Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vector 001 To 004

Uploaded by

Jin SiclonOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vector 001 To 004

Uploaded by

Jin SiclonCopyright:

Available Formats

INTRODUCTION

Introduction

History and background of vector control

At the end of the nineteenth century, it was discovered that certain species of insects, other arthropods and freshwater snails were responsible for the transmission of some important diseases. Since effective vaccines or drugs were not always available for the prevention or treatment of these diseases, control of transmission often had to rely mainly on control of the vector. Early control programmes included the screening of houses, the use of mosquito nets, the drainage or lling of swamps and other water bodies used by insects for breeding, and the application of oil or Paris green to breeding places. The discovery of the insecticide dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) in the 1940s was a major breakthrough in the control of vector-borne diseases. The insecticide was highly effective for killing indoor-resting mosquitos when it was sprayed on the walls of houses. Moreover, it was cheap to produce and remained active over a period of many months. DDT also appeared to be effective and economical in the control of other biting ies and midges and of infestations with eas, lice, bedbugs and triatomine bugs. In the 1950s and early 1960s, programmes were organized in many countries which attempted to control or eradicate the most important vector-borne diseases (malaria, Chagas disease and leishmaniasis) by the large-scale application of DDT. Because of their high costs, these programmes were generally planned for limited periods of time. The objective was to eradicate the diseases or to reduce transmission to such a low level that control could be maintained through the general health care facilities without the need for additional control measures. Initially these programmes were largely successful and in some countries it proved possible to interrupt or reduce the vector control activities. However, in most countries, success was short-lived; often the vectors developed resistance to the pesticides in use, creating a need for new, more expensive chemicals. Suspension of control programmes eventually led to a return to signicant levels of disease transmission. Permanent successes were mostly obtained where the environment was changed in such a way that the vector was prevented from breeding or resting.

Alternatives to the use of insecticides

Interest in alternatives to the use of insecticides, such as environmental management and biological control, has been revived because of increasing resistance to the commonly used insecticides among important vector species and because of concerns about the effects of DDT and certain other insecticides on the environment. Environmental management involves altering the breeding sites of the vectors, for instance by lling ponds and marshes on a permanent basis or by repeatedly removing vegetation from ponds and canals and cleaning premises. Biological control is the use of living organisms or their products to control vector and pest insects. The organisms used include viruses, bacteria, protozoa, fungi, plants, parasitic worms, predatory mosquitos and sh. The aim is generally to kill larvae without polluting the environment. Biological control often works best when used in combination with environmental management.

INTRODUCTION

Reorganization of vector control

In parallel with the investigation of alternative methods of control, attempts have been made in many countries to reorganize the delivery of services. Where possible, programmes for the control of vector-borne diseases have been decentralized and integrated with the basic and district health services. This is intended to improve the sustainability of control programmes while allowing substantial savings in nancial input and in staff costs. District and village health workers have assumed more responsibility. In the past decade, much emphasis has been given to adapting existing vector control techniques and developing new methods to enable general health personnel, communities and individuals to take action in defence of their own health. Priority has been given to the development of simple, safe, appropriate and inexpensive measures for vector control. Insecticide-treated nets and curtains have been developed for the control of mosquitos and sandies. Traps have been developed to control tsetse ies in Africa. House design and construction methods have been modied to control triatomine bugs in South America. Special water lters have been developed to eliminate the cyclops vectors of guinea worm from drinking-water. New irrigation techniques prevent mosquitos and snails from breeding but do not damage crops.

Vector control at community level

The particular vector control methods to be applied in a community will depend on the local situation and the preferences of the population. It is essential that communities are well informed about the options available, and that they participate actively in choosing and implementing vector control activities that are appropriate to their circumstances. Vector control methods suitable for community involvement should: be effective; be affordable; use equipment and materials that can be obtained locally; be simple to understand and apply; be acceptable and compatible with local customs, attitudes and beliefs; be safe to the user and the environment.

Methods that are suitable in one place are not necessarily so elsewhere, even if the characteristics of the disease and its vector are unchanged. Thus insecticide spraying of walls may be the preferred method for controlling malaria in one area while the use of insecticide-treated mosquito nets or environmental management may be more appropriate in another. The important differences between the various methods are related to the type and amount of involvement required from community members, village and district health workers, and vector control specialists. The choice of method will often depend on the availability of funds and trained personnel, the level of economic and social development of the community or area, and the level of development of local health services.

Selecting the appropriate control measures

In selecting appropriate control measures, it is generally possible to distinguish two types of situation requiring different solutions:

INTRODUCTION

nuisance caused by pests; diseases carried by bloodsucking insects and other vectors. In both cases, solutions can be found in the protection of individuals and the protection of communities. It is important to distinguish between measures offering adequate protection from disease and ones that are not sufcient on their own but are of value in conjunction with other measures. Before starting any vector control activity, it is important to ask two questions: result do you want to achieve: merely to protect yourself or your family What from biting pests and the diseases they carry, or to reduce disease in the community? Are health authorities already carrying out control measures and do you wantthe to provide the community or your family with additional protection from disease? Answering these questions is essential for the selection of the most appropriate control measures. For the correct diagnosis of a disease or identication of a vector or pest species, you may need to consult local health workers who should preferably also be involved in discussions about the need for and possibilities of control. People with experience in the control of agricultural pests may be of help. This manual provides background information that will help you to identify the vectors and diseases of importance in your community. Each chapter is divided into three sections. The rst section, on biology, should enable you to conrm the groups of arthropods to which the pests and vectors belong. It also provides background information indicating what to expect from specic control measures. The second section, on public health importance, briey reviews the diseases transmitted. For each disease, the place of vector control measures in strategies for disease control is described. Finally, practical information is given on a variety of control measures. The most detailed information concerns methods suitable for self-protection and community participation. Methods that have to be implemented by specially trained personnel are presented with minimum technical detail.

Self-protection

Self-protection measures are used to protect yourself, your family or a small group of people living or working together from insect pests or vectors of disease. These measures include personal protection, i.e., the prevention of contact between the human body and the disease vector, and environmental measures to prevent pests and vectors from entering, nding shelter in, or breeding in or around your house. These measures are usually simple and inexpensive, and can often be adopted without help from specialized health workers.

Community control

It is more difcult to protect a whole community from a vector-borne disease or major pest. The type of control may be the same as for the protection of an individual or a family, but is, of course, larger. A considerable effort is required in order to obtain the active participation of all members of the community.

INTRODUCTION

Before investing resources in community-wide control efforts, advice should be obtained from health workers on the type of measures most likely to be successful under local conditions. Many factors need to be taken into account: the vector species and its behaviour, the compatibility of control methods with the local culture, affordability in the long term, the need for expert advice, etc. In certain circumstances it is more cost-effective to improve the detection and treatment of sick people than to undertake vector control measures. On the other hand if the diagnosis of a disease is difcult or if adequate treatment is not available, vector control offers the only prospect of controlling the disease. After studying a particular situation, the community can use this manual to select the most suitable control measures; this selection should be based not only on the effectiveness of particular measures but also on their sustainability and affordability. It is also important to consider the type and amount of support local health services can provide on a sustainable basis.

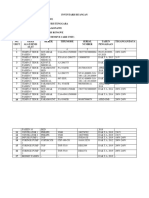

Input required from health services and communities for different types of control measures

Community input Health service input

low

<

high

Simple, inexpensive self-protection methods, requiring the active participation of the whole community. Examples: impregnated bednets, house improvement, prevention of breeding in and around houses. Technically simple methods to prevent breeding in the eld, requiring active participation of some members of the community under direct guidance of trained personnel. Examples: source reduction, larvivorous sh, larvicides. Methods requiring equipment, trained personnel, and nancial and technical involvement of the community. Example: insecticide spraying of house walls. Methods for the eradication of diseases or their vectors, requiring high investment for a limited period by the health service under the guidance of vector control experts. Examples: Onchocerciasis Control Programme in West Africa, malaria eradication programmes during the 1960s and 1970s.

low

Emergency control methods, requiring intense action by health services assisted by vector control experts. Examples: Ultra-low-volume spraying (fogging) with insecticides to control epidemics of dengue.

high

<

You might also like

- Worksheet#2-Maintaining Asepsis: Medical Asepsis Includes All Practices Intended To Confine A SpecificDocument4 pagesWorksheet#2-Maintaining Asepsis: Medical Asepsis Includes All Practices Intended To Confine A SpecificCj MayoyoNo ratings yet

- INFECTION CONTROL: PREVENTING CROSS-CONTAMINATIONDocument23 pagesINFECTION CONTROL: PREVENTING CROSS-CONTAMINATIONUdaya Sree67% (3)

- Online High School OM013: Honors Precalculus With TrigonometryDocument2 pagesOnline High School OM013: Honors Precalculus With TrigonometryJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Algae and Aquatic Biomass For A Sustainable Production of 2nd Generation BiofuelsDocument258 pagesAlgae and Aquatic Biomass For A Sustainable Production of 2nd Generation BiofuelsjcbobedaNo ratings yet

- Abdullahi Muhammad Musa PCC AssignmentDocument2 pagesAbdullahi Muhammad Musa PCC AssignmentAbdullahi Muhammad MusaNo ratings yet

- Dengue Prevention and Control in LebeDocument10 pagesDengue Prevention and Control in LebeRex AgustiloNo ratings yet

- VECTOR CONTROL METHODSDocument4 pagesVECTOR CONTROL METHODSmirabelle LovethNo ratings yet

- Cultural Methods of Pest, Primarily Insect, ControlDocument13 pagesCultural Methods of Pest, Primarily Insect, ControlrexNo ratings yet

- Dungi WHODocument9 pagesDungi WHObahaa mansourNo ratings yet

- Community Health and Community Health ProblemsDocument46 pagesCommunity Health and Community Health ProblemsJasmine GañganNo ratings yet

- 1Document2 pages1cloieNo ratings yet

- Econtent PDF IPM 55429Document8 pagesEcontent PDF IPM 55429AshilaNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 14 00124Document15 pagesIjerph 14 001242020210008No ratings yet

- Rev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz., 1995,14 (1), 105-122Document18 pagesRev. sci. tech. Off. int. Epiz., 1995,14 (1), 105-122RENZO ISAIAS SANTILLAN ZEVALLOSNo ratings yet

- Final Dengue Journal RHUDocument3 pagesFinal Dengue Journal RHUMAY JOY MARQUEZNo ratings yet

- Manual For IPC Program1Document79 pagesManual For IPC Program1SaadNo ratings yet

- The Ideal disinfectant-GPS-0620Document5 pagesThe Ideal disinfectant-GPS-0620sumiya mashadiNo ratings yet

- Pest ManagementDocument45 pagesPest ManagementRommel SacramentoNo ratings yet

- 14 Guy (Zoology) Biosecurity MeauDocument7 pages14 Guy (Zoology) Biosecurity MeauAyuba Adamu PampammiNo ratings yet

- Transcription Water Sanitation and Hygiene For The Prevention and Care of Neglected Tropical Diseases Module 1 ENDocument4 pagesTranscription Water Sanitation and Hygiene For The Prevention and Care of Neglected Tropical Diseases Module 1 ENCliff Daniel DIANZOLE MOUNKANANo ratings yet

- Chap 09Document13 pagesChap 09Yara AliNo ratings yet

- Part IDocument13 pagesPart IFatmawati rahimNo ratings yet

- Anti Microbial Pest Control ManualDocument19 pagesAnti Microbial Pest Control ManualZulfiqar AliNo ratings yet

- IPM Approach for Controlling Maize Lethal Necrosis in Sri LankaDocument8 pagesIPM Approach for Controlling Maize Lethal Necrosis in Sri LankaBAYODE MAYOWANo ratings yet

- PEST ControlDocument14 pagesPEST ControlDhiman Kanti Mridha100% (1)

- Hygiene Policy: PurposeDocument11 pagesHygiene Policy: PurposeNicky Patrick BaladhayNo ratings yet

- Ipm Program For Multi Family SocietyDocument6 pagesIpm Program For Multi Family SocietyShyam NayakNo ratings yet

- Chapter OneDocument10 pagesChapter OneSalome EtefiaNo ratings yet

- PHC3. Primary Health CareDocument71 pagesPHC3. Primary Health CareHumilyn NgayawonNo ratings yet

- Proper Excreta Disposal, Food Safety and Environmental HealthDocument15 pagesProper Excreta Disposal, Food Safety and Environmental HealthEden LacsonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Integrated Pest ManagementDocument5 pagesIntroduction To Integrated Pest ManagementWayli GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial - Stewardship - Program + MDRODocument15 pagesAntimicrobial - Stewardship - Program + MDROhebahamza0No ratings yet

- Infection Control Policies and ProceduresDocument9 pagesInfection Control Policies and ProceduresKelly J WilsonNo ratings yet

- Project ResearchDocument18 pagesProject ResearchhenjiegawiranNo ratings yet

- 188 Integrated Pest Management: Current and Future StrategiesDocument10 pages188 Integrated Pest Management: Current and Future StrategiesTaufik RizkiandiNo ratings yet

- 0902 Reversion Fo ResistranceDocument3 pages0902 Reversion Fo ResistranceVibhaMalikNo ratings yet

- Integrated Organic Pest ManagementDocument8 pagesIntegrated Organic Pest ManagementSchool Vegetable GardeningNo ratings yet

- Pest Control Protocol For Hospital and Related CentersDocument8 pagesPest Control Protocol For Hospital and Related CentersScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- WeedPestControlConventionalITO13 PDFDocument214 pagesWeedPestControlConventionalITO13 PDFbotelho.fernandes100% (2)

- Principles of Pest ControlDocument8 pagesPrinciples of Pest ControlrobotbusterNo ratings yet

- IjcbsDocument11 pagesIjcbsbuddhansamratNo ratings yet

- What Is Integrated Pest ManagementDocument2 pagesWhat Is Integrated Pest ManagementpeterlimttkNo ratings yet

- How To Implement IPMDocument4 pagesHow To Implement IPMZulfiqar AliNo ratings yet

- Vasquez - Bsn4a - Case Studies - Optional Credit (30 Points) - NCM 120 & Ic 7Document4 pagesVasquez - Bsn4a - Case Studies - Optional Credit (30 Points) - NCM 120 & Ic 7Mari Sheanne M. VasquezNo ratings yet

- Methods of Prevention and Control of InfectionDocument5 pagesMethods of Prevention and Control of InfectionDauda Muize AdewaleNo ratings yet

- IPM and GAP ExplainedDocument5 pagesIPM and GAP ExplainedRahadian Nandea JuliansyahNo ratings yet

- Insect Cntroll MethodsDocument3 pagesInsect Cntroll MethodsyogasanaNo ratings yet

- 04 Chapter6In-Tech PDFDocument18 pages04 Chapter6In-Tech PDFabrenzadael80No ratings yet

- Plant Disease Management StrategiesDocument14 pagesPlant Disease Management StrategiesKashish GuptaNo ratings yet

- Vector 357 To 384Document28 pagesVector 357 To 384Prasanta SanyalNo ratings yet

- Infection ControlDocument29 pagesInfection Controlkishoremanisha87No ratings yet

- Integrated Vector ManagementDocument34 pagesIntegrated Vector ManagementMayuri Vohra100% (1)

- Chapter 1. Integrated Pest ManagementDocument34 pagesChapter 1. Integrated Pest ManagementAna M. TorresNo ratings yet

- Jf-Ajtmh 2010Document7 pagesJf-Ajtmh 2010Jhibran FerralNo ratings yet

- Strengthen Community ActionsDocument5 pagesStrengthen Community ActionstermskipopNo ratings yet

- Topic: Pest Control With Whole Organism and Semiochemical ApproachesDocument6 pagesTopic: Pest Control With Whole Organism and Semiochemical Approachesarunimapradeep100% (1)

- Communicable Disease and PreventionDocument16 pagesCommunicable Disease and Preventionpempleo254No ratings yet

- MT Public Health Lab Activity Vector Control MethodsDocument2 pagesMT Public Health Lab Activity Vector Control Methodsirem corderoNo ratings yet

- Biological Control of Pest and DiseasesDocument5 pagesBiological Control of Pest and DiseasesMahabub hosenNo ratings yet

- Ecology and Integrated Pest ManagementDocument26 pagesEcology and Integrated Pest ManagementJ CamiloNo ratings yet

- Integrated Pest Management (IPM) : Sustainable Approaches to Pest ControlFrom EverandIntegrated Pest Management (IPM) : Sustainable Approaches to Pest ControlNo ratings yet

- 0confucian Education Model Position PaperDocument27 pages0confucian Education Model Position PaperjinlaksicNo ratings yet

- Climate Change Health FlyerDocument2 pagesClimate Change Health FlyerJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Climate Change Health FlyerDocument2 pagesClimate Change Health FlyerJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Xecutive Ummary: Work Sharing During The Great RecessionDocument4 pagesXecutive Ummary: Work Sharing During The Great RecessionJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Intro Self-Study EngDocument42 pagesIntro Self-Study EngJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- WHO Gender Climate Change and HealthDocument44 pagesWHO Gender Climate Change and HealthSarita MehraNo ratings yet

- WHO Gender Climate Change and HealthDocument44 pagesWHO Gender Climate Change and HealthSarita MehraNo ratings yet

- GuidelinesDocument9 pagesGuidelinesJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Social Protection Floor For A Fair and Inclusive GlobalizationDocument150 pagesSocial Protection Floor For A Fair and Inclusive GlobalizationSalam Salam Solidarity (fauzi ibrahim)No ratings yet

- Banking, Liquidity and Bank Runs in An Infinite-Horizon EconomyDocument43 pagesBanking, Liquidity and Bank Runs in An Infinite-Horizon EconomyJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Tendencias Mundiales Empleo - 2013 - OIT (Inglés)Document172 pagesTendencias Mundiales Empleo - 2013 - OIT (Inglés)David Velázquez SeiferheldNo ratings yet

- Essential Nutrition Actions: Improving Maternal, Newborn, Infant and Young Child Health and NutritionDocument116 pagesEssential Nutrition Actions: Improving Maternal, Newborn, Infant and Young Child Health and NutritionJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- CalcI TangentsRatesDocument10 pagesCalcI TangentsRatesJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- The Global Decline of The Labor ShareDocument47 pagesThe Global Decline of The Labor ShareJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Do Lottery Payments Induce Savings Behavior: Evidence From The LabDocument41 pagesDo Lottery Payments Induce Savings Behavior: Evidence From The LabJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- 06 Valid ArgumentsDocument31 pages06 Valid ArgumentsJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- The Wage Effects of Not-for-Profit and For-Profit Certifications: Better Data, Somewhat Different ResultsDocument41 pagesThe Wage Effects of Not-for-Profit and For-Profit Certifications: Better Data, Somewhat Different ResultsJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Disabled Beggars in Addis Ababa, EthiopiaDocument115 pagesDisabled Beggars in Addis Ababa, EthiopiaJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Deposit Insurance and Orderly Liquidation Without Commitment: Can We Sleep Well?Document35 pagesDeposit Insurance and Orderly Liquidation Without Commitment: Can We Sleep Well?Jin SiclonNo ratings yet

- The Philippines Employment Projections Model: Employment Targeting and ScenariosDocument77 pagesThe Philippines Employment Projections Model: Employment Targeting and ScenariosJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Towards The ILO Centenary: Realities, Renewal and Tripartite CommitmentDocument33 pagesTowards The ILO Centenary: Realities, Renewal and Tripartite CommitmentJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- International Perspectives On Women and Work in Hotels, Catering and TourismDocument75 pagesInternational Perspectives On Women and Work in Hotels, Catering and TourismJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Globalization, Employment and Gender in The Open Economy of Sri LankaDocument56 pagesGlobalization, Employment and Gender in The Open Economy of Sri LankaJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Promoting Employment Intensive Growth in Sri Lanka: An Assessment of Key SectorsDocument94 pagesPromoting Employment Intensive Growth in Sri Lanka: An Assessment of Key SectorsJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Labour Inspection Sanctions: Law and Practice of National Labour Inspection SystemsDocument52 pagesLabour Inspection Sanctions: Law and Practice of National Labour Inspection SystemsJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- RA-10535 Act of Philippine Standard TimeDocument3 pagesRA-10535 Act of Philippine Standard TimeEli Benjamin Nava TaclinoNo ratings yet

- Cities With Jobs: Confronting The Employment Challenge, Research ReportDocument139 pagesCities With Jobs: Confronting The Employment Challenge, Research ReportJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Towards More Inclusive Employment Policy Making: Process and Role of Stakeholders in Indonesia, Nicaragua, Moldova and UgandaDocument185 pagesTowards More Inclusive Employment Policy Making: Process and Role of Stakeholders in Indonesia, Nicaragua, Moldova and UgandaJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- Local Governance and The Informal Economy: Experiences in Promoting Decent Work in The PhilippinesDocument105 pagesLocal Governance and The Informal Economy: Experiences in Promoting Decent Work in The PhilippinesJin SiclonNo ratings yet

- CattabrigaF45 90 120Document21 pagesCattabrigaF45 90 120Fernando William Rivera CuadrosNo ratings yet

- Housekeeping in The Dental OfficeDocument45 pagesHousekeeping in The Dental OfficeJhaynerzz Padilla AcostaNo ratings yet

- KT 470Document4 pagesKT 470Fabian PzvNo ratings yet

- Network Marketing BusinessesDocument1 pageNetwork Marketing BusinessessukhberNo ratings yet

- School Form 2 Daily Attendance Report of Learners For Senior High School (SF2-SHS)Document2 pagesSchool Form 2 Daily Attendance Report of Learners For Senior High School (SF2-SHS)Charly Mint Atamosa IsraelNo ratings yet

- Hygro-Thermometer Pen: User's GuideDocument4 pagesHygro-Thermometer Pen: User's GuideTedosNo ratings yet

- Leave Policy For EmployeesDocument9 pagesLeave Policy For EmployeesMEGHA PALANDENo ratings yet

- Continuity of Education in the New NormalDocument2 pagesContinuity of Education in the New NormalMon Agulto LomedaNo ratings yet

- Icu (Intensive Care Unit)Document2 pagesIcu (Intensive Care Unit)IrfanNo ratings yet

- Birth Control GuideDocument4 pagesBirth Control GuideNessaNo ratings yet

- Pressure VesselDocument114 pagesPressure Vesseldanemsal100% (3)

- CSFDocument5 pagesCSFjalan_zNo ratings yet

- Specification For Firewater Pump Package S 721v2020 08Document90 pagesSpecification For Firewater Pump Package S 721v2020 08Serge RINAUDONo ratings yet

- Cancer Treatment HomeopathyDocument121 pagesCancer Treatment Homeopathykshahulhameed100% (1)

- Analiza PESTDocument16 pagesAnaliza PESTIoana Ciobanu100% (1)

- 3 Novec™ 1230 Fire Protection Fluid Data SheetDocument4 pages3 Novec™ 1230 Fire Protection Fluid Data SheetL ONo ratings yet

- hc2019 Re Use Recycle To Reduce CarbonDocument68 pageshc2019 Re Use Recycle To Reduce CarbonFatemeh DavariNo ratings yet

- Camille Pissarro Paintings For ReproductionDocument827 pagesCamille Pissarro Paintings For ReproductionPaintingZ100% (1)

- Topic 3. Ecosystems (4 Marks) : Q. No. Option I Option II Option III Option IV Answer KeyDocument2 pagesTopic 3. Ecosystems (4 Marks) : Q. No. Option I Option II Option III Option IV Answer KeysakshiNo ratings yet

- Summary of Nursing TheoriesDocument1 pageSummary of Nursing TheoriesNica Nario Asuncion100% (1)

- 3rd Quiz Review On Prof EdDocument13 pages3rd Quiz Review On Prof EdJohn Patrick EnrileNo ratings yet

- MEP Final Corrected 2Document17 pagesMEP Final Corrected 2Prakhyati RautNo ratings yet

- Molykote: 111 CompoundDocument2 pagesMolykote: 111 CompoundEcosuministros ColombiaNo ratings yet

- 3 Reliability and ValidityDocument16 pages3 Reliability and ValiditySyawal Anizam100% (1)

- Department of Labor: ls-200Document2 pagesDepartment of Labor: ls-200USA_DepartmentOfLaborNo ratings yet

- Incident Report TemplateDocument3 pagesIncident Report Templateapi-412577219No ratings yet

- Drinking Water Booklet - 05-14-2007Document152 pagesDrinking Water Booklet - 05-14-2007Minos_CoNo ratings yet

- The Practice of Yoga and Its Philosophy FinalDocument23 pagesThe Practice of Yoga and Its Philosophy Finalshwets91No ratings yet