Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Use of Songs in Teaching Foreign Languages

Uploaded by

Eva VillegasCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Use of Songs in Teaching Foreign Languages

Uploaded by

Eva VillegasCopyright:

Available Formats

The Use of Songs in Teaching Foreign Languages

Author(s): Yukiko S. Jolly

Source: The Modern Language Journal , Jan. - Feb., 1975, Vol. 59, No. 1/2 (Jan. - Feb.,

1975), pp. 11-14

Published by: Wiley on behalf of the National Federation of Modern Language Teachers

Associations

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/325440

REFERENCES

Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article:

https://www.jstor.org/stable/325440?seq=1&cid=pdf-

reference#references_tab_contents

You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

National Federation of Modern Language Teachers Associations and Wiley are collaborating with

JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Modern Language Journal

This content downloaded from

78.30.14.150 on Tue, 23 Jan 2024 10:44:16 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SONGS IN TEACHING FOREIGN LANGUAGES 11

REFERENCES

the

the vocational

vocationalapplication

application

of language

of language

skillsskills

to to

Adler, Kurt, Phonetics and Diction in Singing:

a

a specific

specificfield

fieldofof

interest,

interest,

students

students

quickly

quickly

lost lost

Italian, French, Spanish, German. Minneapolis:

the

the negative

negative attitude

attitudeso common

so common among amongnon- non-

University of Minnesota Press, 1967. 161 p.

language

languagemajors.

majors.ByByeliciting

eliciting

their

their

suggestions

suggestions

Belisle, John Michael. A Study of Some Factors In-

and

and ideas

ideasinin

terms

terms of of

teaching

teaching

techniques

techniques

fluencingwe

Diction we

in Singing. (Typrewritten ms.

succeeded

succeededinin giving

giving

themtheman active Bloomington,

an active

role role

in the in Indiana),

the 1965. 239 p.

Coffin, Berton. Phonetic Readings of Songs and Arias.

development

development ofof

the

the

course.

course.

Boulder, Colorado: Pruett Press, 1964. 361 p.

Thus,

Thus,by bydeveloping

developing an an

essentially

essentially

practical

Halliday, practical

John R. Diction for Singers. Provo, Utah:

"service"

"service"course

coursefor

for

voice

voice

students,

students,

the Depart-

the Depart-

Brigham Young University Press, 1968.

ment

mentof ofFrench

French and

and

Italian

Italian

explored

explored

innova-

Marshall, innova-

Madeleine. The Singer's Manual of English

tive

tive teaching

teachingtechniques

techniqueswhich

which

maymayDiction.

well wellNew prove

prove York: G. Schirmer, 1953. 198 p.

useful in other areas and learned to deal Pfautsch, Lloyd. English Diction for Singers. New

York: Lawson-Gould Music Publishers, 1971.

with pronunciation problems which

149 do

p. not

usually occur in standard correctiveTrusler,

phonetics

Ivan. Functional Lessons in Singing. Engle-

courses. wood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1960. 134 p.

The Use of Songs in Teaching

Foreign Languages

YUKIKO S. JOLLY, University of Hawaii

I. Relationship Between Language and Music

the

the "speech"

"speech"of

ofa agiven

givenlanguage

language

ends

ends

and

and

thethe

"song"

"song" categorization

categorizationbegins.

begins.One

Oneethnomusi-

ethnomusi-

cologist

cologist has

IT HAS BEEN a longtime desire of mine to hasattempted

attemptedthis,

this,but

buteven

even

hishis

proposal

proposal

leaves

leaves an

explore more extensively the potential benefits an imprecise

imprecise"grey

"greyarea"

area"

between

between

thethe

which can be derived from the systematic and two

two and

and is

is inapplicable

inapplicabletotocertain

certaincultures.'

cultures.'

TheThe

theoretical

theoretical

careful utilization of songs in the teaching of a comparison

comparison of

ofsongs

songstoto

speech

speechshould

should

foreign language. During the past three yearsperhaps

perhaps

I be

be left

leftforformore

moredetailed

detaileddiscussion

discussion

in in

have had the opportunity of teaching begin- other

other papers.

papers. It

It should

should be

besufficient

sufficient forfor

ourour

ning and intermediate Japanese (conversation) purpose

purpose here

here to

to recognize

recognize briefly

brieflythe

thepoints

points

of of

similarity

similarity as

courses in which I have been able to use Japanese asaatheoretical

theoreticaljustification

justification

forfor

thethe

useuse

of

songs as supplements to long established lessons, songs

songs inin language

language teaching.

teaching.

and have found the results of my limited experi- AtAt the

the risk

risk of

ofoversimplification,

oversimplification, wewemight

might

ence in this area to have been most rewarding. Iconsider

consider songs

songs as

asrepresenting

representing "distortions"

"distortions" of of

the

the normal

feel that language teachers may be missing a great normal speech

speechpatterns

patternsofofa language.

a language.ThisThis

deal by not exploiting songs and other rhythmic is not

not to

to imply

implyanything

anythingderogatory,

derogatory, but

but

to to

rec-rec-

language compositions as classroom teachingognize

ognize that

that songs

songsand

andnormal

normal speech

speech

areare

on on

thethe

aids. same

same continuum

continuumof ofvocally-produced

vocally-produced human

human

sounds.

sounds. Both

The close relationship between language and Bothhave

haverhythmic

rhythmic and

andmelodic

melodiccon-

con-

music is an easily recognizable one. Both entitiestent,

tent, and

and represent

representforms

formsofof

communication

communicationin in

have significant common elements and similari- a linguistic

linguistic sense.

sense.

ties. Songs might be looked upon as occupying In simplified

simplifiedgraphic

graphicform,

form,wewe

might

might

consider

consider

the middle ground between the disciplines of a linear

linear scale

scaledepicting

depictingeveryday

everyday "speech"

"speech"

pat-

pat-

terns at the left-side of a horizontal line with

linguistics and musicology, possessing both the

communicative aspect of language and the en- increasing degrees of "distortion" or "affected-

tertainment aspect of music. Indeed it may be1George List, "The Boundaries of Speech and

an impossible task to describe the point at which

Song," Ethnomusicology, Vol. 7, 1963, pp. 1-16

This content downloaded from

78.30.14.150 on Tue, 23 Jan 2024 10:44:16 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12 YUKIKO S. JOLLY

ness" toward the right. Moving along this imagi-

Studies in the relationship between language

nary line, we would have "heightened speech"and the rhythmic and tonal elements of music

(such as in political speeches, sermons, or have

dra-been conducted in a number of countries

matic exaggerations) first in line as we moved

besides the United States.4 A recent article by

to the right; next, "dramatic speech" (such as

Professor Sadanori Bekku of Sophia University

in Japanese kabuki or noh plays); "chant"discusses

or the rhythmic structure of the Japanese

"auctioneering" further along; and finally

language.' Professor Bekku states that the Japa-

"songs" on the far right.2 This is admittedly nese language is based on a rhythmic structure

not a perfect analogy, for the definitionof ofa 5-7 syllabic sequence, such as is found in

"song" itself will vary from culture to culture. the formalized forms of haiku and tanka poems."

Yet it should be sufficient to illustrate our basic As we gain more insight into the rhythmic

emphasis: songs, although quantitatively differ- elements of language through these various

ent from normal speech in terms of amounts of studies, it becomes more apparent that songs

"distortion" present, are qualitatively similarhave a more important and sophisticated place

linguistically and therefore represent valid ma- in language teaching than we have previously

terial for study within the broad framework of accorded them. More than providing a welcome

language learning. Songs not only represent respite from the tedium of everyday language

material for study, but represent a "method"drills, songs may be used to teach specific lan-

of language study within themselves. guage elements. The balance of this paper at-

A further point of theoretical justificationtempts to point out some of the uses of songs as

relating to the use of songs in foreign language they relate to the foreign language teaching

education might be found in the inherent rhyth- situation.

mic nature of life itself. The everyday routines

of our culture are obvious reflections of manyII. Implications for Classroom Pedagogy

varied rhythmic patterns, so it is not strange Let us consider the use of songs in a foreign

that our language is also rhythmically con-language classroom where vocabularies and

trolled. An intriguing research experiment con- grammar are carefully chosen in response to

ducted by two medical doctors in Boston indi-the students' level of mastery. There would

cated that babies respond to and are influencedappear to be little doubt regarding the effective-

by the rhythmic patterns of the language spokenness of songs in raising or at least maintaining

to them.3 Through a frame-by-frame study of

sound films taken of infants (some only 12 hours *Ibid., p. 3.

:'William S. Condon and Louis W. Sander, "Neo-

old) while they were being spoken to by an

nate Movement Is Synchronized with Adult Speech:

adult, the doctors were able to establish that Interactional Participation and Language Acquisition,"

the babies' movements became synchronized Science, January 11, 1974, pp. 99-101.

with the rhythm of the speech patterns used by 4For instance, Nicolas Ruwet, "Les Methodes

d'analyse en musicologie," Liber Amicorum Andre

the adult speaker. This response by the listener

Souris (Revue beige de musicologie, 18), 1966. A

to the speaker's speech pattern has been termed translation is available in Japanese, "Ongakugaku to

"interactional synchrony." The authors of theGengogaku," Gengo, Vol. 2, No. 5, 1973, pp. 354-

above report emphasize that infants move in361 and 491 by Kazuko Inoue of International Christian

precise, shared rhythms in response to the or-University, Tokyo.

ganized speech structure of their culture (per- 5Sadanori, Bekku, "Yonby-shi Bunka-ron," Gengo

Seikatsu, No. 265, October, 1973, pp. 31-39.

haps thousands of times) before they actually 'If the reader wishes to see the close relationship

use them in speaking the language. The study between 5-7 syllabic sequence and the quarter-time

also indicates the important influence and value rhythmic pattern, use the following examples and

recite them to a 4-4 time beat accompaniment:

that rhythm has in language acquisition. This

Haiku example:

innate responsiveness to the rhythm in the

Asagao ni/tsurube torarete/morai-mizu/.

speech patterns of a culture's language may have Tanka or Waka example:

valuable pedagogical implications in our lan- Okuyama ni/momiji fumiwake/naku shika no/

guage teaching methods. Koe kiku toki zo/aki wa kanashiki/.

This content downloaded from

78.30.14.150 on Tue, 23 Jan 2024 10:44:16 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

SONGS IN TEACHING FOREIGN LANGUAGES 13

the students' motivation in such a situation. If reinforcing course features, such as those dis-

the songs are presented along with atten-cussed below.

tion-catching, colorful visual aids to further (1) Pronunciation

strengthen their value, the effectiveness of the It would seem to be a basic postulate that the

songs as teaching aids can be enhanced evennative or folk songs of a given culture naturally

further. The students' response to the use offollow or reflect the basic meter, pitch, dynamics

songs under these circumstances would notor other phonological elements and patterns of

represent mere mechanical, drill-style repetition,its language. Music is written to complement

but rather active participation in the pleasant the lyric or vice-versa. Trying to match English

flow of melody. words with a native Chinese tune may be an

In Japanese conversation courses taught byextremely difficult task since the latter is in-

the author, appropriate songs were adopted fortended for a tonal language of different meter

use in classes consisting of 15 to 20 students per and dynamics. The result would probably sound

section. These songs were selected in accordance unnatural to a listener-even those who did not

with the objectives of the lesson, season of theunderstand either language.

year (as related to Japanese culture), holidays, On the other hand, Japanese lyrics seem to be

and other lesson criteria. Seeking to more ac-more easily fitted to Western music because the

curately assess the value of songs as teaching language structure is more adaptable. The basic

aids in the classroom, special class evaluationsdifference between the phonological elements-

were requested at the end of each semester. especially the element of accent-of the English

The students were asked to rate songs (along and the Japanese languages is that the former

with other class activities) according to theiris stress-timed while the latter is syllable-timed.

usefulness on a scale of 1 to 5 (ranking fromThe Japanese syllables are short (composed of

"not useful" to "very useful"'). When songsusually a vowel or a consonant-vowel cluster)

were used as lesson supplements during two and approximately equal in length for each

successive semesters, a significant majority ofmoraic utterance, and they therefore provide a

the students rated the songs as being "veryconvenient unit for the application to a musical

useful" (80% and 91% respectively) with the note. The syllable-timed language seems to al-

1 to 5 rating never dropping below a "neutral"low for less distortion than the stress-timed

3. Student responses generally indicated that the language in which the application must fit the

songs served both psychological and educationalnormal length of syllable per musical note re-

needs. In terms of mood, many students indi-gardless of the number of phonemes or gra-

cated that the songs created a relaxed and en-phemes.

joyable atmosphere in the classroom and livened (2) Grammatical Structure, Vocabulary and

up the pace of the lessons; others felt relievedIdiomatic Expressions

from the usual tedium of the classroom and Songs ordinarily provide both literary and

resultantly more receptive. Educationally, the colloquial expressions, which is evidence that

songs were viewed by most students as a means they may be more than just "fun" materials to

of increasing vocabulary, studying Japanese cul- be adopted in addition to the textbook. If the

ture, and discovering the relationship between words of the songs are selected with an effort

language and culture. to further develop the learner's cognition and to

One of the weaknesses of the mechanical pat-

add relevant vocabulary items, the songs become

valuable teaching materials in themselves. For

tern normally associated with the audio-lingual

approach to second language teaching is thatan enthusiastic teacher, it does not require much

such repetition often causes boredom, and con-

time to locate songs which contain grammatical

sequently students gradually lose their motiva-

structures identical to those being taught in

tion. The use of songs, on the other hand, con-

class: everyday expressions, dialogue-style "ques-

tributes greatly to the elimination of such bore-

tion and answer" songs, narration (or ballad)

dom while maintaining the positive rewardsstyle of songs or even those intended to accompany

the drill approach. Songs are also effectivesomein motor skills. Each of these song types can

This content downloaded from

78.30.14.150 on Tue, 23 Jan 2024 10:44:16 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

14 YUKIKO S. JOLLY

be a valuable teaching tool capable of aiding

may contain words or expressions inappropriate

significantly in the accumulation and review

to the main thrust of the particular lesson. As

of morphological and syntactic units and vo-

is the case with any teaching aid or teaching

cabulary items, provided that songs are carefully

methodology, its success or failure is very much

chosen and correctly adapted. dependent upon the teacher using it-such is

(3) Cultural Exposure the case with songs in the foreign language

classroom.

The use of songs also gives students the op-

portunity of acquiring a greater understanding

IV. Conclusion

of the cultural heritage which underlies the

target language. Songs can be selected which My purpose in presenting this paper is to

state a case for the more extensive use of songs

relate to seasonal and historical, as well as moral

in foreign language teaching. Based on the re-

or allegorical aspects of the everyday lives of the

sults of the cited studies in the area, as well as

people. Also to be considered are songs which

are derived from fables, songs requiring psycho-from my own empirical observations in the lan-

guage classroom, I believe that there is an in-

motor skills or with specific purposes, as well as

nate

songs with religious implications. Songs are often receptiveness in us to respond to the rhyth-

mic patterns of language. By using songs as

written to express the deeper feelings of the

teaching

people. The subjects of songs tend to be those aids in the foreign language classroom,

we

things or ideas to which the stronger emotions are merely capitalizing on this natural re-

sponsiveness.

are tied, whether it be joy or sorrow, love or

Now that we are aware of some theoretical

hate. Songs become then a direct aventue to the

basic values of the culture. usefulness and applicability of songs in a foreign

language classroom, it appears that we will be

III. A Word of Caution required to go a step further. Our intuitive

The songs adopted for use in the language feelings will remain only ideas unless they are,

classroom should not contain unfamiliar gram- in some way, proven by means of study and

matical structures, nor grammar or vocabulary experimental research.7 This is a task for those

items not within easy association of the material of us who are interested in developing more

already presented. Also they should not contain pedagogically effective teaching media to further

unusual pitch jumps or subjects not appearing investigate this subject in the future.

in the main textbook which confuse comprehen-

The author is currently conducting a research ex-

sion. It cannot be said, therefore, that there are

periment, "Psycholinguistic Research on Retention

no negative effects possible from the use of songs

Efficiency in Language Acquisition Through Such

in language teaching. Some songs could deviate Rhythmic Means as Verses and Songs." The results

from the desired phonological patterns or the and report of the experiment are expected to be com-

ordinary syntactic arrangement, while others pleted in late Spring, 1975.

NOTICE TO SUBSCRIBERS

in foreign

While subscription-rates of many other December of 1975 will, therefore, be affect

by Modern

language journals take the elevator The the increase. Institutional and foreign st

scription

Language Journal continues to take the stairs.rates will remain at $8.00. In 1976

price

Regretfully the Executive Committee of the of

Na-single copies of the current issue wil

tional Federation of Modern Languageincreased

Teachersto $2.50 (from the present $2.00),

Associations at its 1974 Annual Meetingto $3.00 for a single copy of a back issue fr

decided

that the annual subscription rate for the previous five years (1971-1975). In 1976

individual

subscribers to the Journal must be raised from

price for a complete volume of back issues

be $15.00.

$6.00 to $7.00, effective January 1976. Sub-

scribers who renew their subscriptions expiring

This content downloaded from

78.30.14.150 on Tue, 23 Jan 2024 10:44:16 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Gordon (1999) All About AudiationDocument5 pagesGordon (1999) All About AudiationAT100% (1)

- Developmental Assessment, Warning Signs and Referral PathwaysDocument33 pagesDevelopmental Assessment, Warning Signs and Referral PathwaysJonathan TayNo ratings yet

- Calculus: Gilbert Strang & Edwin HermanDocument2,307 pagesCalculus: Gilbert Strang & Edwin HermanVictorio Maldicas100% (1)

- Nursery Rhymes and Language Learning: Issues and Pedagogical ImplicationsDocument6 pagesNursery Rhymes and Language Learning: Issues and Pedagogical ImplicationsIJ-ELTSNo ratings yet

- Discover Phonetics and Phonology:: A Phonological Awareness WorkbookDocument20 pagesDiscover Phonetics and Phonology:: A Phonological Awareness WorkbookviersiebenNo ratings yet

- Effective Strategies For Teaching Phonemic AwarenessDocument35 pagesEffective Strategies For Teaching Phonemic AwarenessMelissa AcenasNo ratings yet

- Oracle Startup and Shutdown PhasesDocument9 pagesOracle Startup and Shutdown PhasesPILLINAGARAJUNo ratings yet

- CRM-CTT Interleave AdminmanualDocument141 pagesCRM-CTT Interleave AdminmanualpajdasNo ratings yet

- Young Learners' Educational ModeDocument20 pagesYoung Learners' Educational ModeOkan EmanetNo ratings yet

- Nursery Rhymes 1 PDFDocument6 pagesNursery Rhymes 1 PDFMaria Theresa AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- ENGLISH 9 DLL NewDocument37 pagesENGLISH 9 DLL NewLORAINE LACERNA GAMMAD0% (1)

- The Range of The Bodhisattva - A Mahāyāna SūtraDocument12 pagesThe Range of The Bodhisattva - A Mahāyāna Sūtramaximo cosetti100% (2)

- Grade 7 Week 8 Q1Document3 pagesGrade 7 Week 8 Q1Aristotle TomasNo ratings yet

- Ra 10157Document4 pagesRa 10157Kelly Espiritu100% (2)

- Foreign Language Pronunciation Skills and MusicalDocument6 pagesForeign Language Pronunciation Skills and MusicalPetra Kitti JuhászNo ratings yet

- Intuitive-imitative Approach Versus Analytic-linguistic Approach toward Teaching - T -, - Δ -, and - w - to Iranian StudentsDocument7 pagesIntuitive-imitative Approach Versus Analytic-linguistic Approach toward Teaching - T -, - Δ -, and - w - to Iranian StudentsLinhLyNo ratings yet

- LCS QE ReviewerDocument35 pagesLCS QE ReviewerRocelle RellamaNo ratings yet

- PRACTICE TEST. Linguistica Mayo 2023Document4 pagesPRACTICE TEST. Linguistica Mayo 2023Gia Nella BossoNo ratings yet

- Linguistics7 PDFDocument7 pagesLinguistics7 PDFMus TaphaNo ratings yet

- Phonological AwarenessDocument11 pagesPhonological AwarenessJoy Lumamba TabiosNo ratings yet

- Retrieved From: British Council Core Inventory Posters Ments/core - Inventory - Posters PDFDocument7 pagesRetrieved From: British Council Core Inventory Posters Ments/core - Inventory - Posters PDFAnna PinedaNo ratings yet

- Improving Pronunciation Ability by Using Animated Films: Titik Lina Widyaningsih STKIP PGRI TulungagungDocument16 pagesImproving Pronunciation Ability by Using Animated Films: Titik Lina Widyaningsih STKIP PGRI TulungagungPhuong AnhNo ratings yet

- Montrul de La Fuente Davidson Foote 2013Document32 pagesMontrul de La Fuente Davidson Foote 2013Fátima Pacheco BorjaNo ratings yet

- Hisagi2014 BilingualismDocument20 pagesHisagi2014 Bilingualismapi-337162869No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan and Critical ReflectionDocument4 pagesLesson Plan and Critical Reflectionapi-522586054No ratings yet

- E.I.L. French - An Audio-Lingual Course. Volume I.Document246 pagesE.I.L. French - An Audio-Lingual Course. Volume I.Sciarium Numero1No ratings yet

- Syllabus Teaching Listening SpeakingDocument5 pagesSyllabus Teaching Listening SpeakingjessNo ratings yet

- Speech To Song IllusionDocument9 pagesSpeech To Song IllusionXie WenhanNo ratings yet

- JB 95 083Document14 pagesJB 95 083eulaNo ratings yet

- Native Language Interference in Learning English Pronunciation: A Case Study at A Private University in West Java, IndonesiaDocument16 pagesNative Language Interference in Learning English Pronunciation: A Case Study at A Private University in West Java, IndonesiaDiahNo ratings yet

- 2006 - J - Music To Language Transfer Effect - May Melodic Ability Improve Learning of Tonal Languages by Native Nontonal SpeakersDocument5 pages2006 - J - Music To Language Transfer Effect - May Melodic Ability Improve Learning of Tonal Languages by Native Nontonal Speakerscher themusicNo ratings yet

- October 2-6, 2023 DLLDocument6 pagesOctober 2-6, 2023 DLLjha RoxasNo ratings yet

- Acoustic Similarity of Inner and Outer Circle Varieties of Child-Produced English VowelsDocument17 pagesAcoustic Similarity of Inner and Outer Circle Varieties of Child-Produced English Vowelshye-sook parkNo ratings yet

- Linguistic and Cultural Education For BildungDocument6 pagesLinguistic and Cultural Education For Bildunggülay doğruNo ratings yet

- Journal of Memory and Language: Saúl Villameriel, Patricia Dias, Brendan Costello, Manuel CarreirasDocument12 pagesJournal of Memory and Language: Saúl Villameriel, Patricia Dias, Brendan Costello, Manuel CarreirasMaisun Haj-Ali SafloNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Students' Errors in Pronouncing English Diphthongs at The First Semester of Stain Jurai Siwo MetroDocument6 pagesAn Analysis of Students' Errors in Pronouncing English Diphthongs at The First Semester of Stain Jurai Siwo MetroMARCELANo ratings yet

- Relota, Mariel Ann Laureta From English 2-B Final Term RequirementDocument4 pagesRelota, Mariel Ann Laureta From English 2-B Final Term Requirementrooragnarokorigin110No ratings yet

- Lecture 9Document16 pagesLecture 9KateNo ratings yet

- Lehmann HumanisticBasisSecond 1987Document9 pagesLehmann HumanisticBasisSecond 1987Rotsy MitiaNo ratings yet

- DLL Week 1 - English 7Document5 pagesDLL Week 1 - English 7Lheng DacayoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Pronunciation HandoutDocument49 pagesIntroduction To Pronunciation HandoutRheeva AnggaNo ratings yet

- Primer Parcial PhonologyDocument87 pagesPrimer Parcial PhonologyLINDA SAMAYA DIAZ DE LA CRUZNo ratings yet

- Leon Guinto Memorial College, Inc.: Course Title Course Number School Year & Term FacultyDocument21 pagesLeon Guinto Memorial College, Inc.: Course Title Course Number School Year & Term FacultyZarahJoyceSegoviaNo ratings yet

- Analysis On Dialect DifferencesDocument4 pagesAnalysis On Dialect DifferencesAlditsa Fuad Sii AgedasNo ratings yet

- Language Arts Subject For Elementary - 1st Grade - The Sounds - L - and - N - by SlidesgoDocument10 pagesLanguage Arts Subject For Elementary - 1st Grade - The Sounds - L - and - N - by SlidesgoKhopifah nurmutiaNo ratings yet

- Phonemic Awareness On Consonant Sounds FinalDocument30 pagesPhonemic Awareness On Consonant Sounds FinalMikkaella RimandoNo ratings yet

- Course Guide EL 100Document4 pagesCourse Guide EL 100Joevannie AceraNo ratings yet

- ED243144Document21 pagesED243144Zikri AhmadNo ratings yet

- DLL - English 6 - Q1 - W1Document4 pagesDLL - English 6 - Q1 - W1Lopez Rhen DaleNo ratings yet

- Task 4 - Angelica Andreina Botello RondonDocument5 pagesTask 4 - Angelica Andreina Botello RondonbotelloNo ratings yet

- Method of PronunciationDocument31 pagesMethod of PronunciationFaizal HalimNo ratings yet

- LCS Midterm (Reviewer)Document11 pagesLCS Midterm (Reviewer)marielmaxenne.dorosan.cvtNo ratings yet

- ENG 7 The Empirical Basis, My ReportDocument18 pagesENG 7 The Empirical Basis, My ReportDhon Callo100% (1)

- Using English Songs To Improve Young Learners' Listening ComprehensionDocument11 pagesUsing English Songs To Improve Young Learners' Listening ComprehensionIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Task Week 5 Melt - Muhammad Azka Rivaldi - 192122049 - C ClassDocument4 pagesTask Week 5 Melt - Muhammad Azka Rivaldi - 192122049 - C ClassAzka RivaldiNo ratings yet

- Second Edition, Published by Elsevier, and The Attached Copy Is Provided by ElsevierDocument5 pagesSecond Edition, Published by Elsevier, and The Attached Copy Is Provided by ElsevierAnand KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Utopian Goals For Pronunciation Teaching: Tracey M. DerwingDocument14 pagesUtopian Goals For Pronunciation Teaching: Tracey M. DerwingBrady GrayNo ratings yet

- OK E7b4Document8 pagesOK E7b4yd pNo ratings yet

- First Day Second Day Third Day Fourth Day: Iii. Learning ResourcesDocument5 pagesFirst Day Second Day Third Day Fourth Day: Iii. Learning ResourcesChristian Jay UmaliNo ratings yet

- Dillon, de Jong y Pisoni (2011) Phonological Awareness, Reading Skills, and Vocabulary Knowledge in Children Who Use Cochlear ImplantsDocument22 pagesDillon, de Jong y Pisoni (2011) Phonological Awareness, Reading Skills, and Vocabulary Knowledge in Children Who Use Cochlear Implantsilhan.alarikNo ratings yet

- Linguistics Groups 1 2 3 4 5 6Document13 pagesLinguistics Groups 1 2 3 4 5 6itsjustaperson04No ratings yet

- Oral Com Q1 W4Document3 pagesOral Com Q1 W4Jade SolerNo ratings yet

- (Danny D. Steinberg, Hiroshi Nagata, David P. Alin (Z-Lib - Org) (1) - DikompresiDocument465 pages(Danny D. Steinberg, Hiroshi Nagata, David P. Alin (Z-Lib - Org) (1) - Dikompresimelyagustinaaa16No ratings yet

- Psycholinguistic. Language, Mind and Word 2nd Edition Danny Steinberg PDFDocument104 pagesPsycholinguistic. Language, Mind and Word 2nd Edition Danny Steinberg PDFNika AgustinaNo ratings yet

- Language Teaching in the Linguistic Landscape: Mobilizing Pedagogy in Public SpaceFrom EverandLanguage Teaching in the Linguistic Landscape: Mobilizing Pedagogy in Public SpaceDavid MalinowskiNo ratings yet

- Activity 1 - Melvin EstreraDocument2 pagesActivity 1 - Melvin EstreraMelvinchong EstreraNo ratings yet

- Cockney+vs+Estuary+English Converted by AbcdpdfDocument2 pagesCockney+vs+Estuary+English Converted by Abcdpdfflorencia gomezNo ratings yet

- Grade 12: Tvl-Ict Install Operating System and Drivers For Peripheral / DevicesDocument10 pagesGrade 12: Tvl-Ict Install Operating System and Drivers For Peripheral / DevicesALBERT ALGONESNo ratings yet

- Machinelearning JoivianDocument8 pagesMachinelearning Joivianayyoraama chandraNo ratings yet

- Oracle® Process Manufacturing: Cost Management API User's Guide Release 11iDocument108 pagesOracle® Process Manufacturing: Cost Management API User's Guide Release 11iSayedabdul batenNo ratings yet

- MaxParallel For SQL Server Best Practices GuideDocument3 pagesMaxParallel For SQL Server Best Practices GuideTechypyNo ratings yet

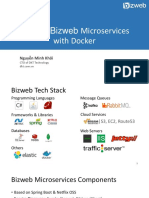

- Building Bizweb Microservices with Docker: Nguyễn Minh KhôiDocument25 pagesBuilding Bizweb Microservices with Docker: Nguyễn Minh KhôinguoinhenvnNo ratings yet

- ICS253 161 1 Foundations Logic Proofs S 1 1 1 4 PIDocument75 pagesICS253 161 1 Foundations Logic Proofs S 1 1 1 4 PIDawod SalmanNo ratings yet

- Philippine External Relations With Southeast AsiaDocument26 pagesPhilippine External Relations With Southeast AsiaKaren Gail JavierNo ratings yet

- Sanskrit Thesis PDFDocument4 pagesSanskrit Thesis PDFyessicadiaznorthlasvegas100% (2)

- Features and Modes of 8086Document11 pagesFeatures and Modes of 8086ABHishekNo ratings yet

- CBA 5ème Collège Privé MontesquieuDocument13 pagesCBA 5ème Collège Privé MontesquieuLysongo OruNo ratings yet

- Braj ArchiveDocument7 pagesBraj ArchiveJigmat WangmoNo ratings yet

- The Modern Business LetterDocument43 pagesThe Modern Business LetterJessa Mei Diana Mendoza100% (5)

- Movie Scene FullDocument7 pagesMovie Scene FullChin Yee LooNo ratings yet

- WorksheetDocument4 pagesWorksheeteduardo scateglianiNo ratings yet

- Balbon - Baby Shaine TLE-ICT-CSSDocument33 pagesBalbon - Baby Shaine TLE-ICT-CSSamethyst BoholNo ratings yet

- RIZAL PRELIM CHAPTER 1 5 Edited Edited EditedDocument73 pagesRIZAL PRELIM CHAPTER 1 5 Edited Edited EditedAJ DNo ratings yet

- Games For Kids: How To Play Bam!: You Will NeedDocument13 pagesGames For Kids: How To Play Bam!: You Will Needapi-471277060No ratings yet

- Scolnicov PDFDocument9 pagesScolnicov PDFEduardo CharpenelNo ratings yet

- GDI PlusDocument210 pagesGDI PlusBelhassen LourimiNo ratings yet

- UiPath Certified RPA Associate v1.0 - EXAM DescriptionDocument7 pagesUiPath Certified RPA Associate v1.0 - EXAM DescriptionabhaysisodiyaNo ratings yet

- Oral DirectionsforstudentsDocument3 pagesOral DirectionsforstudentsJames HanNo ratings yet

- FS Industrie (PDF - Io)Document42 pagesFS Industrie (PDF - Io)don dadaNo ratings yet