BASIC THEORY OF DIESEL ENGINE

By Er.Laxman Singh Sankhla B.E.Mech., Chartered Engineer Jodhpur, India Mail ID: laxman9992001@yahoo.co.in

BASIC THEORY OF DIESEL ENGINE. In a diesel engine, ignition of the fuel is accomplished by the heat of compression alone. To support combustion, air is required. Approximately 14 pounds of air is required for the combustion of 1 pound of fuel oil. However, to insure complete combustion of the fuel, an excess amount of air is always supplied to the cylinders. The ratio of the amount of air supplied to the quantity of fuel injected during each power stroke is called the air-fuel ratio and is an important factor in the operation of any internal-combustion engine. When the engine is operating at light loads there is a, large excess of air present, and even when the engine is overloaded, there is an excess of air over the minimum required for complete combustion. The injected fuel must be divided into small particles, usually by mechanical atomization, as it is sprayed or injected into the combustion chamber. It is imperative that each of the small particles be completely surrounded by sufficient air to effect complete combustion of the fuel. To accomplish this, the air in the cylinder must be in motion with good fuel atomization, combined with penetration and distribution.

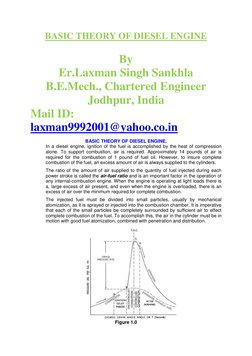

Figure 1.0

�Figure 1.0 is a reproduction of pressure-time diagram of a diesel engine. The lower curvy part of which is a dotted line, is the curve of compression and expansion when no fuel is injected. At A the injection valve opens, fuel enters the combustion chamber and ignition occurs at B. The pressure from A to B should fall slightly below the compression curve without fuel due to absorption of heat by the fuel from the air. The period from A to B is the ignition delay. From B the pressure rises rapidly until it reaches a maximum at C. This maximum, in some instances, may occur at top dead center. At D the injection valve closes, the fuel is cut off, but burning of the fuel continues to some undetermined point along the expansion stroke. The height of the diagram from B to C is called the firing pressure rise and the slope of the curve between these two points is the rate at which the fuel is burned.

Figure 2.0 Theoretically, in a diesel cycle the combustion takes place at constant volume rather than at constant pressure as we can see in Figure 2.0. Most diesels are also fourstroke engines but there are two stroke diesels in operation. The first, or suction stroke (e a) draws air, but no fuel, into the combustion chamber through an intake valve. On the second, or compression stroke (a b) the air is compressed to a small fraction of its former volume and is heated to approximately 440 C (approximately 820 F) by this compression. At the end of the compression stroke, vaporized fuel is injected into the combustion chamber (Q1) and burns instantly because of the high temperature of the air in the chamber. Some diesels have auxiliary electrical ignition systems to ignite the fuel when the engine starts and until it warms up. This combustion drives the piston back on the third, or power stroke (c d a) of the cycle. The fourth stroke, (a e) is an exhaust stroke. The key properties and some useful information about diesel fuel is attached to the end of this module. Diesel fuel is mainly a mixture of hydrocarbons in liquid form. A hydrocarbon is a chemical compound composed of hydrogen and carbon. When hydrogen combines with oxygen the following reaction takes place: 2H2 + O2 = 2 H2O Carbon burns with Oxygen in two proportions. First it burns with available oxygen and forms carbon monoxide. If plenty of oxygen is available complete combustion takes according to following equations:

�2C + O2 = 2CO Carbon monoxide, CO, is poisonous gas. It readily combines with oxygen to form carbon dioxide CO2 according to equation 2CO + O2 = 2CO2 If sufficient oxygen is available carbon readily combines with oxygen to form carbon dioxide CO2 according to equation C +O2 = CO2 Another combustible but undesirable element found in fuels in small amount is sulfur. Sulfur, S, burns with oxygen to form sulfur dioxide SO2 as follows: S +O2 = SO2 Sulfur dioxide is a corrosive gas in the presence of water. It is responsible for the corrosion found inside the exhaust pipes. The efficiency of the diesel engine is inherently greater than that of any Otto-cycle engine and in actual engines today is slightly more than 40 percent. Diesel engines are, in general, slow-speed engines with crankshaft speeds of 100 to 750 revolutions per minute (rpm). Some types of diesel, however, have speeds up to 2000 rpm. Because diesels use compression ratios of 14 or more to 1, they are generally more heavily built but this disadvantage is counterbalanced by their greater efficiency and the fact that they can be operated on less expensive fuel oils.