Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2006, Videofeedback madres bulimicas y relacion infantil

Uploaded by

MariluzCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2006, Videofeedback madres bulimicas y relacion infantil

Uploaded by

MariluzCopyright:

Available Formats

Article

Treating Disturbances in the Relationship Between

Mothers With Bulimic Eating Disorders and Their Infants:

A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Video Feedback

Alan Stein, F.R.C.Psych. Pia Menzes, M.R.C.Psych. were infant weight, aspects of mother-in-

fant interaction, and infant autonomy.

Helen Woolley, B.A. Anne Schmidt, B.Sc. Results: Seventy-seven mothers were fol-

lowed up when their infants were 13

Robert Senior, M.R.C.Psych. Edmund Juszczak, M.Sc. months old. The video-feedback group

exhibited significantly less mealtime con-

Leezah Hertzmann, U.K.C.P. Christopher G. Fairburn, flict than the control subjects. Nine of 38

F.R.C.Psych. (23.7%) in the video-feedback group

Mary Lovel, U.K.C.P. showed episodes of marked or severe

Objective: Maternal eating disorders in- conflict, compared with 21 of 39 (53.8%)

Joanna Lee, C.Q.S.W. terfere with parenting, adversely affecting control subjects (odds ratio=0.27, 95%

mother-infant interaction and infant out- confidence interval=0.10 to 0.73). Video

Sandra Cooper, B.A. come. This trial tested whether video- feedback produced significant improve-

feedback treatment specifically targeting ments in several other interaction mea-

mother-child interaction would be supe- sures and greater infant autonomy. Both

Rebecca Wheatcroft, D.Clin.Psy. rior to counseling in improving mother- groups maintained good infant weight,

child interaction, especially mealtime with no differences between groups. Ma-

Fiona Challacombe, B.A. (Hons.) conflict, and infant weight and autonomy. ternal eating psychopathology was re-

Method: The participants were 80 moth- duced across both groups.

Priti Patel, M.R.C.Psych. ers with bulimia nervosa or similar eating

Conclusions: Video-feedback treatment

disorder who were attending routine

Rosemary Nicol-Harper, M.A. baby clinics and whose infants were 4–6

focusing on mother-infant interaction

months old. They were randomly as- produced improvements in interaction

signed to video-feedback interactional and infant autonomy, and both groups

treatment or supportive counseling. Both maintained adequate infant weight. To

groups also received guided cognitive be- the authors’ knowledge, this is the first

havior self-help for their eating disorder. controlled trial to show key improve-

Each group received 13 sessions. The pri- ments in interaction between mothers

mary outcome measure was mealtime with postnatal psychiatric disorders and

conflict; secondary outcome measures their infants.

(Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:899–906)

T here is accumulating evidence that maternal psychi-

atric disorders, including eating disorders, occurring in

are associated with lower infant weight (5, 6). Two mater-

nal responses are strongly associated with the develop-

the postnatal period are associated with adverse effects on ment of such conflict: where mothers do not detect and re-

child development (1–3). A key way in which these disor- spond to their infants’ signals and where mothers have

ders affect children’s development is by disrupting difficulty in allowing their infants to express age-appropri-

mother-infant interaction (2). Eating disorders are rela- ate needs for autonomy through self-feeding and experi-

tively common among women of childbearing age, affect- mentation with food. Mealtime conflict is therefore the

ing approximately 4% of women (4). The problems that end product of a series of episodes of poor parental re-

these women experience have a considerable impact on sponsiveness secondary to maternal eating psychopathol-

the mother-child relationship and on the child. Of partic- ogy centering on food and mealtimes. Furthermore, con-

ular concern is the findings that by their infants’ first flict in family relationships has been shown to have

birthday, mothers with eating disorders are more likely to adverse effects on child development (7).

be involved in major episodes of mealtime conflict with To our knowledge, there have been no published inter-

their infants than are comparison subjects, as well as hav- vention studies aimed at helping mothers with eating dis-

ing other interactional difficulties, and that these episodes orders and their young children. Studies of postnatal de-

Am J Psychiatry 163:5, May 2006 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 899

MOTHERS WITH BULIMIC EATING DISORDERS

pression have shown that while it is possible to improve not address the mother-infant interaction directly and has been

the mother’s psychological state, the interventions have shown to be an effective therapy for mothers with difficulties in

the postnatal period (13). In order to address the mother’s eating

limited impact on mother-child interaction or the child’s

disorder specifically, both groups also received guided cognitive

development (8). behavior self-help for eating disorders, which has been shown to

Video-feedback intervention to promote positive be suitable for use in primary care settings (14). It was modified for

parenting is a relatively new treatment that has been the postnatal period and administered during half of each of the

shown to be useful in helping mothers and infants at risk first eight sessions. As all of the therapies were nondirective, it was

possible to integrate the guided self-help with the other two thera-

(9), although we know of no studies to date that have in-

pies following pilot testing. All therapies were conducted accord-

cluded mothers with psychiatric disorders (10). The ing to standardized treatment protocols.

strength of video feedback is that it provides direct access The therapists (L.H., M.L., J.L.) were experienced in child and

to the details of mother-child interaction, rather than rely- family mental health care and undertook project-specific training.

ing on maternal perceptions and reports. The present Weekly team meetings, supervised by psychiatrists (including A.

Stein, R.S.), were held to discuss the progress of therapy and to re-

study was designed to test whether such a treatment, tar-

view videotapes and samples of tape recordings of the treatment

geted specifically at mother-child interaction, would di- sessions to ensure consistency and compliance with the protocol.

minish mealtime conflict by helping mothers recognize, The aim of the video-feedback treatment was to prevent or re-

support, and respond to infant signals and initiatives and duce mother-infant conflict and enhance mother-child interac-

whether it would increase infant weight and improve in- tion, principally during mealtimes, by facilitating maternal recog-

fant autonomy at mealtimes more than a control treat- nition of and responsiveness to her infant’s cues and by

improving her awareness of the infant’s developing skills and

ment in which mothers received counseling.

needs. The therapist videotaped the mother and infant at home

during mealtimes at alternate visits. At the following visits, the

Method therapist and mother watched and discussed extracts selected by

the therapist to highlight the infant’s signals and exploration and

Participants to draw out and enhance the mother’s observational skills. The

Eligible participants were women ages 18–45 years with infants baseline assessment videotape was used in the first session; thus,

between 4 and 6 months old. The women met the DSM-IV diag- seven videotapes were used in total.

nostic criteria for an eating disorder, either bulimia nervosa or a Treatment comprised three stages. The first concentrated on the

similar form of eating disorder of clinical severity, i.e., a bulimic infant’s perspective, focusing on his or her signals (initiatives to-

subtype of eating disorder not otherwise specified (4). The inclu- ward the mother, exploratory behavior, indications of hunger and

sion criteria were 1) overevaluation of body shape or weight to a satiety, and attempts at self-feeding). The second stage included

degree reaching clinical severity, 2) recurrent episodes of loss of the mother’s perspective, highlighting mother-infant initiatives,

control over eating (i.e., subjective or objective bulimic episodes), mutual responses, moments of shared emotion, and the success of

and 3) secondary social impairment. Mothers with severe comor- sensitive, prompt reactions to infant cues. Third, as treatment pro-

bid psychiatric disorders were excluded. gressed, the videotapes were used to help the mother identify and

In order to identify potential participants, women with infants address potential triggers of mealtime conflict.

ages 8–24 weeks attending routine postnatal baby clinics in north The counseling treatment provided the mother with support

London and Oxford, U.K., were screened by using the Eating Dis- specifically for herself by means of empathetic listening. It

order Examination Questionnaire (11) (adapted for postnatal helped the mother reflect on self-selected aspects of her life and

use). Informed consent was obtained for the two-stage screening related feelings. It aimed to encourage and support any changes

procedure. Women who showed evidence of significant distur- she initiated, thereby developing a sense of empowerment and

bance in eating habits and attitudes were invited for an interview self-confidence.

using the Eating Disorder Examination (12). Each woman who Mothers in both groups were provided with a self-help manual,

fulfilled the eligibility criteria was invited to participate in the trial adapted for the postnatal period from two established treatments

and was visited at home by a psychiatrist (A. Stein or one of two (15, 16), that contained information about eating problems and

other psychiatrists), who confirmed the diagnosis by clinical in- explained the program’s six steps. The guided cognitive behavior

terview. After complete description of the trial, written informed self-help treatment aimed to help the mother regain control over

consent was obtained. The study was approved by the relevant lo- her eating, reduce vomiting and laxative use, and reduce extreme

cal research ethics committees. The mothers were randomly as- concerns about shape and weight. Guided by the therapist and

signed to the two interventions by using block randomization using the guided self-help stepwise approach, the mother was

with fixed blocks of size six, computer generated by an indepen- helped to implement the relevant steps.

dent statistician and stratified according to eating disorder diag-

nosis (bulimia nervosa or bulimic type of eating disorder not oth- Assessments

erwise specified). Allocation concealment was facilitated by using Assessments of the groups were undertaken before treatment,

sequentially numbered opaque sealed envelopes for consecutive when the infants were 4–6 months old, and after treatment when

and eligible study participants. the infants were age 13 months. The mothers and infants were

videotaped during the principal solid meal of the day. Consider-

Interventions able time was allowed to help mothers feel at ease and get used to

Thirteen 1-hour treatment sessions were offered in the moth- the camera at both assessments. If, in the mother’s opinion, the

ers’ homes beginning when the infants were between 4 and 6 posttreatment meal was not typical, a further meal was video-

months old and completed by the time the infants were 12 months taped on a separate occasion (six cases). All videotapes were rated

old. The intervention group received video-feedback interactional by independent raters blind to group assignment (including

treatment that was a modification of that developed by Juffer et al. H.W.). Investigators blind to group assignment conducted the

(9). The control group received supportive counseling. This was Eating Disorder Examination interviews and the videotaping for

chosen because it is an active, nonspecific intervention that does the assessments.

900 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 163:5, May 2006

STEIN, WOOLLEY, SENIOR, ET AL.

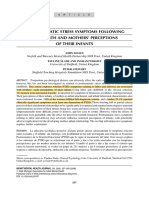

Outcomes FIGURE 1. Participant Flow in Study of Video-Feedback

Treatment for Disturbed Relationships Between Mothers

Primary outcome. The primary outcome measure was the With Bulimic Eating Disorders and Their Infants

level of conflict during the principal meal of the day, measured

every 2 minutes for the duration of the meal and averaged. Con-

flict/harmony was rated on a 1 (conflict) to 5 (harmony) scale (6), Mothers completing Eating Disorder

on which conflict was defined as a battle for control between the Examination Questionnaire (N=2,387)

mother and infant with associated infant distress, noncompli-

ance, and invariable disruption of feeding. Key ingredients of this

Evidence of significant No evidence of significant

battle for control were a refusal to allow infant self-feeding, or to disturbance in eating disturbance in eating habits

allow feeding at the infant’s own pace, and maternal concern habits and attitudes (N=504) and attitudes (N=1,883)

about messiness. Infant behaviors such as repeated food refusal

were common features of conflict. The occurrence of a significant

conflict episode during the meal formed a dichotomous co-pri- Interviewed with Eating Declined to participate (N=56)

mary outcome measure. Such conflict was judged to have oc- Disorder Examination Unable to contact (N=71)

curred if a conflict was at a severe or marked level of clinical con- (N=377)

cern (rating of 1 or 2) for any 2-minute observational period.

Secondary outcomes. A number of secondary outcomes were

Fulfilled diagnostic criteria for

assessed: bulimic eating disorder (N=110): Did not fulfill criteria for

an eating disorder (N=265)

Infant weight, standardized against population norms (17). Bulimia nervosa (N=14)

Eating disorder not otherwise Anorexia nervosa (N=2)

Other measurements of mother-infant interaction. These out- specified, bulimic type (N=96)

comes were developed from a number of sources (5, 18). For

time-sampled rating scales, measurements were made every 2

minutes for the duration of the meal and were then averaged.

First, maternal facilitation was measured on a time-sampled rat- Gave informed Declined to participate (N=21)

consent (N=84) Excluded for other reasons (N=5):

ing scale of 1–7. It was defined as any maternal behavior that as- Severe primary depressive

sists the infant in an activity in which he or she is already engaged disorder (N=2)

or seems ready to engage. Such facilitation requires that the Deafness (N=1)

mother notices what her infant is doing, or is wanting or attempt- Severe infant abnormality (N=2)

ing to do, and sensitively gauges when and how assistance or en-

couragement is needed.

The second outcome was the number of verbal responses to in- First participants

Randomly assigned (N=80)

used in pilot study (N=4)

fant cues (appropriate and inappropriate). This measure was de-

veloped from the original sensitivity measures of Ainsworth et al.

(18). A response was categorized as appropriate when the mother

verbally responded to her infant’s cue (action, facial expression, Allocated to video- Allocated to counseling

or vocalization) in a manner congruent with that cue. The re- feedback treatment (N=40) treatment (N=40)

sponse was classified as inappropriate when the mother re-

sponded verbally to her infant’s cue in an incongruent or mis- Received Lost to follow- Received Returned to

matching manner. treatment, up after receiv- treatment, full-time

The third outcome, appropriate nonverbal responses to infant completed ing treatment completed work, did

follow-up (N=2): follow-up not receive

cues, was rated on a time-sampled rating scale of 1 (poor), 2 assessment, Family went assessment, treatment,

(moderate), and 3 (good). This measured the extent to which the and included abroad (N=1) and included and lost to

mother nonverbally and congruently picked up her infant’s cues. in analysis No follow-up in analysis follow-up

(N=38) (N=1) (N=39) (N=1)

The fourth additional interaction outcome was the number of

events of maternal intrusiveness: actions that inappropriately cut

across, took over, or disrupted the infant’s activities.

Infant autonomy involving self-feeding initiatives. This was a A number of other outcomes measured at this time were not

dichotomous measure (yes/no) indicating whether the infant was part of our hypotheses and will be analyzed later and written up

allowed to self-feed with fingers or a utensil (e.g., spoon) or had separately.

access to his or her own plate of food or a joint plate.

Maternal eating disorder psychopathology, eating habits, and Statistical Analyses

attitudes. The mothers were reassessed with the Eating Disorder Data from our previous study of mothers with an eating disor-

Examination (12). Because eating disorders are associated with der showed that 59% of mother-infant pairs experienced at least

high levels of depressive symptoms, the latter were measured by one significant episode of mealtime conflict (6). In order to detect

using a validated questionnaire, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depres- an anticipated 50% reduction in the number of mother-infant

sion Scale (19). pairs experiencing such conflict, i.e., from 60% to 30% at a 5% sig-

Expectations and perceptions of treatment. The mothers’ nificance level (two-tailed) with a power of 80%, a group size of 42

expectations of treatment were assessed on a 1–5 scale. After mothers in each group was required.

treatment, maternal perceptions of treatment benefits were as- Descriptive and analytical statistical analyses were performed

sessed with an 18-item questionnaire on which each item was by using SPSS 11.0 for Windows (SPSS, Chicago) and Stata release

rated from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The ques- 7.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, Tex.). Continuous variables were

tionnaire comprised four subscales: practical issues, help with investigated for departure from normality by using the Shapiro-

eating disorder, self-esteem and feelings about self, and relation- Wilk test, and the treatment groups were compared by means of

ship with baby. two-sample t tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, as appropriate.

Am J Psychiatry 163:5, May 2006 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 901

MOTHERS WITH BULIMIC EATING DISORDERS

TABLE 1. Characteristics of Mothers With Bulimic Eating Disorders and Their Infants Before Treatment of Disturbed Rela-

tionships With Video Feedback or Counseling

Video-Feedback Group Supportive Counseling Group

Characteristic (N=40) (N=40)

N % N %

Mother married or in stable cohabitation 32 80.0 33 82.5

Mother’s ethnicity

White 28 70.0 28 70.0

Other 12 30.0 12 30.0

Social classa

Nonmanual occupation 27 67.5 24 60.0

Manual occupation 13 32.5 16 40.0

Parity

First child 20 50.0 23 57.5

Second or subsequent child 20 50.0 17 42.5

Child’s gender

Male 15 37.5 22 55.0

Female 25 62.5 18 45.0

Mean SD Mean SD

Child’s weight z scoreb 0.14 1.16 0.37 0.95

Median Range Median Range

Mother’s age (years) 31 19 to 45 29 20 to 43

Maternal interaction with infant

Instances of appropriate verbal responses to infant cues

(number per hour) 88.35 0.0 to 331.0 84.26c 20.0 to 238.1

Score on time-sampled scale for appropriate nonverbal responses

to infant cues (1=poor, 3=good) 2.65 1.00 to 3.00 2.33c 1.00 to 3.00

Maternal psychopathology

Global score on Eating Disorder Examination 3.41 1.39 to 5.37 3.03 1.33 to 4.99

Score on Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale 14.0 1 to 24 15.0c 3 to 23

N % N %

Eating disorder diagnosis

Bulimia nervosa 6 15.0 5 12.5

Eating disorder not otherwise specified, bulimic type 34 85.0 35 87.5

Probable depressive disorder (score of 13 or above on Edinburgh

Postnatal Depression Scale) 24 61.5c 24 61.5c

a In the video-feedback group five mothers had no partner, while in the counseling group two mothers had no partner. For these families, the

mother’s social class is given.

b Standardized for age and gender.

c Data were available for only 39 subjects.

For the normally distributed outcome, the child’s age- and sex- (29.2%) fulfilled the eligibility criteria. Ultimately, 80

standardized weight at age 13 months, we used linear regression women were randomly assigned to video feedback (N=40)

to estimate the direction and magnitude of the treatment effect,

or counseling (N=40). Participant flow is shown in Figure 1.

adjusting for the mother’s baseline eating disorder classification

and the child’s standardized weight at baseline. Baseline demographic characteristics and clinical pre-

For dichotomous outcomes, the groups were compared by us- sentation were well balanced across the treatment groups

ing chi-squared tests. In addition, we calculated odds ratios that (Table 1) except for indications of imbalances in infant

were adjusted for baseline eating disorder classification and base- gender and weight.

line measurement where applicable, using logistic regression.

In order to test the consistency of the outcomes assessments, For all outcome data available, statistical comparisons

the reliability on the video-coding measures was calculated for were on an intention-to-treat basis, i.e., N=38 for the video-

20% of the subjects. Interrater reliability (weighted kappa) on the feedback group and N=39 for the counseling group. There

rating scale outcome measures ranged from 0.81 to 0.87. For were no differences between the two groups in the mean

event-sampled behaviors, the percentage concordance ranged

number of sessions completed: 12.1 (SD=1.9) for the video-

from 77% to 94%. Both of these indicate good agreement.

feedback group and 11.1 (SD=3.5) for the counseling group.

Results Mother-Infant Interaction

The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire was The group that received video feedback exhibited signif-

completed by 2,387 women, of whom 504 (21.1%) scored icantly less conflict than the group that received support-

high and 377 (15.8%) agreed to be interviewed with the Eat- ive counseling, according to scores on the conflict rating

ing Disorder Examination interview. Of these 377, 110 scale (Table 2). Episodes of marked or severe conflict were

902 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 163:5, May 2006

STEIN, WOOLLEY, SENIOR, ET AL.

TABLE 2. Interactions Between Mothers With Bulimic Eating Disorders and Their Infants and Ratings of Maternal Psycho-

logical State After Treatment of Disturbed Relationships With Video Feedback or Counseling

Video-Feedback Group Supportive Counseling

(N=38) Group (N=39) Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test

Adjusted

Measure Median Range Median Range Variance p

Mealtime conflict score (1=conflict, 5=harmony) 4.67 1.71 to 5.00 3.90 1.33 to 5.00 9622.62 0.007

Maternal mealtime interaction with infant

Facilitation score (1=none, 7=maximum) 5.71 1.20 to 7.00 3.75 1.00 to 7.00 9620.59 0.02

Instances of appropriate verbal responses to

infant’s cues (events per hour) 118.4 17.2 to 316.6 108.6 29.6 to 320.6 9632.87 0.76

Score for appropriate nonverbal responses to

infant cues (1=poor, 3=good) 2.91 1.00 to 3.00 2.50 1.00 to 3.00 9256.42 0.05

Maternal psychopathology

Global score on Eating Disorder Examination 1.64 0.10 to 4.78 1.73 0.15 to 4.46 9259.12 0.56

Score on Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale 10.0 3 to 21 11.0 0 to 23 7523.62 0.82

Scores on subscales of questionnaire regarding

mother’s perception of treatment received

(1=strongly disagree, 5=strongly agree)

Practical issues 4.50 3.00 to 5.00 4.50 3.00 to 5.00 7845.39 0.83

Help with eating disorder 3.50 1.00 to 5.00 4.00 2.00 to 5.00 8004.80 0.12

Self-esteem and feelings about self 4.20 2.75 to 5.00 4.25 2.25 to 5.00 8502.14 0.41

Relationship with baby 4.00 2.50 to 5.00 2.60 1.00 to 4.75 8139.37 <0.001

observed for 23.7% of the mother-infant pairs in the Maternal Eating Disorder Psychopathology

video-feedback group and 53.8% of those in the control There were no significant differences between the

group (Table 3). The odds ratio of 0.27 corresponds to an groups in maternal eating disorder psychopathology at

estimated 73% reduction in the odds of a marked or severe follow-up (Table 2), and both groups’ scores on the Eating

conflict episode (95% CI, 27% to 90%) in the video-feed- Disorder Examination improved significantly over the

back group when compared with the control group. course of the treatment; the mean change across the

Further benefits of video feedback included the child’s groups was 1.32 points (95% CI, 1.06 to 1.57). Eleven

significantly greater autonomy during mealtimes (Table (29.7%) of 37 mothers in the video-feedback group and 12

3). There was also evidence of greater maternal facilitation (30.8%) of the 39 in the control group still fulfilled the di-

of the infants and a higher level of appropriate nonverbal agnostic criteria for an eating disorder. There were no dif-

ferences between the groups in depressive symptoms (Ta-

responses to infant cues in the video-feedback group (Ta-

ble 2), but there were overall improvements in both

ble 2). There was weaker evidence that the mothers receiv-

groups; the mean change across groups in the score on the

ing video feedback were less likely to use inappropriate

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale was 2.71 (95% CI,

verbal responses to infant cues than mothers in the con-

1.32 to 4.10).

trol group (Table 3), but there was no difference between Post hoc multiple regression analysis was used to exam-

the groups in appropriate verbal responses to cues (Table ine the influences of change in eating disorder score,

2). There was also no difference between the groups in change in depressive symptoms, and the treatment group

terms of maternal intrusiveness, with reductions in both (video feedback versus supportive counseling) on conflict

groups of around 30% (Table 3). outcome. Only the treatment group variable was signifi-

cant (multiple linear regression, t=–2.29, p=0.03).

Infant Weight

At follow-up, when the infants were 13 months old, the

Maternal Expectations and Perceptions of

Treatment

mean z scores (standardized) for infant weight were 0.11

(SD=1.10) for the video-feedback group and 0.23 (SD= There were no differences between the groups in their

0.93) for the counseling group. While we observed a slight expectations of treatment; the median scores, on a scale of

1 (not at all helpful) to 5 (very helpful), were 4 for the

imbalance at baseline favoring the counseling group (Ta-

video-feedback group (range=2–5) and 5 for the counsel-

ble 1), the mean adjusted difference in standardized infant

ing group (range=3–5) (adjusted variance=7475.35, p=

weight at 13 months was 0.03 (95% CI, –0.38 to 0.32, p=

0.67). At the end of treatment, the women in the video-

0.85); i.e., there was no significant difference between the

feedback group perceived themselves to be significantly

groups in (standardized) infant weight. more helped than the control group with their relation-

There was a nonsignificant positive correlation be- ships with their infants (Table 2), notably with “the way my

tween poorer weight gain from pretreatment to age 13 baby and I get on at mealtimes,” but there were no differ-

months and the conflict rating at 13 months (rs=0.16, N= ences between groups in scores on the other subscales.

77, p=0.16). Both groups perceived themselves to be considerably

Am J Psychiatry 163:5, May 2006 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 903

MOTHERS WITH BULIMIC EATING DISORDERS

TABLE 3. Behaviors During Mealtimes of Mothers With Bulimic Eating Disorders and Their Infants Before and After Treat-

ment of Disturbed Relationships With Video Feedback or Counseling

Odds Ratio (adjusted for

Video- Supportive baseline eating disorder

Feedback Group Counseling Group classification with logistic

(N=38) (N=39) Chi-Square Analysis regression)

Odds

Mealtime Behavior N % N % χ2 df p Ratio 95% CI

Severe or marked conflict

(posttreatment only) 9 23.7 21 53.8 7.36 1 0.007 0.27 0.10 to 0.73

Inappropriate verbal

responses to infant

cues by mother

Baseline 20 50.0a 22 56.4 — — — — —

Posttreatment 17 44.7 26 66.7 3.75 1 0.053 0.38b 0.13 to 1.07

Maternal intrusions

Baseline 17 42.5a 21 53.8 — — — — —

Posttreatment 11 28.9 15 38.5 0.78 1 0.38 0.73b 0.26 to 2.02

Infant autonomy

Baseline — — — — — — — — —

Posttreatment 34 89.5 25 64.1 6.92 1 0.009 4.75 1.39 to 16.22

a Percent was based on 40 subjects.

b Also adjusted for baseline measurement.

helped with their eating disorder and with their own feel- Both groups maintained infant weight at the end of the

ings and self-esteem. study; the mean weight of infants in each group was a little

over the population mean, and there were no differences

Discussion between the groups. Thus, although video feedback did

not lead to a significant between-group difference in in-

We found that a video-feedback treatment directed spe- fant weight, it is reassuring that there was no falloff in

cifically at mother-infant interaction led to greater im- weight in either group. While a relationship between con-

provements in outcome than did a counseling treatment flict and lower weight has previously been demonstrated

focused on the mother. In particular, the index treatment (5), in this study the association between poorer infant

was associated with less conflict, better maternal facilita-

weight gain and conflict at age 13 months was small and

tion and appropriate nonverbal responses to infant cues,

nonsignificant. Many factors influence weight gain, and

fewer inappropriate verbal responses to cues by the

this requires further investigation.

mother, and greater child autonomy during mealtimes. To

There were also no significant differences between the

our knowledge, this is the first time that a treatment in the

treatment groups in maternal intrusions or appropriate

context of postnatal psychiatric disorder has been shown

verbal responses to cues. Both groups showed consider-

to lead to key improvements in mother-child interaction

able improvement in maternal eating disorder psychopa-

in a controlled trial.

thology. There was also a high level of depressive symp-

The estimated 73% reduction in the odds of a marked or

toms at baseline, which also improved in both groups. The

severe conflict episode in the video-feedback group, com-

differences in conflict outcome were found to be due to

pared to the control group, is striking as even the lower

the specific treatment each group received, rather than

limit of the 95% confidence interval, which corresponds

to a 27% reduction, is likely to be clinically relevant. These change in either eating disorder psychopathology or de-

findings are important because of the central role of pression symptoms. Conflict was not related to infant

mealtime interaction in the mother-infant relationship weight at follow-up.

(20), especially in the context of maternal eating disorder. The strengths of this study were 1) two active treatments

Mother-infant conflict and the associated damping of in- were compared, one targeted at mother-child interaction

fant initiatives and autonomy have the potential to make and the other targeted at the mother, 2) in contrast to

mealtimes an aversive experience for the infant with last- many psychological treatment studies, the principal out-

ing negative associations around food. Such conflict is es- comes were assessed by using videotape, ensuring that the

pecially likely to occur between mothers with eating dis- raters remained blind to group status, and 3) treatment

orders and their infants, and it can be seen as an index of was carried out in the mothers’ homes, which provided

the extent to which the infant gets embroiled in the ecological validity and contributed to the low dropout

mother’s eating psychopathology. Hence, the ameliora- rate. The weaknesses of this study were 1) the relatively

tion of these parenting deficits has the potential to miti- small number of subjects, necessitating a larger study, and

gate their impact on the infant and may play a role in halt- 2) mothers in both groups received guided self-help for

ing the intergenerational transmission of this form of their eating disorder, since it is ethically problematic to

psychiatric disturbance. leave an identified disorder untreated. We were therefore

904 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 163:5, May 2006

STEIN, WOOLLEY, SENIOR, ET AL.

Patient Perspectives

A 30-year-old mother revealed a 15-year history of bulimia real turning moment was when I saw a video of him looking

nervosa. During pregnancy her symptoms improved some- at me with a smile after I had given him some food. I had no

what, as she felt there was a reason for the changes in her idea that he responded to me positively during mealtimes or

body shape. However, 3 months after the birth of the baby that he even regarded me as his mother, and it was a great

she had a relapse with loss of control over eating and re- boost. I always hated him closing his mouth and refusing

emergence of vomiting. “The most difficult part was after I food, but when we looked at the videotape the therapist

stopped breast-feeding at 3 months. I then had to start pre- helped me to see that in fact he was still swallowing the pre-

paring three meals a day and find time to sit down with vious mouthful and enjoying the taste and simply couldn’t

Adrian and patiently feed him. I simply had to get the meal- take in another mouthful. She also helped me to watch

time over as soon as possible because I found it so stressful, where he was looking, and I could see that the mealtimes

but at the same time I was worried that I would eat any food were not only a time to eat but his chance to find things out

left over, which would start a binge and end up with me vom- for himself.

iting. Things were especially difficult again at about 8 months “As far as my own eating is concerned, things have im-

when he started to try and feed himself; he refused my offers proved and I don’t vomit anymore, but it can still be a strug-

and instead put his hands in the food and clumsily put the gle at times, especially when I am stressed. However, the vid-

food to his mouth, spilling most of it onto himself. eo (together with the CBT booklet) helped me to realize that

“The video feedback helped me because it gave me the Adrian’s feeding wasn’t my feeding. So anything he put in his

chance to see what was really happening with Adrian with mouth, slung on the floor, liked or disliked, or turned his

the help of the therapist. The biggest thing was to see the head away from was about his feeding, not mine.

positive things, see what worked and believe them because I “In fact, now I can actually enjoy his mealtimes — our

then felt safe to say the things that I wasn’t okay at. The first time together.”

unable to ascertain how necessary guided self-help was in jects were diagnosed with eating disorder not otherwise

supporting video feedback in reducing conflict. specified. Strict impairment criteria ensured that only

To our knowledge, this is the first treatment trial to tar- women with clinically significant levels of disorder were

get mother-infant interaction in the context of maternal included, and the baseline scores on the Eating Disorder

eating disorders. Related studies have attempted to treat Examination were comparable to those of patients in-

mothers with postnatal depression and their infants and cluded in treatment trials for bulimia nervosa (12). It

have indicated that, while it is possible to improve mater- should be noted that although guided self-help is a rela-

nal psychological state, it is more difficult to improve sig- tively limited treatment, there was considerable improve-

nificantly the mother-child interaction and child out- ment in eating disorder psychopathology as well as in de-

come (8). While these studies used treatments to help pressive symptoms.

with mother-child interaction, they did not use video In conclusion, psychiatric disorders, including eating

feedback, which provides direct access to mother-child disorders, occur commonly among women of childbear-

interaction. This study has shown that by providing such ing age and raise the risk of adverse effects on mother-

access to mother-child interaction, this interaction can child interaction and child development. This study indi-

be improved. cates that a targeted treatment conducted in the commu-

nity in the postnatal period can have significant benefits

One of the reasons that video feedback is particularly

for mothers with eating disorders and their infants. The

suited to eating disorders, and possibly to postnatal de-

low dropout rate indicates that the treatment is both feasi-

pression, is that these disorders are characterized by a nar-

ble and acceptable to parents. If these findings are repli-

rowed focus of attention to issues germane to the disorder

cated, video feedback holds promise as a treatment for a

(body shape, weight, and eating in the case of eating disor-

range of postnatal psychiatric disorders.

ders). This in turn is likely to impair the mother’s respon-

siveness to the environment, particularly her infant’s com-

Presented in part at the 18th Biennial Meeting of the International

munication. Video-feedback treatment focuses the Society for the Study of Behavioural Development, Ghent, Belgium,

mother away from her eating preoccupations onto the in- July 11–15, 2004, and at the Marcé Society International Biennial Sci-

entific Meeting, Oxford, U.K., Sept. 23–26, 2004. Received Nov. 26,

fant. It helps her to notice and interpret her infant’s behav- 2004; revision received May 9, 2005; accepted June 20, 2005. From

ior and highlights where she can encourage her infant. the Section of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psy-

Further follow-up is necessary to ascertain whether these chiatry, University of Oxford and Warneford Hospital; the Centre for

Statistics in Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, U.K.; the Tavistock

improvements are maintained and the children’s longer- and Portman National Health Service Trust, London; and the Leopold

term outcome improved. Muller Department of Child and Family Mental Health, Royal Free

and University College Medical School, University College London.

In terms of generalizability, it should be noted that rela- Address correspondence and reprint requests to Dr. Stein, Section of

tively broad inclusion criteria were used and most sub- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Univer-

Am J Psychiatry 163:5, May 2006 ajp.psychiatryonline.org 905

MOTHERS WITH BULIMIC EATING DISORDERS

sity of Oxfo rd, War neford Hospital, O xford OX3 7J Xl, U.K.; post-partum depression, 2: impact on the mother-child rela-

alan.stein@psych.ox.ac.uk (e-mail). tionship and child outcome. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 182:420–427

Supported by Wellcome Trust grant 050892 and by funding from 9. Juffer F, Hoksbergen RAC, Riksen Walraven JM, Kohnstamm GA:

the North Central London Research Consortium for the recruitment

Early intervention in adoptive families: supporting maternal

process in primary care.

sensitive responsiveness, infant-mother attachment, and in-

The authors thank the mothers and children, health visitors, and gen-

eral practitioners for their help; A. McFadyen was a supervisor and con-

fant competence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1997; 38:1039–

ducted clinical interviews; C. McKenna conducted clinical interviews; J. 1050

Winterbottom and J. Hartley conducted video ratings; and J. Walker, D. 10. Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van Ijzendoorn MH, Juffer F: Less is

Somerville, R. Weatherall, J. Garcia, L. Murray, P. Cooper, D. Waller, E. more: meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interven-

Ward, B. Blizard, H. Doll, C. McNeil, F. Juffer, M. van IJzendoorn, M. Bak- tions in early childhood. Psychol Bull 2003; 129:195–215

ermans-Kranenburg, and S. Phillips provided additional help. 11. Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ: Assessment of eating disorders: inter-

International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number, view or self-report questionnaire? Int J Eat Disord 1994; 16:

ISRCTN95026274.

363–370

12. Fairburn CG, Cooper Z: The Eating Disorder Examination (12th

ed), in Binge Eating: Nature, Assessment, and Treatment. Ed-

References ited by Fairburn CG, Wilson GT. New York, Guilford, 1993, pp

1. Patel P, Wheatcroft R, Park RJ, Stein A: The children of mothers 317–360

with eating disorders. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev 2002; 5:1–19 13. Holden JM, Sagovsky R, Cox JL: Counselling in a general practice

2. Agras S, Hammer L, McNicholas F: A prospective study of the setting: controlled study of health visitor intervention in treat-

influence of eating-disordered mothers on their children. Int J ment of postnatal depression. Br Med J 1989; 298:223–226

Eat Disord 1999; 25:253–262 14. Carter JC, Fairburn CG: Treating binge eating problems in pri-

3. Murray L, Cooper P: Intergenerational transmission of affective mary care. Addict Behav 1995; 20:765–772

and cognitive processes associated with depression: infancy 15. Cooper PJ: Bulimia Nervosa and Binge-Eating. London, Consta-

and the preschool years, in Unipolar Depression: A Lifespan ble and Robinson, 1995

Perspective. Edited by Goodyer I. Oxford, UK, Oxford University 16. Fairburn CG: Overcoming Binge Eating. New York, Guilford,

Press, 2003, pp 17–46 1995

4. Fairburn CG, Harrison PJ: Eating disorders. Lancet 2003; 361: 17. Tanner JM, Whitehouse RH, Gairdner D, Pearson J: Growth and

407–416 Development Record. Hertford, UK, Castlemead Publications,

5. Stein A, Woolley H, Cooper SD, Fairburn CG: An observational 1987

study of mothers with eating disorders and their infants. J Child 18. Ainsworth MDS, Bell SM, Stayton DJ: Infant-mother attachment

Psychol Psychiatry 1994; 35:733–748 and social development: Socialization as a product of recipro-

6. Stein A, Woolley H, McPherson K: Conflict between mothers cal responsiveness to signals, in The Integration of a Child Into

with eating disorders and their infants during mealtimes. Br J a Social World. Edited by Richards MPM. London, Cambridge

Psychiatry 1999; 175:455–461 University Press, 1974, pp 99–135

7. Nomura Y, Wickramaratne PJ, Warner V, Mufson L, Weissman 19. Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R: Detection of postnatal depres-

MM: Family discord, parental depression, and psychopathol- sion: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depres-

ogy in offspring: ten-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc sion Scale. Br J Psychiatry 1987; 150:782–786

Psychiatry 2002; 41:402–409 20. Chatoor I, Egan J, Getson P, Menvielle E, O’Donnell R: Mother-

8. Murray L, Cooper PJ, Wilson A, Romaniuk H: Controlled trial of infant interactions in infantile anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad

the short- and long-term effect of psychological treatment of Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1988; 27:535–540

906 ajp.psychiatryonline.org Am J Psychiatry 163:5, May 2006

You might also like

- Food Allergies: a Recipe for Success at School: Information, Recommendations and Inspiration for Families and School PersonnelFrom EverandFood Allergies: a Recipe for Success at School: Information, Recommendations and Inspiration for Families and School PersonnelNo ratings yet

- Holistic Baby Acupressure System: 12 Acupressure Points for Pediatric Sleep Improvement and Wellness SupportFrom EverandHolistic Baby Acupressure System: 12 Acupressure Points for Pediatric Sleep Improvement and Wellness SupportNo ratings yet

- Neu 2014Document7 pagesNeu 2014Hải TrầnNo ratings yet

- EBP Practice 2 - N - HiscockInfantSleep08 - 2016Document9 pagesEBP Practice 2 - N - HiscockInfantSleep08 - 2016Sitti Rosdiana YahyaNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Postnatal Depression On Infant Development: Lynne MurrayDocument20 pagesThe Impact of Postnatal Depression On Infant Development: Lynne Murrayana raquelNo ratings yet

- Mothers of Undernourished Jamaican Children Have Poorer Psychosocial FunctioningDocument9 pagesMothers of Undernourished Jamaican Children Have Poorer Psychosocial FunctioningJonique TyrellNo ratings yet

- Psychosocial Factors Affecting the Association Between a Healthy Lifestyle BehaviorDocument16 pagesPsychosocial Factors Affecting the Association Between a Healthy Lifestyle BehaviorHaleluya LeulsegedNo ratings yet

- Sensibilidad y LactanciaDocument10 pagesSensibilidad y LactanciaVale ViNo ratings yet

- Effect of Couple-Based Cognitive BehaviouralDocument8 pagesEffect of Couple-Based Cognitive Behaviouralaudy saviraNo ratings yet

- Bibliotherapy For Children With Anxiety 20160609 15947 1rdn1xe With Cover Page v2 DikonversiDocument10 pagesBibliotherapy For Children With Anxiety 20160609 15947 1rdn1xe With Cover Page v2 DikonversiAyunda intan WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Article 37 Forcada 2006Document10 pagesArticle 37 Forcada 2006Naoual EL ANNASNo ratings yet

- Randomized Controlled Trial of A Primary Care-Based Child Obesity Prevention Intervention On Infant Feeding PracticesDocument9 pagesRandomized Controlled Trial of A Primary Care-Based Child Obesity Prevention Intervention On Infant Feeding PracticesSardono WidinugrohoNo ratings yet

- Jurnal AnoreksiaDocument14 pagesJurnal AnoreksiaZakiyahNo ratings yet

- McFarlane2017 Article OutcomesOfARandomizedTrialOfACDocument10 pagesMcFarlane2017 Article OutcomesOfARandomizedTrialOfACGabriel GomezNo ratings yet

- Postnatal Depression Bonding StudyDocument10 pagesPostnatal Depression Bonding StudyAlexandra MarisNo ratings yet

- Maternal Symptoms of Depression Are Related To Observations of Controlling Feeding Practices in Mothers of Young ChildrenDocument6 pagesMaternal Symptoms of Depression Are Related To Observations of Controlling Feeding Practices in Mothers of Young ChildrenCatarina C.No ratings yet

- Biopsychosocial Aspects of Functional Gastrointestinal DisordersDocument15 pagesBiopsychosocial Aspects of Functional Gastrointestinal DisordersPedro LosadaNo ratings yet

- Positive Parenting Improves Multiple AspectsDocument11 pagesPositive Parenting Improves Multiple Aspectsjuliana_farias_7No ratings yet

- 2 Pamela Douglas The Crying Baby What Approach Curr Op PedDocument7 pages2 Pamela Douglas The Crying Baby What Approach Curr Op PedSara Grillo MartinezNo ratings yet

- Literature Review No 6-7Document5 pagesLiterature Review No 6-7Syafinaz SalvatoreNo ratings yet

- The Neonatal Eating Assessment Tool: Development and Content ValidationDocument9 pagesThe Neonatal Eating Assessment Tool: Development and Content ValidationdeboraNo ratings yet

- Maternally Administered Tactile Stimulation and Later Mother-Infant InteractionsDocument9 pagesMaternally Administered Tactile Stimulation and Later Mother-Infant InteractionsAna LyaNo ratings yet

- Interaction. The Relationship Between Post-Natal Depression and Mother-ChildDocument8 pagesInteraction. The Relationship Between Post-Natal Depression and Mother-ChildAnonymous Ff9apXONo ratings yet

- Barrett 2004Document17 pagesBarrett 2004danielblancozepaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Nurture and Play A Mentalisationbased Parenting Group Intervention For Prenatally Depressed MothersDocument11 pagesEffectiveness of Nurture and Play A Mentalisationbased Parenting Group Intervention For Prenatally Depressed MothersCorina IoanaNo ratings yet

- Family Based Therapy PDFDocument4 pagesFamily Based Therapy PDFGNo ratings yet

- AlimentaciónDocument23 pagesAlimentaciónMaro LisNo ratings yet

- Weinberg y Tronick 2008 Still Face Madre Panico DepreDocument20 pagesWeinberg y Tronick 2008 Still Face Madre Panico DeprePsicóloga Pilar CuellarNo ratings yet

- Depre y Apego DesorganizadoDocument21 pagesDepre y Apego DesorganizadoMargaretNo ratings yet

- First-time Mothers' Social Support, Self-Efficacy and Postnatal DepressionDocument10 pagesFirst-time Mothers' Social Support, Self-Efficacy and Postnatal Depressionmotanul2No ratings yet

- Apego Transgeneracional y AnorexiaDocument9 pagesApego Transgeneracional y AnorexiaadriNo ratings yet

- Neumark Sztainer 2010 Family Weight Talk and Dieting HowDocument12 pagesNeumark Sztainer 2010 Family Weight Talk and Dieting HowXiloNo ratings yet

- Neumark Sztainer 2010 Family Weight Talk and Dieting HowDocument12 pagesNeumark Sztainer 2010 Family Weight Talk and Dieting HowXiloNo ratings yet

- Social Science & Medicine: Qiong Wu, Tatjana Farley, Ming CuiDocument9 pagesSocial Science & Medicine: Qiong Wu, Tatjana Farley, Ming CuiLaura Valentina Huertas SaavedraNo ratings yet

- D.B.chamberlain Prenatal StimulationDocument3 pagesD.B.chamberlain Prenatal StimulationAna TomaNo ratings yet

- Psychotherapy For Postpartum DepressionDocument14 pagesPsychotherapy For Postpartum DepressionDumitrescu Radu MihaiNo ratings yet

- Artikel 2 DheaDocument16 pagesArtikel 2 Dheadayana nopridaNo ratings yet

- Infant Mental Health Journal - 2020 - Salomonsson - Short Term Psychodynamic Infant Parent Interventions at Child HealthDocument15 pagesInfant Mental Health Journal - 2020 - Salomonsson - Short Term Psychodynamic Infant Parent Interventions at Child HealthArif Erdem KöroğluNo ratings yet

- Caracteristici Interactiune Mama-CopilDocument7 pagesCaracteristici Interactiune Mama-CopildydyantonykNo ratings yet

- Maternal Depression May Impact Breastfeeding SuccessDocument6 pagesMaternal Depression May Impact Breastfeeding SuccessYessica Vega GolerNo ratings yet

- Food Insecurity ArticleDocument9 pagesFood Insecurity ArticleJam GanacheNo ratings yet

- Resumo: Notas de Pesquisa / Research NotesDocument7 pagesResumo: Notas de Pesquisa / Research NotesJoaquim Barbosa AguardemNo ratings yet

- Assignment English Summary About Guided ImageryDocument23 pagesAssignment English Summary About Guided Imagerymufid dodyNo ratings yet

- Beneficios de La Relacion y Embarazo Revision 2012Document11 pagesBeneficios de La Relacion y Embarazo Revision 2012ogarcía_pattoNo ratings yet

- Review of Literature MAILDocument12 pagesReview of Literature MAILShebin Shebi EramangalathNo ratings yet

- Cheng Etal2007Document9 pagesCheng Etal2007eebook123456No ratings yet

- GHDocument9 pagesGHReginald JuliaNo ratings yet

- Sharkey 2015Document10 pagesSharkey 2015Juanda RaynaldiNo ratings yet

- Parenting Stress TheoryDocument9 pagesParenting Stress TheoryPija RamliNo ratings yet

- Mother-Child Interactions of Preterm ToddlersDocument6 pagesMother-Child Interactions of Preterm ToddlersRominaNo ratings yet

- Vandewalle Et Al. 2017Document8 pagesVandewalle Et Al. 2017Eliora ChristyNo ratings yet

- ASI - Anne H.salonen - Depresi PostpastumDocument11 pagesASI - Anne H.salonen - Depresi PostpastumOza ArikaNo ratings yet

- Fonagy Accepted Manuscript - Attachment RF and Trauma - IMHJ-2-25-1-20Document20 pagesFonagy Accepted Manuscript - Attachment RF and Trauma - IMHJ-2-25-1-20Dalia Angelica Loaiza MarriagaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1740144515001035 MainDocument7 pages1 s2.0 S1740144515001035 MainAngel AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- 0 - Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms Following Childbirth and Mothers Perceptions - DavisDocument18 pages0 - Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms Following Childbirth and Mothers Perceptions - DavisAnaNo ratings yet

- Articles: BackgroundDocument12 pagesArticles: BackgroundEduardo PichardoNo ratings yet

- Sdarticle 142 PDFDocument1 pageSdarticle 142 PDFRio Michelle CorralesNo ratings yet

- Journal Pediatric 3Document10 pagesJournal Pediatric 3Fluffyyy BabyyyNo ratings yet

- Grief Reactions To Perinatal Death: Exploratory Study: Ho. PitalDocument6 pagesGrief Reactions To Perinatal Death: Exploratory Study: Ho. PitalRENATA PAOLA OLATE MARINKOVICNo ratings yet

- BST + Seletividade AlimentarDocument16 pagesBST + Seletividade AlimentarVinicius MartinsNo ratings yet

- MCQ Tyba Abnormal Psychology 2020Document16 pagesMCQ Tyba Abnormal Psychology 2020phanishashidharNo ratings yet

- Slide 1-Introduction To Psychological TestingDocument26 pagesSlide 1-Introduction To Psychological TestingSundas SaikhuNo ratings yet

- JOB DESCRIPTION & PERSON SPECIFICATION - Support WorkerDocument2 pagesJOB DESCRIPTION & PERSON SPECIFICATION - Support WorkerOluwatobi AkintundeNo ratings yet

- Lap of Love Quality of Life ScaleDocument2 pagesLap of Love Quality of Life ScaleNatalia Santiago CáceresNo ratings yet

- 9436-98873-Interview 15Document9 pages9436-98873-Interview 15Sam FerutNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Psychological Studies on Personality and Character TraitsDocument15 pagesAnalysis of Psychological Studies on Personality and Character Traitsjungseong parkNo ratings yet

- The Challenges of Middle and Late AdolescenceDocument16 pagesThe Challenges of Middle and Late AdolescenceDan MakilingNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Concepts of Community Health NursingDocument47 pagesFundamental Concepts of Community Health NursingRhen LiminNo ratings yet

- Planning For A Health CareerDocument22 pagesPlanning For A Health CareerROMMEL LAGATICNo ratings yet

- NCP Risk For InjuryDocument3 pagesNCP Risk For InjuryPaolo UyNo ratings yet

- Following in Common? Student From The Health Services Management Major Asks You To Identify The Primary Characteristic of Your Managerial Position. Your Answer IsDocument6 pagesFollowing in Common? Student From The Health Services Management Major Asks You To Identify The Primary Characteristic of Your Managerial Position. Your Answer IsSachin DigitalNo ratings yet

- Debunking Myths About Trauma and MemoryDocument6 pagesDebunking Myths About Trauma and MemoryKami50% (4)

- The Effects of Jealousy and Favoritism in AcademicDocument8 pagesThe Effects of Jealousy and Favoritism in AcademicRosebel RedubladoNo ratings yet

- Family Therapy Stigmas Associated With LatinosDocument15 pagesFamily Therapy Stigmas Associated With LatinosJohnNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Health Educator 2Document5 pagesCharacteristics of Health Educator 2fatimahxxx3No ratings yet

- The Sentence Completion TestDocument6 pagesThe Sentence Completion Testabisha.angeline22No ratings yet

- Coordinated School Health Education Program111Document1 pageCoordinated School Health Education Program111Mary Joy FernandezNo ratings yet

- The Distinction Between Needs and WishesDocument40 pagesThe Distinction Between Needs and WishesOana PetrescuNo ratings yet

- Part III LESSON 3 Taking Charge of One's HealthDocument12 pagesPart III LESSON 3 Taking Charge of One's HealthMelvin Pogi138No ratings yet

- Psychological Evaluation Report SummaryDocument4 pagesPsychological Evaluation Report SummaryJan Mari MangaliliNo ratings yet

- Cover Letter - PsychologistDocument2 pagesCover Letter - PsychologistRaden Farrazka Hilmilla IndirianiNo ratings yet

- Managing Exam Stress White Swan FoundationDocument32 pagesManaging Exam Stress White Swan FoundationRishabh BajpaiNo ratings yet

- Help For The Hurting Heart WorkbookDocument24 pagesHelp For The Hurting Heart WorkbookAnu GirishNo ratings yet

- Peer Support Programs in Mental Health Nursing: Harnessing Lived Experience For Recovery' Prashant Shekhar TripathiDocument9 pagesPeer Support Programs in Mental Health Nursing: Harnessing Lived Experience For Recovery' Prashant Shekhar TripathieditorbijnrNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan On AddictionsDocument6 pagesLesson Plan On AddictionsThereza Christina Vianna Ferreira (330)No ratings yet

- Personal Hygiene Health ConceptsDocument38 pagesPersonal Hygiene Health ConceptsMaryamNo ratings yet

- Cam 16 Test 2 ListeningDocument7 pagesCam 16 Test 2 Listeningmpirnazarov772No ratings yet

- Rich - Fernandez - Mindfulness ToolkitDocument3 pagesRich - Fernandez - Mindfulness ToolkitBobNo ratings yet

- Projective Tests Scoring and Interpretation To: Thematic Apperception Tests (TAT)Document38 pagesProjective Tests Scoring and Interpretation To: Thematic Apperception Tests (TAT)Khaula AhmedNo ratings yet

- PSI Report SampleDocument26 pagesPSI Report SampleSgt Z1pL0k67% (3)