Professional Documents

Culture Documents

HAPA Investigación

Uploaded by

jimenezraquel934Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

HAPA Investigación

Uploaded by

jimenezraquel934Copyright:

Available Formats

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Volume 42, Issue 6, November-December 2019

doi: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2019.038

Psychometric Properties of the Self-efficacy Scale

for a Healthy Diet in Individuals with Obesity

Julio César Cortés-Ramírez,1 Gilda Gómez-Peresmitré,1 Romana Silvia Platas Acevedo,1 Luis Villalobos-Gallegos,2

Rodrigo Marín-Navarrete3

1

Programa de Doctorado en Psi- ABSTRACT

cología, Universidad Nacional

Autónoma de México, Facultad

Background. Self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in his or her capacity to execute certain behaviors

de Psicología, Ciudad de México,

México. and determines changes in the lifestyle of persons with chronic diseases such as obesity. There is currently no

2

Facultad de Medicina y Psicología. instrument with optimal psychometric properties measuring self-efficacy for a healthy diet. HAPA is a theoretical

Universidad Autónoma de Baja framework that can describe, explain, and predict health behavior changes and its relationship with self-efficacy,

California-Campus Tijuana. and it that is useful for the development of interventions, particularly in the area of healthy diets. Objective.

3

Unidad de Ensayos Clínicos en The purpose of this study was to develop an instrument to measure self-efficacy for a healthy diet in Mexican

Adicciones y Salud Mental, Instituto

population with obesity and the evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Self-Efficacy Scale for a Healthy

Nacional de Psiquiatría. Ciudad

de México, México. Diet (SSHD). Method. The sample included 202 participants receiving care in public obesity clinics. The SSHD

applied is a Likert-type scale developed from the Health Action Process Approach containing 45 items. Omega

Correspondence:

coefficient and Confirmatory Factor Analyses were estimated to evaluate the psychometric properties. Results.

Julio César Cortés Ramírez

Universidad Nacional Autónoma The scale has good measures of goodness of fit χ2 = 66.49; p < .001; χ2 SB/gl = 41; CFIS = .955; NFI = .893; RM-

de México. Facultad de Psicología, SEAS = .056 (95% CI [.029, .079]) and total scale reliability of ω = .896 (CI 95% [.876, .915]). Discussion and

edificio D, cubículo 11, Mezzanine. conclusion. The SSHD is a reliable, valid instrument for measuring the three types of self-efficacies proposed

Avenida Universidad 3004,

in HAPA in people with obesity who require changes to adhere to a healthier diet.

Coyoacán, Copilco Universidad,

04510, Ciudad de México, México.

Phone: +52 (55) 5622-2252. Keywords: Self-efficacy, behavior modification, obesity, healthy diet.

Email: julio.cortes.tf@gmail.com

Received: 17 July 2019

Accepted: 19 November 2019 RESUMEN

Citation:

Cortés-Ramírez, J. C., Gó- Antecedentes. La autoeficacia es la creencia en las capacidades percibidas para realizar cualquier com-

mez-Peresmitré, G., Platas Aceve- portamiento; determina cambios en el estilo de vida de personas con enfermedades crónicas como la

do, R. S., Villalobos-Gallegos, L., obesidad. Actualmente no existe un instrumento con propiedades psicométricas adecuadas que mida la

& Marín-Navarrete, R. (2019). Psy-

autoeficacia para seguir una dieta saludable. El Modelo Procesual de Acciones en Salud (HAPA, por sus

chometric Properties of the Self-ef-

ficacy Scale for a Healthy Diet in siglas en inglés) es un modelo teórico que describe, explica y predice cambios en la conducta y su relación

Individuals with Obesity. Salud con la autoeficacia, especialmente en el área de la alimentación saludable. Objetivo. Desarrollar un ins-

Mental, 42(6), 289-296. trumento que mida la autoeficacia para una alimentación saludable en población mexicana con obesidad.

DOI: 10.17711/SM.0185-3325.2019.038 Con ello se obtuvieron las propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Autoeficacia para una Alimentación

Saludable (EAAS). Método. La muestra incluyó 202 personas adultas con obesidad que se encontraban en

tratamiento para reducir su peso corporal. Se aplicó la EAAS; ésta es una Escala tipo Likert desarrollada

con base en el Modelo Procesual de Acciones en Salud (HAPA, por sus siglas en inglés) y consta de 45

reactivos. Se obtuvo la validez de constructo, se estimaron coeficiente omega y análisis factorial confirma-

torio para obtener las propiedades psicométricas. Resultados. La escala tiene buenas medidas de bondad

de ajuste χ2 = 66.49; p < .001; χ2 S-B/gl = 41; CFIS = .955; NFI = .893; RMSEAS = .056 (IC 95% [.029, .079])

y de confiabilidad de la escala total ω = .896 (IC 95% [.876, .915]). Discusión y conclusión. La EAAS es

un instrumento válido y confiable para medir los tres tipos de autoeficacia que propone el modelo HAPA en

personas con obesidad que requieren cambios en la conducta alimentaria.

Palabras clave: Autoeficacia, modificación de conducta, obesidad, dieta saludable.

Salud Mental | www.revistasaludmental.mx 289

Cortés-Ramírez et al.

INTRODUCTION the process of formation of the new behavior (Schwarzer,

2008). In the motivational phase, the advantages and dis-

Self-efficacy is a psychological construct understood as advantages of behavioral change are analyzed, together

one’s belief in one’s ability to execute a specific behavior with the damage and adverse consequences habits have had

(Bandura, 1982, 1993, 2001). Self-efficacy is closely linked on health, as well as the possible outcomes of behavior-

to mental health. It is associated with well-being, perceived al change, such as success or failure. When people expect

stress, socialization, performance, optimism, self-control, positive results in this change of lifestyle, it increases the

self-esteem, depression, and anxiety. It has been found that intention and likelihood of changing behavior. Moreover,

self-efficacy determines changes in the lifestyles of people confidence in one’s own abilities to achieve the desired

with chronic illnesses (Bonsaksen, Fagermoen, & Lerdal, goal is essential (Luszczynska et al., 2005a; Schwarzer &

2014; Bonsaksen, Lerdal, & Fagermoen, 2012). Healthy Gutiérrez-Doña, 2009).

eating is understood as the diet required to achieve a healthy The volitional phase determines whether intentions will

caloric balance and weight. It is recommended to reduce be achieved. Regulatory skills and strategies are required,

the intake of fats, sugar, and sodium, and to increase the which consist of detailed plans on how, when, and where

consumption of fruit, vegetables, pulses, whole grains, nuts, behavioral changes will take place. Moreover, strategies

and water (Organización Mundial de la Salud, 2013). The are required to cope with the difficulties in achieving the

main treatment for people with obesity is the adoption of this desired results and whether one’s initial expectations have

healthy diet, which involves a series of cognitive process- been met. This phase is crucial to maintaining healthy be-

es to adhere to this behavior. The Health Action Process haviors, because the ability to recover from relapses is test-

Approach (HAPA) has proven that self-efficacy is a con- ed (Luszczynska et al., 2005a; Schwarzer, 2008; Schwarzer

struct that explains a large part of the variance in various & Gutiérrez-Doña, 2009).

domains of behaviors associated with healthy lifestyles, According to the HAPA model, there are three types of

such as physical exercise and diet (Anderson, Winett, & self-efficacy, one which operates in the motivational phase

Wojcik, 2000, 2007; Delahanty et al., 2013; Kreausu- and two in the volitional phase: a) self-efficacy in actions

kon, Gellert, Lippke, & Schwarzer, 2012; Luszczynska, or pre-volitional refers to an optimistic belief about the re-

Gutiérrez‐Doña, & Schwarzer, 2005a; Motl et al., 2002; sults of one’s behavior; individuals with a high level in this

Parschau et al., 2013; Renner et al., 2008; Scholz, Snie- component imagine success and are more likely to start a

hotta, & Schwarzer, 2005). new behavior; b) maintenance self-efficacy is the optimistic

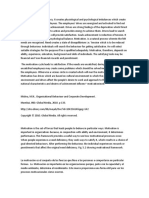

The HAPA model helps to understand the process of belief in one being able to cope with the problems that arise

adopting a healthy diet. Figure 1 distinguishes two phases when the actions have begun. Individuals with a higher lev-

in the processes of behavioral changes. The first phase is a el of this factor will invest more effort in maintaining the

motivational one, in which intentions are formed to initi- behavior despite the difficulties and barriers that occur; c)

ate a behavior and the second, called volitional, consists of self-efficacy in relapse recovery is the conviction that one

Pre-volitional Maintenance Recovery

self-efficacy self-efficacy self-efficacy

Intention Planning Start Maintenance Recovery

Process of adopting a healthy diet

Motivational phase Volitional phase

Figure 1. Process of adopting a healthy diet. Adapted from Schwarzer & Gutiérrez-Doña (2009) p. 16.

290 Salud Mental, Vol. 42, Issue 6, November-December 2019

Self-Efficacy Scale for a Healthy Diet

will be able to continue with the plans drawn up, regain siders the recommendations previously established in the

control of the situation and minimize the risks arising from literature of having at least 200 participants (Lloret-Segu-

relapses. (Renner et al., 2008; Schwarzer, 2008; Schwarzer ra, Ferreres-Traver, Hernández-Baeza, & Tomás-Marco,

& Gutiérrez-Doña, 2009). 2014; MacCallum, Widaman, Zhang, & Hong, 1999).

In recent decades, several instruments have been con-

structed to measure self-efficacy, usually on the basis of Sites

the General Self-Efficacy Scale (Luszczynska, Scholz, &

Schwarzer, 2005b). The instruments have been developed Participating patients were recruited from three public sec-

for each specific behavior, such as The Self-Efficacy for tor clinics in the metropolitan area of the Valley of Mexico,

Managing Chronic Disease Scale (Ritter & Lorig, 2014), which offer specialized treatment programs to lose body

and the Nutrition Self-Efficacy Scale/ Exercise Self-Effi- weight; these consist of diet modification, general recom-

cacy Scale (Schwarzer & Renner, 2005). In Mexico, the mendations for physical exercise, and medical supervision.

following instruments are applied Self-Efficacy for Physi-

cal Activity in School-age Children (Aedo & Ávila, 2009), Participants

Self-Efficacy for Engaging in Healthy Behaviors in Healthy

Children (Flores León, González-Celis Rangel, & Valencia The inclusion criteria for participants were men and women

Ortíz, 2010), and the Inventory of Perceived Self-Efficacy aged 18 to 65 years, with a Body Mass Index (BMI) ≥ 30, who

for Weight Control Adapted for the Mexican School Popu- were seeking nutritional treatment to reduce body weight and

lation (Saldaña, Peresmitré, Meraz, & del Castillo Arreola, were able to read and write. The exclusion criteria were being

2011). These instruments are difficult to use in the popula- candidates for bariatric surgery and attending treatment as a

tion of interest because they are mainly designed for chil- requirement for a surgical operation.

dren in a school context. At present, there is no instrument

in Mexico for measuring self-efficacy for an adult diet based Development of the instrument

on the HAPA model (Luszczynska et al., 2005b; Scholz,

Nagy, Göhner, Luszczynska, & Kliegel, 2009; Schwarzer The construction of the SSHD was based on the Schwarzer

& Renner, 2005). Nutrition Self-Efficacy Scale (Schwarzer & Renner, 2005)

Developing an instrument that makes a conceptu- with five items with four response options. The authors re-

al distinction between various self-efficacies is extremely ported a good Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency of .87

useful in health behavior research since it allows one to fo- (n = 1 726) and a r = .59 in the test-retest test (n = 982). This

cus on the type of self-efficacy that must be reinforced at scale has been developed and tested on various samples

each stage of the change, particularly because of its impact (Gutiérrez-Doña, Lippke, Renner, Kwon, & Schwarzer,

on the formation of intentions, maintenance, and recovery 2009; Renner et al., 2008; Schwarzer, 2008). To this end,

from relapses. It has been shown that self-efficacy in actions the following steps were taken:

is the best predictor of intentions, whereas self-efficacy in 1. A bank of 60 statements was constructed to en-

maintenance is the best predictor of behavior (Schwarzer, compass the dimensions of the HAPA model

2008; Schwarzer & Gutiérrez-Doña, 2009). Previous stud- (Luszczynska et al., 2005b; Scholz et al., 2009;

ies have found a significant association between self-effica- Schwarzer & Gutiérrez-Doña, 2009; Zhou et al.,

cy in actions and maintenance and scores and the adoption 2013): pre-volitional self-efficacy (18 items),

of healthy foods (Hromi-Fiedler et al., 2016; Zhang et al., maintenance self-efficacy (22 items), and self-ef-

2018; Zhou, Gan, Knoll, & Schwarzer, 2013). The high- ficacy for relapse recovery (20 items).

er the score in these two types of self-efficacy, the greater 2. The qualitative technique of cognitive laboratories

the decrease in body weight (Hattar, Pal, & Hagger, 2016). was used (Johnstone, Bottsford-Miller, & Thomp-

Self-efficacy in relapse recovery is related to both the in- son, 2006; Zucker, Sassman, & Case, 2004) to

tention of making changes in behavior and to an increase culturally adapt the statements and make them

in physical exercise in people with obesity (Luszczynska et understandable for the Mexican population. The

al., 2005a; Schwarzer & Gutiérrez-Doña, 2009). participants were people with obesity who had

been in treatment to reduce body weight, male and

female with an age range of 24 to 60 years, whose

METHOD educational attainment ranged from middle school

to undergraduate degree level. Based on their feed-

Study design back, sentences or words that were not understood

were modified.

This is a descriptive, analytical, multicenter cross-section- 3. An evaluation was conducted by judges to obtain

al study with a convenience sample design, which con- the validity of the content of the instrument. Judges

Salud Mental, Vol. 42, Issue 6, November-December 2019 291

Cortés-Ramírez et al.

were chosen based on the criteria of: (a) experience the data set failed to meet the assumption of multivariate

in making judgments and decision-making based normality, the maximum likelihood estimation with robust

on evidence or expertise (such as degrees, research, standard errors and a mean and variance adjusted test sta-

publications, position, experience, and awards), (b) tistic (MLMV) was used. Since the estimator uses scaling

reputation in the community, (c) availability and measures, the goodness of fit measures considered were Sa-

motivation to participate, (d) impartiality and in- torra and Bentler’s chi-square (χ2S-B), the scaled comparative

herent qualities such as self-confidence and adapt- adjustment index (CFIS ≥ .95), and the Root Mean Square

ability (Skjong & Wentworth, 2000). The judges Error of Approximation (RMSEAS ≤ .05). The regression

numerically rated each of the 60 items on a scale of coefficients, standard errors, and statistical significance for

one to four, in addition to making suggestions about each parameter estimated in the model are given. In addi-

the wording of the items, which were then modified. tion, the internal consistency of each factor and of the total

Items that obtained a degree of agreement of less scale was evaluated with the coefficient of reliability of the

than 80% were eliminated, in other words, those compounds (ω). To this end, the recommendations estab-

that obtained an average of less than 3.5 of all the lished in the literature were used (Raykov & Marcoulides,

judges’ evaluations (Appendix 1). 2011). The CFA and the estimation of the reliability coeffi-

cients were carried out using Mplus 8 software.

Measurements

Ethical considerations

The instrument applied to the sample was made up by 45

Likert items comprising the SSHD, with three dimensions The study was approved by a research and ethics commit-

of self-efficacy: pre-volitional, maintenance, and relapse tee, all patients gave their informed consent and interna-

recovery. Each dimension contains 15 items. Each item tionally established guidelines for the protection of human

contains six response options ranging from Totally Agree research participants were followed.

to Totally Disagree.

Procedure RESULTS

1. The SSHD was applied to 300 participants, on the Participants had a BMI > 30 (range 30 to 42) and an average

assumption that 30% of the applications might age of M = 46.3 (SD = 11.9) with a range of 27 to 65 years.

have missing data. Patients who were at different Table 1 describes the sociodemographic characteristics of

stages of treatment were included and a database the sample.

with 202 questionnaires was developed.

2. Construct validity was tested by exploratory factor

analysis (EFA). Table 1

3. Items showing collinearity were eliminated, based Characteristics of participants

on modification indices and ensuring that the item n %

removed did not affect the measurement of an im- Sex

portant dimension of the construct according to the Men 57 28.2

theory. Women 145 72.8

4. Lastly, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was Occupation

performed. Housewife 76 37.6

Employee 52 25.7

Statistical analysis Shopkeeper 34 16.8

Other 40 19.9

Descriptive statistics were used for the analysis of socio- Educational attainment

demographic data. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) Did not answer 26 12.9

was applied to find a model with a good fit and contrast it Elementary 9 4.5

with the theoretical proposal of the Health Actions Process Middle school 71 35.1

Approach. This analysis was performed with SPSS 23. The High school 47 23.3

method employed was Main Components with VARIMAX Technical degree 27 13.4

rotation, and the significant contribution criterion of more University 19 9.4

than .4 was used to consider that the item corresponded to a Master’s degree 3 1.5

factor. To confirm the structure obtained by the EFA, a con- SD

firmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed. Because Age 46.3 11.9

292 Salud Mental, Vol. 42, Issue 6, November-December 2019

Self-Efficacy Scale for a Healthy Diet

Exploratory factor analysis

r3 .498 (.061)

Forty-five items were analyzed, yielding a three-compo- 1.000 (.000)

r6 .553 (.118)

nent solution that explains 41.1% of the variance. Table 2 1.079 (.134)

.402 (.072) f1

reports the 27 items with factor loads of over .40, while .934 (.161) r10 .966 (.169)

items 2, 8, 13, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 22, 25, 26, 29, 31, 1.185 (.171)

32, 33, 38, and 42 had a lower load. Component 1, labeled r36 .684 (.191)

“Pre-volitional Self-efficacy (PS),” grouped together 10 .155 (0.59)

r39 .944 (.187)

items corresponding to the belief in one’s capacity to initi-

ate behaviors related to healthy eating. Component 2, called 1.000 (.000)

r40 1.412 (.216)

“Maintenance self-efficacy (MS),” grouped together eight .487(.070)

.764 (.194) f2

.921 (.162)

1.574 (.229)

items that measured the belief in the ability to maintain a r45 .259 (.169)

.814 (.174)

healthy diet, even when barriers or difficulties began to be

observed. Lastly, component 3, called “Self-efficacy for -.014 (.112) r24 1.415 (.174)

relapse recovery (SRR),” included nine items measuring

r11 1.018 (.245)

beliefs in the ability to resume healthy eating following a

1.000 (.000)

suspension or relapse. 1.360 (.235) 1.257 (.224)

f3 .743 (.099) r12

.747 (.118)

r30 1.154 (.177)

Table 2 Figure 2. Model selected for the CFA.

Factor loads obtained in the exploratory analysis for the

solution of three factors

Factor Confirmatory factor analysis

Item 1 2 3

37 .65 .03 .21 The CFA tested the 27 items with a factor load of at least .40.

34 .60 .12 .24 Items with high modification rates were eliminated follow-

10 .60 .01 .16 ing the recommendations to avoid collinearity (Byrne, 2010)

36 .59 .22 .33 and taking into account their theoretical importance (Kline,

6 .56 .14 .18 2011).

3 .55 .13 .24 The following items were eliminated: factor one 37,

1 .54 .16 .09 34, 25, 21, 9, and 1, factor two 44, 43, 41, 35, 28, and 23,

21 .53 .12 .07 factor three 27, 14, 7, 5, and 4.

25 .52 -.12 .07 After evaluating the model, the following measures of

9 .52 -.05 .12 goodness of fit χ2 = 66.49, p < .001, and χ2 S-B/gl = 41 were

45 .05 .91 -.05 obtained. CFIS = .955, NFI = .893, RMSEAS = .056 (95%

41 .07 .69 .09 CI [.029, .079]). The coefficients, standard errors and z val-

39 .15 .66 .08 ues of the items comprising the final version of the CFA are

40 -.09 .59 .04 shown in Figure 2. Factor one comprised items 3, 6, 10,

44 .07 .58 .21 and 36; factor two items 24, 39, 40, and 45; and factor three

24 .08 .57 -.02 items 11, 12 and 30. As regards internal consistency, the

28 -.02 .54 -.04 reliability coefficients of the compounds were: AP ω = .724

43 .17 .54 .14 (CI 95% [.655, .793]); AM ω = .779 (CI 95% [.655, .793]);

23 .02 .48 .32 ARR ω = .711 (CI 95% [.628, .794]); total scale ω = .896

35 .23 .40 .31 (CI 95% [.876, .915]).

14 .12 .14 .75

11 .22 .01 .73

7 .19 .02 .69 DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

5 .18 .29 .64

12 .24 -.03 .53 Measuring self-efficacy in the population with obesity pos-

27 .37 .10 .51 es a challenge for research. The development of this scale

4 .11 .22 .50 was based on the need to measure self-efficacy as regards

30 .34 -.02 .47 diet in a population with obesity. Schwarzer’s Self-effica-

Eigen Values 3.85 4.04 3.63 cy Scale for Nutrition (Schwarzer & Renner, 2005), which

Salud Mental, Vol. 42, Issue 6, November-December 2019 293

Cortés-Ramírez et al.

we used as a base, contains five items. We consider that important that they feel effective in overcoming the barriers

we could cover other aspects of self-efficacy by increasing and difficulties that come along with changes in food.

the number of items for each dimension of the construct. It was found that factors two and three are correlated,

These include the perception of support from one’s partner as observed in the results, while the third factor only com-

or family, criticism for being on a diet, the time and money prised three items corresponding to maintenance self-effi-

spent preparing food, frustration in response to unsuccess- cacy. This may be because once people start a healthy diet,

ful attempts, and being able to resist non-nutritious foods in they perceive relapses as part of the barriers to maintaining

poorly-controlled environments such as parties, etc. behavioral change rather than an independent difficulty. Re-

The evaluation of psychological constructs during the cent studies have found that this type of self-efficacy pre-

initial, maintenance, and recovery from relapses stages re- dicts positive results in weight loss. Measurement of this

quires the use of instruments that consider the sociocul- factor is essential, once actions have been initiated, since in-

tural context. It was therefore necessary to consider the dividuals with a higher level of perceived self-efficacy will

way patients understand the construct of self-efficacy and persist more and invest more effort in maintaining the new

not only the definition. Accordingly, time and resources behavior (Schwarzer, 2008; Schwarzer & Gutiérrez-Doña,

were spent on constructing statements that were clear 2009; Schwarzer & Renner, 2005).

enough to assess the patient’s beliefs in their own abil- Limitations of the study include the fact that it is a

ities in relation to healthy eating, the axis of treatment non-probabilistic sample, which makes it impossible to

for reducing body weight. Although the HAPA model generalize the results obtained through the sample to the

(Schwarzer & Gutiérrez-Doña, 2009; Schwarzer & Ren- population from which it was extracted, and the fact that

ner, 2005) has been translated into Spanish and used in data collection was based on self-reporting. An additional

the Latino population, as a result of analyzing the items limitation is related to the use of the same sample to per-

it contains, we consider that the Spanish translation is form EFA and CFA, even though this is a practice used

insufficient. Mexicans may observe different barriers and in similar studies. This makes it impossible to determine

obstacles from the populations that have been researched. whether the resulting model is strictly generalizable within

Another reason for creating a new instrument was that some the population or to other populations.

studies used four and seven response options interchange- Although several articles on self-efficacy scales

ably. In short, we believe we could obtain greater validity based on the HAPA model show internal consistency data

by systematically conducting the development of the instru- (Luszczynska et al., 2005b; Schwarzer & Gutiérrez-Doña,

ment (based on the HAPA model) from preparing the items 2009; Schwarzer & Renner, 2005), since no studies were

to obtaining psychometric properties. To this end, cognitive found reporting the assessment of the factor structure of the

laboratories were conducted to adapt it culturally. Content instruments they use, the findings of this research contrib-

validity was obtained through expert judges, and construct ute empirical evidence to the HAPA model. It is a Spanish

validity through EFA and CFA to obtain the Self-efficacy instrument, based on this model, which measures the three

Scale for a Healthy Diet (SSHD). The results obtained show types of self-efficacy and has confirmatory factor analysis.

a three-factor SSHD model with an adequate fit. SSHD could be useful for evaluating the self-efficacy

The factor structure of the SSHD coincides with the of people with obesity who begin treatment to reduce body

three types of self-efficacy proposed by the Health Ac- weight, since self-efficacy is related to changes in diet such

tions Process Approach (Schwarzer, 2008; Schwarzer & as the consumption of fruits and vegetables (Hromi-Fiedler

Gutiérrez-Doña, 2009; Schwarzer et al., 2007). The first et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2013). High scores increase the

factor, called “Prevolitional Self-efficacy,” is very import- chances of success in treatment, in addition to the fact that

ant for beginning the changes in the diet required to reduce the instrument could provide important information for fo-

body weight in obesity treatment. This type of self-efficacy cusing psychological interventions on this group of patients,

is the best predictor of the intention to make a change since if they have low self-efficacy, they have a high proba-

in one’s diet (Anderson et al., 2000; Anderson, Konz, bility of dropping out of treatment or being unsuccessful in

Frederich, & Wood, 2001; Delahanty et al., 2013). Ac- their attempts to lose weight.

curately measuring this construct makes it possible to

Funding

distinguish between people who are prepared to begin

treatment from those who need to develop their intention During the undertaking of the study and the development of the

and increase their self-efficacy. The second factor is called manuscript, JCCR received funding from the Consejo Nacion-

“Self-efficacy for relapse recovery.” It has been found that al de la Ciencia y Tecnología (CONACyT) through a doctor-

al study grant (grant number 165002). CONACyT was not in-

people who consider relapses a total failure are less likely to

volved in the design, conceptualization or study data collection,

continue treatment, unlike those who perceive themselves the development of the manuscript, or the decision to submit it

as capable of recovering. The third factor was called “Main- for publication.

tenance Self-efficacy.” Once people begin treatment, it is

294 Salud Mental, Vol. 42, Issue 6, November-December 2019

Self-Efficacy Scale for a Healthy Diet

Conflicts of interest Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 8(1), 127-151. doi: 10.1111/

aphw.12065

The authors declare they have no conflict of interest. Hromi-Fiedler, A., Chapman, D., Segura-Pérez, S., Damio, G., Clark, P., Martinez,

J., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2016). Barriers and facilitators to improve fruit and

Contributions

vegetable intake among WIC-eligible pregnant Latinas: An application of the

JCCR and GLPM designed the study, coordinated the data collec- health action process approach framework. Journal of Nutrition Education and

tion and, together with LVG, drafted the manuscript and conduct- Behavior, 48(7), 468-477. doi: 10.1016/J.JNEB.2016.04.398

ed the statistical analyses. SRPA and RMN participated through a Johnstone, C. J. Bottsford-Miller, N. A., & Thompson. S. J. (2006). Using the

critical review of the manuscript. All the authors have approved think aloud method (cognitive labs) to evaluate test design for students with

the final version of the article. disabilities and english language learners. Technical report 44. National Center

on Educational Outcomes, University of Minnesota. Retrieved from https://eric.

Acknowledgements ed.gov/?id=ED495909

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling

Thanks are due to all the study participants, authorities, doctors,

(Second). New York: Guilford Press.

and nutritionists at the obesity clinics who supported the undertak- Kreausukon, P., Gellert, P., Lippke, S., & Schwarzer, R. (2012). Planning and self-

ing of this research. efficacy can increase fruit and vegetable consumption: a randomized controlled

trial. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 35(4), 443-451. doi: 10.1007/s10865-

REFERENCES 011-9373-1

Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernández-Baeza, A., & Tomás-Marco,

Aedo, Á., & Ávila, H. (2009). Nuevo cuestionario para evaluar la autoeficacia I. (2014). El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica,

hacia la actividad física en niños. Revista Panamericana de Salud Publica, revisada y actualizada. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 1151-1169. doi: 10.6018/

26(4), 324-329. Retrieved from https://www.scielosp.org/article/ssm/content/ analesps.30.3.199361

raw/?resource_ssm_path=/media/assets/rpsp/v26n4/v26n4a06.pdf Luszczynska, A., Gutiérrez‐Doña, B., & Schwarzer, R. (2005a). General

Anderson, E. S., Winett, R. A., & Wojcik, J. R. (2000). Social-cognitive determinants self‐efficacy in various domains of human functioning: Evidence from

of nutrition behavior among supermarket food shoppers: A structural equation five countries. International Journal of Psychology, 40(2), 80-89. doi:

analysis. Health Psychology, 19(5), 479-486. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.5.479 10.1080/00207590444000041

Anderson, E. S., Winett, R. A., & Wojcik, J. R. (2007). Self-regulation, self-efficacy, Luszczynska, A., Scholz, U., & Schwarzer, R. (2005b). The general self-efficacy

outcome expectations, and social support: Social cognitive theory and nutrition scale: multicultural validation studies. The Journal of Psychology, 139(5), 439-

behavior. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 34(3), 304-312. doi: 10.1007/ 457. doi: 10.3200/JRLP.139.5.439-457

BF02874555 MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size

Anderson, J. W., Konz, E. C., Frederich, R. C., & Wood, C. L. (2001). Long-term in factor analysis. Psychological Methods, 4(1), 84-99. doi: 10.1037/1082-

weight-loss maintenance: a meta-analysis of US studies. The American Journal 989X.4.1.84

of Clinical Nutrition, 74(5), 579-584. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/74.5.579 Motl, R. W., Dishman, R. K., Saunders, R. P., Dowda, M., Felton, G., Ward, D. S.,

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American & Pate, R. R. (2002). Examining social-cognitive determinants of intention

Psychologist, 37(2), 122-147. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122 and physical activity among black and white adolescent girls using structural

Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. equation modeling. Health Psychology, 21(5), 459-467. doi: 10.1037/0278-

Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117-148. doi: 10.1207/s15326985ep2802_3 6133.21.5.459. PMID: 12211513

Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review Organización Mundial de la Salud. (2013). OMS | Dieta. Retrieved September 12,

of Psychology, 52(1), 1-26. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 2019, from https://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/diet/es/

Bonsaksen, T., Fagermoen, M. S., & Lerdal, A. (2014). Trajectories of self-efficacy in Parschau, L., Fleig, L., Koring, M., Lange, D., Knoll, N., Schwarzer, R., & Lippke,

persons with chronic illness: An explorative longitudinal study. Psychology & S. (2013). Positive experience, self-efficacy, and action control predict physical

Health, 29(3), 350-364. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2013.856432 activity changes: A moderated mediation analysis. British Journal of Health

Bonsaksen, T., Lerdal, A., & Fagermoen, M. S. (2012). Factors associated with self- Psychology, 18(2), 395-406. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02099.x

efficacy in persons with chronic illness. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology. Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2011). Introduction to psychometric theory.

53(4), 333-339. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00959.x Routledge.

Byrne, B. (2010). Structural equation modeling with Amos: Basic concepts, Renner, B., Kwon, S., Yang, B.-H., Paik, K.-C., Kim, S. H., Roh, S., ... Schwarzer, R.

applications, and programming (2nd. ed). New York: Taylor and Francis Group, (2008). Social-cognitive predictors of dietary behaviors in South Korean men

LLC. and women. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 15(1), 4-13. doi:

Delahanty, L. M., Peyrot, M., Shrader, P. J., Williamson, D. A., Meigs, J. B., & 10.1007/BF03003068

Nathan, D. M. (2013). Pretreatment, psychological, and behavioral predictors Ritter, P. L., & Lorig, K. (2014). The English and Spanish self-efficacy to manage

of weight outcomes among lifestyle intervention participants in the Diabetes chronic disease scale measures were validated using multiple studies.

Prevention Program (DPP). Diabetes Care, 36(1), 34-40. doi: 10.2337/dc12- Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(11), 1265-1273. doi: 10.1016/j.

0733 jclinepi.2014.06.009

Flores León, A., González-Celis Rangel, A. L., & Valencia Ortíz, A. (2010). Saldaña, R. M. E. G., Peresmitré, G. G., Meraz, M. G., & del Castillo Arreola,

Validación del instrumento de autoeficacia para realizar conductas saludables A. (2011). Análisis factorial confirmatorio del inventario de autoeficacia

en niños Mexicanos sanos. Psicología y Salud, 20(1), 23-30. doi: 10.25009/pys. percibida para control de peso en población mexicana. Psicología

v20i1.613. Retrieved from http://psicologiaysalud.uv.mx/index.php/psicysalud/ Iberoamericana, 19(2), 78-88. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/

article/view/613 comocitar.oa?id=133921440009

Gutiérrez-Doña, B., Lippke, S., Renner, B., Kwon, S., & Schwarzer, R. (2009). Scholz, U., Nagy, G., Göhner, W., Luszczynska, A., & Kliegel, M. (2009).

Self‐efficacy and planning predict dietary behaviors in Costa Rican and Changes in self-regulatory cognitions as predictors of changes in smoking

South Korean women: Two moderated mediation analyses. Applied and nutrition behaviour. Psychology & Health, 24(5), 545-561. doi:

Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 1(1), 91-104. doi: 10.1111/j.1758- 10.1080/08870440801902519

0854.2009.01004.x Scholz, U., Sniehotta, F. F., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). Predicting physical exercise in

Hattar, A., Pal, S., & Hagger, M. S. (2016). Predicting physical activity-related cardiac rehabilitation: The role of phase-specific self-efficacy beliefs. Journal

outcomes in overweight and obese adults: A health action process approach. of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 27(2), 135-151. doi: 10.1123/jsep.27.2.135

Salud Mental, Vol. 42, Issue 6, November-December 2019 295

Cortés-Ramírez et al.

Schwarzer, R. (2008). Modeling health behavior change: How to predict and modify physical activity. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 33(2), 156-166. doi: 10.1007/

the adoption and maintenance of health behaviors. Applied Psychology, 57(1), BF02879897

1-29. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2007.00325.x Skjong, R., & Wentworth, B. (2000). Expert judgement and risk perception. Retrieved

Schwarzer, R., & Gutiérrez-Doña, B. (2009). Modelando el cambio en el from http://research.dnv.com/skj/Papers/SkjWen.pdf

comportamiento de salud: Cómo predecir y modifcar la adopción y el Zhang, C., Zheng, X., Huang, H., Su, C., Zhao, H., Yang, H., ... Pan, X. (2018). A

mantenimiento de comportamientos de salud. Revista Costarricense de study on the applicability of the health action process approach to the dietary

Psicología, 28(41-42), 11-39. Retrieved from https://www.redalyc.org/ behavior of university students in Shanxi, China. Journal of Nutrition Education

pdf/4767/476748706011.pdf and Behavior, 50(4), 388-395. doi: 10.1016/J.JNEB.2017.09.024

Schwarzer, R., & Renner, B. (2005). Health-specific self-efficacy scales. Retrieved Zhou, G., Gan, Y., Knoll, N., & Schwarzer, R. (2013). Proactive coping moderates

April 5, 2018, from http://userpage.fu-berlin.de/~health/healself.pdf the dietary intention–planning–behavior path. Appetite, 70, 127-133. doi:

Schwarzer, R., Schüz, B., Ziegelmann, J. P., Lippke, S., Luszczynska, A., & Scholz, 10.1016/J.APPET.2013.06.097

U. (2007). Adoption and maintenance of four health behaviors: Theory-guided Zucker, S., Sassman, C., & Case, B. J. (2004). Cognitive Labs. Retrieved from http://

longitudinal studies on dental flossing, seat belt use, dietary behavior, and images.pearsonassessments.com/images/tmrs/tmrs_rg/CognitiveLabs.pdf

APPENDIX 1

11 reactivos finales

1. Sé que puedo empezar a comer sanamente.

2. Sé que puedo tomar más agua al día.

3. Estoy convencido/a que puedo evitar alimentos poco saludables (grasas, azúcares, salado, refrescos, etc.).

4. Estoy convencido/a que puedo comer más frutas y verduras cada día.

5. Estoy convencido/a que puedo comer alimentos nutritivos incluso si tengo poco tiempo para prepararlos y comerlos.

6. Estoy convencido/a que puedo tener una alimentación saludable solo si estoy relajado.

7. Estoy convencido/a que puedo tener una alimentación saludable incluso si algunos días fallara en mis intentos.

8. Estoy convencido/a que podría tener una alimentación saludable incluso si me criticaran por estar a dieta.

9. Dudo que podría retomar una alimentación saludable si fallara en algunas ocasiones.

10. Dudo que podría retomar una alimentación saludable si durante unos días comiera alimentos poco saludables.

11. Dudo que podría retomar una alimentación saludable si perdiera el control de lo que como.

296 Salud Mental, Vol. 42, Issue 6, November-December 2019

You might also like

- The Non-Diet Approach Guidebook for Dietitians (2013): A how-to guide for applying the Non-Diet Approach to Individualised Dietetic CounsellingFrom EverandThe Non-Diet Approach Guidebook for Dietitians (2013): A how-to guide for applying the Non-Diet Approach to Individualised Dietetic CounsellingNo ratings yet

- Recent Research in Nutrition and Growth: 89th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Dubai, March 2017From EverandRecent Research in Nutrition and Growth: 89th Nestlé Nutrition Institute Workshop, Dubai, March 2017No ratings yet

- An Overview of Conceptualizations of Eating Disorder Recovery, Recent Findings, and Future DirectionsDocument18 pagesAn Overview of Conceptualizations of Eating Disorder Recovery, Recent Findings, and Future DirectionsGuerrero NataliaNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Knowledge, Beliefs and Behaviours in Teenage School StudentsDocument18 pagesNutritional Knowledge, Beliefs and Behaviours in Teenage School Studentsshikha82No ratings yet

- Framson 2009 MEQDocument6 pagesFramson 2009 MEQJanine KoxNo ratings yet

- Nola J. Pender: Health Promotion ModelDocument32 pagesNola J. Pender: Health Promotion ModelConDr UyNo ratings yet

- The Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control QuestionnaireDocument28 pagesThe Healthy Lifestyle and Personal Control QuestionnaireDon Chiaw Manongdo50% (2)

- 2019 Moderation of Mood in The Transfer of Self Regulation FromDocument6 pages2019 Moderation of Mood in The Transfer of Self Regulation FromLina M GarciaNo ratings yet

- 1471 2458 14 995 PDFDocument10 pages1471 2458 14 995 PDFSIRIUS RTNo ratings yet

- Deci Ryan Teoria Auto DeterminariiDocument24 pagesDeci Ryan Teoria Auto DeterminariiAndreeaEne100% (1)

- Nutritional Assessment and Its Comparison Between Obese and NonDocument37 pagesNutritional Assessment and Its Comparison Between Obese and NonJaspreet SinghNo ratings yet

- 5bCTCP - 638 5dDocument7 pages5bCTCP - 638 5dBNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review On The Kap-O Framework For Diabetes Education and ResearchDocument21 pagesA Systematic Review On The Kap-O Framework For Diabetes Education and ResearchToyour EternityNo ratings yet

- The Benefits of Willpower Research EssayDocument6 pagesThe Benefits of Willpower Research Essayapi-355828098No ratings yet

- T2D Patient Impowerment PDFDocument11 pagesT2D Patient Impowerment PDFRafikNo ratings yet

- Impact of Non-Diet Approaches On Attitu... D Health Outcomes - A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesImpact of Non-Diet Approaches On Attitu... D Health Outcomes - A Systematic ReviewJes BakerNo ratings yet

- Psychological Aspects of Weight Maintenance and Relapse in ObesityDocument8 pagesPsychological Aspects of Weight Maintenance and Relapse in ObesitylauraNo ratings yet

- 10 Psych Interventions 2 v7 With Links 1Document16 pages10 Psych Interventions 2 v7 With Links 1Aditza AdaNo ratings yet

- PosterDocument1 pagePosterapi-242376719No ratings yet

- Aarr - Jul.2017Document27 pagesAarr - Jul.2017hidememeNo ratings yet

- Article 1Document7 pagesArticle 1dguginNo ratings yet

- 6 Garaulet y Col, 2012Document8 pages6 Garaulet y Col, 2012Valentina NarettoNo ratings yet

- ComprehensiveLifestyleInterventionImprovesHairSkin Townsend 08octDocument9 pagesComprehensiveLifestyleInterventionImprovesHairSkin Townsend 08octCee VeeNo ratings yet

- Nutrition Education and Counselling Behavioral Change: Trans Theoretical Model/StagesDocument3 pagesNutrition Education and Counselling Behavioral Change: Trans Theoretical Model/StagesMarielle Chua50% (2)

- Appi Ps 201400535 PDFDocument6 pagesAppi Ps 201400535 PDFArif IrpanNo ratings yet

- Poster Session: Professional Skills/Nutrition Assessment/Medical Nutrition TherapyDocument1 pagePoster Session: Professional Skills/Nutrition Assessment/Medical Nutrition TherapyRandom guyNo ratings yet

- Assessment Tools in ObesityDocument39 pagesAssessment Tools in ObesityPatricio GGNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Nutritional Status - IDocument12 pagesAssessment of Nutritional Status - ITamilarasan Arasur100% (1)

- Psychosocial Effects of A Holistic Ayurvedic Approach To Well-Being in Health and Wellness CoursesDocument9 pagesPsychosocial Effects of A Holistic Ayurvedic Approach To Well-Being in Health and Wellness CoursesFranciscoNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Behavioral TheoryDocument3 pagesCognitive Behavioral TheoryLyzajoyce SeriozaNo ratings yet

- Articulo 15 CorrectoDocument12 pagesArticulo 15 CorrectoKarol Lizeth Paz ZuñigaNo ratings yet

- Emagrecimento Determinantes ShowwwwDocument41 pagesEmagrecimento Determinantes ShowwwwÉomer LanNo ratings yet

- 4 Coaching para El Tratamiento de La 2021Document12 pages4 Coaching para El Tratamiento de La 2021Vital SaludNo ratings yet

- HMB Weight ManagementDocument5 pagesHMB Weight ManagementJesse M. MassieNo ratings yet

- Aplicación Universidad de AarhusDocument21 pagesAplicación Universidad de AarhusFrancisca Cabezas HenríquezNo ratings yet

- Hartmann Boyce2018Document21 pagesHartmann Boyce2018danie.arti01No ratings yet

- Kindness Based MeditationDocument46 pagesKindness Based MeditationAlvinNo ratings yet

- Guertin2017 PDFDocument14 pagesGuertin2017 PDFmonicaNo ratings yet

- Self Efficacy in Health Promotion Research and Practice Conceptualization and MeasurementDocument15 pagesSelf Efficacy in Health Promotion Research and Practice Conceptualization and MeasurementriskhawatiNo ratings yet

- Bacon - Size Acceptance and IntuitIve Eating - JADA.05Document8 pagesBacon - Size Acceptance and IntuitIve Eating - JADA.05Evelyn Tribole, MS, RD100% (2)

- Physician Resilience What It Means, Why It.12Document3 pagesPhysician Resilience What It Means, Why It.12Fernando Miguel López DomínguezNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Saud Siddiqi - LRDocument32 pagesMuhammad Saud Siddiqi - LRwasif ahmedNo ratings yet

- 2011 BSQValidacioDocument11 pages2011 BSQValidacioAnonymous 4LIXFKUNo ratings yet

- Cockerham and ColleaguesDocument14 pagesCockerham and ColleaguesMubarak AbdullahiNo ratings yet

- SREBQ ValidacionDocument11 pagesSREBQ ValidacionJoem cNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Nursing PracticeDocument40 pagesFundamentals of Nursing PracticeLendell Kelly B. YtacNo ratings yet

- Vasquez L Nurs310-RealageDocument11 pagesVasquez L Nurs310-Realageapi-240028260No ratings yet

- Introductory ConceptsDocument52 pagesIntroductory ConceptsShamaica SurigaoNo ratings yet

- Determinant of Health - Related Behaviours Theorical and Methodological IssuesDocument37 pagesDeterminant of Health - Related Behaviours Theorical and Methodological IssuesFaris AbsorNo ratings yet

- Biopsychosocial Model of HealthDocument10 pagesBiopsychosocial Model of HealthDavin DoNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Canadian Nursing Concepts Process and Practice Canadian 3rd Edition Kozier Solutions Manual DownloadDocument9 pagesFundamentals of Canadian Nursing Concepts Process and Practice Canadian 3rd Edition Kozier Solutions Manual DownloadEarl Blevins100% (21)

- 02 OriginalDocument7 pages02 Originaljose zapataNo ratings yet

- 2 s2.0 S1499404623005237 MainDocument13 pages2 s2.0 S1499404623005237 MaingerenteosieoNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Framework of Nola J. Pender 2Document4 pagesTheoretical Framework of Nola J. Pender 2almazan_jeizelNo ratings yet

- Body Image Change and Improved Eating Self-Regulation in A Weight Management Intervention in WomenDocument11 pagesBody Image Change and Improved Eating Self-Regulation in A Weight Management Intervention in WomenAnca RaduNo ratings yet

- Self EfficacyDocument33 pagesSelf EfficacyAziz Januariawan100% (1)

- Patient-Reported Outcomes of Ayurveda Consultation in Relation To Clinical Practice DataDocument9 pagesPatient-Reported Outcomes of Ayurveda Consultation in Relation To Clinical Practice DataInfinit13No ratings yet

- Mindfulness-Based Interventions For Binge Eating: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument15 pagesMindfulness-Based Interventions For Binge Eating: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisAntonia LarisaNo ratings yet

- CHN LNW EbjDocument3 pagesCHN LNW EbjJacovNo ratings yet

- Oops! It Looks Like You're in The Wrong AisleDocument15 pagesOops! It Looks Like You're in The Wrong AisleJassilah Tuazon TabaoNo ratings yet

- 5.mpob - MotivationDocument11 pages5.mpob - MotivationChaitanya PillalaNo ratings yet

- Reliability (Statistics)Document7 pagesReliability (Statistics)Anuj KumarNo ratings yet

- 抗壓性格量表之編製及信度、效度的建立Document30 pages抗壓性格量表之編製及信度、效度的建立Sam Chi ChiNo ratings yet

- Pengembangan Tes RIASECDocument16 pagesPengembangan Tes RIASECwandanugraha013No ratings yet

- Unang Arifin,+1598 Siska+Febriyani+97-104Document8 pagesUnang Arifin,+1598 Siska+Febriyani+97-1044491 Tarisa Veronika PutriNo ratings yet

- Classical Conditioning WorksheetDocument3 pagesClassical Conditioning WorksheetJessieNo ratings yet

- 15. ინტელექტიDocument38 pages15. ინტელექტიLizy BegashviliNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5Document27 pagesChapter 5Charity Laurente BurerosNo ratings yet

- MPS - DiagnosticDocument10 pagesMPS - DiagnosticPatzAlzateParaguyaNo ratings yet

- Differences Between Classical and Operant Conditioning Classical Conditioning Operant ConditioningDocument6 pagesDifferences Between Classical and Operant Conditioning Classical Conditioning Operant ConditioningSyed Ali Huzaifah BukhariNo ratings yet

- ReliabilityDocument9 pagesReliabilityFareena BaladiNo ratings yet

- Case Questions Growing ManagersDocument1 pageCase Questions Growing ManagersGia AbbasiNo ratings yet

- Cronch Bach Alpha Test RealiabilityDocument6 pagesCronch Bach Alpha Test Realiabilityzaka4decNo ratings yet

- Classical ConditioningDocument1 pageClassical ConditioningMary Blair AdaNo ratings yet

- MotivationDocument169 pagesMotivationmagarwal22No ratings yet

- PR2 Lesson3Document25 pagesPR2 Lesson3Celestial LacambraNo ratings yet

- Validation Academic Integrity SurveyDocument19 pagesValidation Academic Integrity SurveySilviux AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Motivating Summary From Roberto Medina BookDocument3 pagesMotivating Summary From Roberto Medina BookZandra LlorenNo ratings yet

- The Scenario TestDocument16 pagesThe Scenario TestAnonymous PersonNo ratings yet

- A221 SGDE4013 8 Validity&Validation VNBDocument97 pagesA221 SGDE4013 8 Validity&Validation VNBArif HilmiNo ratings yet

- Basic Motivation ConceptsDocument31 pagesBasic Motivation Conceptssourav kumar rayNo ratings yet

- Motivational TheoriesDocument18 pagesMotivational Theoriesguruprasadmbahr100% (2)

- 2541 7063 1 PBDocument12 pages2541 7063 1 PBAdyan NugrahaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Basic Motivation Concepts Multiple ChoiceDocument26 pagesChapter 6 Basic Motivation Concepts Multiple ChoiceMandeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Teorias de La Motivacion 2Document4 pagesTeorias de La Motivacion 2renovpNo ratings yet

- A Classification of Motivation TheoriesDocument5 pagesA Classification of Motivation TheoriesEloisa Cara100% (1)

- Chapter 5 Perception Ans SensationDocument4 pagesChapter 5 Perception Ans SensationPing Ping TanNo ratings yet

- T NG ÔN - Chap 8 MotivationDocument8 pagesT NG ÔN - Chap 8 MotivationVương AnhNo ratings yet

- Motivation - Human BehaviourDocument11 pagesMotivation - Human BehaviourRamlalNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument25 pages1 PBDesi HemavianaNo ratings yet