Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1-3. Organizational Legitimacy Under Conditions of Complexity The Case of The Multinational

Uploaded by

tndgo75Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1-3. Organizational Legitimacy Under Conditions of Complexity The Case of The Multinational

Uploaded by

tndgo75Copyright:

Available Formats

Organizational Legitimacy under Conditions of Complexity: The Case of the

Multinational Enterprise

Author(s): Tatiana Kostova and Srilata Zaheer

Source: The Academy of Management Review , Jan., 1999, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Jan., 1999), pp.

64-81

Published by: Academy of Management

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/259037

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Academy of Management is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

The Academy of Management Review

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

I Acadenmy of Management Review

1999, Vol. 24. No. 1, 641- 81.

ORGANIZATIONAL LEGITIMACY UNDER

CONDITIONS OF COMPLEXITY: THE CASE OF

THE MULTINATIONAL ENTERPRISE

TATIANA KOSTOVA

University of South Carolina, Columbia

SRILATA ZAHEER

University of Minnesota

We examine organizational legitimacy in the context of the multinational enterprise

(MNE). After discussing three types of complexity (of the legitimating environment, the

organization, and the process of legitimation) that MNEs typically face, we explore

their effects on MNE legitimacy. In particular, we distinguish between the legitimacy

of the MNE as a whole and that of its parts, and we develop propositions that include

issues of internal versus external legitimacy and positive and negative legitimacy

spillovers.

It has become a growing industry to critique Nike a whole or at its subunits? What constitutes the

globally (Phil Knight, NBC Today Show, May 11,

legitimating environment of an MNE operating

1998).

in multiple institutional environments? What is

One of the critical issues faced by multina- the relationship between the overall legitimacy

tional enterprises (MNEs) involves the establish- of the MNE and the legitimacy of its subunits?

ment and maintenance of legitimacy in their And, finally, why do MNEs find it so difficult to

multiple host environments. Instances of legiti- establish and maintain legitimacy and so often

macy problems in MNEs abound, ranging from experience crises of legitimacy?

censure of MNEs in the global media, such as Research on organizational legitimacy (e.g.,

that faced by Nike for its labor practices in Asia D'Aunno, Sutton, & Price, 1991; Dowling & Pfef-

(Maitland, 1997; Marshall, 1997), to direct attacks fer, 1975; Meyer & Scott, 1983; Scott, 1987, 1995)

on MNE operations, such as the destruction of provides us with a theoretical foundation on

Cargill's facilities in India (Dewan, 1994). In an which to examine these questions. Scholars

even more extreme example, Shell was accused have defined organizational legitimacy as the

of conspiring with the Nigerian government to acceptance of the organization by its environ-

execute Ken Saro-Wiwa, who had led a cam- ment and have proposed it to be vital for organ-

paign against its environmental practices (New- izational survival and success (Dowling & Pfef-

burry & Gladwin, 1997). fer, 1975; Hannan & Freeman, 1977; Meyer &

An examination of the MNE case suggests that Rowan, 1977). Institutional theorists have identi-

not only is legitimacy a critical issue for MNEs fied some of the determinants of organizational

but that current research leaves several ques- legitimacy and the characteristics of the legiti-

tions on organizational legitimacy unaddressed. mation process (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Powell &

For instance, what exactly is the legitimacy of a DiMaggio, 1991; Scott, 1995; Selznick, 1957;

complex organization such as an MNE, and Zucker, 1983), citing three sets of factors that

where does it reside: at the level of the MNE as shape organizational legitimacy: (1) the environ-

ment's institutional characteristics, (2) the or-

ganization's characteristics, and (3) the legiti-

We thank Eric Abrahamson, Jeff Arpan, Jean Boddewyn, mation process by which the environment

Joe Galaskiewicz, Kendall Roth, Mike Russo, Aks Zaheer, the builds its perceptions of the organization

participants of the AMR theory development workshop, the

(Hybels, 1995; Maurer, 1971).

participants of the Freeman International Economics Semi-

In this article we suggest that examining the

nar at the Hubert Humphrey Institute of the University of

Minnesota, and the reviewers of AMR for their comments MNE case can potentially extend theories of or-

and suggestions. ganizational legitimacy since the MNE chal-

64

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1999 Kostova and Zaheer 65

lenges some of the underlying assumptions be- dia (e.g., Financial Times or CNN) and global

hind these theories. The MNE is an organization activist groups (e.g., Greenpeace). The legiti-

that operates in two or more countries with mul- macy of the MNE subunit is its acceptance by the

tiple subunits linked through shared policies or specific host country institutional environment.

strategy.' As such, MNEs introduce an element In this article we examine both the legitimacy of

of complexity in all three factors that influence the MNE as a whole and the legitimacy of the

organizational legitimacy-in the legitimating MNE subunit and discuss the relationships be-

environment, the organization, and the process tween them. We suggest that they are interrelat-

of legitimation. We suggest that these complex- ed-that is, the legitimacy of the MNE as a

ities have significant implications for theories of whole is affected by the legitimacy of its sub-

organizational legitimacy, since they affect the units, and vice versa. However, MNE legitimacy

nature of legitimacy, and the process of legiti- may not be a simple average of the legitimacy of

mation. Therefore, the MNE case can both ad- its subunits.

vance our understanding of organizational le- Several of our propositions are unique to the

gitimacy in general and shed light on the MNE because they are based on characteristics

specific legitimacy-related difficulties experi- of the MNE that represent differences "in kind"

enced by MNEs. from domestic organizations (Ghoshal & West-

Traditionally, researchers have examined le- ney, 1993). These propositions could be thought

gitimacy at two levels: (1) at the level of classes of as elements of a theory of MNE legitimacy. A

of organizations (Carroll & Hannan, 1989; Han- few propositions, however, apply both to MNEs

nan & Freeman, 1977; Meyer & Rowan, 1977; and to complex domestic organizations, for they

Singh, Tucker, & House, 1986) and (2) at the or- are based on characteristics of the MNE that

ganizational level (Ashforth & Gibbs, 1990; Co- represent differences "in degree" (Ghoshal &

valeski & Dirsmith, 1988; Deephouse, 1996; Dowl- Westney, 1993) from domestic organizations.

ing & Pfeffer, 1975; Neilsen & Rao, 1987; Ritti & These latter propositions are not unique to the

Silver, 1986; Suchman, 1995). Here, we adopt the MNE and serve, therefore, to expand our theories

latter approach and examine legitimacy at the of organizational legitimacy.

level of the organization, which we call organi- We distinguish between the legitimacy of an

zational legitimacy. MNE and two proximal concepts from the MNE

Organizational legitimacy can further be ex- literature: (1) overcoming entry barriers and

amined at the level of the MNE as a whole, as (2) cultural adaptation. While a lack of legiti-

well as at the level of the subunit of the MNE in macy may act as a barrier to entry, legitimacy

a particular country. The legitimacy of the MNE issues go beyond market entry and can be-

as a whole is the acceptance and/or approval of come salient at any point in a company's his-

the MNE (not necessarily of any particular sub- tory, as we have seen in such cases as Shell

unit) by its legitimating environment. For the and Nike. Further, although cultural adapta-

MNE as a whole, the legitimating environment tion of an organization to a particular host

is the global "meta-environment" (Zaheer, country may contribute to its legitimacy, it is

1995a), which consists of all of its home and host neither a necessary nor a sufficient condition

country institutional environments as well as for legitimacy because of the many other fac-

supranational institutions, such as global me- tors involved, including the nature of the prod-

uct, and regulatory issues. In addition, legiti-

macy is socially constructed. Thus, there may

1 Currently, the most accepted definition of the MNE is

not be a one-to-one correspondence between

that it is a specific organizational form that

an organization's cultural adaptation and the

comprises entities in two or more countries, regardless

way it is perceived by the environment. There-

of legal form and fields of activity of those entities,

which operates under a system of decision-making per- fore, it is possible for an MNE to be culturally

mitting coherent policies and a common strategy adapted and still lack legitimacy in a partic-

through one or more decision-making centers, in which ular environment.

the entities are so linked, by ownership or otherwise,

In this article we also do not specifically ex-

that one or more of them may be able to exercise a

significant influence over the activities of the others,

amine the political processes or the negotia-

and in particular, to share knowledge, resources, and re- tions between MNEs and host governments, as

sponsibilities with others (Ghoshal & Westney, 1993: 4). many scholars in international business have

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

66 Academy of Management Review January

done (Behrman & Grosse, 1990; Doz, 1986; Doz & who opposed the project on the grounds that it

Prahalad, 1980; Dunning, 1993; Fagre & Wells, was the first step toward a "new colonization" of

1982; Kobrin, 1987; Lecraw, 1984; Murtha & Len- India by the West (Dewan, 1994). The farmers

way, 1994; Vernon, 1971), which could affect the claimed that the seeds project would take away

legitimacy of firms directly-in the regulatory their traditional self-sufficiency in seed produc-

domain-or indirectly-through the social con- tion, leave them dependent on multinational

struction engaged in by political interest firms, and lead to their financial distress and

groups. We focus, instead, on the background economic exploitation-apart from destroying

factors that could facilitate or hinder such firm- their traditional way of life. The tension in-

state negotiation processes. creased to the point that some of Cargill's of-

In summary, we address the extent of the chal- fices and warehouses in India were vandalized

lenge encountered by MNEs in establishing and and burned down by angry farmers.

maintaining organizational legitimacy in the Meanwhile, Cargill had launched a project in

face of complexity in the environment, in the Kandla, in western India, to build a 1-million-ton

organization, and in the process of legitimation. export-oriented salt extraction and processing

As an illustration of the issues MNEs can face in facility. This project also experienced legiti-

their quest for legitimacy, we start with a brief macy problems. Various local groups vocifer-

description of Cargill's problems in India and ously opposed the project, ranging from environ-

use this case (and others) to discuss the critical- mentalists to local salt producers, who felt

ity of legitimacy for MNEs, as well as the effects threatened by multinational competition, to pol-

of complexity on legitimacy. We then develop iticians, who categorized this project as another

propositions and conclude with a discussion of step toward a neocolonization of India. For their

implications for theory and practice. arguments, these groups drew from history and

from the symbolism of Mahatma Gandhi's pro-

test march against the salt tax imposed by the

CARGILL IN INDIA

British in 1942. The politicians attempted to sug-

Cargill, Inc.,2 is perhaps the world's largest gest that foreign colonizers, once again, were

private agricultural company, with 65,000 em- threatening the country's economic freedom.

ployees and annual sales of over $50 billion, as "Salt, once the symbol of our freedom move-

well as a presence in over 65 countries. Cargill ment, is today a pointer to our economic serf-

entered the Indian market initially to create and dom" (V. P. Singh, Member of Parliament, quoted

distribute new high-quality hybrid seeds in Ban- in Setalvad, 1993: 85). Although Cargill took sev-

galore in South India, and subsequently to build eral steps to moderate the criticism-for exam-

a salt extraction and processing facility in west- ple, by moving toward more labor-intensive

ern India. Its establishment in India has been technology that would protect employment-it

marked by a series of crises that illustrate the finally withdrew from this project. We believe

critical importance of establishing and main- that the legitimacy problems faced in India

taining legitimacy for MNEs and their subunits. were not unrelated to Cargill's withdrawal.

Briefly, Cargill's seeds project in Bangalore

experienced difficulties from the very begin-

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND

ning. This project was a response to the Indian

PROPOSITIONS

government's new Seed Policy, introduced in

September 1988, which sought "to upgrade Institutional theory suggests that organization-

seeds and provide the Indian farmer with the al legitimacy is shaped by three sets of factors:

best planting material in the world so as to (1) the characteristics of the institutional envi-

optimize his output" (Pania, 1992: 82). The com- ronment, (2) the organization's characteristics

pany, at its inception, encountered substantial and actions, and (3) the legitimation process by

resistance from local farmers, encouraged by which the environment builds its perceptions of

influential local politicians and intellectuals the organization (e.g., Hybels, 1995, and Maurer,

1971). In this section we use the MNE to discuss

how organizational legitimacy is affected when

there is complexity in these three sets of factors.

2 This section draws entirely on publicly available docu-

mentation and video material. We suggest that a higher level of complexity in

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1999 Kostova and Zaheer 67

any of these factors-the institutional environ- perspectives (Berger & Luckman, 1967; Stryker &

ment, the organization, and the process of legit- Statham, 1985) suggests that this interaction is a

imation-makes it more difficult for organiza- complex social and cognitive process, subject to

tions to establish and maintain their legitimacy. bounded rationality. Therefore, the process of

We develop formal propositions on the relation- legitimation, which involves the continuous

ship between complexity in these factors and testing and redefinition of the legitimacy of the

the legitimacy challenges faced by MNEs and organization through ongoing interaction with

illustrate these propositions with examples from the environment (Baum & Oliver, 1991), is likely

Cargill and other firms. to be a boundedly rational process. The impli-

Organizational theorists long have recog- cations of the complexity of this process for or-

nized that institutional environments are com- ganizational legitimacy become particularly ap-

plex and fragmented since they consist of mul- parent in the MNE, since in this case both the

tiple task environments (Galbraith, 1973; organization and the legitimating environment

Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967; Thompson, 1967), mul- may lack the information and the cognitive

tiple institutional "pillars" (Scott, 1995), multiple structures required to understand, interpret, and

resource providers (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978), and evaluate each other. Table 1 presents a sum-

multiple stakeholders (Evan & Freeman, 1988). mary of the types of complexities that emerge in

Drawing from this research and from the MNE the three factors that influence legitimacy when

case, we suggest that the complexity of the in- one examines the MNE case, and it briefly sum-

stitutional environment is reflected in two major marizes the consequences of these complexities

aspects. First, institutional environments are for organizational legitimacy.

fragmented and composed of different domains In the rest of this section we develop proposi-

reflecting different types of institutions: regula- tions that address the ease or difficulty of estab-

tory, cognitive, and normative (Scott, 1995). lishing and maintaining legitimacy at two lev-

Second, MNEs conduct operations in mul- els of analysis: (1) the MNE as a whole and (2) the

tiple countries that may vary with respect to MNE subunit. We consider the establishment of

their institutional environments and, thus, are legitimacy as particularly relevant for the MNE

exposed to multiple sources of authority subunit when it enters a new country. Maintain-

(Sundaram & Black, 1992). ing legitimacy, however, is relevant both for the

Organizational researchers also have noted MNE as a whole and for the MNE subunit. We

that organizations themselves can be complex also discuss the extent to which each of the

and fragmented, for they may consist of multiple propositions is unique to the MNE or is applica-

subunits with varying levels of interdependence ble to all organizations. A summary of the prop-

and independence (Ghoshal & Bartlett, 1990; ositions is graphically presented in Figure 1.

Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967). This type of complex-

ity is particularly apparent in MNEs where the

Environmental Complexity and Legitimacy

organization is fragmented not only by function

or task but also by geographical region and The complexity of the MNE environment is

location. As a result, each of the different sub- reflected in the multiple domains of the institu-

units of the MNE faces its own host institutional tional environment and in the multiplicity of

environments, which vary across countries with institutional environments faced by MNEs.

respect to legitimacy requirements. In addition, Multiple domains of the institutional environ-

organizations form their own internal institu- ment. Organizational theorists have suggested

tional environments with their own legitimacy that institutional environments consist of a va-

requirements over time (Selznick, 1957). Thus, riety of institutions, including regulations, cul-

each organizational subunit of the MNE is faced tural norms, educational systems, and so on.

with the task of establishing and maintaining Researchers have suggested that there are dif-

both external legitimacy in its host environment ferent types of legitimacy that reflect the differ-

and internal legitimacy within the MNE (Rosen- ent types of institutions operating in the envi-

zweig & Singh, 1991; Westney, 1993). ronment, such as sociopolitical, cognitive, and

Finally, research on the interaction between pragmatic legitimacy, among others (Aldrich &

organizations and the environment from the so- Fiol, 1994; Boddewyn, 1995; Hannan & Carroll,

cial construction and symbolic interactionism 1992; Suchman, 1995). Although we acknowledge

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

68 Academy of Management Review January

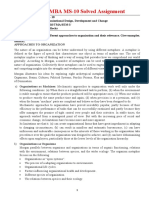

TABLE 1

Legitimacy-Related Complexities Faced by MNEs

Factors Influencing

Legitimacy Types of Complexity Description Effects on Legitimacy

Institutional Multiple domains of the Institutional environments The tacitness of the cognitive

environment institutional environment consist of three types of and normative domains

domains-the regulatory, the presents a particular

cognitive, and the challenge to MNEs as they

normative-all of which seek legitimacy.

influence legitimacy.

Many and varied country MNEs face at least as many The larger the number of

institutional environments different institutional countries, the larger the

environments as the number variance in the legitimacy

of countries in which they requirements that MNEs have

operate, since institutions to deal with. However, the

tend to be country specific. larger the number of

Their number and variety countries, the more likely that

pose specific challenges to the organization has

MNE legitimacy. developed competence in

dealing with different

institutional environments.

Institutional distance between This is the difference or The greater the institutional

home and host environments similarity between the distance, the more difficult it

regulatory, cognitive, and will be for the MNE to

normative institutional understand the host

environments of the home and environment and its

the host countries of an MNE. legitimacy requirements.

Further, the greater the

institutional distance, the

higher the need will be to

adapt organizational practices

to meet host country

legitimacy requirements.

Organization MNE subunits face two Legitimacy is required in both Tension between internal and

institutional environments: institutional environments external legitimacy

(1) the external host country since the survival of the MNE requirements can make

environment and (2) the subunit is contingent on achieving external legitimacy

internal environment of the support from the parent difficult for a subunit.

MNE. company and from the host

country.

Process of Bounded rationality and the Owing to the social and Foreignness presents challenges

legitimation liability of foreignness cognitive nature of the to legitimacy because of (1) the

legitimation process, the lack of information about the

acceptance of an MNE subunit MNE on behalf of the host

is affected by the host environment, (2) the use of

environment's perception of stereotypes and different

and attitude toward foreign standards in judging foreign

firms. firms, and (3) the use of MNEs

as targets for attacks by

interest groups in the host

country.

Legitimacy spillovers from Owing to the bounded ration- Under conditions of bounded

outside and within the ality of the legitimation rationality, the environment

organization process, the legitimacy of a makes sense of the legitimacy

particular unit is not of a given unit based on the

independent of all other units legitimacy of other similar

to which it is cognitively units-for example, other

related. units of the same organization

or classes of organizations to

which the focal unit belongs.

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1999 Kostova and Zaheer 69

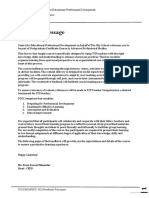

FIGURE 1

Complexity and MNE Legitimacy: Summary of Propositions

P1. Regulatory/cognitive/

normative domains

Environmental P2 Number and variety of

complexity countries

.> | P3. Institutional distance

MNE subunit

\ \ t ~~~~Challenge to

\ ~~~ < ~~ establishing

P4. External versus internal and maintaining

Organizational legitimacy legitimacy

complexity P5. Geocentric/polycentric/

ethnocentric orientation

P6. Liability of foreignness

P7. Visibility and size of MNE MNE

Complexity of the P8 Legitimacy of local firms

legitimation process P9. Legitimacy of other parts of Challenge to

the MNE maintaining

PIO. Legitimacy of classes of

organizations

the existence of multiple domains of the institu- The cognitive pillar draws from social psy-

tional environment, in this article we treat the chology (Berger & Luckman, 1967) and the cog-

legitimacy of an organization or of an organiza- nitive school of institutional theory (Meyer &

tional subunit as holistic in nature (i.e., there is Rowan, 1977; Zucker, 1983). Organizations have

one overall legitimacy of an organizational to conform to or be consistent with established

unit), even though it may be afffected by the cognitive structures in society to be legitimate.

different domains of the institutional environ- In other words, what is legitimate is what has a

ment in which the organization functions. "taken for granted" status (Aldrich & Fiol, 1994;

We draw from institutional theory (Meyer & Suchman, 1995) in society.

Rowan, 1977; Scott, 1995; Zucker, 1983) to suggest The normative pillar goes beyond regulatory

a set of institutional domains based on the three rules and cognitive structures to the domain of

pillars of institutional environments suggested social values (Selznick, 1957). Organizational le-

by Scott (1995): the regulatory, the cognitive, and gitimacy, in this view, accrues from congruence

the normative. The regulatory pillar is com- between the values pursued by the organization

posed of regulatory institutions-that is, the and wider societal values (Parsons, 1960). It is

rules and laws that exist to ensure stability and "the degree of cultural support for an organiza-

order in societies (North, 1990; Streek & Schmit- tion," which, presumably, will result from such

ter, 1985; Williamson, 1975, 1991). Organizations congruence in values (Meyer & Scott, 1983: 201).

have to comply with the explicitly stated re- The three domains are not necessarily inde-

quirements of the regulatory system to be legit- pendent. Values, for instance, may drive cogni-

imate, although they do have the ability, partic- tive categorization and, in turn, influence and be

ularly in the long run, to influence the regulatory influenced by regulation. The cognitive and nor-

domain through interest intermediation (Murtha mative domains emerge through processes of

& Lenway, 1994). education and socialization, and the regulatory

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

70 Academy of Management Review January

domain, in particular, is influenced by govern- process, which may not have been that transpar-

ments and the interest intermediation process ent to an MNE coming into the country. These

(Murtha & Lenway, 1994). hidden values were reflected in such comments

Cargill's problems with the salt project illus- as "agriculture is not a market, it is a lifestyle"

trate a variety of legitimacy issues associated and "a self-sufficient community will become

with these domains, such as the cognitive issue wage-laborers of the multinationals"-expres-

of Cargill being a privately held multinational sions by some of the groups opposing the seeds

and the symbolic meaning of salt in India, the project (Dewan, 1994). Cargill was able to deal

normative issue of protecting manual labor and with the more explicit regulatory requirements

traditional agricultural lifestyles, and the regu- (e.g., those related to environmental issues), but

latory issue of whether Cargill could be given it appeared to have had much greater difficulty

permission to operate on land owned by the Port in understanding and dealing with the norma-

Authority of Kandla. Inability to meet the mini- tive domain. We propose, therefore:

mum requirements for legitimacy on any of

these dimensions could jeopardize the overall Proposition 1: The cognitive and nor-

legitimacy of the project, and of the firm, in mative domains of the institutional

India.

environment will present a greater

The three domains of country institutional en-

challenge to MNE subunits in estab-

vironments-the regulatory, cognitive, and nor-

lishing their legitimacy, and to MNEs

mative-differ in their degree of formalization

and MNE subunits in maintaining le-

and tacitness-that is, the degree to which they

gitimacy, compared to the regulatory

are explicitly codified and the ease with which

domain.

observers (especially outside observers such as

a foreign company) can make sense of them. The

Multiplicity of institutional environments. By

regulatory domain is perhaps the easiest to ob-

definition, MNEs face multiple country institu-

serve, understand, and interpret correctly be-

tional environments, each with its own set of

cause it is formalized in laws, rules, and regu-

regulatory, cognitive, and normative domains

lations. Compared to the regulatory domain, the

(Westney, 1993). The structure and the composi-

normative domain is more tacit and part of the

tion of these institutions, and their legitimacy

"deep structures" of a country (Gersick, 1990). It

requirements, typically vary across national en-

is, therefore, more difficult to sense and to inter-

vironments (Kogut, 1991; Kostova, 1996). For ex-

pret, particularly for an outsider. The cognitive

ample, most rules and regulations tend to be

domain perhaps lies between the regulatory

country specific, since they are created by gov-

and the normative domains, as to the degree to

ernments and are often the outcome of local

which it can be observed and interpreted cor-

political processes. So are the cognitive and nor-

rectly.

This suggests that legitimacy in the norma- mative institutions (the shared social knowl-

tive and cognitive domains, rather than in the edge and the values, beliefs, and social norms),

regulatory domain, might pose a more difficult which are shaped through the educational sys-

challenge for MNEs. After an MNE subunit has tem and through processes of social interaction,

conducted operations in a host environment for typically within national borders. Cargill, with

some time, it may become easier for it to make operations in 65 countries, has faced 65 unique

sense of local cognitive and normative institu- sets of regulatory, cognitive, and normative in-

tions. So will the hiring of "locals" to manage stitutions that it has had to get to know, under-

the operation (rather than posting expatriates), stand, and take into account in its operations.

or working with a local partner. However, we Such multiplicity and variety in the environ-

believe that the cognitive and normative do- ments in which they operate clearly differenti-

mains will always be relatively more challeng- ate MNEs from domestic firms (Sundaram &

ing than the regulatory domain to MNE subunits Black, 1992).

trying to establish or maintain their legitimacy. In addition to the number of countries in

In both of Cargill's projects in India, for in- which an MNE operates, its legitimacy is also

stance, there were many deeply embedded so- likely to be affected by the extent of variety

cial values that played a role in the legitimating across these environments. The more similar the

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1999 Kostova and Zaheer 71

institutional profiles' (Kostova, 1997) of the mul- MNEs with mature international operations fac-

tiple countries in which it operates, the easier it ing dozens of institutional environments may

will be for the MNE to make sense of all of its find it easier to gain legitimacy compared to

environments and to respond appropriately to smaller or newer organizations that lack the or-

their legitimacy requirements. For example, ganizational capability required for establish-

MNEs operating in a set of countries in Asia ing legitimacy. However, operating in a multi-

alone will find it easier to establish their legit- plicity of environments may also present a

imacy in all of those countries than will MNEs challenge to maintaining legitimacy, because it

operating in countries with different institu- makes it more likely that the firm faces legiti-

tional profiles-say, in a set that includes Asian macy issues in one or the other of those environ-

and European countries. In brief, the legitimacy ments, and this illegitimacy spills over to the

of a given organization is "negatively affected rest of the MNE.

by the number of different authorities sovereign We suggest, therefore, that the effects on le-

over it and by the diversity or inconsistency of gitimacy of the number and variety of countries

their accounts of how it is to function" (Meyer & of operation will be different for establishing

Scott, 1983: 202). legitimacy from maintaining legitimacy. It will

As suggested by institutional theorists, organ- be easier for the "IBMs" (the more experienced

izations may achieve legitimacy by becoming international companies with many varied sub-

"isomorphic" with the institutional environ- units) to enter a new environment and establish

ment-that is, by adopting organizational forms, the legitimacy of their subunits there, because

structures, policies, and practices that are simi- of their reputation, experience, and bargaining

lar to the ones institutionalized in their environ- power. However, it might be more difficult for

ment (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Meyer & Rowan, such MNEs and MNE subunits to maintain their

1977). In an MNE, given the multiplicity and va- legitimacy, because they will be more suscepti-

riety of institutional environments and the ble to problems caused by spillovers of illegiti-

cross-country differences between these envi- macy from any of the other MNE subunits. Thus:

ronments, achieving legitimacy through isomor-

Proposition 2: The greater the number

phism becomes a difficult, if not impossible,

and variety of countries in which an

task (Westney, 1993). However, MNEs do manage

MNE operates, the less of a challenge

to achieve legitimacy in seemingly conflicting

its subunits face in establishing their

multiple institutional environments; they do not

legitimacy in a particular host coun-

necessarily adapt to the local environments in

try, but the greater the challenge the

such cases but, rather, manage their legitimacy

MNE as a whole and its subunits face

through negotiation with their multiple environ-

in maintaining their legitimacy.

ments (Doz & Prahalad, 1980; Fagre & Wells,

1982; Lecraw, 1984; Oliver, 1991). Another important effect of the variety of in-

Operating in a large number of countries and stitutional environments that MNEs operate in is

a wide variety of environments suggests that a the institutional distance between the home and

firm has extensive organizational experience in the host country. The institutional distance be-

dealing with legitimacy issues and expertise in tween two countries, defined as the difference/

scanning different institutional environments, similarity between the regulatory, cognitive,

identifying important legitimating actors, mak- and normative institutions of the two countries

ing sense of their legitimacy requirements, and (Kostova, 1996), will affect both the difficulty of

negotiating with them. It also suggests that the understanding and correctly interpreting local

firm may have significant bargaining power institutional requirements, as well as the extent

with regard to the states and governments it of adjustment required. This is due to the fact

deals with (Kobrin, 1987; Lecraw, 1984), particu- that organizational structures, policies, and

larly in the regulatory domain. Thus, large practices tend to reflect the institutional envi-

ronment in which they have been developed

and established (Kogut, 1993). Thus, it will be

easier for an MNE to understand and adjust to

3The institutional profile of a country is characterized by

the set of regulatory, cognitive, and normative institutions the legitimacy requirements of a country that is

established in the country. institutionally similar to its home country than

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

72 Academy of Management Review January

of one that is institutionally distant from the Lorsch, 1967), but there has been relatively little

home country (e.g., a U.S. MNE in Canada versus discussion on the implications of this fragmen-

China). This effect of institutional distance on tation for organizational legitimacy. For exam-

legitimacy operates at the level of the MNE sub- ple, each subunit faces its own legitimacy is-

unit. Therefore, we propose the following: sues, and, further, its legitimacy is both

influenced by and influences the legitimacy of

Proposition 3: The greater the institu-

tional distance between the home the whole organization. We discuss these effects

country of an MNE and a particular in greater depth in the section on legitimacy

host country, the greater the chal- spillovers.

lenge an MNE subunit will face in es- Here, we focus on one particular issue related

tablishing and maintaining its legiti- to organizational complexity and legitimacy: the

macy in that host country. need for organizational subunits to achieve in-

ternal legitimacy within the organization in ad-

Propositions 2 and 3 apply primarily to

dition to legitimacy with the external environ-

MNEs and not to purely domestic firms. Al-

ment (Westney, 1993). We define internal

though some variance between local institu-

legitimacy as the acceptance and approval of

tions is possible (especially in large and di-

an organizational unit by the other units within

verse countries like the United States), this

the firm and, primarily, by the parent company.

within-country institutional variance is likely

Similar to external legitimacy, internal legiti-

to be much smaller than between-country vari-

ances. Moreover, each country, regardless of macy is important for the survival of an organi-

how big and diverse it is internally, usually zational subunit because of its dependence on

has country-wide institutions that supersede other subunits and on the parent for continuing

local institutions and can be used in case a access to organizational resources such as cap-

conflict arises between local institutional re- ital and knowledge (Pfeffer & Salancik, 1978).

quirements. For example, if a regulation in We believe that the MNE case illustrates how

California is different from a regulation in considerations of internal legitimacy can con-

Minnesota and a conflict occurs as a result of strain a subunit's efforts to achieve external le-

this, there probably exists an institutional gitimacy.

mechanism at the federal level that will rec- Internal legitimacy is likely to result from a

oncile the differences. When national borders unit's adoption of the organization structures,

are crossed, however, as in the case of MNEs, policies, and practices institutionalized within

the between-country differences in their mul- the MNE. These structures, policies, and prac-

tiple institutional environments might be sub- tices tend to be imprinted by the external insti-

stantial-and the institutional requirements of tutional environment in which the organization

different countries contradictory. In addition, was founded (Kogut, 1993). Therefore, in purely

there are very few institutional mechanisms

domestic firms, internal legitimacy require-

that have supranational jurisdiction to solve

ments are likely to be similar to or at least con-

potential conflicts (Sundaram & Black, 1992).

sistent with external legitimacy requirements.

In MNEs, internal legitimacy requirements may

differ substantially from the external legitimacy

Organizational Complexity and Legitimacy requirements in a host country, especially when

there is high institutional distance between

By definition, complex organizations such as

home and host countries (Kostova, 1997). In such

MNEs are not monolithic, unitary entities. They

tend to be complex social systems consisting of cases adaptation to the external institutional

different activities, product divisions, and loca- requirements can result in internal inconsis-

tions, which are integrated and interdependent tency (Rosenzweig & Singh, 1991). For example,

to various extents (Bartlett, 1986; Bartlett & Cargill's willingness to move to labor-intensive

Ghoshal, 1991; Prahalad & Doz, 1987; Rosen- technology for its salt operations in India pre-

zweig & Singh, 1991). Organizational theorists sented a significant departure from its global

have recognized the fragmentation of complex strategy of using highly automated technolo-

organizations (Fligstein, 1990; Lawrence & gies. Thus:

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1999 Kostova and Zaheer 73

Proposition 4: MNE subunits will face Complexity in the Legitimation Process

a greater challenge, compared to sub-

We now address the legitimacy issues that

units of purely domestic firms, in estab-

arise from complexity in the legitimation pro-

lishing and maintaining legitimacy in

cess. Legitimation-that is, the process through

their host environment because of the

which legitimacy is achieved (Hybels, 1995;

increased potential for conflict that they

Maurer, 1971)-is largely sociopolitical and cog-

face between the requirements for in-

nitive in nature. Both the organization and the

ternal versus external legitimacy.

environment are involved in the legitimation

process, in which the organization's legitimacy

However, the tradeoff between internal and

is continuously tested and redefined. In this pro-

external legitimacy may not necessarily cause

cess the organization attempts to make sense of

illegitimacy, since certain characteristics of the

the legitimacy requirements of the institutional

MNE may, themselves, moderate the problem.

environment by observing, learning, interpret-

Research in international management distin-

ing, and even influencing those requirements

guishes between different types of MNEs, based

(Doz & Prahalad, 1980; Weick, 1993). The legiti-

on their mindsets, mentalities, and strategies. As

mating environment also tries to make sense of

suggested by Perlmutter (1969), some MNEs are

the organization and to evaluate its acceptabil-

"geocentric," in that they develop a global, cos-

ity.

mopolitan orientation that is not tied to any par-

Because of its social and cognitive nature, the

ticular national identity. Others are "ethnocen-

process of legitimation is complex, imperfect,

tric," in that their identity is strongly rooted in

and boundedly rational (March & Simon, 1958),

the home country. "Polycentric" MNEs develop a especially in the case of MNEs, where both the

multiplicity of identities to reflect each of the organization and the legitimating environment

countries they operate in. may lack the information necessary to correctly

The orientation of the MNE will affect the ex- understand, interpret, and evaluate each other.

tent of tension between internal and external We suggest that these characteristics of the le-

legitimacy. Geocentric MNEs will be able to re- gitimation process affect MNE legitimacy by in-

spond successfully to the multiple institutional fluencing the environment's perceptions of the

requirements in different countries by adopting MNE, as captured in the "liability of foreign-

supranational structures, policies, and practices ness," as well as in the phenomenon of "legiti-

that are legitimate worldwide. The adoption of macy spillovers."

such globally acceptable policies will also en- Liability of foreignness. Firms doing business

sure internal consistency. Polycentric MNEs may abroad face certain costs that purely domestic

also find it relatively easy to manage the ten- firms do not-that is, they face a liability of

sion between internal and external legitimacy, foreignness (Hymer, 1960; Zaheer, 1995b; Zaheer

because they are used to internal inconsistency & Mosakowski, 1997), which can arise for a va-

in their efforts to adapt to each local environ- riety of reasons. Here, we focus on the cognitive

ment. Ethnocentric MNEs, however, will experi- aspects of the liability of foreignness, as re-

ence the greatest difficulty in managing this flected in the lack of information about the MNE

tension, for their practices and policies are not on the part of the host country environment, the

derived from universal principles, nor are they use of stereotypes and different standards in

accustomed to internal variety. Formally: judging MNEs versus domestic firms, and the

use of MNEs (especially large and visible MNEs)

Proposition 5: The extent of the chal- as targets for attack by host country interest

lenge faced by MNE subunits in estab- groups.

lishing and maintaining internal and The host country legitimating environment

external legitimacy will be moderated typically has less information with which to

by the orientation of the parent com- judge an MNE entrant. This could result in de-

pany; it will be easier for subunits of lays in legitimation, in continuing suspicion to-

geocentric and polycen tric MNEs, ward the MNE, and in scrutiny of the MNE to a

compared to subunits of ethnocentric much greater extent than that of domestic firms.

MNEs. In addition, the lack of information on a partic-

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

74 Academy of Management Review January

ular MNE may lead to the use of stereotypical are the larger, better-known MNEs, since they

judgments based on the legitimacy or illegiti- can provide the most publicity and visibility for

macy of certain classes of organizations to the interest groups. The cases of Nike, Shell, and

which the MNE is perceived to belong. The ste- Cargill illustrate this liability of being large and

reotypes used to judge MNEs may arise from visible.

long-established, taken-for-granted assump- Thus, although size may provide power in

tions in the host environment regarding MNEs in market activities, such as in obtaining a con-

general, or of MNEs from a particular industry or tract with a local supplier or the local govern-

a particular home country (say, for example, the ment, it is perhaps a source of vulnerability in

suspicion that existed in the 1980s of Japanese nonmarket activities4 (Baron, 1994), such as the

real estate holdings in the United States). The maintenance of legitimacy. While this would

case of Cargill also illustrates these points. apply, to some extent, to all large firms-

Cargill's arrival in India was equated with the whether MNEs or purely domestic-we suggest

arrival of the British colonialists. "The metaphor that MNEs are more vulnerable to these types of

really is colonization," "They have come like the attacks, for several reasons. First, MNEs operate

British," and "Leave our seeds alone" were all in multiple institutional environments with

comments made about Cargill by local interest varying regulatory, cognitive, and normative

groups (Dewan, 1994). standards. This provides opportunities for inter-

Another aspect of the liability of foreignness est groups to identify practices used by the firm

is the different legitimacy standards that some in some country that may be unacceptable in

institutional environments hold for MNEs com- another country and to use those as a rallying

pared to domestic firms. MNEs are expected, in point. Further, such attacks are more difficult to

many countries, to do more than local compa- counter because distance and language barri-

nies in building their reputation and goodwill, ers make it difficult for the public to ascertain

in supporting local communities, in protecting the facts. Thus, large and visible MNEs are par-

the environment, and so on. Shell, for example, ticularly susceptible to legitimacy attacks from

claims that it has contributed much more to the interest groups. Formally:

people of Nigeria and the local community of

Proposition 7: Larger and more visible

Ogoniland than any other company in the re-

MNEs and their subunits will find it a

gion, but it still has been subject to fierce criti-

greater challenge than will smaller

cism both in Nigeria and internationally (New-

and less visible MNEs and their sub-

burry & Gladwin, 1997). Similarly, the standards

units to maintain legitimacy, because

against which Nike's labor practices are held in

they are more vulnerable to attacks

China are quite different from the standards

from interest groups.

that would be applied in judging a local shoe

manufacturer. This leads us to the following: Although, in general, multinational firms are

subject to the liability of foreignness as re-

Proposition 6: MNE subunits will find

flected in Propositions 6 and 7, there could exist

it a greater challenge to establish and

specific situations in which being an MNE

maintain legitimacy in their host en-

brings with it an initial level of legitimacy,

vironments, compared to domestic

rather than illegitimacy. Such situations could

firms, because of the stereotyping and

arise in environments in which local firms have

different standards applied to foreign

lost their legitimacy because of an economic,

firms by the host environment.

political, or social cataclysm (e.g., in Eastern

Further, MNEs can become the target of differ-

ent interest groups in the host countries, which

may attack the legitimacy of these companies 4Market activities include "those interactions between

for political reasons and not because of any the firm and other parties that are intermediated by markets

evidence of wrongdoing (Maitland, 1997). Inter- or private agreements. These interactions typically are vol-

untary and involve economic transactions and the exchange

est groups can campaign against MNEs simply

of property," whereas nonmarket activities are those that are

to gain political clout or to gain publicity as a "intermediated through public institutions," typically do not

socially conscious political force. Under these involve economic transactions or property exchange, and

conditions, the MNEs most likely to be targeted may be voluntary or involuntary (Baron, 1994: 1).

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1999 Kostova and Zaheer 75

Europe or, more recently, in Indonesia). The re- it is likely that its legitimacy would be judged

sulting public awareness of local firms' mis- based on inferences drawn from such classes of

deeds-whether it be links with organized crime organizations as "other Western firms in Indo-

or charges of nepotism and corruption-serves nesia," "other foreign shoe makers in Indone-

to legitimate nonlocal firms. The illegitimacy of sia," and "Brazilian firms" in general. These

local firms also could arise in countries that judgments may also be influenced by the envi-

have protected local business to the point that ronment's knowledge about that firm's subunits

the absence of competition has made them in- in other countries.

sensitive to their customers and the public, as We call this phenomenon a legitimacy spill-

well as in countries where there exists a long- over and suggest that, although valid for all

standing sense of inferiority and xenophilia. In types of organizations, legitimacy spillovers are

such cases it is possible that all local firms lack particularly salient for MNEs. Legitimacy spill-

legitimacy and, as a result, almost any nonlocal overs can come from different sources and oc-

firm is immediately perceived as more legiti- cur in different directions. There can be positive

mate. Thus: spillovers, which contribute to legitimacy, and

negative spillovers, which hurt legitimacy. Pos-

Proposition 8: The less legitimate local

itive and negative spillovers may not be com-

firms are in a particular institutional

pletely symmetric in their effects, in that nega-

environment, the less challenge MNE

tive spillovers are likely to have a stronger

subunits will face in establishing and

effect on legitimacy than will positive spill-

maintaining legitimacy in that host

overs. The fact that a particular subunit is legit-

environment.

imate does not necessarily add much to the le-

Legitimacy spillovers. We suggest that as a gitimacy of other subunits or of the organization

result of the complexity inherent in the social, as a whole. However, the illegitimacy of any

cognitive, and boundedly rational nature of the subunit is likely to hurt the legitimacy of other

legitimation process, the legitimacy of a given subunits and of the organization. The collapse of

organizational unit in a particular environment BCCI (Bank of Credit and Commerce Interna-

is not independent of the legitimacy of other tional) worldwide, because of its problems in

organizational entities with which the unit is Britain and the United States, illustrates the po-

cognitively related. As has been shown in cog- tentially strong effects of negative spillovers.

nitive psychology, people make sense of social We distinguish between internal spillovers,

events by categorizing them on the basis of such which occur within an organization, and exter-

cognitive structures as schemas and stereotypes nal spillovers, which occur between organiza-

(e.g., Markus & Zajonc, 1985). Further, under con- tions. Internal spillovers reflect the interdepen-

ditions of bounded rationality, people's judg- dence in legitimacy across subunits within an

ments about particular events are affected by organization. They can happen vertically-that

their judgments about similar events that fall is, between the subunit and the MNE as a

into the same cognitive category-a phenome- whole-or horizontally-that is, across sub-

non often referred to as the "representativeness units. Vertically, the parent firm's reputation

heuristic" (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974). There- could affect the legitimacy of its subunits (Fom-

fore, it is likely that when an institutional envi- brun, 1996), and vice versa. For example, with

ronment judges the legitimacy of a particular the Southeast Asian subsidiaries of Nike expe-

organizational unit, it will refer to the legitimacy riencing problems with the image of their labor

of other organizational units that are similar to practices, the legitimacy of Nike as a whole is

the focal unit, since they belong to the same being questioned. Horizontally, a firm's illegiti-

cognitive category-for example, to the same macy in one subunit (e.g., Cargill's seeds project

class of organizations. in India) can have a negative impact on the

Thus, the legitimacy of a foreign subsidiary of legitimacy of its other subunits (Cargill's salt

an MNE may be judged based on the legitimacy project in India). Thus, we offer the following:

of all subsidiaries of that MNE or of all subsid-

iaries of the same home country in that host Proposition 9: MNE subunits will face

country. For example, if a Brazilian shoe manu- a greater challenge in establishing

facturer were to open an operation in Indonesia, and maintaining legitimacy when the

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

76 Academy of Management Review January

MNE as a whole or any of its other (illegitimacy) of other organizations

subunits experiences legitimacy prob- belonging to the same organizational

lems; similarly, the MNE as a whole classes; these legitimacy spillover ef-

will also face a greater challenge in fects will be particularly strong for

maintaining legitimacy if any of its MNE subunits at'the time of entry into

subunits experiences legitimacy prob- a new host country.

lems.

External spillovers reflect interdependence in DISCUSSION

legitimacy between organizations belonging to

In this article we have focused on MNEs be-

the same classes, such as those from the same

cause they provide a unique context in which to

home country or industry. For example, once

extend existing theories of organizational legit-

there is a precedent for a Japanese auto maker

imacy, as well as to develop elements of a the-

to start operations in the United States, it be-

ory of MNE legitimacy. We have explored three

comes easier for other Japanese auto makers to

types of complexity illustrated by the MNE case

do likewise. Historically shared perceptions

(in the legitimating environment, in the organ-

about certain countries or regions in a particular

ization, and in the process of legitimation)

host country can also influence the legitimacy of

and developed propositions on the extent of the

any firm from that country (e.g., Israeli firms in

challenge faced by MNEs and their subunits in

the Middle East or Russian firms in the former

establishing and maintaining legitimacy. Al-

Eastern Bloc).

though some of these complexities (in particu-

Spillover effects are likely to be particularly

lar, environmental complexity) have been recog-

strong in the initial period of establishing the

nized by scholars (e.g., Boddewyn, 1995; Evan &

legitimacy of a new subsidiary (rather than

Freeman, 1988; Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967; Scott,

while maintaining it), when both the subsidiary

1995; Thompson, 1967), their implications for or-

and the legitimating environment operate under

ganizational legitimacy rarely have been ex-

conditions of bounded rationality. On the one

plicitly examined.

hand, the subsidiary lacks knowledge about the

With regard to the effects of environmental

institutional environment-its requirements

complexity, we have explored the influence of

and its legitimating actors-and, thus, is limited

the normative and cognitive institutional do-

in its ability to achieve legitimacy by adapting

mains and the greater challenge they present to

to or negotiating with the institutional environ-

MNE legitimacy than does the regulatory do-

ment. On the other hand, the legitimating actors

main. As for organizational complexity, we have

in the local environment lack knowledge about

suggested that subunits of geocentric or

the particular subsidiary and may make initial

polycentric MNEs will be better placed to man-

judgments about its legitimacy based on infer-

age the tension between internal and external

ences from other similar subsidiaries or from the

legitimacy than will subunits of ethnocentric

parent MNE's reputation (Fombrun, 1996; Fom-

MNEs. Finally, exploring the boundedly rational

brun & Shanley, 1990). As time passes, the sub-

nature of the legitimation process has led us to

sidiary is likely to learn about the institutional

understand why, for instance, MNEs might suf-

environment and how to deal with it, and the

fer from a liability of foreignness in their accep-

local environment is also likely to accrue infor-

tance by the environment, why large and visible

mation about the particular subsidiary and be-

organizations are particularly vulnerable to at-

gin to judge it more correctly. As a result, the

tack by political interests, and why complex or-

dependence on inferences from analogs may de-

ganizations are vulnerable to legitimacy spill-

crease. This proposition is congruent with the

overs, both from within and outside.

ideas of inertia and time dependence of legiti-

This article contributes to theories of organi-

macy (Singh et al., 1986):

zational legitimacy because the MNE presents

Proposition 10: The extent of the chal- an extreme example that pushes the boundaries

lenge faced by an MNE or an MNE of these theories in areas that have been over-

subunit in establishing and maintain- looked in the past. For instance, the MNE exam-

ing its legitimacy will be negatively ple suggests multiple levels of organizational

(positively) related to the legitimacy legitimacy: in complex organizations there are

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1999 Kostova and Zaheer 77

clearly issues of the legitimacy of the whole tutional distance between home and host

organization, as well as of its parts. The legiti- countries and the liability of foreignness, par-

macy of the whole organization is not necessar- ticularly at market entry, apply only to the

ily simply the average legitimacy of its parts, MNE case.

although legitimacies at the two levels clearly When we speculate on the role of legitimacy

are related. The tension between internal and in MNEs and other complex organizations, we

external organizational legitimacy, while more must bear in mind some issues. Perhaps the

apparent in the MNE case, also applies, to some most troubling question-one that becomes

extent, to all complex organizations. Finally, the particularly salient as we consider the diffi-

case of the MNE reveals the social and cognitive culties likely to be faced by MNEs in their

nature of the legitimation process and its quest for legitimacy in their multiple host en-

bounded rationality. For example, the MNE case vironments-is why MNEs need to be legiti-

pushes us to think about how positive and neg- mate at all in all of their different environ-

ative legitimacy spillovers may occur within an ments. While researchers traditionally have

organization as well as between organizations. assumed that legitimacy is required for access

This article also presents the first steps to-

to resources, and for survival, the answer may

ward building a theory of MNE legitimacy. Al- not be that simple. It is possible for organiza-

though some aspects of MNE legitimacy can

tions not to be wholly legitimate and still be

be accommodated by general theories of or-

profitable-even survive over the long term-

ganizational legitimacy, there are certain

especially if, as is often the case with MNEs,

characteristics of MNEs that are different

they have alternative sources of resources and

enough to call for a distinct approach. To start

organizational support. There is also the ques-

with, the sheer number and, more important,

tion of MNE legitimacy over time. Although

the possibility of extreme variety across the

over time MNEs may become more like domes-

multiple institutional environments that MNEs

tic organizations in terms of their legitimacy

confront create legitimacy issues not faced by

(Zaheer & Mosakowski, 1997), the problem for

purely domestic firms. The overall legitimacy

MNEs is that they cannot afford to become

of an MNE may be affected to a greater extent

complacent. MNEs are much more vulnerable

by some host environments than by others. For

to cross-border legitimacy spillovers than are

instance, environments with the strictest legit-

purely domestic firms. Legitimacy, therefore,

imacy requirements may be most critical (e.g.,

may take on a more "punctuated" quality in

BCCI lost its overall legitimacy from problems

MNEs compared to the stable, inertial charac-

in Britain and the United States-not in its

ter of legitimacy in purely domestic firms.

home countries of Abu-Dhabi and Luxem-

These issues would clearly benefit from em-

bourg). In addition, the existence of multiple

pirical research.

environments with varying legitimacy stan-

dards creates greater opportunities for inter- With this article we hope to begin a conver-

est groups to attack MNEs and MNE subunits sation on aspects of organizational legitimacy

and to question their legitimacy. Further, the that are brought to the surface when we exam-

tension between the MNE's internal legitimacy ine complexity in the environment, in the or-

requirements, which are imprinted by the ganization, and in the process of legitimation.

home country legitimating environment Clearly, this is just a beginning, for much more

(Kogut, 1993), and the legitimacy requirements conceptual work is needed on exploring im-

of its subunits' host countries is likely to cre- portant issues that we have not addressed

ate difficulties for the subunits- difficulties here. Some of the most interesting issues

purely domestic firms will not have. However, worth exploring further are the question of the

these challenges to external legitimacy will contingencies that moderate the importance of

be moderated by the parent MNE's interna- a particular type of complexity and the ques-

tional orientation-whether geocentric, tion of the possible interactions between them

polycentric, or ethnocentric. Finally, the that may have serious implications for the

boundedly rational nature of the legitimation challenges organizations face in achieving or-

process creates special problems for MNEs. ganizational legitimacy. We believe that the

For instance, the effects on legitimacy of insti- ideas we introduce in this article can serve as

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

78 Academy of Management Review January

a basis for such future theoretical develop- even more important, have strategies in place to

ments. deal with legitimacy spillovers and crises. Fur-

The propositions we present here are test- ther, managers of MNEs need to pay attention to

able, especially if one uses approaches to the all three domains of legitimacy-especially the

measurement of organizational legitimacy more tacit normative and cognitive domains.

that recently have begun to emerge in the lit- They also need to recognize the tradeoff be-

erature. Deephouse (1996), for instance, codes tween internal and external legitimacy and the

public media reports to gauge the legitimacy benefits of creating a geocentric or polycentric

of an organization, and this type of textual orientation within the MNE to reduce the tension

analysis could be used to establish legiti- between the two. Managers of MNEs need to be

macy, as well as to identify the sources of aware, too, of the stricter legitimacy standards

legitimacy problems, such as in which institu- to which MNEs are held, and of the legitimacy

tional domain a problem had its origins. The risks related to size and visibility.

propositions on the maintenance of legitimacy As for legitimacy spillovers, MNEs can try to

are particularly amenable to testing with buffer themselves in the public eye from organ-

these methods, since the loss of legitimacy is izational classes that are likely to jeopardize

often a "critical incident" around which the their legitimacy, and they can deliberately iden-

textual analysis can be organized. tify with more legitimate organizations. Since

A downside of these methods, especially positive and negative spillovers may also accu-

cross-nationally, arises from both language mulate over time, a firm might build up a repu-

problems and from the fact that the media do not tation for being legitimate and use this buffer to

operate by the same norms across countries on counter a potential loss of legitimacy in the fu-

what they report. A solution to this problem may ture-akin to the notion of building a stock of

be to examine a matched sample of foreign and "moral capital."5 An example of an MNE subunit

domestic firms in the same country. Assessing that has been successful in building moral cap-

the ease or difficulty of establishing and main- ital to overcome the negative views of Japanese

taining legitimacy, or the tension between inter- subsidiaries in the United States is Toyota's U.S.

nal and external legitimacy, is best done subunit. This subsidiary has taken pains to com-

through surveys of international division man- municate to the American public-through cor-

agers and/or foreign subunit managers in large porate advertising-its espousal and support of

MNEs. Some of the propositions (e.g., Proposi- quintessentially American causes. This exam-

tions 9 and 10 on legitimacy spillovers) may lend ple also illustrates the fact that MNEs need not

themselves more readily to traditional popula- only to build a good track record but also to

tion ecology methods. Propositions regarding in- clearly communicate that record to the legiti-

stitutional distance can be operationalized by mating environment because of the socially con-

adapting constructs measuring the characteris- structed nature of organizational legitimacy.

tics of different institutional environments (Kos-

tova, 1997).

REFERENCES

Our discussion of legitimacy issues in the

MNE has significant practical implications. By Aldrich, H., & Fiol, C. M. 1994. Fools rush in? The institutional

context of industry creation. Academy of Management

identifying the factors that cause difficulty in

Review, 19: 645-670.

establishing and maintaining legitimacy, we

Ashforth, B., & Gibbs, B. 1990. The double-edge of organiza-

have given practitioners the basis for proac-

tional legitimation. Organization Science, 1: 177-194.

tively managing the legitimacy of their organi-

Baron, D. 1994. Integrated strategy: Market and nonmarket

zations, instead of simply responding to legiti-

components. Working paper, Graduate School of Busi-

macy crises as they occur in a "trial and error"

ness, Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA.

manner. Some specific practical recommenda-

Bartlett, C. 1986. Building and managing the transnational:

tions include, but are not limited to, the follow-

The new organizational challenge. In M. Porter (Ed.),

ing. MNEs need to continuously monitor legiti- Competition in global industries: 367-404. Boston: Har-

macy in all national environments and must not vard Business School Press.

become complacent about legitimacy in any of

them. They need to design strategies to respond

to varied legitimacy requirements and, perhaps 'We are indebted to Joe Galaskiewicz for this idea.

This content downloaded from

203.249.102.25 on Tue, 01 Mar 2022 07:53:41 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1999 Kostova and Zaheer 79

Bartlett, C., & Ghoshal, S. 1991. Global strategic manage- Fombrun, C. 1996. Reputation: Realizing value from the cor-

ment: Impact on the new frontiers of strategy research. porate image. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Guest Editor's comments, Special Issue on Global Strat-

Fombrun, C., & Shanley, M. 1990. What's in a name: Reputa-

egy. Strategic Management Journal, 12: 5-16.

tion building and corporate strategy. Academy of Man-

Baum, J., & Oliver, C. 1991. Institutional linkages and organ- agement Journal, 33: 233-258.

izational mortality. Administrative Science Quarterly,

Galbraith, J. 1973. Designing complex organizations. Read-

36: 187-218. ing, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Behrman, J. N., & Grosse, R. 1990. International business and Gersick, C. 1990. Revolutionary change theories: A multi-

governments: Issues and institutions. Columbia, SC: Uni- level exploration of the punctuated equilibrium para-

versity of South Carolina Press. digm. Academy of Management Review, 31: 9-41.

Berger, P., & Luckman, T. 1967. The social construction of Ghoshal, S., & Bartlett, C. 1990. The multinational corpora-

reality. New York: Doubleday. tion as an interorganizational network. Academy of

Boddewyn, J. 1995. The legitimacy of international-business Management Review, 15: 603- 625.

political behavior. International Trade Journal, IX: 143- Ghoshal, S., & Westney, E. 1993. Introduction. In S. Ghoshal &

161. E. Westney (Eds.), Organization theory and the multina-

tional corporation: 1-23. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Carroll, G., & Hannan, M. 1989. Density dependence in the

evolution of populations of newspaper organizations. Hannan, M., & Carroll, G. 1992. Dynamics of organizational

American Sociological Review, 54: 524-541. populations: Density, competition, and legitimation.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Covaleski, M., & Dirsmith, M. 1988. An institutional perspec-

tive on the rise, social transformation, and fall of a Hannan, M., & Freeman, J. 1977. The population ecology of

university budget category. Administrative Science organizations. American Journal of Sociology, 83: 929-

Quarterly, 33: 562-587. 984.

D'Aunno, T., Sutton, R., & Price, R. 1991. Isomorphism and Hybels, R. C. 1995. On legitimacy, legitimation and organi-

external support in conflicting institutional environ- zations: A critical review and integrative theoretical

ments: A study of drug abuse treatment units. Academy model. Best Paper Proceedings of the Academy of Man-

of Management Journal, 34: 636-661. agement: 241-245.

Deephouse, D. 1996. Does isomorphism legitimate? Academy Hymer, S. 1960. The international operations of national

of Management Journal, 39: 1024-1039. firms. (Doctoral dissertation, published in 1976.) Cam-

bridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dewan, M. 1994. Patent pending: Indian farmers fight to

retain freedom of their seeds. Film, South View Produc- Kobrin, S. J. 1987. Testing the bargaining hypothesis in the

tions. manufacturing sector in developing countries. Interna-

tional Organization, 41: 609-638.

DiMaggio, P., & Powell, W. 1983. The iron cage revisited:

Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in Kogut, B. 1991. Country capabilities and the permeability of

organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48: borders. Strategic Management Journal, 12: 33-47.

147-160. Kogut, B. 1993. Learning, or the importance of being inert:

Dowling, J., & Pfeffer, J. 1975. Organizational legitimacy: So- Country imprinting and international competition. In

cial values and organizational behavior. Pacific Socio- S. Ghoshal & E. Westney (Eds.), Organization theory and