Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chakrabarti TowardDualismNyyaVaieika 1991

Chakrabarti TowardDualismNyyaVaieika 1991

Uploaded by

AnamikaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chakrabarti TowardDualismNyyaVaieika 1991

Chakrabarti TowardDualismNyyaVaieika 1991

Uploaded by

AnamikaCopyright:

Available Formats

Toward Dualism: The Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika Way

Author(s): Kisor Kumar Chakrabarti and Chandana Chakrabarti

Source: Philosophy East and West , Oct., 1991, Vol. 41, No. 4, The Sixth East-West

Philosophers' Conference (Oct., 1991), pp. 477-491

Published by: University of Hawai'i Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1399645

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

University of Hawai'i Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Philosophy East and West

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

TOWARD DUALISM: THE NYAYA-VAISESIKA WAY Kisor Kumar

Chakrabarti

Professor

This essay is expository and consists of three parts. TheCenter

firstfor Philosophy

part briefly

of Science

states the basic Nyaya-Vaisesika thesis about the self. The second part

University of

studies in detail some well-known Nyaya-Vaisesika arguments in support

Pittsburgh

of their theory of self and highlights some points of interpretation not

Chandana

heretofore clearly explained. The third part is devoted toChakrabarti

the Nyaya-

Vaisesika critique of the Buddhist theory of self. Professor

Department of

Philosophy

University of

According to Gotama,' the founder of the Nyaya school, Delaware (iccha),

desire

aversion (dvesa), volition (prayatna), pleasure (sukha), pain (duhkha), and

cognition (jnana) are the liiga of the self (atman). Each one of these is an

identifying mark (laksana) of the self and thus each one is a probans (hetu)

for inferring the existence of the self. When it is said that desire and so

forth are identifying marks of the self, what is meant is that each one of

these marks is a characteristic feature of all selves and of nothing else.

An identifying mark (laksana), like the definiens in Western philosophy, is

required to be coextensive (samaniyata) with the subject and should be

neither too wide nor too narrow. With the help of any one of such

identifying marks, the self may be distinguished from everything else that

is not a self; in this way the referent (sakya) of the word "self" or "I"

becomes fixed.

Desire and so forth are specific qualities (visesa guna) of the self; they

do not belong to any other kind of substance (dravya). The self also has

some other common qualities (samanya guna), such as number (sarmkhya),

separateness (prthaktva), and so forth, which it shares with all other

substances. These common qualities are not acceptable as identifying

marks of the self, because they are not limited to selves. Although each

one of the six specific qualities is acceptable as an identifying mark of the

self, the complex property produced by the conjunction of all these six

qualities, which, too, is coextensive with the self, is not acceptable as an

identifying mark of the self. This is because an identifying mark must be

not only coextensive with its bearer but also simple (laghu). The require-

ment of simplicity holds that, other things being equal, something with

fewer constituents is to be preferred to something with more constituents

(sarnra-krta-laghava). Thus the complex property resulting from thePhilosophy

con- East & West

junction of the six specific qualities, which has more components than 41, Number 4

Volume

any one by itself, does not qualify as an identifying mark. It mayOctober

also 1991

477-491

be noted that, in addition to the six already mentioned, the self also

possesses three other unobservable (atTndriya) specific qualities, namely,

? 1991

merit (dharma), demerit (adharma), and impression (bhavana). Eachbyof University of

these is also coextensive with the self.2 But none of them counts as an Hawaii Press

477

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

identifying mark of the self: for (in yet another ramification of the require-

ment of simplicity), other things being equal, what is observed is to be

preferred to what is unobserved.

II

In what sense, then, are desires said to be the probantia (hetu) for the

inference of the self. One well-known proof briefly stated by Vatsyayana3

is as follows: "Desire, etc., are qualities; but qualities are supported by

substance; that which is the support of these is the self."4 Uddyotakara5

has observed that before one can conclude that the self is the support of

desire and so forth, one must eliminate the other eight substances recog-

nized by the Nyaya-Vaisesika school, namely, earth (prthivf), water (jala),

fire (tejas), air (vayu), akasa (the imperceptible substratum of sound),

space (dik), time (kala), and inner sense (manas). He suggested that the

fact that desire and so forth are directly known by the self (atmasahmvedya)

and the fact that these are not perceptible by the external sense organs

provides the ground for the elimination of other substances. Thus, the

qualities of the first five substances, namely, earth, water, fire, air, and

akaJa, are perceived not only by a particular person but also by other

persons; further, these qualities of earth and so forth are perceived by the

external sense organs. Since one's own desire and so forth can be directly

known only by oneself and not by anyone else and since these are not

objects of external perception, these cannot be the qualities of earth

and so forth. Further, desire and so forth cannot be attributed to the

remaining three substances, namely, space, time, and the inner sense, for

the qualities of these substances, like these substances themselves, are

imperceptible. Since none of the other recognized substances can be

accepted as the substratum of desire and so forth, an additional sub-

stance must be inferred as their substratum.

The argument above has two distinct parts. The first part (by confining

our attention only to desire) may be reformulated in the Barbara form as

follows:

All qualities belong to a substance.

All desires are qualities.

Therefore, all desires belong to a substance.

The second part of the proof may be reformulated as a disjunctive

syllogism as follows:

Desire belongs to earth or desire belongs to water or desire belongs to fire or

desire belongs to air or desire belongs to akaJa or desire belongs to space or

desire belongs to time or desire belongs to inner sense or desire belongs to

Philosophy East & West an additional ninth substance called the self.

478

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Desire does not belong to earth and desire does not belong to water and

desire does not belong to fire and desire does not belong to air and desire

does not belong to akasa and desire does not belong to space and desire

does not belong to time and desire does not belong to inner sense.

Therefore, desire belongs to an additional ninth substance called the self.

The whole argument may be put in the symbolic notation as follows

(by presupposing that the predicates are non-empty):

Dx = x is a desire Qx = x is a quality Sx = x belongs to a substance

Ex = x belongs to earth Wx = x belongs to water Fx = x belongs to

fire Ax = x belongs to air Kx = x belongs to akasa Ix = x belongs

to space Tx = x belongs to time Mx = x belongs to inner sense

Nx = x belongs to an additional ninth substance called the self

(x)(Dx D Qx)

(x)(Qx = Sx)

Therefore, (x)(Dx = Sx)

(x)(Dx = Ex) v (x)(Dx = Wx) v (x)(Dx D Fx) v (x)(Dx = Ax) v (x)

(Dx D Kx) v (x)(Dx = IX) v (x)(Dx = Tx) v (x)(Dx = Mx) v (x)(Dx = Nx)

(x)(Dx -Ex) (x)(Dx D -Wx)' (x)(Dx - Fx) * (x)(Dx D -Ax).

(x)(Dx -Kx) (x)(Dx -Ix) (x)(Dx -Tx) (x)(Dx -Mx).

Therefore, (x)(Dx D Nx)

Vacaspati Misra (ninth century A.D.)6 offered another interpretation of

the argument from desire for inferring the existence of the self as a

spiritual, noncorporeal substance. He suggests that desire and so forth

could be taken as the subject of inference (paksa: similar to the minor

term), 'being a quality of a person belonging to the self' as the probandum

(sadhya: similar to the major term), and 'being qualities which do not

belong to the other eight substances' as the probans (hetu: similar to the

middle term). Now the inference may be recast as follows (to be called

the argument 'A'):

Whatever is a quality of a person that does not belong to the self is not a

quality which does not belong to the other eight substances, for example,

color and so forth.

Desire is a quality which does not belong to the other eight substances.

Therefore, desire belongs to the self.

Vacaspati Misra points out that in the proof above, the first general

premise should not be replaced by its contrapositive, namely, that what- Kisor Kumar

ever is a quality which does not belong to the other eight substances is Chakrabarti

a quality of a person that belongs to the self. If the truth of this gen- Chandana Chakrabarti

479

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

eral proposition is questioned, no particular positive examples (anvayi-

drstanta) can be adduced in its support. However, there is no dearth of

particular negative examples (vyatireki-drstanta) like color, smell, and so

forth, which are qualities of a person that do not belong to the self and

are also qualities which belong to some of the other eight substances.

Such examples can provide adequate evidence for the general premise

used in the proof if the truth of that premise is questioned.

The point can be clarified further by looking at another similar argu-

ment that the living body is not without a self because it breathes. In

accordance with the suggestions of Uddyotakara and Vacaspati Misra,

the inference may be formulated as follows:

Whatever is without the self does not breathe.

The living body breathes.

Therefore, the living body is not without the self.

Here, too, the first premise should not be replaced by its contrapositive,

namely, that whatever breathes is not without the self. Once again, no

particular positive examples can be provided in support of this general

proposition if its truth is challenged; from the very nature of the case

living bodies are the only things which both breathe and are not without

the self (in the Nyaya view animals, too, have selves; see later in this

essay). But there are innumerable particular negative examples like a

stone, a box, and so forth, which are without the self and also do not

breathe. With the help of them the truth of the general premise actually

used can be supported if needed.

It should be clear that Uddyotakara and Vacaspati Misra have taken

care to give some bite to these proofs against their materialist oppo-

nents. The materialist will reject the general proposition that whatever

breathes is not without the self. The dualist cannot use examples of living

bodies to support this general proposition, for living bodies are the sub-

ject of inference. The methodological principle (usually accepted by

Indian philosophers) is that the particular examples, whether positive or

negative, to be brought in support of the general premise must exclude

the subject. Since the bone of contention is whether living bodies are

without the self or not, it would be circular to use living bodies them-

selves as evidence for the premise. The dualist also cannot hope to find

any undisputed examples different from living bodies because, according

to his own position, living bodies are the only things which are not

without a self. To resolve this difficulty, Uddyotakara and others have

used 'whatever is without the self does not breathe' as the general

premise. Any inanimate object can be cited as evidence in support of

this premise; for the materialist, too, holds that things like stones are

Philosophy East & West without the self and do not breathe. Thus there are particular examples

480

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

which can lend support to the general premise, and these examples

are acceptable to both the dualist and the materialist. But there are no

undisputed counterexamples. The only things which breathe are living

bodies. In the opinion of the materialist living bodies are devoid of any

self in the sense of a spiritual, noncorporeal substance. But the materialist

cannot cite living bodies as the counterexamples, for this is precisely

where the bone of contention lies. The living bodies are the subject of

inference. It is generally agreed (in the Indian logical tradition) that the

counterexamples to be brought in refutation of a premise must exclude

the subject of inference. Since there are corroborative examples accepted

by both the dualist and the materialist and there are no undisputed

counterexamples, the general proposition 'whatever is without the self

does not breathe' may be accepted as a reliable premise. The other

premise, namely, 'the living body breathes', is accepted as true by both

the dualist and the materialist. The argument is formally valid. Since both

the premises are reliable and the argument is formally valid, the conclu-

sion, namely, 'the living body is not without the self', may be claimed to

have been reasonably vindicated. The ball is now in the court of the

materialist, who should either find some convincing way of countering

the force of the argument or yield to the dualist. From the point of

view of merely formal validity it makes no difference whether 'whatever

breathes is not without the self' or 'whatever is without the self does not

breathe' is used as a premise; the argument would be formally valid in

either case. But for the reasons explained above only the use of the latter

is prescribed as a premise, and thereby the dualist is able to secure an

advantage over the materialist, which advantage would have been lost if

the former were used as a premise instead.

Let us now take another look at the argument 'A'. It has already been

explained why in this argument the first premise should not be replaced

by its contrapositive. But the really sensitive part in this argument lies in

the second premise, which makes two substantial claims, namely, (1) that

desire and so forth are qualities and (2) that these cannot belong to the

other eight substances. That desire and so forth are qualities is shown by

such experiences as 'I am happy', 'I know', ' wish', and so forth, in which

desire and so forth appear to be attributes of the I or the self. (Further

light will be thrown on this in connection with the discussion of the

Buddhist no-ownership theory of self.) The second claim clearly includes

the thesis that desire, cognition, and so forth cannot be regarded as

qualities of the body. Since this thesis is bound to be challenged by the

materialist, the Nyaya-Vaisesika philosophers have argued at length to

defend it. The main reasons for rejecting the view that desire and so forth

are qualities of the body are in what follows. Kisor Kumar

(1) If desire and so forth were qualities of the body, like other qualities Chakrabarti

of the body, these, too, should have been public objects and open to theChandana Chakrabarti

481

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

observation by one's own self as well as other selves (atmaparatmaprat-

yaksa). But on the contrary these are private and open to observa-

tion only by one's own self (atmasamrvedya). This goes to show the

difference of cognition and so forth from the qualities of the body

(sarTragunavaidharmya). The latter are either imperceptible (atTndriya) or

perceptible by an external sense organ (bahyakaranapratyaksa) such as

the eye, the ear, and so forth. But cognition and so forth are neither

imperceptible nor perceptible by an external sense organ, but intro-

spectible only by the inner sense (manovisayatvat) (Nyayadarsanam, pp.

893-895). Thus the materialist thesis has to be rejected to account for

the privacy of our inner experiences.

(2) Consciousness (chetana) cannot be a quality of the body (na

sarTraguna) because it permeates the whole body (sarnravyapitvat). The

point is that consciousness is found in every part of the body (with the

exception of the hair, nails, and so forth, which, according to these

philosophers, are not parts (avayava) of the body in the strict sense). If

consciousness were a quality of the body, since the parts of the body are

numerous, there should have been numerous cognizers and selves in the

same body (praptam chetanabahutvam). The materialist could reply that

the body as a substantial whole (avayavin) is different from its parts and

is numerically one. Consciousness could be regarded as a quality of only

the body as a substantial whole and not of the numerous parts; thus the

difficulty of there being many selves in the same body could be avoided.

But this reply would be futile, for there is no satisfactory way to explain

why, from the materialist point of view, consciousness should be a quali-

ty of only the body as a substantial whole and not of the parts as

well. It would not help on the part or the materialist to suppose that

consciousness is a quality of only one particular part of the body. For

then it cannot be explained satisfactorily why consciousness is found in

every part of the body. The materialist cannot escape by boldly suppos-

ing that there are many selves in the same body. Then the experiences

of one part would be accessible only to that part (pratyayavyavasthapra-

sanga) just as the experiences of one person are accessible only to that

person (Nyayadarsanam, p. 892).

(3) Consciousness is not a quality of the body because it is non-

cotemporal with the body (ayavaddravyabhavin). The body may con-

tinue to exist for a while after death without any noticeable material loss

although no consciousness can be possibly found in it at that time. Thus

it is clear that consciousness does not belong to the body as long as the

body exists. This strongly suggests that the presence of consciousness in

the body is not due to the body itself but its association with another

substance. It is true that the quality of a substance need not be co-

temporaneous with it. But in every case where the quality of a substance

Philosophy East & West changes, one can find an opposite (pratidvandin) quality in it. In the dead

482

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

body can be found no such opposite quality which can explain the loss

of consciousness. It is also true that certain processes which are essential

for conservation of life, such as exhalation and inhalation, constant circu-

lation of blood, and so forth, are always missing in a dead body. But to

explain the loss of consciousness in a dead body as being due to the

stoppage of such vital processes would be grossly circular: from the

Nyaya-Vaisesika point of view the very presence of such vital processes

in a living body serves as a pointer to the existence of an immaterial

substance which possesses consciousness as a quality. In other words,

the constant and perfectly regular upward and downward motions tak-

ing place in a living body require, from the Nyaya-Vaisesika standpoint,

for its explanation the volition (prayatna) of a conscious superintendent

(adhis.thata).7 Similarly, such typical phenomena as a living organism

growing to its maturity (vrddhi) or recovering from bodily injury (ksata-

bhagnasarhrohana) cannot be accounted for without the volition of a

conscious agent.8 Arguing from the analogy of a house owner making

additions or repairs to his household, the Nyaya-Vaisesika philosophers

maintain that the conscious self inhabiting a living body supervises the

process of organic growth and repair of wounds. They are not deterred

by the fact that if the presence of life is to serve as a sign for inferring the

self, not only the bodies of humans but also the bodies of all animals as

well as plants would have to be regarded as being inhabited by conscious

selves. They hold without any ambiguity that there are selves for humans

as well as for other animals and also plants and maintain unhesitatingly

that even the plants and vegetables have consciousness hidden inside

them (antahsarhjina) and are capable of experiencing pain and pleasure

(sukhaduhkhasaman vitah),

(4) Consciousness cannot be a quality of the body because the body

is a material product. This argument is based on the premise that what-

ever is a material product is not conscious (yat bhutakaryam na tat

chetanam).9 The premise is well supported by innumerable positive ex-

amples such as pots, stones, and so forth, which are admittedly material

products as well as unconscious. There are also no undisputed counter-

examples. Although the materialist claims that the living body is con-

scious, the dualist rejects that claim. Since a legitimate counterexample

must be acceptable to both the parties in a dispute, it would be futile

on the part of the materialist to cite living bodies as counterexamples.

The argument may be restated as follows:

Whatever is a material product is unconscious.

All living bodies are material products.

Therefore, all living bodies are unconscious. Kisor Kumar

Chakrabarti

The same argument may be stated in the symbolic notation as follows Chandana

483

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

(M = material product, U = unconscious, L = living body):

(x)(Mx = Ux)

(x)(Lx = Mx)

Therefore, (x)(Lx = Ux)

(5) Another similar argument is that consciousness cannot be a quality

of the body because it is colored. The argument is based on the premise

that whatever is colored is not conscious (yat rupavat na tat chetanam).

Once again, the premise is supported by numerous positive examples

like pots, houses, and so forth, which are colored and unconscious. There

are no undisputed counterexamples as well. It would not be permissible

to produce living bodies as counterexamples, for the dualist rejects the

claim that living bodies are conscious. The argument may be reformulated

as follows:

Whatever is colored is devoid of consciousness.

All living bodies are colored.

Therefore, living bodies are devoid of consciousness.

Other similar arguments to show that consciousness is not an attribute

of the body may be derived from the fact that the body is changeable

(parinaimitvat) and from the fact that the body has a definite structure

(sannivesavisistatvat).10 These two arguments rely, respectively, on the

premises that (1) all that is changeable is devoid of consciousness and

that (2) all things having a definite structure are without consciousness.

For these premises, too, there are numerous positive examples in their

favor, but there are no undisputed counterexamples.

(6) If consciousness were a quality of the body, it becomes difficult to

explain how a person is able to remember in his old age his childhood

experiences (sarnrasya chaitanye balye vilokitasya sthavire smarananupa-

patteh). If consciousness belonged to the body and the self and the body

were the same, the old body would have to be the agent of remembering

and the infant body would have to be the agent of having the original

experience. But the old body and the infant body are different, and it is

clear that what is experienced by one cannot be remembered by an-

other. Thus the old body, being different from the infant body, cannot

remember what was experienced by the latter."

The materialist could claim by adopting the Aristotelian view that in

spite of the phenomenal difference in shape, size, and so forth, the old

body, insofar as it is a substance, is the same as the infant body. From the

Aristotelian standpoint, what makes a substance the same as an earlier

substance is that its matter is the same, or derived from the matter of the

Philosophy East & West former substance by gradual replacement, without losing the essential

484

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

properties which represent its form. For living things, moreover, even

total replacement of matter-provided it is gradual, and provided the

structural change, too, is gradual-will not destroy identity. Since thus

the old body may be said to be the same as the infant body in spite of

the total replacement of matter, the difficulty of accounting for child-

hood memory may be resolved.

But this solution, it must be pointed out, is not acceptable from the

Nyaya-Vaisesika point of view. According to the latter, even the re-

placement of a single part (avayava) would destroy a substantial whole

(avayavin) and bring about another substance which, though utterly

similar, is absolutely different from the former substance. This position

has been adopted by the Nyaya-Vaisesika philosophy, not as an ad hoc

assumption suitable for the present case, but as a solution to the wider

issue of substantial change and sameness. It would not be profitable to

enter into a discussion of the merits/demerits of the Nyaya-Vaisesika and

the Aristotelian views of the sameness of a substance here. Suffice it to

note that, given the Nyaya-Vaisesika view, the problem of accounting for

childhood memory remains a difficult issue for the materialist.

Even if it is conceded that the old body is different from the infant

body, the materialist could say by way of a rejoinder that the former is

related to the latter by an unbroken causal chain and that the impression

(sarhskara) of the childhood experience passed on through the chain

could be revived on the appropriate occasion.'2 In response it may be

noted that the materialist in that case should find an explanation of why

the experiences of the mother are not passed on to the child. It will not

do on the part of the materialist to suppose that the experiences of the

mother belong to a particular part of the mother's body which the child

does not have and hence that the experiences of the mother are not

passed on to the child. The point is that the mother's body is causally

related to the child's body. If the experiences belonging to one body can

be passed on to other bodies by virtue of a causal relationship, the

same should happen with the mother and child as well. There is no

difference between the two cases. Further, the materialist would have to

suppose also that each time a new body is added to the causal chain, the

impression residing in the previous body is destroyed and a new impres-

sion produced. Thus the materialist would have to be committed to the

origin and destruction of an indefinitely large number of impressions.

From the Nyaya-Vaisesika point of view, however, the self is different

from the body and remains the same in spite of the bodily changes.

There is, then, no need to suppose that the impression is replaced by a

new impression each time a new body is added to the causal chain.

In this respect the dualist view appears to be more economical, forKisor

it can

Kumar

account for childhood memory by postulating far fewer impressions than

Chakrabarti

required in the materialist view. Chandana Chakrabarti

485

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Ill

Just as the Nyaya-Vaisesika philosophers have sought to refute the

materialist view, so also they have argued at length against the Buddhist

view (similar to the Humean view) that the self is nothing more than a

bundle of particular perceptions, feelings, and so forth. Hume wrote:

"When I enter most intimately into what I call myself, I always stumble

on some particular perception or other.... I never catch myself without

a perception" (Treatise, Bk. 1, pt. 4, no. 6). Significantly, some Nyaya-

Vaisesika philosophers agree with Hume that we can never catch our-

selves without a perception, and so forth. Visvanatha writes clearly:

"... the self is perceived as related to cognition, pleasure, etc., and not

otherwise-through such awarenesses as 'I know', 'I do', etc."'3 Thus

Visvanatha rules out that the self can be perceived without some partic-

ular perception, and so forth. Still the disagreement with Hume remains

fundamental. Hume claims that he fails to find the self or the common

subject. But according to these Nyaya-Vaisesika philosophers (as also the

MTmamsa philosophers), the self is perceived through I-consciousness

(aharm-pratyaya-gamyatvat atma pratyaksa) (Nyayamanjarn, pt. 2, p. 4).

Thus "the awareness that I am happy directly reveals the self also" (aharh

sukhTti tu jinaptiratmanah api prakasika) (ibid., p. 7). Moreover, the aware-

ness that I know cannot be maligned even by a small grain of fault: of this

the self is the chief content (na khalu aham janami iti pratyayah kenacit

alp?yasa dosarenuna dhusarfkartumr paryate tadasya atma eva mukhyo

visayah) (ibid., p. 4). In other words, in such particular experiences as 'I am

happy', 'I know', 'I wish', and so forth the self is revealed as the common

subject. This direct testimony goes against the Buddhist (and the Humean)

view.

Other Nyaya-Vaisesika philosophers have denied that the self is per-

ceived and have offered reasonings (fully endorsed also by those holding

that the self is perceived) to prove the selfs permanence. Desire and so

forth play the crucial role in these reasonings, too. "When a person has

earlier experienced pleasure from some kind of thing, upon coming

across later another thing of the same kind and remembering its pleas-

antness he wishes to acquire it. A wish originating in this way leads to the

inference of a subject (asraya) capable of synthesizing past and present

experiences (purvaparanusandhanasamartha)" (ibid., p. 8). The claim, then,

is that desire can be accounted for only by accepting that the owner of

the past and the present experiences is the same (samanakartrka).

In the same way aversion (dvesa) also serves as a sign for personal

identity and continuity. "When a person has experienced pain from

some kind of thing, upon coming across again that sort of thing and

remembering its painfulness he has aversion for it. This cannot be ex-

plained without the same synthesizer (pratisandhata)" (ibid., p. 9). Simi-

Philosophy East & West larly, pleasure, pain, volition, and cognition would prove personal identity

486

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

so long as these are based on memory, for "a thing experienced by

one cannot be remembered by another (na anyad.rstah arthah smartum

anyena sakyate)." In particular, each of the four sources of knowledge

(recognized by the Nyaya), namely, perception, inference, upamana, and

verbal knowledge, lends support to the identity and continuity of the self.

Thus "recognitive perception (pratyabhijna) could not take place if the

knower were different. Just as it proves the sameness of the known

object, so also it proves the sameness of the knowing person" (ibid.,

p. 15). In other words, when a person recognizes something he is seeing

now, say a statue, to be the same as that which he has seen before,

the truth of such recognitive perception can be accounted for only if the

statue seen now is the same as that seen before and the person recog-

nizing it is the same as he who saw it before. Again, "Knowledge of

universal connection (avinabhavagrahanam), knowledge of the probans

(lingajnanam), remembrance of the relation (anvayasmaranam) between

that and the probandum, knowledge of the probandum (lirigipramiti)-

since inference involves these, it could not take place if the knower were

different" (ibid., p. 15). To explain: when one infers that the probandum

(lirigin) belongs to the subject (paksa) on the basis of the knowledge that

the probans (liriga) belongs to the subject and the knowledge that the

probans is universally concomitant with the probandum after having

ascertained earlier through observation that the probans and the prob-

andum are so related, the accounting for such a process requires that

there be an abiding knower going through all the successive steps.

Further, "After one [who has never seen a buffalo] has received the

instruction that a buffalo is similar to a cow from a forester and seen an

animal in the forest similar to the cow, one learns [for the first time] the

name of that as the result-since upamana is such, it would be impossi-

ble if the knower were different" (ibid., p. 15). Finally, "Hearing the letters

in succession, understanding the word-meanings (padarthagraha) by way

of remembering the semantic connections (samayasm.rty), reviewing

the word-meanings (tadalocanam) with the help of their impressions

at the time of apprehending the last letter (tatsamskarajam antyavar-

nakalanakale), understanding the meaning of the sentence as a whole

(vakyarthasampindanam) by means of the syntactic and other relation-

ships (akamrksadinibandhananvayakrtam)-all these would be extremely

difficult to explain without the selfsame knower" (ibid., p. 15). In other

words, linguistic communication presupposes an abiding knower, for

understanding the meaning of a word requires the synthesis of the letters

heard in succession, and understanding the meaning of a sentence re-

quires the synthesis of the word-meanings grasped in succession.

In the Buddhist version of the no-ownership theory, there is not only

Kisor Kumar

no permanent self, but, moreover, each internal state (in conformity withChakrabarti

Chandana

the general doctrine of momentariness applying to all reals) is strictly Chakrabarti

487

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

momentary. Each internal state endures for exactly one moment and

ceases to exist in the following moment. Each preceding state, however,

serves as the cause of the succeeding state, and thus the entire stream

(santana) of momentary states is linked by an unbroken causal chain.

Faced with the difficulty of accounting for memory and such acts as

recognitive perception, synthesis of word meanings, and so forth, which

presuppose memory, the Buddhist has responded as follows. Since the

stream is linked by an unbroken causal chain, the momentary state to

which the original experience belonged is able to produce an impression

of the experience in the succeeding state, which in its turn is able to

produce another impression in the next state, and so on. In this way the

impression of any previous experience may be passed on to any later

member of the same stream. Hence any later member of the stream

possessing the impression of the original experience may be able to

remember the same in spite of being different from the earlier state

having the experience. The impressions required in such an explanation

are certainly far more numerous than those required in the theory of

an abiding self. In this respect the Buddhist theory is bound to be less

economical. But the Buddhist is not perturbed by such proliferation in

the number of entities, for this is an inevitable consequence of the

doctrine of momentariness to which the Buddhist is already committed

on independent grounds.

One problem in this view, however, is that since the Buddhist cannot

fall back on a permanent entity like the brain or the body as the material-

ist can, he must suppose that every momentary internal state will have a

successor so that any discontinuity in the causal chain is avoided. The

claim that every momentary internal state has a successor (until at least

attaining nirvana, and even after attaining nirvana, according to some

Buddhists) has, from the Nyaya-Vaisesika point of view, all the appear-

ance of a forced solution. For one thing, the Buddhist must maintain that

even when a person is sound asleep and not dreaming, the momentary

internal states continue to be generated ceaselessly. The Nyaya-Vaisesika

philosophers find this to be nothing more than an ad hoc assumption, for

there is no evidence to prove that any actual cognitive or noncognitive

internal state is produced during dreamless sleep. The difference be-

tween the Nyaya view and the Buddhist view on this point is clear. For

the former, all that needs to be maintained is that the impressions of past

experiences continue to exist as dispositions. But the latter must hold

that actual, and not merely dispositional, internal states are generated

continuously even during dreamless sleep, and that each such state is

capable of performing the role of being the cause of the succeeding

state. In this respect the ontological burden of the Nyaya view turns out

Philosophy East & West to be lighter.

488

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

It may further be asked what kind of mental states could be plausibly

said to be uninterruptedly generated (and destroyed) during dreamless

sleep. Such states could not be those of pleasure, pain, awareness of any

object, and so forth, for then the question would be: if these were

actually produced during dreamless sleep (susupti), why does not any-

one ever come to know of their occurrence? One suggestion advanced

by some Buddhists is that these are purely subjective states of I-

consciousness (alayavijinana) which are formless (nirakara) as well as non-

intentional (nirvisayaka). Now the admission of nonintentional states of

consciousness may be welcome from the Buddhist point of view, particu-

larly from that of the Yogacara school. But to the Nyaya-Vaisesika philos-

ophers this is objectionable, for according to them all cognitive states are

intentional (savisayaka). Further, the supposition that self-consciousness

persists (albeit as a series of momentary states) in a dreamless sleep virtu-

ally amounts to a departure from the original spirit of the no-ownership

theory and brings it dangerously close to the theory of a permanent self.

Finally, a crushing objection has been succinctly stated in the following

passage.

If momentary, what has, been experienced long ago cannot be remembered,

for the cognizers are different. If it is said that what was experienced by an

earlier momentary state may be remembered by a later state because of their

being related as cause and effect, this is inappropriate. If there were no self,

the relation of cause and effect could not be ascertained. The cognitive state

which would be the effect is yet to come into being when the cognitive state

which is the cause is there, and by the time the former comes into being, the

latter ceases to be. Since there is no knower other than these two which

remains the same, how could it be known that these two successive entities

are related as cause and effect? It may be suggested that the earlier state

which is self-revealing also becomes aware of its nature as the cause which

is non-different from itself; similarly the self-cognizing later state also be-

comes aware of the fact of its being the effect which is non-different from

itself.... But this is an undue fabrication. Each of the two earlier and the later

cognitions is confined to itself; how then could the awareness that I am the

effect of this or the awareness that I am the cause of that take place? The fact

is that each is ignorant about the other.14

In brief, cognition of succession has to be distinguished from succes-

sion of cognition (which may remind one of a well-known argument of

Kant); the former cannot be accounted for without an abiding knower.

To conclude: we have explained how the Nyaya-Vaisesika philoso-

phers have argued for the theory of self as an abiding, noncorporeal Kisor Kumar

substance and defended their view against both the Carvaka materialists Chakrabarti

and the Buddhist no-ownership theorists. The discussion is by no means Chandana Chakrabarti

489

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

comprehensive. A fuller account would have to include copious refer-

ences to such works as Udayana's Atmatattvaviveka (tenth century

A.D.).15 It is hoped nevertheless that the discussion would provide food for

the thought of contemporary philosophers of mind although not many

of them support the theory of self as a permanent, immaterial substance.

NOTES

1 - Gotama is the reputed author of the Nyayasutra (sixth/fifth

B.C.). Since it is written in an aphoristic style, it has to be read wi

commentary of Vatsyayana called the Bhasya (second century

For these dates see U. Misra, History of Indian Philosophy,

(Allahabad: Tirabhukti Publications, 1966), pp. 25-36. Both o

works have been translated into English by Gr. Jha (Poona: O

Book Agency, 1939).

2 - This entire discussion applies only to individual, nonliberated

3 - Vatsyayana is the famous commentator on the Nyayasu

note 1.

4 - Nyayadarsanam of Gotama with Vatsyayana's Bha.sya, Uddyotaka-

ra's Varttika, Vacaspati Misra's Tatparvatika and Visvanaatha's Vrtti,

ed. Taranatha Nyaya-Tarkatirtha and Amarendramohan Tarkatirtha,

2d ed. (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal, 1985) (abbreviated as

Nyayadarsanam), pp. 156-157.

5 - Ibid., p. 157. Uddyotakara's Nyayavarttika (sixth century A.D.) has

been translated into English by Gr. Jha, Indian Thought (Allahabad:

E. J. Lazarus & Co., 1910-1920).

6 - Ibid., p. 157. A portion of of Vacaspati Misra's Tatparyatika has been

translated into English by T. Stcherbatsky, Buddhist Logic, vol. 2 (New

York: Dover, 1962).

7 - Vaisesikasutropaskara of Sankara Misra with the Prakasika Hindi com-

mentary by Dhundiraja Sastri, ed. Narayana Misra (Varanasi: Chow-

khamba Sanskrit Series Office, 1969), pp. 239-240.

8 - Ibid., p. 241

9- Padarthadharmasa.mgraha of Prasastapada with the Nyayakandaff

of Sridhara, ed. Durgadhar Jha (Varanasi: Benares Sanskrit University,

1963), p. 173.

10 - Nyavamanjarnof Jayanta Bhatta, ed. Surya Narayana Sukla (Varanasi:

Philosophy East & West Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office, 1936), pt. 2, p. 12.

490

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

11 -Ibid., p. 10.

12 - Vaisesikasutropaskara, p. 242; also Karikavali with Siddhantamukta-

vali, Prabha, Manjusha, DinakarTya, Ramarudrfya, and Gaigaramaja-

tiya, ed. C. Sankara Rama Sastry (Madras: Sri Balamanorama Press,

1923), pp. 386-387.

13 - Ibid., p. 410.

14- Padarthadharmasa.mgraha, pp. 170-171.

15 - One of Udayana's works, namely, Nyayakusumanjali, has been trans-

lated into EngLish by E. B. Cowell (Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press,

1864).

Kisor Kumar

Chakrabarti

Chandana Chakrabarti

491

This content downloaded from

152.58.115.38 on Sun, 24 Mar 2024 11:46:21 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Alchemy Air Element Theoricus and The JoDocument41 pagesAlchemy Air Element Theoricus and The JoElena ENo ratings yet

- An Explanation of The Translation of The Nasadiya Sukta (Hymn 10.129 of The Rigveda) by Kant SinghDocument3 pagesAn Explanation of The Translation of The Nasadiya Sukta (Hymn 10.129 of The Rigveda) by Kant SinghAnamika100% (1)

- A Primer of Theosophy A Very Condensed Outline (1909)Document138 pagesA Primer of Theosophy A Very Condensed Outline (1909)Joma SipeNo ratings yet

- Acrylic SecretsDocument92 pagesAcrylic SecretsMihaela Toma100% (2)

- Science in Ancient IndiaDocument19 pagesScience in Ancient IndiasujupsNo ratings yet

- Assignment HBEF3703 Introduction To Guidance and Counselling / May 2020 SemesterDocument8 pagesAssignment HBEF3703 Introduction To Guidance and Counselling / May 2020 SemesterSteve SimonNo ratings yet

- Sadhan Samar Part 1 of 3Document209 pagesSadhan Samar Part 1 of 3arupam sanyal100% (1)

- Dharmakirti:refutation of Theism PDFDocument35 pagesDharmakirti:refutation of Theism PDFnadalubdhaNo ratings yet

- Dharmakirti:Refutation of TheismDocument35 pagesDharmakirti:Refutation of TheismnadalubdhaNo ratings yet

- Physical Concepts in The Samkhya and VaisesDocument32 pagesPhysical Concepts in The Samkhya and Vaisesitineo2012No ratings yet

- Charvaka Philosophy - KV ThomasDocument15 pagesCharvaka Philosophy - KV ThomasPhiloBen Koshy100% (1)

- Kanada's Vaisheshika Vs Modern Particle PhysicsDocument18 pagesKanada's Vaisheshika Vs Modern Particle PhysicsE100% (1)

- Is Space Created? Reflections On Akara's Philosophy and Philosophy of PhysicsDocument18 pagesIs Space Created? Reflections On Akara's Philosophy and Philosophy of PhysicsKaalaiyanNo ratings yet

- Indian Physics: Outline of Early HistoryDocument36 pagesIndian Physics: Outline of Early Historydas_s13No ratings yet

- Spiritual Background of Vedic Astrology by Patraka Das PDFDocument26 pagesSpiritual Background of Vedic Astrology by Patraka Das PDFdoors-and-windows100% (1)

- The Little Blue Book On SchedulingDocument105 pagesThe Little Blue Book On Schedulingparagjain007No ratings yet

- Conceiving the Inconceivable Part 2: A Scientific Commentary on Vedānta Sūtras: Six Systems of Vedic Philosophy, #2From EverandConceiving the Inconceivable Part 2: A Scientific Commentary on Vedānta Sūtras: Six Systems of Vedic Philosophy, #2No ratings yet

- Jain EthicsDocument37 pagesJain Ethicssantanu6No ratings yet

- Henry Stapp ReportDocument53 pagesHenry Stapp Reportaexb123No ratings yet

- Sad-Darshana-Six Systems of Vedic PhilosophyDocument77 pagesSad-Darshana-Six Systems of Vedic Philosophyraj100% (3)

- Darshana PhilosophyDocument9 pagesDarshana PhilosophyIgor OozawaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy and Physics: August 2015Document13 pagesPhilosophy and Physics: August 2015Mauricio JullianNo ratings yet

- Ontology in HinduismDocument10 pagesOntology in HinduismAdrian MunteanuNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of Panchabhootha Sidhantha PDFDocument6 pagesCritical Analysis of Panchabhootha Sidhantha PDFkirushnenNo ratings yet

- 48 SPJMR 996.fDocument9 pages48 SPJMR 996.f21189207No ratings yet

- Ayurveda ThoreyDocument15 pagesAyurveda ThoreyanantNo ratings yet

- Unit-2 Vaisesika Philosophy PDFDocument12 pagesUnit-2 Vaisesika Philosophy PDFkaustubhrsingh100% (1)

- A History of CarvakasDocument28 pagesA History of Carvakasবিশ্ব ব্যাপারীNo ratings yet

- Materialist Philosophy in Ancient IndiaDocument10 pagesMaterialist Philosophy in Ancient IndiaBarbara LitoNo ratings yet

- Observations On Yogipratyaka PDFDocument19 pagesObservations On Yogipratyaka PDFGeorge PetreNo ratings yet

- HS 301 - Part - 4.3 - 2023 - by CDSDocument5 pagesHS 301 - Part - 4.3 - 2023 - by CDSbhavikNo ratings yet

- Art 1Document6 pagesArt 1haihum741No ratings yet

- Indian Physics: Outline of Early History: Subhash Kak February 2, 2008Document36 pagesIndian Physics: Outline of Early History: Subhash Kak February 2, 2008danda1008716No ratings yet

- IGNTU Econtent 369570220670 BA AIHC 6 DrJanardhanaB ScienceandTechnologyinAncientIndia AllDocument141 pagesIGNTU Econtent 369570220670 BA AIHC 6 DrJanardhanaB ScienceandTechnologyinAncientIndia AllRashmiNo ratings yet

- Metaphysics - WikipediaDocument23 pagesMetaphysics - WikipediaDiana GhiusNo ratings yet

- Theo Assignment 1 Hindu PhilosophiesDocument18 pagesTheo Assignment 1 Hindu PhilosophiesPooja GyawaliNo ratings yet

- Creation, Its Processes, and Significance: Samkhya - Evolution and InvolutonDocument10 pagesCreation, Its Processes, and Significance: Samkhya - Evolution and InvolutonDheeren999No ratings yet

- Substancce View - Final Text-2003 WORDDocument110 pagesSubstancce View - Final Text-2003 WORDJayakumar KumarNo ratings yet

- What Is Token Physicalism?: AbstractDocument21 pagesWhat Is Token Physicalism?: Abstracttenzin hyuugaNo ratings yet

- Section IV Philosphic, Pauranic and Early Bhakti PeriodDocument10 pagesSection IV Philosphic, Pauranic and Early Bhakti PeriodMammen JosephNo ratings yet

- Farrell Jainismgeneralsemantics 1959Document7 pagesFarrell Jainismgeneralsemantics 1959wacuchnaNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Vaiśe Ika Philosophy: 2.0 ObjectivesDocument13 pagesUnit 2 Vaiśe Ika Philosophy: 2.0 ObjectivesShraddhaNo ratings yet

- Concept of Atomism According To Bauddha Philosophy - DR M K SridharDocument7 pagesConcept of Atomism According To Bauddha Philosophy - DR M K SridharJohn KAlespiNo ratings yet

- Indian Cosmological IdeasDocument12 pagesIndian Cosmological IdeasHrishikesh BhatNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Satkāryavāda and Sā Kya MetaphysicsDocument13 pagesAn Analysis of Satkāryavāda and Sā Kya MetaphysicsBest ProductionNo ratings yet

- Cosmology Through Prism of Science & JainismDocument4 pagesCosmology Through Prism of Science & JainismSanjay SanghviNo ratings yet

- Categories in Śrī Madhva's DvaitaDocument8 pagesCategories in Śrī Madhva's DvaitaAnonymous gJEu5X03No ratings yet

- Além Da MenteDocument146 pagesAlém Da Menteandy zNo ratings yet

- On The Connexion Between Indian and Greek Philosophy - Richard Garbe (1894)Document19 pagesOn The Connexion Between Indian and Greek Philosophy - Richard Garbe (1894)Đoàn DuyNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 3: How The Acharyas Have Developed The Vedantic ThoughtDocument83 pagesChapter - 3: How The Acharyas Have Developed The Vedantic ThoughtB.venkateswarluNo ratings yet

- History of Indian Physical and Chemical Thought: Subhash KakDocument25 pagesHistory of Indian Physical and Chemical Thought: Subhash Kaksiddharth deshwalNo ratings yet

- Title: The Ontology of "Corporeal" - Nyaya-Vaisesika View PointDocument7 pagesTitle: The Ontology of "Corporeal" - Nyaya-Vaisesika View PointronNo ratings yet

- Vaisaketu StrutaDocument39 pagesVaisaketu StrutaAnkit ZaveriNo ratings yet

- Samkhya and VaisesikaDocument10 pagesSamkhya and Vaisesika17EEDSP LABNo ratings yet

- Gauvain Time Indian BuddhismDocument21 pagesGauvain Time Indian BuddhismChris GolightlyNo ratings yet

- 3 Praman Indian Philo ThougtsDocument54 pages3 Praman Indian Philo ThougtsSudip ChakravorttiNo ratings yet

- Theory of Causation - Nyaya VaisheshikaDocument48 pagesTheory of Causation - Nyaya VaisheshikaVikram BhaskaranNo ratings yet

- Outlines of The Lecture:: V (VA) PDocument33 pagesOutlines of The Lecture:: V (VA) PTanviNo ratings yet

- Suarez - UTS First SessionDocument12 pagesSuarez - UTS First SessionAJ Grean EscobidoNo ratings yet

- Religious Experience in The Hindu TraditionDocument12 pagesReligious Experience in The Hindu TraditionEscri BienteNo ratings yet

- Quadrants of the Corporeal: Reflections On the Foundations of ExperienceFrom EverandQuadrants of the Corporeal: Reflections On the Foundations of ExperienceNo ratings yet

- Vidyas in The Upanishads0A by V. NagarajanDocument5 pagesVidyas in The Upanishads0A by V. NagarajanAnamikaNo ratings yet

- Cited As H. L. A. Hart, Was A British Legal Philosopher, and A Major FigureDocument4 pagesCited As H. L. A. Hart, Was A British Legal Philosopher, and A Major FigureAnamikaNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology of Spirit: Hegel's Dialectic MethodDocument10 pagesPhenomenology of Spirit: Hegel's Dialectic MethodAnamikaNo ratings yet

- Desire ....Document2 pagesDesire ....AnamikaNo ratings yet

- Mitchell Gold +bob WilliamsDocument43 pagesMitchell Gold +bob Williamsrakhmi fitrianiNo ratings yet

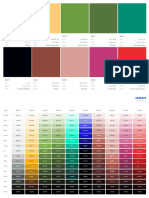

- Color 1 Color 2 Color 3 Color 4 Color 5: RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk NameDocument4 pagesColor 1 Color 2 Color 3 Color 4 Color 5: RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk Name RGB Cmyk NameValentina TorresNo ratings yet

- Social Sciences-Grade 9 Geography Worksheet May 2020Document7 pagesSocial Sciences-Grade 9 Geography Worksheet May 2020agangdayimaniNo ratings yet

- Control Systems Prof. C. S. Shankar Ram Department of Engineering Design Indian Institute of Technology, Madras Lecture - 40 Root Locus 4 Part-2Document7 pagesControl Systems Prof. C. S. Shankar Ram Department of Engineering Design Indian Institute of Technology, Madras Lecture - 40 Root Locus 4 Part-2HgNo ratings yet

- LampiranDocument26 pagesLampiranSekar BeningNo ratings yet

- Kunal RawatDocument4 pagesKunal RawatGuar GumNo ratings yet

- 9037HG32LZ20: Product DatasheetDocument2 pages9037HG32LZ20: Product DatasheetNarcisse AhiantaNo ratings yet

- EAC MANUAL 2012 - Best Practices On Accreditation: Siti Hawa HamzahDocument69 pagesEAC MANUAL 2012 - Best Practices On Accreditation: Siti Hawa HamzahSharmin Ahmed TinaNo ratings yet

- DEVICE Exp 4 StudentDocument4 pagesDEVICE Exp 4 StudentTouhid AlamNo ratings yet

- Manual Call Points: GeneralDocument2 pagesManual Call Points: GeneralAnugerahmaulidinNo ratings yet

- MDA Report Tata Industries FY20 21Document6 pagesMDA Report Tata Industries FY20 21Darshan VadherNo ratings yet

- Lab #2: PI Controller Design and Second Order SystemsDocument4 pagesLab #2: PI Controller Design and Second Order SystemssamielmadssiaNo ratings yet

- Oxford - University - ResearchDocument9 pagesOxford - University - ResearchJagat KarkiNo ratings yet

- JD v7 Id1143bbDocument3 pagesJD v7 Id1143bbShaileshNo ratings yet

- 2 EEE - EPM412 Load CCs 2Document30 pages2 EEE - EPM412 Load CCs 2Mohamed CHINANo ratings yet

- A Study On Financial Performance Analysis With Reference To TNSC Bank Chennai Ijariie10138Document7 pagesA Study On Financial Performance Analysis With Reference To TNSC Bank Chennai Ijariie10138Jeevitha MuruganNo ratings yet

- Problem PDFDocument2 pagesProblem PDFEric ChowNo ratings yet

- 1 DTU Assistant ProfessorDocument22 pages1 DTU Assistant ProfessorTOUGHNo ratings yet

- Group One: David, Hegel, Carlos, Jay, Jenni, Yvette, GingerDocument40 pagesGroup One: David, Hegel, Carlos, Jay, Jenni, Yvette, GingerFederico FioriNo ratings yet

- ATV61 Communication Parameters en V5.8 IE29Document126 pagesATV61 Communication Parameters en V5.8 IE29Anonymous kiyxz6eNo ratings yet

- Coral Reef Restoration A Guide To EffectDocument56 pagesCoral Reef Restoration A Guide To EffectDavid Higuita RamirezNo ratings yet

- Emailing Teacher Notes PDFDocument2 pagesEmailing Teacher Notes PDFSylwia WęglewskaNo ratings yet

- ExperimentDocument8 pagesExperimentAlex YoungNo ratings yet

- Vulvovaginal InfectionDocument66 pagesVulvovaginal InfectionRadhika BambhaniaNo ratings yet

- Wilms Tumor Hank Baskin, MDDocument11 pagesWilms Tumor Hank Baskin, MDPraktekDokterMelatiNo ratings yet

- Biomedical Engineering Jobs in Gulf CountriesDocument2 pagesBiomedical Engineering Jobs in Gulf CountriesramandolaiNo ratings yet

- Summative Test-Quarter 2Document19 pagesSummative Test-Quarter 2JocelynNo ratings yet