Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Seppuku Tradition

Uploaded by

Malvika JayakumarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Seppuku Tradition

Uploaded by

Malvika JayakumarCopyright:

Available Formats

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigō Takamori: Samurai, "Seppuku", and the Politics of

Legend

Author(s): MARK J. RAVINA

Source: The Journal of Asian Studies , AUGUST 2010, Vol. 69, No. 3 (AUGUST 2010), pp.

691-721

Published by: Association for Asian Studies

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40929189

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Association for Asian Studies is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to The Journal of Asian Studies

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Journal of Asian Studies Vol. 69, No. 3 (August) 2010: 691-721.

© The Association for Asian Studies, Inc., 2010 doi:10.1017/S0021911810001518

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigõ Takamori: Samurai,

Seppuku, and the Politics of Legend

MARKJ. RAVINA

According to standard reference works, the Meiji leader Saigõ Takamori com-

mitted ritual suicide in 1877. A close reading of primary sources, however,

reveals that Saigõ could not have killed himself as commonly described;

instead, he was crippled by a bullet wound and beheaded by his followers.

Saigo's suicide became an established part of Japanese history only in the

early 1900s, with the rise of bushidõ as a national ideology. By contrast, in

the 1870s and 1880s, the story of Saigo's suicide was just one of many fantastic

accounts of his demise, which also included legends that he ascended to Mars or

escaped to Russia. Remarkably, historians have treated Saigo's suicide as an

unproblematic account of his death, rather than as a legend codified some

four decades later. This essay links the story of Saigõ s suicide to the rise of

modern Japanese nationalism, and examines other Saigõ legends as counternar-

rativesfor modern Japan.

September 24, 1877, Saigo Takamori, the leader of a massive rebellion

against the new national government of Japan, died on the hills of Shiroyama

in Kagoshima. His demise was suffused with tragic irony: Saigõ died fighting a

government he had helped to create. Saigõ was a central figure in the movement

to overthrow the shogunate, and, after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, he emerged

as one of the three most powerful men in the new Meiji state. But Saigõ grew

increasingly estranged from his colleagues and resigned from the government

in 1873. In his final years, during a period of tectonic cultural change, he was

celebrated as a model of traditional samurai virtue. In January 1877, Saigõ

assumed command of a rebellion started by his impulsive followers and led an

army of roughly 20,000 disgruntled samurai northeast toward Tokyo. The

failure of the rebellion was obvious by April, but the rebels, retreating through

the mountains of Kyushu, managed to evade the advancing imperial army for

another five months.

Saigõ s death was a resonant historical moment, replete with powerful, con-

tradictory expectations. More than the death of a single individual, his tragic end

represented the death of the samurai class. The failure of Saigõs rebellion,

Mark J. Ravina (mark.ravina@eiTiory.edu) is Professor of History at Emory University.

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

692 Mark J. Ravina

known as the Satsuma Rebellion in English and the War of the Southwest (Seinan

senso) in Japanese, foreclosed the possibility that samurai would ever recover

their hereditary privileges, such as stipends and a monopoly on government

offices. For the government and its supporters, this was a moment of celebration:

it was described as a triumph of the forces of reason and progress over backward-

ness and "feudalism." Outside the government, however, Saigõs death marked

the end of the exhilarating, if frenzied, sense of possibility that suffused early

Meiji politics. Among both intellectuals and the general public, Saigõ

represented an alternative to a statist, bureaucratic, and centralizing vision of

modern Japan. An implausible range of critics, from proponents of Rousseau s

social contract to defenders of samurai tradition, identified with Saigõ s rebellion

and mourned his death as a triumph of autocracy. His heroic stature as a leader

of the Restoration, and his fierce reticence about his own dissenting views,

combined to make Saigõ a symbol for all forms of principled resistance to the

Meiji state. His death, therefore, represented the end of an era of revolutionary

possibilities.

This was a heavy symbolic burden, and the quotidian details of Saigõ s last

days and death could not convey such powerful expectations. Thus, when

artists and commentators depicted Saigõs rebellion and defeat, they produced

a rich body of fantasies and legends. Some envisioned Saigõ, or at least his

head, ascending to the heavens and lodging in the planet Mars (see figure 1,

Seinan chinbun). These stories were prompted, in part, by the close proximity

of Mars to Earth in 1877: Mars was especially bright in the night sky that year,

aiding the discovery of the Martian moons Phobos and Deimos in August

1877. Others depicted Saigõ, reclining peacefully, attaining nirvana while sur-

rounded by weeping disciples (see figure 2, Saigõ nehan zõ). This print was a

visual quote from a long tradition of Buddhist painting and sculpture, except

that Saigõ took the place of Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha. An opposite

vision was a fanciful print entitled Saiga's Revolution in the Netherworld

showing Saigõ, a powerful rebel to the last, overthrowing the King of Hell (see

figure 3, Takamori Myõfu daikaikaku).

Also popular was the story that Saigõ, surrounded by his followers, com-

mitted seppuku, or ritual samurai suicide. A tabloid print from October 11,

1877, for example, shows Saigõ plunging his sword into his abdomen; blood

spurts from his belly just above a cartouche with his name (see figure 5, Shir-

oyama Saigõ shoshõ seppuku no zu). Behind him, Oku Yoshinosuke, his

second (kaishaku), waits to cut off his head. Saigõ is surrounded by loyal fol-

lowers, who, despite serious wounds, continue to fight until the end. The title

of the print, Saigõ and His Officers Commit Seppuku at Shiroyama, reinforces

the visual message.

Tales of Saigõ s seppuku have enjoyed remarkable longevity and popularity.

The spectacular suicide scene in the Warner Brothers film The Last Samurai,

for example, is among the latest, and certainly the most expensive, depictions

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigõ Takamori 693

Figure 1. Seinan chinbun (Mffi^Hfl) by Baido Kunimasa (ffè^HIIE),

printed in Tokyo in July 23, 1877. Kagoshima City Museum of Art.

of Saigo s seppuku. l Mentions of Saigo s seppuku or suicide also appear in major

Japanese and American historical reference books, including the one-volume

lrThe connection between Katsumoto and Saigo is explained by the director, Edward Zwick, at the

film s website. "First in college and then for years after, I read a great deal of Japanese history. ... I

was deeply moved by Ivan Morris's The Nobility of Failure, which tells the story of Saigõ Takamori,

one of Japans most famous figures, who first helped create and then rebelled against the new gov-

ernment. His beautiful and tragic life became the point of departure for our fictional tale" (Warner

Brothers 2004).

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

694 MarkJ. Ravina

Figure 2. Saigo nehan zo (WWMMt) by Nagashima Mosai (tMI^S1), printed in

Tokyo in October 5, 1877. Kagoshima City Museum of Art.

Columbia Encyclopedia (2000), the one-volume Kadokawa Nihonshi jiten

(Takayanagi and Takeuchi 1974), the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (1983),

and both major multivolume encyclopedias of Japanese history: the Kokushi dai-

jiten (1979-97) and Nihonshi daijiten (1992). Saigõ s suicide is also noted in

several major American textbooks on Japan, including Andrew Gordons A

Modern History of Japan (2003) and Peter Duus's Modern Japan (1998), as

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigõ Takamori 695

Figure 3. Takamori Myofu daikaikaku ($kËèKfàJz$c£) by Suzuki Kunimoto (ièfiïH

Ä), printed in Tokyo on December 10, 1877. Collection of Sheldon and Heather Siegal.

Figure 4. Shiroyama saigo no kessen (^cPjUlS^&Uc) by Yamazaki Toshinobu (lililí

if), printed in Tokyo in October, 1877. Collection of the author.

well as the two major Japanese-language biographies of Saigo by academic

historians (Inoue 1970; Tamamuro 1960).

The story of Saigõ s seppuku is often juxtaposed with fantastic legends of his

death. Ivan Morris, for example, in his influential Nobility of Failure, wrote that

Saigõ "bowed in the direction of the Imperial Palace and cut open his stomach."

This heroic death helped inspire amazing stories of Saigõ s valor, including "the

fantastic legend according to which Saigõ would reappear in 1891 on a Russian

warship in order to rescue his country from foreign danger" (Morris 1975, 267,

273). In their study of early Japanese newspapers, The Birth of the News

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

696 MarkJ. Ravina

(Nyüsu no tanjo), Kinoshita Naoyuki and Yoshimi Shun'ya contrasted the associ-

ation of Saigõ and Mars with the seemingly objective details of his death: "rumors

of the appearance of a 'Saigõ star* had already become a topic of popular conver-

sation before Saigõ stabbed himself to death (jijin) on September 24th" (1999,

229).

These juxtapositions are misleading. Saigõ s seppuku is merely another Saigõ

legend, not an empirically grounded account of his death. Saigõ did not "cut open

his stomach" or "stab himself to death." These tales of suicide, like stories of

Saigõs ascent to Mars, were attempts to represent the enormous implications

of Saigõs death. If, for example, Saigõ was the last true samurai, then he

needed a spectacular and iconic death. What is fascinating about Saigõs

seppuku is how it has morphed into something else: a standard account of

Saigõ s demise, reproduced in reference works and textbooks.

How and why did this happen? The transformation of Saigõ s seppuku from

fantasy to history coincided with the rise of bushidõ as a national ideology. Con-

necting Saigõ to bushidõ allowed ideologues both inside and outside the Meiji

state to embed him in a longer narrative of Japanese martial heroes. A glorious

death by seppuku also meant that critics could both venerate Saigõ and criticize

his insurrection: a proper suicide ensured that Saigõ was dead, but honorably

dead. This was a fitting end for a man who was both a leader of the Restoration

and a major threat to the Meiji state. The legend of Saigõ s seppuku was thus most

amenable to late Meiji nationalism and its emphasis on bushidõ. Seppuku turned

Saigõ into a forerunner of Japanese militarism, rather than a dangerous challen-

ger to the state.

My purpose in this essay is thus twofold. First is a narrow empirical project:

demonstrating that tales of Saigõs "suicide" are speculative, if not blatantly false.

Second is a broader inquiry into the politics of historiography. Cultural critics

such as Ivan Morris and Kawahara Hiroshi (1971) have connected Saigõ

legends to recurrent tropes in Japanese history. Morris, for example, invoked

Saigõ as an example of the Japanese love of stalwart and principled but

doomed heroes: the nobility of failure. My biography of Saigõ includes a pre-

liminary exploration of the legends of Saigõ s death (2004, 1-12, 206-14), and

Ikai Takaakis recent essay (2004) explores the politics of Saigõ lore in the

1870s. The present essay is an attempt to show how Saigõ legends, over

decades, were rewritten in accordance with changing political positions and

visions of Japanese history. Exponents of Saigõ s "suicide" used this act to link

him with a lineage of Japanese heroes. Saigõ, in this narrative, was great

because of his connection to a Japanese warrior tradition. In their enthusiasm

for this project, Saigõ s biographers produced increasingly detailed and implausi-

ble accounts of Saigõ s seppuku. At the same time, the canonization of Saigõ s

suicide as "fact" has generated a curious distinction. Rather than treat Saigõs

suicide and, for example, his ascent to Mars as rival legends, we have treated

the former as an event and the latter as myth. In doing so, we have, however

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigõ Takamori 697

unwittingly, reproduced a nationalistic and militaristic interpretation of Saigo and

marginalized alternative visions of Saigõ and of Japan.2

Heroes and Heroic Deaths

How did Saigõ die? Because so many eyewitnesses died themselves in the

of Shiroyama, there are no surviving firsthand accounts. Saigõ s last mome

last words thus will remain a subject of fascination and speculation. Yet the surv

records are sufficient to arrive at a negative conclusion: Saigõ did not cut h

abdomen, and it is implausible that he sat erect in a formal suicide ritual. W

establish this through forensic evidence: three independent accounts o

body. One is from the diary of Kawaguchi Takesada, an accountant with the

Japanese Army. Kawaguchi s observations are detailed and clinical, almost a

of an accountants mind-set. His account of Saigõs death is terse and detac

When our troops (soldiers from each brigade) approached from all s

and breached the rebel stronghold, all the rebel leaders (Saigõ Takam

Kirino Toshiaki, etc.) were already dead. A summary follows:

Saigõ Takamori: shot through the hip, head missing, later recovered

Kirino Toshiaki: head and face ripped apart, many sword wounds.

Murata Shinpachi, Beppu Shinsuke, Henmi Jürota, Ikegami Shirõ, T

shiro Jüji, Iwamoto Heihachi, Hirano Masasuke, Ishizuka Chõsae

Gamo Hikojirõ, Katsura Shirõ, Yamanoda Hikosuke, etc., total of

people. The rebels were all clad in red loincloths (fundoshi) and

were wearing [traditional] Japanese clothes. (Kawaguchi [1878]

2:356-57)

Kawaguchi noted that Kirino had many sword wounds, but reported n

Saigõ, besides the gunshot wound to the hip and his missing head.

A parallel account is found in a letter by John Capen Hubbard, a ship

providing noncombat military support for Mitsubishi. As the captain of a

ship, Hubbard watched the final assault on the rebels from the deck of h

and arrived on the scene soon after the rebels had been defeated. In a letter

wife, he described Saigõ s corpse:

When we arrived we found eight bodies laid out in two rows. The f

was Saigo. He was a large powerful looking man, his skin almost wh

His clothing had been taken off and he lay there naked. It was

"Charles Yates treats Saigo legends in passing, but dismisses them as distractions from t

story of Saigõ, arguing that "one cannot find the real man in what his countrymen hav

about him" (1994, 425; see also Yates 1995, 1-14, 173-86).

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

698 Mark J. Ravina

seconds before I realized his head was cut off. Next to Saigo lay Kirino,

then Murata. Saigõ s was the only headless body, but the others were a

fearful sight to look at. Their heads were dreadfully cut up and it was

quite evident that they killed each other. No doubt their heads would

all have been cut off by their own people had time permitted. While

looking at the bodies, Saigõs head was brought in and placed by his

body. It was a remarkable looking head and any one would have said at

once that he must have been the leader. (Nock 1948, 372-75)

Hubbards account differs from Kawaguchis in small points of detail. For

example, was Saigõs corpse naked, or still wearing a red loincloth? On the

central point of Saigõs injuries, however, both accounts agree: Kirino was

covered with sword wounds, but Saigõ had none. Hubbard, notably, conjectured

that Murata and Kirino had killed each other, but not Saigõ. He made no refer-

ence to seppuku or to an abdominal wound consistent with ritual suicide.

Finally, Saigõs injuries are confirmed by the governments autopsy report

(shitai kensasho). This document describes Saigõs body as follows:

Clothing: Pale yellow striped unlined summer kimono, blue gaiters

Injuries: Head severed from body. Shot from the right femur through

the bone to the left. Old sword wound on bone of right forearm.

Hydrocele.

This medically detailed account notes Saigõ s childhood sword wound as well as

his hydrocele, an accumulation of fluid in the testicles as a result of a parasitic

infection.3 It makes no mention, however, of any sword wounds to the abdomen.

Can this forensic evidence be reconciled with stories of suicide or jisatsu? If,

by suicide, we mean causing one s own death, then Saigõ did not commit suicide.

The proximate cause of Saigõ s death was decapitation, and it is difficult to image

him cleanly cutting off his own head. Nor did Saigõ stab himself to death (jijin) or

cut open his abdomen: he had no abdominal or stab wounds. The question of

seppuku is more complex. Since Saigõs day, the term seppuku has had two

primary meanings.4 First, it referred to ritual suicide by cutting open ones

abdomen. This is the literal meaning of the component characters "cut" and

"belly," and this interpretation is reflected in the quotes from Morris and from

Kinoshita and Yoshimi earlier. Seppuku could also refer to an early modern

form of execution reserved for samurai. This was a formal proceeding, distin-

guished from ordinary executions by rules of etiquette. Commonly, the

3For a detailed account of Saigõ s death certificate and reports of his death, see Murakami Sumio

(1995) and Mori Shigeyoshi (1984).

^hese two meanings of seppuku have been remarkably consistent over the past century. The defi-

nition of seppuku in the 1889 dictionary Genkai (Õtsuki [1889] 2004), for example, lists these two

meanings. These are also the two primary definitions of seppuku in the 1974 Kokugo daijiten.

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigö Takamori 699

condemned bathed, dressed in white, and sat upright in front of a small stand

bearing a dagger. As the accused reached forward to grasp the weapon, the

kaishaku would cut off his head. Only rarely did convicts actually cut themselves.

In some instances, self-injury was impossible: they were provided with wooden

dirks or fans rather than actual weapons. In such "fan seppuku" executions

(o gibara), the emphasis was on facing death with calm resolution and on ritual

process rather than self-injury (Chiba 1991, 153-84; Ikegami 1995, 253-57).

Many accounts of Saigõ s death feature this form of seppuku. Perhaps the earliest

is a vivid print from October 1877 (see figure 5, Saigõ shoshõ seppuku no zu). The

nishikie shows Saigõ sitting upright in the posture associated with seppuku. He

has removed his coat, an Imperial Army uniform, and has pulled open his shirt to

expose his abdomen. His left hand rests on his belly, while the other hand holds a

short sword. Murata Shinpachi, one of Saigõs loyal followers, stands behind him

with a long sword, drawn and ready, at the level of Saigõ s neck. The Imperial

Army is seen advancing from the left, but Saigõ s men are burning paper and wet

clothes to create a smokescreen. This image emphasizes Saigõs stalwart courage

but does not show him actually cutting his own abdomen. A similar depiction of

formal seppuku appears in Mushanokõji Saneatsus biography of Saigõ, known in

English through a 1942 translation by Sakamoto Moriaki. In Mushanokõjis

account, Saigõ, shot in the thigh and abdomen, called Beppu to his side and declared,

"comrade, this would be a good place." Saigõ then sat up, quietly composed himself,

and bowed toward the east to show respect for the emperor. Beppu apologized to his

master and cleanly severed his head (Mushanokõji 1938, 455-57).

Such a formal seppuku would not have left an injury to Saigõ s abdomen. But

these accounts of Saigõ s "seppuku" still sit uneasily with forensic evidence. The

government s autopsy report explains that a bullet passed through Saigõ s thigh

and femur, so the bullet would likely have shattered Saigõs femur, making it

Figure 5. Saigo shosho seppuku no zu (W»i£##JffilËl) by Matsuzuki Hosei (&£{£

IÄ), printed in Tokyo on October 11, 1877. Ryõzen rekishikan.

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

700 Mark J. Ravina

impossible for Saigõ to sit or walk without help - what is colloquially described as

a "broken hip" is actually a break in the upper femur near the hip socket. Saigõ s

severely swollen scrotum would have further limited his ability to sit upright.

Indeed, Saigõs hydrocele and advanced heart disease were so severe that by

1877, he often had trouble walking under normal circumstances. Given his inju-

ries and general physical condition, it is difficult to envision how Saigõ could have

gotten to his knees and sat erect without assistance. Saigõ could have been pulled

to a sitting posture by his comrades and held in place, but this undignified vision

is not found in any Japanese Saigõ legend.

In short, we can speak of Saigö s seppuku only under a narrow range of

hypothetical conditions. If the gunshot wound to the femur did not hit the

femoral artery, and if Saigõ s thigh muscles were robust (despite likely atrophy

from advanced angina and hydrocele), and the break in the femur was simple

rather than compound, then Saigõ, with support from compatriots, might have

been able to hold himself briefly in a sitting position. Perhaps such an act

could fit within an expansive definition of seppuku. But it utterly improbable

that Saigö could have managed the regal carriage and calm demeanor that

appear in period images and later biographies.

The nishikie artists of the 1870s who depicted Saigõ s death, however, were

unconcerned with physiological accuracy, or even plausibility. Rather, they were

interested in producing suitably spectacular images of Saigõ. Depictions of

Saigõs seppuku were, like accounts of his descent to hell or ascent to the

heavens, metaphorical and evocative rather than empirical.5 Indeed, nishikie

artists were largely unconcerned with the internal coherence of their prints.

Although nishikie sometimes quoted from newspaper accounts, the cartouches

and the images were often unrelated or even contradictory. Figure 5, Saigõ

and His Officers Commit Seppuku (Saigõ shoshõ seppuku no zu), for example,

is strikingly internally inconsistent. The text describes not Saigõs suicide, but

the courage of an Imperial Army officer, Yasumura Harutaka, who tried to

take Saigõ alive and succeeded in stripping him of his pistol. In the image,

however, Saigõ is committing seppuku, there is no pistol, and Yasumura is

unable to reach Saigõ because a rebel samurai blocks his way. Figure 4

(Shiroyama saigo no kessen) is only slightly less confused. The text describes

how a police officer named Yasumura almost reached Saigõ, but that Saigõ

managed to get off one shot, slightly wounding him. Saigõ, Kirino, Murata,

Ikegami, Beppu, and other key officers then committed suicide. The image,

however, shows no gun, no one named Yasumura, and only Saigõ is

committing seppuku.

Such tensions between word and image were common, not only in prints of

Saigõ s demise, but in prints of the Satsuma Rebellion in general. A print by

5Because the dates on many nishikie include the month but not the day, it is impossible to create a

definitive chronology of seppuku prints.

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigô Takamori 701

Matsuyama from March 8, 1877 (Kagoshima sexto no zu, printed in Tokyo), for

example, shows Saigô, but his face is obscured by an exploding red sphere, pre-

sumably an artillery shell. The cartouche, however, describes how the Imperial

Army broke the siege of Kumamoto Castle, and makes no mention of Saigõ at

all, much less a severe and disfiguring injury. The cartouche confesses that,

while details of the battle are hard to come by (hõ voa shirigatashi to iedomo),

it is certain that government forces won a resounding victory. Saigô s obliteration

by a shell thus represents the government s victory, not the details of the battle.

In this way, nishikie images were thematically related to prose accounts, but were

intended as evocations of social meaning rather than transparent representations

of material details.

After this brief explosion of fantastic images, tales of Saigô s seppuku all but

vanished. In the 1880s, for example, most biographies of Saigõ avoided discussion

not only his death, but of the entire Satsuma Rebellion. Saigõ was remembered,

in this period, for his contributions to the Meiji state, rather than for his rebellion

against it. Beginning in the 1890s, however, biographers and historians began to

embellish accounts of Saigõ s death, and by the early 1900s, accounts of Saigô s

suicide had become a fixture of biographies and textbooks. These biographies,

however, claimed to describe the material conditions of Saigõ s death, and there-

fore could not contain large internal contradictions. We thus find an increasing

emphasis on Saigõ s determination, loyalty, and calm demeanor - affective qual-

ities that cannot be disproven through material evidence.

Further, these biographies of Saigõ were produced under different ideologi-

cal conditions. The nishikie of 1877 sought to represent a momentous contem-

porary change: the consolidation of the Meiji state and the disappearance of

the samurai class as a coherent political force. By the early 1900s, however, the

disappearance of the samurai class was already a historical phenomenon, and bio-

graphers sought to embed Saigõ and the samurai into a new national narrative.

Central to this reinterpretation of Saigõ was the invention of modern bushidõ

and its emergence as a national ideology. The idea that samurai practices consti-

tuted Japans national heritage, rather than a feudal impediment to progress,

prompted a réévaluation of Saigõ s life and death.

The Rediscovery of Bushidõ

Bushidõ as a national ideology emerged in the 1890s and represented a strik-

ing reversal of earlier government policy. The formation of the conscript army in

the 1870s was an explicit rejection of the idea of a warrior elite, which was

derided as inimical to the ideal of equal service to the emperor. In the November

28, 1872, Dajõkan proclamation explaining conscription, samurai were

denounced as hereditary idlers (sesshü zashoku), while conscription was cele-

brated as part of "restoring the balance between high and low, and granting

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

702 MarkJ, Ravina

equal rights (jinken) to all" (Yui, Fujiwara, and Yoshida 1989, 67-68). The devel-

opment of bushidõ reversed this attitude toward samurai tradition. Traditional

warrior virtue became part of the common cultural heritage of all Japanese sub-

jects. With the samurai estate safely dead, select aspects of warrior culture could

be recast as Japans common cultural heritage. Notably, bushidõ became a

national tradition only a generation after samurai had lost their hereditary

powers and privileges. So striking was this new appraisal of samurai tradition

that in 1912, Basil Hall Chamberlain dismissed bushidõ, and much of the

modern emperor system, as "inventions/*6

Bushidõ was a fairly obscure term before the 1890s, but surged in popularity

after 1905. The National Diet Library's Modern Digital Library (Kindai dijitaru

raiburarii) allows for a simple but objective measure of the term s usage: the

database indexes Meiji-era texts by title, author, publisher, and table of contents

(see table 1). The database produced no hits for the term bushidõ prior to 1893,

and during the 1890s, citations for bushidõ appeared roughly once a year. This

rate increased tenfold after 1901 to nearly ten titles per year, and to more than

fifteen titles between 1906 and 1910. This growth in citations was attributable,

in part, to general growth in the publishing industry and to increased interest

in military affairs during the Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese wars. But

while hits for terms such as "military" (gunji) also increased, the bushidõ boom

was without parallel.

Modern bushidõ ideology had several major sources. It was a product largely

of what Carol Gluck has termed minkan ideologues: "journalists, intellectuals,

and public figures who produced a disproportionate amount of 'public opinion*

(yoron) of the period" (1985, 10). Many minkan ideologues held government

positions, and their views enjoyed increased currency because of those positions,

but they were not simply state ideologues. A prime example is Inoue Tetsujirõ, a

professor of philosophy at Tokyo Imperial University. Intensely prolific, Inoue

was central to the creation of Meiji state ideology, particularly through his 1891

commentary on the Imperial Rescript on Education. In that commentary, of

which some 4 million copies were eventually printed, Inoue "fabricated the rudi-

ments of the family-state ideology," giving a modern, quasi-utilitarian gloss to

the morals of loyalty and filial piety (Gluck 1985, 128-30; Pyle 1969, 127-28).

Because Inoue s commentary was written at the explicit request of the Ministry

of Education, his views had quasi-official status. Some of his interpretations,

however, were at odds with those of the authors of the rescript. Most striking

was Inoue s assertion that the rescript constituted a state religion for modern

Japan. This was in direct conflict with the thinking of one of the rescripts

prime architects, Motoda Eifu, who had hoped to define the rescript as a

"national teaching," independent of any religion. The prime authors of the

6On Chamberlains essay and current interest in the "invention of tradition," see Kevin M. Doak

(1999), John S. Brownlee (1998-99), and Henry D. Smith (2006).

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigô Takamori 703

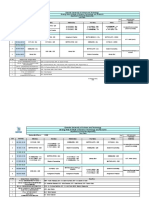

Table 1. Citations of bushido and related terms.

Bushidõ Gunji (military) Senso (war)

1891-1895 4 81 286

1896-1900 5 65 137

1901-1905 47 155 334

1906-1910 85 122 262

1911-1915 68 122 114

Compiled June 2, 2008, at

Meiji constitution, I

separation of church

vided an opportunity

sidered dangerously

state was not univoc

official status.

Inoue was one of the earliest and most active proponents of bushidõ as a

national ideology, and his views were especially influential because of his promi-

nence in academic and government circles. In the early 1900s, Inoue began to

emphasize the importance of bushidõ as a distinctly Japanese philosophy. In a

1901 lecture to the teachers at a Japanese military academy (Rikugun chuõ

yõnen gakkõ), Inoue argued that bushidõ was "central to the spirit of the

Japanese people" and a sui generis spiritual system. It "developed together

with the martial spirit of the Japanese people" and the Japanese people them-

selves "originated together with that spirit." Although military in origin,

bushidõ was not primarily about violence. Rather, it was a moral code that

emphasized both self-cultivation and self-sacrifice, appropriate to many

modern situations (Inoue 1901, 2-3, 8, 46-65).

In a series of publications in the early 1900s, Inoue developed an influential

genealogy of bushidõ. Although the tradition was rooted in the practical experi-

ence of generations of warriors, the progenitor of bushidõ as a written body of

knowledge was Yamaga Sokõ (1622-85), and Sokõs thought was at the root of

the brave self-sacrifice of the forty-seven Akõ rõnin, immortalized in the play

Chüshingura. In the bakumatsu era, according to Inoue, bushidõ ideology was

further honed by Yoshida Shõin (1830-59), who was, according to Inoue, a dis-

ciple of Yamaga (Inoue 1901, 30-31). Inoue s genealogy ofbushidõ was extremely

influential and reproduced in numerous texts on history, literature, and philos-

ophy, as well as government tracts on national ethics. The famous 1937 govern-

ment pamphlet Kokutai no Hongi (Cardinal Principles of Our National Polity),

for example, reproduced Inoues emphasis on Yamaga and Yoshida. Inoues

status as a quasi-official spokesman for Japan s martial spirit was further cemen-

ted in 1941 when War Minister Tojo Hideki provided a calligraphic epigram for

Inoues Instruction for Warfare (Senjinkun) (Tucker 2002).

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

704 Mark J. Ravina

Inoue was unparalleled in the vehemence with which he promoted bushidõ

as a national ideology, but other state-affiliated intellectuals were active as well.

The prominent historian Shigeno Yasutsugu, for example, coauthored a 1909

volume that traced the origins of the doctrine from the dawn of time to the

present (Shigeno and Kusaka 1909). Shigeno, widely considered one of the foun-

ders of modern historical writing in Japan, developed a close association with the

Meiji state in 1881 when he was appointed deputy editor oí Dai Nippon kennen

shi (Chronological History of Japan), an official state-sponsored history covering

1392 to 1867 (Ketelaar 1990, 191-94; Numata 1961; Tao 1997).

In his historical writings, Shigeno was deeply committed to historicizing

Japans ancient chronicles. For Shigeno, the creation of Japan by the gods

Izanagi and Izanami marked the beginning of historical time in Japan, and

national history needed to be measured and explained through the genealogy

of the imperial line. In their study of bushidõ, Shigeno and his coauthor,

Kusaka Hiroshi, similarly linked the origins of bushidõ to Japanese creation

myths. "If we are to trace the distant beginnings of our country's bushidõ"

they wrote, "we find that its origins were already present in the age of the

gods, occurring together with the founding of the country, when the two gods

Izanagi and Izanami created Õyashima [Japan] with their jeweled spear, when

Amaterasu bequeathed the country with a precious sword [Kusanagi], thus

adding it to the three sacred regalia." Thus, according to Shigeno and Kusaka,

the origins of bushidõ antedated the emergence of samurai warriors by some

1,500 years. Therefore, it was not a warrior code but a timeless national ideology,

"something that the people (kokumin) should not forget even for an instant"

(Shigeno and Kusaka 1909, 1, 424).

What is remarkable about the sudden explosion of bushidõ studies is how pol-

itical rivals contested the meaning of bushidõ, but not its importance as a

uniquely Japanese corpus of thought. Japanese Christians, for example,

embraced bushidõ and used their support for bushidõ to refute accusations of

disloyalty to the throne. Thus, although Inoue argued publicly that Japanese

Christians could not be loyal subjects, one of the most widely read books on

bushidõ was Bushido: Soul of Japan, written by Nitobe Inazo, a Christian

convert. Nitobe treated bushidõ as analogous to European chivalry and, intrigu-

ingly, saw seppuku as analogous to Roman stoicism and Christian martyrdom

(Nitobe [1900] 1905, 122-23). Indeed, Nitobe argued that bushidõ had

allowed Japan to attain a Christian level of civilization in the absence of Christian-

ity. The samurai, Nitobe claimed, were cultured men of arts and letters and their

appreciation of the arts restrained them from brutality even in combat (49).

Further, a samurai s sense of duty was comparable to the Christian doctrine of

service, "the sacred key-note of His [Christs] mission" (147). Indeed, the paral-

lels between Christianity and bushidõ were so strong as to "confirm the moral

identity of the human species" (125). Nitobe s Bushido was key in shaping

Western perceptions of Japan, and became influential in Japan as well, running

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigõ Takamori 705

through eight Japanese editions before 1905 (Yorimitsu 2007). Inoue felt com-

pelled in his 1901 lecture on bushidõ to refute the parallels between chivalry

and bushidõ (Inoue 1901, 8-9).

The ubiquity of bushidõ reflected the plasticity of the concept. The noted

liberal activist Õzaki Yukio, for example, argued that bushidõ was important

primarily for Japanese commerce. In an 1893 treatise on political reform,

Õzaki argued that bushidõ was essential, but not for military reasons. Echoing

Samuel Smiles and Horatio Alger, Õzaki claimed that successful men pursued

not fleeting profit but respectable prosperity. English businessmen were success-

ful, Õzaki argued, because they were gentleman, and therefore were reliable,

trustworthy, and temperate. Because bushidõ emphasized loyalty, trustworthi-

ness, and restraint, it was essential to the success of the Japanese economy.

Bushidõ would save Japanese businessmen from rank materialism and guide

them toward lasting honor and prosperity (Õzaki 1893, 25-28).

For most commentators, however, bushidõ was a martial doctrine. Central to

the rise of modern bushidõ were Japan s victories in the Sino-Japanese War

(1894-95) and the Russo-Japanese War (1904-5). Both events focused attention

on the military as an emblem of Japanese national pride and accomplishment.

Japan s success in modern warfare sparked, ironically, a revival of traditional

martial arts techniques and prompted the founding in 1895 of the Greater

Japan Martial Virtue Society (Dai Nihon Butokukai). The society was devoted

to the revival of traditional swordsmanship and archery, but also the cultivation

of a traditional warrior ethos. Fencing, they claimed, was the quintessence of

the Japanese spirit, and it led to the cultivation of the mind, body, and soul

(Ozeki 1910, 1). The groups early marital arts expositions were observed by

the emperor, giving it a state imprimatur, and it later received indirect support

from the army, the police, and the Home Ministry. Local chapters of martial

arts societies linked bushidõ to patriotism, arguing that "the great principles of

loyalty and patriotism are special characteristic of martial virtue" (Ozeki 1910, 5).

The Japanese military grew interested in bushidõ in the aftermath of the

Russo-Japanese War. Japanese military strategists concluded that Japan had

defeated Russia because Japanese "fighting spirit could make up for, if not

replace, shortages of manpower and some deficiencies in advanced armament."

This belief stemmed, in part, from distorted reports of battlefield events, but it

led nonetheless to an emphasis on "motivating the rank and file to fight to the

point of exhaustion and to sacrifice their lives" (Kowner 2007, 34). Based on

this perception that Japan s victory had come from its spiritual ascendancy, the

army became concerned with "the moral quality of the soldier and of the

people from whom they came." Urbanization meant that new recruits came

increasingly from "morally suspect urban areas," and the expansion of national

primary education meant that conscripts were better educated and thus less malle-

able. In order to meet these challenges, the army had to become "the school of the

people" and shape the character of the Japanese populace. This goal required new

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

706 Mark J. Ravina

institutions, such as the Imperial Military Reserve Association (Teikoku zaigo gun-

jinkai), an organization designed to foster patriotism and martial valor, with local

branches down to the village level (Humphreys 1995, 12-16). Bushidõ was

central to this new project. In 1911, for example, General Tanaka Giichi, future

army minister, prime minister, and a major architect of the reserve association,

declared that "the roots of the spirit of Japan and of bushidõ lie deep within the

Japanese people." Tanaka proposed using the reservists organization to spread

the spirit of bushidõ and combat national moral decay (Smethurst 1971, 823).

Perhaps the most striking public example of the new veneration of bushidõ

was the 1912 suicide (junshi) of General Nogi Maresuke, hero of the Russo-

Japanese War. According to his last note, he sought both to follow his lord, the

Meiji emperor, into death and to atone for losing his regimental banner during

the War of the Southwest. Although some observers considered Nogi s junshi

bizarre and retrograde, it was a dramatic example of how Japanese military offi-

cers were rethinking bushidõ as an emblem of Japanese culture, rather than an

embarrassing vestige of a feudal past (Gluck 1985, 221-25).

This new emphasis on bushidõ can be understood in the broader context of

social management after the Russo-Japanese War. The war was enormously

expensive and, unlike the Sino-Japanese War, the economic costs were not

defrayed by an indemnity. Thus, as Sheldon Garon has observed, "postwar man-

agement quickly assumed the form of social management, as officials strove to per-

suade the public to bear the new burdens of the nation s great power status/'

Public campaigns to raise Japan s international competitiveness were described

as preparation for "peacetime economic war" - a conflict requiring diligence,

frugality, discipline, and self-sacrifice. These goals dovetailed with many of the

tenets of modern bushidõ: selfless service, self-restraint, and loyalty. These cam-

paigns were supported by a range of groups, including the national bureaucracy,

public intellectuals, local government, and civic groups. The Hõtokusha, for

example, were private mutual aid societies dedicated to the principles of Ninomiya

Sontoku, but they were, in theory, coordinated by a central agency created by the

Home Ministry. The Home Ministry also relied on Christian relief groups, despite

official suspicions about the loyalties of Japanese Christians (Garon 1997, 9, 13,

46-47). In a parallel fashion, a wide range of civic organizations and individuals

(including ideologically suspect Christians) worked with government agencies to

promote bushidõ as a national ideology. Indeed, it was this diversity of advocates,

ranging from martial arts masters to Christian educators and from Diet members

to army officers, that secured the ubiquity of bushidõ in popular discourse.

Bushidõ and Biographies of Saigõ

Saigõs posthumous pardon in 1889 removed any concern that praise for

Saigõ might be seen as disloyal. But until the rise of bushidõ, few author

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigõ Takamori 707

chose to focus on the details of Saigo s death. In an account published in Novem-

ber 1877, for example, Ogamino Naka detailed the last days of the rebel army and

their march into a hail of Imperial Army gunfire and artillery. They died, he

wrote, heroically, their spirits ascending to heaven like gun smoke. Skipping

any details of Saigõs exact death, he then moved to an evaluation of Saigõs

life, reporting that Saigõ, despite his opposition to the government, was a great

man, unrivaled in his courage, ingenuity, and popularity. "There has never

been and will never be/' he concluded, "another Saigõ" (Ogamino 1877).

Eliding the specifics of Saigõ s death was a fairly common practice. A biography

of Saigõ by Yasuda Naotaka, for example, made no mention of Saigõ s death, but

reproduced a letter in which he exhorted his followers to die with honor (Yasuda

1889, 28-31).

Some biographers saw fit to skip not only the details of Saigõ s death, but the

entire War of the Southwest. In a detailed three-volume biography of Saigõ pub-

lished from 1899 to 1903, for example, authors Murai Gensai and Fukura Chiku-

tei concluded their story in 1874, with Saigõs return to Kagoshima and his

involvement in the shigakkõ network of samurai academies. Rather than praise

Saigõs death, biographers focused on his achievements. In a collection of biogra-

phies on the theme of risshin (personal advancement), for example, Saigõ was

celebrated for his rise from humble origins to national prominence and

success, including his receipt of a 2,000 koku award for loyal service in the Res-

toration (Shinoda 1892, 13-15).7

In the mid-1890s, however, authors began to experiment with various means

of giving Saigõ a more bushidõ-like death. A seminal example was an 1894 bio-

graphy by Katsuta Magoya. According to Katsuta, Saigõ and his men marched

resolutely into a hail of gunfire. Saigõ was hit by a stray bullet, collapsed, and

ordered Beppu to take his head. Beppu, seeing no alternative, cut off Saigõ s

head, put it in a felt bag, and buried it at the roadside. He then announced

that Saigõ was dead and that the end was at hand. Thirty-nine of Saigõ s men,

including Murata, Ikegami, Beppu, and Henmi, then stabbed themselves to

death (jijin). Katsutas account gave Saigõ volition in his own death: he asked

Beppu to cut off his head (Katsuta 1894, 8:148-49). Katsutas work was, for its

time, remarkably well documented, and, according to his citations, he based

his account of Saigõs death on several published sources. Nonetheless, it

seems clear that Saigõ s request to Beppu was Katsutas invention: none of Kat-

sutas sources mention Saigõ asking Beppu to take his head. According to Teichü

vangai, a history published by Kagoshima prefecture in 1879, "a bullet passed

through Takamori s thigh and he could not move, so Beppu Shinsuke quickly

cut off his head, put it in a felt bag, and buried it" (Kagoshima-ken 1879,

2:28). Seinan seitõshi, published by the Japanese navy in 1885, gives a similar

'On the topic of risshin, see Earl H. Kinmonth (1981).

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

708 Mark J. Ravina

account: "Saigõ suffered a bullet wound and Beppu, realizing that Saigõ would

never fight again, cut off his head and secretly buried it" (Kaigunshõ 1885,

4:46). Seinan senkt reports that a lieutenant Yasumura in the Imperial Army

was closing in on Saigõ, so Beppu attacked Yasumura and then "rushed to

Saigõ, cut off his head and ran off with it" (Kosuge 1897, 99). Senpõ nikki, the

wartime journal of a Kagoshima partisan, reports only that on the evening of

September 24, "we received a report that Master Saigõ, Kirino, Murata, and

the others had died in battle on Shiroyama and that the fighting was completely

over" (Sassa [1891] 1986, 199).

Katsutas intervention was a creative solution to the inelegance of Saigõ s

death. It gave Saigõ volition in his own demise without openly contradicting

any of Katsutas sources. Katsuta did not have Saigõ sit, or even move, so his

description is consistent with a bullet penetrating and shattering Saigõ s femur.

But Katsuta made Saigõ an agent in his own demise, and although his account

was still far from even a loose definition of seppuku, it was consonant with

broader notions of an honorable death. Accordingly, Katsutas depiction of

Saigõ s last moments was picked up by authors such as Kakuroku Yashi (1900,

100-101; 1909, 100-101) and Yamaji Aizan (1915, 57-58), and it became a

fairly standard account of Saigõ s death.

At the same time, other sources began describing Saigõ s death as suicide,

without particular explanation. This trend was particularly striking in school-

books. A 1902 school textbook by Fujioka Sakutarõ, for example, linked Saigõ

to obstinate opponents of progress, but claimed that he committed suicide

(jisatsu) at Shiroyama (Fujioka 1902, 2:142-44). A textbook by Honda Asajirõ

from the same year took this further and noted that Saigõ and his followers

stabbed themselves to death (jijin) (Honda 1902, 2:200). In 1903, the Japanese

government changed its policy of approving textbooks from private publishers to

a more restrictive system of official textbooks issued by the Ministry of Education

(Monbushõ). The first elementary school history text issued under the new

policy, Jinjõ shõgaku Nihonshi (1909), described Saigõ s death as suicide

(jisatsu), and thus gave official government approval to this new account of

Saigõs demise (Kaigo 1961-67, 19:551, 609).

The earliest detailed account of a seppuku scene I have found is a 1909

excerpt from Shiroyama rõjõ chõsa hikki, notes for a history of the siege of Shir-

oyama by Kajiki Tsuneki. A veteran of the War of the Southwest, Kajiki spent a

year in prison after his capture by government troops in 1877. An ardent nation-

alist, he traveled to Korea in 1882, hoping to join up with other Japanese forces in

a violent struggle at the Korean court, the Imo mutiny. Arriving too late, he

returned to Japan and joined the Fukuoka police force. Around 1902, Kajiki

became active in the Kokuryûkai, a militant nationalist group. Founded in

1901 by Uchida Ryõhei, the Kokuryükai was committed to the military subjuga-

tion of China and Korea, and its members saw in Saigõ s fragmentary comments

on Korea a precedent for their own beliefs. Kajiki began working on the

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigö Takamori 709

Kokuryükais history of the War of the Southwest, Seinan kiden (1908-11), which

included a snippet of Kajiki s work in progress. According to that excerpt, Saigõ

was shot through the hip, called Beppu to his side, and then sat upright and faced

east toward the Imperial Palace while waiting for Beppu to take his head (Kokur-

yûkai 1908-1911, vol. 2, pt. 2, 702-3; Kajiki 1912, appendix 1-3).

When Kajiki published his own history of the war three years later (Satsunan

ketsurui shi), the seppuku was still more involved and dramatic. Saigõ and his

men assembled in front of their cave on Shiroyama and marched out proudly

into a hail of gunfire. Noticing the rapid approach of the enemy, Henmi asked

Saigõ, "Is this a good place?" meaning, should the group kill themselves on the

spot? Saigõ responded, "not yet," meaning that they needed to advance further

and compose themselves. As they advanced, their number shrank, some killed

in enemy fire, some falling on their own swords. Finally, Saigõ was hit by a

gunshot, from the shoulder through the breast. He calmly called for Beppu,

announcing that this was indeed the right time and place. He then sat upright,

tucked his knees under his torso (kiza), solemnly adjusted his collar, looked

east, and paid his last respects to the emperor. Beppu, himself badly injured,

came to Saigõ s side, begged his forgiveness, and cut off his head (Kajiki 1912,

833-35).

Kajiki s account is remarkable for its bold revisionism. In order to have Saigõ

sit upright with composure and bow toward the Imperial Palace, Kajiki changed

the nature of Saigõ s injuries. Instead of the hip, Saigõ was now shot through the

shoulder. This made Saigõ s seppuku scene more plausible, but it contradicted

published accounts familiar to Kajiki from his work on Seinan kiden. Indeed, it

also contradicted the research notes that Kajiki had published only three years

earlier. But these empirical problems were overshadowed by outside events. Sat-

sunan ketsurui shi was published one month after General Nogi Maresuke com-

mitted suicide. Because Nogi had fought against Saigõ thirty-five years earlier,

the parallels could not have been stronger: two great Japanese martial heroes, for-

merly enemies, were now united in death through their devotion to the emperor

and their dedication to the spirit of bushidõ. This was nationalist bushidõ at its

most effective, and it generated enough interest in Kajiki s history to warrant a

second printing later that year.

In subsequent years, Kajikis narrative became a fairly standard account of

Saigõ s death. A version of Kajiki s account appeared in 1926 in the biographical

section of Dai Saigõ zenshü, a three-volume collection of Saigõ s letters. As in

Kajiki s version, Saigõ strode into enemy fire, looking for the right spot to die.

Shot in the thigh and abdomen, he sat upright (tanza) and bowed to the Imperial

Palace before Beppu took his head. This version changed Kajikis dialogue

slightly: rather than seeking a composed (shõyõ) death, for example, Saigö

sought a magnificent (rippa) death. It also changed Saigõs injuries, deleting

the shoulder, restoring the thigh, and adding the abdomen. These differences

aside, the account clearly derived from Kajiki (Dai Saigõ zenshü henshü iinkai

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

710 Mark J. Ravina

1926, 3:1026-27). A 1927 biography of Saigõ, published to commemorate the fif-

tieth anniversary of the founding of Saigõ Shrine, reproduced, without attribu-

tion, several key details of Kajikis version, including much of the dialogue

between Saigõ and his followers, and his bow to the Imperial Palace (Nanshü

jinja gojünen-sai hõsankai 1927, 455-57). Virtually the same account appeared

in 1938 as part of a popular biography series entitled Jinbutsu saikentõ sõsho

(Õhara 1938, 331-32) and in a one-volume biography by the prolific novelist

and essayist Mushanokõji Saneatsu (1938, 455-57).8

Mushanokõji s biography of Saigõ warrants special attention because it high-

lights the connection between Saigõ s seppuku and Japanese militarism. Musha-

nokõji began his literary career as a Tolstoian idealist and pacifist, and he was a

key member of the Shirakaba (White Birch) literary magazine. In 1912, he dis-

missed the ritual suicide of General Nogi as an embarrassing anachronism:

"General Nogi s death can be adored only by those with unhealthy reason . . .

Unfortunately, there is nothing in the death of Nogi which appeals to humanity,

whereas the death of Van Gogh is a loss to humanity" (Arima 1969, 107-8). In the

1930s, however, he began to support Japanese militarism, influenced perhaps by

his elder brother, who was Japan s ambassador to Nazi Germany. By the 1940s,

Mushanokõji was an outspoken proponent of the war effort, and as late as

November 1944, he was writing of coming victory against the United States

(Keene 1964, 212). After the war, he was purged by the U.S. occupation for

his strident support of the war effort. Mushanokõji s biography of Saigõ falls at

the beginning of his passage from idealistic pacifism to an enthusiastic

embrace of militarism.

Mushanokõji s biography is also important for its impact on American writing.

Although his work on Saigõ was a minor part of his massive oeuvre, it was trans-

lated into English in 1942 by Moriaki Sakamoto under the title Great Saigo. Saka-

moto lovingly detailed the legend of Saigõs seppuku for English-language

readers. Striding into gunfire, Saigõ urged Beppu and Henmi forward: "No, let

us go farther up to the main road, where we shall die glorious deaths." After pro-

ceeding further, Saigõ was shot in the thigh and abdomen, asked Beppu to

prepare to take his head, "calmly squatted down, and turning towards the east,

worshipped the Imperial Palace." As Beppu moved "with consummate skill" to

take his masters head, "Saigo was equanimity itself (Mushakoji 1942, 479-

80). Sakamoto s translation was, until 1987, the only English-language biography

of Saigõ, and it had a definitive impact on American writing. In his influential

Nobility of Failure (1975), Ivan Morris relied heavily on Sakamoto, thus bringing

Kajiki s story to generations of college students and general readers. The more

recent Columbia Encyclopedia (2000) still cites Sakamoto as its reference for

8In English, Mushanokõji s name is sometimes rendered as Mushakoji. For a consideration of his

life and work, see Donald Keene (1964), William F. Sibley (1979, 29), and Arima (1969).

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigõ Takamori 711

Saigõ. These works helped inscribe Saigõs suicide into American discourse as

history.

Saigõ thus committed "suicide" only decades after his death. Although some

nishikie described Saigõ s death as seppuku in 1877, the story did not appear in

more respectable print media until some two decades later. After 1894, however,

biographies of Saigõ gave him increasing agency in his own death. At first he

merely asked Beppu to take his head, but after 1912, it became increasingly

common for Saigõ to carefully choose the place of his death and calmly show

his respect to the emperor before having Beppu end his life. Through widespread

dissemination and reproduction, these accounts of Saigõ s death became refer-

ence work facts.

It is worth noting that although the Ministry of Education s 1909 textbook

described Saigõ s death as a suicide, the government published contradictory ver-

sions of Saigõ s death. The 1920 revision of the textbook (and subsequent 1934

revision) reported that Saigõ died in battle (senshi) (Kaigo 1961-67, 19:608,

20:103-4). Textbooks after 1940 elided Saigõs death, mentioning that he was

defeated and focusing instead on the emperors concern for civil order (Kaigo

1961-67, 20:214, 349). Clearly the government remained ambivalent about

turning a rebel into a hero. Indeed, in order to celebrate Saigõ as a Japanese

hero, textbooks needed to downplay his role as a rebel against the imperial gov-

ernment. The 1909 text, for example, reported that in 1874 Saigõ "retuned home

to Kagoshima and opened a private academy to nurture [local] children. Among

them were many who were unhappy with government policy and, in February

1877, they turned to Saigõ as their leader (Saigõ o yõshite) and raised an

army." Saigõ accepted command of this army, but the initial rebellion was

launched by his reckless followers. In general, the Ministry of Education

remained skittish about glorifying rebels. The text of Kokutai no hongi, for

example, followed Inoue Tetsujirõs overall interpretation of bushidõ, but

omitted his valorization of the forty-seven Akõ rõnin. Those men had attacked

an officer of the national government, and, whatever their courage, insubordina-

tion was not something the Ministry of Education was prepared to endorse.

Lost Legends and Counternarratives

The most glorious legends of Saigõ s suicide were developed by the Japanese

right, which sought to fit Saigõ into an extended narrative of the Japanese mili-

tary. The state, with inconsistency and trepidation, accepted Saigõs suicide as

part of remaking Saigõ as a national hero. But this redaction of Saigõ lore

required the exclusion of Saigõ legends that might challenge the Meiji state. In

order for the Meiji state and its defenders to venerate Saigõ, he needed to be

noble, but dead; his vitality, whether metaphorical or real, was a challenge to

the political establishment. The reproduction of Saigõ as a national hero thus

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

712 Mark J, Ravina

required that some legends be relegated to fantasy while others be redeployed as

history.

One outcome of this process was the loss of Saigõ as a proponent of radical

change. In 1877, tabloids represented this aspect of Saigõ s persona by giving him

a flag with the phrase shinsei kõtoku, "A New Government, Rich in Virtue." This

slogan combined both a desire for revolutionary transformation - "a new

government" - and a desire to maintain the paternalism of the early modern

order - "rich in virtue." The slogan harkened back to the notion that the state

should be benevolent rather than bureaucratic. Implicit in the phrase was the

contradictory but compelling desire for the vitality of a free society combined

with the security of Confucian paternalism. The banner appeared in scores of

nishikie, and was fairly standard in depictions of battle scenes by the summer

of 1877. It is unclear whether Saigõ actually flew such a standard. The nishikie

tradition stemmed from a single mention of such a banner, based on hearsay,

in the Yübin hõchi shimbun on March 3, 1877 (Sasaki 1994, 331). There are

no eyewitness accounts of such a flag, nor any surviving examples. In the nishikie

tradition, however, shinsei kõtoku was the official manifesto of the rebel cause.9

The image of shinsei kõtoku was popular because it captured the dualistic

appeal of Saigõ s cause. When Edward Morse wrote that Saigõ was "beloved by all

Japanese," he was not too far off the mark (Morse 1917, 1:269). Saigõ, in 1877,

represented both the virtues of the traditional order and the possibility of revolu-

tionary transformation. This duality generated widespread sympathy. In Kuma-

moto, for example, the countryside erupted in rebellion as thousands of

peasants voiced their grievances against the Meiji government. The commoners

were suspicious of the new land tax and angry over new local levies designed to

pay for national mandates, such as public education and land surveys. Across the

prefecture, they both petitioned and physically attacked local officials, demand-

ing delays in the new land tax and reductions in levies. In Katamata village, vio-

lence erupted when one Fujii Ihei returned from Kumamoto City on February

25 and reported the arrival of Satsuma troops. If the rebels came to Katamata,

he declared, villagers would not have to pay taxes and would be able to choose

their own village officials. Local officials managed to contain the situation for a

week, but by early March, they were confronted by death threats and fled the

village (Kumamoto junsatsuchõ 1877). Order was not restored until the rebel

army was driven from Kumamoto in the fall.10

9I base my reservations about Saigõ s battle flag in part on conversations in 2001 with Yamada Shõji,

curator of the Saiga nanshü kenshõkan, a museum devoted to Saigõ artifacts and memorabilia.

Yamada observed that over several decades of collecting artifacts from the War of the Southwest,

including calligraphy, guns, swords, and flags, he had never seen anything resembling the shinsei

kõtoku flag. Had he heard of such a banner, he insisted, he would have bought it at once.

1()The incident is also discussed in Mizuno Masatoshi (1978, 234; 2000, 73-76). For the Kumamoto

rebellions in general, see Mizuno (2000, esp. 69-149, 226-78).

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigò Takamori 713

The rebels also drew support from a range of disaffected samurai groups. In

Fukuoka and Nakatsu, for example, there were sympathetic uprisings by tra-

ditionally minded samurai. But the rebels were also supported by groups such

as the Kyõdõtai, a Kumamoto samurai brigade formed by members of the

Ueki gakkõ, a radical school in Ueki town. The core curriculum at the Ueki

gakkõ included translations of Rousseau s Social Contract, Mills On Liberty,

and Montesquieu's The Sprit of Laws, and the schools founder, Miyazaki

Hachirõ, was an important participant in Itagaki Taisukes campaign for an

elected national assembly (Shindõ 1982, 25-26). n In Kõchi, police arrested a

group of former samurai as they collected guns and ammunition. Under interrog-

ation, the leader complained that the government was arrogating political power,

"plunging the people into misery, and recklessly oppressing the people s rights

(minken), and bringing the Japanese empire to the brink of ruin" (Kagoshima-ken

ishin shiryõ hensanjo 1978-80, 1:672).

Saigõ s appeal as a progressive was also reflected in period newspapers. The

Osaka nippõ, for example, was an outspoken advocate of representative govern-

ment and ran afoul of censorship laws in 1876 for asserting that "the government

is a government of the people (jinmin), not a government of the monarch

(kunshu)" (Inoue 1966, 436-37). Reporting Saigõ s death on September 25,

1877, the newspaper again pushed the bounds of censorship and celebrated

his accomplishments, comparing him to a range of world heroes: Kusunoki Masa-

shige, the Qin general Ding Yu, and Napoleon Bonaparte. By contrast, conserva-

tive newspapers dismissed Saigõ as a reactionary. The Yübin hõchi shinbun, for

example, lambasted Saigõ for his dictatorial ambitions and military incompe-

tence. Saigõ wanted to turn back the clock and reverse the progress of the

Meiji era: "Saigõ s last battle was not just the end of Saigõ, but a battle announ-

cing the end of feudal power (hõken seiryoku)" (September 25, 1877). This cri-

tique reflected the newspapers role as a quasi-governmental organ: the Yübin

hõchi shinbun had been founded in 1872 by Maejima Hisoka, the official who

pioneered Japan s modern postal system.

Saigõ also received the support of leading intellectuals such as Fukuzawa

Yukichi, who wrote a lengthy essay in his defense in late 1877 (Fukuzawa

2002, 9:31-74, 301-7). 12 Fukuzawa rejected the idea that Saigõ was a reactionary

who would restore feudal society. On the contrary, he argued, Saigõ had been

instrumental in the dissolution of the domains. While some of Saigõ s followers

had reactionary notions, "Saigõ certainly did not despise freedom and progress,

[but] was, in reality, a follower of the spirit of civilization (bunmei no seishin)yy

(9:44). While Fukuzawa lamented Saigõs use of force, he was equally critical

1 !Saigo specifically mentioned his use of the Kyõdõtai as spies in a March 12 letter to Oyama Tsu-

nayoshi (STZ 3:538). On Kumamoto during the War of the Southwest, see Steven Vlastos (1989,

399-401), Tamamuro Taijõ (1966, 138-40), and James H. Buck (1959, 175-76).

12Fearing censorship or retaliation, Fukuzawa did not publish the essay until 1901.

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50an 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

714 Mark J. Ravina

of the autocracy of the Meiji government, which, he argued, had invited Saigõ s

rebellion through its repressive policies. ''We should feel compassion for Saigõ,

for it was the government that drove him to his death" (9:72). In a brief draft

manuscript written during the war, Fukuzawa was still bolder: "if the Satsuma

forces win, they will certainly establish a new government and grant the

people rights." But such a government would founder because men like Saigõ,

with their lack of concern for administrative detail, would be deceived by the

existing bureaucracy. Thus, Fukuzawa concluded, while the war was a huge

setback for Japan, there was no reason to favor one side over the other (9:78).

This vision of Saigõ as a revolutionary inspired the legend that he did not die in

battle, but had fled Japan and was waiting to return. Such stories began to circulate

in the summer of 1877, as the rebel army retreated through the mountains and

dense forests of Kyushu. Saigõ disappeared from public view, generating fantastic

rumors. On August 4, for example, the Yomiuiri shinbun reported rumors that

Saigõ had fled to China or to Korea, and that the government was offering a

reward of 150 yen for news of his whereabouts. The story continued after Saigõ s

death, and rumors that he was hiding in China appeared in the Kinji hyõron and

the Niigata shinbun. On July 13, 1878, the Chõya shinbun reported that an

amazing number of people believed that Saigõ was still alive. Three years later,

the Yübin hõchi shinbun reported widespread belief in a rumor that Saigõ was

hiding on an island in India, and that he was going to return to Japan to set things

right. This story was spread by street peddlers selling pamphlets (Ikai 1992, 5-6).

These rumors dissipated in the late 1880s, but they returned with unexpected

vibrancy in the spring of 1891. The occasion was the planned visit to Japan of

Russian Crown Prince Nikolai, and the legend was now revised so as to place

Saigõ in Russia. The story, as reported on March 31 in the illustrated tabloid

Nihon, ran as follows: Saigõ and his key lieutenants (Kirino Toshiaki, Murata

Shinpachi, etc.) had fled to Koshiki Island on the eve of the Battle of Shiroyama.

There, they had been picked up by a Russian warship and taken to Siberia, where

they then helped train Russian troops. During his trip to Russia in 1884-85,

Kuroda Kiyotaka (prime minister, 1888-89) had visited Saigõ and the two had

discussed the future of Japan. Saigõ had promised to return in 1891, after the

establishment of a national assembly, and the Russian crown prince had agreed

to accompany him back. The details of this rumor reveal the complexities of

Saigõ s public persona as both a samurai and a progressive leader: Saigõ was in

Russia training troops, but was to return to Japan after the opening of the

Diet. The legend was picked up by other newspapers and became the basis for

a nishikie published on April 8 (Sasaki 1994, 333-38).

The idea that Saigõ was alive and returning to Japan from Russia was absurd,

and much newspaper reporting was tongue-in-cheek. The Niigata newspaper

Hokushin shinbun, for example, sponsored a contest in which readers could

vote for whether Saigõ was alive or dead. (Kusunoki 1997, 23). Fukuzawa

Yukichi, writing in the Jiji shinpõ on April 10, ridiculed the legend but used it

This content downloaded from

117.240.50.232 on Thu, 14 Jan 2021 12:50:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Apocryphal Suicide of Saigö Takamori 715

as an opportunity to critique the Meiji government. While some were terrified

that Saigõ might exact vengeance on his old enemies, Fukuzawa did not think

that Saigõ would stay for long: he would take one look at the Meiji government

and flee in disgust. The spendthrift decadence of the Meiji elite would drive

Saigõ, a man of genuine simplicity and humility, straight back to hell (Fukuzawa

2002, 9:95-98). This arch tone was attributed even to the Meiji emperor. Accord-

ing to the April 7 Chõya shinbun, the emperor joked that if Saigõ were indeed

still alive, the throne would have to take back the medals awarded after the

War of the Southwest (Sasaki 1994, 335).

These glib remarks had unexpectedly violent consequences. On May 11,

Tsuda Sanzõ, a constable and decorated veteran of the War of the Southwest,

attacked Nikolai as he was being escorted through the town of Õtsu on Lake

Biwa. Tsuda struck Nikolai twice, cutting two long gashes in the prince s head,

before being subdued by police. Tsuda s motivations were complex, and reflect

possible mental illness as well as the rise of fervent anti-Russian rhetoric. In pre-

trial hearings, however, Tsuda explicitly stated his belief that Saigõ was returning

with Nikolai and that this threatened his military honors (Kusunoki 1997, 22-23).

A veteran of some of the fiercest fighting of the war, Tsuda had received not only

a medal, but an award of 100 yen (Õtsu-shi rekishi hakubutsukan 2003, 42-43). 13

Tsuda s spectacular outburst, together with widespread reports that he was

insane, helped relegate Saigõ survival stories to the realm of novelty and mythol-

ogy. Tales of Saigõ s survival gradually became associated with other Japanese fan-

tasies of escape and transformation, such as the legend that Minamoto no

Yoshitsune fled to Mongolia and became Chingis Khan. Nonetheless, they sur-

vived in alternative media, such as adventure novels for young boys. In Oshikawa

Shunrõs Shin Nihon tõ (1906), for example, Saigõ survives the Battle of Shir-

oyama and leads a liberation army against American imperialism in the Philip-

pines (Karlin 2002, 74-75; forthcoming).

Popular fiction kept alive the dual meanings of Saigõ as both a progressive

leader and a militarist. A 1912 article in the boys' magazine World of Adventure

(Bõken sekai) posed the question, "what if Saigõ had won?" Saigõ, the author

argued, would have quickly built a continental empire, conquering not only

Korea, but also Manchuria and northern China. At the same time, however,

Saigõ would have pushed for constitutional government, including a representa-

tive assembly. "Didn't Saigõ submit a memorial for a representative assembly

(minsen giin) in 1873? He was an associate of Fukuzawa Yukichi and he

thought seriously and with firm convictions about civil government." Saigõs

concern for ordinary people, his lack of interest in noble titles, and his ardent