Professional Documents

Culture Documents

9 Isometric Drawings

Uploaded by

Junior MirandaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

9 Isometric Drawings

Uploaded by

Junior MirandaCopyright:

Available Formats

Isometric Drawings

ISOMETRIC DRAWINGS

Introduction

Isometric drawings are a type of pictorial drawings that show the three principal dimensions of an object in

one view. The principal dimensions are the limits of size for the object along the three principal directions.

Pictorial drawings consist of visible object faces and the features lying on the faces with the internal features

of the object largely hidden from view. They tend to present images of objects in a form that mimics what the

human eye would see naturally. Pictorial drawings are easy to understand since the images shown bear

resemblance to the real or imagined object. Non-technical personnel can interpret them because they are

generally easy to understand. Pictorial drawings are excellent starting point in visualization and design and

are often used to supplement multiview drawings. Hidden lines are usually omitted in pictorial drawings,

except where they aid clarity.

An isometric drawing is one of three types of axonometric drawings they are created based on parallel

projection technique. The other two types of axonometric drawings are dimetric and trimetric drawings. In

isometric drawings, the three principal axes make equal angles with the image plane. In dimetric drawing,

two of the three principal axes make equal angles with the image plane while in trimetric drawing; the three

principal axes make different angles with the image plane. Isometric drawings are the most popular.

Isometric Projection and Scale

o

o

An isometric projection is a representation of a view of an object at 35 16 elevation and 45 azimuth. The

o

principal axes of projection are obtained by rotating a cube through 45 about a vertical axis, then tilting it

o

o

downward at 35 16 (35.27 ) as shown in Fig. 1a. A downward tilt of the cube shows the top face while an

o

o

upward tilt shows the bottom face. The 45 rotation is measured on a horizontal plane while the 35 16 angle

is measured on a vertical plane. The combined rotations make the top diagonal of the cube to appear as a

point in the front view. The nearest edge of the cube to the viewer appears vertical in the isometric view. The

o

two receding axes project from the vertical at 120 on the left and right sides of the vertical line as shown in

o

Fig. 1b. The three principal axes are therefore inclined at 120 and are parallel to the cube edges in the

isometric view. These three principal axes are known as isometric axes. The two receding axes are inclined

o

o

at 30 to the horizontal line while the vertical axis is at 90 to the horizontal line. The three visible faces of the

cube are on three planes called isometric planes or isoplanes. The Lines in an object parallel to the isometric

axes are referred to as isometric lines while lines not parallel to them are known as non-isometric lines.

Isometric projection is not the most pleasant to the human eye but it is easy to draw and dimension.

a) Isometric rotations

b) Isometric axes in image plane

Fig. 1 Isometric projection

o

The regular axis is usually inclined at 45 but the receding axes in an isometric projection are inclined at 30

to the horizontal. Hence there is a difference in orientation between the receding isometric axis and the

regular axis. These orientations of axes are shown in Fig. 2. where a measurement of 10 units along the

regular axis projects to 8.16 units on the isometric axis. Thus one unit of measurement on the regular axis is

equal to 0.816 on the isometric scale. This means that a regular length of one unit must be scaled to 0.816

units in an isometric projection.

Osakue, E.

Isometric Drawings

Now isometric projection is a true or accurate

representation of an object on the isometric

scale or measurement along the isometric axes.

This is about 18% short of the actual dimensions

of the object. In practice, a regular length of one

unit is drawn as one unit on the isometric axis,

thus introducing some error to the projection.

Hence, the actual images of object shown in

isometric views are, therefore, called isometric

drawings and not isometric projections. The

main difference between an isometric projection

and an isometric drawing is size. The drawing is

slightly larger than the projection because it is

full scale. Features in isometric drawings may be

created on isometric planes or non-isometric

planes. For features on non-isometric planes,

creating them on isometric planes and then

projecting to non-isometric planes will be found

very helpful during construction of isometric

drawings.

Fig. 2 Isometric scale

Types of Isometric Drawings

Isometric axes can be positioned in different ways to obtain different isometric views of an object. Three

basic views are in general use and they are regular isometric, reverse isometric and long-axis isometric as

shown in Fig. 3. In regular isometric, the viewer looks down on the object so the top of the object is revealed.

o

The receding axes are drawn up from the horizontal at 30 with the nearest lower end at the base of the Bbox, see Fig. 3a. This is the most common type of isometric drawing. The viewer in reverse isometric is

looking up at the bottom of the object so this view reveals the bottom of the object. The receding axes are

o

drawn downward from the horizontal at 30 with the back lower end at the base of the B-box, see Fig. 3b.

The long-axis isometric keeps the axis of the object horizontal and is normally used for objects with length

considerably larger than the width or depth. The viewpoint could be from the left or right side but the long

o

axis is drawn horizontal and the others are drawn at 60 as indicated in Fig. 3c. The long-axis isometric is the

least used.

a) Regular

b) Reverse

c) Long-axis

Fig. 3 Types of isometric drawings

Constructing Isometric Arcs and Circles

Arcs and circles are common features on objects, especially in mechanical design and drafting. Isometric

arcs are portions of isometric circles which are ellipses on isometric planes. Fig. 4 shows a component with

isometric arcs on the right face or right isoplane. Since the arcs are portions of isometric circles, the

technique for creating isocircles will be discussed. It is worth noting that an isometric arc can be constructed

without creating a full isometric circle. One important rule to remember when creating curves in isometric

projection is that the isometric face or plane the curves lie on should be created first using guide or

Osakue, E.

Isometric Drawings

construction lines. Then the curves can be created using projection of key points and intersection of

projection lines from the key points. A second rule is that true dimensions are transferred to non-isoplanes.

Hence where there are inclined and oblique faces, the true sizes of features on the auxiliary views should be

used during construction. As mentioned earlier, isometric circles are ellipses and commonly called isocircles.

There are several techniques available for creating isocircles, but the easiest and more popular one is the

four-center ellipse. This technique will be used here to create the three basic isometric circles: top isocircle,

left (front) circle, and right circle. The four-center ellipse is an approximate ellipse but it is usually good

enough for most drafting applications. Fig. 5 shows in five steps, the creation of the top isocircle.

Fig. 4 Isometric arcs

Fig.5a Constructing top isocircle

Step 1: Draw a square using the circle diameter as size

For the top isocircle, the top isoplane is the right surface to draw the square. The top isoplane is

horizontal as can be seen in step 1 of Fig. 5a. Draw the isometric square.

Step 2: Draw the center lines of the square

Draw the two center lines of the square as shown in Step 2 of Fig. 5a.

Step 3: Draw the big arcs of the isocircle

Identify the key points K1 and K2. These are two centers of the four center ellipse technique. Notice

that these centers are located at the obtuse angle corners of the isometric square. Using the radius

R, with centers at K1 and K2 draw the two big arcs for the isocircle as shown in Step 3 of Fig. 5a.

Step 4: Locate the centers of the small arcs of the isocircle

Draw the diagonal K3-K4 between the acute angle corners of the square in Fig. 5a. Then draw lines

K1-K5 and K2-K6. The intersection (K7) of the lines K3-K4 and K1-K5 in Step 5 locates one center

for a small arc. The other small arc center is located at K8, the intersection of lines K3-K4 and K2K6.

Step 5: Draw the small arcs of the isocircle

Using the centers of the small arcs K7 and K8, draw the two small arcs of radius r, as shown in Step

5 of Fig. 5a. Verify that the big and small arcs are tangent to the isometric square. If a CAD package

is used, circles could be drawn instead of arcs. The circles must then be trimmed to obtain the arcs

required in the isocircle.

Fig.5b Constructing top isocircle

Osakue, E.

Isometric Drawings

The five steps described above for drawing the isocircles could be reduced to three as shown in Fig. 5b by

combining steps 1 and 2 as Step 1 and combining steps 3 (without drawing the large arcs) and 5 as Step 3.

This leaves Step 4 above as the new Step 2 in which all the key points K1 to K8 are created. The centers of

the four arcs can then be identified as K1, K2, K7, and K8. In the last step (new Step 3), the four arcs are

created as shown in fig. 5b. Fig. 6 and Fig. 7 show, respectively, in five steps how the left and right isocircles

can be created. These steps are the same as described above in Fig. 5a for the top isocircle, except that the

isoplanes are respectively the left and right ones. Again, these five steps could be reduced to three steps,

see Fig. 5b.

Fig. 6 Constructing left isocircle

Fig. 7 Constructing right isocircle

The construction of isometric arcs follows the same steps as isocircles. However, simple visual inspection of

the arc in a problem will reveal which quadrant(s) the arc is located in. Quarter arcs and half circle arcs are

quite common in mechanical drafting. For example, Fig. 4 has a quarter arc on one of the acute angle

corners, requiring the construction one of the small radius arcs in an isocircle.

Construction Techniques for Isometric Drawing

It is quite easy creating isometric lines on isometric planes. This is done by drawing the lines parallel to

isometric axes. However, creating non-isometric lines and angles must be done with care. In general, angles

of non-isometric lines are drawn by creating line segments between the end points of the locations that form

the angle. On isometric planes, circles in principal orthographic views turn to isometric ellipses and arcs

appear as partial isometric ellipses as discussed in the previous section. Irregular curves are created from

intersections of projection lines on isometric planes.

There are two techniques generally used for isometric drawings. These are the box and the centerline layout

techniques, but the box technique is the most common construction technique. The box technique is also

known as the coordinate technique. In the approach, a bounding (B-) box is first made with guide lines using

the principal dimensions object. The principal dimensions may be designated as W for width, H for height,

and D for depth. It may be necessary to add up dimensions along the principal axes to get the principal

dimensions of an object. The faces on the objects are then created after the B-box is ready. Each feature on

the object is properly located and created within the B-box. This technique is good for drawing objects with

angular and radial features or objects that have irregular shapes or form. The general steps in the box

technique are:

1.

Define the origin of and create the isometric axes

2.

Create the bounding box using the principal dimensions

3a.

Use dimensions from top and front view to mark out faces

3b.

Or use dimensions from top and side views to mark out faces

4.

Locate and create all features on the faces

5.

Finish and check the drawing

Applications of the Box Techniques

In this section, the box technique will be used to create isometric views of different typical objects as

illustrations. These include objects with normal faces, inclined faces, oblique faces, and irregular curves. As

pointed above for isocircles, the number steps used here could be reduced as one develops proficiency in

the technique. The activities could be done using freehand sketching or with CAD software on a computer.

Osakue, E.

Isometric Drawings

A) Object with Normal Faces

Fig. 8 shows the construction of the isometric drawing of an object with normal faces. The multiview drawing

of the object is shown in Fig. 8a. Note that Step 4 in the general procedure is not needed for this object.

Steps 1 and 2 of the general procedure can be combined into one by drawing the B-box directly keeping the

isometric axes direction in mind.

Fig. 8 Box method for normal faces

B) Object with Inclined Faces

Fig. 9 shows the construction of the isometric drawing of an object with inclined face. The multiview drawing

of the object is shown in Fig. 9a. Note that Step 4 in the general procedure requires the creation of an

isometric circle on the inclined face.

Fig. 9 Box method for inclined face

Osakue, E.

Isometric Drawings

C) Object with Oblique Faces

Fig. 10 shows the construction of the isometric drawing of an object with oblique face. The multiview drawing

of the object is shown in Fig. 10a. Step 4 in the general procedure is not required in this object.

Fig. 10 Box method for oblique face

D) Object with Angled Faces

Fig. 11 shows the construction of the isometric drawing of an object with angled faces. The multiview

drawing of the object is shown in Fig. 11a. By inspection of the multiview drawing, it is clear that the right

vertex on the top view is at the midpoint of the depth dimension D. This helps in locating the vertex on the Bo

box without using trigonometry. Observe that with the front angle of 30 and the dimensions W and W1

given, the dimension H1 would not be shown. So H1 must then be calculated using trigonometry. It can be

o

shown that: H1 = H (W W1)xtan30 . Thus the lines defining the angles on the object can be created on

o

o

the B-box without actually measuring the angles 60 and 30 . Always remember that angles on an object are

not directly measured in isometric construction. They are used to calculate the end points of lines defining

the angles. Finally, note that Step 4 in the general procedure is not required in this object.

Fig. 11 Box method for angles

amples of isoplanes in other axonometric projections

Osakue, E.

You might also like

- Making An Isometric Drawing.1Document23 pagesMaking An Isometric Drawing.1kurt wellsNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4: Isometric and ObliqueDocument28 pagesChapter 4: Isometric and Obliquehisham_eyesNo ratings yet

- ISOMETRICDocument39 pagesISOMETRICKaustubh MallikNo ratings yet

- HiggsPWaghidY 2017 PhilosophicalConceptu ReaderInPhilosophyOfEDocument4 pagesHiggsPWaghidY 2017 PhilosophicalConceptu ReaderInPhilosophyOfELerato MakgobatheNo ratings yet

- Unit-5 Isometric & Orthographic ProjectionsDocument57 pagesUnit-5 Isometric & Orthographic ProjectionskavyaNo ratings yet

- Handout 3 ProjectionsDocument5 pagesHandout 3 ProjectionsTelen fosterNo ratings yet

- 7concept of Isometric 1Document46 pages7concept of Isometric 1Sya EyraNo ratings yet

- Multiview Drawings: Unit 5Document14 pagesMultiview Drawings: Unit 5Nur SidikNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Isometric DrawingsDocument10 pagesIntroduction To Isometric Drawingsbarnibar1No ratings yet

- Basic Tec 2Document36 pagesBasic Tec 2TMTM MediaNo ratings yet

- Overview of 1st Angle and 3rd AngleDocument14 pagesOverview of 1st Angle and 3rd AngleM SureshNo ratings yet

- Importance of Engineering DrawingDocument3 pagesImportance of Engineering DrawingFarah DesitaNo ratings yet

- 4OTALLYDocument28 pages4OTALLYlino_borrotoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3-Multiview DrawingsDocument58 pagesChapter 3-Multiview DrawingsamdevaNo ratings yet

- Engineering DrawingDocument27 pagesEngineering Drawingjacob100% (1)

- Dr.R. GANESAMOORTHY.B.E.,M.E.,Ph.d. Professor - Mechanical Engineering Saveetha Engineering College, Tandalam, ChennaiDocument33 pagesDr.R. GANESAMOORTHY.B.E.,M.E.,Ph.d. Professor - Mechanical Engineering Saveetha Engineering College, Tandalam, ChennaitgpradeepNo ratings yet

- Isometric DrawingDocument22 pagesIsometric DrawingRachel Faith GarciaNo ratings yet

- Engineering Drawing SolutionsDocument20 pagesEngineering Drawing Solutionsmtkhusro92No ratings yet

- Sample Midterm Problems - Engineering Graphics in DesignDocument5 pagesSample Midterm Problems - Engineering Graphics in Designmaterial manNo ratings yet

- Cad Cam Lab Manual r16Document123 pagesCad Cam Lab Manual r16Praveen YadavNo ratings yet

- Technical Drawing PDFDocument71 pagesTechnical Drawing PDFrsalvasanNo ratings yet

- 3 View Orthographic DrawingDocument3 pages3 View Orthographic DrawingMuhammad FitriNo ratings yet

- DIMENSIONINGDocument32 pagesDIMENSIONINGnagamalleswarrao50% (2)

- Why Have 3D Printers in The ClassroomDocument2 pagesWhy Have 3D Printers in The Classroomjessy3008No ratings yet

- Instructional Materials On Academic Achievement in Agricultural SciDocument109 pagesInstructional Materials On Academic Achievement in Agricultural Scishyme1No ratings yet

- Engeering Graphic 1st YearDocument64 pagesEngeering Graphic 1st YearRajpurohit Samundra0% (1)

- Chapter 2 - Dimensioning - EGE4Document162 pagesChapter 2 - Dimensioning - EGE4bmyertekinNo ratings yet

- List of Mechanical Components of Engineering Drawing For Open Ended LabDocument2 pagesList of Mechanical Components of Engineering Drawing For Open Ended LabMuhammad KhalilNo ratings yet

- Effect of Virtual Analytical Chemistry Laboratory On EnchancingDocument25 pagesEffect of Virtual Analytical Chemistry Laboratory On EnchancingNiken WidyastutiNo ratings yet

- Angles of A PolygonDocument39 pagesAngles of A PolygonGabriel TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Mirror of Humanity - SummaryDocument2 pagesMirror of Humanity - Summaryrh 077No ratings yet

- Theory of Projection PDFDocument52 pagesTheory of Projection PDFSiddhrajsinh Zala100% (2)

- Computer Aided Engineering - PrabhakarDocument37 pagesComputer Aided Engineering - PrabhakarPrabhakar PurushothamanNo ratings yet

- Artifact ReflectionDocument3 pagesArtifact Reflectionapi-455790828No ratings yet

- Technical LetteringDocument12 pagesTechnical Letteringthrift flipNo ratings yet

- Drawing2 Module1Document9 pagesDrawing2 Module1Marcus Jacob JonsonNo ratings yet

- AutoCAD Syllabus FinalDocument7 pagesAutoCAD Syllabus FinalAnubhavNo ratings yet

- Technical DrawingDocument38 pagesTechnical DrawingKinfe MehariNo ratings yet

- EG Bridge CourseDocument45 pagesEG Bridge Coursekrunal07786No ratings yet

- Erase, Copy, Mirror, Offset, Array, Move, Rotate, Scale, Stretch, Lengthen, Trim, Extend, Break at Point, Break, Chamfer, Fillet, ExplodeDocument18 pagesErase, Copy, Mirror, Offset, Array, Move, Rotate, Scale, Stretch, Lengthen, Trim, Extend, Break at Point, Break, Chamfer, Fillet, ExplodeRida E ZahraNo ratings yet

- Course Code Course Title Date Effective: Date Revised: Prepared By: Approved By: Page No.Document3 pagesCourse Code Course Title Date Effective: Date Revised: Prepared By: Approved By: Page No.Idris Jeffrey MangueraNo ratings yet

- Orthographic Projection Lesson RevisedDocument87 pagesOrthographic Projection Lesson RevisedVictor M. MorcilloNo ratings yet

- Auto Cad FileDocument15 pagesAuto Cad FileabcdeNo ratings yet

- 2 Components of ResearchDocument46 pages2 Components of ResearchTiba AlaniNo ratings yet

- AxonometricDocument10 pagesAxonometricapi-250785889No ratings yet

- Wellcome To Basic Tech. Class Topic: Metal WorkDocument13 pagesWellcome To Basic Tech. Class Topic: Metal WorkEkemini-AbasiNo ratings yet

- Engineering Drawing: Mechanical Engineering Department L.J. PolytechnicDocument40 pagesEngineering Drawing: Mechanical Engineering Department L.J. PolytechnicTufel NooraniNo ratings yet

- Sectional OrthographicDocument80 pagesSectional OrthographicKrish Hams100% (1)

- Engineering Drawing Meng 2203: Teshome Bogale May 2021Document41 pagesEngineering Drawing Meng 2203: Teshome Bogale May 2021Abdi ZerihunNo ratings yet

- Orthographic ProjectionDocument108 pagesOrthographic ProjectionSrimanthula SrikanthNo ratings yet

- D & Engg Module 3Document44 pagesD & Engg Module 3vivek100% (1)

- 1 Engineering DrawingDocument4 pages1 Engineering DrawingRovil BeridoNo ratings yet

- Computer-Aided Drafting and Design (Cadd)Document10 pagesComputer-Aided Drafting and Design (Cadd)gilberthufana446877No ratings yet

- HND Mechatronics (NBTE)Document281 pagesHND Mechatronics (NBTE)Favour Uche ChukwuNo ratings yet

- Isometric DrawingsDocument27 pagesIsometric DrawingsMichael Martinez100% (1)

- Isometric DrawingsDocument29 pagesIsometric DrawingsJyotirmoy DekaNo ratings yet

- Isometric Drawings: (Perspectives)Document27 pagesIsometric Drawings: (Perspectives)nandhuNo ratings yet

- Engineering Drawing IsometricDocument16 pagesEngineering Drawing Isometricpanashezhou321No ratings yet

- Axonometric ProjectionDocument6 pagesAxonometric ProjectionSivaram NayakNo ratings yet

- InventoryDocument4 pagesInventorySiva KumarNo ratings yet

- Intrument Range ListDocument5 pagesIntrument Range ListSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- InventoryDocument4 pagesInventorySiva KumarNo ratings yet

- Daily Production Report December - 2019 (24.12.19)Document51 pagesDaily Production Report December - 2019 (24.12.19)Siva KumarNo ratings yet

- Planned Order TemplateDocument1 pagePlanned Order TemplateSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- SSP Pending Jobs SL No Points Responsible Target DateDocument2 pagesSSP Pending Jobs SL No Points Responsible Target DateSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- Unit ConversionDocument1 pageUnit ConversionSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- FileDocument2 pagesFileSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- Storage location-SCM: SL No Department Material Type Storage Location NameDocument3 pagesStorage location-SCM: SL No Department Material Type Storage Location NameSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- AMP Color Testing MethodDocument1 pageAMP Color Testing MethodSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- Additional Emergency Lighting Requirement in Plant Area: No. Location Point No PurposeDocument2 pagesAdditional Emergency Lighting Requirement in Plant Area: No. Location Point No PurposeSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- Technical Specifications: 50Hz Powered by Perkins SeriesDocument4 pagesTechnical Specifications: 50Hz Powered by Perkins SeriesSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- Plant Capacity 220 Heater Design DataDocument4 pagesPlant Capacity 220 Heater Design DataSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- SDS For Water Column OverheadDocument11 pagesSDS For Water Column OverheadSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- Final Project Report Plastic Bottle ManufactureDocument101 pagesFinal Project Report Plastic Bottle Manufactureaskaridumbo82% (33)

- Pet Polycondensation Side ReactionsDocument6 pagesPet Polycondensation Side ReactionsGeorge MarkasNo ratings yet

- Insane ProjectDocument220 pagesInsane ProjectsurajphilipsNo ratings yet

- School FormDocument3 pagesSchool FormSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- Haccp 06 PDFDocument13 pagesHaccp 06 PDFSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- 1 Solid State Polymerization of Poly Ethylene Terephthalate I Experimental Study of The Reaction Kinetics and Properties PDFDocument16 pages1 Solid State Polymerization of Poly Ethylene Terephthalate I Experimental Study of The Reaction Kinetics and Properties PDFSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- C4054 Uif PR 1010 FB 00001 2Document1 pageC4054 Uif PR 1010 FB 00001 2Siva KumarNo ratings yet

- Pet Polycondensation Side ReactionsDocument6 pagesPet Polycondensation Side ReactionsGeorge MarkasNo ratings yet

- New Doc 2018-02-27 - 1 PDFDocument1 pageNew Doc 2018-02-27 - 1 PDFSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- C4054 UIF PR 1010 DB 00001 0 General Process DescriptionDocument64 pagesC4054 UIF PR 1010 DB 00001 0 General Process DescriptionSiva Kumar100% (1)

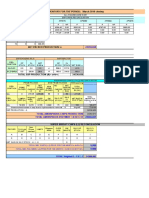

- INVENTORY FOR THE PERIOD: March 2016 ClosingDocument4 pagesINVENTORY FOR THE PERIOD: March 2016 ClosingSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- C4054 UIF PR 1010 DB 00006 0 OM V1 6 Schedule For Pre CommissioningDocument1 pageC4054 UIF PR 1010 DB 00006 0 OM V1 6 Schedule For Pre CommissioningSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- c4054 Uif PR 1015 DB 00001 0 Om V2a 05 CPC Sts PreparationDocument13 pagesc4054 Uif PR 1015 DB 00001 0 Om V2a 05 CPC Sts PreparationSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- C4054 UIF PR 1010 DB 00001 0 General Process DescriptionDocument64 pagesC4054 UIF PR 1010 DB 00001 0 General Process DescriptionSiva Kumar100% (1)

- DEG TankDocument2 pagesDEG TankSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- Cutting Defect FormatDocument1 pageCutting Defect FormatSiva KumarNo ratings yet

- BIRT Report Development in Maximo 7Document30 pagesBIRT Report Development in Maximo 7met-G Destiny Digital Communication EntertainmentNo ratings yet

- Improving Interface DesignDocument174 pagesImproving Interface Designayeh100% (2)

- C C++ Interview Questions AnswersDocument14 pagesC C++ Interview Questions Answersactiveguy_smalNo ratings yet

- Java Inheritance PDFDocument7 pagesJava Inheritance PDFMallikarjun AradhyaNo ratings yet

- GoldSim Volume2Document405 pagesGoldSim Volume2juba1200No ratings yet

- R-J3iC AuxAxis Setup Manual (System Installation Manual MARFCINST09051E REV.B)Document62 pagesR-J3iC AuxAxis Setup Manual (System Installation Manual MARFCINST09051E REV.B)trangovicNo ratings yet

- Subhadip Das ECE 2023Document3 pagesSubhadip Das ECE 2023Subhodip DasNo ratings yet

- Azure AD Mastery Training PlanDocument4 pagesAzure AD Mastery Training PlanArif Mohammed RangrezzNo ratings yet

- Microinstruction Format Concept of Horizontal and Vertical MicroprogrammingDocument16 pagesMicroinstruction Format Concept of Horizontal and Vertical MicroprogrammingDevilNo ratings yet

- Cybercrime in India: Trends and Challenges: December 2017Document11 pagesCybercrime in India: Trends and Challenges: December 2017Aleena Joseph KumbattuNo ratings yet

- 13 - Deploying Configuration Manager 2012 R2 Clients Using Group PolicyDocument9 pages13 - Deploying Configuration Manager 2012 R2 Clients Using Group PolicyAhmed BadieNo ratings yet

- 4595 BSBPMG512 Manage Project TimeDocument229 pages4595 BSBPMG512 Manage Project TimeKoshila Dodan0% (1)

- John The Ripper Usage Examples. Command Line.: Umask 077 Unshadow /etc/passwd /etc/shadow MypasswdDocument6 pagesJohn The Ripper Usage Examples. Command Line.: Umask 077 Unshadow /etc/passwd /etc/shadow MypasswdDidik WijayantoNo ratings yet

- HWC YWCi 9Document257 pagesHWC YWCi 9Stefan Mihai DodanNo ratings yet

- Saas Key PatterenDocument9 pagesSaas Key PatterenBELLA EVENo ratings yet

- AOLT-4000 OAM Manual PDFDocument546 pagesAOLT-4000 OAM Manual PDFBrenden CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- 3.2.5.12 Lab - Exploring The World of Cybersecurity ProfessionalsDocument3 pages3.2.5.12 Lab - Exploring The World of Cybersecurity ProfessionalsZeidan MohammadNo ratings yet

- CCNA Modul 11Document8 pagesCCNA Modul 11Hery Tjah KakoiNo ratings yet

- SIM7090G - Hardware Design - V1.02Document75 pagesSIM7090G - Hardware Design - V1.02Rodrigo VerniniNo ratings yet

- CSE 311L (Database Management System) LAB-Week 01 (Part A) : ObjectivesDocument2 pagesCSE 311L (Database Management System) LAB-Week 01 (Part A) : ObjectivesBayejid Bin Zahid 1611942642No ratings yet

- OS Midterm SolutionDocument4 pagesOS Midterm SolutionRofaelEmil100% (2)

- C 4: W C (D W) : Hapter EB Artography Esign Principles Applied TO THE EBDocument37 pagesC 4: W C (D W) : Hapter EB Artography Esign Principles Applied TO THE EBmasdiyana yusofNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6: Questions and AnswersDocument51 pagesChapter 6: Questions and Answersnnbphuong810% (2)

- ODI Loading MetaData and Data Into Planning and EssbaseDocument41 pagesODI Loading MetaData and Data Into Planning and Essbasesaikiran100% (1)

- CompTIA PenTest+ Domain 1 - Planning and ScopingDocument7 pagesCompTIA PenTest+ Domain 1 - Planning and Scopingcyb.saultNo ratings yet

- Fyjc It ObjectivesDocument21 pagesFyjc It ObjectivesMayur Kundar100% (1)

- System Software Conversion From Cisco IOS ToDocument39 pagesSystem Software Conversion From Cisco IOS ToYeffrey Garban MárquezNo ratings yet

- SAP Closing Cockpit Asdddddasd2132Document12 pagesSAP Closing Cockpit Asdddddasd2132JacekNo ratings yet

- MS Program ProspectusDocument27 pagesMS Program ProspectusweciansNo ratings yet

- Weapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingFrom EverandWeapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher's Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory SchoolingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (149)

- Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory SchoolingFrom EverandDumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory SchoolingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (496)

- How to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipFrom EverandHow to Talk to Anyone: Learn the Secrets of Good Communication and the Little Tricks for Big Success in RelationshipRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1135)

- Summary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Laws of Human Nature: by Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Summary: I'm Glad My Mom Died: by Jennette McCurdy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: I'm Glad My Mom Died: by Jennette McCurdy: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Summary: The 5AM Club: Own Your Morning. Elevate Your Life. by Robin Sharma: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The 5AM Club: Own Your Morning. Elevate Your Life. by Robin Sharma: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- The 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageFrom EverandThe 16 Undeniable Laws of Communication: Apply Them and Make the Most of Your MessageRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (73)

- Summary: Trading in the Zone: Trading in the Zone: Master the Market with Confidence, Discipline, and a Winning Attitude by Mark Douglas: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Trading in the Zone: Trading in the Zone: Master the Market with Confidence, Discipline, and a Winning Attitude by Mark Douglas: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (15)

- How to Improve English Speaking: How to Become a Confident and Fluent English SpeakerFrom EverandHow to Improve English Speaking: How to Become a Confident and Fluent English SpeakerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (56)

- Stoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionFrom EverandStoicism The Art of Happiness: How the Stoic Philosophy Works, Living a Good Life, Finding Calm and Managing Your Emotions in a Turbulent World. New VersionRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (51)

- Learn Spanish While SleepingFrom EverandLearn Spanish While SleepingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (20)

- Summary: Greenlights: by Matthew McConaughey: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: Greenlights: by Matthew McConaughey: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- The Story of the World, Vol. 1 AudiobookFrom EverandThe Story of the World, Vol. 1 AudiobookRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Why Smart People Hurt: A Guide for the Bright, the Sensitive, and the CreativeFrom EverandWhy Smart People Hurt: A Guide for the Bright, the Sensitive, and the CreativeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (54)

- Learn English: Must-Know American English Slang Words & Phrases (Extended Version)From EverandLearn English: Must-Know American English Slang Words & Phrases (Extended Version)Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (30)

- Summary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: It Didn't Start with You: How Inherited Family Trauma Shapes Who We Are and How to End the Cycle By Mark Wolynn: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Make It Stick by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel - Book Summary: The Science of Successful LearningFrom EverandMake It Stick by Peter C. Brown, Henry L. Roediger III, Mark A. McDaniel - Book Summary: The Science of Successful LearningRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (55)

- ChatGPT Money Machine 2024 - The Ultimate Chatbot Cheat Sheet to Go From Clueless Noob to Prompt Prodigy Fast! Complete AI Beginner’s Course to Catch the GPT Gold Rush Before It Leaves You BehindFrom EverandChatGPT Money Machine 2024 - The Ultimate Chatbot Cheat Sheet to Go From Clueless Noob to Prompt Prodigy Fast! Complete AI Beginner’s Course to Catch the GPT Gold Rush Before It Leaves You BehindNo ratings yet

- Learn Japanese - Level 1: Introduction to Japanese, Volume 1: Volume 1: Lessons 1-25From EverandLearn Japanese - Level 1: Introduction to Japanese, Volume 1: Volume 1: Lessons 1-25Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (17)

- Little Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School, and the Global Race to AchieveFrom EverandLittle Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School, and the Global Race to AchieveRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (25)

- Follow The Leader: A Collection Of The Best Lectures On LeadershipFrom EverandFollow The Leader: A Collection Of The Best Lectures On LeadershipRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (122)

- You Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsFrom EverandYou Are Not Special: And Other EncouragementsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity―and Why This Harms EverybodyFrom EverandCynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity―and Why This Harms EverybodyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (221)

- Summary: 12 Months to $1 Million: How to Pick a Winning Product, Build a Real Business, and Become a Seven-Figure Entrepreneur by Ryan Daniel Moran: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: 12 Months to $1 Million: How to Pick a Winning Product, Build a Real Business, and Become a Seven-Figure Entrepreneur by Ryan Daniel Moran: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Raising Human Beings: Creating a Collaborative Partnership with Your ChildFrom EverandRaising Human Beings: Creating a Collaborative Partnership with Your ChildRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (60)