Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Mole DTree

Uploaded by

qs6mj69ztzOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Mole DTree

Uploaded by

qs6mj69ztzCopyright:

Available Formats

The CEO of a firm in a highly competitive industry believes that one

of her key employees is providing confidential information to the

competition….

The “Mole” 10/25/2002 page 1 of 9

The chief executive officer of a firm in a highly competitive industry believes

that one of her key employees is providing confidential information to the

competition.

She is 90% certain that this informer is the vice-president of finance, whose

contacts have been extremely valuable in obtaining financing for the

company.

• If she decides to fire this VP and he is the informer, she estimates that the

company will gain $500,000.

• If she decides to fire this VP but he is not the informer, the company will

lose his expertise and still have an informer within the staff—the CEO

estimates that this outcome would cost her company about $2.5 million!

• If she decides not to fire this VP, she estimates that the firm will lose $1.5

million whether or not he is actually the informer (since in either case the

informer is still with the company).

The “Mole” 10/25/2002 page 2 of 9

Before deciding whether to fire the VP for finance, the CEO could order lie

detector tests.

To avoid possible lawsuits, the lie detector tests would have to be administered

to all company employees, at a total cost of $150,000.

Another problem she must consider is that the available lie detector tests are not

perfectly reliable:

• the probability of a false positive is 15%

• the probability of a false negative is 5%.

That is, since here “positive” means detecting a lie,

• if a person is not lying, the test will incorrectly suggest that the person is

lying 15% of the time.

• if a person is lying, the test will incorrectly suggest that the person is

telling the truth 5% of the time.

The “Mole” 10/25/2002 page 3 of 9

In order to minimize the expected total cost of managing this difficult

situation, what strategy should the CEO adopt?

Also, determine the maximum amount of money that the CEO should be willing

to pay to administer lie detector tests.

The “Mole” 10/25/2002 page 4 of 9

The posterior probabilities need to be

computed using Bayes’ Rule:

“States of nature”:

• VP is mole

• VP not mole

“Observations of experiment”:

• positive (he is lying)

• negative (he is truthful)

For example:

P{VP is Mole & +}P{VP is Mole}

P{VP is Mole | +} =

P{+}

The “Mole” 10/25/2002 page 5 of 9

Computation of posterior probabilities

P{+ | VP is Mole}P{VP is Mole}

P{VP is Mole | +} =

P{+}

(0.95) ( 0.9 )

=

0.87

0.855

=

0.87

= 0.9828

where

P {+} = P{+ | VP is Mole}P{VP is Mole} + P{+ | VP not Mole}P{VP not Mole}

= (0.95) ( 0.9 ) + ( 0.15 )( 0.1)

= 0.87

The “Mole” 10/25/2002 page 6 of 9

Computation of posterior probabilities

P{− | VP is Mole}P{VP is Mole}

P{VP is Mole | −} =

P{−}

(0.05) ( 0.9 )

=

0.13

0.045

=

0.13

= 0.3462

We can now insert these probabilities in the decision tree and “fold it

back”…

The “Mole” 10/25/2002 page 7 of 9

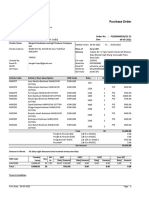

The “Mole” 10/25/2002 page 8 of 9

0.9828

VP=mole

0.35

Fire VP 0 0.35

0 0.2984 0.0172

0.87 VP#mole

Test positive -2.65

1 0 -2.7

0 0.2984

Keep VP

-1.65

0 -1.65

Do testing

0.3462

0 0.05 VP=mole

0.35

Fire VP 0 0.35

0 -1.6114 0.6538

0.13 VP≠mole

Test negative -2.65

1 0 -2.7

0 -1.6114

2 Keep VP

0.2 -1.65

0 -1.65

0.9

VP=mole

0.5

Fire VP 0 0.5

0 0.2 0.1

VP≠mole

Don't test -2.5

1 -2.5

0 0.2

Keep VP

-1.5

0 -1.5

The optimal strategy is not to administer the lie detector test,

but to fire the VP!

The “Mole” 10/25/2002

You might also like

- Blankie Owl Crochet Pattern Sol MaldonadoDocument24 pagesBlankie Owl Crochet Pattern Sol Maldonadonatys100% (1)

- An Introduction To Debt Policy and Value - Syndicate 4Document9 pagesAn Introduction To Debt Policy and Value - Syndicate 4Henni RahmanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13-Investments in Noncurrent Operating Assets-Utilization & Re-TirementDocument26 pagesChapter 13-Investments in Noncurrent Operating Assets-Utilization & Re-Tirement수지No ratings yet

- Night AuditDocument16 pagesNight AuditKumarasamy Vijayarajan100% (1)

- FINA 6216 Report - Data Case 5Document5 pagesFINA 6216 Report - Data Case 5Ahtsham AhmadNo ratings yet

- QAMDocument10 pagesQAMRavi Krishna IIM, CalcuttaNo ratings yet

- Presentation SkillDocument107 pagesPresentation SkillClarita BangunNo ratings yet

- Determining The Optimal Level of Product AvailabilityDocument75 pagesDetermining The Optimal Level of Product AvailabilityTakarial l0% (1)

- VaR I PDFDocument84 pagesVaR I PDFSunil ShettyNo ratings yet

- 10 Masiclat V CentenoDocument2 pages10 Masiclat V CentenoAgus DiazNo ratings yet

- Normal Approximation To BinomialDocument5 pagesNormal Approximation To Binomialatom108No ratings yet

- Tutorial-1 2012 Mba 680 Solutions1Document5 pagesTutorial-1 2012 Mba 680 Solutions1Pratheek MedipallyNo ratings yet

- Session 4 ADocument15 pagesSession 4 AAashishNo ratings yet

- 9.8.1 Conditional Probability and Bayes Theorem Filled inDocument4 pages9.8.1 Conditional Probability and Bayes Theorem Filled inMaría Dolores YepesNo ratings yet

- Experimental Verification of Principle of Superposition For An Indeterminate StructureDocument10 pagesExperimental Verification of Principle of Superposition For An Indeterminate StructureRupinder SinghNo ratings yet

- Group 07 F 207 ExcelDocument146 pagesGroup 07 F 207 ExcelMd. Safiqul IslamNo ratings yet

- Investment Decisions pt.4Document15 pagesInvestment Decisions pt.4sastaambani1No ratings yet

- Session 7: OutlineDocument50 pagesSession 7: Outlinejohn.nstatNo ratings yet

- Econometric Assignment 1Document6 pagesEconometric Assignment 1Citra WiduriNo ratings yet

- Cailin Chen Question 9: (10 Points)Document5 pagesCailin Chen Question 9: (10 Points)Manuel BoahenNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 - SupportDocument15 pagesChapter 5 - SupportwafarasoolNo ratings yet

- Fofport 1Document8 pagesFofport 1AliceNo ratings yet

- Tata CommunicationDocument5 pagesTata CommunicationkmmohammedroshanNo ratings yet

- Add Employees No Change in Headcount Lay Off Employees: Workforce PlanDocument8 pagesAdd Employees No Change in Headcount Lay Off Employees: Workforce PlanSravan SridharNo ratings yet

- Modeling Risk and Realities Week 4 Session 1Document45 pagesModeling Risk and Realities Week 4 Session 1Abdul MuksithNo ratings yet

- JK2e Ch005 SM March 2017Document30 pagesJK2e Ch005 SM March 2017Sakshi AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Credit-Scoring-CASEDocument29 pagesCredit-Scoring-CASEreach2ghoshNo ratings yet

- Phase 6 - Solve Problems by Applying The Algorithms of Unit 3Document19 pagesPhase 6 - Solve Problems by Applying The Algorithms of Unit 3Mariajose MariajoseNo ratings yet

- Zgjidhje Ushtrime InvaDocument6 pagesZgjidhje Ushtrime InvainvaNo ratings yet

- 29 LuhPutuNadiaTrisnaDewi UTSDocument13 pages29 LuhPutuNadiaTrisnaDewi UTSNadiatrisnaaNo ratings yet

- Điều khiển sử dụng đại số gia tửDocument15 pagesĐiều khiển sử dụng đại số gia tửLinh LêNo ratings yet

- Project 23Document212 pagesProject 23Dakun PonorogoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 05 Net Present Value and Other Investment Rules PDFDocument35 pagesChapter 05 Net Present Value and Other Investment Rules PDFWan Maulana AkbarNo ratings yet

- Central CompositeDocument9 pagesCentral CompositenormalNo ratings yet

- Practice Sheet 3Document182 pagesPractice Sheet 3Peuli DasNo ratings yet

- Rio Rifaldo-Mc Cabe DestilasiDocument12 pagesRio Rifaldo-Mc Cabe DestilasiSerly MarcellinaNo ratings yet

- Net Present Value and Other Investment Rules: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinDocument32 pagesNet Present Value and Other Investment Rules: Mcgraw-Hill/IrwinASAD ULLAHNo ratings yet

- Assignment 1Document2 pagesAssignment 1SwapnilNo ratings yet

- Econometrics Assignment 3Document4 pagesEconometrics Assignment 3Pedro FernandezNo ratings yet

- Beautiful Dashboard For Brand AnalysisDocument16 pagesBeautiful Dashboard For Brand AnalysisEdmonNo ratings yet

- CQF January 2023 M1L1 BlankDocument52 pagesCQF January 2023 M1L1 BlankAntonio Cifuentes GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Capital Budgeting With Risk MGMTDocument15 pagesCapital Budgeting With Risk MGMTAmit JainNo ratings yet

- MBA 2007 06 Investment Decisions (1) 13-11 AMDocument21 pagesMBA 2007 06 Investment Decisions (1) 13-11 AMPiyush ShetiyaNo ratings yet

- Module10-Hypothesis Testing and Statistical Tools (Business)Document18 pagesModule10-Hypothesis Testing and Statistical Tools (Business)CIELICA BURCANo ratings yet

- Practice Sheet 3 - ExtraDocument202 pagesPractice Sheet 3 - ExtraPeuli DasNo ratings yet

- FM09-CH 05Document4 pagesFM09-CH 05Mukul KadyanNo ratings yet

- Project Report: A Study On Financial Planning and Forecasting in Honda Motorcompany LimitedDocument11 pagesProject Report: A Study On Financial Planning and Forecasting in Honda Motorcompany LimitedArpita GuptaNo ratings yet

- Decision-Making Using Probability: 6.1 Expected Monetary ValueDocument8 pagesDecision-Making Using Probability: 6.1 Expected Monetary ValueJaya sankarNo ratings yet

- M5 - Risk and ReturnDocument76 pagesM5 - Risk and ReturnZergaia WPNo ratings yet

- CF 10e Chapter 11 Excel Master StudentDocument32 pagesCF 10e Chapter 11 Excel Master StudentWalter CostaNo ratings yet

- Internal Rate of ReturnDocument7 pagesInternal Rate of Returniram juttNo ratings yet

- Heriot-Watt University Finance - June 2021 Section I Case StudiesDocument8 pagesHeriot-Watt University Finance - June 2021 Section I Case StudiesSijan PokharelNo ratings yet

- MSCI570 - Lecture 8 - Advanced Regression Analysis 2022 Part 2Document26 pagesMSCI570 - Lecture 8 - Advanced Regression Analysis 2022 Part 2Việt Trịnh ĐứcNo ratings yet

- A Small Note On MM Theory and APVDocument4 pagesA Small Note On MM Theory and APVChristopherLalbiakniaNo ratings yet

- Failure Reporting Made Simple ISO 14224 ML STD 2155 ASDocument25 pagesFailure Reporting Made Simple ISO 14224 ML STD 2155 ASEduardoNo ratings yet

- LIH BLOSR6x166 ENDocument2 pagesLIH BLOSR6x166 ENDr.Nouf alhasawiNo ratings yet

- Areas and Quantiles of The Normal Distribution: Mean Standard DeviationDocument6 pagesAreas and Quantiles of The Normal Distribution: Mean Standard DeviationMaryBrujitaNo ratings yet

- Time Value Money ProblemsDocument6 pagesTime Value Money ProblemsWendell Markus Peliño SabulberoNo ratings yet

- NPV, Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and The Profitability Index (PI)Document24 pagesNPV, Internal Rate of Return (IRR), and The Profitability Index (PI)Sumbul JavedNo ratings yet

- Potentiometric TitrationDocument4 pagesPotentiometric Titrationfrankbrown11956No ratings yet

- Simple$MultipleLinearRegression RobinTeotiaDocument15 pagesSimple$MultipleLinearRegression RobinTeotiahani.sharma324No ratings yet

- Portfolio Assignment: InstructionsDocument9 pagesPortfolio Assignment: InstructionsAntariksh ShahwalNo ratings yet

- Q4-M2 Investment RiskDocument41 pagesQ4-M2 Investment RisktaebearNo ratings yet

- Topics in Supply Chain Management Session 1: Fouad El OuardighiDocument43 pagesTopics in Supply Chain Management Session 1: Fouad El OuardighiGuNo ratings yet

- Life-Cycle Costing: Using Activity-Based Costing and Monte Carlo Methods to Manage Future Costs and RisksFrom EverandLife-Cycle Costing: Using Activity-Based Costing and Monte Carlo Methods to Manage Future Costs and RisksNo ratings yet

- WAGGGS Governance StructureDocument2 pagesWAGGGS Governance StructureHARNINI ASMANNo ratings yet

- Stability StrategyDocument4 pagesStability StrategyButtercupNo ratings yet

- Real Estate Economics in PakistanDocument3 pagesReal Estate Economics in PakistanAli AkhtarNo ratings yet

- 13.marginal Costing and Break Even AnalysisDocument17 pages13.marginal Costing and Break Even Analysissivasundaram anushanNo ratings yet

- Airport Transfer Booking Form: D D M M Y Y Y YDocument1 pageAirport Transfer Booking Form: D D M M Y Y Y YPankaj PoudyalNo ratings yet

- Philippine Manpower and Equipment Productivity RateDocument10 pagesPhilippine Manpower and Equipment Productivity RateRonald Klint Marquinez AlcarazNo ratings yet

- Eco 301Document7 pagesEco 301nhidiepnguyet08112004No ratings yet

- Bargarh Handloom and Agro Producer CompanyDocument2 pagesBargarh Handloom and Agro Producer CompanyOrmas OdishaNo ratings yet

- 2001 Econ. Paper 1 (Original)Document7 pages2001 Econ. Paper 1 (Original)peter wongNo ratings yet

- Strathern - Women in BetweenDocument392 pagesStrathern - Women in BetweenHelô SouzaNo ratings yet

- Association For Survey - v2Document4 pagesAssociation For Survey - v2sanjay chandwaniNo ratings yet

- 06 CloudbanksDocument4 pages06 CloudbankslowtarhkNo ratings yet

- Child Labour Within The Framework of Economic Development in CameroonDocument18 pagesChild Labour Within The Framework of Economic Development in CameroonMbua NyanshiNo ratings yet

- Common Mistakes of Students To Financial Activities: FL - Erudition Free Webinar by Abm 12Document38 pagesCommon Mistakes of Students To Financial Activities: FL - Erudition Free Webinar by Abm 12Larisha Frixie M. DanlagNo ratings yet

- A Proposed Mactan Amusement Park: Analee Borres QuiapoDocument1 pageA Proposed Mactan Amusement Park: Analee Borres Quiapofppalawan plansNo ratings yet

- Prajwal TradesDocument392 pagesPrajwal TradesSaheb ChakrobortyNo ratings yet

- Shuttle Service StarlightDocument7 pagesShuttle Service Starlightfs.tevengcvpNo ratings yet

- Auction Properties 16-06-2022Document115 pagesAuction Properties 16-06-2022Ramana ReddyNo ratings yet

- 3010182428unit Run Canteen (Urc) Manual PDFDocument206 pages3010182428unit Run Canteen (Urc) Manual PDFShyam Prabhu50% (2)

- Sectoral and Regional Analysis of The Ethiopian Investment ScenarioDocument69 pagesSectoral and Regional Analysis of The Ethiopian Investment Scenariokassahun meseleNo ratings yet

- Hazel Bumanglag Salomon: Employment HistoryDocument1 pageHazel Bumanglag Salomon: Employment HistoryJOEFRAN ENRIQUEZNo ratings yet

- BWN TicketDocument3 pagesBWN TicketSOUMMYA KARMAKARNo ratings yet

- BillDocument1 pageBillLan NhiNo ratings yet

- DataSheet 06042022051050Document2 pagesDataSheet 06042022051050dassourjya2.0No ratings yet