0% found this document useful (0 votes)

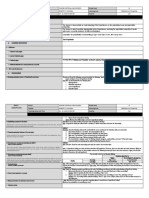

30 views9 pagesLesson Log: Hypothesis Testing in Statistics

This document outlines the daily lesson plan for a Statistics and Probability class, focusing on hypothesis testing. It includes objectives, content standards, performance standards, learning competencies, and detailed procedures for teaching concepts such as null and alternative hypotheses, level of significance, and types of errors. The lesson is structured to engage students through activities, discussions, and formative assessments to enhance their understanding of statistical inference in real-life contexts.

Uploaded by

Angel May AndresCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

30 views9 pagesLesson Log: Hypothesis Testing in Statistics

This document outlines the daily lesson plan for a Statistics and Probability class, focusing on hypothesis testing. It includes objectives, content standards, performance standards, learning competencies, and detailed procedures for teaching concepts such as null and alternative hypotheses, level of significance, and types of errors. The lesson is structured to engage students through activities, discussions, and formative assessments to enhance their understanding of statistical inference in real-life contexts.

Uploaded by

Angel May AndresCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd