Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Copula Clauses in Australian Languages - A Typological Perspective (Anthropological Linguistics, Vol. 44, Issue 1) (2002)

Uploaded by

Maxwell MirandaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Copula Clauses in Australian Languages - A Typological Perspective (Anthropological Linguistics, Vol. 44, Issue 1) (2002)

Uploaded by

Maxwell MirandaCopyright:

Available Formats

Trustees of Indiana University

Anthropological Linguistics

Copula Clauses in Australian Languages: A Typological Perspective

Author(s): R. M. W. Dixon

Reviewed work(s):

Source: Anthropological Linguistics, Vol. 44, No. 1 (Spring, 2002), pp. 1-36

Published by: The Trustees of Indiana University on behalf of Anthropological Linguistics

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30028823 .

Accessed: 08/01/2013 09:09

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Trustees of Indiana University and Anthropological Linguistics are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to Anthropological Linguistics.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Copula Clauses in Australian Languages: A Typological Perspective

R. M. W. DIXON

ResearchCentrefor Linguistic Typology,La Trobe University

Abstract. Copula clauses are distinguished from transitive and intransitive

clause types. They have two core arguments, copula subject (CS) and copula

complement (CC), together with a copula verb (which may sometimes be

omitted). A general characterizationof copula clauses is presented, in terms of

syntax, form,meaning, and occurrence.For a verbto be identifiedas a copula,it

must occurwith these two core arguments (CS and CC) and show a relation of

identity/equation or of attribution. It may also have some or all of the senses:

location, possession, wanting or benefaction, and existence. The copula verbs

reported in the literature on Australian languages are then summarized, and

the analytical problems associated with them are discussed. These problems

include: whether verbless and copulaclauses should be combinedas one clause

type, the difficulties associated with attribution, the need to distinguish

between a copulaverb and an inchoativederivationalsuffix, and the distinction

between the existential use of a verb of rest or motion and a copula verb. It

appears that Australian languages show a recurrenttendency to create copula

verbs (generally,by grammaticalizationof stance verbs 'sit', 'stand', and 'lie', or

of 'stay' or 'go'), and also that the propertyof having a copula clause type tends

to diffuse from language to language, within the continent-wide Australian

linguistic area.

1. Introduction. There are two major clause types found in human languages,

transitive clauses and intransitive clauses. In addition, many languages have a

further clause type, copula clauses. The makeup of the three clause types is

shown in table 1.

Table 1. Basic Clause Types

CLAUSETYPE NUCLEUS COREARGUMENTS

transitive clause transitive predicate transitive subject (A) and

transitive object(0)

intransitive clause intransitive predicate intransitive subject(S)

copula clause copula verb copula subject (CS) and

(copulapredicate) copula complement(CC)

Whereas transitive and intransitive verbs have referential meaning, copula

verbs have relational meaning. We show below that for a verb to be recognized

as a copula, it must be able to occur with two core arguments, namely, the

copula subject (CS) and copula complement (CC), and the CC must indicate a

relation of identity/equation or a relation of attribution.

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2 ANTHROPOLOGICALLINGUISTICS 44 NO. 1

There may also be verbless clauses, which simply include two NPs in juxta-

position. Languages which lack a copula verb typically translate copula clauses

from other languages with verbless clauses, e.g., '[John][a doctor]'for 'John is a

doctor'. In many languages, including those of Australia, copula clauses and

verbless clauses may be regarded as variants of one clause type. However, it

must not be assumed that this holds for all languages which have both copula

and verbless clauses; in some instances, there may be grammaticalor semantic

reasons for distinguishing two distinct clause types.

The nucleus of a transitive clause will prototypicallyhave a transitive verb

as head (in some languages the head can only be a transitive verb). Languages

show more variationwith respectto the predicatehead in an intransitive clause.

In some languages only an intransitive verb can fill this slot; in other languages

the head of an intransitivepredicatemay be a noun or a pronoun or even an NP.

For example, in Boumaa Fijian one can say (1) below.

(1) [sa [marama savasavaa]AD sara gaa]mDICATE (Boumaa Fijian)

ASPECT lady clean VERYEMPHATIC

[o Aneta]s

name

ARTICLE

'Anetais a verycleanlady.'(lit.,'Anetaclean-ladiesvery.')(Dixon1988:66)

This is an intransitive clause with o Aneta as the S argument. The predicate

head here is an NP consisting of noun marama 'lady' and adjective savasavaa

'clean'. It is flanked within the predicate by modifiers (just as a verb in this slot

would be): the aspect marker sa, here referringto an actionwhich is just coming

to an end (Aneta had just completed her bath when this sentence was uttered)

plus sara and gaa which together have an intensive sense. Although the

idiomatic translation is 'Aneta is a very clean lady', in fact the NP marama

savasavaa functions as predicatehead (like a verb),literally, 'Aneta clean-ladies

very'.

It is important to distinguish between an intransitive clause like (1), where

an NP functions as predicate head, and a copula clause where the same NP

might function as a core argument in copula complement function. We can

compare the two clause types in Tariana,a language fromthe Arawak family, as

shown in (2a) and (2b).

(2a) iari(-ne)s kuphe-pidanaNTRANREDIAT (Tariana)

man(-FOCUS) FISH-REMOTE.PAST.REPORTED

'A man was a fish.' (Aikhenvald forthcoming, p.c.)

(2b) 'iari(-ne)cs kuphecc di-dia-pidan&COPULA.VERB (Tariana)

man(-FOCUS) fish 3SG.NONFEM.CS-become-REMOTE.PAST.REPORTED

'A man became a fish.' (Aikhenvald forthcoming, p.c.)

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 R. M. W. DIXON 3

Both clauses refer to the kind of transmutation which can occur in a myth. In

(2a), the noun kuphe 'fish' is head of the intransitive predicate, and takes a

tense-evidentiality suffix (just as a verb would do in this slot). In (2b), kuphe is

the copula complement, an argument outside the nucleus of the clause; the

nucleus is here copula verb -dia-'become', and it is this which carries the tense-

evidentiality suffix.

The possibilitiesfor case marking on NP arguments in Tarianaare shown in

table 2.

Table 2. Tariana Case Marking

A, S, CS focussubjectmarker-ne (optional) -

0, noncorearguments - topicalnonsubject

marker-nuku

CC

That is, both S in the intransitive clause in (2a) and CS in the copula clause in

(2b)may take the suffix -ne, if that NP is in focus. The NP kuphein (2b) is in CC

function and may take neither the suffix -ne nor the suffix -nuku. Note that it is

not possible to treat (2b) as a type of extended intransitive clause, with &iAri

'man' as S argument and kuphe as an oblique argument; if this were a valid

analysis then kuphe should be able to take the topicalnonsubjectmarker-nuku,

which in fact it cannot do.

In Fijian, an NP functioningas head of an intransitive predicatecan take all

the modifiers available for a verb in this slot. In Tariana, a nominal as head of

an intransitive predicatetakes tense-evidentiality,mood,aspect, and most other

suffixes that would be available for a verb in the slot. Different types of clause

nuclei have varying properties with respect to prefixes; in brief, pronominal

prefixes are used with transitive and with active intransitive (Sa)verbs and with

the copula verb -dia 'become', but not with stative intransitive (So)verbs, nor

with the copula verb alia 'be', nor with nominals as head of an intransitive

predicate.

Suppose that there was a language like Tariana but with the additional

property that a copula verb may optionally be omitted. There would still be a

clear distinction between a clause with a noun as head of the intransitive pre-

dicate, as in (2a), and a copulaclause with the copula omitted, such as (2b) with-

out di-dia-pidana. In the first clause the noun kuphe'fish' takes a fair selection

of the affixes availableto a verb as predicatehead; in the second example kuphe

takes none of these (in fact, as a CC in Tariana, it cannot take any affixes).

A comment on terminology is in order. The term "predicate"was originally

used, in Greek logic, for everything in a clause besides the subject. The proto-

typical use of "predicate"in modern linguistics is for transitive or intransitive

verb, plus modifiers, but not including any NP.1 In the approachfollowed here,

the CC is a core argument, similar to A, O, S, and CS, so that it would be

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

4 LINGUISTICS

ANTHROPOLOGICAL 44 NO. 1

unhelpful and misleading to refer to it as the predicate or as part of the

predicate (as has sometimes been done). That is, it would not be helpful to say

that kuphe is head of the predicate in (2a) and part of the predicate in (2b) (the

full predicate here being kuphedi-dia-pidana), instead of saying that it is here

the copula complement argument. If the term "predicate"should be used of a

copula clause then its best employment would be to describe the copula (e.g.,

di-dia-pidana in (2b)). However, in the interests of clarity, it seems best not to

use the term "predicate"at all in connection with copula clauses.

The literature on Australian languages includes only occasionalreferences

to copula clauses, their properties, and the analytic problems associated with

their recognition. This article aims to redress the situation. But before the dis-

cussion of copulas in Australian languages, in section 3, we need to summarize

and clarify the general properties of copula clauses.

2. The character of copula clauses. I here outline four aspects of copulas:

their syntax, form, meaning, and occurrence.

2.1. Syntax. A copula clause involves two core arguments, like a transitive

clause. However, copula subject (CS) cannotbe identifiedwith transitive subject

(A), nor copula complement (CC) with transitive object (0). And, as just ex-

plained for Tariana, neither can a copula clause be identified as a type of in-

transitive, with the CS correspondingto S function and the CC being an oblique

argument, since the CC is a core argument, and the possibilities for CC are

different from those applying at any obliqueposition.

We can now examine the types of marking found on CS and on CC.

2.1.1. Marking on CS. In the great majorityof languages, CS is marked in the

same way as S, both in terms of case affixes or clitics on an NP (in dependent-

marking languages) and in terms of boundpronominalmarking on the verb (in

head-marking languages). In languages with split-S marking (Dixon 1994:71-

78), the CS is generally marked like So,rather than like Sa*

There are, however, occasional exceptions. These include:

(i) In Ainu, a head-markinglanguage with basically accusative morphology,

CS is marked in the same way as A, and differently from S, as shown in table 3.

Table 3. Ainu Case Marking

withintransitivesubject(S):ku-mina 'I laugh' mina-as(-pa) 'we laugh'

withcopulasubject(CS): ku-ne'I am' ci-ne(-pa) 'we are'

with transitive subject (A)

(0 is here3SG): ku-nukar 'I see him/her/it' ci-nukar(-pa)'wesee him/her/it'

SOURCE:

Tamura (2000:50-51).

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 R. M. W. DIXON 5

It will be seen that while prefix ku- is used for first-personsingular in S, CS, and

A functions, with first-person plural we have prefix ci- for CS and for A, but

suffix -as for S.

Note that while CS is marked like A in Ainu, CC is not treated like O. A

transitive verb takes pronominalprefixes marking A and O arguments (the O

prefix is zero for third-person), but a copula verb simply has one pronominal

prefix, for CS.

(ii) There are a few languages in which nominative (for S and A funptions)is

the formally and functionally marked case, while accusative (for O function) is

unmarked. This "markednominative" system is found in some languages from

the Berber and Cushitic branches of the Afroasiaticfamily, in North Africa, and

in some from the Yuman family (centered in southern California);see Dixon

(1994:63-67). In at least some of these languages the CS argument takes accusa-

tive case, the same as O in a transitive clause. In Kabyle, a Berber language,

both CS and CC are in the unmarked accusative case (Vincennes and Dallet

1960:99), while in Mojave,a Yumanlanguage, CS is in the unmarked accusative

and CC in the marked nominative case (Munro 1976:269-70).

(iii) In some languages, the CS in a positive clause is marked like S, but

takes some quite different marking in a negative copula clause. For instance, in

a negative clause, CS takes partitive case in Finnish and genitive case in Rus-

sian (these cases are used to mark a type of object in the two languages).

Other languages mark CS in the same way as S, even when there are a

number of alternatives for S. For example, in Mingrelian (from the Kartvelian

family), both S and CS take nominative case in three of the tense series, and

both take narrative case in the fourth series (Harris 1991:375-76).

It would be interesting to investigate, on a crosslinguistic basis, the syn-

tactic functionof CS in terms of constituent order,verbal agreement, constraints

on coordinationand subordination,etc. Little work has so far been done on this

topic. Interestingly, a CS markedby genitive case in a negative copulaclause in

Russian does share subject properties with S and A, in the same way that a CS

marked by nominative in a positive clause does. However, Sands and Campbell

(2001) suggest that in Finnish a CS marked by partitive case in a negative

copula clause shows fewer subject properties than a CS marked by nominative

case in a positive clause.

2.1.2. Types of CC. There are typicallya range of possibilities at CC, correlat-

ing with the different types of relation that a copula may represent. The main

ones are:

(a) A relation of identity (e.g., 'he is a doctor')2 or equation (e.g., 'that man is

my father'), involving an NP as CC.

(b) A relation of attribution (e.g., 'I am tired', 'that picture is beautiful'),

involving an adjective or a derived adjectival expression as CC.

(c) A relation of location (e.g., 'I am here', 'John is from Ramsbottom', 'the

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

6 ANTHROPOLOGICAL

LINGUISTICS 44 NO. 1

dog is in the garden'), involving as CC a local adverb or an NP marked with a

local case or adposition.

(d) A relation of possession (e.g., 'That car is John's'), involvingas CC an NP

with genitive marking.

(e) A relation of wanting or benefaction, etc. (e.g., 'Who'sfor tennis?', 'This

cake is for John'), involving as CC an NP with dative or similar marking.

There may well be further possibilities for relations expressed by copula

verbs, which would turn up in a fuller survey of grammaticaldescriptions than

has been attempted here. In addition, there is a further, nonrelational, type of

meaning that a copula clause can represent:

(f) Existence, with just one core argument, in CS function.

In some languages,both CS and CC of type (a) or (b) are marked in the same

way, so that a copula clause can include two NPs in nominative case (in an

accusative language) or two NPs in absolutive case (in an ergative language).3

There are languages in which a CC of type (a) or (b) is markedin a different

way fromany argument in a transitive or intransitive clause (and also different-

ly from CS). For example, in Japanese a CC does not take any postposition,

unlike all other core and peripheral NPs. As mentioned above, in Tariana a CC

is the only kind of NP which cannot take any case marker. In English, an adjec-

tive (without any article or dummy head noun) can occur as a CC in an attribu-

tive copula clause, but would not be acceptablein A, O, S, or CS function.

In Jarawara (Arawi family, Brazil; Dixon forthcoming) the pronominal

paradigm for CC is different from that for any other core argument, as shown in

table 4.

Table 4. Jarawara Pronominals

A,S, CS O CC

1SG o- owa owa

2PL tee tera tee

For singular pronouns CC has the same form as 0, and for plural pronouns it

has the same form as A, S, and CS.

Another language in which CC has a different form from other NP argu-

ments is Zayse, from the Cushitic branch of Afroasiatic(Hayward 1990:266). A

sample paradigm of pronouns is shown in table 5.

Table 5. Pronouns in Zayse

A, S, CS O CC WITH

POSTPOSITION

1SG taDjJ tina tinte tia(-ro)

2SG nefl nena rnente nee(-ro)

SOURCE:

Hayward (1990:226).

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 R. M. W. DIXON 7

We find furtherpossibilities in individual languages and linguistic regions.

For example, in a number of east European languages the CC in an equational

copula clause can be marked either by nominative case or by an oblique case,

with a difference in meaning. Nominative indicates a permanent relation (e.g.,

'he is a cleaner' as a profession), whereas oblique marking refers to something

that is temporary(e.g., 'he is a cleaner'as a fill-injob).The obliquecase involved

is essive in Estonian and instrumental in Russian (see also Comrie [1997:40]on

Polish).

One interesting propertyof copula clauses is that the CC is seldom (perhaps

never) marked by a bound pronominalattached to the verb. Even in a language

such as Yimas (Papuan area), where A, S, O and indirect object are marked on

the verb, in a copulaclause only CS, not CC, is included in the system of bound

markers (Foley 1991:193-226).

The possibilities for CS may also vary depending on the kind of relation

expressed. In English, for instance, a demonstrative (this/these, that/those)

which has animate reference can be in CS function only if the copula clause

indicates a relation of equation (e.g., This is my father). For other kinds of rela-

tion, a demonstrative with animate reference, in CS function, must be accom-

panied by something like one (e.g., this one is beautiful, not *this [animate

reference] is beautiful).

A defining criterion for a copula is that it should take two core arguments,

CS and CC. In some languages (including English), a copula requires CS and

CC. However, in other languages, there is an alternative copula constructionin

which the CC is omitted. This applies to Ancient Greek (where one can say 'god

is' with the meaning 'god exists, there is a god'), and also to Jarawara. Compare

(3a), a canonical copula clause including both CS and CC, with (3b), a reduced

copula with only one NP, in CS function.4

(3a) birotocc ama o-ke (Jarawara)

pilot be 1sG.CS-DECLARATIVE+FEMININE

'I am a pilot.'

(3b) okasimacs ama-ke (Jarawara)

be-DECLARATIVE+FEMININE

1SG.POSSESSIVE+younger.sister

'I havea youngersister.'(lit.,'Myyoungersisteris.')

Example (3b) shows a copula clause of type (f), existence, with just the CS.

If a putative copula always occurswith just one core argument, CS, and not

also with a CC,then it is not a copula verb at all, but a straightforwardintransi-

tive verb.5 If a putative copula verb occurs just in relation (c), with an NP

marked by a local case (and assuming that CS is marked in the same way as S),

then it should be regarded as an intransitive verb with an oblique, local NP.

Similarly for a putative copula which occurs only in relation (d) or (e), with a

genitive or dative NP.

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

8 ANTHROPOLOGICAL

LINGUISTICS 44 NO. 1

That is, for a verb to be identified as a copula, it must occur with two core

arguments, CS and CC, with CC including at least the identity/equation rela-

tion, (a), or the attribution relation, (b).

2.2. Form. In its morphological properties, a copula is seldom exactly like

members of the class of intransitive and transitive verbs. In some languages it

has more forms than other verbs. This applies in English, where there is person

marking in am/are/is and in was/were, and in Hindi (Kachru 1968:41).In other

languages the copula shows fewer forms than other verbs. In Turkish, for in-

stance, it has fewer TAM distinctions, lacking progressive, future, and aorist

(Lewis 1967; Geoff Haig p.c.), and in Modem Greek it makes no aspectual

distinctions (Joseph and Philippaki-Warburton1987:196).

The copula is frequently irregular in its forms. Indeed, Foley states that in

Yimas "the copulais the only truly irregularverb, and it is highly so" (1991:226).

There are suppletive stems of the copula in a number of languages, including

Kurukh, from the Dravidian family (Vesper 1968), and Mundari, from the

Munda branch of Austroasiatic (Langendoen 1967).

2.3. Meaning. It is often said that a copula verb does not have meaning. By

this is meant that it does not have any referential meaning; one cannot point to

an action or state as referent of 'be' in the way that one can for 'walk' or 'talk' or

'annoy'.

What a copulaverb does have, in any instance of use, is a relational meaning

of one of the types listed above. That is, it can establish a relationship between

CS and CC of (a) identity or equation,(b) attribution,(c) location, (d) possession,

or (e) wanting or benefaction. I mentioned that some languages have mono-

valent use of a copula verb, indicating (f) the existence of the referent of the CS;

this is effectively ascribing a propertyto the CS.

The set of relations espoused by a copulavaries from language to language.

I showed in section 2.1 that a verb must have sense (a) or (b) to qualify as a

copula; otherwise it should be placed in the class of intransitive verbs. In some

languages it just shows relation(a) or (b) or both, but in others it may exhibit the

whole range (a)-(f), and sometimes more besides. It is possible that a language

might have different copula verbs for functions (a) and (b), but none have been

reported thus far.6

In some languages, including English, there are two copulas, 'be' and

'become', with the 'become'form generally only being used for relations (a) and

(b). The difference between them lies in the temporal nature of the relation-

temporally static for 'be' (as in 'my son is a doctor', 'my son is fat') or temporally

incremental for 'become' (as in 'my son became a doctor', 'my son became fat').

In other languages a single copula may correspond to both 'be' and 'become'.

There can be other semantic parameters applying to copulas in relations (a)

and (b). A recurrent copula is 'be like', a modification of the equation relation.

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 R M. W. DIXON 9

One commondiachronicsource for copulas is verbs of motion and rest such

as 'go' or 'stay' and stance (or position) verbs such as 'sit', 'stand', and 'lie'.7

Criteria for a certain verb being used as a copula verb rather than as an

intransitive verb of stance are (i) that it should occur with two core arguments,

CS and CC; and (ii) that it should no longer have a stance, or any other,

referential meaning,but instead just indicate a relation holding between CS and

CC. In some languages a certain form can do double duty, both as a verb of

motion or rest and as a copula verb. We return to this during the discussion of

Australian languages, in section 3.4.

2.4. Occurrence. Some languages lack any copula verb and express relation-

ships such as (a)-(f) through simply juxtaposing NPs and by using intransitive

verbs. At the opposite extreme, there are languages in which every full clause

(that is, excludingcommentsand replies) must include a verb, so that there can-

not be a clause consistingjust of two NPs; English, Finnish, and Jarawara are of

this type.

In a number of languages, a copula verb is optionally omittable in every

circumstance (it appears that the Dravidian language Malayalam is like this

[Asher 1968:97]). In others, it may be omitted in certain circumstances. For

example, in Hungarian, the copula is omitted in present tense when the CS is

third person and the CC relates to identity/equation, or attribution (but is

included when it relates to location or possession). In Russian, the copula must

be included in past and future tenses but is generally omitted in present tense; it

is retained only in high-flown language and in mathematical formulae(and the

present copulahas a single form, based on the old third-personsingular, where-

as in past and future tenses the copula agrees with the CS in number and in

person or gender).There is a differenttype of omissionin Sumerian;here a verb

canonically takes a TAMverbal prefix, but the copula 'be' omits this prefix and

is then encliticizedto the precedingCC.This cliticization is optional if the CC is

an NP, and obligatoryif it is an adjective (Gragg 1968).

The occurrence and form of a copula may depend on other grammatical

features of the clause. In Turkish, for instance, there are no negative copula

constructions (a negative verbless clause must be used). Some languages have

different forms of the copula in positive and negative clauses; for example, in

Koromfe (a Gur language), the positive copula has form la and the negative one

has form do (Rennison 1997:61).

A common explanation offered for the omissibility of a copula verb is that

the copula is, effectively, a "dummy"element needed just to carry bound mor-

phemes providing information about TAM, person and number of CS, etc. In this

view, the copulacan be or must be omittedin the context of the unmarked choice

from a certain grammatical system. For example, if present is the functionally

unmarked term in the tense system, then the copula may be omitted in present

tense; its lack will signal that the clause is in present tense. And if third-person

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

10 LINGUISTICS

ANTHROPOLOGICAL 44 NO.1

singular is the unmarked term from the pronominalsystem, then a copula may

be omitted when CS is third-person singular.

Many languages permit both copula clauses and verbless clauses. In some

instances these should be recognized as distinct clause types, but there may be

points of similarity between them. In Chukchi, one type of negator is used for

both verbless and copula clauses and another type for intransitive and transi-

tive clauses (Dunn 1999:325-40). If a language which permits the copula to be

omitted (in all circumstances, or just under specified conditions) also shows

verbless clauses, then it may be difficult or impossibleto distinguish between a

copula clause with the copula omitted,and a verblessclause.This is discussed in

section 3.1, in connectionwith Australian languages.

3. Copula clauses in Australian languages. I know of no Australian

language in which a nominal or an NP can function as the nucleus of an

intransitive clause, on the pattern of (1) in Fijian and (2a) in Tariana.

All Australian languages have verbless clauses, made up of just two NPs. A

fair number of them also have copulaclauses. In every such language the copula

verb is optional in many circumstances. Thus in many (perhaps in all) Aus-

tralian languages it is most appropriateto recognizecopula clauses and verbless

clauses as varieties of one clause type. This has the structure:

+Copulasubject(CS) +Copulacomplement(CC) Copula verb

In many languages, a copula is more frequently omitted than included. Thus,

Hosokawa states that, in Yawuru, "copulasare usually left out" (1991:456).

The marking of CS and of CC is, with a couple of exceptions, straight-

forward. CS is marked in the same way as S, by absolutive or nominative case

(which is generally zero). A CC of type (a), indicating identity/equation, or of

type (b), indicating attribution is also marked like S. CCs of other types receive

the appropriatefunction marker: a local case for (c) locationalrelation; genitive

suffix for (d) possessive relation; and dative or a similar case for (e) wanting/

benefaction relation.

One of the exceptions concerns Diyari. Austin states that if the CC is one of

a set of nominals referring to "moreor less temporary mental or physiological

states" (1981a:104-5), then it takes ergative case marking, as in (4).

(4) nganhics mawa-licc ngana-yi (Diyari)

1SG hunger-ERGATIVE be-PRESENT

'I am hungry.' (Austin 1981a:105)

The other forms selecting ergative include 'sleep', 'fear', 'danger', 'sadness',

'jealousy', 'strength', and 'cold'. Breen (2001) reports a similar structural

pattern in the neighboring language Yandruwanhdha, involving copula verb

ngana-'become' (which can also function as an intransitive verb 'do' and as a

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 R. M. W. DIXON 11

transitive verb 'tell');the CCs which take ergative-instrumentalcase in Breen's

data include 'fear', 'aggression', and 'cold'.

The second exception occurs in Djingulu, a language which has no copula

verb. But in a verbless clause there are different possibilities for CS depending

on the nature of the CC. If the CC is an NP (in an identity/equation relationship

with CS) then CS is in ergative case, like A (reminiscentof CS marking in Ainu,

mentioned in section 2.1.1). And if the CC is an adjective (in attributional

relation to CS) then CS is in absolutive case (with zero marking), like S. In each

instance, CC is in absolutive case. Compare(5a) and (5b).

(5a) njamina-nics wamalagardimicc (Djingulu)

THAT+FEMININE-ERGATIVE

virgin

'She's a virgin.' (Pensalfini 1997:187)

(5b) [njima babirdimi]s kiyaljiyanucc (Djingulu)

THAT+VEGETABLE yam rotten

'That yam is rotten.' (Pensalfini 1997:186)

One topic for future research concerns the syntactic behavior of CS. For

example, some Australian languages have a switch-reference system whereby

different suffixes are used to show whether two clauses making up a complex

sentence construction have "same subject" or "different subject" (see Austin

1981b). Does "subject"here include CS, in addition to S and A? And does CS

function in the same way as S in a language with an S/O pivot, and in a lan-

guage with an S/A pivot?The indicationsare that the answers to both questions

are in the affirmative,but detailed work is needed to confirmthis.

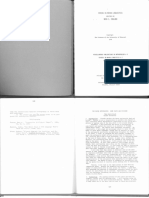

The copulaverbs reportedfor Australian languages are summarized in table

6. The first column provides a code symbol for each language, in terms of the

grouping followedin Dixon (2002);this relates to map 1, and is briefly explained

in section 3.8. The second column gives the language or dialect name and

sources. The next column lists the copula(s), with information on any homony-

mous verb in that language or cognate in another language. The final six

columns provideinformationas to the relational senses of each copula, in terms

of (a)-(f) from section 2.1.2. (The plus signs enclosed in parentheses in column

(c) are explained in section 3.5 below.)8

It should be noted that many grammars only mention copulas in passing,

without any explicit details of criteria, or full statement of relational senses. As

a consequence,only some of the forms that have been describedin the literature

as copulas qualifyas copulas in terms of the criteriafollowed in this article. In a

fair number of sources, only a few example sentences are provided. The plus

signs in columns (a)-(f) are based on the actual instances of copula clauses

provided in the literature.

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

(f) +

(e) + +

(d)

(c) + + + + +

FUNCTIONS

(b) + + + + + + + + + + + +

(a) + + + + + + + + +

'lie')

verb one's

on

languages);

'lie

nearby 'sit') nearby

verb

intransitive in in

languages) verb

(also

'sit') 'stand' 'stand' 'go')

only nearby 'leave')

intransitive

verb in with with verb

Languages verb

intransitive (also

speakers

with'sit' (cognate(also

HOMONYMS/COGNATES like'

(cognate

intransitive transitive intransitive

AND given

Australian become'

younger

in (also (cognatebecome' become'(also

become' (also

VERBS for

'be,

Verbs examples 'be' 'be'

'become'

wu-'be', wiyi-'be'

nhin-'be' languages)

barda-'become'

wara-'be, no

ngine-wana-'be'

yia-/ye-'be,wara-'be,back')

gingggi-'be/become

yana-'be'

COPULA ga- gi- ngi-

Copula 527)

of

1981:348)

1983: 168)

dialects 39-47, 517-19,

72,

1998:52-53) Geytenbeek

SOURCES 131-32;

Holmer and 1846:497-99,

Occurrences Gunja 43-44)

AND 1979:117-18) 1834:34, 1980:68-70)

Terrill 1948-49:71)

1991:389)

Yimidhirr and1973:187-18, 1983:68, Hale

1974; 1846:497-99,

2000:105,

Attested

Guugu

6. LANGUAGE(Haviland

Yir-Yoront

(Alpher

Bidjara

(Breen

Biri

(Beale

267-388,

(Kite

Waga-Waga

Holmer 1971:26-27,

Gidabal/Bandjalang

(Geytenbeek 105-31;

Gumbaynggirr

(Smythe Yuwaalaraay

(Threlkeld (Williams

517-19)

Awabagal (Hale

Wiradhurri

Table

CODE Dd1 Ebi Jal Ja2 Ma4 Mf Mgl Nal Ndc Nc2

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

(f) + + +

(e)

(d) + +

(c) (+) (+) (+) (+) + (+) +

FUNCTIONS

(b) + + + + + + + + + + +

(a) + + + + + + + + + +

transitive

and

remain')

'do'

(continued) 'sit') 'sit,

verb

'sit') 'stand')

'stand')

verb verb

verb verb

verb

Languages

intransitive

HOMONYMS/COGNATES intransitive

intransitive

(also

intransitive intransitive

AND intransitive

(also (also

Australian (also (also

in (also

VERBSbecome'

become' 'be' 'become' 'tell')

'be,

Verbs

COPULA

ga- yi-'be,yuma-'be' nhengka-'be'

gurri- kana- verbngana-'be'

tharznga-'be'

nhina-'be'

ngana-'become' ngara-'be'

panjtji-'become'

yuga-'be'

Copula

of 1979b:

and

1981a: Eckert

Blake

Blake

SOURCES language

35; p.c.)

1980) 1988:51-52)

AND

Occurrences 1985:38-39;

1986:47) 1994:295) Desert

1999:136-37)

1978:238-40,

1988) 1991:76-78)

1971:66-67;

1897:5, 2001,

223) Hudson

Attested

LANGUAGE

(Donaldson

Ngiyambaa

Muruwarri

(Oates

(Hercus

Wemba-Wemba Pitta-Pitta

(Roth

Wuy-wurrung

(Blake Breen (Hercus 104-6)

210,Arabana/Wangkangurru

(BreenDiyari

Yandruwanhdha

(Austin

Wirangu

(Hercus and

Western

(Goddard

Table.

CODE Nc3 Nd Tal Ta3 WAal WAa3 WAbl WAb2 WC WD

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

(f) + +

(e) +

(d) +

(c) (+) (+) +

FUNCTIONS

(b) + + + + + + + + + + + +

(a) + + + + + + + + + +

at')

be

cognate

remain,

exist')

live,

(continued) exist')

verb'stay';

'stay, dwell') verb'stay,

'sit') 'sit') 'stay, 'sit') 'go')

'sit')

'sit') 'live, CC)

verb verb

verb verb verb

verb'go') verb to

Languagesverb

intransitive verb verb

intransitive

languages)

HOMONYMS/COGNATES (also

intransitive (also (cliticized

intransitive

intransitive

intransitive

intransitive intransitive

other intransitive

AND intransitive

Australian in intransitive

intransitive

in (also (also (also (also

(also become'(also (also

(also become'

VERBS (also (also

'stand'

Verbs

njin-'be'

COPULA njina-'be' wani-'be'

panti-'be'

puni-'be' nguna-'be' withnjina-'be'

karri-'be, ne-'be'kuna:- wirdija-'become'

=me-'be,

-yang-'be'

Copula

of

1990:194)

1983:111; 437-29)

p.c.) p.c.) 119)

83)

Kangka

SOURCES

Hudson

Occurrences

AND 1990) forthcoming)

1976:66, and

1978:94-95, 1989:220-23,

1995:209-13,

1991:184-85, 1997:164) 1983:57-58,

1995:321-23) 1986:258-60)

1998:442-43)

Attested

6. LANGUAGE(Douglas

Nyungar Panyjima

(Dench

Martuthunira

(Dench Njangumarta

(Sharp(Hudson

Richards

Gurindji

Walmatjarri Warlpiri

(Laughren

(McConvell Lardil

(Wilkins

Arrernte (Ngakulmungan

Leman

Kayardild

(Evans(Merlan

Ngalakan

Warray

(Harvey

Table

CODE WF WHc2WHc3 WIal WJal WJa3 WJbi WL1 NAa NAbi NBc2 NBh2

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

(f) +

(e)

(d)

(c) + (+)

FUNCTIONS

(b) + + + + + + +

(a) + + +

'lie')

meaning

with

(continued) verbs,

'sit') 'sit')

'lie') 'go')

verb'go')

verb verb

Languages

compound verb verb

some

HOMONYMS/COGNATES

in

intransitive

intransitive

intransitive intransitive

AND used intransitive

Australian(also

(also (also become'

in

(also (also (also

VERBS

'be'

Verbs

-yi-'become'

COPULA mirra-ngara-'be,

-jingi-'be'

-yu-'be' bagi-'be'

-buy-'be'

Copula

of

SOURCES

Occurrences

AND

1998:178-79)

(Guniyandi)

1991:456)

1990:310-11)

1992:379)

1994:212-13) 1990:129)

Attested

Gaagudju

6. LANGUAGE(Harvey

Wardaman

(Merlan

Wambaya Gooniyandi

(Nordlinger

Yawuru

(Hosokawa (Harvey

(McGregor

Kamu

CODE NBk NBI2 NCb3NE1 NF2 NHe2

Table

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

16 LINGUISTICS

ANTHROPOLOGICAL 44 NO. 1

We can now consider some of the special features and analytic problems

associated with copula verbs in Australian languages.

3.1. Copula clauses and verbless clauses. We can roughly distinguish

three types of language:

(i) With one copula verb coveringboth 'be' and 'become';it may optionallybe

omitted.

(ii) With two copula verbs, one for 'be' and one for 'become'; each may

optionally be omitted.

(iii) With a copula verb for 'become',but using a verbless clause for 'be'.

Type (iii) can be exemplified by Yuwaalaraay (Williams 1980:69).Compare

the verbless clause in (6a) with the copula clause in (6b).

(6a) burulac [nhama dhayn]cs (Yuwaalaraay)

big THAT man

'Thatman is big.' (Williams1980:69)

(6b) burulcc [nhama dhayn]cs gi-nji (Yuwaalaraay)

big THAT man become-NONFUTURE

'Thatman is gettingbig.' (Williams1980:69)

It is likely that other languages may be like Yuwaalaraay in using a verbless

clause for 'be' and a copula clause for 'become';there is just not enough inform-

ation on most of them to be able to tell.

It is relevant to inquire when a copula verb will be included and when

omitted, for a language of type (i) or (ii). This is surely not entirely a matter of

personal whim, but is likely to relate to discourse and pragmatic factors.

Nordlinger states that, in Wambaya,the copulaverb tends to be used "when

the statement is emphatic, or one of exclamationor contrast";in (7), the speaker

"hadjust taken a drink of what she was expecting would be tea" (1998:179).

(7) inics gi-n galjurringic mirra! (Wambaya)

water

THIS 3SG+PRESENT-PROGRESSIVE be

'Thisis water!'(Nordlinger1998:179)

Nordlinger also remarks that, for the adjectives 'good' and 'bad', use in a verb-

less clause implies an objective (or evaluative) meaning, while use in a copula

clause implies a subjective (or experiential) meaning, as in (8a) and (8b).

(8a) gurijbicc [ini alaji]cs (Wambaya)

good THIS boy

'This boy is good (i.e., in terms of behavior,temperament, etc.).' (Nordlinger 1998:

179)

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 R.M. W. DIXON 17

(8b) alajics gi gurijbicc mirra (Wambaya)

boy 3SG+PRESENT

good be

'Theboyfeelsgood.'(Nordlinger1998:179)

Some grammars suggest that the copula is included as a sort of dummy,

to take TAM or other affixes. For example, in Diyari an imperative involving

an adjective as CC requires a copula to host the imperative suffixes, as shown

in (9).

(9) wata malhanjtji ngana-a-ni-mayi! (Diyari)

NOT bad be-IMPERATIVE-NUMBER.MARKER-EMPHATIC

'Don'tbe bad!'(Austin1978:240)

Austin states that, in nonimperative clauses, ngana- is "onlyrarely used in the

present tense" but "when the attribute, equation or posessive equation is not

located in the present, ngana- must be used to carry the tense or mood inflec-

tion" (1981a:104).

As happens in languages from other parts of the world (see section 2.4), a

copula is likely to be omitted if referenceis to present time, but included-with

the appropriatetense suffix-for past or future reference. For example, Wilkins

states that, in Arrernte "all apparently verbless clauses must have present

reference and must take a copular verb marked for tense when the temporal

reference is other than the present" (1989:438). Other grammars have similar

accounts.

A copula can be included as an element to carry other types of verbal affix.

In Biri, for example, when the causative suffix -mba- is added to the copula

wara-'be' it derives a transitive verb 'make', as in (10).

(10) yabuna-ngguA wara-mba-li baladhao (Biri)

boat

father-ERGATIVEbe-CAUSATIVE-PAST

'[My]father made [this] boat.' (Beale 1974:16;repeated in Terrill 1998:52)

3.2. Attribution and copula clauses. As emphasized in section 2.1, one of

the tests for telling whether a certain form is to be regarded as a copula verb is

whether it may occur with the two arguments CS and CC. If it takes only one

argument, then it should be classified as an intransitive verb, not as a copula

verb.

In most Australianlanguages, both orderof phrases within a clause and also

order of words within a clause is fairly free. That is, in a clause such as 'big man

sat', the three words can potentiallyoccurin any order.This can make it hard to

decide on the status of a potential copula verb which is attested only in the

attribution relation (b). Consider the sentence from Gumbaynggirr in (11).

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

18 ANTHROPOLoGICAL

LINGUISTICS 44 NO. 1

(11) ngaya ya:ri da:ruy (Gumbaynggirr)

1SG be+PRESENT good

'I amgood.'(i.e.,'I amwell.') (Smythe1948-49:71)

This could be a copula clause, with ngaya as CS and da:ruy as CC. But it might

alternatively be an intransitive clause where the S argument is expressed by a

discontinuous NP ngaya da:ruy, with ya:ri here being an intransitive verb (lit.,

'[I good] is').

The way to decide whether a certain verb is a copula is to obtain it in a

clause where the CC is a full NP, an example of the identity/equation relation

(a). For example, on searchingthrough the dictionaryof Yir-Yoront,we find the

sentence in (12).

(12) [pam-ngamayrr athan]cs Thayorrcc nhinl (Yir-Yoront)

PERSON-mother 1SG.POSSESSIVEname be+PAST

'Mymotherwas a Thayorr(a memberof a neighboringlanguagegroup).'(Alpher

1991:389)

This confirms that nhin- is here functioning as a copula.

At the end of section 2.1, the criterion given for a verb to be identified as a

copula was that it should occur in the identity/equation relation (a), or in the

attributive relation (b). In a language with free word order-as in many Austral-

ian languages-this needs to be restricted to just the identity/equation relation

(a). For most of the verbs given in table 6, we do have examples of usage in this

relation, confirmingtheir status as copulas. However,the data is scarce on some

languages, with only an attributive relation being attested; in such instances

the identificationas a copulaverb must be regarded as tentative. This applies to

wu- in Guugu Yimidhirr, barda- in Bidjara, yana- in Gumbaynggirr,gi- in

Yuwaalaraay, yuma- in Wemba-Wemba, gurri- in Wuy-wurrung, yuga- in

Wirangu, njin- in Nyungar, puni- in Martuthunira, nguna- in Walmatjari, -yi-

in Gaagudju, -jingi- and -yu- in Wardaman,and -buy- in Kamu.

3.3. 'Become' and inchoative derivational affixes. Almost all Australian

languages have an inchoativesuffix which, when addedto a nominal, derives an

intransitive verbal stem with the meaning 'become'. It can sometimes be a

tricky matter to distinguish between a copula verb 'become' and an inchoative

suffix 'become'.

In many Australian languages each word consists of at least two syllables,

and an affix can have one, two, or more syllables. Thus, if a form glossed as

'become' is monosyllabic, there is a high chance that it is an inchoative suffix. If

it has two syllables, then it could equally well be a copula verb or an inchoative

suffix.

For Pitta-Pitta there are two main sources. Roth (1897) was a local doctor

who evinced a keen interest in anthropology and linguistics. He worked with

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 R. M. W. DIXON 19

fluent speakers, at a time when the language was actively spoken, but his

grammar is short and lacks the methodological rigor of modern linguistics.

Blake and Breen worked with the last speakers, in the 1960s and early 1970s;

their work is of high standard but the data available was sketchy (Blake and

Breen 1971; Blake 1979b).

Roth states that "the verb 'to be' is in reality not expressed ... There is,

however, a verb kunna- [phonemically kana-] = 'to be' in the sense of 'to

become'" (1897:5). Blake (1979b:210) analyzes -kana as an inchoative verbaliz-

ing suffix, and provides two examples: one is attributional, 'become cold', and

the other equational, 'become a boy', shown in (13).

(13) karru-kana-ya nhari nhu-wa-ka rtakuku (Pitta-Pitta)

now

boy-INCHOATIVE-PRESENT 3SG.MASC-S-HEREbaby

'This baby is now getting to be a real boy.' (Blake 1979b:210)

Note that stress occurs on the first and third syllables of a word (but not on a

final syllable). Thus the stress pattern would be the same on kdrru-kina-ya (one

word, with -kana as a derivational suffix) and on kdrru kdna-ya (two words,

with kana as a copula verb). For Pitta-Pitta the data available does not permit

us to come to a clear decision as to whether kana should be regarded as a copula

verb 'become' (with karru 'boy' as the CC) or as an inchoative derivational

suffix, forming an intransitive verb karru-kana-'become a boy'.

There are several sources available for Bandjalang, a language which has a

fair number of distinct dialects. For the Gidabal dialect, Geytenbeek and

Geytenbeek (1971:43) recognize a number of copula verbs including ginggi-

'be/become like', as in (14).

(14) mugi:m-ngencs dubayoc gingge-:la (Gidabal dialect)

perch-PLURAL woman become.like-PRESENT

'The perch (fish) are becominglike women.' (Geytenbeekand Geytenbeek 1971:43)

However, Crowley (1978:91), in his grammar of the Middle Clarence dialects of

Bandjalang, recognizes -ginggi 'be similar to' as a derivational affix, forming an

intransitive verbal stem from a nominal or pronominal form, as in (15).

(15) malas ngay-gingge-:la (Middle Clarence dialects)

THAT 1SG-INCHOATIVE-PRESENT

'He looks like me.' (Crowley 1978:91)

This variant treatment could reflect a dialectal difference, or just a difference of

analysis on the part of the Geytenbeeks and of Crowley.

A derivational suffix must, of course, immediately follow the form it is

attached to (corresponding to the CC in a copula clause). And a copula verb will

often immediately follow the CC. In sentences such as (13)-(15), either the

copula verb analysis or the inchoative derivational suffix analysis would be

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

20 ANTHROPOLOGICAL

LINGUISTICS 44 NO. 1

plausible. To definitively determine whether kana is a verb or a suffix in (13)

and whether gingge is an affix or a suffix in (14)-(15),the linguist would have to

explore whether alternative orderings are possible. For instance, if one could

detach gingge-:la from ngay in (15)--saying ngay mala gingge-:la or mala

gingge-:la ngay, etc., with the same meaning--then ginggi- must be analyzed as

a copula; if not, it is a derivational suffix.9

Geytenbeek and Geytenbeek(1971:14,43-44) recognize a further inchoative

verb wana-'be'. However, Sharpe, in her dictionaryof the Western Bandjalang

dialect, has wana- 'to be, become' implicitly analyzed as an an affix, which

"follows adjective, etc. it verbalises" (1995:95). And Smythe (1978:322, 453) in

his grammarof an eastern variety of Bandjalanghas -wan-a 'become,be' as an

"intransitive enclitic verb base," as in djangwana 'become bad'. In all the ex-

amples quoted by the Geytenbeeks, wana- follows directly after the CC, making

an affixal interpretation possible here. For both ginggi- and wana- in Ban-

djalang, we cannot tell whether dialectal differences are involved, or varying

analytic decisions by different linguists. However, for other languages there is

available data on variant ordering possibilities, so that a decision between

copula and affixalinterpretationof forms 'become'can be made with confidence.

In many Australian languages, the concept of 'becoming' is coded through

an inchoative suffix; for instance, 'be good!' is rendered by 'good-INCHOATIVE-

IMPERATIVE!' Evans (1995:322) reports an interesting contrast in Kayardild;

here, 'becomeX' is expressedwith the inchoativesuffix -wa-tha if X is a nominal

word, but with the copulaverb wirdijaif X is an NP (since the suffix only applies

to lexemes, not to NPs).

In Gurindji, 'become' is expressed by the copula verb 'be' plus a special

'becoming'suffix on the CC (whichis an adjectivein the examples quoted). Com-

pare the sense 'be' in (16a) with 'become'in (16b).

(16a) kunjinics winkiljingcckarri-njana (Gurindji)

coals red be-present

'Thecoalsare(happento be at the moment)red.' (McConvell

1990:82)

(16b) partawan-pijikcckarr-u ngamanjcs (Gurindji)

hard-become be-future fontanelle

'Thefontanellewill get hard.' (McConvell

1990:82)

Copulas typically develop out of a stance or motion verb (e.g., 'sit', 'stand',

'lie', 'go');see table 6 and discussion in section 3.4. We also find examples of an

inchoative suffix being created by grammaticalization of a stance or motion

verb. For example, in WHc4 in map 1, Yinjtjiparnrti (a language with no

apparent copula), one inchoative suffix has the form -karri, homonymous with

the verb karri-'stand' (Wordick 1982:88). The path of grammaticalization is

likely to be: lexical verb 'stand' > copula verb 'become' > inchoative verbal

derivational suffix 'become'.

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 R M.W.DIXON 21

3.4. Copulas and verbs of rest and motion. In a numberof Australian

languages, each of the three main stance (or postural) verbs can be used to refer

to the existence of something.'0Typically'stand' is used of a vertically extended

object, 'lie' of a horizontallyextended object, and 'sit' if there is neither vertical

nor horizontal extension. Arabanabehaves like this, as shown in (17).

(17) Marni-nga [patharra parkulu]s tharka-rnda (Arabana)

box.tree two

place-LOCATIVE stand-present

'Therearetwo box-treesat Marni.'(lit., 'Twobox-treesare standingat Marni.')

(Hercus 1994:294)

This is an intransitive clause with an intransitive verb (tharka-'stand, exist in

a standing posture'),a core argument in S function, and an oblique argument in

locative function.

In some languages, one of the stance verbs also functions as a copula. This

can be recognizedfrom both its syntax and its meaning. That is, it now has two

core arguments,in CS and CC function,and it no longerhas referentialmeaning

to a type of stance, but simply a relational meaning. In Arabana it is the verb

thangka- 'sit' which may also be used as a copula, as in (18). It is then "neutral

as to stance, and the notion 'to sit' has totally faded"(Hercus 1994:295).

(18) anthacs minpaRucc thangka-ka (Arabana)

1SG doctor be-PAST

'I was a [tribal]doctor(butI havenowlostmy specialpowers).'(Hercus1994:295)

Note that the copula thangka- is only included"whentense has to be expressed"

(Hercus 1994:295).Thus a statement 'I am a doctor'will be just antha minpaRu,

with no copulaverb included.

McGregor(1990:310-11) discusses the three stance verbs in Gooniyandiand

then states "ofthe three verbs, bagi- 'lie' appears to be the least marked one

semantically, and is used when the entity adopts no particular posture, and is

completely inactive in an abstract situation of being"(1990:310). He exemplifies

with (19).

(19) jirigics yingi-ngaddic bagiri (Gooniyandi)

bird name-COMITATIVEit+be+PRESENT

'The birds [all] have names.' (lit., 'Thebirds are [all] with names.') (McGregor1990:

311)

For the Western Desert language, Eckert and Hudson (1988:50-51) discuss

and exemplify four stance verbs ('sit', 'lie', 'crouch', and 'stand') and then

comment "in situations where none of the posture verbs apply ngara-...

'standing' is used" (1988:51). Their illustrations include (20).

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

22 ANTHROPOLOGICAL

LINGUISTICS 44 NO. 1

(20) ngayulucs [pika purlka mulapa]oc ngara-ngi (Western Desert language)

1SG sick very truly be-PAST

'I was reallyverysick.' (EckertandHudson1988:51)

In all of these languages each of the stance verbs can be used in an existen-

tial sense, but is then functioning as an intransitive verb (with one core argu-

ment, in S function).In each language there is just one stance verb that can also

function as a copula verb, with two core arguments (in CS and CC functions),

and with a relational rather than a referential meaning. This is 'sit' in Arabana

(and in Yir-Yoront,Waga-Waga,Pitta-Pitta, Yandruwanhdha,Nyungar, Mar-

tuthunira, Panyjima, Warlpiri,Arrernte, Wardaman, and Wambaya); 'lie' in

Gooniyandi (and in Guugu Yimidhirr and Wardaman);'lie on one's back' in

Gidabal; and 'stand' in Wiranguand the Western Desert language.

We also find instances of a copula verb in one languagebeing cognate with a

stance verb in another language. This applies to karri-'be' in Gurindji and to

wara- 'be, become' in Biri and Gidabal (both cognate with 'stand' in nearby

languages'1) and to wiyi-'be' in Bidjara and Gunja (cognatewith 'sit' in nearby

languages, including Ngiyambaa).

The literature includesone illustrationof the process of evolution of a stance

verb to also have copula meaning. Haviland (1979:117-18) reports that just

younger speakers of Guugu Yimidhirruse wu-'lie, exist' also as a copula, where

there is no sense of 'lying', as in (21).

(21) gana-aygu ngayucs yinil4c wu-nay (Guugu Yimidhirr)

1SG

before-EMPHATIC frightened be-PAST

'Before,I usedto befrightened.'(Haviland1979:117)

However, Haviland reportsbriefly that "olderspeakers criticizeyounger speak-

ers for indiscriminatelyusing wu-... as a tense-carryingdummyverb, when the

subjects ... involved do not actually lie but rather stand or sit" (1979:118). This

is likely to indicate that wu- 'lie' has developed a second, copula sense within

the lifetimes of the oldest speakers, so that they decry this new development.

There is another intransitive verb which has developed a further, copula,

sense in a number of Australian languages; this is the motion verb 'go'. In

Martuthunira, both the stance verb njina- 'sit, stay' and also the motion verb

puni- 'go' are also now used as copulas. Dench states that the copula use of

puni- "doesnot imply any motion on the part of the subject";he then adds: "the

use of the puni- ... copula (rather than njina- .. .) indicates that the ascribed

state will be maintained while other actions are performed"(1995:213).There is

plainly a connection between the idea of a continuously maintained relation (in

the copula use of puni-) and the idea of'going' (which must be maintained for a

period of time); and between the copula use of njina- to simply refer to a

relation, and the use of njina- as an intransitive verb 'sit, be sitting' which

simply describes a state.

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 R M. W. DIXON 23

The copula verb -yi- 'become'in Gaagudju is homonymous with the intran-

sitive verb 'go'. We can see a connection between the idea of change of state

involved in 'becoming' and that of change of position inherent in 'going'. Other

languages in table 6 with the form 'go' also functioning as a copula are Gum-

baynggirr (illustrated in (11) above), Warray,Gaagudju,and Kamu. (Note that

Warray and Kamu, although probablynot closely genetically related, are con-

tiguous languages, with Gaagudjubeing a little way off within the same area.

This is the only instance in Australia of there being a shared regional basis for

which a verb of rest or motion comes to be grammaticalized as a copula.)

In other languages, verbs with different meanings have also developed a

copula sense--intransitive verbs with meanings such as 'stay', 'remain', 'live',

and 'dwell' in Njangumarta, Walmatjarri,Gurindji,Lardil, and Kayardild;the

transitive verb 'leave' in Gidabal; and in Yandruwanhdha a verb that can be

used intransitively with meaning 'do' and transitively with meaning 'tell'.

3.5. The relation of location. In most Australian languages, statement of

location involves an intransitive verb used in an existential sense, plus an NP

with local case marking, as in (17). It appears that in some languages with a

copula verb (especially those in which the same form doubles as a stance verb)

statements of location involve an intransitive verb rather than the copula.

However, there are some languages with a well-defined copula--used in the

identity/equation relation, (a)-where the copula also covers the local relation,

(c). This occurs,for example, in Muruwarri,as in (22).

(22) tirra-ngkacc yi-n-thirri-pu? (Muruwarri)

where-LOCATIVEbe-REALIS-PRESENT-3SG.CS

'Where is he?' (Oates 1988:122)

It is useful to distinguish two varieties of local NP: (i) those consisting of a

shifter or interrogative,such as 'here','there', 'where'; and (ii) those whose head

is a noun. It seems that in some languages copulas are used for a local relation

involving (i) or (ii), whereas in others they are restricted to (i).

For Ngiyambaa, Donaldson(1980:233)states that a copulais acceptablein a

but if the CC includes

sentence such as (23a), where the CC is 'HERE+LOCATIVE',

a noun as head, then an appropriatestance verb ('sit', 'stand', or 'lie') must be

used in place of the copula, as in (23b).

(23a) bura:ycs nginicc ga-ra (Ngiyambaa)

child HERE+LOCATIVE be-PRESENT

'There are children here.' (lit., 'Childrenare here.') (Donaldson 1980:233)

(23b) bura:ys galing-gaoBLQUEwara-nha (Ngiyambaa)

child water-LOCATIVE stand-PRESENT

'There are children standing by the water.' (lit., 'Children are standing by the

water.') (Donaldson 1980:233)

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

24 ANTHROPOLOGICAL

LINGUISTICS 44 NO. 1

For a number of languages, all the examples quoted in the source materials

of a copula in locativerelation are of type (i), involving 'here', 'there', or 'where'.

(It may be that for some of these languages the copula can also occur with a

locational NP of type (ii), it is just that no such examples have been provided.)

These languages have a plus sign in parentheses, (+), in column (c) of table 6.

For other languages, the source materials include examples of a copula

being used for local relations of both type (i) and type (ii); these receive a plain

plus sign, +, in column (c) of table 6. In the first grammar ever written of an

Australian language, Threlkeld (1834:105-30) provides instances of the copula

verb ga- in Awabagal being used for identity/equation, for attribution, and for

both kinds of local relation; an example is (24) (in which Threlkeld's spelling is

retained).

(24) kabo kunnun (Awabagal)

by.and.by bangcs

1SG be+FUTURESydney-kacc

place-LOCATIVE

'By-and-byI shallbe at Sydney.'(Threlkeld1834:113)

In Biri, there is an example of a copula verb taking a CC which involves local

case marking with a metaphorical sense, shown here in (25).

(25) [ngaya guli]cs wara-ng-aya yalu-nggacc (Biri)

1SG angry be-PRESENT-lSG.CS child-LDCATIVE

'I'mangryat the child.'(lit.,'Myangri[ness]is at the child.')(Beale1974:11)

3.6. Other relations. In some languages, a clearly established copula verb

may also be used to express a relation of possession, (d), or wanting/benefac-

tion, (e).

The possessive relation can be illustrated for Ngiyambaa (here = indicates

an enclitic which is attached to the first word of the clause):

(26) wanga:y=dji:cc bura:ycs ga-ra (Ngiyambaa)

child

NEGATIVE=1SG+POSSESSIVE be-PRESENT

'I haveno children.'(lit., 'Childis notofme.') (Donaldson1980:129)

There are further examples of the possession relation in Muruwarri (Oates

1988:281) and in Arrernte (Wilkins 1989:438).12

Relation (e), wanting/benefaction, is typicallymarked by dative case on the

CC, as in (27), from Biri.

(27) ngayacs manhdha-gucc wara-ng-aya (Biri)

1SG food-DATIVE be-PRESENT-1SG.CS

'I want food.' (lit., 'I am for food.') (Beale 1974:9)

There are further examples of relation (e) in Gidabal (Geytenbeek and Geyten-

beek 1971:44) and Gurindji (McConvell 1990:83). As a variant on this relation,

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 R. M. W. DIXON 25

in Ngiyambaa the CC can be a complement clause, e.g., 'Ics [meat eat-

PURPOSIVE]cc be' for 'I want to eat meat' (Donaldson 1980:281).

As mentioned in section 3.4, in most Australian languages existence is

shown by a stance verb; that is, the appropriate stance must be specified.

However, there are languages in which a copula verb may also have monovalent

use, indicating (f) existence. For example, in Biri we have sentences such as (28).

(28) gamuc wara-na (Biri)

water be-IMPERFECTIVE

'It is raining.' (lit., 'Wateris.') (Holmer 1983:370)

This construction also exists in Martuthunira, as in (29), where kuwarri 'now' is

an adverbal modifier (not a copula complement).

(29) nhunhaac njina-nguru kuwarri (Martuthunira)

THAT be-PRESENTnow

'That one exists today.' (lit., 'That one is now.') (Dench 1995:210)

Existential senses of a copula verb are also included in data from Ngiyambaa

(Donaldson 1980:226), Muruwarri (Oates 1988:197), the Western Desert lan-

guage (Goddard 1985:39), Walmatjarri (Hudson 1978:94-95), and Wardaman

(Merlan 1994:213).

As in languages from other parts of the world (including English), the

form used as a copula verb may have additional grammatical functions. For

example, in Yuwaalaraay 'be' can also be used with another verb in future tense

to express a progressive meaning (Williams 1980:69).

3.7. Form. In section 2.2, I pointed out that copula verbs typically show either

more or fewer TAM or other inflectional categories than other verbs, and that

they typically have irregular paradigms.

In some Australian languages a copula verb does have irregular forms. It is

reported that gi- 'become' is the only irregular verb in Yuwaalaraay (Williams

1980:68); and similarly for ye- 'be, become' in the Duungidjawu dialect of Waga-

Waga (Kite 2000:105). In Gidabal, wana-'be' and wara-'be become' are among

the fourteen irregular verbs (Geytenbeek and Geytenbeek 1971:26-27), and in

Ngiyambaa ga- 'be' has an irregular past form, giyi (Donaldson 1980:158). For

Warray, Harvey (1986:159) mentions three irregular verbs; one of them is

-yang-, which is both an intransitive verb 'go' and a copula verb 'be'.

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

bDb

r,-.I

a B M

a b

d

E

lijl 0

P

a

A2

0 HJ e

a R_

8'

t I

e

Al c V

d

El K d

NA

%I.

0 b

a

U ,b

X WB

r WMb

m N@ WK

gg

cm 500km

0m

Mixl

~

rNC

NDO (shaded).

0

NG

0 WE

verb

copula

a

cj ~aa

LlY

d b WI with

r " (2002).

.

I a !.C' rm WH Nam%

B

9g WG

44(1):26

NK La i

languages

4k h

I

cS J

d IL b Linguistics

1 h

,

NL

3% Australian

d.caA

r 1.

-

I N bt

d

Map Anthropological

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 R M.W.DIXON 27

There is only one report of a copula verb in an Australian language having

limited TAM possibilities. Merlan (1994:213) states that Wardaman -yu- 'be'

has a defective paradigm; it only occurs in present tense and nonpast sub-

ordinate, forms of the other copula,-jingi-, being used elsewhere. Hercus (1986:

47) mentions that in the data she recorded from the last speakers of Wemba-

Wemba, the copula yuma- 'be' only takes third-person bound pronominal suf-

fixes (never first- or second-personsuffixes, even when the CS is first or second

person).

3.8. Distribution. In table 6 and map 1, each language is assigned a code

(given in the first column), accordingto the system followed in Dixon (2002).

This involves dividing the approximately 250 languages of Australia into fifty

groups, labeled A-Y,WA-WMand NA-NL. Some of the groups are putative low-

level genetic groups, some constitute small linguistic areas (within the large

linguistic area that encompasses all of Australia), and some groups consist of

languages put together simply on a geographicalbasis. A number of groups are

subdivided; thus, groupJ consists of Ja, Jb, Jc, Jd and Je.

The distribution of languages with a copula verb, as summarized in table

6, shown by shading on map 1. It will be seen that the shading covers a good

is

deal of Australia, involving a number of continuous areas and also some isolated

regions.

However, the reader should be cautioned against inferring too much from

map 1. For some languages we have very limited materials-sometimes just one

or two short word lists, other times a short grammar with just a couple of

nominal and verbal paradigms.A number of grammars written in recent times

have relied upon informationfrom semispeakers and are far from complete. In

every language in which it occurs, the copula clause is a minor clause type, so

that some grammars which are of a fairly good standard overall may have

omitted to note it. For example, Smythe (1948-49:71) discusses the copula verb

yana- in Gumbaynggirr,but this was not noted by Eades (1979) in her grammar

of the same language. The point being made is that just because a copula clause

has not been reportedfor a given language does not mean that it does not (or did

not) exist in that language.

The information available is slim for groups Jb-e, K, L, Mb-e, Nb, Ne, O-S,

U, WAc-d,WB, and WE, among others. Some of these languages may well have

had copula clauses and should thus be shaded, joining up some of the shaded

areas on map 1. We just do not know (and, for most of these languages, we are

never likely to know).

Some of the earliest and most influential modern Australian grammars

were of languages in which there is no copula verb, e.g., W1, Kalkatungu (Blake

1969, 1979a); H1, Dyirbal (Dixon 1972); and G2, Yidinj (Dixon 1977). There has

been no systematic study of copulas in Australian languages, and no guidelines

have been published on the properties a verb should show for it to be considered

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

28 LINGUISTICS

ANTHROPOLoGICAL 44 NO.1

a copula. When we put together (i) the partial data on some languages; (ii) the

marginal nature of copula clause constructionsin those languages in which they

do occur; (iii) the fact that a copula verb may be homonymouswith an intransi-

tive verb of stance or motion; and (iv) the lack of any tradition of, or guidelines

for, describing copula clause constructions in Australian languages, these four

factors combine to provide only a partial picture of the overall situation. There

certainly are some languages lacking copulas-as just mentioned, they include

Kalkatungu, Dyirbal and Yidinj-but it is likely that copulas occur (or occurred)

in a number of languages that are not shaded on map 1.

What is significant is the wide areas over which copula clauses occur, as

shown in map 1, and the fact that each language with one or more copula verbs

appears to have developedthese in its own way, differentlyfrom its genetic rela-

tives and geographicalneighbors. For instance, within the Ja genetic subgroup,

Biri has copula verb wara- (cognate with 'stand' in nearby languages), while

Bidjara/Gunja has wiyi- (cognate with 'sit' in nearby languages) and barda-

(cognates as yet untraced). Similar differences between languages that are

closely genetically related are found in subgroupsTa, WJ and NA (see table 6).

In Dixon (1997, 2002) the idea is promulgated that the languages of Aus-

tralia comprise a large linguistic area, an equilibrium situation that has con-

siderable time depth. There has typically been diffusion across the continent,

sometimes of grammatical forms but much more often of structural patterns.

For example, the property of having switch-referencemarking, or of having a

system of noun classes, may diffuse from language to language across a con-

tinuous area. It is just the grammaticalpropertythat is borrowed,not the forms

employed to express it (see Austin 1981b;Dixon 2002:470-508, 527-29). That is,

a language which adopts switch-reference or noun classes from its neighbors

will develop its own formal marking for the new system, from its own internal

resources.

Because of the continual processes of diffusion, the languages of Australia

have for millennia, or perhaps for tens of millennia, been converging in their

structural profiles. This leads to recurrent tendencies towards new develop-

ments. It appears that Australian languages share a tendency to develop copula

verbs, typically by grammaticalizing a verb of rest or motion. But it may be a

different verb in two related, or contiguous, languages, and even if the verbs

have similar meaning, the forms may be different (comparenguna- 'stay, be' in

WJal, Walmatjari, and karri- 'stay, be' in the closely genetically related lan-

guage WJa3, Gurindji,for example).

The creation of a copulaverb may happen spontaneouslyin a language, with

copulas not being found in any neighbors. This appears to apply to Ddl, Guugu

Yimidhirr, and to Ebl, Yir-Yoront(although it must be pointed out that we do

not have full grammatical information on all the neighbors for each of these

languages). But it is also clear that, once a copula verb is created, then the pro-

perty of having a copula verb is likely to diffuse to neighboring languages, over

This content downloaded on Tue, 8 Jan 2013 09:09:58 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

2002 RM. W. DIXON 29

an increasingly wide area; see the shading on map 1. That is, we have here an

additionalexampleof a diffusionarea, to add to the many diffusionareas deline-

ated in Dixon (2002). If a language has a copula verb then neighboring lan-

guages may develop one or more copulas,but they will do this from within their

own resources, in a different way for each language. It is just the grammatical

category of "copulaclause type" that is borrowed,not the copula verb itself.

4. Summary and conclusion. I first presented a typologicalcharacterization