Cbcs Cagp 15-16Harsha HarshuNo ratings yet

- E-Waste Chapter 3Document23 pagesE-Waste Chapter 3Privilege T MurambadoroNo ratings yet

- EC 481K Preliminary Analysis Spring 2023Document2 pagesEC 481K Preliminary Analysis Spring 2023Han ZhongNo ratings yet

- Santanelli - Hypnosis Notes First Part of BookDocument3 pagesSantanelli - Hypnosis Notes First Part of BookdeanNo ratings yet

- Unit 3Document2 pagesUnit 3Cymonit MawileNo ratings yet

- Module 1 - 1 OBE, MQF and MQA Overview The BIG PictureDocument93 pagesModule 1 - 1 OBE, MQF and MQA Overview The BIG PictureMahatma Murthi100% (1)

- Linguistics Course OutlineDocument6 pagesLinguistics Course OutlineRobert TsuiNo ratings yet

- Summary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedFrom EverandSummary: The Psychology of Money: Timeless Lessons on Wealth, Greed, and Happiness by Morgan Housel: Key Takeaways, Summary & Analysis IncludedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (80)

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- ADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDFrom EverandADHD is Awesome: A Guide to (Mostly) Thriving with ADHDRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Think This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeFrom EverandThink This, Not That: 12 Mindshifts to Breakthrough Limiting Beliefs and Become Who You Were Born to BeRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (24)

- LIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionFrom EverandLIT: Life Ignition Tools: Use Nature's Playbook to Energize Your Brain, Spark Ideas, and Ignite ActionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (404)

- Summary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia MD, With Bill Gifford: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (42)

- Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsFrom EverandRaising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young AdultsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaFrom EverandThe Body Keeps the Score by Bessel Van der Kolk, M.D. - Book Summary: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of TraumaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandOutlive: The Science and Art of Longevity by Peter Attia: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Gut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerFrom EverandGut: the new and revised Sunday Times bestsellerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (392)

- When the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandWhen the Body Says No by Gabor Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- The Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsFrom EverandThe Ritual Effect: From Habit to Ritual, Harness the Surprising Power of Everyday ActionsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlFrom EverandThe Marshmallow Test: Mastering Self-ControlRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (58)

- Dark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingFrom EverandDark Psychology: Learn To Influence Anyone Using Mind Control, Manipulation And Deception With Secret Techniques Of Dark Persuasion, Undetected Mind Control, Mind Games, Hypnotism And BrainwashingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1138)

- Sleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningFrom EverandSleep Stories for Adults: Overcome Insomnia and Find a Peaceful AwakeningRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (3)

- Raising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsFrom EverandRaising Good Humans: A Mindful Guide to Breaking the Cycle of Reactive Parenting and Raising Kind, Confident KidsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessFrom EverandMindset by Carol S. Dweck - Book Summary: The New Psychology of SuccessRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (328)

- A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsFrom EverandA Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI, and the Five Breakthroughs That Made Our BrainsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)