Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mobile and Ubiquitous Learning in Higher Education Settings. A Systematic Review of Empirical Studies - ScienceDirect

Uploaded by

07104336Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mobile and Ubiquitous Learning in Higher Education Settings. A Systematic Review of Empirical Studies - ScienceDirect

Uploaded by

07104336Copyright:

Available Formats

Journals & Books Search ScienceDirect My Account Sign in

Access through your institution Purchase PDF Search ScienceDirect

Article preview Recommended articles

Computers in Human Behavior

Abstract Volume , October , Pages -

WhatsApp for mobile learning. Effects on

Introduction knowledge, resilience and isolation in the…

The Internet and Higher Education, Volume , ,…

Section snippets Review

Christoph Pimmer, …, Ademola J. Ajuwon

References ( ) Mobile and ubiquitous learning in higher

Mobile Learning (M-Learning) adoption in

Cited by ( ) education settings. A systematic review of the Middle East: Lessons learned from the…

empirical studies Telematics and Informatics, Volume

Asharul Islam Khan, …, Mohamed Sarrab

, Issue , ,…

Ask Copilot: Save time, read 10X faster with AI Facilitating professional mobile learning

communities with instant messaging

Save Related Papers Purpose Summarize Conclusions

Computers & Education, Volume , , pp. -

Christoph Pimmer, …, Ademola J. Ajuwon

Key Takeaways Points Discussed Evidence/Examples Used

Show more articles

Christoph Pimmer a , Magdalena Mateescu b , Urs Gröhbiel a

Show more

Article Metrics

Share Cite

Citations

https://doi.org/ . /j.chb. . . Get rights and content

Citation Indexes:

Policy Citations:

Captures

Highlights

Readers:

• Systematic review to study mobile and ubiquitous learning in higher

education. Mentions

• Positive outcomes associated mainly with instructionist and hybrid designs. Blog Mentions:

• Instructionist benefits caused by more frequent learning activities. Social Media

• Hybridisation links formal education with informal and personalized Shares, Likes & Comments:

learning.

• Limited evidence to legitimize broad application of mobile learning in HE. View details

Abstract

Mobile and ubiquitous learning are increasingly attracting academic and public interest,

especially in relation to their application in higher education settings.

The systematic analysis of 36 empirical papers supports the view that knowledge gains

from instructionist learning designs are facilitated by distributed and more frequent

learning activities enabled by push mechanisms. They also lend themselves to the

activation of learners during classroom lectures. In addition, and as a particular

advantage of mobile technology, “hybrid” designs, where learners create multimodal

representations outside the classroom and then discussed their substantiated

experiences with peers and educators, helped to connect learning in formal and more

informal and personalized learning environments.

Generally, empirical evidence that would favour the broad application of mobile and

ubiquitous learning in higher education settings is limited and because mobile learning

projects predominantly take instructionist approaches, they are non-transformatory in

nature. However, by harnessing the increasing access to digital mobile media, a number

of unprecedented educational affordances can be operationalised to enrich and extend

more traditional forms of higher education.

Introduction

Like no previous technology, mobile technology has spread at an unprecedented pace in

the last few years. For example, in 2014, the number of mobile phone subscriptions

reached six billion (ITU, 2014). Mobile devices are considered cultural tools that are

transforming socio-cultural practices and structures in all spheres of life (Pachler,

Bachmair, & Cook, 2010). This transformation is considered central even from an

evolutionary perspective because it empowers humankind to engage in interactions that

are free from the constraints of physical proximity and spatial immobility for the first

time (Geser, 2004). Digital mobile devices such as cell phones, PDAs, and smart phones

are also being used increasingly often for educational purposes. The educational use of

digital mobile technology is at the core of vibrant and expanding streams of research

known as mobile and ubiquitous learning. Both concepts are strongly interconnected.

While some authors describe ubiquitous learning as a next-generation form of mobile

learning where technology fades more into the background (Park, 2011), the terms are

often used interchangeably (Hwang & Tsai, 2011). In essence, both approaches strongly

emphasise the notion of ’context’ in learning. The field of mobile learning conceives the

crossing of contexts as one of its constitutional characteristics (Pimmer, 2016). For

example, in one the most widely accepted definitions, Sharples, Taylor, and Vavoula

(2007) define mobile learning as ”the processes of coming to know through conversations

across multiple contexts among people and personal interactive technologies“. Similarly, in

ubiquitous learning studies, mobile and portable technologies are conceived either as

tools that allow learners to access information irrespective of their physical context, for

example on a bus (Chen, Chang, & Wang, 2008) or, alternatively, as a way to provide

learners with location-based information, for example while they are exploring a

butterfly garden (Liu & Hwang, 2010).

To ground the present research on prior literature, the two underlying tenets are briefly

and selectively introduced in the next sections: findings from prior mobile and

ubiquitous learning studies, and, more broadly, the role of digital media in higher

education settings.

To date, the educational qualities of mobile and ubiquitous learning have been examined

in a number of settings: in formal education settings in and outside the classroom (e.g.

Frohberg, Göth, & Schwabe, 2009), in the workplace (e.g., Pimmer & Pachler, 2014), and in

the context of lifelong learning (e.g., Sharples, 2000). Regarding higher education, some

authors expect mobile learning to radically transform this field by providing “new

strategies, practices, tools, applications, and resources to realise the promise of ubiquitous,

pervasive, personal, and connected learning” (Wagner, 2005). Two recent meta studies

provide an overview of and insights into the emerging socio-technical phenomenon

(Hwang and Tsai, 2011, Wu et al., 2012). Wu et al. (2012) found in their meta-analysis that

research has most commonly concentrated on the effects of mobile learning, followed by

design aspects, the investigation of the affective domain during mobile learning and the

analysis of learners’ characteristics. Regarding the course subjects, mobile learning was

studied primarily in the setting of language and linguistics courses, followed by

computer classes and health sciences (Wu et al., 2012). The authors also noted the

predominance of higher education settings among mobile learning environments; more

than half of the learners included in the meta-analysis were from post-secondary

education environments (Wu et al., 2012). Similarly, Hwang and Tsai (2011) reported that

higher education students were the most often researched target group for mobile

learning studies. Notably, in both meta-analyses, most of the included studies reported

positive learning outcomes.

In these reviews, relatively little attention was paid to the different forms, practices and

outcomes of mobile learning and their theoretical underpinnings. For example, in the

instructionist sense of learning, mobile devices can be used to test vocabulary (Brett,

2011), while a constructionist approach might have students use mobile devices to create

video materials (Zahn et al., 2013). While both uses could be labelled “mobile learning”,

the associated learning activities and underlying theories are diverse and are likely to

result in different forms of engagement and educational effects. One of the first reviews

that differentiated mobile learning on the basis of different theoretical strands was

written by Naismith, Lonsdale, Vavoula, and Sharples (2004). They distinguished

behaviourist, constructivist, situated, collaborative, informal and lifelong learning

categories. Their review, however, was based on examples and was not systematic.

Another literature analysis was conducted by Frohberg et al. (2009). In their critical

review of mobile learning projects, the authors used activity theory (Engeström, 1987,

Sharples et al., 2007) as an analytical framework. They analysed more than 100 projects

according to the categories context, tools, control, communication, subject and objective.

Frohberg et al. (2009) observed that although mobile phones are primarily

communication devices, communication and social interaction played a surprisingly

small role in mobile learning projects. However, the reviewers did not focus on higher

education settings, and more importantly, their review included projects that were

published before the end of 2007. As noted in subsequent systematic reviews, the

number of mobile learning studies increased sharply after this period (Hwang and Tsai,

2011, Wu et al., 2012). In the more recent analysis of mobile lifelong learning projects,

Arrigo, Kukulska-Hulme, Arnedillo-Sánchez, and Kismihok (2013) also suggest that most

of the projects were centred on the distribution of content instead of on social

interaction between tutors, teachers or peers using mobile devices.

More generally, the use and role of digital technology in higher education is contested. Its

transformational potential has been frequently stressed by some scholars, especially if

online learning is blended with face-to-face teaching. Garrison and Kanuka (2004) argue,

for example, that these formats have started to question the ”dominance of the lecture in

favor of more active and meaningful learning activities and tasks“ (p. 100). Specific reviews,

for example from the field of health professions, reveal moderately positive results to

date. Although internet-based education formats are associated with large positive

effects compared with no interventions, they show a similar effectiveness when

compared with traditional non-internet-based teaching (Cook et al., 2008a). Beyond the

outcomes of specific interventions, authors who consider the “bigger picture” of higher

education are more critical. It is argued that, despite the abundance of digital

technologies, the usage of new technologies in higher education is sporadic, uneven and

rigid (Selwyn, 2007) and concentrates on the content-driven reproduction of

behaviourist educational patterns (Blin & Munro, 2008). This is reflected in Cuban,

Kirkpatrick, and Peck (2001) study, in which they observed that access to digital

technology did not lead to its widespread use; and, when used, computers sustained

rather than changed existing teaching practice. They explain this tendency with a lack of

time and ICT training on the teachers’ part (2001). In addition to teachers, students are

also affected by constraints in the use of online learning in higher education, for example

regarding the lack of a sense of community in online environments, difficulties in

understanding learning goals and technical problems (Song, Singleton, Hill, & Koh, 2004).

Cuban et al. (2001) tie the modest adaptation of digital technology to the concept of a

’slow’ revolution, which means that individuals and organisations require decades to

learn how to fully use and exploit new technologies. While the observations of Cuban

et al. (2001) were made in a high school context, the arguments regarding slow change

patterns were also found in higher education settings, with digital technology being

gradually adopted over decades in ways that improve existing practices, rather than

radically changing them (Kirkup & Kirkwood, 2005).

To conclude this introduction, after more than 20 years of mobile learning research there

is still relatively little systematic knowledge available, especially regarding the use of

mobile technology in different educational designs and with associated educational

effects in higher education settings. Of interest is also the question whether, and if so,

how a technology marked by many as “revolutionary” can impact on established learning

and teaching in a context which appears to be resistant to change.

Section snippets

Research question and goal

This review intends to address the following broadly focused research question: How can

mobile and ubiquitous learning formats in higher education be synthesized according to

their theoretical underpinnings and to what extent are these categories tied to different

educational outcomes? Addressing these questions is expected to result in a more

nuanced and theoretically grounded understanding of the pedagogical effects of different

mobile learning arrangements.…

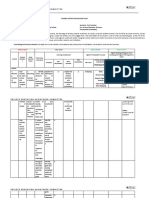

Search strategies and techniques

The overall procedure followed the steps that Cook and West (2012) suggested for

conducting systematic reviews. First, the research questions, as stated above was

defined; this was followed by protocol writing, the search for eligible studies, decisions

about inclusion/exclusion criteria, the review of title abstracts, and the actual analysis.

Finally, the synthesis was written up. Mobile and ubiquitous learning activities can be

highly diverse, offering different educational qualities and…

Data coding and analysis

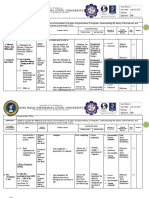

Based on the criteria, 36 studies were identified as eligible for the review and were

comprehensively analysed by two of the authors. The analytical process included the

reading, re-reading and analysis of the papers according to the following parameters: The

main analytical parameter was the educational design and the underlying theoretical

orientation. The analysis for this category was applied in a semi-grounded way: The

investigation started with a synthesis of categories from previous…

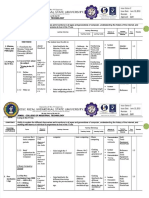

Characterisation of the sample

In the 36 examined papers, 47 educational designs were identified. Of those designs,

instructionism was by far the most prevalent category: 22 studies in which instructional

elements formed a central part of the didactic design were identified. This was followed

by constructionist learning (13) and situated action (12). In addition, 6 studies were

characterised by a hybrid of situated, constructionist and collaborative designs. From a

geographical perspective, the majority of the studies were…

Results: pedagogical strategies and outcomes

In the following sections, the usage and outcomes of mobile and ubiquitous learning are

synthesised and presented according to the categories of (1) instructionism, (2) situated

action and contextual scaffolding, (3) constructionist and collaborative learning and (4)

hybrids of situated, constructionist and collaborative designs.…

Instructionist education

Instructionism, as characterised by Laurillard (2009) - who is, in turn, referring to

Seymour Papert (e.g., 1991) - puts the focus on the organisation of instruction and is

teacher driven and prescriptive. Instructionism is rooted in the broader psychological

concept of behaviourism, which highlights the stimulus-response mechanism.

Considering the role of technology, this means using computers to instruct learners or

even having computers present the instruction. Instructionism places the…

Situated action and contextual scaffolding

Situated action focuses on the learners’ responsiveness to their environments and the

ways in which human action arises in “the flux of real activity” (Nardi, 1996). In terms of

educational design, this means facilitating problem solving and inquiry-based learning.

Compared to instructionism, situated action learning occurs in a more spontaneous and

fluid and much less teacher-guided way in authentic and real-life situations. Instead of

controlling and assessing each behaviour, learners should…

Constructionist learning

This paradigm is centred on the notions of construction and co-construction as a process

of learning. As coined by Papert and Harel (1991), constructionism emphasises learning

by making something that makes sense in the real life of the learners. This process can

involve making “real” objects, such as building a sand castle, or virtual entities, such as

programming digital calendars. Constructionist approaches also embrace social learning

settings, thus involving co-construction by groups or…

Discussion and critical analysis

In the following sections, the main findings are synthesised (see also Table 1) and

critically discussed, especially in view of the broader use of mobile and ubiquitous

learning in higher education.…

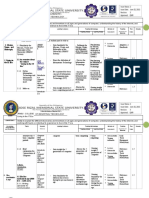

Conclusion

Instructionist qualities of mobile learning applications in higher education that are based

on the presentational and testing capabilities of mobile devices can facilitate distributed

and more frequent practice and can activate learners in and across classrooms. Beyond

instructionism, the hybridisation of situated, collaborative and constructionist

approaches via the use of mobile devices can also create new and unprecedented

educational opportunities. This integration can result in situated…

References (93)

F. Blin et al.

Why hasn’t technology disrupted academics’ teaching practices?

Understanding resistance to change through the lens of activity theory

Computers & Education ( )

C.-C. Chang et al.

Is single or dual channel with different english proficiencies better for english

listening comprehension, cognitive load and attitude in ubiquitous learning

environment?

Computers and Education ( )

G.-D. Chen et al.

Ubiquitous learning website: scaffold learners by mobile devices with

information-aware techniques

Computers & Education ( )

N. Dabbagh et al.

Personal Learning Environments, social media, and self-regulated learning: a

natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning

The Internet and higher education ( )

J.S. Davis et al.

Identifying pitfalls in chest tube insertion: improving teaching and

performance

Journal of Surgical Education ( )

L. De-Marcos et al.

An experiment for improving students performance in secondary and tertiary

education by means of m-learning auto-assessment

Computers & Education ( )

N.J. Entwistle et al.

Conceptions of learning and knowledge in higher education: relationships with

study behaviour and influences of learning environments

International Journal of Educational Research ( )

C. Evans

The effectiveness of m-learning in the form of podcast revision lectures in

higher education

Computers & education ( )

Q. Gao et al.

To ban or not to ban: differences in mobile phone policies at elementary,

middle, and high schools

Computers in Human Behavior ( )

B.M. Garrett et al.

A mobile clinical e-portfolio for nursing and medical students, using wireless

personal digital assistants (PDAs)

Nurse Education in Practice ( )

View more references

Cited by (213)

Chat-GPT; validating Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) in education sector

via ubiquitous learning mechanism

, Computers in Human Behavior

Show abstract

M-Learning adoption in higher education towards SDG4

, Future Generation Computer Systems

Show abstract

Orchestrating ubiquitous learning situations about Cultural Heritage with

Casual Learn mobile application

, International Journal of Human Computer Studies

Citation Excerpt :

…The learning situations involved five teachers and 139 students from two secondary schools of

the Spanish region of Castile and Leon. In addition to the expansion of the empirical evidence about

the affordances and limitations of UL, a need that has been explicitly pointed out in the literature

(see, e.g., Pimmer et al., 2016), the findings from the presented study can be significant to the field

of technology-enhanced UL and HCI for several reasons: they can help researchers to better

understand the particularities of orchestration in the Cultural Heritage learning field; they lead to

design recommendations that can help to improve the support of orchestration of UL; and they can

help designers of secondary-education teachers training programs identify skills that teachers need

to design UL situations supported by mobile technologies. The rest of the paper is structured as

follows: Section 2 summarizes several approaches to orchestrate UL situations.…

Show abstract

Students’ perceptions of smartphone use: Institutional policies in Assam, India

, E-Learning and Digital Media

A Systematic Review of Research on Immersive Technology-Enhanced Writing

Education: The Current State and a Research Agenda

, IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies

A cross-database bibliometric analysis of ubiquitous learning: Trends,

influences, and future directions

, Contemporary Educational Technology

View all citing articles on Scopus

www. nw.ch .

View full text

© Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

About ScienceDirect Remote access Shopping cart Advertise Contact and support Terms and conditions Privacy policy

Cookies are used by this site. Cookie Settings

All content on this site: Copyright © Elsevier B.V., its licensors, and contributors. All rights are reserved, including those for text and data mining, AI training, and similar technologies. For all open access content, the Creative Commons licensing terms apply.

You might also like

- Exploring Critical Success Factors of Mobile Learning As Perceived by Students of The College of Computer Studies - National UniversityDocument1 pageExploring Critical Success Factors of Mobile Learning As Perceived by Students of The College of Computer Studies - National University07104336No ratings yet

- Research Method in Education MPPU 1024-52 Assignment 1 Journal ReviewDocument6 pagesResearch Method in Education MPPU 1024-52 Assignment 1 Journal ReviewNiza ZainulNo ratings yet

- Active Learning and Machine Teaching For Online Learning A Study of Attention and Labelling CostDocument6 pagesActive Learning and Machine Teaching For Online Learning A Study of Attention and Labelling CostZaeem AbbasNo ratings yet

- Midrange Exploration Exploitation Searching Particle Swarm Optimization in Dynamic EnvironmentDocument6 pagesMidrange Exploration Exploitation Searching Particle Swarm Optimization in Dynamic EnvironmentnorshamsiahibrahimNo ratings yet

- Q3 - Grade 4 - Summary of QAsDocument4 pagesQ3 - Grade 4 - Summary of QAsArthur Jan BoreborNo ratings yet

- 2018 - Utilization of Expert System in Learning InvertebrateDocument8 pages2018 - Utilization of Expert System in Learning InvertebrateYasinta LisaNo ratings yet

- Xa DiscussionvisualDocument1 pageXa Discussionvisualapi-448283923No ratings yet

- Gee Ie Living in The It Era SyllabuspdfDocument13 pagesGee Ie Living in The It Era SyllabuspdfReygenMae SubangNo ratings yet

- FIDP TemplateDocument3 pagesFIDP TemplateJovi AbabanNo ratings yet

- Lecturer Profile: Component Information StuffingDocument3 pagesLecturer Profile: Component Information StuffingNadhila RamadhaniNo ratings yet

- Webinar 3 Dec 2020Document11 pagesWebinar 3 Dec 2020Gabriela GrosseckNo ratings yet

- Alzubi 2018 J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1142 012012Document23 pagesAlzubi 2018 J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1142 012012bari12841No ratings yet

- Syllabus - Object Oriented Programming (Java)Document14 pagesSyllabus - Object Oriented Programming (Java)Jocelyn BalolotNo ratings yet

- 3 Ways Technology Is Changing Studying - EdTech MagazineDocument4 pages3 Ways Technology Is Changing Studying - EdTech MagazineGabrielGarciaOrjuelaNo ratings yet

- Ivory Parel RRLand RRSDocument23 pagesIvory Parel RRLand RRSMark garciaNo ratings yet

- VR1 s2.0 S1877050922022116 MainDocument7 pagesVR1 s2.0 S1877050922022116 MainAisyah Rahma NstNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1877050922006202 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S1877050922006202 MainZainab RamzanNo ratings yet

- BootDocument1 pageBootKarthik Sara MNo ratings yet

- Aguilar Al2016Document8 pagesAguilar Al2016Abdelouahab BelazouiNo ratings yet

- Communications201010 DLDocument116 pagesCommunications201010 DLhhhzineNo ratings yet

- Senticnet 6: Ensemble Application of Symbolic and Subsymbolic Ai For Sentiment AnalysisDocument10 pagesSenticnet 6: Ensemble Application of Symbolic and Subsymbolic Ai For Sentiment AnalysisAleksandar CenicNo ratings yet

- Intelligent Tutoring Systems For Generation Z's Addiction: Ioana R. Goldbach Felix G. Hamza-LupDocument4 pagesIntelligent Tutoring Systems For Generation Z's Addiction: Ioana R. Goldbach Felix G. Hamza-LupIoana GoldbachNo ratings yet

- Living in The It Era SyllabusDocument12 pagesLiving in The It Era Syllabuskwinhie MascardoNo ratings yet

- ICMASTS-2024Document2 pagesICMASTS-2024Syed AfwAnNo ratings yet

- Virtual Project ManagementDocument2 pagesVirtual Project ManagementJames OReillyNo ratings yet

- Mindmap 2050Document1 pageMindmap 2050Daniel MagpantayNo ratings yet

- GEE IE Living in The IT Era Syllabus PDFDocument12 pagesGEE IE Living in The IT Era Syllabus PDFCosmos LeonhartNo ratings yet

- A. Key Loggers: Sumer - Ftc.gov/to Pics/online-SecurityDocument27 pagesA. Key Loggers: Sumer - Ftc.gov/to Pics/online-Securityenajaral17No ratings yet

- Week 9.Document13 pagesWeek 9.Althaf MubinNo ratings yet

- Business Canvas Model 070123Document1 pageBusiness Canvas Model 070123Joaquin DiazNo ratings yet

- Isolation Forest Based Anomaly Detection: A Systematic Literature ReviewDocument5 pagesIsolation Forest Based Anomaly Detection: A Systematic Literature ReviewGandhimathinathanNo ratings yet

- Semantic Web and Ontology Engineering: ITKS544Document78 pagesSemantic Web and Ontology Engineering: ITKS544ewelinszNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning Based Smart Assistive Device For Differently Abled People-SADDAPDocument7 pagesMachine Learning Based Smart Assistive Device For Differently Abled People-SADDAP1SI19CS076 MEHUL BHARDWAJNo ratings yet

- Asynchronous Task Session Plan On 21Document5 pagesAsynchronous Task Session Plan On 21Jayson Jerald RiveraNo ratings yet

- Industrial Engineering Department Course Syllabus Information Systems (IE 54) 1st Semester, SY 2018 - 2019Document6 pagesIndustrial Engineering Department Course Syllabus Information Systems (IE 54) 1st Semester, SY 2018 - 2019TrixiNo ratings yet

- LHT 04 2016 0038Document21 pagesLHT 04 2016 0038Havidz Kus HidayatullahNo ratings yet

- A Novel Edge-Based Multi-Layer Hierarchical Architecture For Federated LearningDocument5 pagesA Novel Edge-Based Multi-Layer Hierarchical Architecture For Federated LearningAmardip Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Empowerment Technologies CM 1Document3 pagesEmpowerment Technologies CM 1Kim Lawrence R. BalaragNo ratings yet

- J Procs 2017 10 011Document13 pagesJ Procs 2017 10 011Wildan ArmyNo ratings yet

- IT 101 Introduction To Computing EDITEDDocument8 pagesIT 101 Introduction To Computing EDITEDAlvinNo ratings yet

- Integrating Machine Learning With Human KnowledgeDocument27 pagesIntegrating Machine Learning With Human KnowledgeLe Minh Tri (K15 HL)No ratings yet

- Yuliansyah 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. - Earth Environ. Sci. 258 012053Document8 pagesYuliansyah 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. - Earth Environ. Sci. 258 012053Amelia Yulian SariNo ratings yet

- Machine Learning From Theory To Algorithms: An: Journal of Physics: Conference SeriesDocument16 pagesMachine Learning From Theory To Algorithms: An: Journal of Physics: Conference SeriesMoohammed J Yaghi100% (1)

- 3Q Science 7 PCO AY 2023-2024 V1Document3 pages3Q Science 7 PCO AY 2023-2024 V1Aiza CabatinganNo ratings yet

- Virgen Milagrosa University FoundationDocument8 pagesVirgen Milagrosa University Foundationsyrel s. olermoNo ratings yet

- 10 3390@s19153260Document8 pages10 3390@s19153260mohamedNo ratings yet

- Brown and White Doodle Mind Map Brainstorm GraphDocument1 pageBrown and White Doodle Mind Map Brainstorm GraphSri RetinaNo ratings yet

- Idp Debelen Annamarie 2023-2024Document2 pagesIdp Debelen Annamarie 2023-2024Anna Marie BautistaNo ratings yet

- Course Outline AND LESSON pLANDocument4 pagesCourse Outline AND LESSON pLANabh ljknNo ratings yet

- A Review On Computational Methods Based On Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques For Malaria DetectionDocument5 pagesA Review On Computational Methods Based On Machine Learning and Deep Learning Techniques For Malaria DetectionGopi ChandNo ratings yet

- Mobile Learning in Developing Countries A Synthesis of The Past To Define The FutureDocument8 pagesMobile Learning in Developing Countries A Synthesis of The Past To Define The FutureArul ArunNo ratings yet

- NIT Nagaland - Recent Trends in AI and ML - ATAL FDP Brouchure-1Document4 pagesNIT Nagaland - Recent Trends in AI and ML - ATAL FDP Brouchure-1Manish ShashikantNo ratings yet

- Identifico La Influencia de Factores Ambientales, Sociales, Culturales y Económicos en La Solución de ProblemasDocument4 pagesIdentifico La Influencia de Factores Ambientales, Sociales, Culturales y Económicos en La Solución de Problemassantilex bomber xdNo ratings yet

- Lyceum of The Philippines - Davao: Classroom Instruction Delivery Alignment MapDocument2 pagesLyceum of The Philippines - Davao: Classroom Instruction Delivery Alignment MapKeenly PasionNo ratings yet

- Raises Montessori Academe: Curriculum MapDocument8 pagesRaises Montessori Academe: Curriculum MapLara LealNo ratings yet

- Recommending Moodle Resources Using ChatbotsDocument4 pagesRecommending Moodle Resources Using ChatbotsZbryxnK AntonyNo ratings yet

- Week 8 - 9Document2 pagesWeek 8 - 9April Lourdes Punzalan AragonNo ratings yet

- Deep Learning Based Mobile Assistive Device For Visually Impaired PeopleDocument3 pagesDeep Learning Based Mobile Assistive Device For Visually Impaired PeopleLaksha SekarNo ratings yet

- LandscapeDocument1 pageLandscapeimanhimdyNo ratings yet

- Planning, Writing, and Revising: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument27 pagesPlanning, Writing, and Revising: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinFrandy KarundengNo ratings yet

- Music Chess and Other SinsDocument173 pagesMusic Chess and Other Sinstaher adelNo ratings yet

- Pojkars Problematiska Läsning - Kåkå OlsenDocument78 pagesPojkars Problematiska Läsning - Kåkå OlsenJoKristenssonNo ratings yet

- English 10-Q4-M9Document14 pagesEnglish 10-Q4-M9Joemar De Pascion Novilla100% (1)

- Film Gospodar Prstenova Na SrpskomDocument3 pagesFilm Gospodar Prstenova Na SrpskomArturoNo ratings yet

- I. Objectives: Grades 11 / 12 Daily Lesson Plan School Grade Level Teacher Learning Area Teaching Dates and Time QuarterDocument3 pagesI. Objectives: Grades 11 / 12 Daily Lesson Plan School Grade Level Teacher Learning Area Teaching Dates and Time QuarterChe RaveloNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Audio Visual MediaDocument26 pagesIntroduction To Audio Visual MediaAnup SemwalNo ratings yet

- West Bengal NSEJS 2011 CenterDocument5 pagesWest Bengal NSEJS 2011 CenteracNo ratings yet

- Bbu Strategic Plan For Mba Prog, 01.04Document3 pagesBbu Strategic Plan For Mba Prog, 01.04semchandaraNo ratings yet

- StoryboardDocument8 pagesStoryboardapi-4587398430% (1)

- Multiculturalism in PeruDocument13 pagesMulticulturalism in PerudollyNo ratings yet

- 2015 Draft of The UP Diliman Students Magna CartaDocument12 pages2015 Draft of The UP Diliman Students Magna CartaAnthony MNo ratings yet

- LGBT As Teachers: Perceptions of Colleagues and AdministratorsDocument2 pagesLGBT As Teachers: Perceptions of Colleagues and AdministratorsFaye LomibaoNo ratings yet

- EmotiPlay General Presentation (March 2015)Document19 pagesEmotiPlay General Presentation (March 2015)Ofer AtzmonNo ratings yet

- Organizational Psychodynamics (ENG) : Ten Introductory Lectures For Students, Managers and Consultants, Sofia-Blagoevgrad, 2008Document147 pagesOrganizational Psychodynamics (ENG) : Ten Introductory Lectures For Students, Managers and Consultants, Sofia-Blagoevgrad, 2008Drujestvo Na Psiholozite100% (1)

- Sle Rubric Formatted 8 PortfolioDocument2 pagesSle Rubric Formatted 8 Portfolioapi-317615280No ratings yet

- 1.RPMS Facilitator's GuideDocument95 pages1.RPMS Facilitator's GuidecatherinerenanteNo ratings yet

- The Bounce Back Initiative: " (One) Who Opens A School Door, Closes A Prison." - Victor HugoDocument13 pagesThe Bounce Back Initiative: " (One) Who Opens A School Door, Closes A Prison." - Victor Hugoapi-543066218No ratings yet

- Developing Trust in Virtual TeamsDocument26 pagesDeveloping Trust in Virtual TeamsbalbirNo ratings yet

- DLP MaramagDocument4 pagesDLP MaramagLara Angelica Dalugdug TipaneroNo ratings yet

- Updated ResumeDocument1 pageUpdated Resumeapi-458529604No ratings yet

- DSP by Avatar Singh PDFDocument355 pagesDSP by Avatar Singh PDFaravind_elec565479% (14)

- January 17th Bobcat TalesDocument7 pagesJanuary 17th Bobcat TalesmscheiffleeNo ratings yet

- CDS 1 English 2016Document24 pagesCDS 1 English 2016Sabyasachi DuttaNo ratings yet

- Feu Reflection Paper Format1Document5 pagesFeu Reflection Paper Format1Arly Tabarrejo0% (1)

- French Homework Help Ks3Document8 pagesFrench Homework Help Ks3afetvdqbt100% (1)

- PROF2Document7 pagesPROF2123genrevNo ratings yet

- Egg Safety Device and Lab Report Grading RubricsDocument2 pagesEgg Safety Device and Lab Report Grading Rubricsapi-290531794No ratings yet

- What Is TheoryDocument6 pagesWhat Is TheoryWarren ValdezNo ratings yet

- REME Instrument Tech&Mech Trade 1942 - 2002Document96 pagesREME Instrument Tech&Mech Trade 1942 - 2002Dave KnowlesNo ratings yet