0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views36 pagesUnderstanding Electronic Switches in Power Electronics

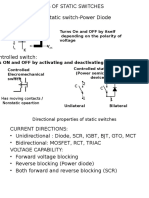

The document discusses power electronics and electronic switches. It describes ideal switches and practical switches. It covers semiconductor basics and classifications of power switches. It also discusses diodes and how pn junctions are formed in semiconductor materials.

Uploaded by

Abdullah KhanCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

0% found this document useful (0 votes)

15 views36 pagesUnderstanding Electronic Switches in Power Electronics

The document discusses power electronics and electronic switches. It describes ideal switches and practical switches. It covers semiconductor basics and classifications of power switches. It also discusses diodes and how pn junctions are formed in semiconductor materials.

Uploaded by

Abdullah KhanCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PPTX, PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd