Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fcomm 07 765336

Uploaded by

Kathryn LusicaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fcomm 07 765336

Uploaded by

Kathryn LusicaCopyright:

Available Formats

BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT

published: 16 February 2022

doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.765336

Planning for a Crisis, but Preparing

for Every Day: What Predicts

Schools’ Preparedness to Respond

to a School Safety Crisis?

Catherine P. Bradshaw 1,2*, Katrina J. Debnam 1,2 , Joseph M. Kush 1 and

Sarah Lindstrom Johnson 3

1

School of Education and Human Development, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, United States, 2 Johns Hopkins

Center for the Prevention of Youth Violence, Baltimore, MD, United States, 3 The Sanford School, Arizona State University,

Tempe, AZ, United States

This study aimed to identify potential gaps related to crisis preparedness at 98 public

secondary schools. We focused on crises that may occur following a substantiated

eminent threat of school violence. Crisis preparedness data collected by trained external

assessors captured knowledge of the procedure for responding in a safety-related crisis

and process for notifying school staff, as well as the posting of the crisis plan in school

Edited by: locations. Data were analyzed in conjunction with data on student- and staff-reported

Darren C. Treadway, school climate, school demographics, and external observations of the school. Analyses

Niagara University, United States

indicated that the staff were least aware of the process for notifying staff that a crisis

Reviewed by:

John James Kiefer, was occurring. Middle schools, schools with higher levels of school disorder, and those

University of New Orleans, with poorer reading and math scores were less likely to know the procedure, know the

United States

notification process, and have the plans posted in all locations. Schools also need to

Andreia de Bem Machado,

Federal University of Santa improve posting of school crisis procedures in shared and open spaces, such as the

Catarina, Brazil cafeteria and gymnasium; this is especially critical given that many school shootings

*Correspondence: occur in these large open spaces. Multilevel analyses indicated that staff perceptions

Catherine P. Bradshaw

cpb8g@virginia.edu of safety were significantly higher in schools in which the procedure was posted in all

locations. Together, these findings provide evidence of a link among crisis planning,

Specialty section: school context, and school climate, and complement the need for additional training

This article was submitted to

Organizational Psychology,

on what to do following the substantiation of a credible and eminent threat.

a section of the journal

Keywords: school safety, school climate, crisis planning, prevention, threat assessment, school processes

Frontiers in Communication

Received: 02 September 2021

Accepted: 17 January 2022 INTRODUCTION

Published: 16 February 2022

Citation: Many researchers, families, practitioners, educators, and policy makers have expressed increased

Bradshaw CP, Debnam KJ, Kush JM concerns regarding school safety in response to the recent increase in school shootings (Federal

and Lindstrom Johnson S (2022) Bureau of Investigation, n.d). Federal efforts, such as Now Is the Time initiative (White House,

Planning for a Crisis, But Preparing for

2013), noted that it is “essential that schools have in place effective and reliable plans to respond”

Every Day: What Predicts Schools’

Preparedness to Respond to a School

to school shootings and other types of violence-related emergencies. In response to the recent

Safety Crisis? uptick in school shootings, multiple researchers, professional organizations (Flannery et al., 2019),

Front. Commun. 7:765336. and policymakers (US Department of Education, 2018) also have highlighted the significance of

doi: 10.3389/fcomm.2022.765336 school safety and crisis planning and prevention. Specifically, a “crisis is a situation where schools

Frontiers in Communication | www.frontiersin.org 1 February 2022 | Volume 7 | Article 765336

Bradshaw et al. School Crisis Preparedness

could be faced with inadequate information, not enough TABLE 1 | School-level demographics and correlations between school-level and

time, and insufficient resources, but in which leaders must the three crisis indicators.

make one or many crucial decisions” (US Department of School-level variables Means (SD) Notification Location Procedure

Education Office of Safe Drug-Free Schools, 2003). As such,

crisis planning and management should include processes for High school (vs. Middle) 0.59 (0.49) 0.043 0.053 0.300**

mitigation/prevention, preparedness, response, and recovery. As Enrollment 1077.4 (427.34) −0.001 −0.075 0.066

a result, the recommended approaches for responding to specific Minority students (%) 56.70 (25.75) −0.134 −0.031 −0.134

types of crisis varies and change based on emerging evidence. Attendance (%) 93.94 (1.37) 0.165 0.085 0.046

For example, best practices in the field related to safety-crisis FARMs (%) 40.53 (17.53) 0.041 −0.059 −0.160

have shifted in recent years from more traditional “lockdown” Mobility (%) 18.14 (15.74) −0.100 −0.066 0.014

approaches focused on securing persons in classrooms, to a Suspension (%) 13.83 (10.80) −0.088 −0.099 −0.190

more “active response,” which includes running, hiding, and in AppearanceSAfETy 6.60 (1.15) −0.116 0.012 −0.098

some instances approaching the shooter. Given these changes, DisorderSAfETy 3.28 (1.56) −0.169 −0.238* −0.108

the seriousness of these issues, and the required involvement of SurveillanceSAfETy 9.35 (4.55) −0.004 −0.176 −0.006

school staff, it is imperative that we explore school staff members

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. School type: was coded 0 = middle school, 1 = high school. FARMs

understanding of their schools’ safety-related crisis plan.

= percentage of students qualifying for free and reduced price meals. The Appearance,

The increased attention to school safety issues, including the Disorder, and Surveillance variables represent mean observed composite scale score on

use of prevention programming, enhanced security measures, the SAfETy.

and crisis assessment procedures is critical for advancing the field

(Flannery et al., 2019), and potentially helpful for school staff who

are often on the front lines of a safety crisis. Yet there is a limited professional development of school staff and school leaders to

research on the critical elements of school crisis preparedness in turn reduce response times, confusion, and potentially life-

(US Department of Education Office of Safe Drug-Free Schools, threating errors when faced with a school safety crisis. This may

2003). In fact, there is some concern that an excessive focus be a needed component of threat assessment training for schools.

on school safety measures may actually make students and staff

feel less safe, as it may contribute to a sense of vulnerability,

anxiety, and hypervigilance (Lindstrom Johnson et al., 2018). MATERIALS AND METHODS

Nevertheless, such responses to a school safety crisis, whether

personally experienced or exposed to in the media, can heighten Data were collected from 98 public schools (40 middle and

attention to issues of safety and motivate schools to develop 58 high) in a mid-Atlantic state. The schools spanned rural,

and provide training on a plan for managing such situations. suburban, and urban fringe contexts and served a diverse student

Actually having a crisis plan is just one aspect of the process, body. See Table 1 for school demographics.

communicating the plan and having staff members remember,

procedurally, what to do for all students in these instances Instruments and Procedures

is equally important. Threat assessment aims to systematize An external evaluator following a formal training protocol and

response to potential threats and thus awareness of the process is reliability assessment (see Debnam et al., 2012) scheduled a

a critical component. This may also relate to ensuring appropriate one-day visit to each school to administer the School-wide

communication upon disclosure of threats as often threats are Evaluation Tool (SET; Sugai et al., 2001). SET data were collected

communicated with members of the school staff not on the threat using a written protocol, which includes brief interviews with

assessment team (Cornell, 2020). administrators and 12 randomly-selected school staff members, a

The overarching goal of this study was to identify potential tour of the school, and a review of materials (e.g., posted signage,

gaps related to school crisis preparation, with a particular focus written plans and protocols, training plans). Specifically, the SET

on (1) knowledge of the procedure for responding in a crisis, assessed whether school staff agreed with the administration on

(2) process for notifying school staff, and (3) the posting of how staff will be notified (e.g., code word, how they would be

the crisis plan in specific school locations. We leveraged data notified of a safety emergency) of a safety crisis (e.g., stranger in

collected from outside assessors from middle and high schools to building with a weapon) and the procedures for responding to a

identify potential gaps in these three areas of crisis preparedness. crisis. In addition, the evaluator recorded the posting of the crisis

We focused specifically on secondary schools, as the rates of plan across seven pre-determined school locations (e.g., hallways,

school crisis and discipline problems are higher at this grade level cafeteria, classroom) during the assessment.

compared to elementary schools (US Department of Education, School climate data came from the Maryland Safe and

2018). We then explored the extent to which these three aspects Supportive Schools Climate Survey (MDS3; Bradshaw et al., 2014),

of preparedness varied as a function of perceptions of school which was administered anonymously to students and staff at

climate, school characteristics, and external ratings of the school each school to assess perceptions of safety, engagement, and

environment, as these analyses may help identify schools in environment. Student- and staff-report scales were adapted from

greatest need of professional development and training related previously developed measures and have demonstrated strong

to crisis preparedness. Having an enhanced understanding of the psychometric properties (Bradshaw et al., 2014). This measure

gaps in school safety and crisis responses may inform further has robust psychometric properties, and has demonstrated strong

Frontiers in Communication | www.frontiersin.org 2 February 2022 | Volume 7 | Article 765336

Bradshaw et al. School Crisis Preparedness

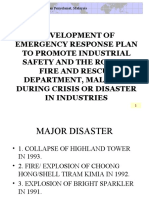

FIGURE 1 | Percentage of locations where crisis plan was observed to be posted by the study assessor. Classrooms 1, 2, and 3 were randomly selected classrooms

reviewed by assessor, balancing across different grade levels within the school.

measurement invariance across middle and high schools (see The correlation analyses indicated that high schools were

Waasdorp et al., 2019). more likely to know the procedure for how to respond, and that

The School Assessment for Environmental Typology (SAfETy; higher disorder was associated with fewer locations where the

Bradshaw et al., 2015) was administered by a second set of trained procedure was posted (Table 1). Regression analyses (Table 2),

external assessors who rated the presence/absence of various which included a number of school-level covariates, further

indicators across multiple school locations (e.g., alcohol bottles in suggested that schools with a higher level of disorder, based

playing fields, drug paraphernalia in playing fields, broken lights on external observer ratings, were less clear on the notification

in hallways) to create Disorder, Surveillance, and Appearance process, procedure for responding, and had fewer locations

scales (Lindstrom Johnson et al., 2018). For additional data and where the procedures were posted. Similarly, both higher

information on the reliability and training for the SAfETy, see suspensions and being a middle school were associated with

Bradshaw et al. (2015). being less likely to know the procedure to respond, whereas

School demographic data (e.g., suspensions, enrollment, higher attendance rate was associated with greater knowledge

attendance, free or reduced meals rate [FARMS]) were retrieved of the notification process. Finally, the multilevel analyses (not

from the State Department of Education. tabled) indicated that student perceptions of safety were inversely

associated with suspension rates (βstudent = −0.010, p = 0.020),

but positively associated with attendance rates (βstudent = 0.325,

RESULTS p = 0.002). Moreover, staff perceptions of safety were positively

related to the number of locations in which the procedure was

The biggest inconsistencies were in regard to the process posted (βstaff = 0.487, p = 0.008); however, neither student- nor

for notifying staff that a crisis was occurring. Specifically, in staff-reported safety was related to knowing the procedure or the

approximately half of the schools (55.1%), all of the staff who notification process.

were interviewed were aware of how they would be notified,

whereas a quarter of the schools had <80% staff aware of how

they would be notified. When it came to knowing what to do DISCUSSION

(i.e., procedure), ∼77.6% of schools had all staff who were aware

of the procedure, whereas 7.15% of the schools had <90% of The overarching goal of this study was to identify gaps in

staff who knew the procedure. With regard to the posting of the crisis planning and response in secondary schools. In exploring

procedure in the 7 specified locations, 70.4% of the schools had this issue, we drew upon multiple sources of data, collected

the procedure posted in all locations; whereas 12.2% had the plan from external assessors, outside observations, students, staff,

posted in 5 or fewer locations; the cafeteria (13.3% not posted) and administrative records. Together, the data suggested that

and non-classroom activity space (i.e., gym, computer lab; 13.3%) although there was generally a high level of awareness of crisis

were the locations where the plan was the least likely to be posted procedures and consistent posting of the procedure, there was

(see Figure 1). greater inconsistency in the notification process (e.g., code word,

Frontiers in Communication | www.frontiersin.org 3 February 2022 | Volume 7 | Article 765336

Bradshaw et al. School Crisis Preparedness

TABLE 2 | Logistic regression analyses for school-level demographics and the mean SAfETy scores for the three crisis indicators.

Notification Location Procedure

Predictor variables Coefficient S.E. Odds ratio Coefficient S.E. Odds ratio Coefficient S.E. Odds ratio

Intercept −63.992 28.049 0.000* −7.537 26.499 0.001 −47.319 39.117 0.000

High school (vs. Middle) 0.691 0.653 1.995 1.027 0.732 2.794 4.106 1.285 60.690*

Enrollment 0.001 0.001 1.001 0.000 0.001 1.000 −0.001 0.001 0.999

Minority students (%) −0.027 0.014 0.973* 0.003 0.015 1.003 0.004 0.023 1.004

Attendance (%) 0.694 0.286 2.001* 0.108 0.269 1.114 0.563 0.404 1.757

FARMs (%) 0.062 0.026 1.064* −0.001 0.027 0.975 −0.005 0.034 0.995

Mobility (%) 0.001 0.019 1.001 0.005 0.019 1.005 0.089 0.080 1.093

Suspension (%) −0.024 0.026 0.976 −0.027 0.026 0.974 −0.096 0.039 0.909*

AppearanceSAfETy −0.344 0.248 0.709 −0.037 0.259 0.963 −0.539 0.401 0.584

DisorderSAfETy −0.438 0.196 0.646* −0.432 0.206 0.649* −0.754 0.316 0.471*

SurveillanceSAfETy 0.031 0.060 1.036 −0.064 0.064 0.938 0.099 0.093 1.104

*p < 0.05. School type was coded 0 = middle school, 1 = high school. FARMs = percentage of students qualifying for free and reduced price meals. The Appearance, Disorder, and

Surveillance variables represent mean observed composite scale scores on the SAfETy.

how they would be notified). High schools also appeared to 2009). These gaps appear to be particularly salient for middle

be better prepared when it came to having awareness of the schools and those schools with higher disorder, as indicated by

procedure for managing a crisis, suggesting that additional elevated suspensions, external observations of disorder, and low

training is needed in middle schools. In addition, schools also attendance. This is important as research suggests the importance

need to improve posting of school crisis procedures in shared of dynamic and situational factors as precursors for violence

and open spaces, such as the cafeteria and gymnasium; this is (Cornell, 2020).

especially critical given that many school shootings occur in these There are a number of important implications of these

large open spaces (US Department of Education, 2018). findings. For example, members of threat assessment teams

Although the associations examined were cross-sectional and can play an important role in this process by providing

causality cannot be inferred, school staff also felt safer in schools consultation, training, and ongoing monitoring of the staff

where the procedure for managing a crisis was posted in more members’ knowledge of the procedures to use in a school safety

locations across the school. The results more generally suggested crisis. It is also important to conceptualize this issue as a public

a link between school climate and crisis planning, whereby health concern (Flannery et al., 2019), and accordingly help

more disordered schools may be less likely to be prepared schools receive training and support across all three levels of

for responding in a crisis. These findings are consistent with preventive intervention. More specifically, crisis preparedness is

prior studies and the recent report of the Federal Commission considered a secondary intervention which outlines the steps to

on School Safety (US Department of Education, 2018) which be taken in the event of a crisis. As such, it is a critical element

have concluded that school climate is critical to preventing of a school safety plan. But also important are primary prevention

school violence (Flannery et al., 2019). Moreover, school staff activities, such as positive behavior interventions and supports

need training to enhance preparedness, and to reduce gaps (Bradshaw et al., 2012) and social-emotional learning programs

between what is intended by the administration and what are (Bradshaw, 2015); these research-based models are also needed

known procedures by school staff in a crisis. Research has to provide universal supports to all students on an everyday

emphasized the importance of consistent training for high quality basis to help prevent problems before they occur. Moreover,

implementation of the core features of evidence-based threat these prevention approaches can also improve school climate

assessment models (see, for example, Cornell et al., 2017). (i.e., safety and disorder; Bradshaw et al., 2014), which was shown

Taken together, these findings provide rather compelling in the current study to be associated with better preparedness for

evidence of the importance of providing ongoing training, a crisis. In addition, tertiary intervention, which involves long-

especially regarding the notification process. Additional training term, follow-up mental health supports to victims of a crisis is a

is needed to ensure that staff are aware that a crisis is occurring, critical support system following an event.

in order to trigger a rapid response. This is particularly important These findings highlight the importance of ongoing training

during threat assessment so that the notification can begin the for all school staff in crisis planning to ensure a timely and

process of evaluating if there is a threat. Regular review of accurate response. This training needs to be extended beyond

procedures and the notification process is needed to ensure that select members of the school, such as the threat assessment

staff, and in turn students, are prepared to respond efficiently team, to the broader school staff in order to ensure the

and appropriately in a crisis situation. These findings extend goals of preventing a safety-crisis are met (Cornell, 2020).

previous studies by highlighting the importance of regular In addition, crisis management and planning needs to be

training for both students and staff on crisis procedures as situated within tiered prevention models in order to both

being critical to enhancing school preparedness (Ramirez et al., prevent and identify a broad range of threats to school safety

Frontiers in Communication | www.frontiersin.org 4 February 2022 | Volume 7 | Article 765336

Bradshaw et al. School Crisis Preparedness

(Flannery et al., 2019). Together these interventions allow AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

schools to not just be prepared for a crisis, but improve the

school environment and allow for students to fully participate CB conceptualized the study, oversaw the statistical analysis,

in learning. and led the writing of the manuscript. KD led the collection

of the data for the study and contributed to the writing of the

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT manuscript. JK performed the statistical analysis and contributed

to writing of the manuscript. SL contributed to writing of the

Data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved

available by the authors, without undue reservation. the submitted version.

ETHICS STATEMENT FUNDING

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and This research was supported in part by grants from the Centers

approved by University of Virginia, Social and Behavioral for Disease Control and Prevention through the Johns Hopkins

Sciences. Written informed consent for participation was not Center for the Prevention of Youth Violence, the National

required for this study in accordance with the national legislation Institute of Justice (2014-CK-BX-0005), and the Institute of

and the institutional requirements. Education Sciences (R305H150027).

REFERENCES Ramirez, M., Kubicek, K., Peek-Asa, C., and Wong, M. (2009). Accountability and

assessment of emergency drill performance at schools. Fam. Commun. Health

Bradshaw, C. P. (2015). Translating research to practice in bullying prevention. 32, 105–114. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e3181994662

Am. Psychol. 70, 322–332. doi: 10.1037/a0039114 Sugai, G., Lewis-Palmer, T. L., Todd, A. W., and Horner, R. H. (2001). School-Wide

Bradshaw, C. P., Milam, A. J., Furr-Holden, C. D. M., and Lindstrom Johnson, Evaluation Tool (SET). Eugene, OR: Center for Positive Behavioral Supports;

S. (2015). The School Assessment for Environmental Typology (SAfETy): an University of Oregon, 94–101

observational measure of the school environment. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. US Department of Education (2018). Final Report of the Federal Commission

56, 280–292. doi: 10.1007/s10464-015-9743-x on School Safety. US Department of Education. Available online at: https://

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., Debnam, K. J., and Lindstrom Johnson, www2.ed.gov/documents/school-safety/school-safety-report.pdf (Retrieved

S. (2014). Measuring school climate in high schools: a focus on safety, December 20, 2018).

engagement, and the environment. J. School Health 84, 593–604. US Department of Education Office of Safe and Drug-Free Schools (2003).

doi: 10.1111/josh.12186 Practical Information on Crisis Planning: A Guide for Schools and Communities.

Bradshaw, C. P., Waasdorp, T. E., and Leaf, P. J. (2012). Effects of school-wide US Department of Education.

positive behavioral interventions and supports on child behavior problems. Waasdorp, T. E., Lindstrom Johnson, S., Shukla, K., and Bradshaw, C. P. (2019).

Pediatrics 130, e1136–e1145. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0243 Measuring school climate: invariance across middle and high school students.

Cornell, D., Maeng, J., Burnette, A. G., Jia, Y., Huang, F., Konold, T., et al. Children Sch. 42, 53–62. doi: 10.1093/cs/cdz026

(2017). Student threat assessment as a standard school safety practice: White House (2013). Now Is the Time: The President’s Plan to Protect Our

results from a statewide implementation study. Sch. Psychol. Q. 33, 213–222. Children and Our Communities by Reducing Gun Violence. White House.

doi: 10.1037/spq0000220 Available online at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/

Cornell, D. G. (2020). Threat assessment as a school violence prevention strategy. docs/wh_now_is_the_time_full.pdf (Retrieved December 20, 2018).

Criminol. Publ. Policy 19, 235–252. doi: 10.1111/1745-9133.12471

Debnam, K. J., Pas, E. T., and Bradshaw, C. P. (2012). Secondary and tertiary Conflict of Interest: The authors declare that the research was conducted in the

support systems in schools implementing school-wide positive behavioral absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a

interventions and supports: a preliminary descriptive analysis. J. Posit. Behav. potential conflict of interest.

Intervent. 14, 142–152. doi: 10.1177/1098300712436844

Federal Bureau of Investigation (n.d.). Active Shooter Resources. Available online Publisher’s Note: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors

at: https://www.fbi.gov/about/partnerships/office-of-partner-engagement/ and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of

active-shooter-resources (Retrieved December 20, 2018).

the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in

Flannery, D. J., Bear, G., Benbenishty, R., Astor, R. A., Bradshaw, C. P., Sugai,

this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or

G., et al. (2019). “The scientific evidence supporting an eight point public

health oriented action plan to prevent gun violence,” in Keeping Students Safe endorsed by the publisher.

and Helping Them Thrive: A Collaborative Handbook on School Safety, Mental

Health and Wellness, Vol. 2, eds D. Osher, M. Mayer, R. Jagers, K. Kendziora, Copyright © 2022 Bradshaw, Debnam, Kush and Lindstrom Johnson. This is an

and L. Wood (New York, NY: Praeger), 227–255. open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution

Lindstrom Johnson, S., Bottiani, J., Waasdorp, T. E., and Bradshaw, C. License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted,

P. (2018). Surveillance or safekeeping? How school security officer and provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the

camera presence influence students’ perceptions of safety, equity, and original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic

support. J. Adolesc. Health 63, 732–738. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2018. practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply

06.008 with these terms.

Frontiers in Communication | www.frontiersin.org 5 February 2022 | Volume 7 | Article 765336

You might also like

- Preparing for Disaster: What Every Early Childhood Director Needs to KnowFrom EverandPreparing for Disaster: What Every Early Childhood Director Needs to KnowNo ratings yet

- Improving The Disaster Awareness and Preparedness of The Personnel and Students of Sta. Fe O-IT Elementary SchoolDocument6 pagesImproving The Disaster Awareness and Preparedness of The Personnel and Students of Sta. Fe O-IT Elementary SchoolPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Ready for Anything : A Guide to Disaster Preparedness and Family SafetyFrom EverandReady for Anything : A Guide to Disaster Preparedness and Family SafetyNo ratings yet

- Participation of Internal Stakeholders in School Disaster Riskreduction and Management Program Among Public Schools in Catanauan District: Basis For Developmental Training ProgramDocument14 pagesParticipation of Internal Stakeholders in School Disaster Riskreduction and Management Program Among Public Schools in Catanauan District: Basis For Developmental Training ProgramPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Thesis Final EditDocument27 pagesThesis Final EditJerson Dela TorreNo ratings yet

- Level of Awareness in Disaster Risk ReduDocument9 pagesLevel of Awareness in Disaster Risk ReduSheila MaliitNo ratings yet

- Reconfiguring Crisis Management Skills of Teachers in The New NormalDocument11 pagesReconfiguring Crisis Management Skills of Teachers in The New NormalIOER International Multidisciplinary Research Journal ( IIMRJ)100% (1)

- School Disaster Preparedness, Response and Recovery: Teachers in FocusDocument23 pagesSchool Disaster Preparedness, Response and Recovery: Teachers in FocusPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- PR 2Document13 pagesPR 2Harvey HailarNo ratings yet

- Crisis Preparedness and Response For Schools: An Analytical Study of Punjab, PakistanDocument9 pagesCrisis Preparedness and Response For Schools: An Analytical Study of Punjab, PakistanMico MaulanaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction: SciencedirectDocument10 pagesInternational Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction: SciencedirectDarwin TanNo ratings yet

- University of Perpetual Help System Dalta: Las Piñas CampusDocument25 pagesUniversity of Perpetual Help System Dalta: Las Piñas CampusMarj BaniasNo ratings yet

- University of Perpetual Help System Dalta: Las Piñas CampusDocument24 pagesUniversity of Perpetual Help System Dalta: Las Piñas CampusMarj BaniasNo ratings yet

- Assessmenrtof Disaster PreparednessDocument10 pagesAssessmenrtof Disaster PreparednessJovenil BacatanNo ratings yet

- Action ResearchDocument16 pagesAction ResearchTomas GuarinNo ratings yet

- Disaster Risk Reduction Knowledge Among Filipino Senior High School StudentsDocument18 pagesDisaster Risk Reduction Knowledge Among Filipino Senior High School StudentsProfTeng DePano RecenteNo ratings yet

- School Disaster Risk Reduction Management Program (SDRRMP) Effectiveness: Input To Students' Awareness and Participation in Natural Disaster Prevention and MitigationDocument6 pagesSchool Disaster Risk Reduction Management Program (SDRRMP) Effectiveness: Input To Students' Awareness and Participation in Natural Disaster Prevention and MitigationPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Emergency Preparedness Amongst Universit20161013 6965 Ejxyqq With Cover Page v2Document6 pagesEmergency Preparedness Amongst Universit20161013 6965 Ejxyqq With Cover Page v2Marj BaniasNo ratings yet

- GROUP D. Chapters 1 3Document13 pagesGROUP D. Chapters 1 3Marj BaniasNo ratings yet

- Reopening of Classes..Document53 pagesReopening of Classes..nbnt6xj7t2No ratings yet

- Research Title Proposal Format 404Document9 pagesResearch Title Proposal Format 404lloydhanz mahawanNo ratings yet

- Two Layer ML Student DODocument12 pagesTwo Layer ML Student DOannalystatNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Preparedness On Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Measures Among Public Senior High Schools in The Division of Batangas CityDocument8 pagesTeachers' Preparedness On Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Measures Among Public Senior High Schools in The Division of Batangas CityInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Group 1Document6 pagesChapter 1 - Group 1NATHANIEL YACASNo ratings yet

- Combating Urban Hazard A Qualitative Study On The Perception On Disaster Preparedness of STEM StudentsDocument43 pagesCombating Urban Hazard A Qualitative Study On The Perception On Disaster Preparedness of STEM StudentsChlarisse Gabrielle TanNo ratings yet

- SR 20404215026Document13 pagesSR 20404215026Frencis Jan Cabanting CalicoNo ratings yet

- Original ResearchDocument8 pagesOriginal ResearchMarj BaniasNo ratings yet

- Extent of Disaster Risk Reduction Management in Selected Elementary Schools: Evidence From The PhilippinesDocument19 pagesExtent of Disaster Risk Reduction Management in Selected Elementary Schools: Evidence From The PhilippinesJane EdullantesNo ratings yet

- Research. Disater and Emergency PreparednessDocument11 pagesResearch. Disater and Emergency PreparednessNisperos Soridor MadelNo ratings yet

- Finaloutline DDocument14 pagesFinaloutline DANGEL MAG-ASONo ratings yet

- Disaster Risk Reduction Knowledge Among Filipino Senior High School Students 2Document19 pagesDisaster Risk Reduction Knowledge Among Filipino Senior High School Students 2Melvin Dela CernaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 123 RevisedDocument23 pagesChapter 123 RevisedCristy Ann BallanNo ratings yet

- Sample Chapters 1 3Document38 pagesSample Chapters 1 3ARRA MAY ESTOCADONo ratings yet

- Disaster RoutingDocument57 pagesDisaster RoutingAnonymous 52ChTZ100% (1)

- Prac Research g12 1Document19 pagesPrac Research g12 1RaymondNo ratings yet

- Math ResearchDocument14 pagesMath ResearchBenedict BorjaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction: Alexa Tanner, Brent DobersteinDocument5 pagesInternational Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction: Alexa Tanner, Brent DobersteinMichael AquinoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document10 pagesChapter 1jamesmarkenNo ratings yet

- Concept PaperDocument14 pagesConcept PaperJOHANNES LATRASNo ratings yet

- Calagos JM GARDocument13 pagesCalagos JM GARIvy Moreno-Olojan JulatonNo ratings yet

- Research Senior HighDocument20 pagesResearch Senior HighCrisNo ratings yet

- 1 PB PDFDocument14 pages1 PB PDFFranken SteinNo ratings yet

- Assessment of School Security Practices Implemented at Visayas State University Tolosa in The New NormalDocument13 pagesAssessment of School Security Practices Implemented at Visayas State University Tolosa in The New NormalInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 1119pm - 95.epra Journals 7843Document12 pages1119pm - 95.epra Journals 7843Frances BlasNo ratings yet

- Enabling Risk Management and Adaptation To Climate Change Through A Network of Peruvian UniversitiesDocument16 pagesEnabling Risk Management and Adaptation To Climate Change Through A Network of Peruvian Universitiessantosml0408No ratings yet

- Bu-Cbem Students Teaching and Non-TeachiDocument64 pagesBu-Cbem Students Teaching and Non-TeachiJace RiveraNo ratings yet

- NURS FPX 6618 Assessment 3 Disaster Plan With Guidelines For ImplementationDocument4 pagesNURS FPX 6618 Assessment 3 Disaster Plan With Guidelines For ImplementationEmma WatsonNo ratings yet

- 2014-VA Report 2008Document92 pages2014-VA Report 2008ar.ryanortigasNo ratings yet

- The Importance of DRRR SubjectDocument9 pagesThe Importance of DRRR SubjectPatricia Laine Manila80% (5)

- The SPARS Pandemic 2025-2028 - A Futuristic Scenario To FacilitateDocument32 pagesThe SPARS Pandemic 2025-2028 - A Futuristic Scenario To FacilitateBuku OranyeNo ratings yet

- Bauan Technical High SchoolDocument61 pagesBauan Technical High SchoolShieshie CalderonNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Science DirectDocument9 pagesJurnal Science DirectAnnisa Nur RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Description: Tags: CrisisplanningDocument2 pagesDescription: Tags: Crisisplanninganon-967115No ratings yet

- Implementation of Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Program in Selected Schools in Region XII, PhilippinesDocument14 pagesImplementation of Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Program in Selected Schools in Region XII, PhilippinesPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- 4 1 1 An Analysis On Rapid AssessmentDocument4 pages4 1 1 An Analysis On Rapid AssessmentHannah DuyagNo ratings yet

- Proposal Manuscript FinalDocument26 pagesProposal Manuscript FinalCharlieNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2212420919305564 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S2212420919305564 MainFarid FauziNo ratings yet

- Project SafeDocument6 pagesProject SafeCarl Jay IntacNo ratings yet

- Sample Full Paper PR2Document19 pagesSample Full Paper PR2rose anne fajardoNo ratings yet

- Development of Preparedness Competencies in Basic Education Science Curriculum An Insight From The 8578Document3 pagesDevelopment of Preparedness Competencies in Basic Education Science Curriculum An Insight From The 8578Cairy AbukeNo ratings yet

- Chap 1 Intro To Advanced EMT PracticeDocument39 pagesChap 1 Intro To Advanced EMT PracticeAbu YazanNo ratings yet

- Mmeirs 2004Document34 pagesMmeirs 2004Alvin ClaridadesNo ratings yet

- GE8071Document6 pagesGE8071smkcse21No ratings yet

- Advisory VIII Dated 16.06.2021Document41 pagesAdvisory VIII Dated 16.06.2021KislayNikharNo ratings yet

- Confined Space RescueDocument490 pagesConfined Space RescueleeNo ratings yet

- Port of PT Lisas Risk AssessmentDocument38 pagesPort of PT Lisas Risk AssessmentAnonymous FmXEu2cHxKNo ratings yet

- Disaster Risk Reduction and Management in The PhilippinesDocument32 pagesDisaster Risk Reduction and Management in The PhilippinesErnan BaldomeroNo ratings yet

- Aapda Samvaad January, 2019Document13 pagesAapda Samvaad January, 2019Ndma IndiaNo ratings yet

- NARRATIVE REPORT - NDRRMCDocument5 pagesNARRATIVE REPORT - NDRRMCMa Theresa Nunezca TayoNo ratings yet

- Framework Review Eoc NetDocument2 pagesFramework Review Eoc NetNishtha BhawalpuriaNo ratings yet

- Security HandbookDocument80 pagesSecurity HandbookPradeep AvanigaddaNo ratings yet

- Pre-Embark Routine - Peregrino Field: WHP A, WHP B, Fpso and Whpc-Ums OlympiaDocument2 pagesPre-Embark Routine - Peregrino Field: WHP A, WHP B, Fpso and Whpc-Ums OlympiaArtur CurtinhasNo ratings yet

- Disaster Readiness and Risk ReductionDocument14 pagesDisaster Readiness and Risk ReductionJayson DesearNo ratings yet

- Lerbinger - The Crisis ManagerDocument41 pagesLerbinger - The Crisis ManagerTania Nicoleta100% (3)

- Emergency Preparedness and Response PlanDocument45 pagesEmergency Preparedness and Response Planfrederick Adeniyi Abiola100% (3)

- Calamity and Disaster Preparedness Chapter IXDocument34 pagesCalamity and Disaster Preparedness Chapter IXANGEL ALBERTNo ratings yet

- Basic Incident Command SystemDocument2 pagesBasic Incident Command SystemJango GulimanNo ratings yet

- DOH Orientation On PSCP - Public VersionDocument119 pagesDOH Orientation On PSCP - Public VersionNursing Staff Development Dr. PJGMRMCNo ratings yet

- Summary of NDRF Courses For The Year 2024Document2 pagesSummary of NDRF Courses For The Year 2024vigneshnrynnNo ratings yet

- Emergency Preparedness Overview: Fall 2016Document20 pagesEmergency Preparedness Overview: Fall 2016ahmed mzoreNo ratings yet

- Natural HazardsDocument20 pagesNatural Hazardshenry_koechNo ratings yet

- Publ 03Document18 pagesPubl 03olajummy675No ratings yet

- Engineering in The Post-Covid WorldDocument2 pagesEngineering in The Post-Covid WorldOliver Linus SundayNo ratings yet

- Disaster Risk Reduction Network Philippines (Drrnetphils) : Experience On Policy AdvocacyDocument19 pagesDisaster Risk Reduction Network Philippines (Drrnetphils) : Experience On Policy AdvocacyMICHAELA JOYCE GUZMANNo ratings yet

- Lbna 27533 EnnDocument43 pagesLbna 27533 EnnsugendengalNo ratings yet

- Devt of Erp & Role of Bomba.Document85 pagesDevt of Erp & Role of Bomba.Alex ChenNo ratings yet

- US COVID-19 Response PlanDocument103 pagesUS COVID-19 Response PlanCandy CaneNo ratings yet

- Self Declaration Form Details For International Arriving PassengersDocument2 pagesSelf Declaration Form Details For International Arriving PassengersKoteswar MandavaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Science & Disaster ManagementDocument104 pagesEnvironmental Science & Disaster ManagementJyothis T SNo ratings yet

- DHCC OHSE Policies Regulations & Guidelines EP-07 v6.0Document64 pagesDHCC OHSE Policies Regulations & Guidelines EP-07 v6.0Gideon SanthoshNo ratings yet